Kham Magar

Kham is the name of a set of languages in the Mahakiranti sub-group of the Tibeto-Burman languages. The people call themselves both Kham and Magar while they are called Kham Magar, Western Magar, or simply Magar by outsiders. The name ‘Magar,’ may derive from the same etyma as Old Tibetan mgar-ba meaning ‘smith.’ The language was previously sometimes called "Western magar" but Kham and Magar are now known to be quite different languages. Kham communities live in the Middle Hills of mid-western Nepal, in the districts of Rukum, Rolpa, and Baglung. Scattered communities also live in Jajarkot, Dailekh, Kalikot, Achham, and Doti Districts.[1][2]

Kham language | |

|---|---|

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Kham language | |

| Religion | |

| Buddhism and Shamanism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| All aborigines groups |

Included in the Kham language group are 1) Gamale Kham (glottocode gama1251, ISO-639 kgj); 2) Eastern Parbate Kham (glot. east2354, ISO-639 kif); Western Parbate Kham (glot. west2420, ISO-639 kjl); and 4) Sheshi (Glot. shes1236, ISO-639 kil). These correspond roughly to northern, eastern, western, and southern areas of the Kham language territory.

History

Due to their oral mythology and distinctive Shamanistic practices, Kham are thought to have originally migrated from Siberia according to shamanic tradition but some writers have written that they originated in Rukum district. There is no evidence of migration or origins.

Oral histories handed down from generations to generations say that Kham people migrated from Norther icy himalayan regions which lies to the southern part of China after the Kham civilization got lost and submerged in the icy glaciers in and around 200 AD. Later on the Kham kings ruled from present Karnali region or ancient Nepal region in the far west. However, after Khas kings from Kumaon and Garwal continued to attack upon Kham kings of Humla and Jumla area in around 400 AD.

The Kham kings are reported to have fought against brute and uncivilized Khas aggressors for 100s years. But Kham's last kings were defeated when king Khudu was the king. He had fought fiercely against Garra army but could not protect his forth and was deposed. Khas kingdom flourished in the Jumla region which started their rule after which they claimed this region as Khasan.

Western Magar

Western Magar inhabit highlands 3,000–4,000 metres (9,800–13,100 ft) above sea level, some 50 km (31 mi) south of the Dhaulagiri range, forming a triple divide between the Karnali-Bheri system to the west, the Gandaki system to the east, and the smaller (west) Rapti and Babai river systems that separate the two larger systems south of this point. Since the uppermost tributaries of the Karnali and Gandaki rise beyond the highest Himalaya ranges, trade routes linking India and Tibet developed along these rivers, whereas high ridges along the Rapti's northern watershed and then the Dhaulagiri massif beyond were rigorous obstacles. Similarly, Hindu people in Hindu Muslim conflicts brahaman peoples settled out around these highlands with the western magars by following the Mahabharat Range to the south or Dhorpatan valley to the north which—by Himalayan standards—offers exceptionally easy east–west passage. The western magar highlands may also have been left as a buffer between the easternmost Baise kingdom, Salyan, and the westernmost Chaubisi kingdom, Pyuthan. For the Hindu brahaman, the intervening highlands, unsuited for rice cultivation, were hardly worth contesting.

Looking back to the historical pedigree, Kham people are considered to be existing in this Himalyan belt from the time of 3000 years ago, much longer before the birth of Buddha as they believed in shamanism, while Magars are historically mentioned after 1100 ADs by various foreign researchers.

Kham civilization is said to have given "Pal" title to many of its inhabitants. As a matter of fact, Pal kings were the early rulers of Nepal during which Kham were given the title of Pals at the end of their names. Kham people were fabricated to be Magars later on when various regimes through political upheavals initiated political titles to their Vassals and mixed and merged the ethnic titles of their subjects as per their needs.

Underdevelopment

After unification of Nepal coming Shaha king, official neglect, underdevelopment and poverty essentially continued through the 19th and 20th centuries. The main export was manpower as mercenaries to the British and Indian armies, or whatever other employment opportunities could be found for largely uneducated and unskilled labor. Western magar also practice transhumance by grazing cattle, sheep and goats in summer pastures in subalpine and alpine pastures to the north, working their way down to winter pastures in the Dang-Deukhuri valleys. Despite unending toil, food shortages have become a growing problem that still persists. Food deficits were historically addressed by grain imports bought dearly with distant work at low wages.

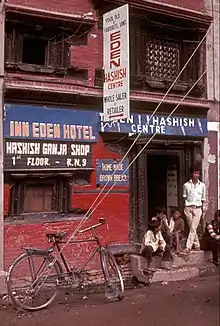

As some corrupted development brought schools, electricity, motor roads, hospitals and some range of consumer goods to specific surrounding areas, few benefits trickled up into the highlands and contrasts became even more invidious. Development introduced motor transport, which diminished porterage employment. Cultivating hemp and processing it into charas (hashish) lost standing as an income generator after 1976 when international pressure persuaded the national government to outlaw these recreational drugs and close government stores where those so inclined could freely purchase what was illegal in most of the world. But Hindu government directly indirectly encouraged the drugs.

Western magar participation in Nepalese Civil War

Despite adversity, magar people retained a robust oral history and a sense of past greatness, which created grievances and made them receptive to the Maobadi (Maoist) movement that opposed the Shah regime in the 1996-2006 Nepalese Civil War and even the multiparty democracy that the Shahs toyed with. The Rolpa and Rukum districts in the center of the magars homelands became known as the Maoist heartland and western magars were prominent as footsoldiers of its guerrilla forces.

Kham Festivals

Bhume Naach / Bal puja is one of the ancient cultural festivals celebrated by the Kham tribes of Rolpa and Rukum.

The main celebration takes place during the first week of June. Kham people dance very slowly in Jholeni and Bhume dance while Magars dance a fast dance in Kaura dance. Currently Kham people worship their ancestors through bon shamanism .

References

- Watters, David E., 1944- (2002). A Grammar of Kham. Cambridge Univ. Press.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Watters, David E., 1944- (2004). A dictionary of Kham : Taka dialect (a Tibeto-Burman language of Nepal). Kathmandu: Central Department of Linguistics, Tribhuvan University. ISBN 9993352659. OCLC 62895872.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

- "Magars in the Eyes of Western Writers: A Socio-Anthropological Review" (PDF). Govind P. Thapa, Magar Studies Center.

- Magar Studies Center

- "Sowing the Wind…: History and Dynamics of the Maoist Revolt in Nepal's Rapti Hills" (PDF). Robert Gersony for Mercy Corps International, October 2003.

- "The History and Dynamics of Nepal's Maoist Revolt" (PDF). International Resources Group, Washington, DC, IRG Discussion Forum, #15.

- "Women and Politics: Case of the Kham Magar of Western Nepal" (PDF). Augusta Molnar, American Ethnologist, 9:3 (August 1982).

- Siberian shamanistic traditions among the Kham Magars of Nepal David Watters, Contributions to Nepalese Studies, 2:1 (February, 1975), Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies (CNAS), Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu.

- John T. Hitchcock (1966) The Magars of Banyan Hill, New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- de Sales, Anne (2007). "The Kham Magar Country: Between Ethnic Claims and Maoism". In Gellner, D.N. (ed.). Resistance and the state: Nepalese experiences. Berghahn Books. pp. 326 ff. ISBN 9781845452162. Retrieved April 11, 2011.