Siad Barre

Jaalle Mohamed Siad Barre (Somali: Maxamed Siyaad Barre; Arabic: محمد سياد بري; 1910 – January 2, 1995)[3] was a Somali General who served as the President of the Somali Democratic Republic from 1969 to 1991. Barre, a major general of the gendarmerie, became President of Somalia after the 1969 coup d'état that overthrew the Somali Republic following the assassination of President Abdirashid Ali Shermarke. The Supreme Revolutionary Council military junta under Barre reconstituted Somalia as a one-party Marxist–Leninist communist state, renaming the country the Somali Democratic Republic and adopting scientific socialism, with support from the Soviet Union. Barre's early rule was characterised by attempts at widespread modernization, nationalization of banks and industry, promotion of cooperative farms, a new writing system for the Somali language, and anti-tribalism. The Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party became Somalia's vanguard party in 1976, and Barre started the Ogaden War against Ethiopia on a platform of Somali nationalism and pan-Somalism. Barre's popularity was highest during the seven months between September 1977 and March 1978 when Barre captured virtually the entirety of the Somali region.[4] It declined from the late-1970s following Somalia's defeat in the Ogaden War, triggering the Somali Rebellion and severing ties with the Soviet Union. Opposition grew in the 1980s due to his increasingly dictatorial rule, growth of tribal politics, abuses of the National Security Service including the Isaaq genocide, and the sharp decline of Somalia's economy. In 1991, Barre's government collapsed as the Somali Rebellion successfully ejected him from power, leading to the Somali Civil War, and forcing him into exile where he died in Nigeria in 1995.[5][6][7]

Siad Barre | |

|---|---|

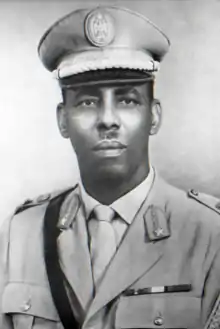

Military portrait of Major General Mohamed Siad Barre, 1970 | |

| 3rd President of Somalia | |

| In office October 21, 1969 – January 26, 1991 | |

| Vice President | Muhammad Ali Samatar |

| Preceded by | Mukhtar Mohamed Hussein |

| Succeeded by | Ali Mahdi Muhammad |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Mohamed Siad Barre 1910 Shilavo, Ogaden[1] |

| Died | January 2, 1995 (aged 84–85) Lagos, Nigeria |

| Resting place | Garbaharey, Somalia |

| Political party | Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party |

| Spouse(s) | Khadija Maalin Dalyad Haji Hashi[1] |

| Relations | Abdirahman Jama Barre[2] |

| Children | 29, including Maslah Mohammed Siad Barre |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | Somali National Army |

| Years of service | 1935–1941 1960–1991 |

| Rank | |

| Battles/wars | Second Italo-Ethiopian War East African Campaign (World War II) 1964 Ethiopian-Somali Border War Shifta War Ogaden War 1982 Ethiopian-Somali Border War Somali Rebellion Somali Civil War |

Early years

Mohamed Siad Barre was born in Shilavo, Ogaden which is now present-day Ethiopia in the year 1910.[8][9][10] Barre's parents died when he was ten years old, and after receiving his primary education in the town of Luuq in southern Italian Somalia he moved to the capital Mogadishu to pursue his secondary education.[10] Barre seems to have probably participated as a Zaptié in the southern theatre of the Italian conquest of Ethiopia in 1936, and later joined the colonial police force during the British Somaliland military administration, rising to major general, the highest possible rank.[11][10] In 1946, Barre supported the Somali Conference (Italian: Conferenza Somala), a political group of parties and clan associations that were hostile to the Somali Youth League and were supported by the local Italian farmers. The group presented a petition to the "Four Powers" Investigation Commission in order to allow that the administration of the United Nations Trust Territory could be entrusted for thirty years to Italy.[12] In 1950, shortly after Italian Somaliland became a United Nations Trust Territory under Italian administration for ten years, Barre (who was fluent in Italian) attended the Carabinieri police school in Florence for two years.[13][10] Upon his return to Somalia, Barre remained with the military and eventually became Vice Commander of the Somali Army when the country gained its independence in 1960 as the Somali Republic.

In the early 1960s, after spending time with Soviet officers in joint training exercises, Barre became an advocate of Soviet-style Marxist-Leninist government, believing in a socialist government and a stronger sense of Somali nationalism.

Seizure of power

In 1969, following the assassination of Somalia's second president, Abdirashid Ali Shermarke, the military staged the 1969 coup d'état on October 21, the day after Shermarke's funeral, overthrowing the Somali Republic's government. The Supreme Revolutionary Council (SRC), a military junta led by Major General Barre, Lieutenant Colonel Salaad Gabeyre Kediye and Chief of Police Jama Ali Korshel, assumed power and filled the top offices of the government, with Kediye officially holding the title of "Father of the Revolution," although Barre shortly afterwards became the head of the SRC.[14] The SRC subsequently renamed the country the Somali Democratic Republic, arrested members of the former government, banned political parties, dissolved the parliament and the Supreme Court, and suspended the constitution.[15][16][17][18]

Presidency

Barre assumed the position of President of Somalia, styled the "Victorious Leader" (Guulwade), and fostered the growth of a personality cult with portraits of him in the company of Marx and Lenin lining the streets on public occasions.[19] Barre advocated a form of scientific socialism based on the Qur'an and Marxism, with heavy influences of Somali nationalism.

Supreme Revolutionary Council

The Supreme Revolutionary Council established large-scale public works programs and successfully implemented an urban and rural literacy campaign, which helped dramatically increase the literacy rate. Barre began a program of nationalising industry and land, and the new regime's foreign policy placed an emphasis on Somalia's traditional and religious links with the Arab world, eventually joining the Arab League in 1974.[10] That same year, Barre also served as chairman of the Organization of African Unity (OAU), the predecessor of the African Union (AU).[20]

In July 1976, Barre's SRC disbanded itself and established in its place the Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party (SRSP), a one-party government based on scientific socialism and Islamic tenets. The SRSP was an attempt to reconcile the official state ideology with the official state religion by adapting Marxist precepts to local circumstances. Emphasis was placed on the Muslim principles of social progress, equality and justice, which the government argued formed the core of scientific socialism and its own accent on self-sufficiency, public participation and popular control, as well as direct ownership of the means of production. While the SRSP encouraged private investment on a limited scale, the administration's overall direction was essentially communist.[16]

A new constitution was promulgated in 1979 under which elections for a People's Assembly were held. However, the Politburo of Barre's Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party continued to rule.[18] In October 1980, the SRSP was disbanded, and the Supreme Revolutionary Council was re-established in its place.[16]

Language and anti-clanism

One of the first and principal objectives of the revolutionary regime was the adoption of a standard national writing system. Barre supported the official use of Latin script for the Somali language, replacing Arabic script and Wadaad writing that had been used for centuries. Shortly after coming to power, Barre introduced the Somali language (Af Soomaali) as the official language of education, and selected the modified Somali Latin alphabet developed by the Somali linguist Shire Jama Ahmed as the nation's standard orthography. From then on, all education in government schools had to be conducted in Somali, and in 1972, all government employees were ordered to learn to read and write Somali within six months. The reason given for this was to decrease a growing rift between those who spoke the colonial languages, Italian or English, and those who did not, as many of the high ranking positions in the former government were given to people who spoke either Italian or English.

Additionally, Barre also sought to eradicate the importance of the Somali clan system (qabil) within Somalia's government and civil society. The inevitable first question that Somalis asked one another when they met was, '"What is your clan?", but when this was considered to be against to the purpose of a modern state, Somalis began to pointedly ask, "What is your ex-clan?". Barre outlawed this question and a broad range of other activities classified as "clanism", with informers reporting qabilists, those considered to propagate the clan system, to the government, leading to arrests and imprisonment.

On a more symbolic level, Barre had repeated a number of times, "Whom do you know? is changed to: What do you know?", and this incantation became part of a popular street song in Somalia.[21] He also promoted a number of favored greetings, such as the singular jaalle (comrade) or the plural jaalleyaal (comrades).[22]

Nationalism and Greater Somalia

Barre advocated the concept of a Greater Somalia (Soomaaliweyn), which refers to those regions in the Horn of Africa in which ethnic Somalis reside and have historically represented the predominant population. Greater Somalia encompasses Somalia, Djibouti, the Ogaden in Ethiopia, and Kenya's former North Eastern Province, regions of the Horn of Africa where Somalis form the majority of the population to some proportion.[23][24][25] In July 1977, the Ogaden War broke out after the Barre's government sought to incorporate the various Somali-inhabited territories of the region into a Greater Somalia, beginning with the Ogaden. The Somali national army invaded Ethiopia, which was now under communist rule of the Soviet-backed Derg, and was successful at first, capturing most of the territory of the Ogaden. The invasion reached an abrupt end with the Soviet Union's shift of support to Ethiopia, followed by almost the entire communist world siding against Somalia. The Soviets halted their previous supplies to Barre's regime and increased the distribution of aid, weapons, and training to the Ethiopian government, and also brought in around 15,000 Cuban troops to assist the Ethiopian regime. In 1978, the Somali troops were ultimately pushed out of the Ogaden.

Foreign relations

Control of Somalia was of great interest to both the Soviet Union and the United States due to the country's strategic location at the mouth of the Red Sea. After the Soviets broke with Somalia in the late 1970s, Barre subsequently expelled all Soviet advisers, tore up his friendship treaty with the Soviet Union, and switched allegiance to the West, announcing this in a televised speech in English.[26] Somalia also broke all ties with the Soviet Bloc and the Second World (except China and Romania).[27] The United States stepped in and until 1989, was a strong supporter of the Barre government for whom it provided approximately US$100 million per year in economic and military aid,[28] meeting in 1982 with Ronald Reagan to announce the new relationship between the US and Somalia.[29]

In September 1972 Tanzanian-sponsored rebels attacked Uganda. Ugandan President Idi Amin requested Barre's assistance, and he subsequently mediated a non-aggression pact between Tanzania and Uganda. For his actions, a road in Kampala was named after Barre.[30]

On October 17 and 18, 1977, a Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) group hijacked Lufthansa Flight 181 to Mogadishu, holding 86 hostages. West German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt and Barre negotiated a deal to allow a GSG 9 anti-terrorist unit into Mogadishu to free the hostages.[31]

In January 1986, Barre and the Ethiopian dictator Mengistu Haile Mariam met in Djibouti to normalise relations between their respective countries.[5][32] The Ethiopian-Somali agreement was signed by 1988 and Barre disbanded his clandestine anti-Ethiopian organisation the Western Somali Liberation Front.[5][32] In return, Barre hoped that Mengistu would disarm Somali National Movement rebels active on the Ethiopian side of the border, however did this not materialise since the SNM relocated to Northern Somalia in response to this agreement.[5][32]

Domestic programs

During the first five years, Barre's government set up several cooperative farms and factories of mass production such as mills, sugar cane processing facilities in Jowhar and Afgooye, and a meat processing house in Kismayo.

Another public project initiated by the government was the Shalanbood Sanddune Stoppage: from 1971 onwards, a massive tree-planting campaign on a nationwide scale was introduced by Barre's administration to halt the advance of thousands of acres of wind-driven sand dunes that threatened to engulf towns, roads, and farm land.[33] By 1988, 265 hectares of a projected 336 hectares had been treated, with 39 range reserve sites and 36 forestry plantation sites established.[34]

Between 1974 and 1975, a major drought referred to as the Abaartii Dabadheer ("The Lingering Drought") occurred in the northern regions of Somalia. The Soviet Union, which at the time maintained strategic relations with the Barre government, airlifted some 90,000 people from the devastated regions of Hobyo and Caynaba. New settlements of small villages were created in the Jubbada Hoose (Lower Jubba) and Jubbada Dhexe (Middle Jubba) regions, with these new settlements known as the Danwadaagaha or "Collective Settlements". The transplanted families were introduced to farming and fishing, a change from their traditional pastoralist lifestyle of livestock herding. Other such resettlement programs were also introduced as part of Barre's effort to undercut clan solidarity by dispersing nomads and moving them away from clan-controlled land.

Economic policies

As part of Barre's socialist policies, major industries and farms were nationalised, including banks, insurance companies and oil distribution farms. By the mid-to-late-1970s, public discontent with the Barre regime was increasing, largely due to corruption among government officials as well as poor economic performance. The Ogaden War had also weakened the Somali army substantially and military spending had crippled the economy. Foreign debt increased faster than export earnings, and by the end of the decade, Somalia's debt of 4 billion shillings equaled the earnings from seventy-five years' worth of banana exports.[35]

By 1978, manufactured goods exports were almost non-existent, and with the lost support of the Soviet Union the Barre government signed a structural adjustment agreement with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) during the early 1980s. This included the abolishment of some government monopolies and increased public investment. This and a second agreement were both cancelled by the mid-1980s, as the Somali army refused to accept a proposed 60 percent cut in military spending. New agreements were made with the Paris Club, the International Development Association and the IMF during the second half of the 1980s. This ultimately failed to improve the economy which deteriorated rapidly in 1989 and 1990, and resulted in nationwide commodity shortages.

Car collision

In May 1986, President Barre suffered serious injuries in a life-threatening automobile collision near Mogadishu, when the car that was transporting him smashed into the back of a bus during a heavy rainstorm.[36] He was treated in a hospital in Saudi Arabia for head injuries, broken ribs and shock over a period of a month.[37][38] Lieutenant General Mohammad Ali Samatar, then Vice President, subsequently served as de facto head of state for the next several months. Although Barre managed to recover enough to present himself as the sole presidential candidate for re-election over a term of seven years on December 23, 1986, his poor health and advanced age led to speculation about who would succeed him in power. Possible contenders included his son-in-law General Ahmed Suleiman Abdille, who was at the time the Minister of the Interior, in addition to Barre's Vice President Lt. Gen. Samatar.[36][37]

Human rights abuses

Part of Barre's time in power was characterized by oppressive dictatorial rule, including persecution, jailing and torture of political opponents and dissidents. The United Nations Development Programme stated that "the 21-year regime of Siyad Barre had one of the worst human rights records in Africa."[39] In January 1990, the Africa Watch Committee, a branch of Human Rights Watch organizational released an extensive report titled "Somalia A Government At War with Its Own People" composing of 268 pages, the report highlights the widespread violations of basic human rights in the northern regions of Somalia. The report includes testimonies about the killing and conflict in northern Somalia by newly arrived refugees in various countries around the world. Systematic human rights abuses against the dominant Isaaq clan in the north was described in the report as "state sponsored terrorism" "both the urban population and nomads living in the countryside [were] subjected to summary killings, arbitrary arrest, detention in squalid conditions, torture, rape, crippling constraints on freedom of movement and expression and a pattern of psychological intimidation. The report estimates that 50,000 to 60,000 people were killed from 1988 to 1989."[40] Amnesty International went on to report that torture methods committed by Barre's National Security Service (NSS) included executions and "beatings while tied in a contorted position, electric shocks, rape of woman prisoners, simulated executions and death threats."[41]

In September 1970, the government introduced the National Security Law No. 54, which granted the NSS the power to arrest and detain indefinitely those who expressed critical views of the government, without ever being brought to trial. It further gave the NSS the power to arrest without a warrant anyone suspected of a crime involving "national security". Article 1 of the law prohibited "acts against the independence, unity or security of the State", and capital punishment was mandatory for anyone convicted of such acts.[42]

From the late 1970s, and onwards Barre faced a shrinking popularity and increased domestic resistance. In response, Barre's elite unit, the Red Berets (Duub Cas), and the paramilitary unit called the Victory Pioneers carried out systematic terror against the Majeerteen, Hawiye, and Isaaq clans.[43] The Red Berets systematically smashed water reservoirs to deny water to the Majeerteen and Isaaq clans and their herds. More than 2,000 members of the Majeerteen clan died of thirst, and an estimated 5,000 Isaaq were killed by the government. Members of the Victory Pioneers also raped large numbers of Majeerteen and Isaaq women, and more than 300,000 Isaaq members fled to Ethiopia.[44][45]

Clannism

After the Ogaden War, Barre adopted a "clannism" ideology and abandoned his "socialist facade" to hold onto power.[32] A 120,000 strong army was built for internal repression of the public and to encourage rural clan based conflicts in addition to urban clan directed massacres by specialised armed forces.[32] Barre also singled out the Isaaq clan for a "neo-fascist" type punishment resulting in a "semi-colonial" type subjugation which fuelled collective self assertion to supporters of the Somali National Movement.[32]

By the mid-1980s, more resistance movements supported by Ethiopia's communist Derg administration had sprung up across the country. Barre responded by ordering punitive measures against those he perceived as locally supporting the guerillas, especially in the northern regions. The clampdown included bombing of cities, with the northwestern administrative center of Hargeisa, a Somali National Movement (SNM) stronghold, among the targeted areas in 1988.[46][47] The bombardment was led by General Mohammed Said Hersi Morgan, Barre's son-in-law, and resulted in the deaths of 50,000 people in the north.[48]

Rebellion and ouster

After fallout from the unsuccessful Ogaden campaign, Barre's administration began arresting government and military officials under suspicion of participation in the 1978 coup d'état attempt.[49][50] Most of the people who had allegedly helped plot the putsch were summarily executed.[51] However, several officials managed to escape abroad and started to form the first of various dissident groups dedicated to ousting Barre's regime by force.[52]

A new constitution was promulgated in 1979 under which elections for a People's Assembly were held. However, Barre and the Politburo of his Somali Revolutionary Socialist Party continued to rule.[18] In October 1980, the SRSP was disbanded, and the Supreme Revolutionary Council was re-established in its place.[16] By that time, the moral authority of Barre's ruling Supreme Revolutionary Council had begun to weaken. Many Somalis were becoming disillusioned with life under military dictatorship. The regime was further weakened in the 1980s as the Cold War drew to a close and Somalia's strategic importance was diminished. The government became increasingly totalitarian, and resistance movements, supported by Ethiopia's communist Derg administration, sprang up across the country. This eventually led in 1991 to the outbreak of the civil war, the toppling of Barre's regime and the disbandment of the Somali National Army (SNA). Among the militia groups that led the rebellion were the Somali Salvation Democratic Front (SSDF), United Somali Congress (USC), Somali National Movement (SNM) and the Somali Patriotic Movement (SPM), together with the non-violent political oppositions of the Somali Democratic Movement (SDM), the Somali Democratic Alliance (SDA) and the Somali Manifesto Group (SMG). Siad Barre escaped from his palace towards the Kenyan border in a tank.[53] Many of the opposition groups subsequently began competing for influence in the power vacuum that followed the ouster of Barre's regime. In the south, armed factions led by USC commanders General Mohamed Farah Aidid and Ali Mahdi Mohamed, in particular, clashed as each sought to exert authority over the capital.[54]

Exile and death

After fleeing Mogadishu on January 26, 1991 with his son-in-law General Morgan, Barre temporarily remained in Burdhubo, in southwestern Somalia, his family's stronghold.[55] The former dictator fled in a tank filled with reserves from the Somalian central bank.[56][57] [58][59] This included gold and foreign currency estimated to have been worth $27 million.[56]

From there, he launched a military campaign to return to power. He twice attempted to retake Mogadishu, but in May 1991 was overwhelmed by General Mohamed Farrah Aidid's army and forced into exile. Barre initially moved to Nairobi, Kenya, but opposition groups there protested his arrival and the Kenyan government's support for him.[60] In response to the pressure and hostilities, he moved two weeks later to Nigeria. Barre died of a heart attack on January 2, 1995, in Lagos.[60] He was buried in Garbaharey, Somalia.

Honours

Order of the National Flag, First Class, of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea – 1972[61]

Order of the National Flag, First Class, of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea – 1972[61]

See also

References

- Greenfield, Richard (January 3, 1995). "Obituary: Mohamed Said Barre". The Independent. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- Kapteijns, Lidwien (December 18, 2012). Clan Cleansing in Somalia: The Ruinous Legacy of 1991. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0812207583.

- James, George (January 3, 1995). "Somalia's Overthrown Dictator, Mohammed Siad Barre, Is Dead". The New York Times. Retrieved July 1, 2017.

- Yihun, Belete Belachew. "Ethiopian foreign policy and the Ogaden War: the shift from “containment” to “destabilization,” 1977–1991." Journal of Eastern African Studies 8.4 (2014): 677-691.

- Library of Congress. Federal Research Division (1993). "Siad Barre and Scientific Socialism". In Metz, Helen Chapin (ed.). Somalia: A Country Study. U.S. Government Publishing Office. ISBN 9780844407753.

- Library of Congress. Federal Research Division (1993). "Siad Barre's Repressive Measures". In Metz, Helen Chapin (ed.). Somalia: A Country Study. U.S. Government Publishing Office. ISBN 9780844407753.

- Library of Congress. Federal Research Division (1993). "The Social Order". In Metz, Helen Chapin (ed.). Somalia: A Country Study. U.S. Government Publishing Office. ISBN 9780844407753.

- Shillington, Kevin (July 4, 2013). Encyclopedia of African History 3-Volume Set. ISBN 9781135456702.

- Laitin, David D.; Samatar, Said S. (1987). Somalia: nation in search of a state. Boulder: Westview Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780566054594.

- Frankel, Benjamin (1992). The Cold War, 1945-1991: Leaders and other important figures in the Soviet Union, Eastern Europe, China, and the Third World. Gale Research. pp. 306. ISBN 9780810389281.

- Daniel Compagnon. "Le regime Syyad Barre"; p. 179

- Daniel Compagnon. "RESSOURCES POLITIQUES, REGULATION AUTORITAIRE ET DOMINATION PERSONNELLE EN SOMALIE LE REGIME SIYYAD BARRE (1969-1991)", Volume 1; p.163

- Mohamed Amin (March 5, 2014). "President Mohamed Siad Barre and Somali Officials speaking italian Part 1" – via YouTube.

- Adam, Hussein Mohamed; Ford, Richard (1997). Mending rips in the sky: options for Somali communities in the 21st century. Red Sea Press. p. 226. ISBN 9781569020739.

- Library of Congress. Federal Research Division (1993). "Coup d'Etat". In Metz, Helen Chapin (ed.). Somalia: A Country Study. U.S. Government Publishing Office. ISBN 9780844407753.

- Peter John de la Fosse Wiles, The New Communist Third World: an essay in political economy, (Taylor & Francis: 1982), p.279.

- Fage, J. D.; Crowder, Michael; Oliver, Roland Anthony (1984). The Cambridge History of Africa. 8. Cambridge University Press. p. 478. ISBN 9780521224093.

- The Encyclopedia Americana: complete in thirty volumes. Skin to Sumac. 25. Grolier. 1995. p. 214. ISBN 9780717201266.

- Metz, Helen C. (ed.) (1992), "Siad Barre and Scientific Socialism", Somalia: A Country Study, Washington, D.C.: Library of CongressCS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link).

- Oihe Yang, Africa South of the Sahara 2001, 30th Ed., (Taylor and Francis: 2000), p.1025.

- Laitin, David D., Politics, Language, and Thought, p. 89

- Jaamac, Faarax Maxamed. Aqoondarro waa u Nacab Jacayl. Jamhuuriyadda Dimoqraadiga Soomaaliya, Wasaaradda Hiddaha iyo Tacliinta Sare, 1974.

- The 1994 national census was delayed in the Somali Region until 1997. FDRE States: Basic Information - Somalia Archived May 22, 2005, at the Wayback Machine, Population (accessed March 12, 2006)

- Francis Vallat, First report on succession of states in respect of treaties: International Law Commission twenty-sixth session May 6 – July 26, 1974, (United Nations: 1974), p.20

- Africa Watch Committee, Kenya: Taking Liberties, (Yale University Press: 1991), p.269

- Gorman, Robert F. (1981). Political Conflict on the Horn of Africa. Westport, CT: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-030-59471-7. p.208

- Ingiriis, Mohamed (April 1, 2016). The Suicidal State in Somalia: The Rise and Fall of the Siad Barre Regime, 1969–1991. United States: University Press of America. pp. 147–150. ISBN 978-0-7618-6719-7.

- Mugabe, Faustin (November 20, 2017). "Somalia's Siad Barre saves Amin from Tanzanians". Daily Monitor. Retrieved March 28, 2019.

- "Der Preis für die Befreiung der Mogadischu-Geiseln" (in German). Welt. July 30, 2009. Retrieved January 5, 2020.

- Adam, Hussein M. (1994). "Formation and Recognition of New States: Somaliland in Contrast to Eritrea". Review of African Political Economy. 21 (59): 21–38. doi:10.1080/03056249408704034. ISSN 0305-6244. JSTOR 4006181.

- National Geographic Society (U.S.), National Geographic, Volume 159, (National Geographic Society: 1981), p.765.

- Hadden, Robert Lee. 2007. "The Geology of Somalia: A Selected Bibliography of Somalian Geology, Geography and Earth Science." Engineer Research and Development Laboratories, Topographic Engineering Center

- Metz, Helen C. (ed.) (1992), "The Socialist Revolution After 1975", Somalia: A Country Study, Washington, D.C.: Library of CongressCS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link).

- World of Information (Firm), Africa review, (World of Information: 1987), p.213.

- Arthur S. Banks, Thomas C. Muller, William Overstreet, Political Handbook of the World 2008, (CQ Press: 2008), p.1198.

- National Academy of Sciences (U.S.). Committee on Human Rights, Institute of Medicine (U.S.). Committee on Health and Human Rights, Scientists and human rights in Somalia: report of a delegation, (National Academies: 1988), p.9.

- UNDP, Human Development Report 2001-Somalia, (New York: 2001), p. 42

- Africa Watch Committee, Somalia: A Government at War with its Own People, (New York: 1990), p. 9

- Amnesty International, Torture in the Eighties, (Bristol, England: Pitman Press, 1984), p. 127.

- National Academy of Sciences (U.S.) Committee on Human Rights & Institute of Medicine (U.S.) Committee on Health and Human Rights, Scientists and human rights in Somalia: report of a delegation, (Washington D.C.: National Academy Press, 1988), p. 16.

- Metz, Helen C. (ed.) (1992), "Siad Barre's Repressive Measures", Somalia: A Country Study, Washington, D.C.: Library of CongressCS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link).

- Metz, Helen C. (ed.) (1992), "Persecution of the Majeerteen", Somalia: A Country Study, Washington, D.C.: Library of CongressCS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link).

- Metz, Helen C. (ed.) (1992), "Oppression of the Isaaq", Somalia: A Country Study, Washington, D.C.: Library of CongressCS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link).

- "Somalia — Government". Library of Congress. Retrieved February 15, 2014.

- Compagnon, Daniel (October 22, 2013). "State-sponsored violence and conflict under Mahamed Siyad Barre: the emergence of path dependent patterns of violence". World Peace Foundation, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- "Analysis: Somalia's powerbrokers". BBC News. January 8, 2002. Retrieved October 7, 2014.

- ARR: Arab report and record, (Economic Features, ltd.: 1978), p.602.

- Ahmed III, Abdul. "Brothers in Arms Part I" (PDF). WardheerNews. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 3, 2012. Retrieved February 28, 2012.

- New People Media Centre, New people, Issues 94–105, (New People Media Centre: Comboni Missionaries, 2005).

- Nina J. Fitzgerald, Somalia: issues, history, and bibliography, (Nova Publishers: 2002), p.25.

- Perlez, Jane; Times, Special to The New York (October 28, 1991). "Insurgents Claiming Victory in Somalia". Retrieved October 28, 2017 – via www.nytimes.com.

- Library Information and Research Service, The Middle East: Abstracts and index, Volume 2, (Library Information and Research Service: 1999), p.327.

- Bradbury, Mark. (1994). The Somali conflict : prospects for peace. Oxford [England]: Oxfam. ISBN 0-85598-271-3. OCLC 33119727.

- Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | Somalia: Civil War, Intervention and Withdrawal 1990 - 1995". Refworld. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- Perlez, Jane; Times, Special To the New York (January 28, 1991). "Insurgents Claiming Victory in Somalia (Published 1991)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 21, 2020.

- Perlez, Jane; Times, Special To the New York (January 28, 1991). "Insurgents Claiming Victory in Somalia (Published 1991)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- Alasow, Omar Abdulle (May 17, 2010). Violations of the Rules Applicable in Non-International Armed Conflicts and Their Possible Causes: The Case of Somalia. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-18988-1.

- "Former Somalian President Mohamed Siad Barre Dies". The Washington Post.

- Korea Today. Foreign Languages Publishing House (191): 10. 1972. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

Further reading

- Glickman, Harvey (ed.) (1992), Political Leaders of Contemporary Africa South of the Sahara, Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, ISBN 0313267812CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Shire, Mohammed Ibrahim, Somali President Mohammed Siad Barre: His Life and Legacy, (Cirfe Publications, 2011).

External links

- Mohamed Siad Barre biographical website (in Somali)

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Sheikh Mukhtar Mohamed Hussein |

President of Somalia 1969–1991 |

Succeeded by Ali Mahdi Muhammad |