History of soccer in the United States

The history of soccer in the United States has numerous different roots. Recent research has shown that the modern game entered America in the 1850s through New Orleans when Scottish, Irish, German and Italian immigrants brought the game with them. It was in New Orleans that some of the first organized games that used modern English rules were held.[1]

Men's soccer

Early versions of football were being played in the United States as early as 1685, and freshmen at Harvard University in 1734 were asked to provide "foot-balls". This did not resemble modern soccer in any way, except that it involved various kicking activities, and was often violent. By the 1860s, several different sets of rules began to be codified, such as the "Boston Game" which was like a hybrid of rugby and soccer.[2]:17–20

Club soccer

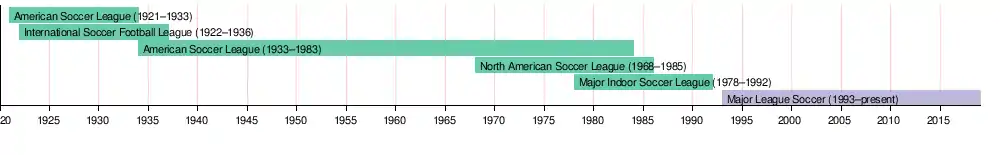

- Timeline of a few of the known soccer leagues in the United States

Active Leagues Folded Leagues

Oneida Football Club, and other organized teams

The Oneida Football Club was established in 1862 by Gerrit Smith "Gat" Miller, a graduate of the Latin School of Epes Sargent Dixwell, a private college preparatory school in Boston.[3] At the time there were no formal rules for football games, with different schools and areas playing their own variations. This informal style of play was often chaotic and very violent, and Miller had been a star of the game while attending Dixwell. However, he grew tired of these disorganized games, and organized other recent preparatory school graduates to join what would be the first organized football team in the United States.

The team consisted of a group of Boston secondary school students from relatively elite public (state) schools in the area, such as Boston Latin School and the English High School of Boston. Organization served the club well, and it reportedly never lost a game, or even allowed a single goal.

Football at universities

The 1869 New Jersey vs. Rutgers football game is often cited to be the birth of intercollegiate American football, but it also considered the birth of soccer in the United States as well,[lower-alpha 1] as it was played with rules based on the Football Association's (FA) first set of rules. Although American football began to take hold at eastern universities such as Harvard, Princeton, and Yale, "socker" gained popularity at Haverford, Columbia, Cornell, and Penn.[2]:24 These enthusiasts arranged for English teams to tour the United States to generate interest in the sport in 1905, 1907, and 1909. Nevertheless, American football became the primary sport at most schools.[2]:25–26

Immigrant communities

Soccer was popular among communities with large immigrant populations. Many towns in the West Hudson area of New Jersey, such as Kearny and Paterson, both of which had textile factories established and staffed by British companies. Residents of these areas founded the National Association Football League in 1895.[2]:27–28

Another notable location was centered around Fall River, Massachusetts, which also had textile companies and many immigrants from England. This area had the Bristol County League in 1886 and the Southern New England League in 1914.[2]:28

The third major location was St. Louis, Missouri, where the Catholic Church was primarily responsible for introducing soccer into its recreational programs. The St. Louis League was founded in 1886 and modified the FA's rules to its own liking, as did the St. Louis Soccer League, founded in 1903.[2]:28–29

Other communities where soccer had taken hold were Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit, Cincinnati, Cleveland, San Francisco, and Los Angeles.[2]:30

Attempts at a governing body

Before the creation of the United States Soccer Federation, soccer in the United States was organized on regional levels, with no governing body overlooking regional soccer leagues. The first non-league organizing body within the United States was the American Football Association (AFA) which was incarnated in 1884. The AFA sought to standardize rules for teams competing in northern New Jersey and southern New York. Within two years, this region began to widen to include teams in Pennsylvania and Massachusetts and Texas.[4]

A professional league was established by owners of several Major League Baseball teams in 1894, called the American League of Professional Foot Ball (ALPFB), in an attempt to generate revenue during the winter months when their ballparks were empty. The AFA was displeased with the idea and banned any of its players that signed contracts with ALPFB teams. Despite the financial backing they had, the ALPFB failed to generate much interest and the league folded after only 17 days.[2]:31–32

USFA vs. AFA, FIFA sanctioning

Within a year of its founding, the AFA organized the first non-league cup in U.S. soccer history, known as the American Cup. Clubs from New Jersey and Massachusetts dominated the first twelve years. However, beginning in 1894, due to economic conditions and labor unrest, teams in the Fall River area were forced to withdraw as many of them were sponsored the textile companies. Furthermore, players that had signed for the ALPFB teams were forbidden to play. As a result, the AFA suspended the cup in 1899, and it was not resumed until 1906 as a result of the interest generated by the English tour in 1905.[5]:31[2]:31–32

In October 1911, a competing body, the American Amateur Football Association (AAFA) was created. The association quickly spread outside of the Northeast and created its own cup in 1912, the American Amateur Football Association Cup.

In 1912, both the AFA and AAFA applied for membership in FIFA, the international governing body for soccer. Drawing on both its position as the oldest soccer organization and the status of the American Cup, the AFA argued that it should be the nationally recognized body. FIFA refused to recognize either of them, telling them there only needed to be a single group that could represent the United States.[2]:33

In 1913, the AAFA gained an edge over the AFA when several AFA organizations moved to the AAFA. On April 5, 1913, the AAFA reorganized as the United States Football Association. FIFA quickly granted a provisional membership and USFA began exerting its influence on the sport. This led to the establishment of the National Challenge Cup that fall. The National Challenge Cup quickly grew to overshadow the American Cup. However, both cups were played simultaneously for the next ten years. Declining respect for the AFA led to the withdrawal of several associations from its cup in 1917. Further competition came in 1924 when USFA created the National Amateur Cup. That spelled the death knell for the American Cup. It played its last season in 1924.

Soccer Wars

Towards the end of the 1920s, a period in American soccer known as the "American Soccer Wars" ignited. The Soccer Wars regarded the internal conflicts with the American Soccer League and their affiliated clubs participating in the National Challenge Cup. The debate involved whether the United States Football Association or the American Soccer League was the true chief organization of American soccer at the time, and consequently wrecked the reputation and possibly even the popularity of the sport domestically. The colloquial "war" has been considered responsible for the fall of the ASL, and the end to the first golden age of American soccer.[6]

The initial issue with the ASL had been the scheduling of the National Challenge Cup, which had been straining for the ASL season schedule. Typically, the National Challenge Cup had been played during the ASL's offseason, which made it difficult for ASL clubs to compete in the tournament. Consequently, the ASL boycotted the 1925 Challenge Cup due to scheduling conflicts, and the lack of cooperation the USFA inflicted on the ASL. American soccer historians claim that the real issue was the ASL vying to be the premier soccer body in the United States.[6]

In 1927, the issue intensified as ASL clubs were accused by FIFA for signing European players who were already under contract to European clubs. Due to the conflict and apparent corruption in the ASL, USFA president (at the time), Andrew M. Brown traveled to Helsinki, Finland for the 1927 FIFA Congress in the hopes of removing any penalties imposed on the ASL and USFA.[6] Other issues regarding the soccer league involved the closed league model and the lack of American soccer players dominating the league. It resulted in ASL owners wanting to run their soccer clubs more like Major League Baseball teams, as many ASL owners owned MLB franchises. According to owners of ASL clubs, they saw these rulings as restrictions imposed on themselves, including the National Challenge Cup.[7]

With the hope of breaking away from the National Challenge Cup, Charles Stoneham,[6] an owner of the New York Nationals proposed that the ASL would create their own tournament to determine the champion of the ASL, and thus ultimately determine the top American soccer club. This was the creation of early forms of playoffs culminating a regular season. Additionally, the proposal included expanding into the Midwest to include clubs from the Ohio River Valley and St. Louis regions, and create a new division for these clubs. Stoneham's plan involved having the two divisions compete in their own season, and the top clubs in each division playing in the ASL tournament to determine the ASL champion. Before the proposal, the National Challenge Cup was seen as the ultimate title in American soccer since most professional leagues in the United States focused on a specific region, rather than encompassing the entire country as a whole.[6]

The problem with this system was the fact that the American Soccer League was operating under a closed league model with a fixed number of franchises.[7] This new tournament, or playoffs, would permanently cap the number of clubs entering this premier competition, unlike the National Challenge Cup, which the tournament was open to any USFA-affiliated team. Due to such reasons, three teams, Bethlehem Steel, the New York Giants S.C. and the Newark Skeeters, rejected the proposal, played in the 1928 National Challenge Cup[8] and were subsequently suspended from the league and fined $1,000.[6][7] Hence the ASL's decision, the USFA suspended the ASL which ignited the "Soccer Wars".[9][10] In the 1928–29 American Soccer League, the Steel, Giants and Skeeters did not play in the ASL and joined local semi-professional leagues agglommerating to form the Eastern Professional Soccer League.[9]

Support for the USFA from other national federations, along with financial disadvantages the ASL faced as an unsanctioned league, eventually convinced the ASL that it could not win this "soccer war" and should yield. The "war" between the USFA and ASL was finally settled in early October 1929.[6] During that time the ASL had already begun its 1929–30 season, halted during the settlement.[9] Thanks to the settlement, the ASL was assembled back together, and played the remainder of the 1929–30 year until the moniker "Atlantic Coast League".[11]

Decline of sport, amateur era

.jpg.webp)

Just two weeks following the United States Football Association and American Soccer League settlement, the stock market crashed. The abrupt and intense economic impact drastically affected the ASL in the league's Spring 1930 season, in which several clubs defaulted during the season, and clubs did not finish the season with the same number of matches played. Initially, the struggles in ASL did not affect the league's stronger clubs, as the Fall River Marksmen completed the double by winning both the 1930 season and the 1930 National Challenge Cup.[12]

As the Great Depression intensified, the original ASL folded following the Fall 1932 season, which was its 15th season in existence. At the apex of the Depression, several surviving clubs created an incarnation of the ASL which began play in 1933, but the stringent economy suffered the ability for ASL teams to field strong teams, and caused teams to not have the financial means nor interest to attract foreign players. This consequently caused a Dark Age of soccer in which the sport as well as the National Challenge Cup fell out of popularity and into obscurity.[13]

In spite of the decline in the sport's popularity, in several pockets of the country, primarily the Heartland and New England regions, as well as the New York City and St. Louis metropolitan areas, soccer continued to be extremely popular, especially with ethnic groups and expatriates. The popularity of soccer in these areas reflected on the Challenge Cup during the later Great Depression years, through the World War II years. Most clubs participating were either top amateur teams or semi-professional clubs that hoisted a handful of U.S. internationals, who worked part-time jobs.

Rise of the original NASL

In 1967, two professional soccer leagues started in the United States: the FIFA-sanctioned United Soccer Association, which consisted of entire European and South American teams brought to the US and given local names, and the unsanctioned National Professional Soccer League. The National Professional Soccer League had a national television contract in the U.S. with the CBS television network, but the ratings for matches were unacceptable even by weekend daytime standards and the arrangement was terminated. The leagues merged in 1968 to form the North American Soccer League (NASL). It has been suggested that the timing of the merger was related to the huge amount of attention given throughout the English-speaking world to the victory by England in the 1966 FIFA World Cup and the resulting documentary film, Goal.[14] The league lasted until the 1984 NASL season.

Pele and the New York Cosmos

The biggest club in the league and the organization's bellwether was the New York Cosmos, who drew upwards of 40,000 fans per game at their height while aging superstars Pelé (Brazil) and Franz Beckenbauer (Germany) played for them. Although both were past their prime by the time they joined the NASL, the two were considered to have previously been the best attacking (offensive) (Pelé) and defensive (Beckenbauer) players in the world. Giants Stadium sold out (73,000+) their 1978 championship win.

Decline and collapse of the NASL

Over-expansion was a huge factor in the death of the league. Once the league started growing, new franchises were awarded quickly, and it doubled in size in a few years, peaking at 24 teams. Many have suggested that cash-starved existing owners longed for their share of the expansion fee charged of new owners, even though Forbes Magazine reported this amount as being only $100,000. This resulted in the available personnel being spread too thinly, among other problems. Additionally, many of these new owners were not "soccer people", and once the perceived popularity started to decline, they got out as quickly as they got in. They also spent millions on aging stars to try to match the success of the Cosmos, and lost significant amounts of money in doing so.

Also, FIFA's decision to award the hosting of the 1986 FIFA World Cup to Mexico after Colombia withdrew, rather than the U.S., is considered a factor in the NASL's demise.

On March 28, 1985, the NASL suspended operations for the 1985 season, when only the Minnesota Strikers and Toronto Blizzard were interested in playing.

Modern professional age

Men's national team

1930s

In the 1930 World Cup, the U.S. finished third, beating Belgium 3–0 at Estadio Gran Parque Central in Montevideo, Uruguay. The match occurred simultaneously with another across town at Estadio Pocitos where France defeated Mexico.

In the next match, the United States earned a 3–0 victory over Paraguay. For many years, FIFA credited Bert Patenaude with the first and third goals and his teammate Tom Florie with the second.[15] Other sources described the second goal as having been scored by Patenaude[16][17] or by Paraguayan Ramon Gonzales.[18] In November 2006, FIFA announced that it had accepted evidence from "various historians and football fans" that Patenaude scored all three goals, and was thus the first person to score a hat trick in a World Cup finals tournament.[19]

Having reached the semifinals with the two wins, the American side lost 6–1 to Argentina. Using the overall tournament records, FIFA credited the U.S. with a third-place finish ahead of fellow semi-finalist Yugoslavia.[20] The finish remains the team's best World Cup result and is the highest finish of any team from outside of CONMEBOL and UEFA, the South American and European confederations, respectively.

Due to FIFA not wanting interference with the newly founded FIFA World Cup no official tournament was fielded in the 1932 Olympic Games . FIFA claimed the tournament would not be popular in the United States, so it would not be cost efficient to assist in the running of the tournament during struggling economic times. As a result, an informal tournament was organized including local rivals with the United States finishing first, followed by Mexico and Canada. The Olympic Tournament was reinstated in the 1936 Olympic Games.

1970s–1990s

After the enthusiasm caused by the creation and rise of the North American Soccer League in the 1970s, it seemed as though the U.S. men's national team would soon become a powerful force in world soccer. Such hopes were not realized, however, and the United States was not considered a strong side in this era.

From 1981 to 1983, only two international matches were played. To provide a more stable national team program and renew interest in the NASL, U.S. Soccer entered the national team into the league for the 1983 season as Team America. This team lacked the continuity and regularity of training that conventional clubs enjoy, and many players were unwilling to play for the team instead of their own clubs. Embarrassingly, Team America finished the season at the bottom of the league. Recognizing that it had not achieved its objectives, U.S Soccer canceled this experiment, and the national team was withdrawn from the NASL.

U.S. Soccer made the decision to target the 1984 Summer Olympics in Los Angeles, California and the 1986 World Cup as means of rebuilding the national team and its fan base. The International Olympic Committee declared that teams from outside Europe and South America could field full senior teams, including professionals (until then, the amateur-only rule had heavily favored socialist countries from Eastern Europe whose players were professionals in all but name). The U.S. had a very strong showing at the tournament, beating Costa Rica, tying Egypt, losing only to favorite Italy and finishing 1–1–1 but didn't make the second round, losing to Egypt on a tiebreaker (both had three points).

By the end of 1984, the NASL had folded and there was no senior outdoor soccer league operating in the United States.[21] As a result, many top American players, such as John Kerr, Paul Caligiuri, Eric Eichmann, and Bruce Murray, moved overseas, primarily to Europe.

The United States did bid to host the 1986 World Cup after Colombia withdrew due to economic concerns. However, Mexico beat out the U.S. and Canada to host the tournament, despite concerns that the tournament would have to be moved again because of a major earthquake that hit Mexico shortly before the tournament.

In the last game of the qualifying tournament, the U.S. needed only a draw against Costa Rica, whom the U.S. had beaten 3–0 in the Olympics the year before, in order to reach the final qualification group against Honduras and Canada. U.S. Soccer scheduled the game to be played at El Camino College in Torrance, California, an area with many Costa Rican expatriates, and marketed the game almost exclusively to the Costa Rican community, even providing Costa Rican folk dances as halftime entertainment.[22] A 35th-minute goal by Evaristo Coronado won the match for Costa Rica and kept the United States from reaching its fourth World Cup finals.

In 1988, U.S. Soccer attempted to re-implement its national-team-as-club concept, offering contracts to national team players in order to build an international team with something of a club ethos, while loaning them out to their club teams, saving U.S. Soccer the expense of their salaries. This brought many key veterans back to the team, while the success of the NASL a decade earlier had created an influx of talent from burgeoning grass-roots level clubs and youth programs. Thus U.S. Soccer sought to establish a more stable foundation for participation in the 1990 World Cup than had existed for previous tournaments.

2000–present

After failing to maintain his 2002 success at the 2006 World Cup, Bruce Arena was eventually replaced by his assistant with the national team and Chivas USA manager, Bob Bradley, whose reign began with four wins and one draw in friendlies leading up to the 2007 Gold Cup, hosted by the United States.

The U.S. won all three of its group stage matches, against Guatemala, Trinidad and Tobago, and El Salvador. With a 2–1 win over Panama in the quarterfinals, the U.S. advanced to face Canada in the semifinals, winning 2–1. In the final, the United States came from behind to beat Mexico 2–1.[23]

The team's disappointing Copa América 2007 campaign ended after three defeats in the group stage to Argentina, Paraguay, and Colombia. The decision by U.S. Soccer to field what many considered a second-tier team was questioned by fans and media alike.[24]

One of the hallmarks of Bradley's tenure as national team manager has been his willingness to cap a large number of players, many for their first time. This practice has been praised by those wanting to see a more diverse player pool for the national team, as well as criticized by those hoping for more consistency and leadership from core players.[25] This has coincided with many young American players like Freddy Adu, Jozy Altidore, Clint Dempsey, Maurice Edu, Brad Guzan, Eddie Johnson, and Michael Parkhurst making their first moves from MLS to European clubs, meaning that more American players are gaining experience at the highest levels of club and international soccer than at any other time in the team's history.

In Summer 2009, the United States had one of the busiest stretches in its history. For the 2009 Confederations Cup the U.S. was drawn into Group B with Brazil, Egypt, and Italy. After losing 3–1 to Italy and 3–0 to Brazil, the United States made an unlikely comeback to finish second in the group and reach the semi-final on the second tie-breaker, goals scored, having scored four goals to Italy's three. This was achieved on the final day of group play when the United States beat Egypt 3–0 while Brazil beat Italy 3–0.[26]

In the semifinals, the U.S. defeated Spain 2–0.[27] At the time, Spain was atop the FIFA World Rankings and was on a record run of 15 straight wins and 35 games undefeated (a record shared with Brazil). With the win, the United States advanced to its first-ever final in a men's FIFA tournament; however, the team lost 3–2 to Brazil after leading 2–0 at half-time.[28]

Only a few days after the Confederations Cup Final, the United States hosted the 2009 Gold Cup, and was drawn into Group B with Grenada, Haiti, and Honduras. Due to the fact that the U.S. had just played in the Confederations Cup and still had half of its World Cup qualifying campaign to go, Bob Bradley chose a side consisting of mostly reserves who had never really played together on the international stage and was criticized for selecting a "B Side" for the Continental tournament.[29] The U.S. began group play with a pair of victories over Grenada and Honduras, and won the group with a draw against Haiti.

In the quarterfinals, the United States defeated Panama 2–1 after extra time. In the semifinals the U.S. faced Honduras for the second time in the tournament, and the third time in less than two months. The United States beat Honduras 2–0 and advanced to its third consecutive Gold Cup final where the team faced Mexico in a rematch of the 2007 Gold Cup final. The United States was beaten by Mexico 5–0, surrendering its 58-match unbeaten streak against CONCACAF opponents on U.S. soil. It was also the first home loss to Mexico since 1999.

The United States qualified for the 2010 FIFA World Cup atop their group, and they were drawn into Group C with England, Slovenia, and Algeria. Despite an early goal by Steven Gerrard, the USA drew 1–1 with England in their first match after a sloppy save by Rob Green off Clint Dempsey bounced off his hands and rolled into the goal. Against Slovenia, the United States found themselves down 2–0 quickly, and managed to tie the game at 2–2. They would have won, except a Michael Bradley goal was wrongly disallowed, and the game ended at the 2–2 scoreline. In their third and final group stage game against Algeria, Landon Donovan scored in the 91st minute to win the game 1–0 for the US, winning the group. They played Ghana next, where they lost in Extra Time 2–1 and bowed out of the tournament.

The 2011 CONCACAF Gold Cup was supposed to be a rebound for the United States, and for a time they looked to do very well. When they reached the Final, they found themselves against Mexico, where they went up 2–0 at halftime. However, they let the lead slip and lost 3–2. After this defeat, Bob Bradley was relieved of his position as manager. Not long after, Jürgen Klinsmann, former Bayern Munich and Germany manager, was hired.

Under Klinsmann's leadership, the 2014 FIFA World Cup qualifying cycle went very well for the United States, as did the friendlies during that period. The United States defeated Mexico 1–0 in the Azteca Stadium for the first time in history in 2012. The United States also defeated Italy in Italy, at the time the number 3 team in the world, marking it the first time in history the USA defeated a Top 4 opponent on their soil. The second stage of CONCACAF World Cup Qualification ended with the USA topping its group of 4, Jamaica taking 2nd.

In 2013, the United States had a record year. It started poorly, with a 2–1 loss to Honduras in San Pedro Sula, but the United States rebounded to defeat Costa Rica in Denver 1–0 in a match dubbed the "Show Clasico," followed by the United States drawing Mexico in Azteca and earning the second qualification point in Mexico in history. The United States continued its strong run through June, defeating Germany 4–2 in the Centennial Match, and Jamaica, Panama, and Honduras to take a commanding lead of the Hex. The 2013 CONCACAF Gold Cup took place at this point, and the United States fielded a younger team of players who were attempting to win their way into the senior squad, including Landon Donovan who was coming off of a sabbatical from the sport at the time. The United States won every game they played in the tournament, defeating Panama 1–0 in the Final to take the cup. The United States continued its win streak by defeating Bosnia-Herzegovina, but lost to Belgium to end their win streak at 13. The USA lost to Costa Rica, but defeated Mexico 2–0 in the Hex to seal a trip to the 2014 FIFA World Cup. The United States then ended their year strong, defeating Jamaica and Panama to close out 2013, and Klinsmann was given a 4-year extension to his contract.

2014 brought Klinsmann's first World Cup with the United States, in which they were drawn in a "Group of Death" in Group G, alongside Germany, Portugal, and Ghana. Controversy marked the USA's entry, with the exclusion of Landon Donovan from the roster, with many believing Julian Green had been brought on at Donovan's expense. The USA entered the World Cup on a 3-game win streak from their send-off series. They defeated Ghana 2–1 off of a header from John Brooks in the 89th minute, and then played Portugal. The United States looked to have defeated Portugal and to have sealed a place in the knockout stages, but in stoppage time, Portugal scored a goal to end the game 2–2. The United States then played Germany and lost 1–0, but did escape group on goal difference. They were defeated by Belgium 2–1 in extra time after a heroic effort by Tim Howard, in which Howard set a World Cup record of 16 saves in a single match.

The United States exited 2014 shakily, as opposed to their entry. In early September, Landon Donovan played his farewell match, and for a few months after, the USA failed to earn a win until a friendly against Panama.

The United States finished in fifth place in the final round of the qualifying cycle for the 2018 FIFA World Cup, which concluded in October 2017; due to this result, the team failed to qualify for the World Cup for the first time since 1986.

Women's soccer

Amateur Soccer: W-League and WPSL

Originally called the United States Interregional Women's League, the W-League was formed in 1995 as the first national women's soccer league, providing a professional outlet for many of the top female soccer players in the country. Starting as the Western Division of the W-League, the Women's Premier Soccer League broke away and formed its own league in 1997 and had its inaugural season in 1998. Both the W-League and the WPSL were considered the premier women's soccer leagues in the United States at the time, but eventually fell to a “second-tier” level upon the formation of the Women's United Soccer Association in 2000.

Women's United Soccer Association (2000–2003)

As a result of the US Women's National Team's (USWNT) first-place showing in the 1999 FIFA Women's World Cup, a seemingly viable market for the sport germinated. Feeding on the momentum of their victory, the twenty USWNT players, in partnership with John Hendricks of the Discovery Channel, sought out the investors, markets, and players necessary to form the eight-team league in February 2000, playing its first season in April 2001. It would be the world's first women's soccer league in which all the players were paid as professionals. The eight teams included the Atlanta Beat, Boston Breakers, Carolina Courage, New York Power, Philadelphia Charge, San Diego Spirit, San Jose CyberRays (called Bay Area CyberRays for 2001 season), and the Washington Freedom.

The US Soccer Federation approved membership of the WUSA as a sanctioned Division 1 women's professional soccer league on August 18, 2000. The WUSA has previously announced plans to begin play in 2001 in eight cities across the country, including: Atlanta, the Bay Area, Boston, New York, Orlando, Philadelphia, San Diego and Washington, D.C. Led by investor John Hendricks, the WUSA has also forged ahead on a cooperation agreement that will see the new league work side by side with Major League Soccer to help maximize the market presence and success of both Division I leagues.[30]

The WUSA played for three full seasons and suspended operations on September 15, 2003, shortly after the conclusion of the third season due to financial problems and lack of public interest in the sport.[31]

Post-WUSA (2004–2009)

With the WUSA on hiatus, the Women's Premier Soccer League (WPSL) and the W-League regained their status as the premier women's soccer leagues in the United States, and many former WUSA players joined those teams. The Washington Freedom was the only WUSA team to continue operations after the league dissolved (although new versions of the Atlanta Beat and Boston Breakers formed in 2009) and eventually became a part of the W-League in 2006. After the folding of WUSA, WUSA Reorganization Committee was formed in September 2003 that led to the founding of Women's Soccer Initiative, Inc. (WSII), whose stated goal was "promoting and supporting all aspects of women's soccer in the United States", including the founding of a new professional league.[32] Initial plans were to play a scaled down version of WUSA in 2004. However, these plans fell through and instead, in June 2004, the WUSA held two "WUSA Festivals" in Los Angeles and Blaine, Minnesota, featuring matches between reconstituted WUSA teams in order to maintain the league in the public eye and sustain interest in women's professional soccer.[33] A planned full relaunch in 2005 also fell through. In June 2006, WSII announced the relaunch of the league for the 2008 season.[34]

In December 2006, WSII announced that it reached an agreement with six owner-operators for teams based in Chicago, Dallas, Los Angeles, St. Louis, Washington, DC, and a then-unnamed city.[35] In September 2007, the launch was pushed back from Spring of 2008 to 2009 to avoid clashing with 2007 Women's World Cup and the 2008 Olympic Games and to ensure that all of the teams were fully prepared for long-term operations.[36]

Women's Professional Soccer (2009–2012)

The name for the new professional league, along with its logo, was announced on January 17, 2008.[37] The league was to have its inaugural season in 2009, with seven teams, including the Washington Freedom, a former WUSA team. Twenty-one US national team players were allocated to each of the seven teams in September 2008. Also in September, the league held the 2008 WPS International Draft. Unlike WUSA, the WPS took "a local, grass roots approach", and "a slow and steady growth type of approach.”[38] In addition, the WPS attempted to have a closer relationship with Major League Soccer in order to cut costs.

The seven teams that played in the inaugural season of the WPS were the Boston Breakers, Chicago Red Stars, FC Gold Pride, Los Angeles Sol, magicJack (originally Washington Freedom), Sky Blue FC, and Saint Louis Athletica. Most teams considered the first season a moderate success, despite many losing more money than planned. However, most teams began to see problems in 2010. Overall attendance for 2010 was noticeably down from 2009, teams were struggling with financial problems, and the WPS changed leadership by the end of the season. The success of the United States women's national soccer team at the 2011 FIFA Women's World Cup resulted in an upsurge in attendance league-wide as well as interest in new teams for the 2012 season.[39] However, several internal organization struggles, including an ongoing legal battle with magicJack-owner Dan Borislow,[40] and lack of resources invested in the league lead to the suspension of the 2012, announced in January 2012.[41]

On May 18, 2012 the WPS announced that the league had officially ceased operations, having played for only three seasons.[42]

WPSL Elite (2012)

Up until 2012, the WPSL and W-League were the two semi-pro leagues in the United States and had sat under WUSA and the WPS. Upon the disbandment of the WPS, they once again regained their status as the premier women's soccer leagues in the United States. In response to the suspension, and eventual end, of the WPS, the Women's Premier Soccer League created the Women's Premier Soccer League Elite (WPSL Elite) to support the sport in the United States. For the 2012 season, the league featured former WPS teams, Boston Breakers, Chicago Red Stars, and Western New York Flash, in addition to many WPSL teams. Six of the eight teams were considered fully professional.[43] Many members of the USWNT remained unattached for the 2012 season while others chose to play in the W-League instead of the WPSL Elite.

National Women's Soccer League (2013–present)

After the WPS folded in 2012, the United States Soccer Federation (USSF) announced a roundtable for discussion of the future of women's professional soccer in the United States, leading to the creation of the National Women's Soccer League (NWSL). The meeting resulted in the planning of a new league set to launch in 2013 with 12–16 teams, taking from the WPS, the W-League, and the WPSL.[44] In November 2012, it was announced that there would be eight teams in a new women's professional soccer league. The league would be funded by the USSF, the Canadian Soccer Association (CSA) and the Mexican Football Federation (FMF). USSF would fund up to 24 players, the CSA up to 16, and the FMF a minimum of 12.[45] Former WPS teams Western New York Flash, Boston Breakers, Chicago Red Stars, and Sky Blue FC were joined by four other teams, for a total of eight teams for the inaugural season in 2012. Each club is allowed a minimum of 18 players on their roster, with a maximum of 20 players allowed at any time during the season.[46] Each team's roster includes up the three allocated USWNT players, two Mexico women's national team players, and two CANWNT players via the NWSL Player Allocation. Each team also has, as of 2015, four spots for international players. The remaining roster spots must be filled by domestic players from the United States.

In 2013, the Houston Dynamo of MLS stated interest in starting a women's team. By December 2013, the NWSL approved the new team, the Houston Dash, run by the Dynamo organization, for expansion in 2014.[47] After the media boom of the 2015 FIFA Women's World Cup, MLS side Orlando City SC showed interest in starting a women's team for the 2016 season. On October 20, 2015, it was announced Orlando City would launch its new NWSL team, the Orlando Pride, in the 2016 season.[48]

The NWSL in the first professional women's league to reach nine teams with the addition of the Houston Dash and is the first to last past its third season.

Folding of the W-League and Creation of United Women's Soccer

The W-League had served as a Division II development organization and league for women's soccer in the United States for 21 seasons. However, the W-League announced on November 6, 2015 that the league would cease operation ahead of the 2016 season.[49] In response to the folding of the W-League and the problems occurring in the WPSL, the other Division II league in America, United Women's Soccer (UWS) was founded as a planned second-division pro-am women's soccer league in the United States. There are currently eight known teams, with plans to create the league with two conferences for the 2016 inaugural season.[50]

1980s

Mike Ryan was named the first national team coach after his success with the Tacoma Cozars, who won three straight national titles. A national women's soccer team was selected in 1982, 1983, and 1984, but they never played together. In 1985, about 70 women, mostly players from university teams, were invited to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, to participate in the Olympic Sports Festival. At the end of the festival, Mike Ryan selected 17 players to play in a tournament in Italy. The players practiced for three days at the C.W. Post campus of Long Island University. They were issued men's practice uniforms and sewed the "USA" decal on the front of their shirts the night before they flew to Italy.[51]

The national team's matches against Italy were brutal and many criticized Ryan on his coaching ability. After the Italy trip, he was unceremoniously removed as national team coach and replaced by Anson Dorrance, who had begun to build the most successful collegiate women's program in history at North Carolina.[51][52] Dorrance built a national team with a core of young players and put the team in a 3–4–3 system, now legendary, but then scandalous.[53] Dorrance had been told that if the team did not perform, he would be removed as head coach. This put a lot of pressure on the team to do well. The team played for no money, got around with third-class travel and cheap motels, and had little food. The attendance at their matches was low all throughout the 1980s.[54]

In 1988, FIFA hosted an invitational in China to test to see if a women's World Cup was feasible. The U.S. women's national team took part in the tournament and while they made it past the group stage, they were beaten by Norway in the quarter-finals.[55]

1991 Women's World Cup

The U.S. team took part in the first CONCACAF Women's Championship in 1991, which determined CONCACAF's single qualifier for the 1991 Women's World Cup. It took place between April 18 and 27, 1991 in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. The U.S. won all of its group matches in the tournament as well as all matches in the knockout stage, qualifying to the 1991 World Cup.

In 1991, FIFA held the first FIFA Women's World Cup in China with 12 teams participating. The U.S. team consisted of now USWNT legends, including Joy Fawcett, Shannon Higgins, Kristine Lilly, Julie Foudy, Michelle Akers, Mia Hamm, April Heinrichs, Carla Overbeck and Carin Jennings. The United States won all six of its games and outscored its opponents 25–5.[53] The team won its three group matches to finish first in the group, beat Taipei in the quarter-finals, and defeated Germany 5–2 in the semifinals. The United States beat Norway 2–1 in the final, and was the first U.S soccer team to win a World Cup.

The team expected great fanfare upon returning to the United States, having just won the first Women's World Cup. Unfortunately, this was not the case. The win did not draw national attention and the team was without money. There was no training or games, and many players returned to college to await the fate of the team.[54] It was nine months after the World Cup that the team played another match; however, they only played in two matches in 1992.[56]

1993–1994

The team seemed to rebound in 1993, playing in significantly more matches than the previous year. Attendance had also increased from the previous year. The U.S. team took part in the 1993 CONCACAF Women's Championship in Long Island, New York, winning all of the matches they played.[57]

In 1994, the main task for the women's national team was to qualify for the 1995 Women's World Cup. In preparation for the qualifying tournament, the team competed in the inaugural edition of the Algarve Cup in Portugal. The U.S. finished in top position in its group; however, they lost to Norway in the final that was a replay of the 1991 Women's World Cup Final. The Algarve Cup was followed by wins over Trinidad & Tobago and Canada. The U.S. team then competed in the inaugural USA Women's Cup, pitting the U.S. against Germany, China, and Norway, their biggest rival at the time. They won all three matches, including a 4–1 win over Norway, to take the USA Women's Cup 1994.[58]

The 1994 CONCACAF Women's Championship in August determined the CONCACAF's two qualifiers for the 1995 FIFA Women's World Cup. The team easily won the tournament to qualify for their second World Cup.[59]

1995

The women's national team spent the first part of 1995 preparing for the World Cup. The team once again competed in the Algarve Cup in Portugal, during March. They started off the tournament well; however, a loss to Denmark put them in the third place match against Norway. The U.S. lost in penalty kicks. Next up was the Tournoi International Feminin in France in April. The team was back in shape, winning all of their matches, including a 3–0 win against host France.[60]

The team spent the two months leading up to the World Cup practicing, playing in six friendlies, all victories. They competed against Finland (2–0 and 6–0), Brazil (3–0 and 4–1), and Canada (9–1 and 2–1) just two weeks before the 1995 World Cup.[61]

In the 1995 FIFA Women's World Cup in June, the United States won their group with 2 wins against Denmark and Australia and a draw against China. During their match against Denmark, goalkeeper Brianna Scurry received a red card for handling outside the penalty area and faced a two-game suspension.[62] Since the US had already used their three substitutions, they had to finish the game with Mia Hamm in goal. In the quarterfinals, the U.S. faced Japan and won 4–0. Unfortunately, the quarter-final win led to a dreaded match against Norway. Michelle Akers, who was injured earlier in the tournament, returned at less than full strength. They lost the match 0–1 and had to settle for third place, beating China 2–0. The result was disappointing given that the U.S. had been the favorite to win.[63]

Shortly after their disappointing World Cup run, the U.S. competed in the 1995 USA Women's Cup in July and August in New Britain, CT. The U.S. team won all of the matches that they played in the tournament, including a 2–1 win over the 1995 World Cup Champion, Norway, to take the cup.[64]

1996

The women's national team entered the Brazil Soccer Cup in January 1996 and won all four matches they played. The championship game was against Brazil and resulted in a draw, but the U.S. prevailed in penalty kicks.[65] Following the Brazil Cup, the U.S. began their preparation for the Olympics, the first time women's soccer would ever be played at the event. They began their preparation with a series of friendlies, including two matches against Norway that resulted in one win and one loss.[56] The U.S. team once again competed in the USA Women's Cup in May, winning all of the matches they played in the tournament.

Leading up to the 1996 Olympics, a dispute between the players at the United States Soccer Federation (USSF) put their Olympic dreams in jeopardy. At this time, the members of the U.S. women's national team received $1,000 a month. However, they wanted to receive bonuses for any medal won, like the men's team; USSF was only offering a bonus if the team won gold. Several star players boycotted the training camp in January because of the dispute.[66] It was eventually settled and the players returned in order to make the Olympic roster.[54]

At the 1996 Olympics in Atlanta, women's soccer was added for the first time.[67] In the group stage of the tournament, the U.S. came away with two wins against Denmark and Sweden and a draw against China. In the semi-finals, the U.S. faced their long-time rival, Norway. While they fell behind in the first half, they were able to tie the game with a penalty shot late in the second half. During extra time, the U.S. scored, beating Norway to move on to the final. The U.S. team went against China in the Olympic final and won 2–1, taking away the gold medal.[68] By the time the games were over, the top thirteen crowds in U.S. history for women's soccer had been set, including 76,489 for the final. However, the final match was not broadcast on national television.

Following the 1996 Olympics, women's soccer began to attract serious attention around the nation. One player especially, Mia Hamm, became the face of women's soccer.

1997–1998

The U.S. women's national team played 18 games in 1997, mostly international friendlies. The only major tournament was the 1997 USA Women's Cup held in May, which the U.S. once again won. The team ended the season with 16 wins and 2 losses.[69]

The team started off 1998 with the Guangzhou International Tournament in China with two wins against Sweden and Norway and a draw against China. They participated in the 1998 Algarve Cup in March and started off well with two wins in the group stage, but lost to Norway, leading to third place. A series of friendlies followed the Algarve until July, when women's soccer was added to the Goodwill Games for the first time. Only four teams competed and the U.S. took the gold, beating Denmark 5–0 and China 2–0. They ended off the year with the 1998 USA Women's Cup, winning every match they played. It was during that tournament that Mia Hamm scored her 100th goal.[70]

1999: The Road to Pasadena

In preparation for the 1999 FIFA Women's World Cup, the U.S. women's national team played nineteen games, entitled "The Road to Pasadena," leading up to the World Cup. The team started off the year with two friendlies against Portugal in January, winning both. In February, they got a wake up call when they lost an exhibition match against the FIFA World Stars. In March, they competed in the 1999 Algarve Cup, and lost in the final to China, 1–2. Following the devastating losses, the team spent the next three months with a series of friendlies in preparation for the World Cup. Their only loss was against China in late April.[57]

1999 World Cup

The Women's World Cup was held in the United States for the first time in 1999. Originally, FIFA had planned a small, low-key event, as the other two cups were. The USSF proposed that this World Cup was an opportunity to promote soccer in the United States and called for the use of larger stadiums across the nation. FIFA eventually allowed the competition to be staged at the level that the USSF wanted.[71]

The United States' roster for the World Cup was filled with veterans, six of the players having been in both the 1991 World Cup and the 1995 World Cup. Michelle Akers was on the original national team in 1985, Mia Hamm had just set the world scoring record, and Kristine Lilly was the world's leader in international appearances. In addition to the six players that appeared in the first two World Cups, six players would be playing their second World Cup, and eight players were appearing in a World Cup for the first time. Additionally, the team included thirteen of the sixteen members of the 1996 Olympic Team.[72]

During the group stage, the United States won all three of its matches, beating Denmark 3–0, Nigeria 7–1, and North Korea 3–0.[56] Their opening game against Denmark brought a crowd of 78,972 fans, setting a world record for attendance at any women's sporting even, and an all-time Giants Stadium record for a sporting event of any kind.[71]

In the quarter-finals, the United States went against Germany in perhaps their toughest game of the tournament. They did pull through and beat Germany 3–2. In the semi-finals, the United States went against Brazil, winning easily 2–0 and advancing to the final against China. The final was held at the Rose Bowl in Pasadena and brought in over 90,000 fans. The game was scoreless after 90 minutes and two overtime periods, resulting in a penalty kick shootout. Briana Scurry, having proved herself throughout the entire tournament, saved the third shot by Liu Yang, putting the United States ahead. Brandi Chastain, a veteran on the team, scored the last shot, giving the U.S. the victory.[71]

Following the World Cup victory in July, the US took almost two months off to rest before playing a friendly against Ireland in September in Foxboro, MA. They then played Brazil in October, winning again. The United States also once again took part in the USA Women's Cup in 1999, winning all of the matches they played. Every game after the World Cup brought in large crowds, highlighted by 35,000 for the final two USA Women's Cup games.[71]

After their performance at the World Cup, the team made a 12-city Victory Tour playing exhibition indoor matches against a team of international stars. The tour lasted three months and featured cities that had not seen MLS or national team action.[73]

2000 Strike and Summer Olympics

In December 1999, the team announced they would be sitting out the 2000 Australia Cup over a contract dispute with US Soccer.[74][75] The federation was forced to send a team of younger players in place of the group that had competed at the World Cup the previous summer. Following the tournament, this younger group sided with the veterans and also refused to play until a more favorable contract was signed. The dispute was resolved in late January, and US Soccer was forced to increase the players' salaries, to a minimum of $5,000 a month.[76] This raised the women's team salaries to be more on par with the men's team and reflected growth of the team.[77]

Following the dispute and the Australia Cup, the team had a year packed with major tournaments leading up to the Olympics. They won their first Algarve Cup in March, taking Portugal in an impressive 7–0 in the opening match of the tournament. The USA Women's Cup was played in May and the team had two shutouts to win the tournament. During the tournament, Kristine Lilly became the first player to earn a 200th cap in international play. The Pacific Cup took place in late May and although they suffered a loss in their first match against China, they recovered and won the tournament.[77]

In late June, the national team won the inaugural Women's Gold Cup, which served as the CONCACAF Women's Championship. In their last major tournament before the Olympics, the team headed to Germany for the DFB 100th Anniversary Tournament, which they easily won. Following a "Road to Sydney" friendly series, the team headed to Australia for the third time that year.[77]

Having won gold in 1996, the team automatically qualified for the Olympics. They were placed in a group with Norway, China, and Nigeria, guaranteeing a tough group stage. They made it through to the knockout stage and ended up in the final against Norway. At the end of the 90 minutes, the score was tied 2–2 after intense play. The final goal of the game was considered controversial. In overtime, United States defender Joy Fawcett attempted to clear an incoming ball. Instead, it hit Norwegian player Dagny Mellgren in the arm and she then kicked it into goal. The goal was allowed, and Norway won the game and the gold medal. The United States had to settle for silver.[77][78]

The women's national team saw a number of changes in 2000, with several veteran players retiring or injured, allowing the younger generation to step up.

See also

- American Cup

- American Football Association

- American Soccer League (disambiguation)

- Soccer in Houston

- Soccer in Los Angeles

- Soccer in New York City

- History of professional soccer in Seattle

- History of the U.S. Open Cup

- List of American and Canadian soccer champions

- Major League Soccer

- North American Soccer League (1968–1984)

- North American Soccer League (2011–)

- Pasuckuakohowog, a Native American form of a "football" sport (to 17th century)

- Soccer in the United States

- United Soccer Leagues

- U.S. Soccer Federation

- United States soccer league system

- United States men's national soccer team

- United States women's national soccer team

- U.S. Open Cup

Notes

- In fact, the ball that was used in the match is kept at the National Soccer Hall of Fame.[2]:22

References

- Crawford, Scott (2013). A History of Soccer in Louisiana: 1858–2013. New Orleans: LAprepSoccer Publishing Co. ISBN 1489521887.

- Wangerin, David (2008). Soccer in a football world : the story of America's forgotten game. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Bundgaard, Axel (July 11, 2005). Muscle and Manliness: The Rise of Sport in American Boarding Schools. Syracuse University Press. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-8156-3082-1.

- "Allaway, Roger West Hudson: A Cradle of American Soccer". Archived from the original on May 25, 2009. Retrieved June 10, 2011.

- Cochrane, Ernest Cecil; Burchell, Henry Philip; Orton, George W.; Cahill, Thomas W. (1910). Spalding's Official "soccer" Football Guide. New York: American Sports Publishing Company.

- Litterer, Dave. "The Year in American Soccer – 1929". The American Soccer Archives. Archived from the original on July 13, 2013. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

- Westervelt, Ted (October 5, 2010). "Doing the Same Thing Over and Over and Expecting Different Results". Soccerreform.us. Archived from the original on May 28, 2011. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

- "1928 National Challenge Cup Results". TheCup.us. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

- Allaway, Roger (October 24, 2010). "What was the "Soccer War"?". BigSoccer. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

- September 25, 1928 The Globe

- November 4, 1929 The Globe

- Litterer, Dave. "The Year in American Soccer – 1930". The American Soccer Archives. Archived from the original on May 10, 2013. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

- Litterer, Dave. "The Year in American Soccer – 1933". The American Soccer Archives. Archived from the original on November 2, 2015. Retrieved June 5, 2011.

- by who?

- "FIFA: USA – Paraguay match report". FIFA. Retrieved June 9, 2006.

- "CNN/Sports Illustrated – Bert Patenaude". CNN. Retrieved June 9, 2006.

- "Planet World Cup – World Cup Trivia". PlanetWorldCup.com. Retrieved June 9, 2006.

- "The Football Association 20 World Cup Facts". The FA. Archived from the original on February 1, 2009. Retrieved June 9, 2006.

- "FIFA World Cup hat-tricks" (PDF). FIFA. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 19, 2006. Retrieved November 10, 2006.

- "1930 FIFA World Cup Uruguay – Awards". Fifa.com. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- Yannis, Alex (April 22, 1985). "U.S. Soccer Team Hindered". The New York Times. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- "CNNSI.com – Inside Game – Michael Lewis – Offside Remarks – CNNSI.com's Lewis: Learning from history – Friday November 10, 2000 07:29 PM". Sportsillustrated.cnn.com. Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- "U.S. defeats Mexico again in Gold Cup final". MSNBC. Archived from the original on June 26, 2007. Retrieved June 30, 2007.

- "South American soccer federation miffed at U.S." ESPNsoccernet. July 4, 2007. Retrieved July 4, 2007.

- Krishnaiyer, Kartik (August 15, 2008). "Bob Bradley's US Squad Stale and Predictable". Major League Soccer Talk.

- "Egypt 3–0 USA". BBC Sport. June 21, 2009. Retrieved June 30, 2009.

- Chowdhury, Saj (June 25, 2009). "Spain 2–0 United States". BBC Sport. Retrieved June 30, 2009.

- United States 3–2 Brazil – BBC Sport

- "USA Gold Cup Roster". The Washington Post.

- "WUSA Granted U.S. Soccer Membership as Division I Women's Professional Soccer League". www.ussoccer.com. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "Cash-strapped WUSA folds after 3 seasons". Arizona Daily Sun. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "WSII". wsii.typepad.com. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "SOCCER.COM || WUSA – Women's United Soccer Association". www.soccer.com. Archived from the original on August 21, 2004. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "U.S. Women's Pro League Prepares to Blast Back Onto Soccer Scene | Fox News". Fox News. June 28, 2006. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "Relaunch of WUSA set for spring 2008". ESPNFC.com. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "Women's pro soccer team put on hold – St. Louis Business Journal". St. Louis Business Journal. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "New League To Launch As Women's Professional Soccer". US Soccer Players. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "Womens' Professional Soccer Takes Grassroots Approach to Growth – Athletic Business". www.athleticbusiness.com. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "WPS Enjoys a Major World Cup Bump: Attendance is Up in All Markets | Sports Then and Now". Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- Hock, Lindsay (January 31, 2012). "Women's Professional Soccer suspends 2012 season amid legal dispute with former owner". The She Network.

- "WPS Suspends 2012 Season | The Women's Game". thewomensgame.com. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "Women's Professional Soccer League Folds". The Huffington Post. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "Semi-pro WPSL to offer new women's pro league". Sporting News. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "Equalizer Soccer – New women's soccer league in the works for 2013 following meeting in Chicago". Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "Equalizer Soccer – Eight teams to start new women's pro soccer league in 2013". Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "2015 Roster Rules – National Women's Soccer League". www.nwslsoccer.com. Archived from the original on December 31, 2015. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "Houston Dash Officially Announced for NWSL 2014". Dynamo Theory. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "Orlando Pride women's soccer team to join NWSL in 2016". www.baynews9.com. Archived from the original on October 25, 2015. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "Equalizer Soccer – USL W-League, once top flight, folds after 21 seasons". Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- "SoccerAmerica – New women's league plans to launch 12/22/2015". www.socceramerica.com. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- Griendling, Bob (November 6, 2000). "The 17 women who blazed an amazing trail" (PDF). U.S. Soccer.

- "When the U.S. Women's National Team was made in Washington". Society for American Soccer History. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "The Continual Rise of the USWNT". Bleacher Report. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- Dare to Dream: The Story of the U.S. Women's Football Team. By Ouisie Shapiro. HBO Sports, 2007. DVD.

- "Women's FIFA Invitational Tournament 1988". www.rsssf.com. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "USA Women's National Team: All-time Results, 1985–present". homepages.sover.net. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "USA Women's National Team: All-time Results, 1985–present". homepages.sover.net. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "The Year in American Soccer, 1994". homepages.sover.net. Archived from the original on May 4, 2010. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "The Year in American Soccer, 1994". homepages.sover.net. Archived from the original on May 4, 2010. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "The Year in American Soccer, 1995". homepages.sover.net. Archived from the original on September 26, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "The Year in American Soccer, 1995". homepages.sover.net. Archived from the original on September 26, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- JONES, GRAHAME L. (June 9, 1995). "U.S. Wins but Protests Red Card : Women's soccer: Controversial call against American goalkeeper mars 2–0 victory over Denmark". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "The Year in American Soccer, 1995". homepages.sover.net. Archived from the original on September 26, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "The Year in American Soccer, 1995". homepages.sover.net. Archived from the original on September 26, 2018. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "The Year in American Soccer, 1996". homepages.sover.net. Archived from the original on August 15, 2017. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- JONES, GRAHAME L. (December 6, 1995). "Women Soccer Players Boycott Olympic Camp : Atlanta Games: Dispute involving top U.S. players hinges on rejection of contract offers". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "Amazing Moments in Olympic History- 1996 Women-s Soccer Team". Team USA. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "The Year in American Soccer, 1996". homepages.sover.net. Archived from the original on August 15, 2017. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "The Year in American Soccer, 1997". homepages.sover.net. Archived from the original on December 18, 2010. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "The Year in American Soccer, 1998". homepages.sover.net. Archived from the original on November 5, 2015. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- "The Year in American Soccer, 1999". homepages.sover.net. Archived from the original on January 3, 2017. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- "DiCicco Announces 1999 U.S. Women's World Cup Team; Six Players will Appear in their Third World Cup Tournament". www.ussoccer.com. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- "Soccer Americana: USWNT 1999 Victory Tour". Soccer Americana. December 24, 2014. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- "Women's Team in Contract Feud". LA Times. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- "Women's Soccer Team Won't Go to Australia". New York Times. Retrieved April 1, 2016.

- "SOCCER; New Deal Gives Women Parity in Pay and Full Time Status". New York Times. Retrieved April 3, 2016.

- "The Year in American Soccer, 2000". homepages.sover.net. Archived from the original on December 29, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2016.

- "Olympic Football Tournaments Sydney 2000 – Women". FIFA. Retrieved April 3, 2016.