Himno Nacional Mexicano

| English: Mexican National Anthem | |

|---|---|

| |

National anthem of | |

| Also known as | "Mexicanos, al grito de guerra" (English: "Mexicans, at the cry of war") |

| Lyrics | Francisco González Bocanegra, 1853 |

| Music | Jaime Nunó, 1854 |

| Adopted | September 16, 1854 1943 (anthem) |

| Audio sample | |

"Himno Nacional Mexicano" (instrumental, one verse)

| |

The "Mexican National Anthem" (Spanish: Himno Nacional Mexicano), also known by its incipit "Mexicans, at the cry of war" (Spanish: Mexicanos, al grito de guerra), is the national anthem of Mexico. The anthem was first used in 1854. The lyrics of the national anthem, which allude to historical Mexican military victories in the heat of battle and including cries of defending the homeland, were composed by poet Francisco González Bocanegra after a Federal contest in 1853. Later, in 1854, he asked Jaime Nunó to compose the music which now accompanies González's poem. The national anthem, consisting of ten stanzas and a chorus, effectively entered into use on September 16, 1854.

Composition

Lyrics competition

On November 12, 1853, President Antonio López de Santa Anna announced a competition to write a national anthem for Mexico. The competition offered a prize for the best poetic composition representing patriotic ideals. Francisco González Bocanegra, a talented poet, was not interested in participating in the competition. He argued that writing love poems involved very different skills from the ones required to write a national anthem. His fiancée, Guadalupe González del Pino (or Pili), had undaunted faith in her fiancé's poetic skills and was displeased with his constant refusal to participate in spite of her constant prodding and requests from their friends. Under false pretenses, she lured him to a secluded bedroom in her parents' house, locked him into the room, and refused to let him out until he produced an entry for the competition. Inside the room in which he was temporarily imprisoned were pictures depicting various events in Mexican history which helped to inspire his work. After four hours of fluent (albeit forced) inspiration, Francisco regained his freedom by slipping all ten verses of his creation under the door. After Francisco received approval from his fiancée and her father, he submitted the poem and won the competition by unanimous vote.[1][2] González was announced the winner in the publication Official Journal of the Federation (DOF) on February 3, 1854.

Music competition

A musical composition was chosen at the same time as the lyrics. The winner was Juan Bottesini, but his entry was disliked due to aesthetics. This rejection caused a second national contest to find music for the lyrics.[3] At the end of the second contest, the music that was chosen for González's lyrics was composed by Jaime Nunó, the then Catalonian-born King of Spain's band leader. At the time of the second anthem competition, Nunó was the leader of several Mexican military bands. He had been invited to direct these bands by President Santa Anna, whom he had met in Cuba. About the time that Nunó first came to Mexico to start performing with the bands, Santa Anna was making his announcement about creating a national anthem for Mexico. Nunó's anthem music composition was made like masterpieces of classical music, with a high quality in composition, and was chosen. Out of the few musical compositions submitted, Nunó's music, titled "God and Freedom" (Dios y libertad), was chosen as the winner on August 12, 1854.[4] The song was officially adopted as the Mexican national anthem on Independence Day, September 16 of that same year. The inaugural performance was directed by Juan Bottesini, sung by soprano Claudia Florenti and tenor Lorenzo Salvi at the Santa Anna Theatre.[3][5]

Lyrics

Officially since 1943, the full national anthem consists of the chorus and 1st, 5th, 6th, and 10th stanzas (with the chorus interspersed between each stanza and performed again at the end). The modification of the lyrics was ordered by President Manuel Ávila Camacho in a decree printed in the Diario Oficial de la Federación.[6] When the national anthem is played at sporting events such as the Olympic Games and the FIFA World Cup, an abridged form (chorus, stanza I, chorus) is used. An unofficial semi-abridged form (chorus, stanza I, chorus, stanza X, chorus) has gained some acceptance in television and radio programming.

|

Coro Mexicanos, al grito de guerra |

Chorus (English translation)[4] Mexicans, at the cry of war, |

Chorus (poetic translation)[7]

|

|

Estrofa I Ciña ¡oh Patria! tus sienes de oliva |

1st stanza Encircle Oh Motherland!, your temples with olives |

1st stanza Oh my country entwine on thy temples |

| Coro | Chorus | |

|

Estrofa V ¡Guerra, guerra! sin tregua al que intente |

Stanza V War, war! with no mercy to any who shall dare | |

| Coro | Chorus | |

|

Estrofa VI Antes, patria, que inermes tus hijos |

Stanza VI O, Motherland, if however your children, defenseless | |

| Coro | Chorus | |

|

Estrofa X ¡Patria! ¡Patria! Tus hijos te juran |

Stanza X Motherland! Motherland! Your children assure |

Copyright status

An urban legend about the copyright status of the anthem states that years after its first performance, family sold the musical rights to a German music publishing company named Wagner House. Originally, Nunó was supposed to have turned the music rights over to the state in exchange for a prize from the Mexican government. However, according to the myth, the copyright changed hands again, this time to Nunó himself and two Americans, Harry Henneman and Phil Hill.[8]

In reality, this is not correct. It is true that Nunó, Henneman and Hill did register the music with the company BMI (BMI Work #568879), with the Edward B. Marks Music Company as the listed publisher of the anthem.[9] This might be the version that some have suggested is copyrighted in the United States.[10] However, United States copyright law declares the Mexican anthem to be in the public domain inside the United States, since both the lyrics and music were published before 1923.[11] Furthermore, under Mexican copyright law, Article 155 states that the government holds moral rights, but not property rights, to symbols of the state, such as the national anthem, coat of arms and the national flag.[12]

National regulations

In the second chapter of the Law on the National Arms, Flag, and Anthem (Ley sobre el Escudo, la Bandera y el Himno Nacionales), the national anthem is described in very brief terms. While Articles 2 and 3 discuss in detail the coat of arms and the flag, respectively, Article 4 mentions only that the national anthem will be designated by law. Article 4 also mentions that a copy of the lyrics and the musical notation will be kept at two locations, the General National Archive and at the National Library, located in the National Museum of History (Biblioteca Nacional en el Museo Nacional de Historia).[13]

Chapter 5 of the Law goes into more detail about how to honor, respect and properly perform the national anthem. Article 38 states that the singing, playing, reproduction and circulation of the national anthem are regulated by law and that any interpretation of the anthem must be performed in a "respectful way and in a scope that allows [one] to observe the due solemnity" of the anthem. Article 39 prohibits the anthem from being altered in any fashion, prohibits it from being sung for commercial or promotional purposes, and also disallows the singing or playing of national anthems from other nations, unless you have permission from the Secretary of the Interior (Secretaría de Gobernación) and the diplomatic official from the nation in question. The Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary of Public Education (Secretaría de Educación Pública), in Article 40, must grant permission for all reproductions of the national anthem to be produced, unless the anthem is being played during official ceremonies carried on radio or television. Article 41 states that the national anthem is required to be played at the sign-on or sign-off of radio and television programming; with the advent of 24-hour programming schedules in the 1990s and 2000s, many stations now do so at or as close to midnight and 6 a.m. local time as possible by interpretation of the former traditional times of sign-on and sign-off. The extra requirement for television programming is that photos of the Mexican flag must be displayed at the same time the anthem is playing.

Article 42 states that the anthem may only be used during the following occasions: solemn acts of official, civic, cultural, scholastic or sport character. The anthem can also be played to render honors to the Mexican flag and to the President of Mexico. If the national anthem is being used to honor the national flag or the President, the short version of the anthem is played. Article 43 says that special musical honors may be paid to the President and the flag, but no more than once during the same ceremony. Article 44 says that during solemn occasions, if a choir is singing the anthem, the military bands will keep silent. Article 45 says that those who are watching the national anthem performance must stand at attention (firmes) and remove any headgear. Article 46 states that the national anthem must be taught to children who are attending primary or secondary school; this article was amended in 2005 to add pre-school to the list. The article also states that each school in the National Education System (Sistema Educativo Nacional) will be asked to sing the national anthem each year. Article 47 states that in an official ceremony in which is need to play another anthem, the Mexican anthem will be played first, then the guest state's national anthem. Article 48 states that at embassies and consulates of Mexico, the national anthem is played at ceremonies of a solemn nature that involves the Mexican people. If the anthem is played outside of Mexico, Article 48 requires that the Secretary of External Relations (Secretaría de Relaciones Exteriores), through proper channels, must grant permission for the national anthem to be played and will also ensure that the anthem is not sung for commercial purposes.[13]

Cultural significance

At the time the Mexican national anthem was written, Mexico was still facing the effects of a bitter defeat in the Mexican–American War at the hands of the United States. The country felt demoralized and also divided, due to the cession of more than half of its territory due to its defeat to the United States. According to historian Javier Garciadiego, who spoke at a 2004 ceremony commemorating the 150th anniversary of the national anthem's adoption, the song disregards divisions and strife and encourages national unity. On that same date, Mexico City and other parts of the country stopped what they were doing and performed a nationwide singing of the national anthem. Individuals from other countries also participated, mostly at diplomatic offices or at locations where a high concentration of Mexican expatriates are found. The national anthem has also been described as one of the symbols of the "Mexican identity".[10]

On the rare occasions when someone performs the national anthem incorrectly, the federal government has been known to impose penalties to maintain the "dignity" of the national symbols. One example is when a performer forgot some of the lyrics at a association football match in Guadalajara, she was fined $400 MXN by the Interior Ministry and released an apology letter to the country through the Interior Ministry.[14] Another infamous case is that of banda musician Julio Preciado, who performed the national anthem at the inauguration of the Caribbean Baseball Series in 2009; El Universal reported that "in a slow tone that has nothing to do with the rhythm of the National Anthem, the singer literally forgot the lyrics of the second stanza and mixed it with others",[15] this earned the fanfare of those who were present at the stadium (and those watching it live on TV), some of the people attending the inauguration started shouting the phrases "¡sáquenlo!, ¡no se lo sabe! ¡fuera, fuera!" (Get him out! He doesn't know it! Out, out!).

In addition, the national anthem is sometimes used as a kind of shibboleth: a tool against people who might not be "true Mexicans" (a "fake Mexican" being a migrant from another Latin American country, who pretends that he or she is from Mexico. The suspected are asked to sing Mexico's national anthem and it is widely expected that only "true Mexicans" will know the lyrics and tune and thus will be able to sing it. In one case, a young man of Afro-Mexican descent was stopped by police and forced to sing the national anthem to prove his nationality.[16] In a separate incident in Japan, police officers asked four men to sing the Mexican national anthem after they were arrested in Tokyo on charges of breaking and entering. However, when the men could not sing the song, it was discovered that they were Colombians holding forged Mexican passports. They were later charged with more counts on theft of merchandise and money.[17]

Other languages

Though the de facto language of Mexico is Spanish, there are still people who only speak indigenous languages. On December 8, 2005, Article 39 of the national symbols law was adopted to allow for the translation of the lyrics into the native languages. The official translation is performed by the National Institute of Indigenous Languages (Instituto Nacional de Lenguas Indígenas).[18]

Officially, the national anthem has been translated into the following native languages: Chinanteco, Hña Hñu, Mixteco, Maya, Nahuatl and Tenek. Other native groups have translated the anthem into their respective language, but it has not been sanctioned by the Government.[19]

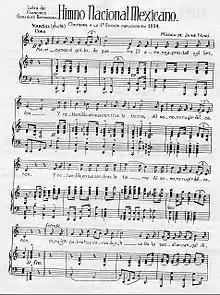

Musical score

Second page of music and lyrics

Second page of music and lyrics

References

- David Kendall National Anthems—Mexico

- Galindo y Villa, Jesus (1907). Anales del Museo Nacional de Mexico, 1907. Mexico: Imprenta de Museo Nacional. p. 456-457.

- Embassy of Mexico in Serbia and Montenegro Mexican Symbols—Himo. Retrieved March 19, 2006. Archived February 22, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "National Anthem for Kids". Archived from the original on April 29, 2006. Retrieved March 15, 2006.

- Secretary of External Relations History of the Mexican Anthem. Retrieved March 15, 2006. (in Spanish)

- Administration of Ernesto Zedillo National Symbols of Mexico Archived 2006-04-25 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved March 15, 2006.

- "Indianapolis News 15 September 1917 — Hoosier State Chronicles: Indiana's Digital Historic Newspaper Program". newspapers.library.in.gov. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- LA Weekly DON'T CRY FOR ME, MEXICO; Article about the copyright situation. September 22, 1999.

- BMI Repretoire Himno Nacional Mexicano (BMI Work #568879). Retrieved March 16, 2006.

- San Diego Union Tribune Mexicans celebrate 150 years of national anthem with worldwide sing-along Archived 2007-03-13 at the Wayback Machine September 15, 2004. Retrieved March 15, 2006.

- US Copyright Office Copyright Term and the Public Domain in the United States. Retrieved March 16, 2006. Archived July 4, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Secretary of Education Mexican Copyright Law. Retrieved March 15, 2006 (in Spanish) Archived February 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "Ley sobre el Escudo la Bandera y el Himno Nacionales" (PDF) (in Spanish). Government of Mexico. 2006-06-03. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 19, 2009. Retrieved 2010-03-01.

- Associated Press "Woman fined for bungling Mexican anthem". Archived from the original on June 28, 2012.. October 2004. Retrieved March 20, 2006.

- "Julio Preciado se equivoca al entonar el Himno Nacional (in Spanish)". El Universal. 2009. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- College Street Journal FP Antonieta Gimeno Attends Conference on Black Mexicans Archived 2009-04-29 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved March 20, 2006.

- ABC News Online Japanese police catch Colombian thieves out. June 15, 2004. Retrieved March 20, 2006.

- Diario Oficial de la Federación—Decree allowing for translation of the anthem into native languages. December 7, 2005. Retrieved January 11, 2006.

- Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de los Pueblos Indígenas Himno Nacional Mexicano en lenguas indígenas

External links

| Spanish Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mexicanos, al grito de guerra. |

- President of Mexico's page about the anthem, with two recordings (in Spanish)

- Free sheet music of Himno Nacional Mexicano from Cantorion.org

- Broadcast closure of Televisa Televisa's former broadcast closure

- Descargas de Videos y audios