Indian philosophy

Indian philosophy refers to philosophical traditions which developed in the Indian subcontinent. Modern scholars generally divide the field between "Hindu Philosophy" (also known as "Brahmanical Philosophy") and non-Hindu traditions such as Buddhist Philosophy and Jain Philosophy.[1] This division is generally derived from traditional Indian classifications.

| Part of a series on |

| Philosophy |

|---|

Left to right: Plato, Kant, Nietzsche, Buddha, Confucius, Averroes |

| Branches |

| Periods |

| Traditions |

|

Traditions by region Traditions by school Traditions by religion |

| Literature |

|

| Philosophers |

| Lists |

| Miscellaneous |

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Eastern philosophy |

|---|

|

There are numerous different Indian schools of thought, all of which debated and influenced each other throughout Indian history. Most Indian philosophical discourse took place in Sanskrit, but also extends to other languages such as various Prakrits, and other Asian Languages (mainly for Buddhist discourse).

Indian philosophical texts include extensive discussions on ontology (metaphysics, Brahman-Atman, Sunyata-Anatta), reliable means of knowledge (epistemology, pramana), ethics (which is often influenced by the Indian idea of karma), value system (axiology) and other topics.[2][3][4]

The main schools of Indian philosophy were formalized chiefly between 1000 BCE to the early centuries of the Common Era. Competition and integration between the various schools were intense during their formative years, especially between 800 BCE and 200 CE. Today, the Hindu Philosophical schools are most influential in India, while the Buddhist tradition remains influential in the Himalayan regions, East Asia and Southeast Asia.

Themes and classifications

Common Themes

Indian philosophies share many concepts such as dharma (an ultimate principle or truth), karma (ethical action), pramana (epistemic warrant), the nature and existence (or not) of the atman (eternal self), samsara (the round of rebirth), reincarnation (or rebirth), dukkha (suffering), ahimsa (nonviolence), renunciation, meditation (dhyana), with almost all of them focusing on the ultimate goal of liberation of the individual through diverse range of spiritual practices (moksha, nirvana).[5]

They differ in their assumptions about the nature of existence as well as the specifics of the path to the ultimate liberation, resulting in numerous schools that disagreed with each other. Their ancient doctrines span the diverse range of philosophies found in other ancient cultures.[6]

Classification

A traditional Brahmanical classification divides orthodox (āstika) and heterodox (nāstika) schools of philosophy, depending on one of three alternate criteria: whether it believes the Vedas as a valid source of knowledge; whether the school believes in the premises of Brahman and Atman; and whether the school believes in afterlife and devas.[7][8][9]

From this Hindu point of view, there are six major schools of orthodox (astika) Indian Hindu philosophy—Nyaya, Vaisheshika, Samkhya, Yoga, Mīmāṃsā and Vedanta, and five major heterodox (nastika) schools—Jain, Buddhist, Ajivika, Ajñana, and Charvaka. However, there are other methods of classification; Vidyaranya for instance identifies sixteen schools of Indian philosophy by including those that belong to the Śaiva and Raseśvara traditions.[10][11]

Buddhist traditions meanwhile have their own doxographical categories. The main division is between Buddhists (who accept the word of the Buddha as authoritative in some way) and non-Buddhists (who do not accept the Buddhist teachings) which are labeled "tīrthikas" (forders, i.e. those who are, unsuccessfully, trying to make a ford to cross the river of samsara). For example, in Tibetan Buddhist classifications, which are derived from medieval Indian Buddhism, the main doxographical division is between the "The Buddha Dharma of the insiders" (which includes all the main Buddhist schools like Theravada, Vaibhasika, Sautrantika, Yogacara and Madhyamaka) and the Dharma systems of the "outsiders".[12]

Hindu philosophy

Vedic Philosophy

The Vedas are the oldest texts of the Indian tradition. They contain the main ideas, rituals and hymns of the Historical Vedic Religion. These ideas were the main source for the philosophies of the various Hindu schools of thought.[14]

The earliest portion of the Vedas are termed the karma khaṇḍa, and includes hymns (Samhitas) and descriptions of rituals (Brahmanas). Key concepts which are found in these sections which later influenced the development of Hindu thought include the idea of Rta (cosmic harmony or universal order) and Brahman (an ultimate metaphysical principle).[15] Other ideas found in the karma khaṇḍa include the necessity of ritual sacrifices (yajna), which includes animal sacrifice, and the division of society into castes or varnas (which can be found in the Puruṣa Sūkta).[14]

Regarding theology, the Vedas do not present a single theological position. Instead, one can find multiple views and ideas regarding the gods and scholars have pointed out verses that can support monotheism, henotheism, polytheism and pantheism.[16]

The most philosophical texts found in the Vedas are the Upaniṣads, which are also termed uttara mīmāṃsā (“higher inquiry”), or the vedānta (the end of the Vedas). These texts focus on metaphysical, axiological and cosmological issues, such as the ideas of Atman (the eternal individual self) and Brahman (here seen as the universal consciousness). The Upaniṣads associate Brahman with the cosmos, and further associate Brahman with Atman. They also include discussions on the nature of dharma and karma, on Māyā, on how to gain jñāna (knowledge), and on how to reach moksha (liberation).[14][17] The different Upaniṣads also provide a variety of philosophical perspectives, from monism to dualism.[18]

Vedic thought was further developed in other later texts (sometimes termed the Smṛti Literature), the most popular and important of which are the Mahābhārata and the Rāmāyana. While these are generally epic narratives, they include philosophical themes, and in some sections, are purely focused on philosophical exposition. The Bhagavad Gītā is the most influential of these philosophical discussions.[14] One of the key ideas in these works is the ethics of Varna (varna) and life station (āśrama) and how this ethic relates to Dharma, yoga, and mokṣa. The Bhagavad Gītā presents these ideas alongside the idea of svadharma (one's own duty or individual role), which refers to an individual's duty in life which is based on their varna and birth. The Bhagavad Gītā exhorts individuals to follow their duty without attachment, and this is seen as true renunciation (which is important in order to reach mokṣa). The text also discusses the nature of God, and the practice of the yoga of devotion (bhakti).[14]

The Six Schools

After the Vedic period, a series of philosophical traditions developed among the Sanskrit literate classes (mainly Brahmins). Their ideas were closely influenced by the philosophies of the Vedas and the Upanishads, but also by the ideas of the Śramaṇa schools (to a lesser extent). The philosophers working in these traditions wrote new philosophical texts, which are often called "sutras". Some of these philosophical schools (called darśanas, "worldviews") are often classified into a standard list of six "orthodox" (Astika) darśanas, all of which accept the testimony of the Vedas.

These "Six Philosophies" (ṣaḍ-darśana) are:[19][20][21]

- Sāṃkhya, a philosophical tradition which regards the universe as consisting of two independent realities: puruṣa ('consciousness') and prakṛti ('matter') and which attempts to develop a metaphysics based on this duality.[22] It has included atheistic authors as well as some theistic thinkers.

- Yoga, a school similar to Sāṃkhya (or perhaps even a branch of it) which accepts a personal god and focuses on yogic practice.[23]

- Nyāya, a philosophy which focuses on logic and epistemology. It accepts six kinds of pramanas (epistemic warrants): (1) perception, (2) inference, (3) comparison and analogy, (4) postulation, derivation from circumstances, (5) non-perception, negative/cognitive proof and (6) word, testimony of past or present reliable experts. Nyāya defends a form of direct realism and a theory of substances (dravya).[24][25]

- Vaiśeṣika, closely related to the Nyāya school, this tradition focused on the metaphysics of substance, and on defending a theory of atoms.[26][27] Unlike Nyāya, they only accept two pramanas: perception and inference.

- Pūrva-Mīmāṃsā, a school which focuses on exegesis of the Vedas, philology and the interpretation of Vedic ritual.[28][29]

- Vedānta (also called Uttara Mīmāṃsā), focuses on interpreting the philosophy of the Upanishads, particularly the metaphysical ideas relating to Atman and Brahman.[30][31]

Sometimes these groups are often coupled into three groups for both historical and conceptual reasons: Nyāya-Vaiśeṣika, Sāṃkhya-Yoga, and Mīmāṃsā-Vedānta.

Each tradition included different currents and sub-schools, for example, Vedānta was divided among the sub-schools of Advaita (non-dualism), Visishtadvaita (qualified non-dualism), Dvaita (dualism), Dvaitadvaita (dualistic non-dualism), Suddhadvaita, and Achintya Bheda Abheda (inconceivable oneness and difference).

Other Hindu traditions

While the Vedic based "Six Darśanas" were extremely influential systems of thought in India, there were other systems which were also quite influential. The philosophical schools of Shaivism are often classified separately because of their commitment to texts other than the Vedas, mainly the Shaiva Agamas and Shaiva Tantras. There are several schools of Shaiva thought such as:

- Pāśupata, a theistic tradition of devotion and asceticism derived from the Pāśupatasūtra

- Śaiva siddhānta, a theistic and tantric tradition with a theology that presents three universal realities: the pashu (individual soul), the pati (the lord, Shiva), and the pasha (soul’s bondage) through ignorance, karma and maya. It focuses on ritual action as a means to achieve liberation.

- The Pratyabhijñā philosophy of Trika Shaivism (also known as Kashmir Shaivism), which defends a form of monistic idealism. This tradition rejects the Advaita Vedanta view that says the world is an illusion (maya), instead it sees the world as being created by the vibration (spanda) of the single universal consciousness. This is generally associated with Shaiva-Shakta Tantra.

There are also other minor schools which are mentioned by Indian scholars like Vidyāraṇya. These include traditions such as Raseśvara (which focused on alchemical ideas which make use of mercury) and the linguistic philosophies of Pāṇini and Bhartṛhari.[10]

Jain philosophy

Jainism is a Śramaṇic religion which rejected the authority of the Vedas and the brahmins. Its core philosophy is based on karma, rebirth, samsara and moksha. Jainism can be traced back through the lineage of 24 Tirthankars (preachers of Dharma). The first tirthankar Lord Rishabhdeva is regarded as the traditional founder of Jainism and the father of human civilization in the current time cycle. Historically, the 24th tirthankar Lord Mahavira lived in 6th century BCE and Lord Parshvanatha in around 8th century BCE.[32][33] Jainism places strong emphasis on strict asceticism, ahimsa (non-violence) and ethical vegetarianism as a means of purifying the soul of dark karma. These ideas influenced other Indian traditions including Buddhism and Hinduism.[34]

Jain philosophy is mainly a dualistic system which holds that there are two uncreated substances in the universe, unconscious matter (ajīva) and conscious souls (jīva) which are infinite in number.[35] Karma is seen as a subtle matter which pollutes the souls and keep them bound to the cycle of transmigration.[36] Jain practices stop the flow of karma into the soul, which leads to purification and eventually to spiritual liberation. For Jains, the universe is uncreated and has always existed, and thus Jainism rejects any theory of a creator deity or salvation through a god.[37]

Another central doctrine of Jain thought is the doctrine of Anekantavada (relativity of viewpoints, many-sidedness, literally: "not-one-sided"). This doctrine holds that ultimate reality can only be understood from a multiplicity of viewpoints and perspectives.[38]

Jain philosophy is outlined in the Tattvārthasūtra of Umaswati (possibly between 2nd-century and 5th-century CE), which is one of the most authoritative texts in the tradition. The views found in this text are fairly standard among the different Jain traditions and are shared by both the Śvetāmbara and Digambara sects.[39]

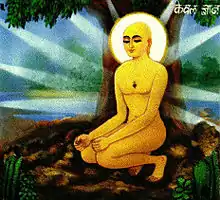

Buddhist philosophy

.jpeg.webp)

Buddhist philosophy is a system of thought which started with the teachings of the Buddha, or "awakened one", also known as Gautama Buddha or Shakyamuni (the sage of the Shakya clan). Buddhism is founded on elements of the Śramaṇa movement, which flowered in the first half of the 1st millennium BCE. Buddhism and the other Indian philosophical schools mutually influenced each other and shared many concepts (such as karma, samsara, rebirth, and spiritual liberation).[40]

However, Buddhist thought rejects foundational Vedic concepts such Brahman, Atman, the divine source of the castes, the authority of the Vedas and the usefulness of Vedic ritual.[41][42][43] Instead, Buddhism affirms the impermanence of all conditioned phenomena, (including one's consciousness, and all other processes which make up a person) and thus rejects an eternal self, soul or consciousness in favor of the theory of not-self (anatman) and dependent origination (pratītyasamutpāda).[44][45]

After the death of the Buddha, several competing philosophical systems termed Abhidharma began to emerge as ways to systematize Buddhist philosophy.[46] The Mahayana movement also arose (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and included new ideas and scriptures.

The main traditions of Buddhist philosophy in India (from 300 BCE to 1000 CE) were:[46]:xxiv

- The Mahāsāṃghika ("Great Community") tradition (which included numerous sub-schools, all are now extinct)

- The schools of the Sthavira ("Elders") tradition:

- Vaibhāṣika ("Commentators") also known as the Sarvāstivāda-Vaibhāśika, was an Abhidharma tradition that composed the "Great Commentary" (Mahāvibhāṣa). They were known for their defense of the doctrine of "sarvāstitva" (all exists), which is a form of eternalism regarding the philosophy of time. They also supported direct realism and a theory of substances (svabhāva).

- Sautrāntika ("Those who uphold the sutras"), a tradition which did not see the Abhidharma as authoritative, and instead focused on the Buddhist sutras. They disagreed with the Vaibhāṣika on several key points, including their eternalistic theory of time.

- Pudgalavāda ("Personalists"), which were known for their controversial theory of the "person" (pudgala), now extinct.

- Vibhajyavāda ("The Analysts"), a widespread tradition which reached Kashmir, South India and Sri Lanka. A part of this school has survived into the modern era as the Theravada tradition. Their orthodox positions can be found in the Kathavatthu. They rejected the views of the Pudgalavāda and of the Vaibhāṣika among others.

- The schools of the Mahāyāna ("Great Vehicle") tradition (which continue to influence Tibetan and East Asian Buddhism)

- Madhyamaka ("Middle way" or "Centrism") founded by Nagarjuna. Also known as Śūnyavāda (the emptiness doctrine) and Niḥsvabhāvavāda (the no svabhāva doctrine), this tradition focuses on the idea that all phenomena are empty of any essence or substance (svabhāva).

- Yogācāra ("Yoga praxis"), an idealistic school which held that only consciousness exists, and thus was also known as Vijñānavāda (the doctrine of consciousness).

- Some scholars see the Tathāgatagarbha (or "Buddha womb/source") texts as constituting a third "school" of Indian Mahāyāna.[47]

- Vajrayāna (also known as Mantrayāna, Tantrayāna, Secret Mantra, and Tantric Buddhism) is often placed in a separate category due to its unique tantric elements.

- The Dignāga-Dharmakīrti tradition is an influential school of thought which focused on epistemology, or pramāṇa ('means of knowledge').

Many of these philosophies were brought to other regions, like Central Asia and China. After the disappearance of Buddhism from India, some of these philosophical traditions continued to develop in the Tibetan Buddhist, East Asian Buddhist and Theravada Buddhist traditions.[48][49]

Other traditions

Śramaṇic schools

Several Śramaṇic movements existed before the 6th century BCE, and these influenced most traditions of Indian philosophy.[51] The Śramaṇa ("striver," "ascetic") schools gave rise to a diverse set of beliefs. These include the acceptance or denial of the concept of atman, atomism, antinomian ethics, materialism, atheism, agnosticism, fatalism, free will, extreme asceticism, affirmation of family life, strict ahimsa (non-violence), vegetarianism and the permissibility of violence and meat-eating.[52] Notable philosophies that arose from Śramaṇic movement were Jainism, early Buddhism, Charvaka, Ajñana and Ājīvika.[53]

Ajñana philosophy

Ajñana was one of the Śramaṇa schools of Indian philosophy, which was based on a radical skepticism. It was an ascetic renouncer movement and a major rival of early Buddhism and Jainism. They have been recorded in Buddhist and Jain texts. They held that it was impossible to obtain knowledge of metaphysical nature or ascertain the truth value of philosophical propositions; and even if knowledge was possible, it was useless and disadvantageous for final salvation. They were skeptics who specialised in refutation of other doctrines, without propagating any positive doctrine of their own.

Ājīvika philosophy

The philosophy of Ājīvika was founded by Makkhali Gosala, it was another Śramaṇa rival of early Buddhism and Jainism.[54] Ājīvikas were organised renunciates who formed discrete monastic communities prone to an ascetic and simple lifestyle.[55]

Original scriptures of the Ājīvika school of philosophy may once have existed, but these are currently unavailable and probably lost. Their theories are extracted from mentions of Ajivikas in the secondary sources of ancient Indian literature, particularly those of Jainism and Buddhism which polemically criticized the Ajivikas.[56] The Ājīvika school is known for its Niyati doctrine of absolute determinism (fate), the premise that there is no free will, that everything that has happened, is happening and will happen is entirely preordained and a function of cosmic principles.[56][57] Ājīvika considered the karma doctrine as a fallacy.[58] Ājīvikas were atheists[59] and rejected the authority of the Vedas, but they believed that in every living being is an ātman – a central premise of Hinduism and Jainism.[60][61]

Charvaka and Lokāyata

Charvaka or Lokāyata was a philosophy of scepticism, hedonism and materialism, founded in the Mauryan period. They were extremely critical of other Indian religions and schools of philosophy. Charvaka deemed Vedas to be tainted by the three faults of untruth, self-contradiction, and tautology.[62] Likewise they faulted Buddhists and Jains, mocking the concept of liberation, reincarnation and accumulation of merit or demerit through karma.[63] They believed that, the viewpoint of relinquishing pleasure to avoid pain was the "reasoning of fools".[62]

Socio-Political philosophy

The Arthashastra, attributed to the Mauryan minister Chanakya, is one of the early Indian texts devoted to political philosophy. It is dated to 4th century BCE and discusses ideas of statecraft and economic policy. Other Indian texts which discuss social and political issues are the Dharmaśāstras. Dharmaśāstras like the Manusmriti are comprehensive works which discuss custom, jurisprudence, politics, royal duties, social class and caste, morality, and war.

The political philosophy most closely associated with modern India is the one of ahimsa (non-violence) and Satyagraha, popularised by Mahatma Gandhi during the Indian struggle for independence. In turn it influenced the later independence and civil rights movements, especially those led by Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela. Prabhat Ranjan Sarkar's Progressive Utilization Theory[64] is also a major socio-economic and political philosophy.[65]

Comparison of major Indian philosophies

The Indian traditions subscribed to diverse philosophies, significantly disagreeing with each other as well as orthodox Hinduism and its six schools of Hindu philosophy. The differences ranged from a belief that every individual has a soul (self, atman) to asserting that there is no soul,[66] from axiological merit in a frugal ascetic life to that of a hedonistic life, from a belief in rebirth to asserting that there is no rebirth.[67]

| Ājīvika | Buddhism | Charvaka | Jainism | Classical schools of Hinduism | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Karma | Denies[58][68] | Affirms[67] | Denies[67] | Affirms[67] | Affirms |

| Samsara, Rebirth | Affirms | Affirms[69] | Denies[70] | Affirms[67] | Some school affirm, some not[71] |

| Ascetic life | Affirms | Affirms | Denies[67] | Affirms | Affirms as Sannyasa[72] |

| Rituals, Bhakti | Affirms | Denies animal sacrifice and other Brahmanical rituals, but accepts some rituals for conventional reasons [73] | Denies | Affirms, optional[74] | Theistic school: Affirms, optional[75] Others: Deny[76][77] |

| Ahimsa and Vegetarianism | Affirms | Affirms, different schools are divided on Vegetarianism[78] | Strongest proponent of non-violence; Vegetarianism to avoid violence against animals[79] | Affirms as highest virtue, but Just War affirmed Vegetarianism encouraged, but choice left to the Hindu[80][81] | |

| Free will | Denies[57] | Affirms[82] | Affirms | Affirms | Affirms[83] |

| Varnas | Denies | Denies | Denies | Affirms | |

| Atman (Soul, Self) | Affirms | Denies[66] | Denies[84] | Affirms[85]:119 | Affirms[86] |

| Creator god | Denies | Denies | Denies | Denies | Theistic schools: Affirm[87] Others: Deny[88][89] |

| Epistemology (Pramana) | Pratyakṣa, Anumāṇa, Śabda | Pratyakṣa, Anumāṇa[90][91] | Pratyakṣa[92] | Pratyakṣa, Anumāṇa, Śabda[90] | Various, Vaisheshika (two) to Vedanta (six):[90][93] Pratyakṣa (perception), Anumāṇa (inference), Upamāṇa (comparison and analogy), Arthāpatti (postulation, derivation), Anupalabdi (non-perception, negative/cognitive proof), Śabda (Reliable testimony) |

| Textual authority | Denies | Affirms: Buddha word [94] Denies: Vedas | Denies | Jain Agamas | Affirm: Vedas and Upanishads,[note 1] Some Affirm: other texts (Agamas, Tantras) [94][96] |

| Salvation (Soteriology) | Samsdrasuddhi[97] | Nirvana and Buddhahood [98] | Denies | Siddha,[99] | Moksha, Nirvana, Kaivalya Advaita, Yoga, others: Jivanmukti[100] Dvaita, theistic: Videhamukti |

| Metaphysics (Ultimate Reality) | Depends on the school of Buddhism. For Madhyamaka it is Shunyata, for Yogacara it is consciousness, for Theravada and Vaibhasika it is a multiplicity of impermanent dharmas (phenomena). | Anekāntavāda[101] | Brahman[102][103] |

Influence

In appreciation of complexity of the Indian philosophy, T S Eliot wrote that the great philosophers of India "make most of the great European philosophers look like schoolboys".[104][105] Arthur Schopenhauer used Indian philosophy to improve upon Kantian thought. In the preface to his book The World As Will And Representation, Schopenhauer writes that one who "has also received and assimilated the sacred primitive Indian wisdom, then he is the best of all prepared to hear what I have to say to him"[106] The 19th century American philosophical movement Transcendentalism was also influenced by Indian thought[107][108]

See also

Notes

- Elisa Freschi (2012): The Vedas are not deontic authorities and may be disobeyed, but still recognized as an epistemic authority by a Hindu.[95] (Note: This differentiation between epistemic and deontic authority is true for all Indian religions.)

References

Citations

- For example, The Golden Age of Indian Buddhist Philosophy by Jan Westerhoff (2018) discusses Buddhist philosophy on its own, while Hindu Philosophy by Theos Bernard focuses on the Hindu systems.

- Roy W. Perrett (2001). Indian Philosophy: Metaphysics. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-8153-3608-2.

- Stephen H Phillips (2013). Epistemology in Classical India: The Knowledge Sources of the Nyaya School. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-51898-0.

- Arvind Sharma (1982). The Puruṣārthas: a study in Hindu axiology. Asian Studies Center, Michigan State University.;

Purusottama Bilimoria; Joseph Prabhu; Renuka M. Sharma (2007). Indian Ethics: Classical traditions and contemporary challenges. Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-3301-3. - Kathleen Kuiper (2010). The Culture of India. The Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 174–178. ISBN 978-1-61530-149-2.

- Sue Hamilton (2001). Indian Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–17, 136–140. ISBN 978-0-19-157942-4.

- John Bowker, Oxford Dictionary of World Religions, p. 259

- Wendy Doniger (2014). On Hinduism. Oxford University Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-19-936008-6.

- Andrew J. Nicholson (2013), Unifying Hinduism: Philosophy and Identity in Indian Intellectual History, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0231149877, Chapter 9

- Cowell and Gough, p. xii.

- Nicholson, pp. 158-162.

- Powers, John; Templeman, David (2012). Historical Dictionary of Tibet, Scarecrow Press, p. 566.

- Klaus K. Klostermaier (2010). Survey of Hinduism, A: Third Edition. State University of New York Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-7914-8011-3.

- Shyam Ranganathan, Hindu Philosophy, IEP

- Witzel, Michael (2003). "Vedas and Upanisads". In Flood, Gavin (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-0631215356.

- Elizabeth Reed (2001), Hindu Literature: Or the Ancient Books of India, Simon Publishers, ISBN 978-1931541039, pp. 16–19

- Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120814684, page 482

- Glucklich, Ariel (2008), The Strides of Vishnu: Hindu Culture in Historical Perspective, p. 70, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-531405-2

- Flood, op. cit., p. 231–232.

- Michaels, p. 264.

- Nicholson 2010.

- Samkhya - Hinduism Encyclopædia Britannica (2014)

- Edwin Bryant (2011, Rutgers University), The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali IEP

- Nyaya Realism, in Perceptual Experience and Concepts in Classical Indian Philosophy, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2015)

- Nyaya: Indian Philosophy Encyclopædia Britannica (2014)

- Dale Riepe (1996), Naturalistic Tradition in Indian Thought, ISBN 978-8120812932, pages 227-246

- Analytical philosophy in early modern India J Ganeri, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Oliver Leaman (2006), Shruti, in Encyclopaedia of Asian Philosophy, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415862530, page 503

- Mimamsa Encyclopædia Britannica (2014)

- JN Mohanty (2001), Explorations in Philosophy, Vol 1 (Editor: Bina Gupta), Oxford University Press, page 107-108

- Oliver Leaman (2000), Eastern Philosophy: Key Readings, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415173582, page 251;

R Prasad (2009), A Historical-developmental Study of Classical Indian Philosophy of Morals, Concept Publishing, ISBN 978-8180695957, pages 345-347 - https://books.google.co.in/books?id=OGsrAAAAIAAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=rishabhdeva+the+founder+of+jainism+archive.org&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj0-oTg2vvtAhUDSX0KHYBOB5oQ6AEwAXoECAAQAg#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Dundas 2002, pp. 30–31.

- Jay L. Garfield; William Edelglass (2011). The Oxford Handbook of World Philosophy. Oxford University Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-19-532899-8.

- Dowling, Elizabeth M.; Scarlett, W. George, eds. (2006), Encyclopedia of Religious and Spiritual Development, p. 225, Sage Publications, ISBN 0-7619-2883-9

- Dundas 2002, p. 100.

- von Glasenapp, Helmuth (1925), Jainism: An Indian Religion of Salvation [Der Jainismus: Eine Indische Erlosungsreligion], pp. 241-242. Shridhar B. Shrotri (trans.), Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass (Reprint: 1999), ISBN 978-81-208-1376-2

- Jaini, Padmanabh S. (1998) [1979], The Jaina Path of Purification, p. 91. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-1578-5

- Jaini, Padmanabh (2000). Collected Papers on Jaina Studies, pp. 31–35. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-1691-9.

- Paul Williams (2008). Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations. Routledge. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-1-134-25057-8.

- Robert Neville (2004). Jeremiah Hackett (ed.). Philosophy of Religion for a New Century: Essays in Honor of Eugene Thomas Long. Jerald Wallulis. Springer. p. 257. ISBN 978-1-4020-2073-5., Quote: "[Buddhism's ontological hypotheses] that nothing in reality has its own-being and that all phenomena reduce to the relativities of pratitya samutpada. The Buddhist ontological hypothesese deny that there is any ontologically ultimate object such a God, Brahman, the Dao, or any transcendent creative source or principle."

- Anatta Buddhism, Encyclopædia Britannica (2013)

- [a] Christmas Humphreys (2012). Exploring Buddhism. Routledge. pp. 42–43. ISBN 978-1-136-22877-3.

[b] Gombrich (2006), page 47, Quote: "(...) Buddha's teaching that beings have no soul, no abiding essence. This 'no-soul doctrine' (anatta-vada) he expounded in his second sermon." - [a] Anatta, Encyclopædia Britannica (2013), Quote: "Anatta in Buddhism, the doctrine that there is in humans no permanent, underlying soul. The concept of anatta, or anatman, is a departure from the Hindu belief in atman ("the self").";

[b] Steven Collins (1994), Religion and Practical Reason (Editors: Frank Reynolds, David Tracy), State Univ of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791422175, page 64; "Central to Buddhist soteriology is the doctrine of not-self (Pali: anattā, Sanskrit: anātman, the opposed doctrine of ātman is central to Brahmanical thought). Put very briefly, this is the [Buddhist] doctrine that human beings have no soul, no self, no unchanging essence.";

[c] John C. Plott et al (2000), Global History of Philosophy: The Axial Age, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120801585, page 63, Quote: "The Buddhist schools reject any Ātman concept. As we have already observed, this is the basic and ineradicable distinction between Hinduism and Buddhism";

[d] Katie Javanaud (2013), Is The Buddhist 'No-Self' Doctrine Compatible With Pursuing Nirvana?, Philosophy Now;

[e] David Loy (1982), Enlightenment in Buddhism and Advaita Vedanta: Are Nirvana and Moksha the Same?, International Philosophical Quarterly, Volume 23, Issue 1, pages 65-74 - Siderits, Mark. Buddhism as philosophy, 2007, p. 39

- Westerhoff, Jan. 2018. The Golden Age of Indian Buddhist Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kiyota, M. (1985). Tathāgatagarbha Thought: A Basis of Buddhist Devotionalism in East Asia. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 207–231.

- Dreyfus, Georges B. J. Recognizing Reality: Dharmakirti's Philosophy and Its Tibetan Interpretations (Suny Series in Buddhist Studies), 1997, p. 22.

- JeeLoo Liu, Tian-tai Metaphysics vs. Hua-yan Metaphysics A Comparative Study

- Balcerowicz, Piotr (2015). Early Asceticism in India: Ājīvikism and Jainism. Routledge. p. 278. ISBN 9781317538530.

- Reginald Ray (1999), Buddhist Saints in India, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195134834, pages 237-240, 247-249

- Padmanabh S Jaini (2001), Collected papers on Buddhist Studies, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120817760, pages 57-77

- AL Basham (1951), History and Doctrines of the Ajivikas - a Vanished Indian Religion, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120812048, pages 94-103

- Jeffrey D Long (2009), Jainism: An Introduction, Macmillan, ISBN 978-1845116255, page 199

- Basham 1951, pp. 145-146.

- Basham 1951, Chapter 1.

- James Lochtefeld, "Ajivika", The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Vol. 1: A–M, Rosen Publishing. ISBN 978-0823931798, page 22

- Ajivikas World Religions Project, University of Cumbria, United Kingdom

- Johannes Quack (2014), The Oxford Handbook of Atheism (Editors: Stephen Bullivant, Michael Ruse), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199644650, page 654

- Analayo (2004), Satipaṭṭhāna: The Direct Path to Realization, ISBN 978-1899579549, pages 207-208

- Basham 1951, pp. 240-261, 270-273.

- Cowell and Gough, p. 4

- Bhattacharya, Ramkrishna. Materialism in India: A Synoptic View. Retrieved 27 July 2012.

- "Sarkar, Prabhatranjan - Banglapedia". en.banglapedia.org. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- Weber, Thomas (2004). Gandhi as Disciple and Mentor. Cambridge University Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-139-45657-9.

- [a] Steven Collins (1994), Religion and Practical Reason (Editors: Frank Reynolds, David Tracy), State Univ of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791422175, page 64; "Central to Buddhist soteriology is the doctrine of not-self (Pali: anattā, Sanskrit: anātman, the opposed doctrine of ātman is central to Brahmanical thought). Put very briefly, this is the [Buddhist] doctrine that human beings have no soul, no self, no unchanging essence.";

[b]KN Jayatilleke (2010), Early Buddhist Theory of Knowledge, ISBN 978-8120806191, pages 246-249, from note 385 onwards;

[c]John C. Plott et al (2000), Global History of Philosophy: The Axial Age, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120801585, page 63, Quote: "The Buddhist schools reject any Ātman concept. As we have already observed, this is the basic and ineradicable distinction between Hinduism and Buddhism";

[d]Katie Javanaud (2013), Is The Buddhist ‘No-Self’ Doctrine Compatible With Pursuing Nirvana?, Philosophy Now;

[e]Anatta Encyclopædia Britannica, Quote:"In Buddhism, the doctrine that there is in humans no permanent, underlying substance that can be called the soul. (...) The concept of anatta, or anatman, is a departure from the Hindu belief in atman (self)." - Randall Collins (2000). The sociology of philosophies: a global theory of intellectual change. Harvard University Press. pp. 199–200. ISBN 9780674001879.

- Gananath Obeyesekere (2005), Karma and Rebirth: A Cross Cultural Study, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120826090, page 106

- Damien Keown (2013), Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction, 2nd Edition, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199663835, pages 32-46

- Haribhadrasūri (Translator: M Jain, 1989), Saddarsanasamuccaya, Asiatic Society, OCLC 255495691

- Halbfass, Wilhelm (2000), Karma und Wiedergeburt im indischen Denken, Diederichs, München, ISBN 978-3896313850

- Patrick Olivelle (2005), The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism (Editor: Flood, Gavin), Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-1405132510, pages 277-278

- Karel Werner (1995), Love Divine: Studies in Bhakti and Devotional Mysticism, Routledge, ISBN 978-0700702350, pages 45-46

- John Cort, Jains in the World : Religious Values and Ideology in India, Oxford University Press, ISBN, pages 64-68, 86-90, 100-112

- Christian Novetzke (2007), Bhakti and Its Public, International Journal of Hindu Studies, Vol. 11, No. 3, page 255-272

- [a] Knut Jacobsen (2008), Theory and Practice of Yoga : 'Essays in Honour of Gerald James Larson, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120832329, pages 15-16, 76-78;

[b] Lloyd Pflueger, Person Purity and Power in Yogasutra, in Theory and Practice of Yoga (Editor: Knut Jacobsen), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120832329, pages 38-39 - [a] Karl Potter (2008), Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies Vol. III, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120803107, pages 16-18, 220;

[b] Basant Pradhan (2014), Yoga and Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy, Springer Academic, ISBN 978-3319091044, page 13 see A.4 - U Tahtinen (1976), Ahimsa: Non-Violence in Indian Tradition, London, ISBN 978-0091233402, pages 75-78, 94-106

- U Tahtinen (1976), Ahimsa: Non-Violence in Indian Tradition, London, ISBN 978-0091233402, pages 57-62, 109-111

- U Tahtinen (1976), Ahimsa: Non-Violence in Indian Tradition, London, ISBN 978-0091233402, pages 34-43, 89-97, 109-110

- Christopher Chapple (1993), Nonviolence to Animals, Earth, and Self in Asian Traditions, State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-7914-1498-1, pages 16-17

- Karin Meyers (2013), Free Will, Agency, and Selfhood in Indian Philosophy (Editors: Matthew R. Dasti, Edwin F. Bryant), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0199922758, pages 41-61

- Howard Coward (2008), The Perfectibility of Human Nature in Eastern and Western Thought, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791473368, pages 103-114;

Harold Coward (2003), Encyclopedia of Science and Religion, Macmillan Reference, see Karma, ISBN 978-0028657042 - Ramkrishna Bhattacharya (2011), Studies on the Carvaka/Lokayata, Anthem, ISBN 978-0857284334, page 216

- Padmanabh S. Jaini (2001). Collected papers on Buddhist studies. Motilal Banarsidass Publications. ISBN 9788120817760.

- Anatta Encyclopædia Britannica, Quote:"In Buddhism, the doctrine that there is in humans no permanent, underlying substance that can be called the soul. (...) The concept of anatta, or anatman, is a departure from the Hindu belief in atman (self)."

- Oliver Leaman (2000), Eastern Philosophy: Key Readings, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415173582, page 251

- Mike Burley (2012), Classical Samkhya and Yoga - An Indian Metaphysics of Experience, Routledge, ISBN 978-0415648875, page 39

- Paul Hacker (1978), Eigentumlichkeiten dr Lehre und Terminologie Sankara: Avidya, Namarupa, Maya, Isvara, in Kleine Schriften (Editor: L. Schmithausen), Franz Steiner Verlag, Weisbaden, pages 101-109 (in German), also pages 69-99

- John A. Grimes, A Concise Dictionary of Indian Philosophy: Sanskrit Terms Defined in English, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791430675, page 238

- D Sharma (1966), Epistemological negative dialectics of Indian logic — Abhāva versus Anupalabdhi, Indo-Iranian Journal, 9(4): 291-300

- MM Kamal (1998), The Epistemology of the Carvaka Philosophy, Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies, 46(2), pages 13-16

- Eliott Deutsche (2000), in Philosophy of Religion : Indian Philosophy Vol 4 (Editor: Roy Perrett), Routledge, ISBN 978-0815336112, pages 245-248

- Christopher Bartley (2011), An Introduction to Indian Philosophy, Bloomsbury Academic, ISBN 978-1847064493, pages 46, 120

- Elisa Freschi (2012), Duty, Language and Exegesis in Prabhakara Mimamsa, BRILL, ISBN 978-9004222601, page 62

- Catherine Cornille (2009), Criteria of Discernment in Interreligious Dialogue, Wipf & Stock, ISBN 978-1606087848, pages 185-186

- AL Basham (1951), History and Doctrines of the Ajivikas - a Vanished Indian Religion, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120812048, pages 227

- Jerald Gort (1992), On Sharing Religious Experience: Possibilities of Interfaith Mutuality, Rodopi, ISBN 978-0802805058, pages 209-210

- John Cort (2010), Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195385021, pages 80, 188

- Andrew Fort (1998), Jivanmukti in Transformation, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791439043

- Christopher Key Chapple (2004), Jainism and Ecology: Nonviolence in the Web of Life, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-8120820456, page 20

- PT Raju (2006), Idealistic Thought of India, Routledge, ISBN 978-1406732627, page 426 and Conclusion chapter part XII

- Roy W Perrett (Editor, 2000), Indian Philosophy: Metaphysics, Volume 3, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0815336082, page xvii;

AC Das (1952), Brahman and Māyā in Advaita Metaphysics, Philosophy East and West, Vol. 2, No. 2, pages 144-154 - Jeffry M. Perl and Andrew P. Tuck (1985). "The Hidden Advantage of Tradition: On the Significance of T. S. Eliot's Indic Studies". Philosophy East & West. University of Hawaii Press. 35. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- Eliot, Thomas Stearns (1933). After Strange Gods: A Primer of Modern Heresy. (London: Faber). p. 40.

- Barua, Arati (2008). Schopenhauer and Indian Philosophy: A Dialogue Between India and Germany. Northern Book Centre. p. 3. ISBN 978-81-7211-243-1.

- "Transcendentalism".The Oxford Companion to American Literature. James D. Hart ed.Oxford University Press, 1995. Oxford Reference Online. Web. 24 Oct.2011

- Werner, Karel (1998). Yoga And Indian Philosophy. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 170. ISBN 978-81-208-1609-1.

Sources

- Dundas, Paul (2002) [1992], The Jains (Second ed.), Routledge, ISBN 0-415-26605-X

- Nicholson, Andrew J. (2010), Unifying Hinduism: Philosophy and Identity in Indian Intellectual History, Columbia University Press

Further reading

- Apte, Vaman Shivram (1965). The Practical Sanskrit-English Dictionary (Fourth Revised and Enlarged ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 81-208-0567-4.

- Basham, A.L. (1951). History and Doctrines of the Ājīvikas (2nd ed.). Delhi, India: Moltilal Banarsidass (Reprint: 2002). ISBN 81-208-1204-2. originally published by Luzac & Company Ltd., London, 1951.

- Balcerowicz, Piotr (2015). Early Asceticism in India: Ājīvikism and Jainism (1st ed.). Routledge. p. 368. ISBN 9781317538530.

- Cowell, E. B.; Gough, A. E. (2001). The Sarva-Darsana-Samgraha or Review of the Different Systems of Hindu Philosophy: Trubner's Oriental Series. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-24517-3.

- Flood, Gavin (1996), An Introduction to Hinduism, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-43878-0

- Gandhi, M.K. (1961). Non-Violent Resistance (Satyagraha). New York: Schocken Books.

- Jain, Dulichand (1998). Thus Spake Lord Mahavir. Chennai: Sri Ramakrishna Math. ISBN 81-7120-825-8.

- Michaels, Axel (2004). Hinduism: Past and Present. New York: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-08953-1.

- Radhakrishnan, S (1929). Indian Philosophy, Volume 1. Muirhead library of philosophy (2nd ed.). London: George Allen and Unwin Ltd.

- Radhakrishnan, S.; Moore, CA (1967). A Sourcebook in Indian Philosophy. Princeton. ISBN 0-691-01958-4.

- Stevenson, Leslie (2004). Ten theories of human nature. Oxford University Press. 4th edition.

- Hiriyanna, M. (1995). Essentials of Indian Philosophy. Motilal Banarsidas. ISBN 978-81-208-1304-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Indian philosophy. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Indian philosophy |

- A History of Indian Philosophy | HTML ebook (vol. 1) | (vol. 2) | (vol. 3) | (vol. 4) | (vol. 5) by Surendranath Dasgupta

- A recommended reading guide from the philosophy department of University College, London: London Philosophy Study Guide — Indian Philosophy

- Articles at the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Indian Psychology Institute The application of Indian Philosophy to contemporary issues in Psychology

- A History of Indian Philosophy by Surendranath Dasgupta (5 Volumes) at archive.org

- Indian Idealism by Surendranath Dasgupta at archive.org

- The Essentials of Indian Philosophy by Mysore Hiriyanna at archive.org

- Outlines of Indian Philosophy by Mysore Hiriyanna at archive.org

- Indian Philosophy by Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (2 Volumes) at archive.org

- History of Philosophy – Eastern and Western Edited by Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan (2 Volumes) at archive.org

- Indian Schools of Philosophy and Theology (Jiva Institute)

- Project Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies (Karl Harrington Potter)