Truro

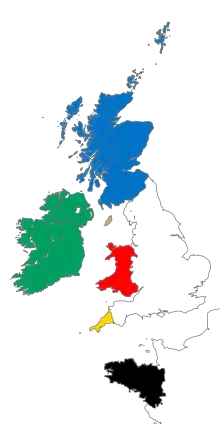

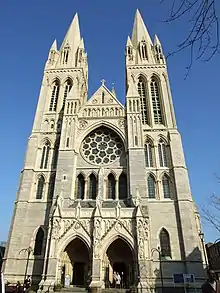

Truro (/ˈtrʊəroʊ/; Cornish: Truru)[2] is a cathedral city and civil parish in Cornwall, England, UK. It is Cornwall's county town and only city, and its centre for administration, leisure and retail. Its population was recorded as 18,766 in the 2011 census.[1] People from Truro are known as Truronians.[3] Truro grew as a trade centre through its port and then as a stannary town for the tin-mining industry. It gained city status in 1876 with the founding of the Diocese of Truro, and so became mainland Britain's southernmost city. Places of interest include the Royal Cornwall Museum, Truro Cathedral (completed in 1910), the Hall for Cornwall and Cornwall's Courts of Justice.

Truro

| |

|---|---|

| City | |

Truro Cathedral overlooking the city | |

Truro Location within Cornwall | |

| Population | 18,766 [1] |

| Demonym | Truronian |

| OS grid reference | SW825448 |

| • London | 232 miles (373 km) ENE |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county |

|

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | TRURO |

| Postcode district | TR1-4 |

| Dialling code | 01872 |

| Police | Devon and Cornwall |

| Fire | Cornwall |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | truro.gov.uk |

Toponymy

The origin of Truro's name is debated. It has been said to derive from the Cornish tri-veru meaning "three rivers", but authorities such as the Oxford Dictionary of English Place Names reject this theory. There are doubts about the "tru" part meaning "three". An expert on Cornish place-names, Oliver Padel, in A Popular Dictionary of Cornish Place-names, called the "three rivers" meaning "possible".[4] Alternatively the name may derive from tre-uro or similar, i. e. the settlement on the river Uro.[5][6]

History

The earliest records and archaeological finds of a permanent settlement in the Truro area date from Norman times. A castle was built there in the 12th century by Richard de Luci, Chief Justice of England in the reign of Henry II, who for his services to the court was granted land in Cornwall, including the area surrounding the confluence of the two rivers. The town grew in the shadow of the castle and was awarded borough status to further economic activity. The castle has long since disappeared.

Richard de Lucy fought in Cornwall under Count Alan of Brittany after leaving Falaise late in 1138. The small adulterine castle at Truro, Cornwall (originally the parish of Kenwyn), later known as "Castellum de Guelon" was probably built by him in 1139–1140. He styled himself "Richard de Lucy, de Trivereu". The castle later passed to Reginald FitzRoy (also known as Reginald de Dunstanville), an illegitimate son of Henry I, when he was invested by King Stephen as the first Earl of Cornwall. Reginald married Mabel FitzRichard, daughter of William FitzRichard, a substantial landholder in Cornwall. The 75-foot (23 m)-diameter castle was in ruins by 1270 and the motte was levelled in 1840. Today Truro Crown Court stands on the site. In a charter of about 1170, Reginald FitzRoy confirmed to the burgesses of Truro the privileges granted by Richard de Lucy. Richard held ten knights' fees in Cornwall prior to 1135 and at his death the county still accounted for a third of his considerable total holding.[7]

By the start of the 14th century Truro was an important port, due to its inland location away from invaders, prosperity from the fishing industry, and a new role as one of Cornwall's stannary towns for assaying and stamping tin and copper from Cornish mines. The Black Death brought a trade recession and an exodus of the population that left the town in a very neglected state. Trade gradually returned and the town regained prosperity in the Tudor period. Local government was awarded in 1589 by a new charter granted by Elizabeth I, giving Truro an elected mayor and control over the port of Falmouth.

During the Civil War in the 17th century, Truro raised a sizeable force to fight for the king and a royalist mint was set up. Defeat by the Parliamentary troops came after the Battle of Naseby in 1646, when the victorious Parliamentarian general Fairfax led his army south-west to relieve Taunton and capture the Royalist-held West Country. The Royalist forces surrendered at Truro while leading Royalist commanders, including Lord Hopton, the Prince of Wales, Sir Edward Hyde, and Lord Capell, fled to Jersey from Falmouth.[8] The mint was moved to Exeter.

Later in the century, Falmouth was awarded its own charter, giving it rights to its harbour and starting a long rivalry between the two towns. The dispute was settled in 1709 with control of the River Fal divided between them. The arms of the city of Truro are "Gules the base wavy of six Argent and Azure, thereon an ancient ship of three masts under sail, on each topmast a banner of St George, on the waves in base two fishes of the second."[9]

Truro prospered in the 18th and 19th centuries. Industry flourished through improved mining methods and higher prices for tin, and the town attracted wealthy mine owners. Elegant Georgian and Victorian townhouses were built, such as those seen today in Lemon Street, named after the mining magnate and local MP Sir William Lemon. Truro became the centre for society in the county, even dubbed "the London of Cornwall".[10]

Throughout those prosperous times Truro remained a social centre, and many notable people came from there. Among the noteworthy were Richard Lander, an explorer who was the first European to reach the mouth of the River Niger in Africa and was awarded the first gold medal of the Royal Geographical Society, and Henry Martyn, who read mathematics at Cambridge, was ordained and became a missionary, translating the New Testament into Urdu and Persian. Others include Humphry Davy, educated in Truro and the inventor of the miner's safety lamp, and Samuel Foote, an actor and playwright from Boscawen Street.

Truro's importance increased later in the 19th century, with an iron-smelting works, potteries, and tanneries. From the 1860s, the Great Western Railway provided a direct link to London Paddington. The Bishopric of Truro Act 1876 gave the town a bishop and later a cathedral. The next year it was granted city status. The New Bridge Street drill hall was completed in the late 19th century.[11]

Mining declined in the early 20th century, but Truro remained prosperous as a developing administrative and commercial centre of Cornwall. Today it remains the county retail centre, but like other places, faces concerns over replacement of speciality shops by national chain stores, erosion of identity, and doubts about how to accommodate growth expected in the 21st century.

Geography

Truro lies in the centre of western Cornwall, about 9 miles (14 kilometres) from the south coast, at the confluence of the rivers Kenwyn and Allen, which combine as the Truro River – one of a series of creeks, rivers and drowned valleys leading into the River Fal and then to the large natural harbour of Carrick Roads. The valleys form a steep-sided bowl surrounding the city on the north, east and west, open to the Truro River in the south. The bowl shape, along with high precipitation that swells the rivers and a spring tide in the River Fal, were major factors in the 1988 floods that seriously damaged the city centre. Since then, flood defences have been constructed, including an emergency dam at New Mill on the River Kenwyn and a tidal barrier on the Truro River.

The city is surrounded by several protected natural areas such as the historic parklands at Pencalenick, and larger areas of ornamental landscape, such as Trelissick Garden and Tregothnan further down the Truro River. An area south-east of the city, around and including Calenick Creek, has been designated an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. Other protected areas include an Area of Great Landscape Value comprising agricultural land and wooded valleys to the north east, and Daubuz Moors, a local nature reserve alongside the River Allen close to the city centre.

Truro has mainly grown and developed around the historic city centre in a nuclear fashion along the slopes of the bowl valley, except for fast linear development along the A390 to the west, towards Threemilestone. As Truro has grown, it has encompassed other settlements as suburbs or districts, including Kenwyn and Moresk to the north, Trelander to the east, Newham to the south, and Highertown, Treliske and Gloweth to the west.

Climate

The Truro area has an oceanic climate similar to the rest of Cornwall's. This means even fewer extremes in temperature than in the remainder of England, marked by high rainfall, cool summers and mild winters with infrequent frosts.

| Climate data for Camborne, elevation: 87 m (285 ft), 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1979–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 15.5 (59.9) |

14.2 (57.6) |

18.0 (64.4) |

21.8 (71.2) |

24.5 (76.1) |

27.7 (81.9) |

29.3 (84.7) |

29.4 (84.9) |

26.0 (78.8) |

23.8 (74.8) |

17.0 (62.6) |

15.3 (59.5) |

29.4 (84.9) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.9 (48.0) |

8.7 (47.7) |

10.1 (50.2) |

11.7 (53.1) |

14.3 (57.7) |

16.7 (62.1) |

18.6 (65.5) |

19.0 (66.2) |

17.3 (63.1) |

14.3 (57.7) |

11.5 (52.7) |

9.6 (49.3) |

13.4 (56.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.8 (44.2) |

6.5 (43.7) |

7.8 (46.0) |

8.9 (48.0) |

11.5 (52.7) |

13.8 (56.8) |

15.8 (60.4) |

16.1 (61.0) |

14.6 (58.3) |

12.0 (53.6) |

9.3 (48.7) |

7.4 (45.3) |

10.9 (51.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 4.6 (40.3) |

4.2 (39.6) |

5.4 (41.7) |

6.1 (43.0) |

8.6 (47.5) |

10.9 (51.6) |

13.0 (55.4) |

13.2 (55.8) |

11.8 (53.2) |

9.6 (49.3) |

7.1 (44.8) |

5.2 (41.4) |

8.3 (46.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −9.4 (15.1) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−3.2 (26.2) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

0.3 (32.5) |

4.8 (40.6) |

7.2 (45.0) |

7.4 (45.3) |

4.8 (40.6) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

−3.8 (25.2) |

−4.7 (23.5) |

−9.4 (15.1) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 121.4 (4.78) |

88.2 (3.47) |

79.4 (3.13) |

73.6 (2.90) |

65.0 (2.56) |

58.2 (2.29) |

67.4 (2.65) |

68.3 (2.69) |

77.3 (3.04) |

114.9 (4.52) |

123.8 (4.87) |

123.9 (4.88) |

1,061.3 (41.78) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 16.4 | 12.7 | 12.5 | 11.7 | 10.4 | 8.6 | 9.8 | 10.3 | 11.0 | 15.7 | 16.3 | 15.8 | 151.2 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 60.5 | 81.7 | 118.4 | 184.6 | 214.6 | 211.2 | 198.2 | 194.8 | 157.5 | 109.7 | 74.5 | 59.2 | 1,664.9 |

| Source 1: Met Office[12] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: KNMI[13] | |||||||||||||

Demography and economy

Truro urban area, which includes parts of surrounding parishes, had a 2001 census population of 20,920.[14] By 2011 the population, including Threemilestone, was 23,040. Its status as the county's prime destination for retail and leisure and administration is unusual in that it is only its fourth most populous settlement.[14] Furthermore, population growth at 10.5 per cent between 1971 and 1998 was slow compared with other Cornish towns and Cornwall as a whole.

Major employers include the Royal Cornwall Hospital, Cornwall Council, and Truro College. There are about 22,000 jobs available in Truro, compared to only 9,500 economically active people living in the city. Commutes into Truro are a major factor in its traffic congestion. Average earnings are higher than in the rest of Cornwall.

Housing prices in Truro in the 2000s were 8 or more per cent higher than in the rest of Cornwall. Truro was named in 2006 as the top small city in the United Kingdom for rising house prices, at 262 per cent since 1996.[15] There is heavy demand for new housing and a call for inner-city properties to be converted into flats or houses to encourage city-centre living and reduce dependence on cars.

Culture

Attractions

Truro's dominant feature is the Gothic-revival Truro Cathedral, designed by architect John Loughborough Pearson, rising 249 ft (76 m) above the city at its highest spire.[16] It took from 1880 to 1910 to build, on the site of the old St Mary's Church, consecrated over 600 years earlier. Enthusiasts of Georgian architecture are well catered for in the city, with terraces and townhouses along Walsingham Place and Lemon Street often said to be "the finest examples of Georgian architecture west of the city of Bath".[17]

The main attraction for regional residents is a wide variety of shops. Truro has various chain stores, speciality shops and markets that reflect its history as a market town. The indoor Pannier Market is open all year with many stalls and small businesses. The city is also popular for catering and for night life, with many bars, clubs and restaurants. Truro houses the Hall for Cornwall, a performing arts and entertainment venue.

The Royal Cornwall Museum is the oldest and premier museum in Cornwall detailing Cornish history and culture. Its collections cover fields such as archaeology, art and geology. Among the exhibits is the so-called Arthur's inscribed stone. Its parks and open spaces include Victoria Gardens, Boscawen Park and Daubuz Moors.

Events

Lemon Quay is the year-round centre of most festivities in Truro.

In April, Truro prepares to partake in the Britain in Bloom competition, with floral displays and hanging baskets dotted around the city throughout the summer. A "continental market" comes to Truro in the holiday-making season, featuring food and craft stalls from France, Spain, Italy, Germany, Belgium, the Netherlands, Greece and elsewhere.

Cornwall Pride, a Pride event that celebrates diversity and the LGBT community, takes place on the last Saturday of August. The Truro City Carnival, held every September over a weekend, includes various arts and music performances, children's activities, a fireworks display, food and drinks fairs, a circus, and a parade. A half-marathon organised by Truro Running Club also occurs in September, running from the city centre into the country towards Kea, returning to finish at Lemon Quay.

Truro marks Christmas with a Winter Festival that includes a "City of Lights" paper lantern parade. Local schools, colleges, and community and youth groups join in.[18][19] Students at the local college in Truro create large lanterns, complementing the work of the core artists team. There are Christmas lights throughout the city centre, with a switch-on event, speciality products and craft fairs, late-night shopping evenings, various cathedral events and a firework display on New Year's Eve. Christmas trees are placed on the Piazza and outside the cathedral at High Cross.

Sports

Truro temporarily became home to the Cornish Pirates rugby union club for the 2005–2006 season, but the team moved again for the 2006–2007 season to share the ground of Camborne RFC.[20] In April 2018, the construction of a Stadium for Cornwall was under discussion with Cornwall Council, which had pledged £3 million in funding for the £14.3 million project.[21] It is planned for a site in Threemilestone.[22] The town has an amateur rugby union side, Truro RFC, founded in 1885. It belongs to Tribute Western Counties West and plays home games at St Clements Hill. It has hosted the CRFU Cornwall Cup several times.

Truro City F.C., a football team in the National League South, is the only Cornish club ever to reach this tier of the football pyramid. The club achieved national recognition by winning the FA Vase in 2007, beating A.F.C. Totton 3–1 in only the second ever final at the new Wembley Stadium, and becoming the first Cornish side ever to win that award. Its home ground is Treyew Road. Cornwall County Cricket Club plays some of its home fixtures at Boscawen Park, which is also the home ground of Truro Cricket Club. Truro Fencing Club[23] is one of Britain's flagships, having won numerous national championships, and had three fencers selected for Team GB at the London 2012 Olympics. Other sports amenities include a leisure centre, golf course and tennis courts.

Media

Truro is the centre of Cornwall's local media. The countywide weeklies, the Cornish Guardian and The West Briton, are based in the city, the latter serving the Truro area with its Truro and Mid-Cornwall edition. The city also houses the broadcasting studios of BBC Radio Cornwall, and those of the West district of ITV Westcountry, whose main studio is now in Bristol after a merger with ITV West. This closed the studio in Plymouth and the Westcountry Live programme was replaced by The West Country Tonight.

Customs

A mummers play text attributed until recently to Mylor, Cornwall (much quoted in early studies of folk plays, such as The Mummers Play by R. J. E. Tiddy – published posthumously in 1923 – and The English Folk-Play (1933) by E. K. Chambers), has now been shown, by genealogical and other research, to have originated in Truro around 1780.[24][25]

The widespread tradition of Nine Lessons and Carols originated in Truro in 1880, when its bishop at the time, Edward White Benson, formalised the evening singing of carols before Christmas Day.[26][27]

Administration

Truro City Council, a city/parish council, is based upstairs at the Municipal Buildings in Boscawen Street. It runs parks, gardens and planting, mayoral and civic events, support of its overseas twinning, and tourist information. It also considers planning issues and is involved in creating the Truro and Kenwyn Neighbourhood Plan in association with Cornwall Council. The city divides into four wards: Boscawen, Moresk, Tregolls and Trehaverne, with 24 councillors elected for four-year terms.[28] Cornwall Council (a unitary authority) has its base at Lys Kernow (formerly County Hall) west of the city centre. It administers planning, infrastructure, development and environmental issues.

The elected City Council forms Truro's lowest level of government,[29] as one of 213 parish bodies in the county. The governance layer above is the unitary Cornwall Council, directly under central government.[30][31] It covers Truro's public library, parks and gardens, tourist information centre, allotments and cemeteries.[32] It is affiliated to Truro Chamber of Commerce and other civic bodies.[33][34]

Truro's borough court was first granted in 1153; it became a free borough in 1589,[35] then a city in 1877, receiving letters patent after the Anglican diocese was located there in 1876.[36] However, it forms the eighth smallest in the UK in terms of population, city council area and urban area.[37]

Namesakes

Several towns outside Britain have taken Truro as their name:

|

|

Transport

Roads and bus services

Truro is 6 miles (9.7 km) from the A30 trunk road, to which it is linked by the A39 from Falmouth and Penryn. Also passing through is the A390 between Redruth to the west and Liskeard to the east, where it joins the A38 for Plymouth, Exeter and the M5 motorway. Truro as the most southerly city in the United Kingdom is just under 232 miles (373 km) west-south-west of Charing Cross, London.

The city and its surroundings have extensive bus services, mostly operated by First Kernow and Transport for Cornwall. Most terminate at Truro bus station near Lemon Quay. A permanent Park and Ride scheme, known as Park for Truro, which began operation in August 2008. Buses based at Langarth Park in Threemilestone carry commuters into the city via Truro College, the Royal Cornwall Hospital Treliske, County Hall, Truro railway station, the Royal Cornwall Museum and Victoria Square, and through to a second car park on the east side of Truro. Truro also has Longer-distance bus services run by National Express.

Railways

Truro railway station, about 1 km (0.6 mi) from the city centre, is on the Cornish Main Line with direct connections to London Paddington and to the Midlands, North and Scotland. North-east of the station is a 28-metre-high (92-foot) stone viaduct with views over the city, cathedral, and Truro River in the distance. The viaduct – the longest on the line – replaced Isambard Kingdom Brunel's wooden Carvedras Viaduct in 1904. Connecting to the main line at Truro station is the Maritime Line to Falmouth in the south.

Truro's first railway station was at Highertown. It was opened in 1852 by the West Cornwall Railway for trains to Redruth and Penzance, and was known as Truro Road Station. It was extended to the Truro River at Newham in 1855, but closed, so that Newham served as the terminus. When the Cornwall Railway connected the line to Plymouth, their trains ran to the present station above the city centre. The West Cornwall Railway (WCR) diverted most of its passenger trains to the new station, leaving Newham mainly as a goods station until it closed in 1971. The WCR became part of the Great Western Railway. The route from Highertown to Newham is now a cycle path, which takes a countryside loop through the south side of the city. The steam locomotive, the City of Truro, was built in 1903 and still runs on UK mainline and preserved railways.

Air and river transport

Newquay, Cornwall's main airport, is 12 mi (19 km) north of Truro. It was thought in 2017 to be the "fastest growing airport" in the UK.[39] It has regular flights to London Heathrow and other airports, and to the Isles of Scilly, Dublin and Düsseldorf, Germany.[40]

There is also a boat link to Falmouth along the Truro and Fal four times daily, tide permitting. The fleet run by Enterprise Boats as part of the Fal River Links calls on the way at Malpas, Trelissick, Tolverne and St Mawes.

Churches

The old parish church of Truro was St Mary's, which was incorporated into the cathedral in the later 19th century. The building dates from 1518, with a later tower and spire, dating from 1769. [8]

Parts of the town were in the parishes of Kenwyn and St Clement (Moresk) until the mid 19th century, when other parishes were created. St George's church in Truro, designed by the Reverend William Haslam, vicar of Baldhu, was built of Cornish granite in 1855; it is lofty and imposing. The parish of St George's Truro formed from part of Kenwyn in 1846. In 1865 two more parishes were created: St John's from part of Kenwyn and St Paul's from part of St Clement.[41][42] St George's contains a large wall painting behind the high altar which was the work of Stephany Cooper in the 1920s. Her father Canon Cooper had been a missionary in Zanzibar and elsewhere. The theme of the mural painting is "Three Heavens": the first heaven has views of Zanzibar and its cathedral (a happy period in the life of the artist); the second heaven has views of the city of Truro including the cathedral, the railway viaduct and St George's church (another happy period in the life of the artist); the third heaven is above the others which are separated from it by the River of Life (Christ is represented bridging the river and 17 saints including St Piran and St Kenwyn are depicted in this part).[43]

Charles William Hempel was organist of St. Mary's Church for forty years from 1804, supplementing his income by teaching music. In 1805 he composed and printed Psalms from the New Version for the use of the Congregation of St. Mary's, and in 1812 Sacred Melodies for the same congregation. These melodies became very popular.

The oldest church in Truro is at Kenwyn, on the northern side of the city. It dates from the 14th and 15th centuries, but it was almost entirely rebuilt in 1820, having deteriorated to the point where it had been deemed unsafe and had to be shut.[44]

St John's Church (dedicated to St John the Evangelist) was built in 1828 (architect P. Sambell) in the Classical style on a rectangular plan and with a gallery. Alterations were carried out in the 1890s.

St Paul's Church was built in 1848. The chancel was replaced in 1882–1884, the new chancel being the work of J. D. Sedding. The tower is "broad and strong" (Pevsner) and the exterior of the aisles are ornamented in Sedding's version of the Perpendicular style.[45] In the parish of St Paul is the former Convent of the Epiphany (Anglican) at Alverton House, Tregolls Road, an early 19th-century house. The house was extended for the convent of the Community of the Epiphany and the chapel was built in 1910 by Edmund H. Sedding.[45] The sisterhood was founded by the Bishop of Truro, George Howard Wilkinson, in 1883 and closed in 2001 when two surviving nuns moved into care homes. The sisters had been involved in pastoral and educational work and care of the cathedral and St Paul's Church.[46] St Paul's Church, built with a tower on a river bed with poor foundations, has fallen into disrepair and is no longer in use. Services are now held at the churches of St Clement, St George, and St John. St Paul and St Clement form a united benefice, as do St George and St John.

Only one Methodist chapel remains in use, in Union Place (Truro Methodist Church), which has a broad granite front (1830, but since enlarged). There is a Quaker Meeting House in granite (c. 1830) and numerous other churches, some meeting in their own modern buildings, e. g. St Piran's Roman Catholic church and All Saints, Highertown, and some in schools or halls. St Piran's, dedicated to Our Lady of the Portal and St Piran, was built on the site of a medieval chapel by Margaret Steuart Pollard in 1973, for which she received the Benemerenti Medal from the Pope.[47] The Baptist church building occupies the site of the former Lake's pottery, one of the oldest in Cornwall.

Education

A free grammar school associated with St Mary's Church was endowed in the 16th century. Its distinguished pupils have included the scientist Sir Humphry Davy, General Sir Hussey Vivian and the clergyman, Henry Martyn.[8]

The former Truro Girls Grammar School was converted into a Sainsbury's supermarket.[48]

Educational institutions in Truro today include:

- Archbishop Benson – A Church of England voluntary aided primary school

- Polwhele House Preparatory School — since the closure of Truro Cathedral School educating also the 18 boy choristers of Truro Cathedral

- Truro School — a public school founded in 1880

- Truro High School for Girls — a public school for ages 13–18

- Penair School — a state co-educational science college for ages 11–16

- Richard Lander School — a state co-educational technology college for ages 11–16

- Truro College — A further and higher education college attached to the Combined Universities in Cornwall

- University of Exeter Medical School[49]

Development

Truro has many proposed development schemes and plans, the majority of which are intended to counter the main problems it faces, notably traffic congestion and lack of housing.

Major proposals include the construction of a distributor road to carry traffic away from the busy Threemilestone-Treliske-Highertown corridor, reconnecting at either Green Lane or Morlaix Avenue. This will also serve the new housing planned for that area.[50]

Changes are proposed for the city centre, such as pedestrianisation of the main shopping streets and beautification of a list of uncharacteristic storefronts built in the 1960s.[50] New retail developments on the current Carrick District Council site and Garras Wharf waterfront site will provide more space for shops, open spaces and public amenities.[50] Along with the redevelopment of the waterfront, a tidal barrier is planned to dam water into the Truro River, which is currently blighted by mud banks that appear at low tide.[50]

Controversial plans include the construction of a new stadium for Truro City F.C. and the Cornish Pirates, and relocation of the city's golf course to make way for more housing. A smaller project is the addition of two large sculptures in the Piazza.[51]

Notable residents

_RMG_BHC2565.tiff.jpg.webp)

Public thinking, public service

- Sir Henry Killigrew (c. 1528–1603), Cornish diplomat and an ambassador[52]

- Owen Fitzpen (1552–1636), philanthropist and merchant seaman, led a successful slave revolt in 1627 to free captives of Barbary pirates, memorialised on a plaque in St Mary's Church.

- John Robartes, 1st Earl of Radnor (1606–1685) a politician who fought for the Parliamentary cause[53]

- William Gwavas (1676–1741), barrister and writer in the Cornish language[54]

- Edward Boscawen (1711–1761), Royal Navy admiral, eponym of a cobbled street at the centre of Truro and a park [55][56]

- Samuel Walker (1714–1761), evangelical clergyman, curate of Truro from 1746

- Richard Polwhele (1760–1838) a clergyman, poet and historian of Cornwall and Devon[57]

- Charles Sandoe Gilbert (1760–1831), druggist and historian of Cornwall[58]

- Hussey Vivian, 1st Baron Vivian (1775–1842) a senior British cavalry officer[59]

- Henry Martyn (1781–1812), Cambridge mathematician and missionary in India and Persia, who translated the Bible into local languages[60]

- Admiral Sir Barrington Reynolds GCB (1786–1861) senior Royal Navy officer[61]

- Richard Spurr (1800–1855), cabinet maker and lay preacher imprisoned for Chartism. A large allotment in the town was dedicated to him in 2011.

- Major-General Sir Henry James (1803–1877), a Royal Engineers officer and DG of the Ordnance Survey 1854–1875[62]

- Richard Lemon Lander (1804–1834), explorer in West Africa.[63] A local secondary school is named in his honour and a monument to his memory stands at the top of Lemon Street.

- John Lander FRGS (1806–1839), printer and explorer with his brother Richard Lemon Lander[64]

- Charles Chorley (c. 1810–1874), journalist and man of letters[65]

- William Bennett Bond (1815–1906), Canadian priest and second primate of the Anglican Church of Canada

- Alexander Mackennal (1835–1904), nonconformist minister[66][67]

- Silvanus Trevail (1851–1903) local architect and mayor of Truro[68]

- Joseph Hunkin (1887–1950), Bishop of Truro from 1935 to 1950[69]

- James Henry Fynn (Finn, 1893–1917), recipient of the Victoria Cross

- Barbara Joyce West (1911–2007), second-to-last survivor of the RMS Titanic

- Alison Adburgham (1912–1997), social historian and fashion journalist, died in the town.[70]

- Hugh Clegg (1920–1995), academic, founded the National Board for Prices and Incomes (1965–1971)

- David Penhaligon (1944–1986), politician, Liberal MP for Truro 1974–1986[71]

- Paul Myners, Baron Myners, CBE (born 1948), businessman and politician

- Mark Laity (born c. 1962), NATO spokesman and former BBC correspondent

- NneNne Iwuji-Eme (born c. 1978), British diplomat, UK High Commissioner to Mozambique

- Staff Sergeant Olaf Schmid, GC (1979–2009), a British Army bomb-disposal expert

Arts

- Giles Farnaby (c. 1563–1640), composer and virginalist[72]

- Samuel Foote (1720–1777), actor and playwright[73]

- Henry Bone (1755–1834), porcelain, jewellery and enamel painter[74]

- Joseph Antonio Emidy (1775–1835), former slave from Guinea turned violinist

- Charles William Hempel (1777–1855), organist of St Mary's Church, Truro, and poet[75]

- Nicholas Michell (1807–1880) a Cornish writer, best known for his poetry[76]

- Charles Frederick Hempel (1811–1867), organist and composer[77]

- Walter Hawken Tregellas (1831–1894) professional draughtsman and historical and biographical writer[78]

- Francis Charles Hingeston-Randolph (1833–1910), cleric, antiquary and author[79]

- Henry Dawson Lowry (1869–1906), journalist, short story writer, novelist and poet[80]

- Hugh Walpole (1884–1941) novelist, who attended a preparatory school in Truro

- Maria Kuncewiczowa (1895–1989), Polish writer living in Truro after WWII. Her novel Tristan 1946 was set here.

- Margaret Steuart Pollard (1904–1996), poet and translator lived in Truro from 1930s

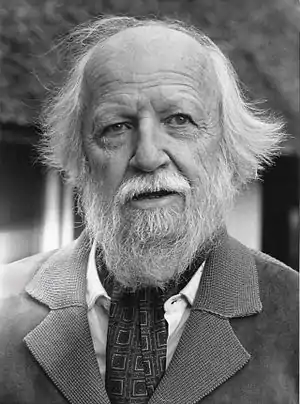

- William Golding (1911–1993), novelist, playwright and poet, gained the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1983. Born in St Columb Minor, he returned to live near Truro in 1985.

- Alison Adburgham (1912–1997), author, social historian and fashion editor of The Guardian

- Irene Newton (1915–1992), artist[81]

- Catherine Grubb, artist (born 1945), lives in Truro.[82]

- Roger Taylor (born 1949), drummer from the rock band Queen[83]

- Robert Goddard (born 1954), novelist, lives in Truro.

- James Marsh (born 1963), film director and Academy Award winner[84]

- Ben Salfield (born 1971), guitarist, lutenist, composer and teacher, has lived in Truro since age of nine.

- Paul Kerensa (born 1979), comedy writer and stand-up comedian[85]

- Brett Harvey (born c. 1980), film writer and director based in Cornwall[86]

- Calvin Dean (born 1985), award-winning actor[87]

Science and business

- John Vivian (1750–1826) industrialist in Swansea, descendant of the Vivian family

- Elizabeth Andrew Warren (1786–1864) a Cornish botanist and marine algologist

- Charles Foster Barham (1804–1884), physician and writer on public health[88]

- Edwin Dunkin FRS (1821–1898) an astronomer and the president of the Royal Astronomical Society

- Henry Charlton Bastian (1837–1915), physiologist and neurologist

- Edward Arnold (1857–1942), a publisher, founded Edward Arnold Publishers Ltd in 1890.

- Elsie Wilkins Sexton (1868–1959) a zoologist and biological illustrator

- H. Lou Gibson (1906–1992), expert in medical uses of infrared to detect breast cancer

Sport

- Nick Nieland (born 1972), javelin gold medallist at the 2006 Commonwealth Games

- Matthew Etherington (born 1981), former professional footballer with 426 club caps, he played for West Ham and Stoke City.

- David Paynter (born 1981), former first-class cricketer

- Tom Voyce (born 1981) former rugby union footballer with London Wasps and England

- Annabel Vernon (born 1982), retired rower, team silver medallist at the 2008 Summer Olympics

- Chris Harris (born 1982), international speedway rider

- Gemma Prescott (born 1983), Paralympic track and field athlete

- Darren Dawidiuk (born 1987), rugby union footballer

- Craig Alcock (born 1987), professional footballer with 300 club caps

- Matthew Whorwood (born 1989), Paralympic swimmer, bronze medallist in two Paralympic Games

- Matthew Shepherd (born 1990), rugby union player

References

- Office for National Statistics Archived 8 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine 2011 census – Truro CP

- "List of Place-names agreed by the MAGA Signage Panel" (PDF). Cornish Language Partnership. May 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 11 January 2015.

- "17 reasons to be proud to be a Truronian on Truro Day". cornwalllive.com. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- O. J. Padel (1988) A Popular Dictionary of Cornish Place-names, Penzance: A. Hodge ISBN 0-906720-15-X.

- Parochial history of Cornwall, Davis Gilbert.

- patronymica Cornu-Britannica.

- De Lucy in the 12th century, Norman Lucey 2009 [lucey.net/webpage62.htm].

- "Trudox-Hill – Trysull Pages 395–398 A Topographical Dictionary of England. Originally published by S Lewis, London, 1848". British History Online.

- Pascoe, W. H. (1979). A Cornish Armory. Padstow, Cornwall: Lodenek Press. p. 135. ISBN 0-902899-76-7.

- "History of Truro". Truro Town Site. Archived from the original on 10 April 2008. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

- "Wanted, recruits for the Duke of Cornwall's Light Infantry. Young Men apply to J. G. Myners, New Bridge-street, Truro". Royal Cornwall Gazette. 14 August 1890. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- "Camborne 1981–2010 averages". Met Office. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- "Camborne extremes". KNMI. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- "Census 2001 Key Statistics for urban areas in England and Wales" (PDF). National Office of Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 May 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

- "Homes in smaller cities cost more". BBC News. 20 May 2006. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

- "Building Statistics – Truro Cathedral, Truro". Emporis. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

- "Daytripper – Sheer Indulgence in Truro". Truro City Council. Archived from the original on 7 October 2007. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

- "Schools and Groups – Truro City of Lights". cityoflights.org.uk. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- "Truro City of Lights parade 2010". 4 November 2010 – via news.bbc.co.uk.

- "Pirates want to stay at Camborne". 17 November 2008. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- Rees, Paul (17 April 2018). "Stadium for Cornwall moves step closer with £3m of council funding". The Guardian.

- "Renewed hope for sports stadium". BBC News. 21 December 2007. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

- "Truro Fencing Club". Truro Fencing Club. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- "FindArticles.com – CBSi". Archived from the original on 30 August 2004. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- "Truro [Formerly Mylor]: "A Play for Christmas", 1780s". folkplay.info. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- Archive, The British Newspaper. "Register | British Newspaper Archive". www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- "BBC – Cornwall – Faith – Festival of Nine Lessons and Carols". bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- "Councillors & Wards". Truro City Council. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

- "Home – Truro City Council". Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Committee, Great Britain: Parliament: House of Commons: ODPM: Housing, Planning, Local Government and the Regions (2006). Is There a Future for Regional Government?: Session 2005–06. The Stationery Office. ISBN 9780215027849.

- Council, Cornwall. "Council and democracy – Cornwall Council". Government of the United Kingdom. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Truro, Totally. "Work and business: Truro City Council | enjoy truro". www.enjoytruro.co.uk. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Association, Come to Cornwall (1960). City of Truro, Cornwall: Official Guide, Issued in Support of the "Come to Cornwall" Movement Under the Authority of the Truro City Council and the Truro Chamber of Commerce.

- Journal of the Institution of Municipal Engineers. NaN. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - "Crime and Punishment – Truro Uncovered". trurouncovered.co.uk.

- Beckett, John (2017). City Status in the British Isles, 1830–2002. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781351951265. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- "Truro Cathedral". Cornwall Guide. 6 December 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- "Aims of Twinning". Truro-Morlaix Twinning Association. Retrieved 10 May 2010.

- "Newquay is officially the UK's fastest growing airport". The Independent. Retrieved 3 October 2018.

- Destinations. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- Cornish Church Guide (1925) Truro: Blackford; pp. 210–211.

- "Parishes of St Paul, Truro, St Clement, St George, Truro, and St John, Truro (united benefice)". Truro Churches (official). Retrieved 15 December 2009.

- Joan Rendell (1982) Cornish Churches. St Teath: Bossiney Books; pp. 38–39.

- History of the church. Retrieved 16 July 2020.

- Pevsner, N. (1970) Cornwall; 2nd ed. Penguin Books; pp. 234–235.

- Cornish Church Guide. Truro: Blackford; pp. 325–326.

- Polly Bagnall & Sally Beck (2015). Ferguson's Gang: The Remarkable Story of the National Trust Gangsters. Pavilion Books. p. 10. ISBN 978-1909881716.

- "Grammar 'girls' share memories of schooldays". West Briton.

- "University of Exeter". Archived from the original on 3 April 2020. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- "Truro and Threemilestone Action Plan". Carrick District Council. Archived from the original on 20 December 2008. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

- "The Lemon Quay Sculptures". Truro City Council. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 13 January 2008.

- . Dictionary of National Biography. 31. 1892.

- . Dictionary of National Biography. 48. 1896.

- . Dictionary of National Biography. 23. 1890.

- . Dictionary of National Biography. 05. 1886.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 04 (11th ed.). 1911.

- . Dictionary of National Biography. 46. 1896.

- . Dictionary of National Biography. 21. 1890.

- . Dictionary of National Biography. 58. 1899.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). 1911.

- . Dictionary of National Biography. 48. 1896.

- . Dictionary of National Biography. 29. 1892.

- . Dictionary of National Biography. 32. 1892.

- . Dictionary of National Biography. 32. 1892.

- . Dictionary of National Biography. 10. 1887.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 17 (11th ed.). 1911.

- . Dictionary of National Biography (2nd supplement). 1912.

- Shepherd, Matt (5 January 2015). "Silvanus Trevail". BBC. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- "Joseph Hunkin in New York". 14 February 1938. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- "Adburgham, Alison". guardian.calmview.eu. Guardian Observer archive. Archived from the original on 31 December 2017. Retrieved 2 August 2015.

- HANSARD 1803–2005 → Mr David Penhaligon. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- . Dictionary of National Biography. 18. 1889.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 10 (11th ed.). 1911.

- . Dictionary of National Biography. 05. 1886.

- . Dictionary of National Biography. 25. 1891.

- . Dictionary of National Biography. 37. 1894.

- . Dictionary of National Biography. 25. 1891.

- . Dictionary of National Biography. 57. 1899.

- . Dictionary of National Biography (2nd supplement). 1912.

- . Dictionary of National Biography (2nd supplement). 1912.

- Sara Gray (2019). British Women Artists. A Biographical Dictionary of 1000 Women Artists in the British Decorative Arts. Dark River. ISBN 978 1 911121 63 3.

- "Catherine GRUBB". Cornwall Artists. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- IMDb Database. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- IMDb Database retrieved 21 January 2020.

- IMDb Database. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- IMDb Database. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- IMDb Database. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- . Dictionary of National Biography. 03. 1885.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Truro. |

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. 27 (11th ed.). 1911.

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Truro (England). |

- Truro at Curlie

- Truro City Council website

- Cornwall Record Office Online Catalogue for Truro

- Truro – historic characterisation for regeneration (CSUS)

- Enjoy Truro – official guide to the city, including latest news and events (provided by Totally Truro, the local not-for-profit Business Improvement District)