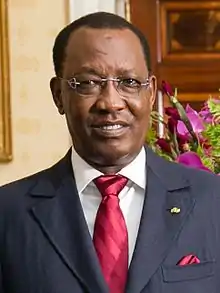

Idriss Déby

Marshal Idriss Déby Itno (Arabic: إدريس ديبي Idrīs Daybī Itnū; born 18 June 1952)[5] is a Chadian politician who has been the President of Chad since 1990. He is also head of the ruling Patriotic Salvation Movement. Déby is of the Bidyat clan of the Zaghawa ethnic group. He took power at the head of a rebellion against President Hissène Habré in December 1990 and has since survived various rebellions and coup attempts against his own rule. He won elections in 1996 and 2001, and after term limits were eliminated he won again in 2006, 2011, and 2016. He added "Itno" to his surname in January 2006. He is a graduate of Muammar Gaddafi's World Revolutionary Center.[6] Déby's multi-decade rule has been described as authoritarian by several international media sources.[7][8][9]

Idriss Déby إدريس ديبي | |

|---|---|

| |

| President of Chad | |

| Assumed office 2 December 1990 | |

| Prime Minister | Jean Alingué Bawoyeu Joseph Yodoyman Fidèle Moungar Delwa Kassiré Koumakoye Koibla Djimasta Nassour Guelendouksia Ouaido Nagoum Yamassoum Haroun Kabadi Moussa Faki Pascal Yoadimnadji Adoum Younousmi Delwa Kassiré Koumakoye Youssouf Saleh Abbas Emmanuel Nadingar Djimrangar Dadnadji Kalzeubet Pahimi Deubet Albert Pahimi Padacké |

| Vice President | Bada Abbas Maldoum (1990–1991)[1][2] |

| Preceded by | Hissène Habré |

| Chairperson of the African Union | |

| In office 30 January 2016 – 30 January 2017 | |

| Preceded by | Robert Mugabe |

| Succeeded by | Alpha Condé[3] |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 18 June 1952 Berdoba, French Equatorial Africa (now Chad) |

| Political party | Patriotic Salvation Movement |

| Spouse(s) | Hinda Deby Itno (2005–present) Amani Musa Hilal[4] |

| Children | Mahamat Brahim |

| Religion | Islam |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1976–1990 |

| Rank | Marshal |

Youth and military career

Déby was born in the village of Berdoba, approximately 190 kilometers from Fada in northern Chad.[10] His father was a poor herder, who belongs to the Bidayat clan of the Zaghawa community. After attending the Qur'anic School in Tiné, he continued his studies at the École Française in Fada and later at Franco-Arab school (Lycée Franco-Arabe) in Abéché.[10] He also attended the Lycée Jacques Moudeina in Bongor and also holds a bachelor's degree in Science.[11] After finishing school, he entered the Officers' School in N'Djamena.[10] From there he was sent to France for training, returning to Chad in 1976 with a professional pilot certificate. He remained loyal to the army and to President Félix Malloum even after the country's central authority crumbled in 1979.[10] He returned from France in February 1979 and found the country had become a battleground for many armed groups.[10] Déby tied his fortunes to those of Hissène Habré, one of the chief Chadian warlords. A year after Habré became President in 1982, Déby was made commander-in-chief of the army. He distinguished himself in 1984 by destroying pro-Libyan forces in Eastern Chad. In 1985, Habré sent him to Paris to follow a course at the École de Guerre; on his return in 1986,[10] he was made chief military advisor to the Presidency. In 1987, he confronted Libyan forces on the field, with the help of France[10] in the so-called "Toyota War", adopting tactics that inflicted heavy losses on enemy forces. During the war, he also led a raid on Maaten al-Sarra Air Base in Kufrah, which located in Libyan territory.[10] A rift emerged on 1 April 1989 between Habré and Déby over the increasing power of the Presidential Guard. According to Human Rights Watch,[12] Habré was found responsible for "widespread political killings, systematic torture, and thousands of arbitrary arrests", as well as ethnic purges when it was perceived that group leaders could pose a threat to his rule, including many of Déby's Zaghawa ethnic group who supported the government.[10] Increasingly paranoid, Habré accused Déby, Mahamat Itno, the minister of interior, and Hassan Djamous, commander in chief of the Chadian army of preparing a coup d'état. Déby first fled to Darfur, and then to Libya, which he was welcomed by Muammar Gaddafi in Tripoli,[10] while Itno and Djamous were arrested and killed.[13] Since all three were ethnic Zaghawa, Habré started a targeted campaign against the group which saw hundreds seized, tortured and imprisoned. Dozens died in detention or were summarily executed.[13] In 2016, Habré was convicted of war crimes by a specially-created international tribunal in Senegal.[14] Once in Libya, Déby gave the Libyans detailed information about CIA operations in Chad. Gaddafi offered Déby military aid to seize power in Chad in exchange with Libyan prisoners of war.[10]

Déby moved to Sudan and formed the Patriotic Salvation Movement, an insurgent group, supported by Libya and Sudan, which started operations against Habré in October 1989. He unleashed a decisive attack on 10 November 1990, and on 2 December Déby's troops marched unopposed into the capital, N'Djaména.

President of Chad

Idriss Déby assumed Chad's presidency in 1990, and has been re-elected with a majority of votes every five years.

1990s

After three months of provisional government, on 28 February 1991, a charter was approved for Chad with Déby as president. During the following two years, Déby faced a series of coup attempts as government forces clashed with pro-Habré rebel groups, such as the Movement for Democracy and Development (MDD).[15] Seeking to quell dissent, in 1993 Chad legalized political parties and held a National Conference which resulted in the gathering of 750 delegates, the government, trade unions and the army to discuss the establishment of a pluralist democracy.[16]

However, unrest continued. The Comité de Sursaut National pour la Paix et la Démocratie (CSNPD), led by Lt. Moise Kette and other southern groups sought to prevent the Déby government from exploiting oil in the Doba Basin[17] and started a rebellion that left hundreds dead. A peace agreement was reached in 1994, but it broke down shortly. Two new groups, the Armed Forces for a Federal Republic (FARF) led by former Kette ally Laokein Barde, and the Democratic Front for Renewal (FDR), and a reformulated MDD clashed with government forces from 1994 to 1995.

Déby, in the mid-1990s, gradually restored basic functions of government and entered into agreements with the World Bank and IMF to carry out substantial economic reforms.

A new constitution was approved by referendum in March 1996, followed by a presidential election in June. Déby placed on the first round but fell short of a majority; he was then elected president in the second round, held in July, with 69% of the vote.[18]

2000s

Idriss Déby was re-elected in the May 2001 presidential election, winning in the first round with 63.17% of the vote, according to official results.[18][19] A civil war between Christians and Muslims erupted in 2005, accompanied by tensions with Sudan. An attempted coup d'état, involving the shooting down of Déby's plane, was foiled in March 2006.[20]

In mid-April 2006, there was fighting with rebels at N'Djaména, although the fighting soon subsided with government forces still in control of the capital.[21] Déby subsequently broke ties with Sudan, accusing it of backing the rebels,[22] and said that the May 2006 election would still take place.[23]

Deby was sworn in for another term in office on 8 August 2006.[24] Sudanese president Omar al-Bashir attended Déby's inauguration, and the two leaders agreed to restore diplomatic relations on this occasion.[25]

After Déby's re-election, several rebel groups broke apart. Déby was in Abéché from 11 to 21 September 2006, flying in a helicopter to personally oversee attacks on Rally of Democratic Forces rebels.[26]

The rebellion in the east continued, and rebels reached N'Djamena on 2 February 2008, with fighting occurring inside the city.[27] After days of fighting, the government remained in control of N'Djamena. Speaking at a press conference on 6 February, Déby said that his forces had defeated the rebels, whom he described as "mercenaries directed by Sudan", and that his forces were in "total control" of the city as well as the whole country.[28]

Against this backdrop, in June 2005, a successful referendum was held to eliminate a two-term constitutional limit, which enabled Déby to run again in 2006.[29] More than 77% of voters approved.[30] Déby was a candidate in the 2006 presidential election, held 3 May, which was greeted with an opposition boycott. According to official results Déby won the election with 64.67% of the vote.[31]

In 2000, with the north/south dispute quelled, Déby's government started building the country's first oil pipeline, the 1,070 kilometer Chad-Cameroon project.[32] The pipeline was completed in 2003 and praised by the World Bank as "an unprecedented framework to transform oil wealth into direct benefits for the poor, the vulnerable and the environment".[33]

Oil exploitation in the southern Doba region began in June 2000, with World Bank Board approval to finance a small portion of a project, the Chad-Cameroon Petroleum Development Project, aimed at transport of Chadian crude through a 1000-km buried pipeline through Cameroon to the Gulf of Guinea. The project established unique mechanisms for World Bank, private sector, government, and civil society collaboration to guarantee that future oil revenues benefit populations and result in poverty alleviation.

However, with Chad having only a 12.5M stake in the oil field, not much wealth was transferred to the country. In 2006, Déby made international news after calling for his country to have a 60 percent stake in the Chad-Cameroon oil output after receiving "crumbs" from foreign companies running the industry.[34] He said Chevron and Petronas were refusing to pay taxes totalling $486.2 million. Chad passed a World Bank-backed oil revenues law that required most of its oil revenue to be allocated to health, education and infrastructure projects. The World Bank had previously frozen an oil revenue account in a dispute over how Chad spent its oil profits.[35] Déby rejected those claims, arguing that the country does not receive nearly enough royalties to make meaningful change in the fight against poverty.

2010s

On 25 April 2011, Déby was re-elected for a fourth term with 88.7% of the vote and reappointed Emmanuel Nadingar as Prime Minister.[36]

Because of Chad's strategic position in West Africa, Idriss Déby sent troops or played a key mediating role in tackling the multiple regional crises, such as Darfur, the Central African Republic (CAR), Mali, as well as the fight against Boko Haram.

With the security situation in the Central African Republic deteriorating, Déby decided in 2012 to deploy 400 troops to fight the CAR rebels. In January 2013, Chad also sent 2000 troops to fight Islamist groups in Mali,[37] as part of France's Operation Serval.

Chad’s recent history, under Déby's leadership, has been characterized by endemic corruption and a deeply entrenched patronage system that permeates society, according to Transparency International.[38] The recent exploitation of oil has fueled corruption, as revenues have been misused by government to strengthen its armed forces and reward its cronies, which contributes to the undermining of the country’s governance system.[38] In 2006, Chad was placed at the top of the list of the world's most corrupt nations by Forbes magazine,[39][40][41][42] In 2012, Déby launched a nationwide anticorruption campaign called "Operation Cobra," which reportedly recovered some $50 million in embezzled funds.[43][44] Nongovernmental organizations say, however, that Déby has used such initiatives to punish rivals and reward cronies.[45] As of 2016, Transparency International ranked Chad 147 out of 168 nations on its corruption index.[46]

Faced with a growing threat from Boko Haram, a terrorist group aligned to the Islamic State operating in northern Nigeria, Idriss Déby increases Chad's participation in the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF), a combined multinational formation comprising units from Niger, Nigeria, Benin and Cameroon.[47] In August 2015, Déby claims in an interview that the MNJTF has successfully "decapited" Boko Haram.[48]

In January 2016, Idriss Déby succeeded Zimbabwe's Robert Mugabe to become the chairman of the African Union for a one-year term. Upon his inauguration, Déby told presidents that conflicts around the continent had to end "Through diplomacy or by force... We must put an end to these tragedies of our time. We cannot make progress and talk of development if part or our body is sick. We should be the main actors in the search for solution to Africa's crises".[49] One of Déby's first priorities was to accelerate the fight against Boko Haram. On 4 March, the African Union agreed to expand the Multinational Joint Task Force (MNJTF) to 10 000 troops.

During the 21st Conference of the Parties (COP21) in Paris, Idriss Déby raised the issue of Lake Chad, whose area was a small fraction of what it had been in 1973, and called on the international community to provide financing to protect the ecosystem.[50]

In Fébruary 2016, Déby was nominated by the Patriotic Salvation Movement to run for a new term in the April 2016 Presidential elections.[51] He pledged to reinstate term limits in the constitution by saying that "We must limit terms, we must not concentrate on a system in which a change in power becomes difficult. "In 2005 the constitutional reform was conducted in a context where life of the nation was in danger".[52]

In 2017, the United States Justice Department alleged Déby accepted a $2 million bribe in return for providing a Chinese company with an opportunity to obtain oil rights in Chad without international competition.[53]

In January 2019, Déby and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu announced the resumption of diplomatic relations between Chad and Israel. Netanyahu described his visit to Chad as “part of the revolution we are having in the Arab and Muslim world.”[54]

2020s

Déby signed a bill abolishing capital punishment in Chad in 2020. The firing squad had last been used on terrorists in 2015.[55]

Family

Déby has been married several times and has at least a dozen children. He married Hinda (b. 1977) in September 2005. Reputed for her beauty, this marriage attracted much attention in Chad, and due to tribal affiliations it was seen by many as a strategic means for Déby to bolster his support while under pressure from rebels.[56] Hinda is a member of the Civil Cabinet of the Presidency, serving as Special Secretary.[57]

On 2 July 2007, Déby's son Brahim (age 27) was found dead in the parking garage of his apartment near Paris. According to the autopsy report, he had likely been asphyxiated by white powder from a fire extinguisher. A murder inquiry was launched by the French police. Brahim had been sacked as presidential advisor the year before, after being convicted of possessing drugs and weapons. Blogger Makaila Nguebla attributes the defection of many Chadian government leaders to their indignation over Brahim's conduct: "He is at the root of all the frustration. He used to slap government ministers, senior Chadian officials were humiliated by Déby's son."[58]

Déby is a Muslim.[59]

See also

- Heads of state of Chad

- Human rights in Chad

References

- Lansford, Tom (25 April 2017). Political Handbook of the World 2016-2017. CQ Press. ISBN 9781506327150. Retrieved 22 November 2017 – via Google Books.

- "Chiefs of State and Cabinet members of foreign governments / National Foreign Assessment Center. 1991Jan-June". hdl:2027/osu.32435024019754. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Guinea President Alpha Conde elected AU chair succeeding Deby". The Star Kenya. 30 January 2017.

- "Chad president weds Janjaweed chief daughter". Wayback Machine. 21 January 2012. Archived from the original on 25 January 2012.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- http://id.loc.gov/authorities/names/n94050752.html

- Douglas Farah (4 March 2011). "Harvard for Tyrants". The Foreign Policy.

- "Chad's authoritarian Deby unwilling to quit". Deutsche Welle. 8 April 2016. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- Haynes, Suyin (28 March 2019). "This African Country Has Had a Yearlong Ban on Social Media. Here's What's Behind the Blackout". Time. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- Werman, Marco (5 June 2012). "ExxonMobil and Chad's Authoritarian Regime: An 'Unholy Bargain'". The World. Public Radio International. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- Dictionary of African Biography. OUP USA. 2 February 2012. pp. 172–173. ISBN 9780195382075.

- "Biography of President IDRISS DEBY ITNO". Chad Embassy in Kuwait. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- "Q&A: The Case of Hissène Habré before the Extraordinary African Chambers in Senegal". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- "Chad: The Victims of Hissène Habré Still Awaiting Justice: Historical Background". www.hrw.org. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- "Hissene Habre: Chad's ex-ruler convicted of crimes against humanity". BBC News. Retrieved 29 January 2017.

- "Terrorist Organization Profile - START - National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism". www.start.umd.edu. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- "Chronology for Southerners in Chad". University of Maryland. 16 July 2010.

- "Chad" (PDF). stanford.edu. Stanford. 7 July 2006.

- Elections in Chad, African Elections Database.

- "Chad: Council releases final polls results; Deby "elected" with 63.17 per cent", Radiodiffusion Nationale Tchadienne (nl.newsbank.com), 13 June 2001.

- "Coup attempt foiled, government says", The New Humanitarian (formerly IRIN News), 15 March 2006.

- "Chad confronts rebels in capital", BBC News, 13 April 2006.

- Andrew England, "Chad severs ties with Sudan", Financial Times, 15 April 2006.

- Rebels 'will not delay' Chad poll", BBC News, 18 April 2006.

- "Deby sworn in as Chad's president", People's Daily Online, 9 August 2006.

- "Chad and Sudan resume relations", BBC News, 9 August 2006.

- "Chad: New Fronts Open in Eastern Fighting" allAfrica.com, 21 September 2006.

- "Battle rages for Chadian capital", Al Jazeera, 2 February 2008.

- "Chad’s leader says government ‘in total control’", Associated Press (MSNBC), 6 February 2008.

- "Strong yes vote in referendum allows President Deby to seek a new term", IRIN, 22 June 2005.

- "Chad votes to end two-term limit". BBC. 22 June 2005. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- "Déby win confirmed, but revised down to 64.67 pct", IRIN, 29 May 2006.

- "Chad-Cameroon Pipeline Case Study". www.columbia.edu. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- Toïngar, Ésaïe (16 January 2014). Idriss Deby and the Darfur Conflict. McFarland. ISBN 9780786492572.

- "UPDATE 3-Chad leader wants majority stake in oil output". Reuters UK. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- "Petronas disputes Chad's tax claims" Archived 3 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Aljazeera.net, 30 August 2006.

- "Bashir attends Deby inauguration". News24. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- "Mali crisis: Chad's Idriss Deby announces troop pullout - BBC News". BBC News. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- e.V., Transparency International. "Research - Corruption Q&As - Overview of corruption and anti-corruption in Chad". www.transparency.org. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

- David A. Andelman (3 April 2007). "In Pictures: Most Corrupt Nations". Forbes. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- "Environmental Justice Case Study: The Chad/Cameroon Oil and Pipeline Project". Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- "Steve Coll On ExxonMobil's Sinister Kingdom and 'Private Empire'". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- "Mr. Lonely". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- "Chad". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- Yacoub, Djamil Ahmat. "Enfin, une "opération Cobra" lancée contre l'enrichissement illicite au Tchad". Alwihda Info - Actualités TCHAD, Afrique, International. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- "Transparency International Country Profile: Chad" (PDF).

- e.V., Transparency International. "Transparency International - Country Profiles". www.transparency.org. Retrieved 24 April 2016.

- "Boko Haram est "décapité", assure le président tchadien Idriss Déby - RFI". RFI Afrique (in French). Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- "Boko Haram has been 'decapitated': Chadian leader". Yahoo News. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- "Chad's Deby becomes new African Union chairman". Yahoo News. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- "Lac Tchad et COP 21 : le cri d'alarme d'Idriss Déby". Green et Vert. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- "Chad President Idriss Deby seeks fifth term in office". BBC News. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- "Chad President Idriss Deby seeks fifth term in office - BBC News". BBC News. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- "U.S. charges two with bribing African officials for China energy firm". 21 November 2017. Retrieved 22 November 2017 – via Reuters.

- Israeli PM visits Chad to restore relations. 20 January 2019. AA.

- https://www.iol.co.za/news/africa/chad-abolishes-the-death-penalty-47314174

- Emily Wax, "New First Lady Captivates Chad", The Washington Post, 2 May 2006, page A17.

- "Liste des Membres du Cabinet Civil de la Présidence de la République", Chadian presidency website (accessed 4 May 2008) (in French).

- "Chad leader's son killed in Paris" BBC News, 2 July 2007.

- "His Excellency President Idriss Deby Itno". The Muslim 500. Retrieved 2 August 2019.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Hissène Habré |

President of Chad 1990–present |

Incumbent |

| Diplomatic posts | ||

| Preceded by Robert Mugabe |

Chairperson of the African Union 2016–2017 |

Succeeded by Alpha Condé |