History of the Dominican Republic

The recorded history of the Dominican Republic began when the Genoa-born navigator Christopher Columbus, working for the Spanish Crown, happened upon a large island in the region of the western Atlantic Ocean that later came to be known as the Caribbean. It was inhabited by the Taíno, an Arawakan people, who variously called their island Ayiti, Bohio, or Quisqueya (Kiskeya). Columbus promptly claimed the island for the Spanish Crown, naming it La Isla Española ("the Spanish Island"), later Latinized to Hispaniola. What would become the Dominican Republic was the Spanish Captaincy General of Santo Domingo until 1821, except for a time as a French colony from 1795 to 1809. It was then part of a unified Hispaniola with Haiti from 1822 until 1844. In 1844, Dominican independence was proclaimed and the republic, which was often known as Santo Domingo until the early 20th century, maintained its independence except for a short Spanish occupation from 1861 to 1865 and occupation by the United States from 1916 to 1924.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the Dominican Republic |

|

| Pre-Spanish Hispaniola (-1492) |

| Captaincy General of Santo Domingo (1492-1795) |

| French Santo Domingo (1795–1809) |

| España Boba (1809-1821) |

| Republic of Spanish Haiti (1821-1822) |

| Republic of Haiti (1822-1844) |

| First Republic (1844-1861) |

|

|

| Spanish occupation (1861-1865) |

| Second Republic (1865-1916) |

| United States occupation (1916-1924) |

| Third Republic (1924-1965) |

| Fourth Republic (1966-) |

| Topics |

|

Military history Postal history Jewish history |

|

|

Pre-Spanish history

The Taíno people called the island Quisqueya (mother of all lands) and Ayiti (land of high mountains). At the time of Columbus' arrival in 1492, the island's territory consisted of five chiefdoms: Marién, Maguá, Maguana, Jaragua, and Higüey. These were ruled respectively by caciques Guacanagarix, Guarionex, Caonabo, Bohechío, and Cayacoa.

Spanish colony: 1492–1795

Arrival of the Spanish

Christopher Columbus reached the island of Hispañola on his first voyage, in December 1492. On Columbus' second voyage in 1493, the colony of La Isabela was built on the northeast shore. Isabela nearly failed because of hunger and disease. In 1496 Santo Domingo was built and became the new capital. Here the New World's first cathedral was erected, and for a few decades, Santo Domingo was also the administrative heart of the expanding empire. Before they embarked on their prosperous endeavors, men like Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro lived and worked in Santo Domingo.

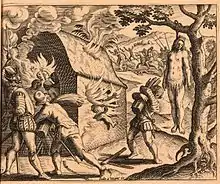

Caonabo, the cacique, (leader or chief), of Maguana, one of five Taino geographical divisions on Hispaniola, attacked Columbus on January 13, 1493. Shooting arrows and wounding a few Spaniards, the Tainos halted the invaders' collection of provisions for Columbus's return trip to Spain. Caonabo struck again when his forces attacked and burned a fort built by Columbus, killing forty Spaniards. During the last trip of Christopher Columbus, in 1495, the Taino leader Guarionex, supported by Caonabo and other Taino leaders, staged the Battle of La Vega Real against the Spanish in 1495. But while more than ten thousand Tainos fought against the Spanish, they succumbed to the power of the Spanish weaponry.

When Guarionex attacked the Spanish again, in 1497, both he and Caonabo were caught by the Spanish and both shipped to Spain; on the journey Caonabo died—according to legend, of rage—and Guarionex drowned. His wife, Anacaona, moved to the Xaragua division, where her brother, Bohechio, was cacique. After Bohechio's death, she became cacique and subsequently extended refuge and assistance to runaway enslaved Tainos and Africans.

One hundred thousand Tainos died from 1494–1496, half of them by their own hand through self-starvation, poison, leaps from cliffs, etc.[1] The conquistador-turned-priest Bartolomé de las Casas wrote an eyewitness history of the Spanish incursion into the island of Hispaniola that reported the conquistadors' almost feral misconduct:

Into this land of meek outcasts there came some Spaniards who immediately behaved like ravening wild beasts, wolves, tigers or lions that had been starved for many days. And Spaniards have behaved in no other way during the past forty years, down to the present time, for they are still acting like ravening beasts, killing, terrorizing, afflicting, torturing, and destroying the native peoples, doing all this with the strangest and most varied new methods of cruelty.

Sixteenth century

Hundreds of thousands of Tainos living on the island were enslaved to work in gold mines. As a consequence of disease, forced labor, famine, and mass killings, by 1508, only 60,000 were still alive.[2] In 1501, the Spanish monarchs, Ferdinand I and Isabella, first granted permission to the colonists of the Caribbean to import African slaves, who began arriving to the island in 1503. The first enslaved blacks were purchased in Lisbon, Portugal. Some had been transported there from the West African Guinea coast, and others had been born and raised in Portugal or Spain. Southern Spain and Portugal were multiethnic and multiracial regions long before the “discovery” of the New World, and many Africans, free and enslaved, participated in the Iberian Peninsula's conquest and colonization of the Americas.[3]

In 1510, the first sizable shipment, consisting of 250 Black Ladinos, arrived in Hispaniola from Spain. Eight years later African-born slaves arrived in the West Indies. Many of the Africans brutally jammed into the slave ships had been the losers in Africa's endemic and endless wars. Others were kidnapped from the coast or taken from villages inland.[4] The Colony of Santo Domingo was organized as the Royal Audiencia of Santo Domingo in 1511. Sugar cane was introduced to Hispaniola from the Canary Islands, and the first sugar mill in the New World was established in 1516, on Hispaniola.[5] The need for a labor force to meet the growing demands of sugar cane cultivation led to an exponential increase in the importation of slaves over the following two decades. The sugar mill owners soon formed a new colonial elite and convinced the Spanish king to allow them to elect the members of the Real Audiencia from their ranks. Poorer colonists subsisted by hunting the herds of wild cattle that roamed throughout the island and selling their hides. The enslaved population numbered between twenty and thirty thousand in the mid-sixteenth century and included mine, plantation, cattle ranch, and domestic laborers. A small Spanish ruling class of about twelve hundred monopolized political and economic power, and it used ordenanzas (laws) and violence to control the population of color.

In 1517, a guerrilla war between the colonizers and Taino and African forces was initiated by the Taino leader Enriquillo. Descending from the Bahoruco Mountains with his troops, Enriquillo killed Spaniards, devastated farms and property, and took Africans back with him. The crown appointed General Francisco Barrionuevo, a veteran of many battles in Spain, as captain to lead the war against Enriquillo. Barrionuevo opted to negotiate, realizing that violence had not worked and that resources for more armed actions were scarce. In 1533 he met Enriquillo on what is today's Cabrito Island, in the middle of Lake Jaragua (now Enriquillo Lake) and reached a peace agreement that granted Enriquillo and his troops freedom and land.

The first known armed rebellion of enslaved Africans occurred in 1521. On Christmas Eve two hundred enslaved workers fled the plantation of Diego Columbus, located on the Isabela River near Santo Domingo, and headed south toward Azua. Others from plantations in Nigua, San Cristóbal, and Baní joined them on the march, burning plantations and killing several Spaniards. According to official records, they stopped next at the Ocoa plantation, with the intention of killing more whites and recruiting more enslaved blacks and Indians, then moved on to Azua. After being informed of the insurrection, Columbus recruited a small army, which, mounted on horseback and shouting their battle cry "Santiago", headed south in pursuit.[6] In the meantime, the rebels entered the plantation of Melchor de Castro near the Nizao River where they killed one Spaniard, sacked the house, and freed more enslaved persons, including Indians. Columbus's army confronted the rebels at the Nizao, the Spanish shooting at them with guns and the rebels responding by throwing stones and logs. Five days later the Spanish attacked again. They caught several rebels, whom they executed by lynching along the colonial road, but many more had escaped to face later attacks, in which more were killed or apprehended.

By the mid-sixteenth century, there were an estimated seven thousand maroons (runaway slaves) beyond Spanish control on Hispaniola. The Bahoruco Mountains were their main area of concentration, although Africans had escaped to other areas of the island as well. From their refuges, they descended to attack the Spanish. In 1546 the slave Diego de Guzman led an insurrection that swept through the San Juan de la Maguana area, after which he escaped to the Bahoruco Mountains. After his capture, de Guzman was savagely killed and some of his fellow rebels were burned alive, others burned with branding irons, others hung, and others had their feet cut off. The most extended insurrection was led by Sebastián Lemba. For fifteen years Lemba attacked Spanish towns, plantations, and farms with an army of four hundred Africans. Lemba was eventually caught and was executed in 1548. His head was mounted on the door that connected the Fort of San Gil (today Fort Ozama) to Fort Conde, and for centuries it was called "the Lemba door". Insurrections continued to burden the colony's tranquility and economy. From 1548 to the end of the sixteenth century, maroons attacked farms, plantations, and villages. By 1560 the colony was unable to recruit and pay troops to pursue the rebels.

While sugar cane dramatically increased Spain's earnings on the island, large numbers of the newly imported slaves fled into the nearly impassable mountain ranges in the island's interior, joining the growing communities of cimarrónes—literally, 'wild animals'. By the 1530s, cimarrón bands had become so numerous that in rural areas the Spaniards could only safely travel outside their plantations in large armed groups. Beginning in the 1520s, the Caribbean Sea was raided by increasingly numerous French pirates. In 1541 Spain authorized the construction of Santo Domingo's fortified wall, and in 1560 decided to restrict sea travel to enormous, well-armed convoys. In another move, which would destroy Hispaniola's sugar industry, in 1561 Havana, more strategically located in relation to the Gulf Stream, was selected as the designated stopping point for the merchant flotas, which had a royal monopoly on commerce with the Americas. In 1564, the island's main inland cities Santiago de los Caballeros and Concepción de la Vega were destroyed by an earthquake. In the 1560s English pirates joined the French in regularly raiding Spanish shipping in the Americas.

With the conquest of the American mainland, Hispaniola quickly declined. Most Spanish colonists left for the silver-mines of Mexico and Peru, while new immigrants from Spain bypassed the island. Agriculture dwindled, new imports of slaves ceased, and white colonists, free blacks, and slaves alike lived in poverty, weakening the racial hierarchy and aiding intermixing, resulting in a population of predominantly mixed Spaniard, African, and Taíno descent. Except for the city of Santo Domingo, which managed to maintain some legal exports, Dominican ports were forced to rely on contraband trade, which, along with livestock, became the sole source of livelihood for the island dwellers.

In 1586, Sir Francis Drake captured the city of Santo Domingo, collecting a ransom for its return to Spanish rule. A third of the city lay in ruins and almost all of its civic, military and religious buildings had been either damaged or destroyed. During his occupation of Santo Domingo, Drake sent a black boy with a message to the governor. A Hidalgo who was standing by considered this an insult and ran the boy through with his sword.[7] The English commander, infuriated, proceeded to the spot where the murder had been committed and had two friars hanged. He told the governor that he would hang two more friars every day until the murderer had been executed. The murderer was hanged by his own countrymen.

In 1592, Christopher Newport attacked the town of Azua on the bay of Ocoa, which was taken and plundered.[8] In 1595 the Spanish, frustrated by the twenty-year rebellion of their Dutch subjects, closed their home ports to rebel shipping from the Netherlands cutting them off from the critical salt supplies necessary for their herring industry. The Dutch responded by sourcing new salt supplies from Spanish America where colonists were more than happy to trade. So large numbers of Dutch traders/pirates joined their English and French brethren on the Spanish main.

Seventeenth century

In 1605, Spain was infuriated that Spanish settlements on the northern and western coasts of the island were carrying out large scale and illegal trade with the Dutch, who were at that time fighting a war of independence against Spain in Europe, and the English, a very recent enemy state, and so decided to forcibly resettle their inhabitants closer to the city of Santo Domingo.[9] This action, known as the Devastaciones de Osorio, proved disastrous; more than half of the resettled colonists died of starvation or disease, over 100,000 cattle were abandoned, and many slaves escaped.[10] Five of the existing thirteen settlements on the island were brutally razed by Spanish troops – many of the inhabitants fought, escaped to the jungle, or fled to the safety of passing Dutch ships. The settlements of La Yaguana, and Bayaja, on the west and north coasts respectively of modern-day Haiti were burned, as were the settlements of Monte Cristi and Puerto Plata on the north coast and San Juan de la Maguana in the southwestern area of the modern-day Dominican Republic.

The withdrawal of the colonial government from the northern coastal region opened the way for French buccaneers, who had a base on Tortuga Island, off the northwest coast of present-day Haiti, to settle on Hispaniola in the mid-seventeenth century. Although the Spanish destroyed the buccaneers' settlements several times, the determined French would not be deterred or expelled. The creation of the French West India Company in 1664 signalled France's intention to colonize western Hispaniola. Intermittent warfare went on between French and Spanish settlers over the next three decades; however, Spain, hard-pressed by warfare in Europe, could not maintain a garrison in Santo Domingo sufficient to secure the entire island against encroachment. In 1697, under the Treaty of Ryswick, Spain ceded the western third of the island to France.

In 1655, Oliver Cromwell dispatched a fleet, commanded by Admiral Sir William Penn, to conquer Santo Domingo. A Spanish defending force of perhaps 400–600 men, mostly militia, repulsed a landing force of 9,000 men.[11] Yet although the English had failed to overrun the island, they nevertheless seized nearby Jamaica, and other foreign strongholds subsequently began multiplying throughout the West Indies. Madrid sought to contest such encroachments by using Santo Domingo as an advance military base, but Spanish power was by now too depleted to expel the rival colonies. The city itself was furthermore subjected to a smallpox epidemic, cacao blight, and hurricane in 1666; another storm two years later; a second epidemic in 1669; a third hurricane in September 1672; plus an earthquake in May 1673 that killed two dozen residents.[12]

During this seventeenth "century of misery", the Spanish on Hispaniola continued to persecute maroons living peacefully in the island's interior mountains and valleys. With little to show for it, this policy of armed harassment added more public expense to a weak colonial economy, and the financial recovery of the Spanish colony in the eighteenth century led to increased slave insurrections and marronage.

Eighteenth century

The House of Bourbon replaced the House of Habsburg in Spain in 1700 and introduced economic reforms that gradually began to revive trade in Santo Domingo. The crown progressively relaxed the rigid controls and restrictions on commerce between Spain and the colonies and among the colonies. The last flotas sailed in 1737; the monopoly port system was abolished shortly thereafter. By the middle of the century, the population was bolstered by emigration from the Canary Islands, resettling the northern part of the colony and planting tobacco in the Cibao Valley, and importation of slaves was renewed. The population of Santo Domingo grew from about 6,000 in 1737 to approximately 125,000 in 1790. Of this number, about 40,000 were white landowners, about 25,000 were mulatto freedmen, and some 60,000 were slaves. However, it remained poor and neglected, particularly in contrast with its western, French neighbor Saint-Domingue, which became the wealthiest colony in the New World and had half a million inhabitants.[13] The 'Spanish' settlers, whose blood by now was mixed with that of Tainos, Africans and Canary Guanches, said to themselves: "It does not matter if the French are richer than us, we are still the true inheritors of this island. In our veins runs the blood of the heroic conquistadores who won this island of ours with sword and blood."[14]

When the War of Jenkins' Ear between Spain and Britain broke out in 1739, Spanish privateers, particularly from Santo Domingo, began to troll the Caribbean Sea, a development that lasted until the end of the eighteenth century. During this period, Spanish privateers from Santo Domingo sailed into enemy ports looking for ships to plunder, thus harming commerce with Britain and New York. As a result, the Spanish obtained stolen merchandise—foodstuffs, ships, enslaved persons—that were sold in Hispaniola's ports, with profits accruing to individual sea raiders. These practices of human traffic and terror facilitated capital accumulation. The revenue acquired in these acts of piracy was invested in the economic expansion of the colony and led to repopulation from Europe.[15]

Dominicans constituted one of the many diverse units which fought alongside Spanish forces under Bernardo de Gálvez during the conquest of British West Florida (1779–1781).[16][17]

As restrictions on colonial trade were relaxed, the colonial elites of St. Domingue offered the principal market for Santo Domingo's exports of beef, hides, mahogany, and tobacco. With the outbreak of the Haitian Revolution in 1791, the rich urban families linked to the colonial bureaucracy fled the island, while most of the rural hateros (cattle ranchers) remained, even though they lost their principal market. Although the population of Spanish Santo Domingo was perhaps one-fourth that of French Saint-Domingue, this did not prevent the Spanish king from launching an invasion of the French side of the island in 1793, attempting to take advantage of the chaos sparked by the French Revolution.[18] French forces checked Spanish progress toward Port-au-Prince in the south, but the Spanish pushed rapidly through the north, most of which they occupied by 1794.

Although the Spanish military effort went well on Hispaniola, it did not so in Europe. The Spanish colony was ceded first to France in 1795 as part of the Treaty of Basel between the defeated Spanish and the French, then it was invaded by the British in 1796.[2] Five years later, black slaves in rebellion invaded from Saint-Domingue. The devastated Spanish-speaking colony was then occupied by the French in 1802, in spite of the dramatic defeat of Napoleon's forces at the hands of the former French slaves who proclaimed the independent Republic of Haiti in 1804. Santo Domingo was invaded again by Haitians in 1805 and then yet again by the British in 1809.[2] The Spanish reclaimed it later that year but found the colony in economic ruins and demographic decline.[2]

Spanish colony: 1809–1821

The population of the new Spanish colony stood at approximately 104,000. Of this number, about 30,000 were slaves, and the rest a mixture of white, Indian, and black. The European Spaniards were few, and consisted principally of Catalans.[19] In 1812, a group of blacks and mulattoes staged a rebellion, with the goal of annexation to the Republic of Haiti. On August 15 and 16, mulattoes José Leocadio, Pedro Seda, and Pedro Henriquez, with other conspirators, attacked the Mendoza hacienda in Mojarra in the municipality of Guerra near the capital. Seda and Henriquez were apprehended and executed; Leocadio was captured within days, hanged, dismembered, and boiled in oil. A year later enslaved laborers in the rural community El Chavón also rebelled, but they were quickly caught and executed.

Spain's hold over Santo Domingo remained precarious. The arrival of the fugitive Simón Bolívar and his followers in Haiti in 1815 alarmed the Spanish authorities in Santo Domingo. Following the rebellion of the Army in Spain during 1820, which restored the liberal constitution, some of the colonial administrators in Santo Domingo broke with the mother country; and on December 1, 1821, the Spanish Lieutenant Governor, José Núñez de Cáceres, proclaimed the independence of "Spanish Haiti".

Dominican leaders—recognizing their vulnerability both to Spanish and to Haitian attack and also seeking to maintain their slaves as property—attempted to annex themselves to Gran Colombia. While this request was in transit, Jean-Pierre Boyer, the ruler of Haiti, invaded Santo Domingo on February 9 with a 10,000-man army. Having no capacity to resist, Núñez de Cáceres surrendered the capital on February 9, 1822.

Unification of Hispaniola 1822–1844

The twenty-two-year Haitian occupation that followed is recalled by Dominicans as a period of brutal military rule, though the reality is more complex. It led to large-scale land expropriations and failed efforts to force production of export crops, impose military services, restrict the use of the Spanish language, and eliminate traditional customs such as cockfighting. It reinforced Dominicans' perceptions of themselves as different from Haitians in "language, race, religion and domestic customs".[20] Yet, this was also a period that definitively ended slavery as an institution in the eastern part of the island.

Haiti's constitution forbade whites from owning land, and the major landowning families were forcibly deprived of their properties. Most emigrated to the Spanish colonies of Cuba and Puerto Rico, or to independent Gran Colombia, usually with the encouragement of Haitian officials, who acquired their lands. The Haitians, who associated the Catholic Church with the French slave-masters who had exploited them before independence, confiscated all church property, deported all foreign clergy, and severed the ties of the remaining clergy to the Vatican. Santo Domingo's university, the oldest in the Western Hemisphere, lacking students, teachers, and resources, closed down. In order to receive diplomatic recognition from France, Haiti was forced to pay an indemnity of 150 million francs to the former French colonists, which was subsequently lowered to 60 million francs, and Haiti imposed heavy taxes on the eastern part of the island. Since Haiti was unable to adequately provision its army, the occupying forces largely survived by commandeering or confiscating food and supplies at gunpoint.

Attempts to redistribute land conflicted with the system of communal land tenure (terrenos comuneros), which had arisen with the ranching economy, and newly emancipated slaves resented being forced to grow cash crops under Boyer's Code Rural.[21] In rural areas, the Haitian administration was usually too inefficient to enforce its own laws. It was in the city of Santo Domingo that the effects of the occupation were most acutely felt, and it was there that the movement for independence originated.

Independence: First Republic 1844–1861

| War of Independence | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Battle deaths (1844–45) < 20[22] |

Battle deaths (1844–45) c. 3,000[22] | ||||||

| The Dominicans reportedly did not hesitate to attack with the odds against them of sometimes five to one.[23] An eye-witness described one of these fights, in which the two parties approached each shouting with all their might; then the Haitians would fire in the air, thinking the noise would scare their opponents; but the latter, drawing their swords, would rush in, and compel the Haitians to seek cover, and thus sometimes a whole day would be spent by these people, to the number of several hundreds, without any one being hurt, and yet it would be called a great battle, each side claiming a victory.[23] | |||||||

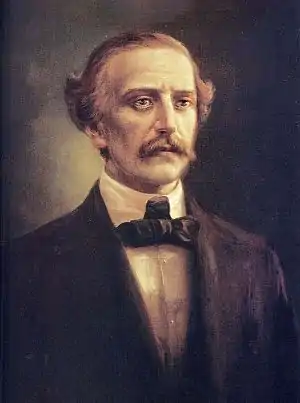

On July 16, 1838, Juan Pablo Duarte together with Pedro Alejandrino Pina, Juan Isidro Pérez, Felipe Alfau, Benito González, Félix María Ruiz, Juan Nepumoceno Ravelo and Jacinto de la Concha founded a secret society called La Trinitaria to win independence from Haiti. A short time later, they were joined by Ramón Matías Mella, and Francisco del Rosario Sánchez. In 1843 they allied with a Haitian movement in overthrowing Boyer. Because they had revealed themselves as revolutionaries working for Dominican independence, the new Haitian president, Charles Rivière-Hérard, exiled or imprisoned the leading Trinitarios (Trinitarians). At the same time, Buenaventura Báez, an Azua mahogany exporter and deputy in the Haitian National Assembly, was negotiating with the French Consul-General for the establishment of a French protectorate. In an uprising timed to preempt Báez, on February 27, 1844, the Trinitarios declared independence from Haiti, backed by Pedro Santana, a wealthy cattle-rancher from El Seibo who commanded a private army of peons who worked on his estates.

First Republic

The Dominican Republic's first constitution was adopted on November 6, 1844. The state was commonly known as Santo Domingo in English until the early 20th century.[24] It featured a presidential form of government with many liberal tendencies, but it was marred by Article 210, imposed by Pedro Santana on the constitutional assembly by force, giving him the privileges of a dictatorship until the war of independence was over. These privileges not only served him to win the war but also allowed him to persecute, execute and drive into exile his political opponents, among which Duarte was the most important. In Haiti after the fall of Boyer, black leaders had ascended to the power once enjoyed exclusively by the mulatto elite.[25]

Hérard sent three columns of Haitian troops, each numbering 10,000 men, to reestablish his authority. In the south, Santana defeated Hérard at the Battle of Azua on March 19. Dominican forces suffered no casualties in the battle,[26] while the Haitians sustained over 1,000 killed.[27] In the north, Dominican General José María Imbert defeated the Haitian column led by Jean-Louis Pierrot at the Battle of Santiago on March 30. Over 600 Haitians were killed while the Dominicans suffered no casualties.[26] Events at sea also went poorly for the Haitians. Three Dominican schooners under the command of Juan Bautista Cambiaso intercepted a Haitian brigantine and two schooners which were bombarding shore targets. In the ensuing engagement, all three Haitian vessels were sunk, ensuring Dominican naval superiority for the rest of the war.[28] On August 6, 1845, the new Haitian president, Luis Pierrot, launched a new invasion. On September 17, Dominican General José Joaquín Puello defeated the Haitian vanguard near the frontier at Estrelleta where the Dominican square, with bayonets, repulsed a Haitian cavalry charge. The Dominicans suffered no deaths during the battle and only three wounded. On November 27, 1845, Dominican General Francisco Antonio Salcedo defeated the Haitian army at the Battle of Beler. Salcedo was supported by Admiral Juan Bautista Cambiaso's squadron of three schooners, which blockaded the Haitian port of Cap-Haïtien.[28] Haitian losses were 350 killed and 10 captured; the Dominicans lost 16 killed.

Santana used the ever-present threat of Haitian invasion as a justification for consolidating dictatorial powers. For the Dominican elite—mostly landowners, merchants and priests—the threat of re-annexation by more populous Haiti was sufficient to seek protection from a foreign power. Offering the deepwater harbor of Samaná bay as bait, over the next two decades, negotiations were made with Britain, France, the United States and Spain to declare a protectorate over the country.

The constant threat and fear of renewed Haitian intervention required all men of fighting age to take up arms in defense against the Haitian military. Theoretically, fighting age was generally defined as between fifteen and eighteen years of age to forty or fifty years. Despite wide, popular glorification of military service, many in the ranks of the Liberation Army were mutinous and desertion rates were high despite penalties as severe as death for shirking the obligation of military service.

Without adequate roads, the regions of the Dominican Republic developed in isolation from one another. In the south, the economy was dominated by cattle-ranching (particularly in the southeastern savannah) and cutting mahogany and other hardwoods for export. This region retained a semi-feudal character, with little commercial agriculture, the hacienda as the dominant social unit, and the majority of the population living at a subsistence level. In the Cibao Valley, the nation's richest farmland, peasants supplemented their subsistence crops by growing tobacco for export, mainly to Germany. Tobacco required less land than cattle ranching and was mainly grown by smallholders, who relied on itinerant traders to transport their crops to Puerto Plata and Monte Cristi. Santana antagonized the Cibao farmers, enriching himself and his supporters at their expense by resorting to multiple peso printings that allowed him to buy their crops for a fraction of their value. In 1848, he was forced to resign and was succeeded by his vice-president, Manuel Jimenes.

After returning to lead Dominican forces against a new Haitian invasion in 1849, Santana marched on Santo Domingo, deposing Jimenes. At his behest, Congress elected Buenaventura Báez as President, but Báez was unwilling to serve as Santana's puppet, challenging his role as the country's acknowledged military leader. Báez determined to take the offensive against Haiti. His seamen under the French adventurer, Fagalde, raided the Haitian coasts, plundered seaside villages, as far as Cape Dame Marie, and butchered crews of captured enemy ships. In 1853 Santana was elected president for his second term, forcing Báez into exile. Three years later, after repulsing the last Haitian invasion, he negotiated a treaty leasing a portion of Samaná Peninsula to a U.S. company; popular opposition forced him to abdicate, enabling Báez to return and seize power. With the treasury depleted, Báez printed eighteen million uninsured pesos, purchasing the 1857 tobacco crop with this currency and exporting it for hard cash at immense profit to himself and his followers. The Cibanian tobacco planters, who were ruined when inflation ensued, revolted, recalling Santana from exile to lead their rebellion. After a year of civil war, Santana seized Santo Domingo and installed himself as president.

In 1860, a group of Americans tried unsuccessfully to take over the small Dominican island of Alto Velo off the southwestern border coast of Hispaniola.

Spanish colony: 1861–1865

| War of Restoration | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 30,000[29] | 63,000[30] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 10,888 Spanish soldiers fell in combat; disease claimed 30,000 Spaniards. | |||||||

Pedro Santana inherited a bankrupt government on the brink of collapse. Having failed in his initial bids to secure annexation by the U.S. or France, Santana initiated negotiations with Queen Isabella II of Spain and the Captain-General of Cuba to have the island reconverted into a Spanish colony. The American Civil War rendered the United States incapable of enforcing the Monroe Doctrine. In Spain, Prime Minister Don Leopoldo O'Donnell advocated renewed colonial expansion, waging a campaign in northern Morocco that conquered the city of Tetuan. In March 1861, Santana officially restored the Dominican Republic to Spain.

Santana initially was named Capitan-General of the new Spanish province, but it soon became obvious that Spanish authorities planned to deprive him of his power, leading him to resign in 1862. Restrictions on trade, discrimination against the mulatto majority, and an unpopular campaign by the new Spanish Archbishop, Bienvenido Monzón, against extramarital unions, which were widespread after decades of abandonment by the Catholic Church, all fed resentment of Spanish rule.

Monzón also persecuted Freemasons, whose activities were widespread before the annexation, barring them from communion until they canted their vows and gave up their Masonic documents and practices. Monzón actively persecuted Protestants as well. Protestant churches in Samaná and Santo Domingo were taken over, burned, or confiscated for military purposes, forcing many Dominican Protestants to consider moving to Haiti in search of religious toleration.

On August 16, 1863, a national war of restoration began in Santiago, where the rebels established a provisional government. "Before God, the entire world, and the throne of Castile, just and legal reasons have obliged us to take arms to restore the Dominican Republic and reconquer our liberty," the provisional government's declaration of independence read.[31] Dominicans were divided. Some fought for the reserve forces alongside Spanish troops.[Note 1] Santana returned to lead them.[Note 2]

War of Restoration

The Spanish forces of the Cibao valley were obliged to concentrate in Fort San Luis, at Santiago, where they were besieged by the insurgents. The rebels had possession of three forts which face the Puerto Plata road. They undertook to make a general assault on the fort where the Spanish troops were concentrated. The besieged forces let the enemy's bands come near, and when within musket range opened a tremendous fire of artillery, which, committing great destruction, drove them back in disorder. They, however, tried their luck again, and this time set fire to the houses of the town in different parts and made their attack in the midst of the conflagration. Spanish reinforcements arrived and charged the insurgents, who received them with grapeshot and musketry from the three forts which they held. The insurgents were repulsed and the forts retaken at the point of the bayonet. The garrison of Santiago abandoned the city and marched to Puerto Plata, the main northern port, attacked by Dominicans all the way. The Spaniards reportedly lost 1,300 men.[32] They joined the garrison in the fort at Puerto Plata, leaving the city to be pillaged by the rebels. Eventually, 600 Spanish sallied out and drove off the rebels, with help from the cannon of the fort, but by then the city had been plundered and burnt almost out of existence. The damage to Santiago and Puerto Plata was estimated at $5,000,000. By mid-November, virtually the whole garrisons of Cuba and Puerto Rico were deployed on Santo Domingo and 8,000 troops had been sent from Europe, diverted from deployment in Morocco. The Spanish navy had complete command of the sea and used a fleet of paddle wheel steamers to transport troops to, and around, the island.

As the fighting continued, racist incidents became more acute. Spanish soldiers were openly hostile to Dominicans of color, and incidents of unprovoked violence against black Dominicans and migrants in the towns proliferated.[33] Perhaps because of the fright that Spain would seek to make Santo Domingo an enslaved twin of Cuba, Dominicans were said to fight like "supernatural fiends" with a "desperate" intensity.[34] By early 1864, the Spanish army, unable to contain guerrilla resistance, had suffered 1,000 killed in action and 9,000 dead from disease.[35] Spanish colonial authorities encouraged Queen Isabella II to abandon the island, seeing the occupation as a nonsensical waste of troops and money. However, the rebels were in a state of political disarray and proved unable to present a cohesive set of demands. The first president of the provisional government, Pepillo Salcedo (allied with Báez) was deposed by General Gaspar Polanco in September 1864, who, in turn, was deposed by General Antonio Pimentel three months later. The rebels formalized their provisional rule by holding a national convention in February 1865, which enacted a new constitution, but the new government exerted little authority over the various regional guerrilla caudillos, who were largely independent of one another.

Unable to extract concessions from the disorganized rebels, when the American Civil War ended, in March 1865, Queen Isabella annulled the annexation and independence was restored, with the last Spanish troops departing by July.[36] More than 7,000 Dominicans perished in battles and epidemics.[29] Relations between the Dominican Republic and Haiti were tense once the new Dominican government came to power since Haitian President Fabre Geffrard had refused to support the independence movement out of fear of Spanish reprisals.[37] Within three years after fighting ended in Santo Domingo, uprisings began in both remaining Spanish colonies. In both islands, Dominican veterans joined the independence fight. Within the decade, Spanish colonialism began to crumble, and rebels won emancipation.

Restoration: Second Republic 1865–1916

Second Republic

By the time the Spanish departed, most of the main towns lay in ruins and the island was divided among several dozen caudillos. José María Cabral controlled most of Barahona and the southwest with the support of Báez's mahogany-exporting partners, while cattle rancher Cesáreo Guillermo assembled a coalition of former Santanista generals in the southeast, and Gregorio Luperón controlled the north coast. Once the Spanish were vanquished, the numerous military and guerrilla leaders began to fight among themselves. From the Spanish withdrawal to 1879, there were twenty-one changes of government and at least fifty military uprisings.[38] Haiti served as a haven for Dominican political exiles and a base of operations for insurgents, often with the support of the Haitian government, during the frequent civil wars and revolutions of the period.

In the course of these conflicts, two parties emerged. The Partido Rojo (Literally "Red Party") represented the southern cattle ranching latifundia and mahogany-exporting interests, as well as the artisans and laborers of Santo Domingo, and was dominated by Báez, who continued to seek annexation by a foreign power. The Partido Azul (literally "Blue Party"), led by Luperón, represented the tobacco farmers and merchants of the Cibao and Puerto Plata and was nationalist and liberal in orientation. During these wars, the small and corrupt national army was far outnumbered by militias organized and maintained by local caudillos who set themselves up as provincial governors. These militias were filled out by poor farmers or landless plantation workers impressed into service who usually took up banditry when not fighting in revolution.

Within a month of the nationalist victory, Cabral, whose troops were the first to enter Santo Domingo, ousted Pimentel, but a few weeks later General Guillermo led a rebellion in support of Báez, forcing Cabral to resign and allowing Báez to retake the presidency in October. Báez was overthrown by the Cibao farmers under Luperón, leader of the Partido Azul, the following spring, but Luperón's allies turned on each other and Cabral reinstalled himself as president in a coup in 1867. After bringing several Azules ("Blues") into his cabinet the Rojos ("Reds") revolted, returning Báez to power. In 1869, Báez negotiated a treaty of annexation with the United States.[39] Supported by U.S. Secretary of State William Seward, who hoped to establish a Navy base at Samaná, in 1871 the treaty was defeated in the United States Senate through the efforts of abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner.[40]

In 1874, the Rojo governor of Puerto Plata, Ignacio Maria González Santín, staged a coup in support of an Azul rebellion but was deposed by the Azules two years later. In February 1876, Ulises Espaillat, backed by Luperón, was named President, but ten months later troops loyal to Báez returned him to power. One year a new rebellion allowed González to seize power, only to be deposed by Cesáreo Guillermo in September 1878, who was in turn deposed by Luperón in December 1879. Ruling the country from his hometown of Puerto Plata, enjoying an economic boom due to increased tobacco exports to Germany, Luperón enacted a new constitution setting a two-year presidential term limit and providing for direct elections, suspended the semi-formal system of bribes and initiated construction on the nation's first railroad, linking the town of La Vega with the port of Sánchez on Samaná Bay.

The Ten Years' War in Cuba brought Cuban sugar planters to the country in search of new lands and security from the insurrection that freed their slaves and destroyed their property. Most settled in the southeastern coastal plain, and, with assistance from Luperón's government, built the nation's first mechanized sugar mills. They were later joined by Italians, Germans, Puerto Ricans and Americans in forming the nucleus of the Dominican sugar bourgeoisie, marrying into prominent families to solidify their social position. Disruptions in global production caused by the Ten Years' War, the American Civil War and the Franco-Prussian War allowed the Dominican Republic to become a major sugar exporter. Over the following two decades, sugar surpassed tobacco as the leading export, with the former fishing hamlets of San Pedro de Macorís and La Romana transformed into thriving ports. To meet their need for better transportation, over 300 miles of private rail-lines were built by and serving the sugar plantations by 1897.[41] An 1884 slump in prices led to a wage freeze, and a subsequent labor shortage was filled by migrant workers from the Leeward Islands—the Virgin Islands, St. Kitts and Nevis, Anguilla, and Antigua (referred to by Dominicans as cocolos).[42] These English-speaking blacks were often victims of racism, but many remained in the country, finding work as stevedores and in railroad construction and sugar refineries.

Puerto Ricans were imported to work under near-slave conditions on Puerto Rican-owned sugar plantations in the Dominican Republic, in the area of La Romana, during the nineteenth century. Others worked in coffee fields. Arabs began to arrive in the Dominican Republic during the latter part of the nineteenth century. They were widely accused of being dirty and of having bad manners and habits, and the government was reproached for having allowed these immigrants into the nation.[43] Since upper-class Dominicans refused to give membership to wealthy Arabs to their private clubs like the exclusive Club de Unión, the Arabs created their own.[Note 3] During the U.S. occupation of 1916–24, peasants from the countryside, called Gavilleros, would not only kill U.S. Marines, but would also attack and kill Arab vendors traveling through the countryside.[44]

Ulises Heureaux and U.S. protectorate

Allying with the emerging sugar interests, the dictatorship of General Ulises Heureaux, who was popularly known as Lilís, brought unprecedented stability to the island through an iron-fisted rule that lasted almost two decades. The son of a Haitian father and a mother from St. Thomas, Virgin Islands, Lilís was distinguished by his blackness from most Dominican political leaders, with the exception of Luperón. He served as President 1882–1883, 1887, and 1889–1899, wielding power through a series of puppet presidents when not occupying the office. Incorporating both Rojos and Azules into his government, he developed an extensive network of spies and informants to crush potential opposition. His government undertook a number of major infrastructure projects, including the electrification of Santo Domingo, the beginning of telephone and telegraph service, the construction of a bridge over the Ozama River, and the completion of a single-track railroad linking Santiago and Puerto Plata, financed by the Amsterdam-based Westendorp Co.[45]

Lilís's dictatorship was dependent upon heavy borrowing from European and American banks to enrich himself, stabilize the existing debt, strengthen the bribe system, pay for the army, finance infrastructural development and help set up sugar mills. However, sugar prices underwent a steep decline in the last two decades of the 19th century. When the Westendorp Co. went bankrupt in 1893, he was forced to mortgage the nation's customs fees, the main source of government revenues, to a New York financial firm called the San Domingo Improvement Co. (SDIC), which took over its railroad contracts and the claims of its European bondholders in exchange for two loans, one of $1.2 million and the other of £2 million.[46] As the growing public debt made it impossible to maintain his political machine, Heureaux relied on secret loans from the SDIC, sugar planters and local merchants. In 1897, with his government virtually bankrupt, Lilís printed five million uninsured pesos, known as papeletas de Lilís, ruining most Dominican merchants and inspiring a conspiracy that ended in his death. In 1899, when Lilís was assassinated by the Cibao tobacco merchants whom he had been begging for a loan, the national debt was over $35 million, fifteen times the annual budget.[47]

The six years after Lilís's death witnessed four revolutions and five different presidents.[48] The Cibao politicians who had conspired against Heureaux—Juan Isidro Jimenes, the nation's wealthiest tobacco planter, and General Horacio Vásquez—after being named President and Vice-President, quickly fell out over the division of spoils among their supporters, the Jimenistas and Horacistas. Troops loyal to Vásquez overthrew Jimenes in 1903, but Vásquez was deposed by Jimenista General Alejandro Woss y Gil, who seized power for himself. The Jimenistas toppled his government, but their leader, Carlos Morales, refused to return power to Jimenes, allying with the Horacistas, and he soon faced a new revolt by his betrayed Jimenista allies.

In 1904, American warships bombarded insurgents in Santo Domingo for insulting the United States flag and damaging an American steamer.[49]

With the nation on the brink of defaulting, France, Germany, Italy and the Netherlands sent warships to Santo Domingo to press the claims of their nationals. In order to preempt military intervention, United States president Theodore Roosevelt introduced the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, declaring that the United States would assume responsibility for ensuring that the nations of Latin America met their financial obligations. In January 1905, under this corollary, the United States assumed administration of the Dominican Republic's customs. Under the terms of this agreement, a Receiver-General, appointed by the U.S. President, kept 55% of total revenues to pay off foreign claimants, while remitting 45% to the Dominican government. After two years, the nation's external debt was reduced from $40 million to $17 million.[50] In 1907, this agreement was converted into a treaty, transferring control over customs receivership to the U.S. Bureau of Insular Affairs and providing a loan of $20 million from a New York bank as payment for outstanding claims, making the United States the Dominican Republic's only foreign creditor.[51] In 1905, the Dominican Peso was replaced by the U.S. Dollar.[52]

In 1906, Morales resigned, and Horacista vice-president Ramon Cáceres became president. After suppressing a rebellion in the northwest by Jimenista General Desiderio Arias, his government brought political stability and renewed economic growth, aided by new American investment in the sugar industry. However, his assassination in 1911, for which Morales and Arias were at least indirectly responsible, once again plunged the republic into chaos. For two months, executive power was held by a civilian junta dominated by the chief of the army, General Alfredo Victoria. The surplus of more than 4 million pesos left by Cáceres was quickly spent to suppress a series of insurrections.[53] He forced Congress to elect his uncle, Eladio Victoria, as President, but the latter was soon replaced by the neutral Archbishop Adolfo Nouel. After four months, Nouel resigned and was succeeded by Horacista Congressman José Bordas Valdez, who aligned with Arias and the Jimenistas to maintain power. In 1913, Vásquez returned from exile in Puerto Rico to lead a new rebellion. In June 1914 U.S. President Woodrow Wilson issued an ultimatum for the two sides to end hostilities and agree on a new president, or have the United States impose one. After the provisional presidency of Ramón Báez, Jimenes was elected in October, and soon faced new demands, including the appointment of an American director of public works and financial advisor and the creation of a new military force commanded by U.S. officers. The Dominican Congress rejected these demands and began impeachment proceedings against Jimenes. The United States occupied Haiti in July 1915, with the implicit threat that the Dominican Republic might be next. Jimenes's Minister of War Desiderio Arias staged a coup d'état in April 1916, providing a pretext for the United States to occupy the Dominican Republic.

United States occupation: 1916–1924

Conventional campaign

| Pacification of the Dominican Republic | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 1,000 militia | 1,800 marines | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 100 casualties[54] |

Las Trencheras Ridge

| ||||||

| By the time U.S. forces were withdrawn in 1924, 144 Marines had been killed in action.[57] | |||||||

United States Marines landed in Santo Domingo on May 15, 1916. Prior to their landing, Jimenes resigned, refusing to exercise an office "regained with foreign bullets".[58] On June 1, Marines occupied Monte Cristi and Puerto Plata. They occupied Monte Cristi without meeting resistance, but at Puerto Plata they had to fight their way into the city under heavy but inaccurate fire from about 500 pro-Arias irregulars. During this landing the Marines sustained several casualties, including the death of Captain Herbert J. Hirshinger, the first Marine killed in combat in the Dominican campaign. Insurgent losses, while never accurately determined, were light.

A column of Marines under Colonel Joseph H. Pendleton marched toward Santiago de los Caballeros, where rebel forces had established a government. Along the way, Dominicans tore up the railroad tracks, forcing Marines to walk. They also burned bridges, delaying the march.[59] Twenty-four miles into the march, the Marines encountered Las Trencheras, two fortified ridges the Dominicans had long thought invulnerable: the Spanish had been defeated there in 1864. At 08:00 hours on June 27, Pendleton ordered his artillery to pound the ridgeline. Machine guns offered covering fire. A bayonet attack cleared the first ridge. Rifle fire removed the rebels who were threatening from atop the second.[60] The significance of this battle lies in the fact that this was the first experience of Marines advancing with the support of modern artillery and machine guns.

A week later, the Marines encountered another entrenched rebel force at Guayacanas. The rebels kept up single-shot fire against the automatic weapons of the Marines before the Marines drove them off. The battle was important in the history of the 4th Marines insofar as the regiment subsequently acquired its first Medal of Honor recipient. First Sergeant Roswell Winans, while manning his machine gun, displayed such exceptional valor that he was later awarded the nation's highest military honor. Sergeant Winans obtained his award for the bravado that he demonstrated when for a time he single-handedly raked enemy lines with his weapon. Then, when the gun jammed, he set about clearing it in full view of the Dominicans without regard to his personal safety. With his supporters defeated, Arias surrendered on July 5 in exchange for being pardoned.[61]

At San Francisco de Macorís, Governor Juan Pérez, a supporter of Arias, refused to recognize the U.S. military government. Using some 300 released prisoners, he was preparing to defend the old Spanish colonial structure, the Fortazela. On November 29 U.S. Marine Lt. Ernest C. Williams, whose detachment was billeted in San Francisco, charged the closing gates of the fort at nightfall with a dozen Marines. Eight were shot down; the others, including Williams, forced their way in and seized the old structure. Another Marine detachment seized the police station. Reinforcements from nearby detachments soon suppressed the uprising.[62] The Marine Corps' subsequent efforts at "state-building", as it is commonly known today, received little assistance from Dominicans. Dominican elites, animated by nationalist resentment of the takeover of their country, refused to help the foreigners restructure their government and society.

Occupation

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The Dominican Congress elected Dr. Francisco Henríquez y Carvajal as President, but in November, after he refused to meet the U.S. demands, Wilson announced the imposition of a U.S. military government, with Rear Admiral Harry Shepard Knapp as Military Governor. The American military government implemented many of the institutional reforms carried out in the United States during the Progressive Era, including reorganization of the tax system, accounting and administration, expansion of primary education, the creation of a nationwide police force to unify the country, and the construction of a national system of roads, including a highway linking Santiago to Santo Domingo.

Despite the reforms, virtually all Dominicans resented the loss of their sovereignty to foreigners, few of whom spoke Spanish or displayed much real concern for the nation's welfare, and the military government, unable to win the backing of any prominent Dominican political leaders, imposed strict censorship laws and imprisoned critics of the occupation. In 1920, U.S. authorities enacted a Land Registration Act, which broke up the terrenos comuneros and dispossessed thousands of peasants who lacked formal titles to the lands they occupied, while legalizing false titles held by the sugar companies. In the southeast, dispossessed peasants formed armed bands, called gavilleros, waging a guerrilla war that lasted six years, with most of the fighting in Hato Mayor and El Seibo. At any given time, the Marines faced eight to twelve such bands each composed of several hundred followers. The guerrillas benefited from a superior knowledge of the terrain and the support of the local population, and the Marines relied on increasingly brutal counterinsurgency methods. However, rivalries between various gavilleros often led them to fight against one another, and even cooperate with occupation authorities. In addition, cultural schisms between the campesinos (i.e. rural people, or peasants) and city dwellers prevented the guerrillas from cooperating with the urban middle-class nationalist movement.

The most notorious rebel of Seibo was a daring Dominican bandit with the nom de guerre of Vicentico Evangelista. In March 1917 he brutally executed two American civilians, engineers from an American-owned plantation, who were lashed to trees, savagely hacked with machetes, then left dangling for ravenous wild boars.[63] He led Marine pursuers on a merry chase before surrendering on July 5 of that year. Two days later Vicentico was shot and killed by Marines "while trying to escape". On August 13, 1918, a five-man Marine patrol was ambushed near Manchado; four Marines were killed and the survivor wounded. By 1919 the Marines had received radios that made it easier to coordinate their efforts and six Curtiss "Jenny" biplanes that allowed them to expand the reach of their patrolling and even to bomb some guerrilla outposts. The unrest in the eastern provinces lasted until 1922 when the guerrillas finally agreed to surrender in return for amnesty. During the course of the campaign between 1916 and 1922, the Marines claim to have killed or wounded 1,137 "bandits", while 20 Marines were killed and 67 wounded.[56] (Forty U.S. sailors died separately when a hurricane wrecked their ship on Santo Domingo's rocky shore.)

In the San Juan valley, near the border with Haïti, followers of a Vodu faith healer named Liborio resisted the occupation and aided the Haitian cacos in their war against the Americans, until his death in 1922. When the Haitian and Dominican forces began to fight the U.S. interventions, they suffered immensely due to the superiority of U.S. training and technology. They were poorly armed and a "minority of them carried old-model black-powder rifles; the majority went into battle with swords, machetes, and pikes."[64] The obsolete weapons as well as the lack of training and institutional control over the regional armed forces ensured American military preeminence in the region.

.jpg.webp)

In what was referred to as la danza de los millones, with the destruction of European sugar-beet farms during World War I, sugar prices rose to their highest level in history, from $5.50 in 1914 to $22.50 per pound in 1920. Dominican sugar exports increased from 122,642 tons in 1916 to 158,803 tons in 1920, earning a record $45.3 million.[65] However, European beet sugar production quickly recovered, which, coupled with the growth of global sugar cane production, glutted the world market, causing prices to plummet to only $2.00 by the end of 1921. This crisis drove many of the local sugar planters into bankruptcy, allowing large U.S. conglomerates to dominate the sugar industry. By 1926, only twenty-one major estates remained, occupying an estimated 520,000 acres (2,100 km2). Of these, twelve U.S.-owned companies owned more than 81% of this total area.[66] While the foreign planters who had built the sugar industry integrated into Dominican society, these corporations expatriated their profits to the United States. As prices declined, sugar estates increasingly relied on Haitian laborers. This was facilitated by the military government's introduction of regulated contract labor, the growth of sugar production in the southwest, near the Haitian border, and a series of strikes by cocolo cane cutters organized by the Universal Negro Improvement Association.

Withdrawal

Fortaleza San Luis (Santiago de los Caballeros)

In the 1920 United States presidential election Republican candidate Warren Harding criticized the occupation and promised eventual U.S. withdrawal. While Jimenes and Vásquez sought concessions from the United States, the collapse of sugar prices discredited the military government and gave rise to a new nationalist political organization, the Dominican National Union, led by Dr. Henríquez from exile in Santiago de Cuba, Cuba, which demanded unconditional withdrawal. They formed alliances with frustrated nationalists in Puerto Rico and Cuba, as well as critics of the occupation in the United States itself, most notably The Nation and the Haiti-San Domingo Independence Society. In May 1922, a Dominican lawyer, Francisco Peynado, went to Washington, D.C. and negotiated what became known as the Hughes–Peynado Plan. It stipulated the immediate establishment of a provisional government pending elections, approval of all laws enacted by the U.S. military government, and the continuation of the 1907 treaty until all the Dominican Republic's foreign debts had been settled. On October 1, Juan Bautista Vicini, the son of a wealthy Italian immigrant sugar planter, was named provisional president, and the process of U.S. withdrawal began. The principal legacy of the occupation was the creation of a National Police Force, used by the Marines to help fight against the various guerrillas, and later the main vehicle for the rise of Rafael Trujillo.

In contrast to the much romanticized fighting of the Rough Riders at San Juan Hill in Cuba almost two decades earlier, the Marines' anti-rebel campaigns in the Dominican Republic were hot, often godlessly uncomfortable, and largely devoid of heroism and glory.[67]

The rise and fall of Trujillo: Third Republic 1924–1965

Horacio Vásquez 1924–1930

The occupation ended in 1924, with a democratically elected government under president Vásquez. The Vásquez administration brought great social and economic prosperity to the country and respected political and civil rights. Rising export commodity prices and government borrowing allowed the funding of public works projects and the expansion and modernization of Santo Domingo.[68]

Though considered to be a relatively principled man, Vásquez had risen amid many years of political infighting. In a move directed against his chief opponent Federico Velasquez, in 1927 Vásquez agreed to have his term extended from four to six years. The change was approved by the Dominican Congress, but was of debatable legality; "its enactment effectively invalidated the constitution of 1924 that Vásquez had previously sworn to uphold."[68] Vásquez also removed the prohibition against presidential reelection and postulated himself for another term in elections to be held in May 1930. However, his actions had by then led to doubts that the contest could be fair.[68] Furthermore, these elections took place amid economic problems, as the Great Depression had dropped sugar prices to less than one dollar per pound.

In February, a revolution was proclaimed in Santiago by a lawyer named Rafael Estrella Ureña. When the commander of the Guardia Nacional Dominicana (the new designation of the armed force created under the Occupation), Rafael Leonidas Trujillo Molina, ordered his troops to remain in their barracks, the sick and aging Vásquez was forced into exile and Estrella proclaimed provisional president. In May, Trujillo was elected with 95% of the vote, having used the army to harass and intimidate electoral personnel and potential opponents. After his inauguration in August, at his request, the Dominican Congress proclaimed the beginning of the 'Era of Trujillo'.[68]

The era of Trujillo 1931–1961

Trujillo established absolute political control while promoting economic development—from which mainly he and his supporters benefitted—and severe repression of domestic human rights.[69] Trujillo treated his political party, El Partido Dominicano (The Dominican Party), as a rubber-stamp for his decisions. The true source of his power was the Guardia Nacional—larger, better armed, and more centrally controlled than any military force in the nation's history. By disbanding the regional militias, the Marines eliminated the main source of potential opposition, giving the Guard "a virtual monopoly on power".[70] By 1940, Dominican military spending was 21% of the national budget.[71] At the same time, he developed an elaborate system of espionage agencies. By the late 1950s, there were at least seven categories of intelligence agencies, spying on each other as well as the public. All citizens were required to carry identification cards and good-conduct passes from the secret police. Obsessed with adulation, Trujillo promoted an extravagant cult of personality. When a hurricane struck Santo Domingo in 1930, killing over 3,000 people, he rebuilt the city and renamed it Ciudad Trujillo: "Trujillo City"; he also renamed the country's and the Caribbean's highest mountain, Pico Duarte (Duarte Peak), Pico Trujillo. Over 1,800 statues of Trujillo were built, and all public works projects were required to have a plaque with the inscription "Era of Trujillo, Benefactor of the Fatherland".[72]

As sugar estates turned to Haiti for seasonal migrant labor, increasing numbers settled in the Dominican Republic permanently. The census of 1920, conducted by the U.S. occupation government, gave a total of 28,258 Haitians living in the country; by 1935 there were 52,657.[73] In October 1937, Trujillo ordered the massacre of up to 38,000 Haitians,[74] the alleged justification being Haiti's support for Dominican exiles plotting to overthrow his regime. The killings were fuelled by the racism of Dominicans, who also disdained the manual labour which Haitians performed in conditions of near-slavery.[75] This event later became known as the Parsley Massacre because of the story that Dominican soldiers identified Haitians by their inability to pronounce the Spanish word perejil.[76] Subsequently, during the first half of 1938, thousands more Haitians were forcibly deported and hundreds killed in the southern frontier region.[77]

So that news of the slaughter would not leak out, Trujillo clamped tight censorship on all mail and news dispatches. A shocked American missionary, Father Barnes, wrote about the massacre in a letter to his sister. It never reached her. He was found on the floor of his home, murdered brutally.[78] But the news leaked out, stirring a decision by the United States, Mexico, and Cuba to make a joint investigation. General Hugh Johnson, a former New Deal official, made a national broadcast describing how Haitian women had been stabbed and mutilated, babies bayoneted, and men tied up and thrown into the sea to drown.[78] The massacre was the result of a new policy which Trujillo called the "Dominicanisation of the frontier". Place names along the border were changed from Creole and French to Spanish, the practice of Voodoo was outlawed, quotas were imposed on the percentage of foreign workers that companies could hire, and a law was passed preventing Haitian workers from remaining after the sugar harvest. Another example of repression and prejudice came about a year after Trujillo's death, in December 28, 1962, when the mainly Dominico-Haitian[79] peasant community of Palma Sola, which challenged the racial, political, and economic situation of the country, was bombarded with napalm by the Dominican Air Force.[80]

Although Trujillo sought to emulate Generalissimo Francisco Franco, he welcomed Spanish Republican refugees following the Spanish Civil War. During the Holocaust in the Second World War, the Dominican Republic took in many Jews fleeing Hitler who had been refused entry by other countries. The Jews settled in Sosua.[81] These decisions arose from a policy of blanquismo, closely connected with anti-Haitian xenophobia, which sought to add more light-skinned individuals to the Dominican population by promoting immigration from Europe. As part of the Good Neighbor policy, in 1940, the U.S. State Department signed a treaty with Trujillo relinquishing control over the nation's customs. When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor Trujillo followed the United States in declaring war on the Axis powers, even though he had openly professed admiration for Hitler and Mussolini. During the Cold War, he maintained close ties to the United States, declaring himself the world's "Number One Anticommunist" and becoming the first Latin American President to sign a Mutual Defense Assistance Agreement with the United States. One tactical asset of the United States in the Cold War was the missile tracking system established across the region, which comprised a series of individual stations in neighboring countries. One of these stations was located in the Dominican Republic, requiring bilateral negotiations to establish the facility, and cooperation to operate it. The ranks of the U.S. military mission in the Dominican Republic swelled, as aircraft trainers and mechanics joined the attachés of the four service branches and their staffs working at the U.S. embassy. The missile tracking station and the military mission were the strongest Cold War ties between the United States and the Dominican Republic, but they became liabilities as the relationship soured.

Soon after the end of World War II, Trujillo constructed an arms factory at San Cristóbal. It made hand grenades, gunpowder, dynamite, revolvers, automatic rifles, carbines, submachine guns, light machine guns, antitank guns, and munitions. In addition, some quantities of mortars and aerial bombs were produced and light artillery rebuilt.[82] Trujillo's increasingly powerful military withstood a series of invasion attempts by leftist Dominican exiles. On June 19, 1949, an airplane carrying Dominican rebels from Guatemala was intercepted and destroyed by the Dominican coastguard at Luperón on the north coast. Ten years later, on June 14, 1959, Dominican revolutionaries launched three simultaneous attacks. At Estero Hondo and Maimón on the north coast, the rebels followed the Castro tactic of landing from ships, but the Dominican government's air power and artillery overwhelmed the attackers as they landed. At Constanza in the high mountains near the border with Haiti, a small band of armed exiles came by air. On that occasion, the heavy bombers of the Dominican Air Force came into action but were inaccurate, hitting more civilians than guerrillas. It was Dominican peasants who tracked down and captured or killed most of the fugitives, for which they received cash bounties from Trujillo's government.

Trujillo and his family established a near-monopoly over the national economy. By the time of his death, he had accumulated a fortune of around $800 million; he and his family owned 50–60% of the arable land, some 700,000 acres (2,800 km2), and Trujillo-owned businesses accounted for 80% of the commercial activity in the capital.[83] He exploited nationalist sentiment to purchase most of the nation's sugar plantations and refineries from U.S. corporations; operated monopolies on salt, rice, milk, cement, tobacco, coffee, and insurance; owned two large banks, several hotels, port facilities, an airline and shipping line; deducted 10% of all public employees' salaries (ostensibly for his party); and received a portion of prostitution revenues.[84] World War II brought increased demand for Dominican exports, and the 1940s and early 1950s witnessed economic growth and considerable expansion of the national infrastructure. During this period, the capital city was transformed from merely an administrative center to the national center of shipping and industry, although "it was hardly coincidental that new roads often led to Trujillo's plantations and factories, and new harbors benefited Trujillo's shipping and export enterprises."[85]

Mismanagement and corruption resulted in major economic problems. By the end of the 1950s, the economy was deteriorating because of a combination of overspending on a festival to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the regime, overspending to purchase privately owned sugar mills and electricity plants, and a decision to make a major investment in state sugar production that proved economically unsuccessful. In 1956, Trujillo's agents in New York murdered Jesús María de Galíndez, a Basque exile who had worked for Trujillo but who later denounced the Trujillo regime and caused public opinion in the United States to turn against Trujillo. In June 1960, Dominican secret police agents in Caracas used a car bomb in a nearly successful attempt to kill President Rómulo Betancourt of Venezuela, who had become the leading voice in the anti-Trujillo chorus, burning him badly. Tracing the attack to Trujillo, the Organization of American States (OAS) imposed sanctions for the first time since its creation in 1946, cutting off shipments of oil, among other things, to the Dominican Republic. Refusing to back down, Trujillo lashed out at Catholic priests who read a pastoral letter from the pulpit asking for merciful treatment of political opponents. One of his last-ditch threats was to ally with the Soviet Union, as he had implied was an option in the past.

A group of Dominican dissidents killed Trujillo in a car chase on the way to his country villa near San Cristóbal on May 30, 1961. The sanctions remained in force after Trujillo's assassination. His son Ramfis took over the presidency and rounded up all the conspirators. They were summarily executed, some of them being fed to sharks.[86] In November 1961, the military plot of the Rebellion of the Pilots forced the Trujillo family into exile, fleeing to France, and the heretofore puppet-president Joaquín Balaguer assumed effective power.

The post-Trujillo instability 1961–1965

At the insistence of the United States, Balaguer was forced to share power with a seven-member Council of State, established on January 1, 1962, and including moderate members of the opposition. OAS sanctions were lifted January 4, and, after an attempted coup, Balaguer resigned and went into exile on January 16. The reorganized Council of State, under President Rafael Filiberto Bonnelly headed the Dominican government until elections could be held. These elections, in December 1962, were won by Juan Bosch, a scholar and poet who had founded the opposition Partido Revolucionario Dominicano (Dominican Revolutionary Party, or PRD) in exile, during the Trujillo years. His leftist policies, including land redistribution, nationalization of certain foreign holdings, and attempts to bring the military under civilian control, antagonized the military officer corps, the Catholic hierarchy, and the upper-class, who feared "another Cuba".

The Presidency of Juan Bosch in 1963 led to one of the tensest periods in contemporary Haitian-Dominican relations. Bosch supported the efforts of Haitian exiles who trained to overthrow François Duvalier, Haiti's repressive president. In April 1963, former Haitian army officers reportedly tried to kill Duvalier's children, and many of those accused took refuge in the embassies of Latin American countries in Port-au-Prince, the Haitian capital. When Haitian police raided the Dominican embassy and held captive 22 refugees, the Dominican Republic broke off diplomatic relations and threatened to invade Haiti. The OAS mediated the dispute and eased the tension; Dominican troops, ready to invade, pulled back from the border; and many of the refugees were granted safe conduct out of Haiti. Hostilities erupted again in September that year when both sides shelled each other across the border. The OAS again intervened to make peace.

In September 1963 Bosch was overthrown by a right-wing military coup led by Colonel Elías Wessin and was replaced by a three-man military junta. Bosch went into exile to Puerto Rico. Afterwards, a supposedly civilian triumvirate established a de facto dictatorship.

Dominican Civil War and second United States occupation 1965–66

On April 16, 1965, growing dissatisfaction generated another military rebellion on April 24, 1965 that demanded Bosch's restoration. The insurgents, reformist officers and civilian combatants loyal to Bosch commanded by Colonel Francisco Caamaño, and who called themselves the Constitutionalists, staged a coup, seizing the national palace. Immediately, conservative military forces, led by Wessin and calling themselves Loyalists, struck back with tank assaults and aerial bombings against Santo Domingo. A few days of upheaval saw heavy fighting in the streets of the city and a pitched battle fought on the main bridge across the Ozama River, where civilians used guns supplied by their military allies to repulse the tank corps loyal to the military government, preventing it from entering the capital.

On April 28, these anti-Bosch army elements requested U.S. military intervention and U.S. forces landed, ostensibly to protect U.S. citizens and to evacuate U.S. and other foreign nationals. U.S. President Lyndon B. Johnson, convinced of the defeat of the Loyalist forces and fearing the creation of "a second Cuba"[87] on America's doorstep, ordered U.S. forces to restore order. In what was initially known as Operation Power Pack, 27,677 U.S. troops were ultimately ordered to the Dominican Republic.[88] The 4th Marine Expeditionary Force and the army's 82nd Airborne Division spearheaded the occupation. Psychological Warfare and Special Forces units also took part in the action.

Denied a military victory, the Constitutionalist rebels quickly had a Constitutionalist congress elect Caamaño president of the country. U.S. officials countered by backing General Antonio Imbert. On May 7, Imbert was sworn in as president of the Government of National Reconstruction. The next step in the stabilization process, as envisioned by Washington and the OAS, was to arrange an agreement between President Caamaño and President Imbert to form a provisional government committed to early elections. However, Caamaño refused to meet with Imbert until several of the Loyalist officers, including Wessin y Wessin, were made to leave the country. On 13 May General Imbert launched an eight-day offensive to eliminate rebel resistance north of the line of communications. During the attack, U.S. troops shot down one of the new government's five P-51 Mustangs when it accidentally strafed their position. Imbert's forces took the northern part of the capital, destroying many buildings and killing many black civilians.[Note 4] The United Nations dispatched a human rights team to investigate alleged atrocities.[89]