Japanese Buddhist pantheon

The Japanese Buddhist Pantheon designates the multitude (the Pantheon) of various Buddhas, Bodhisattvas and lesser deities and eminent religious masters in Buddhism. A Buddhist Pantheon exists to a certain extent in Mahāyāna, but is especially characteristic of Vajrayana Esoteric Buddhism, including Tibetan Buddhism and especially Japanese Shingon Buddhism, which formalized it to a great extent. In the ancient Japanese Buddhist Pantheon, more than 3,000 Buddhas or deities have been counted, although nowadays most temples focus on one Buddha and a few Bodhisattvas.[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism in Japan |

|---|

|

History

Early, pre-sectarian Buddhism had a somewhat vague position on the existence and effect of deities. Indeed, Buddhism is often considered atheistic on account of its denial of a creator god and human responsibility to it. However, nearly all modern Buddhist schools accept the existence of gods of some kind; the main point of divergence is on the influence of these gods. Of the major schools, Theravada tends to de-emphasize the gods, whereas Mahayana and Vajrayana do not.

The rich Buddhist Pantheon of northern Buddhism ultimately derives from Vajrayana and Tantrism.[2] The historical devotional roots of pantheistic Buddhism seem to go back to the period of the Kushan Empire.[3] The first proper mention of a Buddhist Pantheon appears in the 3-4th century Guhyasamāja, in which five Buddhas are mentioned, the emanations of which constitute a family:[3][4]

The five Kulas are Dvesa, Moha, Rāga, Cintāmani, and Samaya, which conduce to the attainment of all desires and emancipation

— Guhyasamāja.[4]

By the 9th century under the Pala king Dharmapala, the Buddhist Pantheon had already swelled to about 1,000 Buddhas.[5] In Japan, Kūkai introduced Shingon Esoteric Buddhism and its Buddhist Pantheon, also in the 9th century.[6]

Hierarchical structure of the Buddhist pantheon

The Buddhist Pantheon in Japanese Buddhism is defined by a hierarchy in which the Buddhas occupy the topmost category, followed in order by the numerous Bodhisattvas, the Wisdom Kings, the Deities, the "Circumstantial appearances" and lastly the patriarchs and eminent religious people.[7]

| Level | Category | Japanese nomenclature |

|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | Buddhas | Nyorai-bu (如来部) |

| Level 2 | Bodhisattvas | Bosatsu-bu (菩薩部) |

| Level 3 | Wisdom Kings | Myōō-bu (明王部) |

| Level 4 | Heavenly deities | Ten-bu (天部) |

| Level 5 | Circumstantial appearances | Gongen (権現) |

| Level 6 | Religious masters | Kōsō - Soshi (高僧・祖師) |

A famous statue group, the mandala located at Tō-ji temple in Kyōto, shows some of the main elements and structure of the Buddhist Pantheon. The mandala was made in the 9th century and offered to Kūkai.[8] A duplicate was brought to Paris, France, by Emile Guimet at the end of the 19th century, and is now located in the Musée Guimet.[8]

Japanese Buddhism incorporated numerous Shintō deities in its pantheon and reciprocally. Japanese Shingon also has other categories, such as the Thirteen Buddhas.[9] Zen Buddhism however clearly rejected the strong polytheistic conceptions of orthodox Buddhism.[10]

Level 1: Buddhas (Nyorai-bu)

A Buddha is one who has attained enlightenment and reached the state of nirvana. Buddhas are distinct from Bodhisattvas because they have chosen to leave earth.

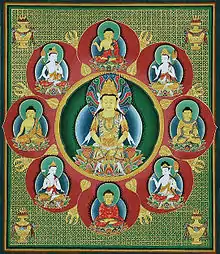

Five Wisdom Buddha

The five Wisdom Buddhas (五仏) are centered around Vairocana (Japanese: Dainichi Nyorai, 大日如来), the supreme Buddha. Each of the four remaining Buddhas occupies a fixed cardinal point. Each of them is a manifestation of Buddhahood, and each is active in a different world-period, in which they manifest themselves among Bodhisattvas and humans.[11] An enlightened being is one who embodies the qualities of the five Buddha Families, or the five Wisdom Buddhas, and in doing so has shed the negative emotions which cause pain and suffering throughout life.[12] These five key emotions are known as “disturbing” emotions and they include: attachment, anger, ignorance, pride, and envy.[12] When these emotions are exercised they cause ourselves and others around us harm and suffering and can potentially cause a lower level reincarnation in the next life. Therefore, by eliminating these emotions allow one to attain enlightenment by recognizing and becoming one with the five Wisdom Buddha.[12]

| Fukūjōju Nyorai

(north) |

||

| Amida Nyorai

(west) |

Dainichi Nyorai (principal deity) |

Ashuku Nyorai

(east) |

| Hōshō Nyorai

(south) |

These "Dhyani Buddhas" form the core of the Buddhist pantheistic system, which developed from them in a multiform way.[3] At the Musée Guimet, the five Buddhas are surrounded by protective Bodhisattvas.[8] The five Wisdom Buddhas are known as, Akshobhya, Ratnasambhava, Amitabha, Amogasiddha, and Vairocana. They each have varying characteristics and attributes specific to their purpose. The first Buddha, Akshobhya, is colored blue and sits in a vajra posture with his hand touching the ground.[12] The color blue and the vajra posture symbolize changelessness and permanance which is particular to him because he focuses on easing emotions that spur from anger.[12] His wisdom is known as the “mirror-like” wisdom because when one is freed from anger and the feelings accompanied with anger, one is able to have an unbiased awareness of our daily experiences.[12] "Mirror-like" wisdom is the idea that one can see things for how they really are instead of having a blurred perspective that is caused from one's anger getting in the way of seeing the truth. The second Buddha, Ratnasambhava, is concerned with the enrichment of oneself.[12] When one has been cleansed of the disturbing emotion of pride, one's ego becomes objective and this enables fairness and equality in regards to all aspects of one's life. This Buddha is a yellowish, gold color and he holds a wish-fulfilling jewel in his hand. The golden color is meant to symbolize wealth in a fulfilled sense and the wish-fulfilling jewel symbolizes his activity of enrichment because it is able to grant any desirable wish.[12] This Buddha sits in vajra posture which represents fulfillment and suggests supreme generosity by giving the mudra hand gesture.[12] The third Buddha, Amitabha, is focused on the elimination of the strong feeling of desire.[12] Desire is one of the five disturbing emotions that causes one to have neverending wants and ultimately cultivates suffering. If one cannot attain his desires then he will feel unfulfilled and empty.[12] The loss of great desire allows one to rise above to a more simplistic way of life with overwhelming gratitude. With recognition of this Buddha one will be able to find appreciation in the small things and see things for their true worth with an unbiased perspective.[12] Buddha Amitabha is from the lotus family and is seated in vajra posture with his hands placed in the meditative posture for mental clarity.[12] The fourth Buddha, Amogasiddha, is focused on the strength of wisdom and the elimination of jealousy.[12] Jealousy is a hindrance in which infringes on and distracts from ones wisdomly abilities. Buddha Amogasiddha’s activity is “meaningful accomplishment” which spurs from undistracted and engaged wisdom.[12] With great wisdom, one is able to observe and overcome trivial uprisings in an intelligent and calm manner. His right hand is gesturing "fearless protection" from things that may hinder one's wisdom.[12] The fifth Buddha, Vairocana, is focused on the elimination of ignorance from one's mental state.[12] Ignorance makes one’s perspective unclear and causes one to make judgements from a subjective view. Buddha Vairocana holds the wheel of dharma, the symbol of buddhist law, in his hands.[12] The gesture of the wheel of dharma serves the purpose of symbolizing uninterrupted knowledge of how the world works.[12] The wheel represents knowledge of the Buddhas teachings which lead one to enlightenment.[12]

There is also a multitude of other Buddhas, such as Yakushi, the Buddha of medicine. Buddha Yakushi was widely worshipped during the Heian Period in Japan.[13] Yakushi was known as the Medicine Buddha and people would pray to him for protection against vengeful spirits and natural disaster.[13] Yakushi can be recognized in Buddhist art by the iconography of the medicine jar which he holds in his hand.

Level 2: Bodhisattvas (Bosatsu-bu)

A bodhisattva is one who has attained enlightenment and has chosen to stay on earth and spread his knowledge of enlightenment to others so that they too can gain enlightenment.[14] Bodhisattvas are paragons of compassion in Mahayana Buddhism. In the Buddhist Pantheon, besides the past and future Buddhas, there are numerous Bodhisattvas as well.[15]

Sometimes, five main "Matrix" Bodhisattvas are determined (五大菩薩), grouped around a central Bodhisattva, Kongō-Haramitsu (金剛波羅蜜菩薩) in the case of Tōji Temple.[8]

| Miroku

(north) |

||

| Kannon

(west) |

Kongō-Haramitsu (principal deity) |

Fugen

(east) |

| Monju

(south) |

Beyond these five main Bodhisattvas, there exists a huge number of other Bodhisattvas, all beings who have postponed enlightenment for the benefit of helping mankind.

Kongōhō Bosatsu/ Vajraratsa.

Kongōhō Bosatsu/ Vajraratsa.

Jizō.

Jizō.

Level 3: Wisdom Kings (Myōō-bu)

The Wisdom Kings (Vidyârâjas) were initially divinities of Esoteric Buddhism but were then later adopted by Japanese Buddhism as a whole. These Gods are equipped with superior knowledge and power that give them influence on internal and external reality. These Kings became the object of personification, either peaceful in the case of female personifications, and wrathful in the case of male personifications. Their aggressivity expresses their will to get rid of negative forces in devotees and in the world. They are therefore an expression of the Buddha's compassion for all beings.[8]

Five Wisdom Kings

The Five Wisdom Kings (五大明王) are emanations of the Buddhas and protect them. They are usually represented as violent beings. They represent the ambivalent in nature, and seem to derive from ancient Yaksa and Brahmanical tradition.[16]

| Kongō-Yasha

(north) |

||

| Daiitoku

(west) |

Fudō-Myō (principal deity) |

Gosanze

(east) |

| Gundari

(south) |

Beyond the five principal kings, numerous other Wisdom Kings exist with a great variety of roles.

Other Wisdom Kings

Many more Wisdom Kings also exist with numerous functions. In general, the Wisdom Kings are viewed as the guardians of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas.

Level 4: Heavenly deities (Ten-bu)

Gods, although benefiting from an exceptional longevity, nevertheless are submitted to the cycle of rebirths, and remain outside of the world of enlightenment and Nirvana. They are aiming to reach Nirvana eventually, however, and therefore endeavour to help Buddhism and its devotees.[8] According to Buddhist cosmology, adopted from Indian cosmology, the deities live in the Three Worlds and are positioned hierarchically according to their position in respect to the cosmic axis of Mount Sumeru. High above the mountain resides Brahma, on the summit reside the Thirty Three Gods with Indra as their king, at half-height reside the God Kings of the Orient, and at the bottom inferior deities.[8] Numerous deities are included in the Buddhist pantheon.

The term Ten (天) is the equivalent of the Indian Deva and designated the higher divinities from the Four Heavenly Kings up. The term Jin (神) designated lower-level deities.[8]

The Four Heavenly Kings are an important part of these deities.

The Heavenly King Zōchō.

The Heavenly King Zōchō. Bonten (梵天)/ Brahma.

Bonten (梵天)/ Brahma.

Marishi-Ten (摩利支天)/ Marici.

Marishi-Ten (摩利支天)/ Marici. Ugajin (宇賀神), masculine form.

Ugajin (宇賀神), masculine form. Ugajin (宇賀神), feminine form.

Ugajin (宇賀神), feminine form.

Incomplete list of Mikkyō devas originated from Hindu deities:

- Kangiten (歓喜天) / Ganesha

- Taishakuten (帝釈天) / Indra

- Benzaiten (弁財天) / Saraswati

- Kisshōten (吉祥天) / Lakshmi

- Bichūten (毘紐天) / Vishnu

- Daikokuten (大黒天) / Mahakala

- Daijizaiten (大自在天) / Mahesvara

- Umahi (烏摩妃) / Uma

- Katen (火天) / Agni

- Jiten (地天) / Prthivi

- Nitten (日天) / Surya

- Gatten (月天) / Chandra

- Suiten (水天) / Varuna

- Fūten (風天) / Vayu

- Kumaraten (鳩摩羅天) / Kumara

- Naraenten (那羅延天) / Narayana

- Rago (羅睺) / Rahu

- Izanaten (伊舎那天) / Ishana

- Enma (閻魔) / Yama

Level 5: Circumstantial appearances (Suijakushin)

Although divinities are considered to be subjects to the law of impermanence, Buddhism nevertheless considers that men should place themselves under their protection. When Buddhism entered Japan in the 6th century numerous Shintō divinities (kami) were also present in the Japanese islands, although they had no iconography. The shuijakushin category is specific to Japan and provides for the incorporation into Buddhism of these Shintō kami.

The Buddhist term "Gongen" 権現 or "Avatar" (meaning the capability of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas to change their appearance to that of a Japanese kami to facilitate conversion of the Japanese) thus came into use in relation to these gods. Shintō deities came to be considered as local appearances in disguise of foreign Buddhas and Bodhisattvas (suijakushin (垂迹神, circumstantial appearance gods)).[17] Thus numerous Shinto figures have been absorbed as Buddhist deities.[9] This was also sometimes reciprocal, as in the case of Buddhist Benzaiten and Shinto kami Ugajin.

This syncretism was officially abolished by the establishment of the Meiji Emperor in 1868 with the Shinto and Buddhism Separation Order (神仏分離令, also 神仏混淆禁止 Shinbutsu Konkō Kinshi).[8]

The Six Kannon are a group of deity sculptures that were originally placed together in the temple at Daihoonji.[18] The sculptures were made by the sculptor Jōkei in 1224.[18] The idea of grouping statues together is popular in Buddhism because it is said that it increases the power of the deities when they are shown as a group.[18] However, it is popular for the Six Kannon to be enshrined at temples throughout Japan individually as well.[18] The group of six consists of Shō Kannon, Thousand-armed Kannon, Horse-headed Kannon, Eleven-headed Kannon, Juntei Kannon, and Nyoirin Kannon.[18] These Six Kannon although alike, have distinct attributes which set them apart from one another.

Circumstantial appearances of Mount Atago (愛宕権現), in the shape of General Jizō.

Circumstantial appearances of Mount Atago (愛宕権現), in the shape of General Jizō. Kompira Daigongen (金毘羅大権現), divinity of the Inland Sea and ships.

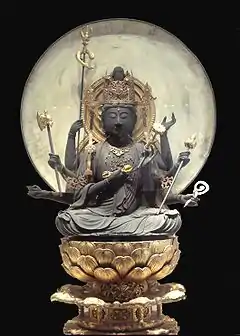

Kompira Daigongen (金毘羅大権現), divinity of the Inland Sea and ships. Sambō Kōjin (三宝荒神), the Fire Divinity. Uses the power of fire for the Buddhist cause.

Sambō Kōjin (三宝荒神), the Fire Divinity. Uses the power of fire for the Buddhist cause. Zaō Gongen (蔵王権現), circumstantial appearance of Mount Yoshino.

Zaō Gongen (蔵王権現), circumstantial appearance of Mount Yoshino.

Level 6: Religious masters (Kōsō・Soshi)

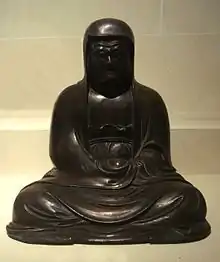

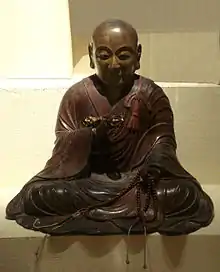

Buddhism has also created an iconography for the saint men who assisted to its diffusion. These are historical beings, although some legendary elements can be attached to them. Some, such as Kōbō-Daishi, the founder of Shingon Buddhism, are the subject of a devotion equivalent to that of the Buddhas or Bodhisattvas. Some have also acquired the qualities of protective spirits, such as Battabara protector of the baths, or Fudaishi, protector of monastical libraries. The list of these religious masters consists of men from the "Three Countries" where Buddhism was born and then prospered along the Silk Road: India, China, Japan.[8] The Sixteen Arhats, saint men who were predecessors or disciples of the Buddha, are also part of this category.

Master Kōbō Daishi founder of Shingon Buddhism.

Master Kōbō Daishi founder of Shingon Buddhism. Ingada sonja, one of the Sixteen Arhats.

Ingada sonja, one of the Sixteen Arhats. Battabara sonja, 跋陀婆羅尊者, protector of the baths.

Battabara sonja, 跋陀婆羅尊者, protector of the baths.

Nichiren Shōnin, 日蓮聖人, founder of the Nichiren Buddhism.

Nichiren Shōnin, 日蓮聖人, founder of the Nichiren Buddhism.

Eight Legions (Japanese: 八部衆, Hachi Bushū)

In Sanskrit, these classes of beings are called the Aṣṭagatyaḥ or the Aṣṭauparṣadaḥ.

See also

Notes

- Religion of the Samurai Kaiten Nukariya p.87

- An Introduction to Buddhist Esoterism Benoytosh Bhattacharyya p.120

- Buddhist art & antiquities of Himachal Pradesh, up to 8th century A.D. Omacanda Hāṇḍā p.82

- An Introduction to Buddhist Esoterism Benoytosh Bhattacharyya p.121

- Buddhist art & antiquities of Himachal Pradesh, up to 8th century A.D. Omacanda Hāṇḍā p.83

- The body: toward an Eastern mind-body theory Yasuo Yuasa, Thomas P. Kasulis p.125

- Notice at Musée Guimet

- Musée Guimet exhibit

- Sources of Japanese tradition William Theodore De Bary, p.338

- Religion of the Samurai Kaiten Nukariya p.88

- Religion in Nepal by K. R. van Kooij p.22

- Thrangu, Rinpoche (2001). The five Buddha families & the eight consciousnesses. Zhyisil Chokyi GhatsalPublications. ISBN 1877294144. OCLC 155719092.

- Suzuki, Yui (2012), "2: The Magical Yakushi: Spirit Pacifier and Healer-God", Medicine Master Buddha: The Iconic Worship of Yakushi in Heian Japan, Brill, pp. 29–44, doi:10.1163/9789004229174_004, ISBN 9789004229174

- Morse, A. N.; Morse, S. C. (1995). "Object as Insight: Japanese Buddhist Art and Ritual". Katonah Museum of Art.

- The Hero with a Thousand Faces Joseph Campbell p.129

- Tantric Buddhism and altered states of consciousness Louise Child p.109

- Ishii, Ayako, ed. (2008). Butsuzō no Mikata Handobukku (in Japanese). Tokyo: Ikeda Shoten. p. 120. ISBN 978-4-262-15695-8.

- Fowler, Sherry D. (2016-11-30), "Painting the Six Kannon", Accounts and Images of Six Kannon in Japan, University of Hawai'i Press, doi:10.21313/hawaii/9780824856229.003.0006, ISBN 9780824856229

- http://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/hachi-bushu.shtml#karura