Substituted amphetamine

Substituted amphetamines are a class of compounds based upon the amphetamine structure;[1] it includes all derivative compounds which are formed by replacing, or substituting, one or more hydrogen atoms in the amphetamine core structure with substituents.[1][2][3][4] The compounds in this class span a variety of pharmacological subclasses, including stimulants, empathogens, and hallucinogens, among others.[2] Examples of substituted amphetamines are amphetamine (itself),[1][2] methamphetamine,[1] ephedrine,[1] cathinone,[1] phentermine,[1] mephentermine,[1] bupropion,[1] methoxyphenamine,[1] selegiline,[1] amfepramone,[1] pyrovalerone,[1] MDMA (ecstasy), and DOM (STP).

| Substituted amphetamine | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

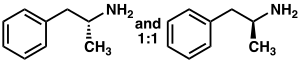

Racemic amphetamine skeleton | |

| Class identifiers | |

| Chemical class | Substituted derivatives of amphetamine |

| In Wikidata | |

|  |

| L-amphetamine | D-amphetamine |

Some of amphetamine's substituted derivatives occur in nature, for example in the leaves of Ephedra and khat plants which have been used by humans for more than 1000 years for their pharmacological effects.[1] Amphetamine was first produced at the end of the 19th century. By the 1930s, amphetamine and some of its derivative compounds found use as decongestants in the symptomatic treatment of colds and also occasionally as psychoactive agents. Their effects on the central nervous system are diverse, but can be summarized by three overlapping types of activity: psychoanaleptic, hallucinogenic and empathogenic. Various substituted amphetamines may cause these actions either separately or in combination.

Partial list of substituted amphetamines

| Generic or Trivial Name | Chemical Name | # of Subs |

|---|---|---|

| Amphetamine | α-Methyl-phenethylamine | 0 |

| Methamphetamine | N-Methylamphetamine | 1 |

| Ethylamphetamine | N-Ethylamphetamine | 1 |

| Propylamphetamine | N-Propylamphetamine | 1 |

| Isopropylamphetamine | N-iso-Propylamphetamine | 1 |

| Phentermine | α-Methylamphetamine | 1 |

| Phenylpropanolamine (PPA) | β-Hydroxyamphetamine, (1R,2S)- | 1 |

| Cathine | β-Hydroxyamphetamine, (1S,2S)- | 1 |

| Cathinone | β-Ketoamphetamine | 1 |

| Ortetamine | 2-Methylamphetamine | 1 |

| 2-Fluoroamphetamine (2-FA) | 2-Fluoroamphetamine | 1 |

| 3-Methylamphetamine (3-MA) | 3-Methylamphetamine | 1 |

| 2-Phenyl-3-aminobutane | 2-Phenyl-3-aminobutane | 1 |

| 3-Fluoroamphetamine (3-FA) | 3-Fluoroamphetamine | 1 |

| Norfenfluramine | 3-Trifluoromethylamphetamine | 1 |

| 4-Methylamphetamine (4-MA) | 4-Methylamphetamine | 1 |

| para-Methoxyamphetamine (PMA) | 4-Methoxyamphetamine | 1 |

| para-Ethoxyamphetamine | 4-Ethoxyamphetamine | 1 |

| 4-Methylthioamphetamine (4-MTA) | 4-Methylthioamphetamine | 1 |

| Norpholedrine (α-Me-TRA) | 4-Hydroxyamphetamine | 1 |

| para-Bromoamphetamine (PBA, 4-BA) | 4-Bromoamphetamine | 1 |

| para-Chloroamphetamine (PCA, 4-CA) | 4-Chloroamphetamine | 1 |

| para-Fluoroamphetamine (PFA, 4-FA, 4-FMP) | 4-Fluoroamphetamine | 1 |

| para-Iodoamphetamine (PIA, 4-IA) | 4-Iodoamphetamine | 1 |

| Clobenzorex | N-(2-chlorobenzyl)-1-phenylpropan-2-amine | 1 |

| Dimethylamphetamine | N,N-Dimethylamphetamine | 2 |

| Benzphetamine | N-Benzyl-N-methylamphetamine | 2 |

| D-Deprenyl | N-Methyl-N-propargylamphetamine, (S)- | 2 |

| Selegiline | N-Methyl-N-propargylamphetamine, (R)- | 2 |

| Mephentermine | N-Methyl-α-methylamphetamine | 2 |

| Phenpentermine | α,β-Dimethylamphetamine | 2 |

| Ephedrine | β-Hydroxy-N-methylamphetamine, (1R,2S)- | 2 |

| Pseudoephedrine (PSE) | β-Hydroxy-N-methylamphetamine, (1S,2S)- | 2 |

| Methcathinone | β-Keto-N-methylamphetamine | 2 |

| Ethcathinone | β-Keto-N-ethylamphetamine | 2 |

| Clortermine | 2-Chloro-α-methylamphetamine | 2 |

| Methoxymethylamphetamine (MMA) | 3-Methoxy-4-methylamphetamine | 2 |

| Fenfluramine | 3-Trifluoromethyl-N-ethylamphetamine | 2 |

| Dexfenfluramine | 3-Trifluoromethyl-N-ethylamphetamine, (S)- | 2 |

| 4-Methylmethamphetamine (4-MMA) | 4-Methyl-N-methylamphetamine | 2 |

| para-Methoxymethamphetamine (PMMA) | 4-Methoxy-N-methylamphetamine | 2 |

| para-Methoxyethylamphetamine (PMEA) | 4-Methoxy-N-ethylamphetamine | 2 |

| Pholedrine | 4-Hydroxy-N-methylamphetamine | 2 |

| Chlorphentermine | 4-Chloro-α-methylamphetamine | 2 |

| para-Fluoromethamphetamine (PFMA, 4-FMA) | 4-Fluoro-N-methylamphetamine | 2 |

| Xylopropamine | 3,4-Dimethylamphetamine | 2 |

| α-Methyldopamine (α-Me-DA) | 3,4-Dihydroxyamphetamine | 2 |

| 3,4-Methylenedioxyamphetamine (MDA) | 3,4-Methylenedioxyamphetamine | 2 |

| Dimethoxyamphetamine (DMA) | X,X-Dimethoxyamphetamine | 2 |

| 6-APB | 6-(2-aminopropyl)benzofuran | 2 |

| Nordefrin (α-Me-NE) | β,3,4-Trihydroxyamphetamine, (R)- | 3 |

| Oxilofrine | β,4-Dihydroxy-N-methylamphetamine | 3 |

| Aleph | 2,5-dimethoxy-4-methylthioamphetamine | 3 |

| Dimethoxybromoamphetamine (DOB) | 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-bromoamphetamine | 3 |

| Dimethoxychloroamphetamine (DOC) | 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-chloroamphetamine | 3 |

| Dimethoxyfluoroethylamphetamine (DOEF) | 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-fluoroethylamphetamine | 3 |

| Dimethoxyethylamphetamine (DOET) | 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-ethylamphetamine | 3 |

| Dimethoxyfluoroamphetamine (DOF) | 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-fluoroamphetamine | 3 |

| Dimethoxyiodoamphetamine (DOI) | 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine | 3 |

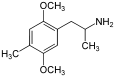

| Dimethoxymethylamphetamine (DOM) | 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine | 3 |

| Dimethoxynitroamphetamine (DON) | 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-nitroamphetamine | 3 |

| Dimethoxypropylamphetamine (DOPR) | 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-propylamphetamine | 3 |

| Dimethoxytrifluoromethylamphetamine (DOTFM) | 2,5-Dimethoxy-4-trifluoromethylamphetamine | 3 |

| Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) | 3,4-Methylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine | 3 |

| Methylenedioxyethylamphetamine (MDEA) | 3,4-Methylenedioxy-N-ethylamphetamine | 3 |

| Methylenedioxyhydroxyamphetamine (MDOH) | 3,4-Methylenedioxy-N-hydroxyamphetamine | 3 |

| 2-Methyl-MDA | 3,4-Methylenedioxy-2-methylamphetamine | 3 |

| 5-Methyl-MDA | 4,5-Methylenedioxy-3-methylamphetamine | 3 |

| Methoxymethylenedioxyamphetamine (MMDA) | 3-Methoxy-4,5-methylenedioxyamphetamine | 3 |

| Trimethoxyamphetamine (TMA) | X,X,X-Trimethoxyamphetamine | 3 |

| Dimethylcathinone | β-Keto-N,N-dimethylamphetamine | 3 |

| Diethylcathinone | β-Keto-N,N-diethylamphetamine | 3 |

| Bupropion | β-Keto-3-chloro-N-tert-butylamphetamine | 3 |

| Mephedrone (4-MMC) | β-Keto-4-methyl-N-methylamphetamine | 3 |

| Methedrone (PMMC) | β-Keto-4-methoxy-N-methylamphetamine | 3 |

| Brephedrone (4-BMC) | β-Keto-4-bromo-N-methylamphetamine | 3 |

| Flephedrone (4-FMC) | β-Keto-4-fluoro-N-methylamphetamine | 3 |

Prodrugs of amphetamine/methamphetamine

A variety of prodrugs of amphetamine and/or methamphetamine exist, and include amfecloral, amphetaminil, benzphetamine, clobenzorex, D-deprenyl, dimethylamphetamine, ethylamphetamine, fencamine, fenethylline, fenproporex, furfenorex, lisdexamfetamine, mefenorex, prenylamine, and selegiline.[5]

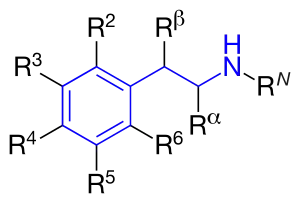

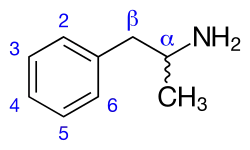

Structure

Amphetamines are a subgroup of the substituted phenethylamine class of compounds. Substitution of hydrogen atoms results in a large class of compounds. Typical reaction is substitution by methyl and sometimes ethyl groups at the amine and phenyl sites:[7][8][9]

| Substance | Substituents | Structure | Sources | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | α | β | phenyl group | ||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||||

| Phenethylamine | |||||||||

| Amphetamine (α-methylphenylethylamine) | -CH3 | [6] | |||||||

| Methamphetamine (N-methylamphetamine) | -CH3 | -CH3 | [6] | ||||||

| Phentermine (α-methylamphetamine) | -(CH3)2 | [6] | |||||||

| Ephedrine | -CH3 | -CH3 | -OH | [6] | |||||

| Pseudoephedrine | -CH3 | -CH3 | -OH | [6] | |||||

| Cathinone | -CH3 | =O | [6] | ||||||

| Methcathinone (ephedrone) | -CH3 | -CH3 | =O | [6] | |||||

| MDA (3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine) | -CH3 | -O-CH2-O- | [6] | ||||||

| MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine) | -CH3 | -CH3 | -O-CH2-O- | [6] | |||||

| MDEA (3,4-methylenedioxy-N-ethylamphetamine) | -CH2-CH3 | -CH3 | -O-CH2-O- | [6] | |||||

| EDMA (3,4-ethylenedioxy-N-methylamphetamine) | -CH3 | -CH3 | -O-CH2-CH2-O- | ||||||

| MBDB (N-methyl-1,3-benzodioxolylbutanamine) | -CH3 | -CH2-CH3 | -O-CH2-O- | ||||||

| PMA (para-methoxyamphetamine) | -CH3 | -O-CH3 | |||||||

| PMMA (para-methoxymethamphetamine) | -CH3 | -CH3 | -O-CH3 | ||||||

| 4-MTA (4-methylthioamphetamine) | -CH3 | -S-CH3 | |||||||

| 3,4-DMA (3,4-dimethoxyamphetamine) | -CH3 | -O-CH3 | -O-CH3 | ||||||

| 3,4,5-Trimethoxyamphetamine (α-methylmescaline) | -CH3 | -O-CH3 | -O-CH3 | -O-CH3 | |||||

| DOM (2,5-dimethoxy-4-methylamphetamine) | -CH3 | -O-CH3 | -CH3 | -O-CH3 |  |

||||

| DOB (2,5-dimethoxy-4-bromoamphetamine) | -CH3 | -O-CH3 | -Br | -O-CH3 |  |

||||

History

Ephedra was used 5000 years ago in China as a medicinal plant; its active ingredients are alkaloids ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, norephedrine (phenylpropanolamine) and norpseudoephedrine (cathine). Natives of Yemen and Ethiopia have a long tradition of chewing khat leaves to achieve a stimulating effect. The active substances of khat are cathinone and, to a lesser extent, cathine.[10]

Amphetamine was first synthesized in 1887 by Romanian chemist Lazăr Edeleanu, although its pharmacological effects remained unknown until the 1930s.[11] MDMA was produced in 1912 (according to other sources in 1914[12]) as an intermediate product. However, this synthesis also went largely unnoticed.[13] In the 1920s, both methamphetamine and the dextrorotatory optical isomer of amphetamine, dextroamphetamine, were synthesized. This synthesis was a by-product of a search for ephedrine, a bronchodilator used to treat asthma extracted exclusively from natural sources. Over-the-counter use of substituted amphetamines was initiated in the early 1930s by the pharmaceutical company Smith, Kline & French (now part of GlaxoSmithKline), as a medicine (Benzedrine) for colds and nasal congestion. Subsequently, amphetamine was used in the treatment of narcolepsy, obesity, hay fever, orthostatic hypotension, epilepsy, Parkinson's disease, alcoholism and migraine.[11][14] The "reinforcing" effects of substituted amphetamines were quickly discovered, and the misuse of substituted amphetamines had been noted as far back as 1936.[14]

During World War II, amphetamines were used by the German military to keep their tank crews awake for long periods, and treat depression. It was noticed that extended rest was required after such artificially induced activity.[11] The widespread use of substituted amphetamines began in postwar Japan and quickly spread to other countries. Modified "designer amphetamines" gained popularity since the 1960s, such as MDA and PMA.[14] In 1970, the United States adopted "the Controlled Substances Act" that limited non-medical use of substituted amphetamines.[14] Street use of PMA was noted in 1972.[15] MDMA emerged as a substitute to MDA in the early 1970s.[16] American chemist Alexander Shulgin first synthesized the drug in 1976 and through him the drug was briefly introduced into psychotherapy.[17] Recreational use grew and in 1985 MDMA was banned by the US authorities in an emergency scheduling initiated by the Drug Enforcement Administration.[18]

Since the mid-1990s, MDMA has become a popular entactogenic drug among the youth and quite often non-MDMA substances were sold as ecstasy.[19] Ongoing trials are investigating its efficacy as an adjunct to psychotherapy in the management of treatment-resistant post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[20]

Legal status

| Agents | Legal status by 2009.[21][22][23][24] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances of 1971[25] | US | Russia | Australia | |

| Amphetamine (racemic) | Schedule II | Schedule II | Schedule II | Schedule 8 |

| Dextroamphetamine (D-amphetamine) | Schedule II | Schedule II | Schedule I | Schedule 8 |

| Levoamphetamine (L-amphetamine) | Schedule II | Schedule II | Schedule III | Schedule 8 |

| Methamphetamine | Schedule II | Schedule II | Schedule I | Schedule 8 |

| Cathinone Methcathinone | Schedule I | Schedule I | Schedule I | Schedule 9 |

| MDA, MDMA, MDEA | Schedule I | Schedule I | Schedule I | Schedule 9 |

| PMA | Schedule I | Schedule I | Schedule I | Schedule 9 |

| DOB, DOM, 3,4,5-TMA | Schedule I | Schedule I | Schedule I | Schedule 9 |

See also

- Substituted phenethylamines

- Substituted methylenedioxyphenethylamines

- Substituted cathinones

- Substituted phenylmorpholines

- 2Cs, DOx, 25-NB

- Substituted tryptamines

- Substituted α-alkyltryptamines

- D-Deprenyl, MAO-B inhibitor prodrug that metabolizes into both D-amphetamine and D-methamphetamine

- Amphetaminil, brand name Aponeuron a largely-market-withdrawn (due to abuse liability) amphetamine

References

- Hagel JM, Krizevski R, Marsolais F, Lewinsohn E, Facchini PJ (2012). "Biosynthesis of amphetamine analogs in plants". Trends Plant Sci. 17 (7): 404–412. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2012.03.004. PMID 22502775.

Substituted amphetamines, which are also called phenylpropylamino alkaloids, are a diverse group of nitrogen-containing compounds that feature a phenethylamine backbone with a methyl group at the α-position relative to the nitrogen (Figure 1). Countless variation in functional group substitutions has yielded a collection of synthetic drugs with diverse pharmacological properties as stimulants, empathogens and hallucinogens [3]. ... Beyond (1R,2S)-ephedrine and (1S,2S)-pseudoephedrine, myriad other substituted amphetamines have important pharmaceutical applications. The stereochemistry at the α-carbon is often a key determinant of pharmacological activity, with (S)-enantiomers being more potent. For example, (S)-amphetamine, commonly known as d-amphetamine or dextroamphetamine, displays five times greater psychostimulant activity compared with its (R)-isomer [78]. Most such molecules are produced exclusively through chemical syntheses and many are prescribed widely in modern medicine. For example, (S)-amphetamine (Figure 4b), a key ingredient in Adderall and Dexedrine, is used to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [79]. ...

[Figure 4](b) Examples of synthetic, pharmaceutically important substituted amphetamines. - Glennon RA (2013). "Phenylisopropylamine stimulants: amphetamine-related agents". In Lemke TL, Williams DA, Roche VF, Zito W (eds.). Foye's principles of medicinal chemistry (7th ed.). Philadelphia, USA: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 646–648. ISBN 9781609133450.

The simplest unsubstituted phenylisopropylamine, 1-phenyl-2-aminopropane, or amphetamine, serves as a common structural template for hallucinogens and psychostimulants. Amphetamine produces central stimulant, anorectic, and sympathomimetic actions, and it is the prototype member of this class (39).

- Lillsunde P, Korte T (March 1991). "Determination of ring- and N-substituted amphetamines as heptafluorobutyryl derivatives". Forensic Sci. Int. 49 (2): 205–213. doi:10.1016/0379-0738(91)90081-s. PMID 1855720.

- Custodio, Raly James Perez; Botanas, Chrislean Jun; Yoon, Seong Shoon; Peña, June Bryan de la; Peña, Irene Joy dela; Kim, Mikyung; Woo, Taeseon; Seo, Joung-Wook; Jang, Choon-Gon; Kwon, Yong Ho; Kim, Nam Yong (1 November 2017). "Evaluation of the Abuse Potential of Novel Amphetamine Derivatives with Modifications on the Amine (NBNA) and Phenyl (EDA, PMEA, 2-APN) Sites". Biomolecules & Therapeutics. 25 (6): 578–585. doi:10.4062/biomolther.2017.141. ISSN 2005-4483. PMC 5685426. PMID 29081089.

- Reinhard Dettmeyer; Marcel A. Verhoff; Harald F. Schütz (9 October 2013). Forensic Medicine: Fundamentals and Perspectives. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 519–. ISBN 978-3-642-38818-7.

- Barceloux DG (February 2012). "Chapter 1: Amphetamine and Methamphetamine". Medical Toxicology of Drug Abuse: Synthesized Chemicals and Psychoactive Plants (First ed.). John Wiley & Sons. p. 5. ISBN 9781118106051. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- Goldfrank, pp. 1125–1127

- Glennon, pp. 184–187

- Schatzberg, p.843

- Paul M Dewick (2002). Medicinal Natural Products. A Biosynthetic Approach. Second Edition. Wiley. pp. 383–384. ISBN 978-0-471-49640-3.

- Snow, p. 1

- A. Richard Green, et al. (2003). "The Pharmacology and Clinical Pharmacology of 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, Ecstasy)". Pharmacological Reviews. 55 (3): 463–508. doi:10.1124/pr.55.3.3. PMID 12869661. S2CID 1786307.

- Goldfrank, p. 1125

- Goldfrank, p. 1119

- Liang Han Ling, et al. (2001). "Poisoning with the recreational drug paramethoxyamphetamine ("death" )". The Medical Journal of Australia. 174 (9): 453–5. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143372.x. hdl:2440/14508. PMID 11386590. S2CID 37596142. Archived from the original on 26 November 2009.

- Foderaro, Lisa W. (11 December 1988). "Psychedelic Drug Called Ecstasy Gains Popularity in Manhattan Nightclubs". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Archived from the original on 17 November 2015. Retrieved 27 August 2015.

- Benzenhöfer, Udo; Passie, Torsten (9 July 2010). "Rediscovering MDMA (ecstasy): the role of the American chemist Alexander T. Shulgin". Addiction. 105 (8): 1355–1361. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02948.x. PMID 20653618.

- Snow, p. 71

- Goldfrank, p. 1121

- Mithoefer M., et al. (2011). "The safety and efficacy of ±3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-assisted psychotherapy in subjects with chronic, treatment-resistant posttraumatic stress disorder: the first randomized controlled pilot study". Journal of Psychopharmacology. 25 (4): 439–52. doi:10.1177/0269881110378371. PMC 3122379. PMID 20643699.

- "List of psychotropic substances under international control" (PDF). International Narcotics Control Board. August 2003. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) May 2010 Edition Archived 24 December 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "DEA Drug Scheduling". U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. Archived from the original on 10 February 2011. Retrieved 17 November 2009.

- "Resolution of RF Government of 30 June 1998 N 681 "On approval of list of drugs psychotropic substances and their precursors subject to control in the Russian Federation"". garant.ru (in Russian). Archived from the original on 29 January 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- "The Standard for the Uniform Scheduling of Medicines and Poisons (SUSMP)". Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Archived from the original on 27 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- "Convention on Psychotropic Substances, 1971" (PDF). United Nations. Archived from the original on 25 November 2010.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

Bibliography

- Ghodse, Hamid (2002). Drugs and Addictive Behaviour. A Guide to Treatment. 3rd Edition. Cambridge University Press. p. 501. ISBN 978-0-511-05844-8.

- Glennon, Richard A. (2008). "Neurobiology of Hallucinogens". The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of substance abuse treatment. American Psychiatric Publishing. ISBN 978-1-58562-276-4.

- Goldfrank, Lewis R. & Flomenbaum, Neal (2006). Goldfrank's Toxicologic Emergencies, 8th Edition. McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-147914-1.

- Katzung, Bertram G. (2009). Basic & clinical pharmacology. 11th edition. McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0-07-160405-5.

- Ledgard, Jared (2007). A Laboratory History of Narcotics. Volume 1. Amphetamines and Derivatives. Jared Ledgard. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-615-15694-1.

- Schatzberg, Alan F. & Nemeroff, Charles B. (2009). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychopharmacology. The American Psychiatric Publishing. ISBN 978-1-58562-309-9.

- Snow, Otto (2002). Amphetamine syntheses. Thoth Press. ISBN 978-0-9663128-3-6.

- Veselovskaya NV, Kovalenko AE (2000). Drugs. Properties, effects, pharmacokinetics, metabolism. MA: Triada-X. ISBN 978-5-94497-029-9.

External links

Media related to Substituted amphetamines at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Substituted amphetamines at Wikimedia Commons