Hominidae

The Hominidae (/hɒˈmɪnɪdiː/), whose members are known as great apes[note 1] or hominids (/ˈhɒmɪnɪdz/), are a taxonomic family of primates that includes eight extant species in four genera: Pongo, the Bornean, Sumatran and Tapanuli orangutan; Gorilla, the eastern and western gorilla; Pan, the common chimpanzee and the bonobo; and Homo, of which only modern humans remain.[1]

| Hominidae[1] | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| The eight extant hominid species, one row per genus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Parvorder: | Catarrhini |

| Superfamily: | Hominoidea |

| Family: | Hominidae Gray, 1825[2] |

| Type genus | |

| Homo Linnaeus, 1758 | |

| Subfamilies | |

|

sister: Hylobatidae | |

| |

| Distribution of great ape species | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Several revisions in classifying the great apes have caused the use of the term "hominid" to vary over time. The original meaning of "hominid" referred only to humans (Homo) and their closest extinct relatives. However, by the 1990s both humans, apes, and their ancestors were considered to be "hominids". The earlier restrictive meaning has now been largely assumed by the term "hominin", which comprises all members of the human clade after the split from the chimpanzees (Pan). The current, 21st-century meaning of "hominid" includes all the great apes including humans. Usage still varies, however, and some scientists and laypersons still use "hominid" in the original restrictive sense; the scholarly literature generally shows the traditional usage until around the turn of the 21st century.[5]

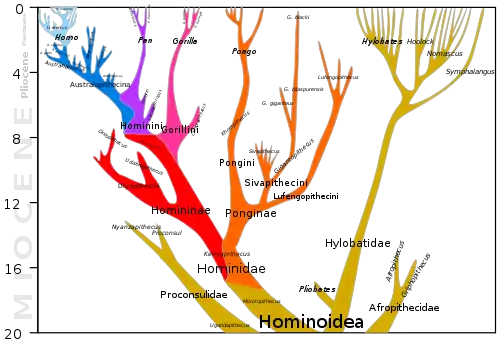

Within the taxon Hominidae, a number of extant and known extinct, that is, fossil, genera are grouped with the humans, chimpanzees, and gorillas in the subfamily Homininae; others with orangutans in the subfamily Ponginae (see classification graphic below). The most recent common ancestor of all Hominidae lived roughly 14 million years ago,[6] when the ancestors of the orangutans speciated from the ancestral line of the other three genera.[7] Those ancestors of the family Hominidae had already speciated from the family Hylobatidae (the gibbons), perhaps 15 to 20 million years ago.[7][8]

Due to the close genetic relationship between humans and the other great apes, certain animal rights organizations, such as the Great Ape Project, argue that nonhuman great apes are persons and should be given basic human rights. 29 countries have already instituted a research ban to protect great apes from any kind of scientific testing.[9]

Evolution

In the early Miocene, about 22 million years ago, there were many species of arboreally adapted primitive catarrhines from East Africa; the variety suggests a long history of prior diversification. Fossils at 20 million years ago include fragments attributed to Victoriapithecus, the earliest Old World monkey. Among the genera thought to be in the ape lineage leading up to 13 million years ago are Proconsul, Rangwapithecus, Dendropithecus, Limnopithecus, Nacholapithecus, Equatorius, Nyanzapithecus, Afropithecus, Heliopithecus, and Kenyapithecus, all from East Africa.

At sites far distant from East Africa, the presence of other generalized non-cercopithecids, that is, non-monkey primates, of middle Miocene age—Otavipithecus from cave deposits in Namibia, and Pierolapithecus and Dryopithecus from France, Spain and Austria—is further evidence of a wide diversity of ancestral ape forms across Africa and the Mediterranean basin during the relatively warm and equable climatic regimes of the early and middle Miocene. The most recent of these far-flung Miocene apes (hominoids) is Oreopithecus, from the fossil-rich coal beds in northern Italy and dated to 9 million years ago.

Molecular evidence indicates that the lineage of gibbons (family Hylobatidae), the lesser apes, diverged from that of the great apes some 18–12 million years ago, and that of orangutans (subfamily Ponginae) diverged from the other great apes at about 12 million years. There are no fossils that clearly document the ancestry of gibbons, which may have originated in a still-unknown South East Asian hominoid population; but fossil proto-orangutans, dated to around 10 million years ago, may be represented by Sivapithecus from India and Griphopithecus from Turkey.[10] Species close to the last common ancestor of gorillas, chimpanzees and humans may be represented by Nakalipithecus fossils found in Kenya and Ouranopithecus found in Greece. Molecular evidence suggests that between 8 and 4 million years ago, first the gorillas (genus Gorilla), and then the chimpanzees (genus Pan) split off from the line leading to the humans. Human DNA is approximately 98.4% identical to that of chimpanzees when comparing single nucleotide polymorphisms (see human evolutionary genetics).[11] The fossil record, however, of gorillas and chimpanzees is limited; both poor preservation—rain forest soils tend to be acidic and dissolve bone—and sampling bias probably contribute most to this problem.

Other hominins probably adapted to the drier environments outside the African equatorial belt; and there they encountered antelope, hyenas, elephants and other forms becoming adapted to surviving in the East African savannas, particularly the regions of the Sahel and the Serengeti. The wet equatorial belt contracted after about 8 million years ago, and there is very little fossil evidence for the divergence of the hominin lineage from that of gorillas and chimpanzees—which split was thought to have occurred around that time. The earliest fossils argued by some to belong to the human lineage are Sahelanthropus tchadensis (7 Ma) and Orrorin tugenensis (6 Ma), followed by Ardipithecus (5.5–4.4 Ma), with species Ar. kadabba and Ar. ramidus.

Taxonomy

Terminology

The classification of the great apes has been revised several times in the last few decades; these revisions have led to a varied use of the word "hominid" over time. The original meaning of the term referred to only humans and their closest relatives—what is now the modern meaning of the term "hominin". The meaning of the taxon Hominidae changed gradually, leading to a modern usage of "hominid" that includes all the great apes including humans.

A number of very similar words apply to related classifications:

- A hominoid, sometimes called an ape, is a member of the superfamily Hominoidea: extant members are the gibbons (lesser apes, family Hylobatidae) and the hominids.

- A hominid is a member of the family Hominidae, the great apes: orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees and humans.

- A hominine is a member of the subfamily Homininae: gorillas, chimpanzees, and humans (excludes orangutans).

- A hominin is a member of the tribe Hominini: chimpanzees and humans.[12]

- A homininan, following a suggestion by Wood and Richmond (2000), would be a member of the subtribe Hominina of the tribe Hominini: that is, modern humans and their closest relatives, including Australopithecina, but excluding chimpanzees.[13][14]

- A human is a member of the genus Homo, of which Homo sapiens is the only extant species, and within that Homo sapiens sapiens is the only surviving subspecies.

A cladogram indicating common names (cf. more detailed cladogram below):

| Hominoidea (hominoids, apes) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Extant and fossil relatives of humans

Hominidae was originally the name given to the family of humans and their (extinct) close relatives, with the other great apes (that is, the orangutans, gorillas and chimpanzees) all being placed in a separate family, the Pongidae. However, that definition eventually made Pongidae paraphyletic because at least one great ape species (the chimpanzees) proved to be more closely related to humans than to other great apes. Most taxonomists today encourage monophyletic groups—this would require, in this case, the use of Pongidae to be restricted to just one closely related grouping. Thus, many biologists now assign Pongo (as the subfamily Ponginae) to the family Hominidae. The taxonomy shown here follows the monophyletic groupings according to the modern understanding of human and great ape relationships.

Humans and close relatives including the tribes Hominini and Gorillini form the subfamily Homininae (see classification graphic below). (A few researchers go so far as to refer the chimpanzees and the gorillas to the genus Homo along with humans.)[15][16][17] But, it is those fossil relatives more closely related to humans than the chimpanzees that represent the especially close members of the human family, and without necessarily assigning subfamily or tribal categories.[18]

Many extinct hominids have been studied to help understand the relationship between modern humans and the other extant hominids. Some of the extinct members of this family include Gigantopithecus, Orrorin, Ardipithecus, Kenyanthropus, and the australopithecines Australopithecus and Paranthropus.[19]

The exact criteria for membership in the tribe Hominini under the current understanding of human origins are not clear, but the taxon generally includes those species that share more than 97% of their DNA with the modern human genome, and exhibit a capacity for language or for simple cultures beyond their 'local family' or band. The theory of mind concept—including such faculties as empathy, attribution of mental state, and even empathetic deception—is a controversial criterion; it distinguishes the adult human alone among the hominids. Humans acquire this capacity after about four years of age, whereas it has not been proven (nor has it been disproven) that gorillas or chimpanzees ever develop a theory of mind.[20] This is also the case for some New World monkeys outside the family of great apes, as, for example, the capuchin monkeys.

However, even without the ability to test whether early members of the Hominini (such as Homo erectus, Homo neanderthalensis, or even the australopithecines) had a theory of mind, it is difficult to ignore similarities seen in their living cousins. Orangutans have shown the development of culture comparable to that of chimpanzees,[21] and some say the orangutan may also satisfy those criteria for the theory of mind concept. These scientific debates take on political significance for advocates of great ape personhood.

Phylogeny

Below is a cladogram with extinct species.[22][23][24] It is indicated approximately how many million years ago (Mya) the clades diverged into newer clades.[25]

| Hominidae (18) |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Taxonomy of Hominoidea (emphasis on family Hominidae): after an initial separation from the main line by the Hylobatidae (gibbons) some 18 million years ago, the line of Ponginae broke away, leading to the orangutan; later, the Homininae split into the tribes Hominini (led to humans and chimpanzees) and Gorillini (led to gorillas).

Extant

There are eight living species of great ape which are classified in four genera. The following classification is commonly accepted:[1]

- Family Hominidae: humans and other great apes; extinct genera and species excluded[1]

- Subfamily Ponginae

- Tribe Pongini

- Genus Pongo

- Bornean orangutan, Pongo pygmaeus

- Pongo pygmaeus pygmaeus

- Pongo pygmaeus morio

- Pongo pygmaeus wurmbii

- Sumatran orangutan, Pongo abelii

- Tapanuli orangutan, Pongo tapanuliensis[26]

- Bornean orangutan, Pongo pygmaeus

- Genus Pongo

- Tribe Pongini

- Subfamily Homininae

- Tribe Gorillini

- Genus Gorilla

- Western gorilla, Gorilla gorilla

- Western lowland gorilla, Gorilla gorilla gorilla

- Cross River gorilla, Gorilla gorilla diehli

- Eastern gorilla, Gorilla beringei

- Mountain gorilla, Gorilla beringei beringei

- Eastern lowland gorilla, Gorilla beringei graueri

- Western gorilla, Gorilla gorilla

- Genus Gorilla

- Tribe Hominini

- Subtribe Panina

- Genus Pan

- Common chimpanzee (common chimpanzee), Pan troglodytes

- Central chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes troglodytes

- Western chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes verus

- Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes ellioti

- Eastern chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii

- Bonobo (pygmy chimpanzee), Pan paniscus

- Common chimpanzee (common chimpanzee), Pan troglodytes

- Genus Pan

- Subtribe Hominina

- Genus Homo

- Human, Homo sapiens

- Anatomically modern human, Homo sapiens sapiens

- Human, Homo sapiens

- Genus Homo

- Subtribe Panina

- Tribe Gorillini

- Subfamily Ponginae

Fossil

In addition to the extant species and subspecies, archaeologists, paleontologists, and anthropologists have discovered and classified numerous extinct great ape species as below, based on the taxonomy shown.[27]

Family Hominidae

- Subfamily Ponginae[28]

- Tribe Lufengpithecini †

- Lufengpithecus

- Lufengpithecus lufengensis

- Lufengpithecus keiyuanensis

- Lufengpithecus hudienensis

- Lufengpithecus

- Tribe Sivapithecini†

- Ankarapithecus

- Ankarapithecus meteai

- Sivapithecus

- Sivapithecus brevirostris

- Sivapithecus punjabicus

- Sivapithecus parvada

- Sivapithecus sivalensis

- Sivapithecus indicus

- Gigantopithecus

- Gigantopithecus bilaspurensis

- Gigantopithecus blacki

- Gigantopithecus giganteus

- Ankarapithecus

- Tribe Pongini

- Tribe Lufengpithecini †

- Subfamily Homininae[29][30]

- Tribe Dryopithecini †

- Kenyapithecus

- Kenyapithecus wickeri

- Danuvius

- Danuvius guggenmosi

- Pierolapithecus

- Pierolapithecus catalaunicus

- Udabnopithecus

- Udabnopithecus garedziensis

- Ouranopithecus

- Ouranopithecus macedoniensis

- Otavipithecus

- Otavipithecus namibiensis

- Morotopithecus (placement disputed)

- Morotopithecus bishopi

- Oreopithecus (placement disputed)

- Oreopithecus bambolii

- Nakalipithecus

- Nakalipithecus nakayamai

- Anoiapithecus

- Anoiapithecus brevirostris

- Hispanopithecus

- Hispanopithecus laietanus

- Hispanopithecus crusafonti

- Dryopithecus

- Dryopithecus wuduensis

- Dryopithecus fontani

- Dryopithecus brancoi

- Dryopithecus laietanus

- Dryopithecus crusafonti

- Rudapithecus

- Rudapithecus hungaricus

- Samburupithecus

- Samburupithecus kiptalami

- Kenyapithecus

- Tribe Gorillini

- Chororapithecus † (placement debated)

- Chororapithecus abyssinicus

- Chororapithecus † (placement debated)

- Tribe Hominini

- Subtribe Panina

- Subtribe Hominina

- Graecopithecus †[31]

- Graecopithecus freybergi

- Sahelanthropus†

- Sahelanthropus tchadensis

- Orrorin†

- Orrorin tugenensis

- Ardipithecus†

- Kenyanthropus†

- Kenyanthropus platyops

- Praeanthropus†[32]

- Australopithecus†

- Paranthropus†

- Homo – close relatives of modern humans

- Homo gautengensis†

- Homo rudolfensis†

- Homo naledi†

- Homo habilis†

- Homo georgicus† (thought by some to be an early subspecies of Homo erectus)

- Homo floresiensis†

- Homo erectus†

- Homo ergaster† (considered by some to be an early subspecies of Homo erectus)

- Homo antecessor†

- Homo heidelbergensis† (sometimes called Archaic Homo sapiens)

- Homo cepranensis†

- Homo helmei†

- Homo palaeojavanicus†

- Homo tsaichangensis†

- Denisovans (scientific name not yet assigned)†

- Homo neanderthalensis† (sometimes called Homo sapiens neanderthalensis)

- Homo rhodesiensis†

- Homo sapiens

- Homo sapiens idaltu†

- Archaic Homo sapiens†

- Red Deer Cave people † (scientific name has not yet been assigned; perhaps a race of modern humans or a hybrid[33] of modern humans and Denisovans[34])

- Graecopithecus †[31]

- Tribe Dryopithecini †

Physical description

The great apes are tailless primates, with the smallest living species being the bonobo at 30–40 kilograms in weight, and the largest being the eastern gorillas, with males weighing 140–180 kilograms. In all great apes, the males are, on average, larger and stronger than the females, although the degree of sexual dimorphism varies greatly among species. Although most living species are predominantly quadrupedal, they are all able to use their hands for gathering food or nesting materials, and, in some cases, for tool use.[35]

Most species are omnivorous,[36] but chimpanzees and orangutans primarily eat fruit. When gorillas run short of fruit at certain times of the year or in certain regions, they resort to eating shoots and leaves, often of bamboo, a type of grass. Gorillas have extreme adaptations for chewing and digesting such low-quality forage, but they still prefer fruit when it is available, often going miles out of their way to find especially preferred fruits. Humans, since the neolithic revolution, consume mostly cereals and other starchy foods, including increasingly highly processed foods, as well as many other domesticated plants (including fruits) and meat. Hominid teeth are similar to those of the Old World monkeys and gibbons, although they are especially large in gorillas. The dental formula is 2.1.2.32.1.2.3. Human teeth and jaws are markedly smaller for their size than those of other apes, which may be an adaptation to not only having supplanted with extensive tool use the role of jaws in hunting and fighting, but also eating cooked food since the end of the Pleistocene.[37][38]

Gestation in great apes lasts 8–9 months, and results in the birth of a single offspring, or, rarely, twins. The young are born helpless, and require care for long periods of time. Compared with most other mammals, great apes have a remarkably long adolescence, not being weaned for several years, and not becoming fully mature for eight to thirteen years in most species (longer in orangutans and humans). As a result, females typically give birth only once every few years. There is no distinct breeding season.[35]

The gorillas and the chimpanzee live in family groups of around five to ten individuals, although much larger groups are sometimes noted. Chimpanzees live in larger groups that break up into smaller groups when fruit becomes less available. When small groups of female chimpanzees go off in separate directions to forage for fruit, the dominant males can no longer control them and the females often mate with other subordinate males. In contrast, groups of gorillas stay together regardless of the availability of fruit. When fruit is hard to find, they resort to eating leaves and shoots. Because gorilla groups stay together, the male is able to monopolize the females in his group. This fact is related to gorillas' greater sexual dimorphism relative to that of chimpanzees; that is, the difference in size between male and female gorillas is much greater than that between male and female chimpanzees. This enables gorilla males to physically dominate female gorillas more easily. In both chimpanzees and gorillas, the groups include at least one dominant male, and young males leave the group at maturity.

Legal status

Due to the close genetic relationship between humans and the other great apes, certain animal rights organizations, such as the Great Ape Project, argue that nonhuman great apes are persons and should be given basic human rights. In 1999, New Zealand was the first country to ban any great ape experimentation, and now 29 countries have currently instituted a research ban to protect great apes from any kind of scientific testing.

On 25 June 2008, the Spanish parliament supported a new law that would make "keeping apes for circuses, television commercials or filming" illegal.[39] On 8 September 2010, the European Union banned the testing of great apes.[40]

Conservation

The following table lists the estimated number of great ape individuals living outside zoos.

| Species | Estimated number |

Conservation status |

Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bornean orangutan | 61,234 | Critically endangered | [41] |

| Sumatran orangutan | 6,667 | Critically endangered | [42] |

| Tapanuli orangutan | 800 | Critically endangered | [43] |

| Western gorilla | 200,000 | Critically endangered | [44] |

| Eastern gorilla | 6,000 | Critically endangered | [44] |

| Chimpanzee | 100,000 | Endangered | [45] |

| Bonobo | 10,000 | Endangered | [45] |

| Human | 7,812,102,600 | Least concern | [46] |

See also

- Bili ape

- Dawn of Humanity (2015 PBS film)

- Great ape language

- Great ape research ban

- Great Apes Survival Partnership

- Kinshasa Declaration on Great Apes

- List of human evolution fossils

- List of individual apes

- Oldest hominids

- Prehistoric Autopsy (2012 BBC documentary)

- Primate cognition

- The Mind of an Ape

- Timeline of human evolution

Notes

- "Great ape" is a common name rather than a taxonomic label, and there are differences in usage, even by the same author. The term may or may not include humans, as when Dawkins writes "Long before people thought in terms of evolution ... great apes were often confused with humans"[3] and "gibbons are faithfully monogamous, unlike the great apes which are our closer relatives."[4]

References

- Groves, C. P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 181–184. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- Gray, J. E. (1825). "An outline of an attempt at the disposition of Mammalia into Tribes and Families, with a list of genera apparently appertaining to each Tribe". Annals of Philosophy, new series. 10: 337–334.

- Dawkins, R. (2005). The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Life (p/b ed.). London, England: Phoenix (Orion Books). p. 114. ISBN 978-0-7538-1996-8.

- Dawkins (2005), p. 126.

- Morton, Mary. "Hominid vs. hominin". Earth Magazine. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- Andrew Hill; Steven Ward (1988). "Origin of the Hominidae: The Record of African Large Hominoid Evolution Between 14 My and 4 My". Yearbook of Physical Anthropology. 31 (59): 49–83. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330310505.

- Dawkins R (2004) The Ancestor's Tale.

- "Query: Hominidae/Hylobatidae". TimeTree. Temple University. 2015. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- "International Bans | Laws | Release & Restitution for Chimpanzees". releasechimps.org. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- Srivastava (2009). Morphology of the Primates And Human Evolution. PHI Learning Pvt. Ltd. p. 87. ISBN 978-81-203-3656-8. Retrieved 6 November 2011.

- Chen, Feng-Chi; Li, Wen-Hsiung (15 January 2001). "Genomic Divergences between Humans and Other Hominoids and the Effective Population Size of the Common Ancestor of Humans and Chimpanzees". American Journal of Human Genetics. 68 (2): 444–456. doi:10.1086/318206. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 1235277. PMID 11170892.

- B. Wood (2010). "Reconstructing human evolution: Achievements, challenges, and opportunities". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 107: 8902–8909. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.8902W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1001649107. PMC 3024019. PMID 20445105.

- Wood; Richmond, B. G. (2000). "Human evolution: taxonomy and paleobiology". Journal of Anatomy. 197 (Pt 1): 19–60. doi:10.1046/j.1469-7580.2000.19710019.x. PMC 1468107. PMID 10999270.. In this suggestion, the new subtribe of Hominina was to be designated as including the genus Homo exclusively, so that Hominini would have two subtribes, Australopithecina and Hominina, with the only known genus in Hominina being Homo. Orrorin (2001) has been proposed as a possible ancestor of Hominina but not Australopithecina.Reynolds, Sally C.; Gallagher, Andrew (29 March 2012). African Genesis: Perspectives on Hominin Evolution. ISBN 9781107019959.. Designations alternative to Hominina have been proposed: Australopithecinae (Gregory & Hellman 1939) and Preanthropinae (Cela-Conde & Altaba 2002); Brunet, M.; et al. (2002). "A new hominid from the upper Miocene of Chad, central Africa". Nature. 418 (6894): 145–151. Bibcode:2002Natur.418..145B. doi:10.1038/nature00879. PMID 12110880. S2CID 1316969. Cela-Conde, C.J.; Ayala, F.J. (2003). "Genera of the human lineage". PNAS. 100 (13): 7684–7689. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.7684C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0832372100. PMC 164648. PMID 12794185. Wood, B.; Lonergan, N. (2008). "The hominin fossil record: taxa, grades and clades" (PDF). J. Anat. 212 (4): 354–376. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.00871.x. PMC 2409102. PMID 18380861.

- "GEOL 204 The Fossil Record: The Scatterlings of Africa: The Origins of Humanity". www.geol.umd.edu. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- Pickrell, John (20 May 2003). "Chimps Belong on Human Branch of Family Tree, Study Says". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- Relationship Humans-Gorillas Archived 30 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- Watson, E. E.; et al. (2001). "Homo genus: a review of the classification of humans and the great apes". In Tobias, P. V.; et al. (eds.). Humanity from African Naissance to Coming Millennia. Florence: Firenze Univ. Press. pp. 311–323.

- Schwartz, J.H. (1986) Primate systematics and a classification of the order. Comparative primate biology volume 1: Systematics, evolution, and anatomy (ed. by D.R. Swindler, and J. Erwin), pp. 1–41, Alan R. Liss, New York.

- Schwartz, J.H. (2004b) Issues in hominid systematics. Zona Arqueología 4, 360–371.

- Heyes, C. M. (1998). "Theory of Mind in Nonhuman Primates" (PDF). Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 21 (1): 101–14. doi:10.1017/S0140525X98000703. PMID 10097012. bbs00000546.

- Van Schaik C.P.; Ancrenaz, M; Borgen, G; Galdikas, B; Knott, CD; Singleton, I; Suzuki, A; Utami, SS; Merrill, M (2003). "Orangutan cultures and the evolution of material culture". Science. 299 (5603): 102–105. Bibcode:2003Sci...299..102V. doi:10.1126/science.1078004. PMID 12511649. S2CID 25139547.

- Grabowski, Mark; Jungers, William L. (2017). "Evidence of a chimpanzee-sized ancestor of humans but a gibbon-sized ancestor of apes". Nature Communications. 8 (1): 880. Bibcode:2017NatCo...8..880G. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00997-4. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 5638852. PMID 29026075.

- Nengo, Isaiah; Tafforeau, Paul; Gilbert, Christopher C.; Fleagle, John G.; Miller, Ellen R.; Feibel, Craig; Fox, David L.; Feinberg, Josh; Pugh, Kelsey D. (2017). "New infant cranium from the African Miocene sheds light on ape evolution". Nature. 548 (7666): 169–174. Bibcode:2017Natur.548..169N. doi:10.1038/nature23456. PMID 28796200. S2CID 4397839.

- "Hominidae | primate family". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- Malukiewicz, Joanna; Hepp, Crystal M.; Guschanski, Katerina; Stone, Anne C. (1 January 2017). "Phylogeny of the jacchus group of Callithrix marmosets based on complete mitochondrial genomes". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 162 (1): 157–169. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23105. ISSN 1096-8644. PMID 27762445. Fig 2: "Divergence time estimates for the jacchus marmoset group based on the BEAST4 (Di Fiore et al., 2015) calibration scheme for alignment A.[...] Numbers at each node indicate the median divergence time estimate."

- Nater, Alexander; Mattle-Greminger, Maja P.; Nurcahyo, Anton; et al. (2 November 2017). "Morphometric, Behavioral, and Genomic Evidence for a New Orangutan Species". Current Biology. 27 (22): 3487–3498.e10. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.09.047. PMID 29103940.

- Haaramo, Mikko (14 January 2005). "Hominoidea". Mikko's Phylogeny Archive.

- Haaramo, Mikko (4 February 2004). "Pongidae". Mikko's Phylogeny Archive.

- Haaramo, Mikko (14 January 2005). "Hominoidea". Mikko's Phylogeny Archive.

- Haaramo, Mikko (10 November 2007). "Hominidae". Mikko's Phylogeny Archive.

- Fuss, J; Spassov, N; Begun, DR; Böhme, M (2017). "Potential hominin affinities of Graecopithecus from the Late Miocene of Europe". PLOS ONE. 12 (5): 5. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1277127F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0177127. PMC 5439669. PMID 28531170.

- Paleodb

- Barras, Colin (14 March 2012). "Chinese human fossils unlike any known species". New Scientist. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- "National Geographic". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- Harcourt, A.H., MacKinnon, J. & Wrangham, R.W. (1984). Macdonald, D. (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. pp. 422–439. ISBN 978-0-87196-871-5.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- May 2015, Alina Bradford-Live Science Contributor 29. "Facts About Apes". livescience.com. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- Brace, C. Loring; Mahler, Paul Emil (1971). "Post-Pleistocene changes in the human dentition" (PDF). American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 34 (2): 191–203. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330340205. hdl:2027.42/37509. PMID 5572603.

- Wrangham, Richard (2007). "Chapter 12: The Cooking Enigma". In Charles Pasternak (ed.). What Makes Us Human?. Oxford: Oneworld Press. ISBN 978-1-85168-519-6.

- "Spanish parliament to extend rights to apes". Reuters. 25 June 2008. Retrieved 11 July 2008.

- "New EU rules on animal testing ban use of apes". 12 September 2010.

- "Orangutan Action Plan 2007–2017" (PDF) (in Indonesian). Government of Indonesia. 2007. p. 5. Retrieved 1 May 2010.\

- An estimate of the number of wild orangutans in 2004: "Orangutan Action Plan 2007–2017" (PDF). Government of Indonesia. 2007.

- Davis, Nicola (2 November 2017). "New species of orangutan discovered in Sumatra – and is already endangered". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- "Gorillas on Thin Ice". United Nations Environment Programme. 15 January 2009. Archived from the original on 18 May 2016. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- Vigilant, Linda (2004). "Chimpanzees". Current Biology. 14 (10): R369–R371. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.05.006. PMID 15186757.

- "U.S. and World Population Clock". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 29 November 2018.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hominidae. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Hominidae. |

| The Wikibook Dichotomous Key has a page on the topic of: Hominidae |

- The Animal Legal and Historical Center at Michigan State University College of Law, Great Apes and the Law

- Renderings of Hominid Exemplars at the Smithsonian

- Additional information on great apes

- NPR News: Toumaï the Human Ancestor

- Hominid Species at TalkOrigins Archive

- For more details on Hominid species, including excellent photos of fossil hominids

- New Scientist 19 May 2003 – Chimps are human, gene study implies

- Scientific American magazine (April 2006 Issue) Why Are Some Animals So Smart?

- A new mediterranean hominoid-hominid link discovered, Anoiapithecus brevirostris, "Lluc": A unique Middle Miocene European hominoid and the origins of the great ape and human clade Link to graphical reconstruction

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).