Homininae

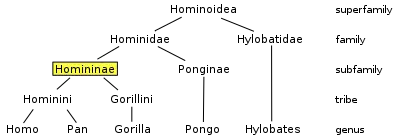

Homininae (/hɒmɪˈnaɪniː/), also called "African hominids" or "African apes", is a subfamily of Hominidae.[1][2] It includes two tribes, with their extant as well as extinct species: 1) the tribe Hominini (with the genus Homo including modern humans and numerous extinct species; the subtribe Australopithecina, comprising at least two extinct genera; and the subtribe Panina, represented only by the genus Pan, which includes chimpanzees and bonobos)―and 2) the tribe Gorillini (gorillas). Alternatively, the genus Pan is sometimes considered to belong to its own third tribe, Panini. Homininae comprises all hominids that arose after orangutans (subfamily Ponginae) split from the line of great apes. The Homininae cladogram has three main branches, which lead to gorillas (through the tribe Gorillini), and to humans and chimpanzees via the tribe Hominini and subtribes Hominina and Panina (see the evolutionary tree below). There are two living species of Panina (chimpanzees and bonobos) and two living species of gorillas, but only one extant human species. Traces of extinct Homo species, including Homo floresiensis and Homo denisova, have been found with dates as recent as 40,000 years ago. Organisms in this subfamily are described as hominine or hominines (not to be confused with the terms hominins or hominini).

| Homininae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Three hominines: a human holding a young gorilla and a young chimpanzee. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae Gray, 1825 |

| Type species | |

| Homo sapiens Linnaeus, 1758 | |

| Tribe | |

|

†Dryopithecini | |

History of discoveries and classification

Until 1970, the family (and term) Hominidae meant humans only; the non-human great apes were assigned to the family Pongidae.[3] Later discoveries led to revised classifications, with the great apes then united with humans (now in subfamily Homininae) as members of family Hominidae [4] By 1990, it was recognized that gorillas and chimpanzees are more closely related to humans than they are to orangutans, leading to their (gorillas and chimpanzees) placement in subfamily Homininae as well.[5]

The subfamily Homininae can be further subdivided into three branches: the tribe Gorillini (gorillas), the tribe Hominini with subtribes Panina (chimpanzees) and Hominina (humans and their extinct relatives), and the extinct tribe Dryopithecini. The Late Miocene fossil Nakalipithecus nakayamai, described in 2007, is a basal member of this clade, as is, perhaps, its contemporary Ouranopithecus; that is, they are not assignable to any of the three extant branches. Their existence suggests that the Homininae tribes diverged not earlier than about 8 million years ago (see Human evolutionary genetics).

Today, chimpanzees and gorillas live in tropical forests with acid soils that rarely preserve fossils. Although no fossil gorillas have been reported, four chimpanzee teeth about 500,000 years old have been discovered in the East-African rift valley (Kapthurin Formation, Kenya), where many fossils from the human lineage (hominins)[Note 1] have been found.[6] This shows that some chimpanzees lived close to Homo (H. erectus or H. rhodesiensis) at the time; the same is likely true for gorillas.

Taxonomic classification

| Hominoidea (hominoids, apes) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Homininae

- Tribe Dryopithecini†

- Kenyapithecus

- Kenyapitheus wickeri

- Ouranopithecus

- Ouranopithecus macedoniensis

- Otavipithecus

- Otavipithecus namibiensis

- Morotopithecus

- Morotopithecus bishopi

- Oreopithecus

- Oreopithecus bambolii

- Nakalipithecus

- Nakalipithecus nakayamai

- Anoiapithecus

- Anoiapithecus brevirostris

- Dryopithecus

- Dryopithecus wuduensis

- Dryopithecus fontani

- Hispanopithecus

- Hispanopithecus laietanus

- Hispanopithecus crusafonti

- Neopithecus

- Neopithecus brancoi

- Pierolapithecus

- Pierolapithecus catalaunicus

- Rudapithecus

- Rudapithecus hungaricus

- Samburupithecus

- Samburupithecus kiptalami

- Udabnopithecus

- Udabnopithecus garedziensis

- Danuvius

- Danuvius guggenmosi

- Kenyapithecus

- Tribe Gorillini

- Chororapithecus †

- Chororapithecus abyssinicus

- Genus Gorilla

- Western gorilla, Gorilla gorilla

- Western lowland gorilla, Gorilla gorilla gorilla

- Cross River gorilla, Gorilla gorilla diehli

- Eastern gorilla, Gorilla beringei

- Mountain gorilla, Gorilla beringei beringei

- Eastern lowland gorilla, Gorilla beringei graueri

- Western gorilla, Gorilla gorilla

- Chororapithecus †

- Tribe Hominini

- Subtribe Panina

- Genus Pan

- Chimpanzee (common chimpanzee), Pan troglodytes

- Central chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes troglodytes

- Western chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes verus

- Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes ellioti

- Eastern chimpanzee, Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii

- Bonobo (pygmy chimpanzee), Pan paniscus

- Chimpanzee (common chimpanzee), Pan troglodytes

- Genus Pan

- Subtribe Hominina

- Graecopithecus †

- Graecopithecus freybergi.[7] Note: Graecopithecus has also been subsumed by other authors into Dryopithecus. The placement of Graecopithecus within the Hominina, as shown here, represents a hypothesis, but not scientific consensus.

- Sahelanthropus†

- Sahelanthropus tchadensis

- Orrorin†

- Orrorin tugenensis

- Ardipithecus†

- Kenyanthropus†

- Kenyanthropus platyops

- Praeanthropus†[8]

- Australopithecus†

- Paranthropus†

- Homo – immediate ancestors of modern humans

- Homo gautengensis†

- Homo rudolfensis†

- Homo habilis†

- Homo floresiensis†

- Homo erectus†

- Homo ergaster†

- Homo antecessor†

- Homo heidelbergensis†

- Homo cepranensis†

- Denisovans (scientific name has not yet been assigned)†

- Homo neanderthalensis†

- Homo rhodesiensis†

- Homo sapiens

- Anatomically modern human, Homo sapiens sapiens

- Homo sapiens idaltu†

- Archaic Homo sapiens (Cro-magnon)†

- Red Deer Cave people† (scientific name has not yet been assigned; perhaps a race of modern humans or a hybrid[9] of modern humans and Denisovans[10])

- Graecopithecus †

- Subtribe Panina

Evolution

The age of the subfamily Homininae (of the Homininae–Ponginae last common ancestor) is estimated at some 14[11] to 12.5 million years (Sivapithecus).[12][13] Its separation into Gorillini and Hominini (the "gorilla–human last common ancestor", GHLCA) is estimated to have occurred at about 8 to 10 million years ago (TGHLCA) during the late Miocene, close to the age of Nakalipithecus nakayamai.[14]

There is evidence there was interbreeding of Gorillas and the Pan–Homo ancestors until right up to the Pan–Homo split.[15]

Evolution of bipedalism

Recent studies of Ardipithecus ramidus (4.4 million years old) and Orrorin tugenensis (6 million years old) suggest some degree of bipedalism. Australopithecus and early Paranthropus may have been bipedal. Very early hominins such as Ardipithecus ramidus may have possessed an arboreal type of bipedalism.[16]

Brain size evolution

There has been a gradual increase in brain volume (brain size) as the ancestors of modern humans progressed along the timeline of human evolution, starting from about 600 cm3 in Homo habilis up to 1500 cm3 in Homo neanderthalensis. However, modern Homo sapiens have a brain volume slightly smaller (1250 cm3) than Neanderthals, women have a brain slightly smaller than men and the Flores hominids (Homo floresiensis), nicknamed hobbits, had a cranial capacity of about 380 cm3 (considered small for a chimpanzee), about a third of the Homo erectus average. It is proposed that they evolved from H. erectus as a case of insular dwarfism. In spite of their smaller brain, there is evidence that H. floresiensis used fire and made stone tools at least as sophisticated as those of their proposed ancestors H. erectus.[17] In this case, it seems that for intelligence, the structure of the brain is more important than its size.[18]

Evolution of family structure and sexuality

Sexuality is related to family structure and partly shapes it. The involvement of fathers in education is quite unique to humans, at least when compared to other Homininae. Concealed ovulation and menopause in women both also occur in a few other primates however, but are uncommon in other species. Testis and penis size seems to be related to family structure: monogamy or promiscuity, or harem, in humans, chimpanzees or gorillas, respectively.[19][20] The levels of sexual dimorphism are generally seen as a marker of sexual selection. Studies have suggested that the earliest hominins were dimorphic and that this lessened over the course of the evolution of the genus Homo, correlating with humans becoming more monogamous, whereas gorillas, who live in harems, show a large degree of sexual dimorphism. Concealed (or "hidden") ovulation means that the phase of fertility is not detectable in women, whereas chimpanzees advertise ovulation via an obvious swelling of the genitals. Women can be partly aware of their ovulation along the menstrual phases, but men are essentially unable to detect ovulation in women. Most primates have semi-concealed ovulation, thus one can think that the common ancestor had semi-concealed ovulation, that was inherited by gorillas, and that later evolved in concealed ovulation in humans and advertised ovulation in chimpanzees. Menopause also occurs in rhesus monkeys, and possibly in chimpanzees, but does not in gorillas and is quite uncommon in other primates (and other mammal groups).[20]

See also

Notes

- A hominin is a member of the tribe Hominini, a hominine is a member of the subfamily Homininae, a hominid is a member of the family Hominidae, and a hominoid is a member of the superfamily Hominoidea.

Citations

- Grabowski M, Jungers WL (October 2017). "Evidence of a chimpanzee-sized ancestor of humans but a gibbon-sized ancestor of apes". Nature Communications. 8 (1): 880. doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00997-4. PMC 5638852. PMID 29026075.

- Fuss J, Spassov N, Begun DR, Böhme M (2017-05-22). "Potential hominin affinities of Graecopithecus from the Late Miocene of Europe". PLOS ONE. 12 (5): e0177127. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0177127. PMC 5439669. PMID 28531170.

- Goodman M (1964). "Man's place in the phylogeny of the primates as reflected in serum proteins". In Washburn SL (ed.). Classification and Human Evolution. Transaction Publishers. pp. 204–234. ISBN 978-0-202-36487-2.

- Goodman M (1974). "Biochemical Evidence on Hominid Phylogeny". Annual Review of Anthropology. 3: 203–228. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.03.100174.001223.

- Goodman M, Tagle DA, Fitch DH, Bailey W, Czelusniak J, Koop BF, Benson P, Slightom JL (March 1990). "Primate evolution at the DNA level and a classification of hominoids". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 30 (3): 260–6. doi:10.1007/BF02099995. PMID 2109087.

- McBrearty S, Jablonski NG (September 2005). "First fossil chimpanzee". Nature. 437 (7055): 105–8. doi:10.1038/nature04008. PMID 16136135.

- Fuss, J; Spassov, N; Begun, DR; Böhme, M (2017). "Potential hominin affinities of Graecopithecus from the Late Miocene of Europe". PLOS One. 12 (5).

- "Praeanthropus garhi Asfaw 1999 (ape)". Paleobiology Database. Fossilworks.

- Barras C (2012-03-14). "Chinese human fossils unlike any known species". New Scientist. Retrieved 2012-03-15.

- "Orangutan Pongo pygmaeus". Animals. National Geographic Society. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- Hill A, Ward S (1988). "Origin of the Hominidae: The Record of African Large Hominoid Evolution Between 14 My and 4 My". Yearbook of Physical Anthropology. 31 (59): 49–83. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330310505.

- Finarelli JA, Clyde WC (2004). "Reassessing hominoid phylogeny: Evaluating congruence in the morphological and temporal data" (PDF). Paleobiology. 30 (4): 614–651. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2004)030<0614:RHPECI>2.0.CO;2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-07-21. Retrieved 2017-12-04.

- Chaimanee Y, Suteethorn V, Jintasakul P, Vidthayanon C, Marandat B, Jaeger JJ (January 2004). "A new orang-utan relative from the Late Miocene of Thailand" (PDF). Nature. 427 (6973): 439–41. doi:10.1038/nature02245. PMID 14749830.

- Jha A (March 7, 2012). "Gorilla genome analysis reveals new human links". The Guardian. Retrieved May 8, 2015. Jha A (March 9, 2012). "Scientists unlock genetic code for gorillas - and show the human link". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved May 8, 2015. Hansford, Dave (November 13, 2007). "New Ape May Be Human-Gorilla Ancestor". National Geographic News. Retrieved May 8, 2015.

- Popadin, Konstantin; Gunbin, Konstantin; Peshkin, Leonid; Annis, Sofia; Fleischmann, Zoe; Kraytsberg, Genya; Markuzon, Natalya; Ackermann, Rebecca R.; Khrapko, Konstantin (2017-10-19). "Mitochondrial pseudogenes suggest repeated inter-species hybridization in hominid evolution". bioRxiv: 134502. doi:10.1101/134502.

- Kivell TL, Schmitt D (August 2009). "Independent evolution of knuckle-walking in African apes shows that humans did not evolve from a knuckle-walking ancestor". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 106 (34): 14241–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.0901280106. PMC 2732797. PMID 19667206.

- Brown P, Sutikna T, Morwood MJ, Soejono RP, Saptomo EW, Due RA (October 2004). "A new small-bodied hominin from the Late Pleistocene of Flores, Indonesia". Nature. 431 (7012): 1055–61. doi:10.1038/nature02999. PMID 15514638.

- Davidson, I. (2007). "As large as you need and as small as you can—implications of the brain size of Homo floresiensis". In Schalley, A.C.; Khlentzos, D. (eds.). Mental States: Evolution, function, nature; 2. Language and cognitive structure. Studies in language companion. 92–93. John Benjamins. pp. 35–42. ISBN 978-9027231055.

- Diamond J (1991). The Third Chimpanzee.

- Diamond J (1997). Why is Sex Fun?.

References

| Wikispecies has information related to Homininae. |

- Hollox, Edward; Hurles, Matthew; Kivisild, Toomas; Tyler-Smith, Chris (2013). Human Evolutionary Genetics (2nd ed.). Garland Science. ISBN 978-0-8153-4148-2.

- "Homininae". NCBI Taxonomy Browser. 207598.

External links

| The Wikibook Dichotomous Key has a page on the topic of: Homininae |

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).