Isabella I of Castile

Isabella I (Spanish: Isabel I, 22 April 1451 – 26 November 1504) was Queen of Castile from 1474 and, as the wife of King Ferdinand II, Queen of Aragon from 1479 until her death, reigning over a dynastically unified Spain jointly with her husband Ferdinand; together they would be known as the Catholic Monarchs. Isabella is considered the first Queen of Spain de facto, being described as such during her own lifetime, although Castile and Aragon de jure remained two different kingdoms until the Nueva Planta decrees of 1707 to 1716.

| Isabella I | |

|---|---|

Anonymous portrait of Isabella (c. 1490) | |

| Queen of Castile and León | |

| Reign | 11 December 1474 – 26 November 1504 |

| Coronation | 13 December 1474[1] |

| Predecessor | Henry IV |

| Successor | Joanna |

| Co-monarch | Ferdinand V |

| Queen consort of Aragon (more..) | |

| Tenure | 20 January 1479 – 26 November 1504 |

| Born | 22 April 1451 Madrigal de las Altas Torres |

| Died | 26 November 1504 (aged 53) Medina del Campo |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | |

| Issue among others... | |

| House | Trastámara |

| Father | John II of Castile |

| Mother | Isabella of Portugal |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

| Signature | |

After a struggle to claim her right to the throne, she reorganized the governmental system, brought the crime rate to the lowest it had been in years, and unburdened the kingdom of the enormous debt her brother had left behind. Isabella's marriage to Ferdinand in 1469 created the basis of the de facto unification of Spain. Her reforms and those she made with her husband had an influence that extended well beyond the borders of their united kingdoms. Isabella and Ferdinand are known for completing the Reconquista, ordering conversion of the Jews and Muslims from Spain, and for supporting and financing Christopher Columbus's 1492 voyage that led to the discovery of the New World by Europeans and to the establishment of Spain as a major power in Europe and much of the world for more than a century.[2] Isabella was granted, together with her husband, the title "the Catholic" by Pope Alexander VI, and was recognized in 1974 as a Servant of God by the Catholic Church.

Life

Early years

Isabella was born in Madrigal de las Altas Torres, Ávila, to John II of Castile and his second wife, Isabella of Portugal, on 22 April 1451.[3] At the time of her birth, she was second in line to the throne after her older half-brother Henry IV of Castile.[2] Henry was 26 at that time and married, but childless. Her younger brother Alfonso of Castile was born two years later on 17 November 1453, lowering her position to third in line.[4] When her father died in 1454, her half-brother ascended to the throne as King Henry IV of Castile. Isabella and her brother Alfonso were left in King Henry's care.[5] She, her mother, and Alfonso then moved to Arévalo.[2][6]

These were times of turmoil for Isabella. The living conditions at their castle in Arévalo were poor, and they suffered from a shortage of money. Although her father arranged in his will for his children to be financially well taken care of, King Henry did not comply with their father's wishes, either from a desire to keep his half-siblings restricted, or from ineptitude.[5] Even though living conditions were difficult, under the careful eye of her mother, Isabella was instructed in lessons of practical piety and in a deep reverence for religion.[6]

When the King's wife, Joan of Portugal, was about to give birth to their daughter Joanna, Isabella and her brother Alfonso were summoned to court in Segovia to come under the direct supervision of the King and to finish their education.[2] Alfonso was placed in the care of a tutor while Isabella became part of the Queen's household.[7]

Some of Isabella's living conditions improved in Segovia. She always had food and clothing and lived in a castle that was adorned with gold and silver. Isabella's basic education consisted of reading, spelling, writing, grammar, history, mathematics, art, chess, dancing, embroidery, music, and religious instruction. She and her ladies-in-waiting entertained themselves with art, embroidery, and music. She lived a relaxed lifestyle, but she rarely left Segovia since King Henry forbade this. Her half-brother was keeping her from the political turmoils going on in the kingdom, though Isabella had full knowledge of what was going on and of her role in the feuds.

The noblemen, anxious for power, confronted King Henry, demanding that his younger half-brother Infante Alfonso be named his successor. They even went so far as to ask Alfonso to seize the throne. The nobles, now in control of Alfonso and claiming that he was the true heir, clashed with King Henry's forces at the Second Battle of Olmedo in 1467. The battle was a draw. King Henry agreed to recognize Alfonso as his heir presumptive, provided that he would marry his daughter, Princess Joanna la Beltraneja.[2][8] Soon after he was named Prince of Asturias, Isabella's younger brother Alfonso died in July 1468, likely of the plague. The nobles who had supported him suspected poisoning. As she had been named in her brother's will as his successor, the nobles asked Isabella to take his place as champion of the rebellion.[2] However, support for the rebels had begun to wane, and Isabella preferred a negotiated settlement to continuing the war.[9] She met with her elder brother Henry at Toros de Guisando and they reached a compromise: the war would stop, King Henry would name Isabella his heir-presumptive instead of his daughter Joanna, and Isabella would not marry without her brother's consent, but he would not be able to force her to marry against her will.[2][10] Isabella's side came out with most of what the nobles desired, though they did not go so far as to officially depose King Henry; they were not powerful enough to do so, and Isabella did not want to jeopardize the principle of fair inherited succession, since it was upon this idea that she had based her argument for legitimacy as heir-presumptive.

Marriage

The question of Isabella's marriage was not a new one. She had made her debut in the matrimonial market at the age of six with a betrothal to Ferdinand, the younger son of John II of Navarre (whose family was a cadet branch of the House of Trastámara). At that time, the two kings, Henry and John, were eager to show their mutual love and confidence and they believed that this double alliance would make their eternal friendship obvious to the world.[11] This arrangement, however, did not last long.

Ferdinand's uncle Alfonso V of Aragon died in 1458. All of Alfonso's Spanish territories, as well as the islands of Sicily and Sardinia, were left to his brother John II. John now had a stronger position than ever before and no longer needed the security of Henry's friendship. Henry was now in need of a new alliance. He saw the chance for this much needed new friendship in Charles of Viana, John's elder son.[12] Charles was constantly at odds with his father, and because of this, he secretly entered into an alliance with Henry IV of Castile. A major part of the alliance was that a marriage was to be arranged between Charles and Isabella. When John II learned of this arranged marriage he was outraged. Isabella had been intended for his favourite younger son, Ferdinand, and in his eyes this alliance was still valid. John II had his son Charles thrown in prison on charges of plotting against his father's life; Charles died in 1461.[13]

In 1465, an attempt was made to marry Isabella to Afonso V of Portugal, Henry's brother-in-law.[2] Through the medium of the Queen and Count of Ledesma, a Portuguese alliance was made.[14] Isabella, however, was wary of the marriage and refused to consent.[15]

A civil war broke out in Castile over King Henry's inability to act as sovereign. Henry now needed a quick way to please the rebels of the kingdom. As part of an agreement to restore peace, Isabella was to be betrothed to Pedro Girón Acuña Pacheco, Master of the Order of Calatrava and brother to the King's favourite, Juan Pacheco.[14] In return, Don Pedro would pay into the impoverished royal treasury an enormous sum of money. Seeing no alternative, Henry agreed to the marriage. Isabella was aghast and prayed to God that the marriage would not come to pass. Her prayers were answered when Don Pedro suddenly fell ill and died while on his way to meet his fiancée.[14][16]

When Henry had recognised Isabella as his heir-presumptive on 19 September 1468, he had also promised that his sister should not be compelled to marry against her will, while she in return had agreed to obtain his consent.[2][10] It seemed that finally the years of failed attempts at political marriages were over. There was talk of a marriage to Edward IV of England or to one of his brothers, probably Richard, Duke of Gloucester,[17] but this alliance was never seriously considered.[10] Once again in 1468, a marriage proposal arrived from Afonso V of Portugal. Going against his promises made in September, Henry tried to make the marriage a reality. If Isabella married Afonso, Henry's daughter Joanna would marry Afonso's son John II and thus, after the death of the old king, John and Joanna could inherit Portugal and Castile.[18] Isabella refused and made a secret promise to marry her cousin and very first betrothed, Ferdinand of Aragon.[2]

After this failed attempt, Henry once again went against his promises and tried to marry Isabella to Louis XI's brother Charles, Duke of Berry.[19] In Henry's eyes, this alliance would cement the friendship of Castile and France as well as remove Isabella from Castilian affairs. Isabella once again refused the proposal. Meanwhile, John II of Aragon negotiated in secret with Isabella a wedding to his son Ferdinand.[20]

On 18 October 1469, the formal betrothal took place.[21] Because Isabella and Ferdinand were second cousins, they stood within the prohibited degrees of consanguinity and the marriage would not be legal unless a dispensation from the Pope was obtained.[22] With the help of the Valencian Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia (later Alexander VI), Isabella and Ferdinand were presented with a supposed papal bull by Pius II (who had died in 1464), authorising Ferdinand to marry within the third degree of consanguinity, making their marriage legal.[21] Afraid of opposition, Isabella eloped from the court of Henry with the excuse of visiting her brother Alfonso's tomb in Ávila. Ferdinand, on the other hand, crossed Castile in secret disguised as a servant.[2] They were married immediately upon reuniting, on 19 October 1469, in the Palacio de los Vivero in the city of Valladolid.[23]

War with Portugal

On 12 December 1474, news of Isabella's brother King Henry IV's death in Madrid reached Segovia prompting Isabella to take refuge within the walls of the Alcázar of Segovia where she received the support of Andres de Cabrera and Segovia's council. The next day, Isabella was proclaimed Queen of Castile and León.

Isabella's reign got off to a rocky start. Because her brother had named Isabella as his successor, when she ascended to the throne in 1474, there were already several plots against her. Diego Pacheco, the Marquis of Villena, and his followers maintained that Joanna la Beltraneja, daughter of King Henry IV, was the rightful queen.[24] Shortly after the Marquis made his claim, a longtime supporter of Isabella, the Archbishop of Toledo, left court to plot with his great-nephew the Marquis. The Archbishop and Marquis made plans to have Joanna marry her uncle King Afonso V of Portugal and invade Castile to claim the throne for themselves.[25]

In May 1475, King Afonso and his army crossed into Spain and advanced to Plasencia. Here he married the young Joanna.[26] A long and bloody war for the Castilian succession then took place. The war went back and forth for almost a year until 1 March 1476, when the Battle of Toro took place, a battle in which both sides claimed victory[27][28] and celebrated[28][29] the victory: the troops of King Afonso V were beaten[30][31] by the Castilian centre-left commanded by the Duke of Alba and Cardinal Mendoza while the forces led by John of Portugal defeated[32][33][34][35] the Castilian right wing and remained in possession[36][37] of the battlefield.

But despite its uncertain[38][39] outcome, the Battle of Toro represented a great political victory[40][41][42][43] for the Catholic Monarchs, assuring them the throne since the supporters of Joanna la Beltraneja disbanded and the Portuguese army, without allies, left Castile. As summarised by the historian Justo L. González:

Both armies faced each other at the camps of Toro resulting in an indecisive battle. But while the Portuguese King reorganised his troops, Ferdinand sent news to all the cities of Castile and to several foreign kingdoms informing them about a huge victory where the Portuguese were crushed. Faced with these news, the party of "la Beltraneja" [Joanna] was dissolved and the Portuguese were forced to return to their kingdom.[44]

With great political vision, Isabella took advantage of the moment and convoked courts at Madrigal-Segovia (April–October 1476)[45] where her eldest child and daughter Isabella was first sworn as heiress to Castile's crown. That was equivalent to legitimising Isabella's own throne.

In August of the same year, Isabella proved her abilities as a powerful ruler on her own. A rebellion broke out in Segovia, and Isabella rode out to suppress it, as her husband Ferdinand was off fighting at the time. Going against the advice of her male advisors, Isabella rode by herself into the city to negotiate with the rebels. She was successful and the rebellion was quickly brought to an end.[46] Two years later, Isabella further secured her place as ruler with the birth of her son John, Prince of Asturias, on 30 June 1478. To many, the presence of a male heir legitimised her place as ruler.

Meanwhile, the Castilian and Portuguese fleets fought for hegemony in the Atlantic Ocean and for the wealth of Guinea (gold and slaves), where the decisive naval Battle of Guinea was fought.[47][48]

The war dragged on for another three years[49] and ended with a Castilian victory on land[50] and a Portuguese victory on the sea.[50] The four separate peace treaties signed at Alcáçovas (4 September 1479) reflected that result: Portugal gave up the throne of Castile in favour of Isabella in exchange for a very favourable share of the Atlantic territories disputed with Castile (they all went to Portugal with the exception of the Canary Islands:[51][52] Guinea with its mines of gold, Cape Verde, Madeira, Azores, and the right of conquest over the Kingdom of Fez[53][54]) plus a large war compensation: 106.676 dobles of gold.[55] The Catholic Monarchs also had to accept that Joanna la Beltraneja remain in Portugal instead of Spain[55] and to pardon all rebellious subjects who had supported Joanna and King Afonso.[56] And the Catholic Monarchs—who had proclaimed themselves rulers of Portugal and donated lands to noblemen inside this country[57]—had to give up the Portuguese crown.

At Alcáçovas, Isabella and Ferdinand had conquered the throne, but the Portuguese exclusive right of navigation and commerce in all of the Atlantic Ocean south of the Canary Islands meant that Spain was practically blocked out of the Atlantic and was deprived of the gold of Guinea, which induced anger in Andalusia.[47] Spanish academic Antonio Rumeu de Armas claims that with the peace treaty of Alcáçovas in 1479, the Catholic Monarchs "... buy the peace at an excessively expensive price ..."[58] and historian Mª Monserrat León Guerrero added that they "... find themselves forced to abandon their expansion by the Atlantic ...".[59]

Christopher Columbus freed Castile from this difficult situation, because his New World discovery led to a new and much more balanced sharing of the Atlantic at Tordesillas in 1494. As the orders received by Columbus in his first voyage (1492) show: "[the Catholic Monarchs] have always in mind that the limits signed in the share of Alcáçovas should not be overcome, and thus they insist with Columbus to sail along the parallel of Canary."[59] Thus, by sponsoring the Columbian adventure to the west, the Spanish monarchs were trying the only remaining path of expansion. As is now known, they would be extremely successful on this issue. Isabella had proven herself to be a fighter and tough monarch from the start. Now that she had succeeded in securing her place on the Castilian throne, she could begin to institute the reforms that the kingdom desperately needed.

Regulation of crime

When Isabella came to the throne in 1474, Castile was in a state of despair due to her brother Henry's reign. It was not unknown that Henry IV was a big spender and did little to enforce the laws of his kingdom. It was even said by one Castilian denizen of the time that murder, rape, and robbery happened without punishment.[60] Because of this, Isabella needed desperately to find a way to reform her kingdom. Due to the measures imposed, historians during her lifetime saw her to be more inclined to justice than to mercy, and indeed far more rigorous and unforgiving than her husband Ferdinand.[61]

La Santa Hermandad

Isabella's first major reform came during the cortes of Madrigal in 1476 in the form of a police force, La Santa Hermandad (the Holy Brotherhood). While 1476 was not the first time that Castile had seen the Hermandad, it was the first time that the police force was used by the crown.[62] During the late medieval period, the expression hermandad had been used to describe groups of men who came together of their own accord to regulate law and order by patrolling the roads and countryside and punishing malefactors.[63] These brotherhoods had usually been suppressed by the monarch, however. Before 1476, the justice system in most parts of the country was effectively under the control of dissident members of the nobility rather than royal officials.[64] To fix this problem, during 1476, a general Hermandad was established for Castile, Leon, and Asturias. The police force was to be made up of locals who were to regulate the crime occurring in the kingdom. It was to be paid for by a tax of 1800 maravedís on every one hundred households.[65] In 1477, Isabella visited Extremadura and Andalusia to introduce this more efficient police force there as well.[66]

Other criminal reforms

Keeping with her reformation of the regulation of laws, in 1481 Isabella charged two officials with restoring peace in Galicia. This turbulent province had been the prey of tyrant nobles since the days of Isabella's father, John II.[67] Robbers infested the highways and oppressed the smaller towns and villages. These officials set off with the Herculean task of restoring peace for the province. The officials were successful. They succeeded in driving over 1,500 robbers from Galicia.[68]

Finances

From the very beginning of her reign, Isabella fully grasped the importance of restoring the Crown's finances. The reign of Henry IV had left the kingdom of Castile in great debt. Upon examination, it was found that the chief cause of the nation's poverty was the wholesale alienation of royal estates during Henry's reign.[69] To make money, Henry had sold off royal estates at prices well below their value. The Cortes of Toledo of 1480 came to the conclusion that the only hope of lasting financial reform lay in a resumption of these alienated lands and rents. This decision was warmly approved by many leading nobles of the court, but Isabella was reluctant to take such drastic measures. It was decided that the Cardinal of Spain would hold an enquiry into the tenure of estates and rents acquired during Henry IV's reign. Those that had not been granted as a reward for services were to be restored without compensation, while those that had been sold at a price far below their real value were to be bought back at the same sum. While many of the nobility were forced to pay large sums of money for their estates, the royal treasury became even richer. Isabella's one stipulation was that there would be no revocation of gifts made to churches, hospitals, or the poor.[70]

Another issue of money was the overproduction of coinage and the abundance of mints in the kingdom. During Henry's reign, the number of mints regularly producing money had increased from just five to 150.[69] Much of the coinage produced in these mints was nearly worthless. During the first year of her reign, Isabella established a monopoly over the royal mints and fixed a legal standard to which the coinage had to approximate. By shutting down many of the mints and taking royal control over the production of money, Isabella restored the confidence of the public in the Crown's ability to handle the kingdom's finances.

Government

Both Isabella and Ferdinand established very few new governmental and administrative institutions in their respective kingdoms. Especially in Castile, the main achievement was to use more effectively the institutions that had existed during the reigns of John II and Henry IV.[71] Historically, the center of the Castilian government had been the royal household, together with its surrounding court. The household was traditionally divided into two overlapping bodies. The first body was made up of household officials, mainly people of the nobility, who carried out governmental and political functions for which they received special payment. The second body was made up of some 200 permanent servants or continos who performed a wide range of confidential functions on behalf of the rulers.[72] By the 1470s, when Isabella began to take a firm grip on the royal administration, the senior offices of the royal household were simply honorary titles and held strictly by the nobility. The positions of a more secretarial nature were often held by senior churchmen. Substantial revenues were attached to such offices and were therefore enjoyed greatly, on an effectively hereditary basis, by the great Castilian houses of nobility. While the nobles held the titles, individuals of lesser breeding did the real work.[73]

Traditionally, the main advisory body to the rulers of Castile was the Royal Council. The council, under the monarch, had full power to resolve all legal and political disputes. The council was responsible for supervising all senior administrative officials, such as the Crown representatives in all of the major towns. It was also the supreme judicial tribunal of the kingdom.[74] In 1480, during the Cortes of Toledo, Isabella made many reforms to the Royal Council. Previously there had been two distinct yet overlapping categories of royal councillor. One formed a group which possessed both judicial and administrative responsibilities. This portion consisted of some bishops, some nobles, and an increasingly important element of professional administrators with legal training known as letrados. The second category of traditional councillor had a less formal role. This role depended greatly on the individuals' political influence and personal influence with the monarch. During Isabella's reign, the role of this second category was completely eliminated.[75] As mentioned previously, Isabella had little care for personal bribes or favours. Because of this, this second type of councillor, usually of the nobility, was only allowed to attend the council of Castile as an observer.

Isabella began to rely more on the professional administrators than ever before. These men were mostly of the bourgeoisie or lesser nobility. The council was also rearranged and it was officially settled that one bishop, three caballeros, and eight or nine lawyers would serve on the council at a time. While the nobles were no longer directly involved in the matters of state, they were welcome to attend the meetings. Isabella hoped by forcing the nobility to choose whether to participate or not would weed out those who were not dedicated to the state and its cause.[76]

Isabella also saw the need to provide a personal relationship between herself as the monarch and her subjects. Therefore, Isabella and Ferdinand set aside a time every Friday during which they themselves would sit and allow people to come to them with complaints. This was a new form of personal justice that Castile had not seen before. The Council of State was reformed and presided over by the King and Queen. This department of public affairs dealt mainly with foreign negotiations, hearing embassies, and transacting business with the Court of Rome. In addition to these departments, there was also a Supreme Court of the Santa Hermandad, a Council of Finance, and a Council for settling purely Aragonese matters.[77] Although Isabella made many reforms that seem to have made the Cortes stronger, in actuality the Cortes lost political power during the reigns of Isabella and Ferdinand. Isabella and her husband moved in the direction of a non-parliamentary government and the Cortes became an almost passive advisory body, giving automatic assent to legislation which had been drafted by the royal administration.[78]

After the reforms of the Cortes of Toledo, the Queen ordered a noted jurist, Alfonso Diaz de Montalvo, to undertake the task of clearing away legal rubbish and compiling what remained into a comprehensive code. Within four years the work stood completed in eight bulky volumes and the Ordenanzas Reales took their place on legal bookshelves.[79]

Granada

At the end of the Reconquista, only Granada was left for Isabella and Ferdinand to conquer. The Emirate of Granada had been held by the Muslim Nasrid dynasty since the mid-13th century.[80] Protected by natural barriers and fortified towns, it had withstood the long process of the reconquista. On 1 February 1482, the king and queen reached Medina del Campo and this is generally considered the beginning of the war for Granada. While Isabella's and Ferdinand's involvement in the war was apparent from the start, Granada's leadership was divided and never able to present a united front.[81] It still took ten years to conquer Granada, however, culminating in 1492.

The Spanish monarchs recruited soldiers from many European countries and improved their artillery with the latest and best cannons.[82] Systematically, they proceeded to take the kingdom piece by piece. In 1485 they laid siege to Ronda, which surrendered after only a fortnight due to extensive bombardment.[83] The following year, Loja was taken, and again Muhammad XII was captured and released. One year later, with the fall of Málaga, the western part of the Muslim Nasrid kingdom had fallen into Spanish hands. The eastern province succumbed after the fall of Baza in 1489. The siege of Granada began in the spring of 1491 and at the end of the year, Muhammad XII surrendered. On 2 January 1492 Isabella and Ferdinand entered Granada to receive the keys of the city, and the principal mosque was reconsecrated as a church.[84] The Treaty of Granada was signed later that year, and in it Ferdinand and Isabella gave their word to allow the Muslims and Jews of Granada to live in peace.

During the war, Isabella noted the abilities and energy of Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba and made him one of the two commissioners for the negotiations. Under her patronage, De Córdoba went on to an extraordinary military career that revolutionised the organisation and tactics of the emerging Spanish military, changing the nature of warfare and altering the European balance of power.

Columbus and Portuguese relations

Just three months after entering Granada, Queen Isabella agreed to sponsor Christopher Columbus on an expedition to reach the East Indies by sailing west (2000 miles, according to Columbus).[85] The crown agreed to pay a sum of money as a concession from monarch to subject.[86]

Columbus's expedition departed on 3 August 1492, and arrived in the New World on 12 October.[86] He returned the next year and presented his findings to the monarchs, bringing natives and gold under a hero's welcome. Although Columbus was sponsored by the Castilian queen, treasury accounts show no royal payments to him until 1493, after his first voyage was complete.[87] Spain entered a Golden Age of exploration and colonisation, the period of the Spanish Empire. In 1494, by the Treaty of Tordesillas, Isabella and Ferdinand agreed to divide the Earth, outside of Europe, with King John II of Portugal. The Portuguese did not recognise that South America belonged to the Spanish because it was in Portugal's sphere of influence, and King John II threatened to send an army to claim the land for the Portuguese.

Position on slavery

Isabella was not in favour of enslavement of the American natives and established the royal position on how American indigenous should be treated. She followed the recent policies of the Canaries, that had a small amount of native inhabitants, upon the "New World", stating that all peoples were under the subject of the Castilian Crown and could not be enslaved in most situations. By that time there were some circumstances in which a person could be enslaved, i.e. captured enemy fighters.[88]

After an episode in which Columbus captured 1,200 men, Isabella ordered their return and the arrest of Columbus, who was insulted in the streets of Granada. Isabella realized that she could not trust all the conquest and evangelization to take place through one man, so she opened the range for other expeditions led by Alonso de Hojeda, Juan de la Cosa, Vicente Yáñez Pinzón, Diego de Lepe or Pedro Alonso Niño.[89]

To prevent her efforts from being reversed in the future, in her last will, Isabella instructed her descendants: "do not give rise to or allow the Indians [indigenous Americans] to receive any wrong in their persons and property, but rather that they be treated well and fairly, and if they have received any wrong, remedy it."[90][91]

Expulsion of the Jews

With the institution of the Roman Catholic Inquisition in Spain, and with the Dominican friar Tomás de Torquemada as the first Inquisitor General, the Catholic Monarchs pursued a policy of religious and national unity. Though Isabella opposed taking harsh measures against Jews on economic grounds, Torquemada was able to convince Ferdinand. On 31 March 1492, the Alhambra decree for the expulsion of the Jews was issued.[92] The Jews had until the end of July, four months, to leave the country and they were not to take with them gold, silver, money, arms, or horses.[92] Traditionally, it had been claimed that as many as 200,000 Jews left Spain, but recent historians have shown that such figures are exaggerated: Henry Kamen has shown that out of a total population of 80,000 Jews, a maximum of 40,000 left and the rest converted.[93] Hundreds of those that remained came under the Inquisition's investigations into relapsed conversos (Marranos) and the Judaizers who had been abetting them.[94]

Later years

Isabella received the title of Catholic Monarch by Pope Alexander VI, whose behavior and involvement in matters Isabella did not approve of. Along with the physical unification of Spain, Isabella and Ferdinand embarked on a process of spiritual unification, trying to bring the country under one faith (Roman Catholicism). As part of this process, the Inquisition became institutionalised. After a Muslim uprising in 1499, and further troubles thereafter, the Treaty of Granada was broken in 1502, and Muslims were ordered to either become Christians or to leave. Isabella's confessor, Cisneros, was named Archbishop of Toledo.[95] He was instrumental in a program of rehabilitation of the religious institutions of Spain, laying the groundwork for the later Counter-Reformation. As Chancellor, he exerted more and more power.

Isabella and her husband had created an empire and in later years were consumed with administration and politics; they were concerned with the succession and worked to link the Spanish crown to the other rulers in Europe. By early 1497, all the pieces seemed to be in place: The son and heir John, Prince of Asturias, married a Habsburg princess, Margaret of Austria, establishing the connection to the Habsburgs. The eldest daughter, Isabella of Aragon, married King Manuel I of Portugal, and the younger daughter, Joanna of Castile, was married to a Habsburg prince, Philip I of Habsburg. In 1500, Isabella granted all non-rebellious natives in the colonies citizenship and full legal freedom by decree.[96]

However, Isabella's plans for her eldest two children did not work out. Her only son, John of Asturias, died shortly after his marriage. Her daughter, Isabella of Aragon, died during the birth of her son, Miguel da Paz, who passed away shortly after, at the age of two. Queen Isabella I's crowns passed to her third child, Joanna, and her son-in-law, Philip I.[97]

Isabella did, however, make successful dynastic matches for her two youngest daughters. The death of Isabella of Aragon created a necessity for Manuel I of Portugal to remarry, and Isabella's third daughter, Maria of Aragon, became his next bride. Isabella's youngest daughter, Catherine of Aragon, married England's Arthur, Prince of Wales, but his early death resulted in her being married to his younger brother, King Henry VIII of England.

Isabella officially withdrew from governmental affairs on 14 September 1504 and she died that same year on 26 November at the Medina del Campo Royal Palace. She had already been in decline since the deaths of her son Prince John of Asturias in 1497, her mother Isabella of Portugal in 1496, and her daughter Princess Isabella of Asturias in 1498.[98] She is entombed in Granada in the Capilla Real, which was built by her grandson, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (Carlos I of Spain), alongside her husband Ferdinand, her daughter Joanna and Joanna's husband Philip I; and Isabella's 2-year-old grandson, Miguel da Paz (the son of Isabella's daughter, also named Isabella, and King Manuel I of Portugal).[2] The museum next to the Capilla Real holds her crown and scepter.

Appearance and personality

Isabella was short but of strong stocky build, of a very fair complexion, and had a hair color that was between strawberry-blonde and auburn. Some portraits, however, show her as a brunette.[2] Her daughters, Joanna and Catherine, were thought to resemble her the most. Isabella maintained an austere, temperate lifestyle, and her religious spirit influenced her the most in life. In spite of her hostility towards the Muslims in Andalusia, Isabella developed a taste for Moorish decor and style. Of her, contemporaries said:

- Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés: "To see her speak was divine."[99][100]

- Andrés Bernáldez: "She was an endeavored woman, very powerful, very prudent, wise, very honest, chaste, devout, discreet, truthful, clear, without deceit. Who could count the excellences of this very Catholic and happy Queen, always very worthy of praises."[101][102]

- Hernando del Pulgar: "She was very inclined to justice, so much so that she was reputed to follow more the path of rigor than that of mercy, and did so to remedy the great corruption of crimes that she found in the kingdom when she succeeded to the throne."[103]

- Lucio Marineo Sículo: "[The royal knight Álvaro Yáñez de Lugo] was condemned to be beheaded, although he offered forty thousand ducados for the war against the Moors to the court so that these monies spare his life. This matter was discussed with the queen, and there were some who told her to pardon him, since these funds for the war were better than the death of that man, and her highness should take them. But the queen, preferring justice to cash, very prudently refused them; and although she could have confiscated all his goods, which were many, she did not take any of them to avoid any note of greed, or that it be thought that she had not wished to pardon him in order to have his goods; instead, she gave them all to the children of the aforesaid knight."[104]

- Ferdinand, in his testament, declared that "she was exemplary in all acts of virtue and of fear of God."

- Fray Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros, her confessor and the Grand Inquisitor, praised "her purity of heart, her big heart and the grandness of her soul".

Family

Isabella and Ferdinand had seven children, five of whom survived to adulthood:

- Isabella (1470–1498) married firstly to Afonso, Prince of Portugal, no issue. Married secondly to Manuel I of Portugal, no surviving issue.

- A son, miscarried on 31 May 1475 in Cebreros

- John (1478–1497), Prince of Asturias. Married Archduchess Margaret of Austria, no surviving issue.

- Joanna (1479–1555), Queen of Castile. Married Philip the Handsome, had issue.

- Maria (1482–1517), married Manuel I of Portugal, her sister's widower, had issue.

- A daughter, stillborn twin sister of Maria.[105] Born on 1 July 1482 at dawn.

- Catherine (1485–1536), married firstly to Arthur, Prince of Wales, no issue. Married his younger brother, Henry VIII of England and was mother of Mary I of England.

Towards the end of her life, family tragedies overwhelmed her, although she met these reverses with grace and fortitude . The death of her beloved son and heir and the miscarriage of his wife, the death of her daughter Isabella and Isabella's son Miguel (who could have united the kingdoms of the Catholic Monarchs with that of Portugal), the rebellion and alleged madness of her daughter Joanna and the indifference of Philip the Handsome, and the uncertainty Catherine was in after the death of her husband submerged her in profound sadness that made her dress in black for the rest of her lifetime . Her strong spirituality is well understood from the words she said after hearing of her son's death: "The Lord gave him to me, the Lord hath taken him from me, glory be His holy name."

Sanctity

In 1958, the Catholic canonical process of the Cause of Canonization of Isabella was started by José García Goldaraz, the Bishop of Valladolid, where she died in 1504. 17 experts were appointed to investigate more than 100,000 documents in the archives of Spain and the Vatican and the merits of opening a canonical process of canonisation. 3,500 of these were chosen to be included in 27 volumes.

In 1970, the Commission determined that "A Canonical process for the canonization of Isabella the Catholic could be undertaken with a sense of security since there was not found one single act, public or private, of Queen Isabella that was not inspired by Christian and evangelical criteria; moreover there was a 'reputation of sanctity' uninterrupted for five centuries and as the investigation was progressing, it was more accentuated."

In 1972, the Process of Valladolid was officially submitted to the Congregation for the Causes of Saints in the Vatican. This process was approved and Isabel was given the title "Servant of God" in March 1974.[106]

Some authors have claimed that Isabella's reputation for sanctity derives in large measure from an image carefully shaped and disseminated by the queen herself.[107]

Arms

As Princess of Asturias, Isabella bore the undifferenced royal arms of the Crown of Castile and added the Saint John the Evangelist's Eagle, an eagle displayed as single supporter.[108][109] As queen, she quartered the Royal Arms of the Crown of Castile with the Royal Arms of the Crown of Aragon, she and Ferdinand II of Aragon adopted a yoke and a bundle of arrows as heraldic badges. As co-monarchs, Isabella and Ferdinand used the motto "Tanto Monta" ("They amount to the same", or "Equal opposites in balance"), it refers their prenuptial agreement. The conquest of Granada in 1492 was symbolised by the addition enté en point of a quarter with a pomegranate for Granada (in Spanish Granada means pomegranate).[110] There was an uncommon variant with the Saint John the Evangelist's eagle and two lions adopted as Castilian royal supporters by John II, Isabella's father.[111]

.svg.png.webp) Coat of arms as Princess of Asturias

Coat of arms as Princess of Asturias

(1468–1474).svg.png.webp) Coat of arms as queen

Coat of arms as queen

(1474–1492).svg.png.webp) Coat of arms as queen

Coat of arms as queen

(1492–1504).svg.png.webp) Coat of arms as queen with Castilian royal supporters (1492–1504)

Coat of arms as queen with Castilian royal supporters (1492–1504) Coat of arms of Isabella I of Castile depicted in the manuscript from 1495 Breviary of Isabella the Catholic

Coat of arms of Isabella I of Castile depicted in the manuscript from 1495 Breviary of Isabella the Catholic

Legacy

Isabella is most remembered for enabling Columbus' voyage to the New World, which began an era for greatness for Spain and Europe. In particular her reign saw the founding of the Spanish Empire. This in turn ultimately led to establishment of the modern nations of the Americas.

She and her husband completed the Reconquista, driving out the most significant Muslim influence in Western Europe and firmly establishing Spain and the Iberian peninsula as staunchly Catholic. Her reign also established the Spanish Inquisition.[2]

Commemoration

_-_Memorial_JK_-_Brasilia_-_DSC00387.JPG.webp)

The Spanish crown created the Order of Isabella the Catholic in 1815 in honor of the queen.

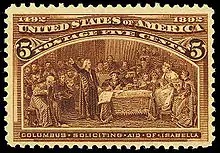

Isabella was the first woman to be featured on US postage stamps,[112] namely on three stamps of the Columbian Issue, also in celebration of Columbus. She appears in the 'Columbus soliciting aid of Isabella', 5-cent issue, and on the Spanish court scene replicated on the 15-cent Columbian, and on the $4 issue, in full portrait, side by side with Columbus.

The $4 stamp is the only stamp of that denomination ever issued and one which collectors prize not only for its rarity (only 30,000 were printed) but its beauty, an exquisite carmine with some copies having a crimson hue. Mint specimens of this commemorative have been sold for more than $20,000.[113] Isabella was also the first named woman to appear on a United States coin, the 1893 commemorative Isabella quarter, celebrating the 400th anniversary of Columbus's first voyage.

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Isabella I of Castile |

|---|

Notes

- Philippa of Lancaster was the daughter John of Gaunt by his first wife, Blanche of Lancaster,[118] making her half-sister of Isabella I of Castille's paternal grandmother, Catherine of Lancaster, who was daughter of the same John of Gaunt but by his second wife, Constance of Castile.

References

- Gristwood, Sarah (2016). Game of Queens: The Women Who Made Sixteenth-Century Europe. Basic Books. p. 30. ISBN 9780465096794.

- Palos, Joan-Lluís (28 March 2019). "To seize power in Spain, Queen Isabella had to play it smart: Bold, strategic, and steady, Isabella of Castile navigated an unlikely rise to the throne and ushered in a golden age for Spain". National Geographic History Magazine. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- Cristina Guardiola-Griffiths. (2018). Isabel I, Queen of Castile. Retrieved from http://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780195399301/obo-9780195399301-0395.xml/.

- Weissberger,Barbara, "Queen Isabel I of Castile Power, Patronage, Persona." Tamesis, Woodbridge, 2008, p. 20–21

- Prescott, William. History of the Reign of Ferdinand and Isabella, The Catholic. J.B Lippincott & Co., 1860, p. 28

- Prescott, William. History of the Reign of Ferdinand and Isabella, The Catholic. J.B Lippincott & CO., 1860, p. 83

- Plunkett, Ierne. Isabel of Castile. The Knickerbocker Press, 1915, p. 52

- Prescott, William. History of the Reign of Ferdinand and Isabella, The Catholic. J.B Lippincott & CO., 1860, p. 85–87

- Prescott, William. History of the Reign of Ferdinand and Isabella, The Catholic. J.B Lippincott & CO., 1860, p. 93–94

- Plunkett, Ierne. Isabel of Castile. The Knickerbocker Press, 1915, p. 68

- Plunkett,Ierne. Isabel of Castile. The Knickerbocker Press, 1915, p. 35

- Plunkett,Ierne. Isabel of Castile. The Knickerbocker Press, 1915, p. 36–39

- Plunkett,Ierne. Isabel of Castile. The Knickerbocker Press, 1915, p. 39-40

- Edwards,John. The Spain of the Catholic Monarchs 1474–1520. Blackwell Publishers Inc, 2000, p. 5

- Plunkett,Ierne. Isabel of Castile. The Knickerbocker Press, 1915, p. 53

- Plunkett,Ierne. Isabel of Castile. The Knickerbocker Press, 1915, p. 62–63

- Edwards,John. The Spain of the Catholic Monarchs 1474–1520. Blackwell Publishers Inc, 2000, p. 9

- Plunkett,Ierne. Isabel of Castile. The Knickerbocker Press, 1915, p. 70–71

- Plunkett,Ierne. Isabel of Castile. The Knickerbocker Press, 1915, p. 72

- Edwards,John. The Spain of the Catholic Monarchs 1474–1520. Blackwell Publishers Inc, 2000, pp. 10,13–14

- Plunkett,Ierne. Isabel of Castile. The Knickerbocker Press, 1915, p. 78

- Edwards,John. The Spain of the Catholic Monarchs 1474–1520. Blackwell Publishers Inc, 2000, pp. 11,13

- Gerli, p. 219

- Plunkett,Ierne. Isabel of Castile. The Knickerbocker Press, 1915, p. 93

- Plunkett,Ierne. Isabel of Castile. The Knickerbocker Press, 1915, p. 96

- Plunkett,Ierne. Isabel of Castile. The Knickerbocker Press, 1915, p. 98

- ↓ Spanish historian Ana Carrasco Manchado: "...The battle [of Toro] was fierce and uncertain, and because of that both sides attributed themselves the victory. John, the son of Afonso of Portugal, sent letters to the Portuguese cities declaring victory. And Ferdinand of Aragon did the same. Both wanted to take advantage of the victory's propaganda." In Isabel I de Castilla y la sombra de la ilegitimidad: propaganda y representación en el conflicto sucesorio (1474–1482), 2006, p. 195, 196.

- ↓ Spanish historian Cesáreo Fernández Duro: "...For those who ignore the background of these circumstances it will certainly seem strange that while the Catholic Monarchs raised a temple in Toledo in honour of the victory that God granted them on that occasion, the same fact [the Battle of Toro] was festively celebrated with solemn processions on its anniversary in Portugal" in La batalla de Toro (1476). Datos y documentos para su monografía histórica, in Boletín de la Real Academia de la Historia, tome 38, Madrid, 1901,p. 250.

- ↓ Manchado, Isabel I de Castilla y la sombra de la ilegitimidad: propaganda y representación en el conflicto sucesorio (1474–1482), 2006, p. 199 (foot note nr.141).

- ↓ Pulgar, Crónica de los Señores Reyes Católicos Don Fernando y Doña Isabel de Castilla y de Aragón, chapter XLV.

- ↓ Garcia de Resende- Vida e feitos d'El Rei D.João II, chapter XIII.

- ↓ chronicler Hernando del Pulgar (Castilian): "...promptly, those 6 Castilian captains, which we already told were at the right side of the royal battle, and were invested by the prince of Portugal and the bishop of Évora, turned their backs and put themselves on the run." in Crónica de los Señores Reyes Católicos Don Fernando y Doña Isabel de Castilla y de Aragón, chapter XLV.

- ↓ chronicler Garcia de Resende (Portuguese): "... And being the battles of both sides ordered that way and prepared to attack by nearly sunshine, the King ordered the prince to attack the enemy with his and God's blessing, which he obeyed (...). (...) and after the sound of the trumpets and screaming all for S. George invested so bravely the enemy battles, and in spite of their enormous size, they could not stand the hard fight and were rapidly beaten and put on the run with great losses." In Vida e feitos d'El Rei D.João II, chapter XIII.

- ↓ chronicler Juan de Mariana (Castilian): "(...) the [Castilian] horsemen (...) moved forward(...).They were received by prince D. John... which charge... they couldn't stand but instead were defeated and ran away " in Historia General de España, tome V, book XXIV, chapter X, p. 299,300.

- ↓ chronicler Damião de Góis (Portuguese): "(...)these Castilians who were on the right of the Castilian Royal battle, received [the charge of] the Prince's men as brave knights invoking Santiago but they couldn't resist them and began to flee, and [so] our men killed and arrested many of them, and among those who escaped some took refuge (...) in their Royal battle that was on left of these six [Castilian] divisions. " in Chronica do Principe D. Joam, chapter LXXVIII.

- ↓ chronicler Juan de Mariana (Castilian): "...the enemy led by prince D. John of Portugal, who without suffering defeat, stood on a hill with his forces in good order until very late (...). Thus, both forces [Castilian and Portuguese] remained face to face for some hours; and the Portuguese kept their position during more time (...)" in Historia General de España, tome V, book XXIV, chapter X, p. 299,300.

- ↓ chronicler Rui de Pina (Portuguese): "And being the two enemy battles face to face, the Castilian battle was deeply agitated and showing clear signs of defeat if attacked as it was without King and dubious of the outcome.(...) And without discipline and with great disorder they went to Zamora. So being the Prince alone on the field without suffering defeat but inflicting it on the adversary he became heir and master of his own victory" in Chronica de El- rei D.Affonso V... 3rd book, chapter CXCI.

- ↓ French historian Jean Dumont in La "imcomparable" Isabel la Catolica/ The incomparable Isabel the Catholic, Encuentro Ediciones, printed by Rogar-Fuenlabrada, Madrid, 1993 (Spanish edition), p. 49: "...But in the left [Portuguese] Wing, in front of the Asturians and Galician, the reinforcement army of the Prince heir of Portugal, well provided with artillery, could leave the battlefield with its head high. The battle resulted this way, inconclusive. But its global result stays after that decided by the withdrawal of the Portuguese King, the surrender... of the Zamora's fortress on 19 March, and the multiple adhesions of the nobles to the young princes."

- ↓ French historian Joseph-Louis Desormeaux: "... The result of the battle was very uncertain; Ferdinand defeated the enemy's right wing led by Afonso, but the Prince had the same advantage over the Castilians." In Abrégé chronologique de l'histoire de l'Éspagne, Duchesne, Paris, 1758, 3rd Tome, p. 25.

- ↓ Spanish academic António M. Serrano: " From all of this it is deductible that the battle [of Toro] was inconclusive, but Isabella and Ferdinand made it fly with wings of victory. (...) Actually, since this battle transformed in victory; since 1 March 1476, Isabella and Ferdinand started to rule in the Spain's throne. (...) The inconclusive wings of the battle became the secure and powerful wings of San Juan's eagle [the commemorative temple of the Battle of Toro] ." in San Juan de los Reyes y la batalla de Toro, revista Toletum Archived 12 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, segunda época, 1979 (9), pp. 55–70. Real Academia de Bellas Artes y Ciencias Históricas de Toledo, Toledo. ISSN: 0210-6310 Archived 30 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ↓ A. Ballesteros Beretta: "His moment is the inconclusive Battle of Toro.(...) both sides attributed themselves the victory.... The letters written by the King [Ferdinand] to the main cities... are a model of skill. (...) what a powerful description of the battle! The nebulous transforms into light, the doubtful acquires the profile of a certain triumph. The politic [Ferdinand] achieved the fruits of a discussed victory." In Fernando el Católico, el mejor rey de España, Ejército revue, nr 16, p. 56, May 1941.

- ↓ Vicente Álvarez Palenzuela- La guerra civil Castellana y el enfrentamiento con Portugal (1475–1479): "That is the battle of Toro. The Portuguese army had not been exactly defeated, however, the sensation was that D. Juana's cause had completely sunk. It made sense that for the Castilians Toro was considered as the divine retribution, the compensation desired by God to compensate the terrible disaster of Aljubarrota, still alive in the Castilian memory".

- ↓ Spanish academic Rafael Dominguez Casas: "...San Juan de los Reyes resulted from the royal will to build a monastery to commemorate the victory in a battle with an uncertain outcome but decisive, the one fought in Toro in 1476, which consolidated the union of the two most important Peninsular Kingdoms." In San Juan de los reyes: espacio funerário y aposento régio in Boletín del Seminário de Estúdios de Arte y Arqueologia, number 56, p. 364, 1990.

- ↓ Justo L. González- Historia del Cristianismo Archived 16 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Editorial Unilit, Miami, 1994, Tome 2, Parte II (La era de los conquistadores), p. 68.

- ↓ Historian Marvin Lunenfeld: "In 1476, immediately after the indecisive battle of Peleagonzalo [near Toro], Ferdinand and Isabella hailed the result as a great victory and called a cortes at Madrigal. The newly created prestige was used to gain municipal support from their allies(...)" in The council of the Santa Hermandad: a study of the pacification forces of Ferdinand and Isabella, University of Miami Press, 1970, p. 27.

- Prescott, William. History of the Reign of Ferdinand and Isabella, The Catholic. J.B. Lippincott & CO., 1860, p. 184–185

- Battle of Guinea: ↓ Alonso de Palencia, Década IV, Book XXXIII, Chapter V ("Disaster among those sent to the mines of gold [Guinea]. Charges against the King..."), pp. 91–94. This was a decisive battle because after it, in spite of the Catholic Monarchs' attempts, they were unable to send new fleets to Guinea, Canary or to any part of the Portuguese empire until the end of the war. The Perfect Prince sent an order to drown any Castilian crew captured in Guinea waters. Even the Castilian navies which left Guinea before the signature of the peace treaty had to pay the tax ("quinto") to the Portuguese crown when they returned to Castile after the peace treaty. Isabella had to ask permission of Afonso V so that this tax could be paid in Castilian harbours. Naturally all this caused a grudge against the Catholic Monarchs in Andalusia.

- ↓ Historian Malyn Newitt: "However, in 1478 the Portuguese surprised thirty-five Castilian ships returning from Mina [Guinea] and seized them and all their gold. Another...Castilian voyage to Mina, that of Eustache de la Fosse, was intercepted ... in 1480. (...) All things considered, it is not surprising that the Portuguese emerged victorious from this first maritime colonial war. They were far better organised than the Castilians, were able to raise money for the preparation and supply of their fleets, and had clear central direction from ... [Prince] John." In A history of Portuguese overseas expansion, 1400–1668, Routledge, New York, 2005, pp. 39–40.

- Plunkett,Ierne. Isabel of Castile The Knickerbocker Press, 1915, p. 109–110

- ↓ Bailey W. Diffie and George D. Winius "In a war in which the Castilians were victorious on land and the Portuguese at sea, ..." in Foundations of the Portuguese empire 1415–1580, volume I, University of Minnesota Press, 1985, p. 152.

- ↓ Alonso de Palencia, Decada IV, book XXXII, chapter III: in 1478 a Portuguese fleet intercepted the armada of 25 navies sent by Ferdinand to conquer Gran Canary – capturing 5 of its navies plus 200 Castilians – and forced it to fled hastily and definitively from Canary waters. This victory allowed Prince John to use the Canary Islands as an "exchange coin" in the peace treaty of Alcáçovas.

- ↓ Pina, Chronica de El-Rei D. Affonso V, 3rd book, chapter CXCIV (Editorial error: Chapter CXCIV erroneously appears as Chapter CLXIV.Reports the end of the siege of Ceuta by the arrival of the fleet with Afonso V).

- ↓ Quesada, Portugueses en la frontera de Granada, 2000, p. 98. In 1476 Ceuta was simultaneously besieged by the moors and a Castilian army led by the Duke of Medina Sidónia. The Castilians conquered the city from the Portuguese who took refuge in the inner fortress, but a Portuguese fleet arrived "in extremis" and regained the city. A Ceuta dominated by the Castilians would certainly have forced the right to conquer Fez (Morocco) to be shared between Portugal and Castile instead of the monopoly the Portuguese acquired.

- ↓ Mendonça, 2007, p. 101–103.

- Edwards,John. The Spain of the Catholic Monarchs 1474–1520. Blackwell Publishers Inc, 2000, p. 38

- ↓ Mendonça, 2007, p. 53.

- ↓ António Rumeu de Armas- book description, MAPFRE, Madrid, 1992, page 88.

- ↓ Mª Monserrat León Guerrero in El segundo viaje colombino, University of Valladolid, 2000, chapter 2, pp. 49–50.

- Plunkett,Ierne. Isabel of Castile. The Knickerbocker Press, 1915, p. 121

- Boruchoff, David A. "Historiography with License: Isabel, the Catholic Monarch, and the Kingdom of God." Isabel la Católica, Queen of Castile: Critical Essays. Palgrave Macmillan, 2003, pp. 242–247.

- Plunkett,Ierne. Isabel of Castile. The Knickerbocker Press, 1915, p. 125

- Edwards,John. The Spain of the Catholic Monarchs 1474–1520. Blackwell Publishers Inc, 2000, p. 42

- Edwards,John. The Spain of the Catholic Monarchs 1474–1520. Blackwell Publishers Inc, 2000, pp. 48–49

- Plunkett,Ierne. Isabel of Castile. The Knickerbocker Press, 1915, p. 125-126

- Prescott, William. History of the Reign of Ferdinand and Isabella, The Catholic. J.B Lippincott & CO., 1860, p. 186

- Plunkett,Ierne. Isabel of Castile. The Knickerbocker Press, 1915, p. 123

- Plunkett,Ierne. Isabel of Castile. The Knickerbocker Press, 1915, p. 133

- Plunkett,Ierne. Isabel of Castile. The Knickerbocker Press, 1915, p. 150

- Plunkett,Ierne. Isabel of Castile. The Knickerbocker Press, 1915, p. 152–155

- Edwards, John. Ferdinand and Isabella. Pearson Education Limited, 2005, p. 28

- Edwards, John. Ferdinand and Isabella. Pearson Education Limited, 2005, p. 29

- Edwards, John. Ferdinand and Isabella. Pearson Education Limited, 2005, p. 29–32

- Edwards, John. Ferdinand and Isabella. Pearson Education Limited, 2005, p. 30

- Edwards,John. The Spain of the Catholic Monarchs 1474–1520. Blackwell Publishers Inc, 2000, p. 42–47

- Plunkett, Ierne. Isabella of Castile. The Knickerbocker Press, 1915, p. 142

- Plunkett,Ierne. Isabel of Castile. The Knickerbocker Press, 1915, p. 143

- Edwards,John. The Spain of the Catholic Monarchs 1474–1520. Blackwell Publishers Inc, 2000, p. 49

- Plunkett,Ierne. Isabel of Castile. The Knickerbocker Press, 1915, p. 146

- Edwards, John. Ferdinand and Isabella. Pearson Education Limited, 2005, p. 48

- Edwards, John. Ferdinand and Isabella. Pearson Education Limited, 2005, p. 48–49

- Edwards,John. The Spain of the Catholic Monarchs 1474–1520. Blackwell Publishers Inc, 2000, p. 104–106

- Edwards,John. The Spain of the Catholic Monarchs 1474–1520. Blackwell Publishers Inc, 2000, p. 111

- Edwards,John. The Spain of the Catholic Monarchs 1474–1520. Blackwell Publishers Inc, 2000, p. 112–130

- Liss,Peggy. "Isabel the Queen," Oxford University Press, 1992. p. 316

- Edwards, John. Ferdinand and Isabella. Pearson Education Limited, 2005, p. 120

- Edwards, John. Ferdinand and Isabella. Pearson Education Limited, 2005, p. 119

- F. Weissberger, Barbara Queen Isabel I of Castile: Power, Patronage, Persona, Tamesis Books, 2008, p. 27, accessed 9 July 2012

- https://www.abc.es/historia/abci-batallo-isabel-catolica-indios-fueran-tratados-bien-y-carino-202006172253_noticia.html#vca=rrss-inducido&vmc=abc-es&vso=tw&vli=noticia-foto

- https://es.wikisource.org/wiki/Testamento_de_Isabel_la_Cat%C3%B3lica

- https://www.abc.es/sociedad/20130303/abci-leyes-indias-derechos-humanos-201303012122.html

- Liss,Peggy. "Isabel the Queen," Oxford University Press, 1992. p. 298

- Henry Kamen, The Spanish Inquisition: A Historical Revision. (Yale University Press, 1997. pp. 29–31).

- Liss,Peggy. "Isabel the Queen," Oxford University Press, 1992. p. 308

- Hunt, Jocelyn. Spain 1474–1598. Routledge, 2001, p. 20

- Beezley, William H.; Beezley, William; Meyer, Michael (3 August 2010). The Oxford History of Mexico. ISBN 9780199731985.

- Edwards,John. The Spain of the Catholic Monarchs 1474–1520. Blackwell Publishers Inc, 2000, p. 241–260

- Edwards,John. The Spain of the Catholic Monarchs 1474–1520. Blackwell Publishers Inc, 2000, p. 282

- Bakersfield, Katherine. "Katherine's Reviews > Isabel: Jewel of Castilla, Spain, 1466". Good Reads. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- Meyer, Carolyn (2000). Isabel: Jewel of Castilla. Scholastic. ISBN 9780439078054.

- "Isabella I of Castille". Book of Days Tales. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- John de Aragon, Ray (2012). Hidden History of Spanish New Mexico. Amazon.com: Acradia Publishing. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-1-60949-760-6.

- Pulgar, Crónica de los Reyes Católicos, trans. in David A. Boruchoff, "Historiography with License: Isabel, the Catholic Monarch, and the Kingdom of God," Isabel la Católica, Queen of Castile: Critical Essays (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), p. 242.

- Marineo Sículo, De las cosas memorables de España (1539), trans. in David A. Boruchoff, "Instructions for Sainthood and Other Feminine Wiles in the Historiography of Isabel I," Isabel la Católica, Queen of Castile: Critical Essays (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003), p. 12.

- Peggy K. Liss, Isabel the Queen: Life and Times, (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992), 220.

- http://www.queenisabel.com/Canonisation/CanonicalProcess.html Accessed 8 October 2012

- Boruchoff, David A. "Instructions for Sainthood and Other Feminine Wiles in the Historiography of Isabel I." Isabel la Católica, Queen of Castile: Critical Essays. Palgrave Macmillan, 2003, pp. 1–23.

- Isabel la Católica en la Real Academia de la Historia. Madrid: Real Academia de la Historia. 2004. p. 72. ISBN 978-84-95983-54-1.

- Princess of Isabella's coat of arms with crest: García-Menacho Osset, Eduardo (2010). "El origen militar de los símbolos de España. El escudo de España" [Military Origin of Symbols of Spain. The Coat of Arms of Spain]. Revista de Historia Militar (in Spanish) (Extra): 387. ISSN 0482-5748.

- Menéndez-Pidal De Navascués, Faustino; El escudo; Menéndez Pidal y Navascués, Faustino; O'Donnell, Hugo; Lolo, Begoña. Símbolos de España. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Políticos y Constitucionales, 1999. ISBN 84-259-1074-9

- Image of the Isabella's coat of arms with lions as supporters, facade of the St. Paul Church inValladolid (Spain) Artehistoria. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- Scotts Specialized Catalogue of United States Stamps

- Scotts Specialized Catalogue of United States Stamps:Quantities Issued

- Henry III, King of Castille at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Ferdinand I, King of Aragon at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Leese, Thelma Anna, Blood royal: issue of the kings and queens of medieval England, 1066–1399, (Heritage Books Inc., 1996), 222.

- Lee, Sidney, ed. (1896). . Dictionary of National Biography. 45. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 167.

- Armitage-Smith, Sydney (1905). John of Gaunt: King of Castile and Leon, Duke of Aquitaine and Lancaster, Earl of Derby, Lincoln, and Leicester, Seneschal of England. Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 77. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- Gerli, E. Michael; Armistead, Samuel G. (2003). Medieval Iberia. Taylor & Francis. p. 182. ISBN 9780415939188. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

Further reading

- Boruchoff, David A. Isabel la Católica, Queen of Castile: Critical Essays. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003.

- Diffie, Bailey W. and Winius, George D. (1977) Foundations of the Portuguese Empire, 1415–1580, Volume 1, University of Minnesota Press.

- Downey, Kirsten "Isabella, The Warrior Queen,". New York, Anchor Books, Penguin, 2014.

- Gerli, Edmondo Michael (1992) Medieval Iberia: An Encyclopedia, Taylor & Francis.

- Edwards, John. The Spain of the Catholic Monarchs, 1474–1520. Oxford: Blackwell 2000. ISBN 0-631-16165-1

- Hillgarth, J.N. The Spanish Kingdoms, 1250–1516. Castilian hegemony. Oxford 1978.

- Hunt, Joceyln (2001) Spain, 1474–1598. Routledge, 1st Ed.

- Kamen, Henry. The Spanish Inquisition: a historical revision (Yale University Press, 2014)

- Liss, Peggy K. (1992) Isabel the Queen. New York: Oxford University Press;

- Lunenfeld, Marvin (1970) "The council of the Santa Hermandad: a study of the pacification forces of Ferdinand and Isabella", University of Miami Press. ISBN 978-0870241437

- Miller, Townsend Miller (1963) The Castles and the Crown: Spain 1451–1555. New York: Coward-McCann

- Prescott, William H. (1838). History of the Reig of Ferdinand and Isabella.

- Roth, Norman (1995) Conversos, Inquisition, and the Expulsion of the Jews from Spain. (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press)

- Stuart, Nancy Rubin. Isabella of Castile: the First Renaissance Queen (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1991)

- Tremlett, Giles. '"Isabella of Castile. Europe's First Great Queen"' (London: Bloomsbury, 2017)

- Tremlett, Giles. "Catherine of Aragon. Henry's Spanish Queen" (London: Faber and Faber, 2010)

- Weissberger, Barbara F. Queen Isabel I of Castile: Power, Patronage, Persona (2008)

- Weissberger, Barbara F. Isabel Rules: Constructing Queenship, Wielding Power (2003)

Books

- Armas, Antonio Rumeu (1992) El tratado de Tordesillas. Madrid: Colecciones MAPFRE 1492, book description.

- Azcona, Tarsicio de. Isabel la Católica. Estudio crítico de su vida y su reinado. Madrid 1964.

- Desormeaux, Joseph-Louis Ripault (1758) Abrégé chronologique de l'histoire de l'Éspagne, Duchesne, Paris, 3rd Tome.

- Dumont, Jean (1993) La "imcomparable" Isabel la Catolica (The "incomparable" Isabella, the Catholic), Madrid: Encuentro Editiones, printed by Rogar-Fuenlabrada (Spanish edition).

- González, Justo L. (1994) Historia del Cristianismo, Miami: Editorial Unilit, Tome 2. ISBN 1560634766

- Guerrero, Mª Monserrat León (2002) El segundo viaje colombino, Alicante: Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. ISBN 8468812080

- Ladero Quesada, Miguel Angel. La España de los Reyes Católicos, Madrid 1999.

- Manchado, Ana Isabel Carrasco (2006) Isabel I de Castilla y la sombra de la ilegitimidad. Propaganda y representación en el conflicto sucesorio (1474–1482), Madrid: Sílex ediciones.

- Mendonça, Manuela (2007) O Sonho da União Ibérica – guerra Luso-Castelhana 1475/1479, Lisboa: Quidnovi, book description. ISBN 978-9728998882

- Pereira, Isabel Violante (2001) De Mendo da Guarda a D. Manuel I. Lisboa: Livros Horizonte

- Perez, Joseph. Isabel y Fernando. Los Reyes Católicos. Madrid 1988.

- Suárez Fernández, L. and M. Fernández (1969) La España de los reyes Católicos (1474–1516).

Articles

- Beretta, Antonio Ballesteros (1941) Fernando el Católico, in Ejército revue, Ministerio del Ejercito, Madrid, nr 16, p. 54–66, May 1941.

- Casas, Rafael Dominguez (1990) San Juan de los reyes: espacio funerário y aposento régio – in Boletín del Seminário de Estúdios de Arte y Arqueologia, number 56, p. 364–383, University of Valladolid.

- Duro, Cesáreo Fernández (1901) La batalla de Toro (1476). Datos y documentos para su monografía histórica, Madrid: Boletín de la Real Academia de la Historia, tomo 38.

- Palenzuela,Vicente Ángel Alvarez (2006) La guerra civil castellana y el enfrentamiento con Portugal (1475–1479), Universidad de Alicante, Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes.

- Quesada, Miguel-Ángel Ladero (2000) Portugueses en la frontera de Granada, Revista En la España medieval, Universidad Complutense, nr. 23, pages 67–100.

- Serrano, António Macia- San Juan de los Reyes y la batalla de Toro, revista Toletum, segunda época, 1979 (9), pp. 55–70. Toledo: Real Academia de Bellas Artes y Ciencias Históricas de Toledo. ISSN: 0210-6310

Chronicles

- Góis, Damião de (1724) Chronica do Principe D. Joam, edited by Lisboa occidental at the officina da Música, Lisboa (Biblioteca Nacional Digital).

- Mariana, Juan de (1839) Historia General de España, tome V Barcelona: printing press of D. Francisco Oliva.

- Palencia, Alfonso de – Gesta Hispaniensia ex annalibus suorum diebus colligentis, Década III and IV (the three first Décadas were edited as Cronica del rey Enrique IV by Antonio Paz y Meliá in 1904 and the fourth as Cuarta Década by José Lopes de Toro in 1970).

- Pina, Ruy de (1902) Chronica de El- rei D. Affonso V, Project Gutenberg Ebook, Biblioteca de Clássicos Portugueses, 3rd book, Lisboa.

- Pulgar, Hernando del (1780) Crónica de los Señores Reyes Católicos Don Fernando y Doña Isabel de Castilla y de Aragón, (Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes), Valencia: edited by Benito Monfort.

- Resende, Garcia de – Vida e feitos d'El Rei D.João II electronic version, wikisource.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Isabella of Castile. |

- Isabella I in the Catholic Encyclopedia

- Medieval Sourcebook: Columbus' letter to King and Queen of Spain, 1494

- Music at Isabella's court

- University of Hull: Genealogy information on Isabella I

- El obispo judío que bloquea a la "santa". A report in Spanish about the beatification in El Mundo

- Isabella I of Castile – Facts (Video) | Check123 – Video Encyclopedia

Isabella I of Castile Born: 22 April 1451 Died: 26 November 1504 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Henry IV |

Queen regnant of Castile and León 1474–1504 with Ferdinand V (1475–1504) |

Succeeded by Joanna |

| Spanish royalty | ||

| Vacant Title last held by Juana Enríquez |

Queen consort of Sicily 1469–1504 |

Vacant Title next held by Germaine of Foix |

| Queen consort of Aragon 1479–1504 | ||

| Preceded by Anne of Brittany |

Queen consort of Naples 1504 | |

| Spanish nobility | ||

| Preceded by Alfonso |

Princess of Asturias 1468–1474 |

Succeeded by Isabella |

.svg.png.webp)