Japanese diaspora

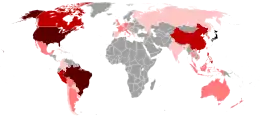

The Japanese diaspora, and its individual members known as nikkei (日系) or as nikkeijin (日系人), comprise the Japanese emigrants from Japan (and their descendants) residing in a country outside Japan. Emigration from Japan was recorded as early as the 15th century to the Philippines,[41][42][43] but did not become a mass phenomenon until the Meiji period (1868-1912), when Japanese emigrated to the Philippines[44] and to the Americas.[45][46] There was significant emigration to the territories of the Empire of Japan during the period of Japanese colonial expansion (1875-1945); however, most of these emigrants repatriated to Japan after the 1945 surrender of Japan ended World War II in Asia.[47]

According to the Association of Nikkei and Japanese Abroad, about 3.8 million nikkei live in their adopted countries. The largest of these foreign communities are in Brazil, the United States, the Philippines,[48] China, Canada, and Peru. Descendants of emigrants from the Meiji period still maintain recognizable communities in those countries, forming separate ethnic groups from Japanese people in Japan.[49] Nevertheless, most emigrant Japanese are largely assimilated outside of Japan.

As of 2018 the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs reported the 5 countries with the highest number of Japanese expatriates as the United States (426,206), China (124,162), Australia (97,223), Thailand (72,754) and Canada (70,025).[50]

Terminology

Nikkei is derived from the term nikkeijin (日系人) in Japanese,[51][52] used to refer to Japanese people who emigrated from Japan and their descendants.[52][53] Emigration refers to permanent settlers, excluding transient Japanese abroad. These groups were historically differentiated by the terms issei (first-generation nikkeijin), nisei (second-generation nikkeijin), sansei (third-generation nikkeijin), and yonsei (fourth-generation nikkeijin). The term Nikkeijin may or may not apply to those Japanese who still hold Japanese citizenship. Usages of the term may depend on perspective. For example, the Japanese government defines them according to (foreign) citizenship and the ability to provide proof of Japanese lineage up to the third generation—legally the fourth generation has no legal standing in Japan that is any different from another "foreigner." On the other hand, in the US or other places where Nikkeijin have developed their own communities and identities, first-generation Japanese immigrants tend to be included; citizenship is less relevant and a commitment to the local community becomes more important.[54]

Discover Nikkei, a project of the Japanese American National Museum, defined nikkei as follows:

We are talking about Nikkei people—Japanese emigrants and their descendants who have created communities throughout the world. The term nikkei has multiple and diverse meanings depending on situations, places, and environments. Nikkei also include people of mixed racial descent who identify themselves as Nikkei. Native Japanese also use the term nikkei for the emigrants and their descendants who return to Japan. Many of these nikkei live in close communities and retain identities separate from the native Japanese.[55]

The definition was derived from The International Nikkei Research Project, a three-year collaborative project involving more than 100 scholars from 10 countries and 14 participating institutions.[55]

Early history

Japanese emigration to the rest of Asia was noted as early as the 15th century to the Philippines;[41][56] early Japanese settlements included those in Lingayen Gulf, Manila, the coasts of Ilocos and in the Visayas when the Philippines was under the Srivijaya and Majapahit Empire. In the 16th century the Japanese settlement was established in Ayutthaya, Thailand,[57] and in early 17th century Japanese settlers was first recorded to stay in Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia). A larger wave came in the 17th century, when red seal ships traded in Southeast Asia, and Japanese Catholics fled from the religious persecution imposed by the shōguns, and settled in the Philippines, among other destinations. Many of them also intermarried with the local Filipina women (including those of pure or mixed Chinese and Spanish descent), thus forming the new Japanese-Mestizo community.[58] In the 16th and 17th centuries, thousands of traders from Japan also migrated to the Philippines and assimilated into the local population.[59] pp. 52–3 In the 15th century AD, tea-jars were brought by the shōguns to Uji in Kyoto from the Philippines which was used in the Japanese tea ceremony.[60]

After the Portuguese Empire first made contact with Japan in 1543, a large scale of slave trade developed in which Portuguese purchased Japanese as slaves in Japan and sold them to various locations overseas, including Portugal itself, throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.[61][62] Many documents mention the large slave trade along with protests against the enslavement of Japanese. Japanese slaves are believed to be the first of their nation to end up in Europe, and the Portuguese purchased large numbers of Japanese slave girls to bring to Portugal for sexual purposes, as noted by the Church in 1555. King Sebastian feared that it was having a negative effect on Catholic proselytization since the slave trade in Japanese was growing to massive proportions, so he commanded that it be banned in 1571.[63][64] Hideyoshi was so disgusted that his own people were being sold en masse into slavery on Kyushu, that he wrote a letter to Jesuit Vice-Provincial Gaspar Coelho on 24 July 1587 to demand the Portuguese, Siamese (Thai), and Cambodians stop purchasing and enslaving Japanese and return those slaves who had been removed to places as far as India.[65][66][67] Hideyoshi blamed the Portuguese and Jesuits for this slave trade and banned Christian proselytizing as a result.[68][69] Some Korean slaves in Japan who had been among the thousands of prisoners of war taken during the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–98) were bought by the Portuguese and taken to Portugal.[70][71] Fillippo Sassetti saw some Chinese and Japanese slaves in Lisbon among the large slave community in 1578, although most of the slaves were African.[72][73][74][75][76] The Portuguese "highly regarded" Asian slaves like Chinese and Japanese, much more "than slaves from sub-Saharan Africa".[77][78] The Portuguese attributed qualities like intelligence and industriousness to Chinese and Japanese slaves which is why they favored them more.[79][80][81][82] Luis Cerqueira, a Portuguese Jesuit, reported in a 1598 document that Japanese women were sold as concubines to African and European crewmembers on Portuguese ships trading in Japan.[83] Japanese slaves were brought by the Portuguese to Macau, where some of them were enslaved to Portuguese, but could also be bought by other slaves. Thus, the Portuguese might own African and Malay slaves, who in turn possessed Japanese slaves of their own.[84][85] In 1595 a law was passed by Portugal banning the sale of Chinese and Japanese slaves.[86]

From the 15th through the early 17th century, Japanese seafarers traveled to China and Southeast Asia countries, in some cases establishing early Japantowns.[87] This activity ended in the 1640s, when the Tokugawa shogunate imposed maritime restrictions which forbade Japanese from leaving the country, and from returning if they were already abroad. This policy would not be lifted for over two hundred years. Travel restrictions were eased once Japan opened diplomatic relations with Western nations. In 1867, the bakufu began issuing travel documents for overseas travel and emigration.[88]

Before 1885, fewer and fewer Japanese people emigrated from Japan, in part because the Meiji government was reluctant to allow emigration, both because it lacked the political power to adequately protect Japanese emigrants, and because it believed that the presence of Japanese as unskilled laborers in foreign countries would hamper its ability to revise the unequal treaties. A notable exception to this trend was a group of 153 contract laborers who immigrated—without official passports—to Hawai'i and Guam in 1868.[89] A portion of this group stayed on after the expiration of the initial labor contract, forming the nucleus of the nikkei community in Hawai'i. In 1885, the Meiji government began to turn to officially sponsored emigration programs to alleviate pressure from overpopulation and the effects of the Matsukata deflation in rural areas. For the next decade, the government was closely involved in the selection and pre-departure instruction of emigrants. The Japanese government was keen on keeping Japanese emigrants well-mannered while abroad in order to show the West that Japan was a dignified society, worthy of respect. By the mid-1890s, immigration companies (imin-kaisha 移民会社), not sponsored by the government, began to dominate the process of recruiting emigrants, but government-sanctioned ideology continued to influence emigration patterns.[90]

Asia

Through 1945

In 1898 the Dutch East Indies colonial government statistics showed 614 Japanese in the Dutch East Indies (166 men, 448 women).[91] During the American colonial era in the Philippines, the number of Japanese laborers working in plantations rose so high that in the 20th century, Davao City soon became dubbed as a Ko Nippon Koku ("Little Japan" in Japanese) with a Japanese school, a Shinto shrine, and a diplomatic mission from Japan. There is even a popular restaurant called "The Japanese Tunnel", which includes an actual tunnel made by the Japanese in time of the war.[92]

There was also a significant level of emigration to the overseas territories of the Empire of Japan during the Japanese colonial period, including Korea,[93] Taiwan, Manchuria, and Karafuto.[94] Unlike emigrants to the Americas, Japanese going to the colonies occupied a higher rather than lower social niche upon their arrival.[95]

In 1938 about 309,000 Japanese lived in Taiwan.[96] By the end of World War II, there were over 850,000 Japanese in Korea[97] and more than 2 million in China,[98] most of them farmers in Manchukuo (the Japanese had a plan to bring in 5 million Japanese settlers into Manchukuo).[99]

Over 400,000 people lived on Karafuto (southern Sakhalin) when the Soviet offensive began in early August 1945. Most were of Japanese or Korean descent. When Japan lost the Kuril Islands, 17,000 Japanese were expelled, most from the southern islands.[100]

After 1945

After and during World War II, most of these overseas Japanese repatriated to Japan. Like the colonization of British, so of Japanese moved to the overseas countries during World War II. The Allied powers repatriated over 6 million Japanese nationals from colonies and battlefields throughout Asia.[101] Only a few remained overseas, often involuntarily, as in the case of orphans in China or prisoners of war captured by the Red Army and forced to work in Siberia.[102] During the 1950s and 1960s, an estimated 6,000 Japanese accompanied Zainichi Korean spouses repatriating to North Korea, while another 27,000 prisoners-of-war are estimated to have been sent there by the Soviet Union; see Japanese people in North Korea.[102][103]

There is a community of Japanese people in Hong Kong largely made up of expatriate businessmen. There are about 4,018 Japanese people living in India who are mostly expatriate engineers and company executives and they are based mainly in Haldia, Bangalore and Kolkata. Additionally, there are 903 Japanese expatriates in Pakistan based mostly in the cities of Islamabad and Karachi.[104]

Americas

People from Japan began migrating to the U.S. and Canada in significant numbers following the political, cultural, and social changes stemming from the 1868 Meiji Restoration. (see Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians)

In Canada, small multi-generational communities of Japanese immigrants developed and adapted to life outside Japan.[105]

In the United States, particularly after the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, Japanese immigrants were sought by industrialists to replace Chinese immigrants. In the early years of the 20th century, anxiety about the rapid growth of cheap Japanese labor in California came to a head when in 1906, when the School Board of San Francisco passed a resolution barring children of Japanese heritage from attending regular public schools. President Roosevelt intervened to rescind the resolution, but only on the understanding that steps would be taken to put a stop to further Japanese immigration.[106] In 1907, in the face of Japanese government protests, the so-called "Gentlemen's Agreement" between the governments of Japan and the United States ended immigration of Japanese workers (i.e., men), but permitted the immigration of spouses of Japanese immigrants already in the US. The Immigration Act of 1924 banned the immigration of all but a token few Japanese, until the Immigration Act of 1965, there was very little further Japanese immigration. That which occurred was mostly in the form of war brides. The majority of Japanese settled in Hawaii, where today a third of the state's population are of Japanese descent, and the rest in the West Coast (California, Oregon, Washington, and Alaska), but other significant communities are found in the Northeast (Maine, New York, New Jersey, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New Hampshire and Pennsylvania) and Midwest (Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, Ohio, South Dakota, and Wisconsin) states.

The Japanese diaspora has been unique in the absence of new emigration flows in the second half of the 20th century.[107] However, research reports that during the post-war many Japanese migrated individually to join existing communities abroad.[108]

With the restrictions on entering the United States, the level of Japanese immigration to Latin America began to increase.[109] Mexico was the first Latin American country to receive Japanese immigrants in 1897,[110] when the first thirty five arrived in Chiapas to work on coffee farms. Immigration into Mexico died down in the following years, but was eventually spurred again in 1903 due to the acceptance of mutually recognized contracts on immigration by both countries. Immigrants coming in the first four years of these contracts worked primarily on sugar plantations, coal mines, and railroads. Unfortunately, Japanese immigrants in Mexico proved to have far less continuity than those in other South American countries, as disease, mining accidents, and discrimination caused many Japanese to pass away or simply leave without seeing their contracts through to completion. Less than 27% of the total number of Japanese who immigrated into Mexico before 1941 remained there 40 years later. [111] Japanese immigrants (particularly from the Okinawa Prefecture, including Okinawans) arrived in small numbers during the early 20th century.

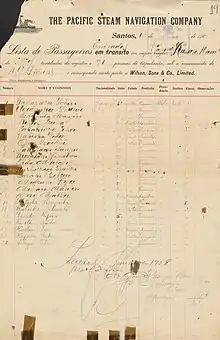

Japanese Brazilians are the largest ethnic Japanese community outside Japan (numbering about 1.5 million,[112] compared to about 1.2 million in the United States), and São Paulo contains the largest concentration of Japanese outside Japan. Paraná and Mato Grosso do Sul also have a large Japanese community. The first Japanese immigrants (791 people, mostly farmers) came to Brazil in 1908 on the Kasato Maru from the Japanese port of Kobe, moving to Brazil in search of better living conditions. Many of them ended up as laborers on coffee farms (for testimony of Kasato Maru's travelers that continued to Argentina see es:Café El Japonés, see also Shindo Renmei). Immigration of Japanese workers in Brazil was actually subsidized by São Paulo up until 1921, with around 40,000 Japanese emigrating to Brazil between the years of 1908 and 1925, and 150,000 pouring in during the following 16 years. The most immigrants to come in one year peaked in 1933 at 24,000, but restrictions due to ever growing anti-Japanese sentiment caused it to die down and then eventually halt at the start of World War II. Japanese immigration into Brazil actually saw continued traffic after it resumed in 1951. Around 60,000 entered the country during 1951 and 1981, with a sharp decline happening in the 1960s due to a resurgence of Japan's domestic economy.[111]

Japanese Peruvians form another notable ethnic Japanese community with an estimated 6,000 Issei and 100,000 Japanese descendants (Nisei, Sansei, Yonsei), and including a former Peruvian president, Alberto Fujimori. Japanese food known as Nikkei cuisine is a rich part of Peruvian-Japanese culture, which includes the use of seaweed broth and sushi-inspired versions of ceviche.[113][114]

There was a small amount of Japanese settlement in the Dominican Republic between 1956 and 1961, in a program initiated by Dominican Republic leader Rafael Trujillo. Protests over the extreme hardships and broken government promises faced by the initial group of migrants set the stage for the end of state-supported labor emigration in Japan.[115][116]

The Japanese Colombian colony migrated between 1929 and 1935 in three waves. Their community is unique in terms of their resistance against the internal conflict occurring in Colombia during the decade of the 1950s, a period known as La Violencia.[117]

Europe

The Japanese in Britain form the largest Japanese community in Europe with well over 100,000 living all over the United Kingdom (the majority being in London). In recent years, many young Japanese have been migrating from Japan to Britain to engage in cultural production and to become successful artists in London.[118] There are also small numbers of Japanese people in Russia some whose heritage date back to the times when both countries shared the territories of Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands; some Japanese communists settled in the Soviet Union, including Mutsuo Hakamada, the brother of former Japanese Communist Party chairman Satomi Hakamada whose daughter Irina Hakamada is a notable Russian political figure.[119] The 2002 Russian census showed 835 people claiming Japanese ethnicity (nationality).[120]

There is a sizable Japanese community in Düsseldorf, Germany of nearly 8,000.[121]

Oceania

Early Japanese immigrants were particularly prominent in Broome, Western Australia, where until the Second World War they were the largest ethnic group, who were attracted to the opportunities in pearling. Several streets of Broome have Japanese names, and the town has one of the largest Japanese cemeteries outside Japan. Other immigrants were involved in the sugar cane industry in Queensland. During the Second World War, the Japanese population was detained and later expelled at the cessation of hostilities. The Japanese population in Australia was later replenished in the 1950s by the arrival of 500 Japanese war brides, who had married AIF soldiers stationed in occupied Japan.In recent years, Japanese migration to Australia, largely consisting of younger age females, has been on the rise.[122]

There is also a small but growing Japanese community in New Zealand, primarily in Auckland and Wellington.

In the census of December 1939, the total population of the South Seas Mandate was 129,104, of which 77,257 were Japanese. By December 1941, Saipan had a population of more than 30,000 people, including 25,000 Japanese.[123] There are Japanese people in Palau, Guam and Northern Mariana Islands.

Return migration to Japan

In the 1980s, with Japan's growing economy facing a shortage of workers willing to do so-called three K jobs (きつい kitsui [difficult], 汚い kitanai [dirty], and 危険 kiken [dangerous]), Japan's Ministry of Labor began to grant visas to ethnic Japanese from South America to come to Japan and work in factories. The vast majority—estimated at roughly 300,000—were from Brazil, but there is also a large population from Peru and smaller populations from Argentina and other Latin American countries.

In response to the recession as of 2009, the Japanese government offered ¥300,000 ($3,300) for unemployed Japanese descendants from Latin America to return to their country of origin with the stated goal of alleviating the country's soaring unemployment. Another ¥200,000 ($2,200) is offered for each additional family member to leave.[124] Emigrants who take this offer are not allowed to return to Japan with the same privileged visa with which they entered the country.[125] Arudou Debito, columnist for The Japan Times, an English language newspaper in Japan, denounced the policy as "racist" as it only offered Japanese-blooded foreigners who possessed the special "person of Japanese ancestry" visa the option to receive money in return for repatriation to their home countries.[125] Some commentators also accused it of being exploitative since most nikkei had been offered incentives to immigrate to Japan in 1990, were regularly reported to work 60+ hours per week, and were finally asked to return home when the Japanese became unemployed in large numbers.[125][126][127] At the same time, return migration to Japan, along with repatriation to their home countries, has also created complex relationships with both their homeland and hostland, a condition which has been called a "'squared diaspora' in which the juxtaposition of homeland and hostland itself becomes questionable, instable and fluctuating."[128] This has also taken on new forms of "circular migration" as first and second generation nikkei travel back and forth between Japan and their home countries.[129]

Major cities with significant populations of Japanese nationals

- São Paulo, Brazil: 693,495

- Los Angeles, United States: 68,744

- Bangkok, Thailand: 52,871

- New York City, United States: 46,137

- Shanghai, China: 43,455

- Singapore: 36,423

- Greater London, United Kingdom: 34,298

- Sydney, Australia: 32,189

- Vancouver, Canada: 26,910

- Hong Kong, China: 25,004

- Londrina, Brazil: 25,000

- Melbourne, Australia: 19,878

- San Francisco, United States: 18,862

- Honolulu, United States: 16,306

- Paris, France: 15,684

- San Jose, United States: 14,761

- Toronto, Canada: 13,725

- Seoul, South Korea: 12,655

- Seattle, United States: 12,548

- Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: 12,539

- Chicago, United States: 11,928

- Manila, Philippines

- Davao City, Philippines

Note: The above data shows the number of Japanese nationals living overseas as of October 1, 2017, according to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan.[130]

See also

References

- The Association of Nikkei & Japanese Abroad. "Who are "Nikkei & Japanese Abroad"?".

- "Japan-Brazil Relations (Basic Data)". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- "Who are Nikkei & Japanese Abroad?". The Association Of Nikkei And Japanese Abroad. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- "ブラジル基礎データ | 外務省". 外務省.

- Data Access and Dissemination Systems (DADS). "U.S. Census website". census.gov. Retrieved 13 August 2018.

- "Annual Report of Statistics on Japanese Nationals Overseas" (PDF). Mofa.go.jp. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- Agnote, Dario (11 October 2006). "A glimmer of hope for castoffs". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- Ohno, Shun (2006). "The Intermarried issei and mestizo nisei in the Philippines". In Adachi, Nobuko (ed.). Japanese diasporas: Unsung pasts, conflicting presents, and uncertain futures. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-135-98723-7.

- "Japanese Canadians". Retrieved 14 April 2018.

- "Japan-Peru Relations". mofa.go.jp. 27 November 2012. Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- "海外在留邦人数調査統計" (PDF). mofa.go.jp. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- (PDF) https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Migration-Integration/Publikationen/Downloads-Migration/auslaend-bevoelkerung-2010200197004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Japan-Argentine Relations". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan.

- "Argentina inicia una nueva etapa en su relación con Japón". Telam.com.ar. Retrieved 21 November 2016.

- "MOFA Japan". 9 December 2019.

- Itoh, p. 7.

- "통계 - 국내 체류외국인 140만명으로 다문화사회 진입 가속화". dmcnews.kr. Archived from the original on 26 January 2016.

- Department of Immigration and Citizenship (February 2014). "Community Information Summary" (PDF). Department of Social Services. Australian Government. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2019. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- Lizcano Fernández, Francisco (May–August 2005). "Composición Étnica de las Tres Áreas Culturales del Continente Americano al Comienzo del Siglo XXI" (PDF). Revista Convergencia (in Spanish). 12 (38): 201. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2013. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- "MOFA Japan". 3 December 2014.

- "海外在留邦人数調査統計(平成28年要約版)" [Annual Report of Statistics on Japanese Nationals Overseas (Heisei 28 Summary Edition)] (PDF) (in Japanese). 1 October 2015. p. 32. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- "マレーシア基礎データ | 外務省". 外務省.

- https://www.mofa.go.jp/region/asia-paci/taiwan/data.html

- "Letter from the Embassy of the Federated States of Micronesia" (PDF). Mra.fm. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- "インドネシア基礎データ | 外務省". 外務省.

- "5. – Japanese – Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand". teara.govt.nz.

- "ボリビア基礎データ | 外務省". 外務省.

- "インド(India)". Mofa.go.jp. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- See also Japanese people in India

- "Tourism New Caledonia - Prepare your trip in New Caledonia" (PDF). newcaledonia.co.nz. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 October 2008.

- "外務省: ご案内- ご利用のページが見つかりません" (PDF). mofa.go.jp.

- "Japan-Paraguay Relations". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan.

- Rachel Pritchett. "Pacific Islands President, Bainbridge Lawmakers Find Common Ground". BSUN. Archived from the original on 16 July 2011.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Macau Population Census". Census Bureau of Macau. May 2012. Retrieved 22 July 2016.

- "ウルグアイ基礎データ | 外務省". 外務省.

- "コロンビア基礎データ | 外務省". 外務省.

- http://www.mofa.go.jp/region/latin/chile/index.html

- "キューバ共和国基礎データ". Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- "Qatar's population - by nationality". bq Magazine. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014.

- Manansala, Paul Kekai (5 September 2006). "Quests of the Dragon and Bird Clan: Luzon Jars (Glossary)".

- Cole, Fay-Cooper (1912). "Chinese Pottery in the Philippines" (PDF). Field Museum of Natural History. Anthropological Series. 12 (1).

- "Philippines History, Culture, Civilization and Technology, Filipino". asiapacificuniverse.com.

- さや・白石; Shiraishi, Takashi (1993). The Japanese in Colonial Southeast Asia. ISBN 9780877274025.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA), Japan: Japan-Mexico relations

- Palm, Hugo. "Desafíos que nos acercan," Archived 15 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine El Comercio (Lima, Peru). 12 March 2008.

- Azuma, Eiichiro (2005). "Brief Historical Overview of Japanese Emigration". International Nikkei Research Project. Retrieved 2 February 2007.

- Furia, Reiko (1993). "The Japanese Community Abroad: The Case of Prewar Davao in the Philippines". In Saya Shiraishi; Takashi Shiraishi (eds.). The Japanese in Colonial Southeast Asia. Southeast Asia Program, Cornell University Publications. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-87727-402-5. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- Shoji, Rafael (2005). "Book Review" (PDF). Journal of Global Buddhism 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2007.

- "海外在留邦人数調査統計" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 July 2018. Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- International Nikkei Research Project (2007). "International Nikkei Research Project". Japanese American National Museum. Retrieved 2 February 2007.

- Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.1) (2007). "nikkei". Random House, Inc. Retrieved 2 February 2007.

- Komai, Hiroshi (2007). "Japanese Policies and Realities" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 2 February 2007.

- Manzenreiter, Wolfram (27 July 2017). "Squared diaspora: Representations of the Japanese diaspora across time and space". Contemporary Japan. 29 (2): 106–116. doi:10.1080/18692729.2017.1351021.

- Discover Nikkei (2007). "What is Nikkei?". Japanese American National Museum. Retrieved 19 January 2007.

- Philippines History, Culture, Civilization and Technology, Filipino. Asiapacificuniverse.com. Retrieved on 2013-08-24.

- "Village Ayutthaya". thailandsworld.com. Archived from the original on 21 December 2014.

- "Paco". Page Nation. Archived from the original on 7 May 2010.

- Leupp, Gary P. (1 January 2003). Interracial Intimacy in Japan. ISBN 9780826460745.

- Manansala, Paul Kekai (5 September 2006). "Quests of the Dragon and Bird Clan: Luzon Jars (Glossary)".

- HOFFMAN, MICHAEL (26 May 2013). "The rarely, if ever, told story of Japanese sold as slaves by Portuguese traders". The Japan Times. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- "Europeans had Japanese slaves, in case you didn't know ..." Japan Probe. 10 May 2007. Archived from the original on 13 June 2010. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- Nelson, Thomas (Winter 2004). "Monumenta Nipponica (Slavery in Medieval Japan)". Monumenta Nipponica. 59 (4): 463–492. JSTOR 25066328.

- Nelson, Thomas (Winter 2004). "Slavery in Medieval Japan". Monumenta Nipponica. 59 (4): 463–492. JSTOR 25066328.

- Nelson, Thomas (Winter 2004). "Slavery in Medieval Japan". Monumenta Nipponica. 59 (4): 465. JSTOR 25066328.

- Joseph Mitsuo Kitagawa (2013). Religion in Japanese History (illustrated, reprint ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-231-51509-2. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- Donald Calman (2013). Nature and Origins of Japanese Imperialism. Routledge. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-134-91843-0. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- Gopal Kshetry (2008). FOREIGNERS IN JAPAN: A Historical Perspective. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 978-1-4691-0244-3. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- J F Moran, J. F. Moran (2012). Japanese and the Jesuits. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-88112-3. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- Robert Gellately; Ben Kiernan, eds. (2003). The Specter of Genocide: Mass Murder in Historical Perspective (reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 277. ISBN 978-0-521-52750-7. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

Hideyoshi korean slaves guns silk.

- Gavan McCormack (2001). Reflections on Modern Japanese History in the Context of the Concept of "genocide". Edwin O. Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies. Harvard University, Edwin O. Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies. p. 18. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- Jonathan D. Spence (1985). The memory palace of Matteo Ricci (illustrated, reprint ed.). Penguin Books. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-14-008098-8. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

countryside.16 Slaves were everywhere in Lisbon, according to the Florentine merchant Filippo Sassetti, who was also living in the city during 1578. Black slaves were the most numerous, but there were also a scattering of Chinese

- José Roberto Teixeira Leite (1999). A China no Brasil: influências, marcas, ecos e sobrevivências chinesas na sociedade e na arte brasileiras (in Portuguese). UNICAMP. Universidade Estadual de Campinas. p. 19. ISBN 978-85-268-0436-4. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

Idéias e costumes da China podem ter-nos chegado também através de escravos chineses, de uns poucos dos quais sabe-se da presença no Brasil de começos do Setecentos.17 Mas não deve ter sido através desses raros infelizes que a influência chinesa nos atingiu, mesmo porque escravos chineses (e também japoneses) já existiam aos montes em Lisboa por volta de 1578, quando Filippo Sassetti visitou a cidade,18 apenas suplantados em número pelos africanos. Parece aliás que aos últimos cabia o trabalho pesado, ficando reservadas aos chins tarefas e funções mais amenas, inclusive a de em certos casos secretariar autoridades civis, religiosas e militares.

- Jeanette Pinto (1992). Slavery in Portuguese India, 1510–1842. Himalaya Pub. House. p. 18. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

... Chinese as slaves, since they are found to be very loyal, intelligent and hard working' ... their culinary bent was also evidently appreciated. The Florentine traveller Fillippo Sassetti, recording his impressions of Lisbon's enormous slave population circa 1580, states that the majority of the Chinese there were employed as cooks.

- Charles Ralph Boxer (1968). Fidalgos in the Far East 1550–1770 (2, illustrated, reprint ed.). 2, illustrated, reprint. p. 225. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

be very loyal, intelligent, and hard-working. Their culinary bent (not for nothing is Chinese cooking regarded as the Asiatic equivalent to French cooking in Europe) was evidently appreciated. The Florentine traveller Filipe Sassetti recording his impressions of Lisbon's enormous slave population circa 1580, states that the majority of the Chinese there were employed as cooks. Dr. John Fryer, who gives us an interesting ...

- José Roberto Teixeira Leite (1999). A China No Brasil: Influencias, Marcas, Ecos E Sobrevivencias Chinesas Na Sociedade E Na Arte Brasileiras (in Portuguese). UNICAMP. Universidade Estadual de Campinas. p. 19. ISBN 978-85-268-0436-4. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- Paul Finkelman (1998). Paul Finkelman, Joseph Calder Miller (ed.). Macmillan encyclopedia of world slavery, Volume 2. Macmillan Reference USA, Simon & Schuster Macmillan. p. 737. ISBN 978-0-02-864781-4. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- Finkelman & Miller 1998, p. 737

- Duarte de Sande (2012). Derek Massarella (ed.). Japanese Travellers in Sixteenth-century Europe: A Dialogue Concerning the Mission of the Japanese Ambassadors to the Roman Curia (1590). Works Issued by the Hakluyt Society. Third Series. Volume 25 of 3: Works, Hakluyt Society Hakluyt Society. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4094-7223-0. ISSN 0072-9396. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- A. C. de C. M. Saunders (1982). A Social History of Black Slaves and Freedmen in Portugal, 1441–1555. Volume 25 of 3: Works, Hakluyt Society Hakluyt Society (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-521-23150-3. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- Jeanette Pinto (1992). Slavery in Portuguese India, 1510–1842. Himalaya Pub. House. p. 18. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- Charles Ralph Boxer (1968). Fidalgos in the Far East 1550–1770 (2, illustrated, reprint ed.). Oxford U.P. p. 225. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- Michael Weiner, ed. (2004). Race, Ethnicity and Migration in Modern Japan: Imagined and imaginary minorities (illustrated ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 408. ISBN 978-0-415-20857-4. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- Kwame Anthony Appiah; Henry Louis Gates, Jr., eds. (2005). Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience (illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 479. ISBN 978-0-19-517055-9. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- Anthony Appiah; Henry Louis Gates, eds. (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa, Volume 1 (illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-19-533770-9. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- Dias 2007, p. 71

- "JANM/INRP - Harumi Befu". janm.org.

- "外務省: 外交史料 Q&A その他". Mofa.go.jp. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- Known as the Gannen-mono (元年者), or "first year people" because they left Japan in the first year of the Meiji Era. Jonathan Dresner, "Instructions to Emigrant Laborers, 1885–1894: 'Return in Triumph' or 'Wander on the Verge of Starvation,'" In Japanese Diasporas: Unsung Pasts, Conflicting Presents, and Uncertain Futures, ed. Nobuko Adachi (London: Routledge, 2006), 53.

- Dresner, 52-68.

- Shiraishi & Shiraishi 1993, p. 8

- "A Little Tokyo Rooted in the Philippines". Philippines: Pacific Citizen. April 2007. Archived from the original on 22 February 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Japanese Periodicals in Colonial Korea". columbia.edu.

- Japanese Immigration Statistics Archived 15 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, DiscoverNikkei.org

- Lankov, Andrei (23 March 2006). "The Dawn of Modern Korea (360): Settling Down". The Korea Times. Retrieved 18 December 2006.

- Grajdanzev, A. J. (22 August 2017). "Formosa (Taiwan) Under Japanese Rule". Pacific Affairs. 15 (3): 311–324. doi:10.2307/2752241. JSTOR 2752241.

- "Monograph Paper 3. Section 13". usc.edu. Archived from the original on 13 October 1999.

- Killing of Chinese in Japan concerned, China Daily

- Prasenjit Duara: The New Imperialism and the Post-Colonial Developmental State: Manchukuo in comparative perspective Archived 23 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "The Kurile Islands Dispute". Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- When Empire Comes Home : Repatriation and Reintegration in Postwar Japan by Lori Watt, Harvard University Press

- "Russia Acknowledges Sending Japanese Prisoners of War to North Korea". Mosnews.com. 1 April 2005. Archived from the original on 13 November 2006. Retrieved 23 February 2007.

- Morris-Suzuki, Tessa (13 March 2007). "The Forgotten Victims of the North Korean Crisis". Nautilus Institute. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 15 March 2007. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "パキスタン・イスラム共和国基礎データ". 各国・地域情勢. Tokyo, Japan: Ministry of Foreign Affairs. July 2009. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- Ikawa, Fumiko (February 1963). "Reviews: Umi o Watatta Nippon no Mura by Masao Gamo and "Steveston Monogatari: Sekai no Naka no Nipponjin" by Kazuko Tsurumi". American Anthropologist. New Series, Vol. 65 (1): 152–156. doi:10.1525/aa.1963.65.1.02a00240. JSTOR 667278.

- Chaurasia, Radhey (2003). History of Japan. New Delhi: Atlantic. p. 136. ISBN 978-81-269-0228-6.

- Maidment, Richard et all. (1998). Culture and Society in the Asia-Pacific, p. 80.

- A. Diaz Collazos. "The Colombian Nikkei and the Narration of Selves". academia.edu.

- Manzenreiter, Wolfram (17 July 2017). "Living under more than one sun: The Nikkei Diaspora in the Americas". Contemporary Japan. 29 (2): 193–213. doi:10.1080/18692729.2017.1351045.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan (2012). "Japan-Mexico foreign relations". MOFA. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- Tigner, James L. (1981). "Japanese Immigration into Latin America: A Survey". Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs. 23 (4): 457–482. doi:10.2307/165454. ISSN 0022-1937. JSTOR 165454.

- Japan-Brazil Relations. MOFA. Retrieved on 2013-08-24.

- Takenaka, Ayumi (2017). "Immigrant integration through food: Nikkei cuisine in Peru". Contemporary Japan. 29 (2): 117–131. doi:10.1080/18692729.2017.1351022. S2CID 134330815.

- "Salmon with Chenin Blanc" Wine Spectator (March 31, 2020), p. 100

- Horst, Oscar H.; Asagiri, Katsuhiro (July 2000). "The Odyssey of Japanese Colonists in the Dominican Republic". Geographical Review. 90 (3): 335–358. doi:10.2307/3250857. JSTOR 3250857.

- Azuma, Eiichiro (2002). "Historical Overview of Japanese Emigration, 1868–2000". In Kikumura-Yano, Akemi (ed.). Encyclopedia of Japanese Descendants in the Americas: An Illustrated History of the Nikkei. Rowman Altamira. pp. 32–48. ISBN 978-0-7591-0149-4.

- "The Colombian Nikkei and the Narration of Selves - Part 1 of 4". Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- Fujita, Yuiko (2009). Cultural Migrants from Japan: Youth, Media, and Migration in New York and London. MD, United States: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-2891-6.

- Mitrokhin, Vasili; Christopher, Andrew (2005). The World Was Going Our Way: The KGB and the Battle for the Third World. Tennessee, United States: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00311-2.

- Владение языками (кроме русского) населением отдельных национальностей по республикам, автономной области и автономным округам Российской Федерации (in Russian). Федеральная служба государственной статистики. Archived from the original (Microsoft Excel) on 4 November 2006. Retrieved 1 December 2006.

- "Website of the Japanese Generalkonsulat: Japaner in Düsseldorf. 27 May 2009". Archived from the original on 19 November 2009. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- Deborah McNamara and James E. Coughlan (1992). "Recent Trends in Japanese Migration to Australia and the Characteristics of Recent Japanese Immigrants Settling in Australia". Faculty of Arts, Education, and Social Sciences, James Cook University. Archived from the original on 1 October 2006. Retrieved 2006-12-21. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - A Go: Another Battle for Sapian Archived 23 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Perry, Joellen. "The Czech Republic Pays for Immigrants to Go Home Unemployed Guest Workers and Their Kids Receive Cash and a One-Way Ticket as the Country Fights Joblessness," Wall Street Journal. 28 April 2009.

- Arudou, Debito (7 April 2009). "Golden parachutes' mark failure of race-based policy". The Japan Times. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- Coco Masters/Tokyo (20 April 2009). "Japan to Immigrants: Thanks, But You Can Go Home Now". Time. Retrieved 4 December 2009.

- Manzenreiter, Wolfram (2017). "Living under more than one sun: The Nikkei Diaspora in the Americas". Contemporary Japan. 29 (2): 193–213. doi:10.1080/18692729.2017.1351045.

- Sueyoshi, Ana (2017). "Intergenerational circular migration and differences in identity building of Nikkei Peruvians". Contemporary Japan. 29 (2): 230–245. doi:10.1080/18692729.2017.1351047. S2CID 158944843.

- "(Annual Report of Statistics on Japanese Nationals Overseas" (PDF). Retrieved 27 May 2019.

Bibliography

- Dias, Maria Suzette Fernandes (2007), Legacies of slavery: comparative perspectives, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, p. 238, ISBN 978-1-84718-111-4

- Maidment, Richard A. and Colin Mackerras. (1998). Culture and Society in the Asia-Pacific. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-17278-3

- Sakai, Junko. (2000). Japanese Bankers in the City of London: Language, Culture and Identity in the Japanese Diaspora. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-19601-7

- Fujita, Yuiko (2009) Cultural Migrants from Japan: Youth, Media, and Migration in New York and London. MD: Lexington Books, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 978-0-7391-2891-6

- Masterson, Daniel M. and Sayaka Funada-Classen. (2004), The Japanese in Latin America: The Asian American Experience. Urbana, Illinois: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-07144-7; OCLC 253466232

- Manzenreiter, Wolfram (2017). "Squared diaspora: Representations of the Japanese diaspora across time and space". Contemporary Japan. 29 (2): 106–116. doi:10.1080/18692729.2017.1351021.

- Niiya, Brian, ed. Encyclopedia of Japanese American History: An A-to-Z Reference from 1868 to the Present. (2001). online free to borrow

- Sueyoshi, Ana (2017). "Intergenerational circular migration and differences in identity building of Nikkei Peruvians". Contemporary Japan. 29 (2): 230–245. doi:10.1080/18692729.2017.1351047. S2CID 158944843.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Japanese diaspora. |

- Discover Nikkei, A site co-ordinated with the Japanese American National Museum and affiliated with academic, community programs, and scholars.

- Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA): Future Policy Regarding Cooperation with Overseas Communities of Nikkei

- APJ, A non-profit organization representing Japanese Citizens living in Peru and their descendants.

- NikkeiCity, Information of the nikkei in Peru.

- Nikkei Youth Network, A network of nikkei leaders around the world.

- Japanese Canadians Photograph Collection – A photo album from the UBC Library Digital Collections depicting the life of Japanese Canadians in British Columbia during World War II

- ハルとナツ, a TV drama based on historical events aired by NHK in October 2005.

- Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection, Hoover Institution Library & Archives Japanese Diaspora Initiative.