Khas people

Khas people (Nepali: खस) also called Khas Arya[nb 1] (Nepali: खस) are an Indo-Aryan[12] ethno-linguistic group native to the Indian subcontinent, what is now present-day Nepal and Indian states of Uttarakhand (Kumaon-Garhwal), Himachal Pradesh and Jammu and Kashmir. The Khas people speak the Khas language. They are also known as Parbatiyas, Parbates and Paharis/Pahades or Gorkhali. The term Khas has now become obsolete, as the Khas people have adopted communal identities such as Bahun and Chhetri because of the negative stereotypes associated with the term Khas.[13][14][15]

खस/खसिया/पर्वते/पहाडी/गोर्खाली | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| c. 16 million[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Khas language and regional dialects (e.g. Doteli language) Nepali, Kusunda | |

| Religion | |

| Mostly Hinduism, Mastoism/khas Shamanism, Buddhism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Kumaoni people, Garhwali people, Dogra, Pahari people and Magars |

Although the term Khas has gained popularity in Nepali identity politics since the 1990s, many castes currently categorized as Khas and Arya. may not identify themselves as Khas. According to the Constitution of Nepal, western hill khas Bahuns, Chhetris, Thakuris, and Sanyasis who are citizens of Nepal should be considered as Khas Arya for electoral purposes.[16]

Origin

They have been connected to the Khasas mentioned in the ancient Hindu literature.[17] Historian Bal Krishna Sharma and Dor Bahadur Bista speculates that the Khas or kus people were of Indo-Aryan origin.[18][19] Historian Baburam Acharya speculates that Khas are a sub-clan of Aiḍa, an Arya clan originated at Idavritt (modern day Kashmir).[20][nb 2] Khas were living in the Idavaritt in the 3rd millennium BCE. and the original meaning of the term Khas was Raja or Kshatriya (Yoddha).[20] He further speculates that Kashmir has been named from its local residents Khas as Khasmir.[20] In the 2nd millennium B.C.E., one group of Khas migrated towards Iran while the other group migrated east of Sutlej river settling only in the hill regions up to Bheri River.[21] Historian Balkrishna Pokhrel contends that Khas were not the Vedic Aryans but Aryans of latter period like the Gurjara, Darada, Shaka, and Pallava.[22] He further asserts that post-Vedic Aryans were akin to Vedic Aryans in terms of Indo-Aryan languages and Indian culture.[22]

History

Khas are believed to have arrived in the western reaches of Nepal at the beginning of first-millennium B.C.[23] or middle of first-millennium A.D.[24] from the north-west. It is likely that they absorbed people from different ethnic groups during this immigration.[25] They have been connected to the medieval Khasa Malla kingdom.[17]

In the Kumaon and Garhwal regions of Uttarakhand in India, the Khas Brahmins and Khas Rajputs had a lower social status than the other Brahmins and Rajputs. However, in present-day western Nepal, they had the same status as the other Brahmins and Rajputs, possibly as a result of their political power in the Khasa Malla kingdom.[26]

Until the 19th century, the Gorkhali referred to their country as Khas Desh (Khas country).[27] As they annexed the various neighboring countries (such as Newar of the Newar people) to the Gorkha kingdom, the terms such as Khas and Newar ceased to be used as the names of countries. The 1854 legal code (Muluki Ain), promulgated by the Nepali Prime Minister Jung Bahadur Rana, himself a Khas,[28] no longer referred to Khas as a country, rather as a jāt (species or community) within the Gorkha kingdom.[29]

The Shah dynasty of the Gorkha Kingdom, as well as the succeeding Rana dynasty, spoke the Khas language (now called the Nepali language). However, they claimed to be Rajputs of western Indian origin, rather than the native Khas Kshatriyas.[30] Since outside Nepal, the Khas social status was seen as inferior to that of the Rajputs, the rulers started describing themselves as natives of the Hill country, rather than that of the Khas country. Most people, however, considered the terms Khas and Parbatiya (Pahari/Pahadi or Hill people) as synonymous.[27]

Jung Bahadur also re-labeled the Khas jāt as Chhetri in present-day Nepal.[30] Originally, the Brahmin immigrants from the plains considered the Khas as low-caste because of the latter's neglect of high-caste taboos (such as alcohol abstinence).[31] The upper-class Khas people commissioned the Bahun (Brahmin) priests to initiate them into the high-caste Chhetri order and adopted high-caste manners. Other Khas families who could not afford to (or did not care to) pay the Bahun priests also attempted to assume the Chhetri status but were not recognized as such by others. They are now called Matwali (alcohol-drinker Khas) Chhetris.[15]

Because of the adoption of the Chhetri identity, the term Khas is rapidly becoming obsolete.[13] According to Dor Bahadur Bista (1991), "the Khas have vanished from the ethnographic map of Nepal".[15]

Khas women, photographed in 1880

Khas women, photographed in 1880.jpg.webp) Mukhtiyar Bhimsen Thapa, the widely accepted first Prime Minister of Nepal

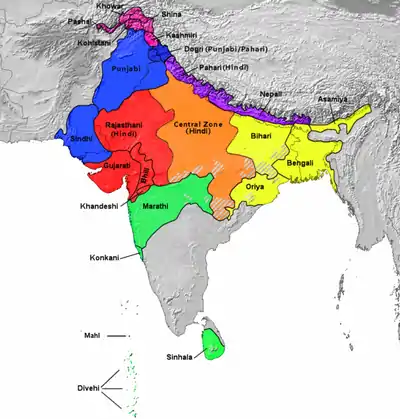

Mukhtiyar Bhimsen Thapa, the widely accepted first Prime Minister of Nepal Khas language, Belongs to the Northern Indo-Aryan language group as shown as Nepali, in purple

Khas language, Belongs to the Northern Indo-Aryan language group as shown as Nepali, in purple Khas Kingdom

Khas Kingdom

Communities

Historian Balkrishna Pokhrel writes the communities or caste in Khas group were Brahman, Chhetri, Thakuri, Sannyasi, Gharti, Damai, Kami, Sarki, Gaine, Badi, etc.[22] The tribal designation Khas refers to in some contexts only to the upper-class Khas group, i.e. Bahun and Chhetri-Thakuri, but in other contexts may also include the low status (generally untouchable) occupational Khas groups such as Kāmi (blacksmiths), Damāi (tailors), and Sārki (shoemakers and leather workers).[32] Khas people are addressed with the term Khayan or Parbatiya[22] or Partyā, Parbaté meaning hill-dweller by Newars.[32] The hill Khas tribe are in large part associated with the Gorkhali warriors.[32]

Language

History

The Khas people originally referred to their language as Khas kurā (Khas speech), which was also known as Parbatiya (the language of the hill country). The Newar people used the term Khayan Bhaya, Parbatiya[22] and Gorkhali as a name for this language, as they identified it with the Gorkhali conquerors. The Gorkhalis themselves started using this term to refer to their language at a later stage.[33] In an attempt to disassociate himself with his Khas past, the Rana monarch Jung Bahadur decreed that the term Gorkhali be used instead of Khas kurā to describe the language. Meanwhile, the British Indian administrators had started using the term Nepal (after Newar) to refer to the Gorkha kingdom. In the 1930s, the Gorkha government also adopted this term to describe their country. Subsequently, the Khas language also came to be known as Nepali language.[34] It has become a national language of Nepal and lingua franca among the majority of population of North Bengal, Sikkim and Bhutan.[22]

Classification

Historian Balkrishna Pokhrel contends that the Khas language belonged to neither the Iranian language family, nor the Indian languages, but to the mid Indo-Iranian languages.[22]

Modern

Nepal

Modern-day Khas people are referred to as Khas Brahmin (commonly called as Khas Bahun), Khas Rajput (commonly called as Khas Chhetri), and Khas Dalit.[26] Khas people are popularly referred to in modern times as Khas and Arya.

India

In Kumaon and Garhwal regions of Uttarakhand in India, too, the term Khas has become obsolete. The Khas (or Khasia(rajput from plain who marry khas women referred as khasia) people of Kumaon termed as Kumaoni Jiagahari Rajput, after being elevated to the Rajput status by the Chand kings. The term Khas is almost obsolete, and people resent being addressed as Khas because of the negative stereotypes associated with this term.[14]

Notable people

Khas Malla rulers

Other Khas

- Bir Bhadra Thapa[35]

- Sanukaji Amar Singh Thapa[35]

- Bhimsen Thapa[35]

- Jung Bahadur Rana[28]

- Kalu Pande (Kaji) [35]

- Prithvi Narayan Shah {{sfn|Pradhan|2012|p=22}

Notes

- See[2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11]

- Historian Baburam Acharya speculates that in the 3rd millennium BCE., there were two clans of Arya in the northern Indian subcontinent; Aiḍa and Mānava. Aiḍa who were named after their homeland Iḍavritt (modern day Kashmir), settled over Panjab and Ganga-Jamuna plain while Mānava settled over Awadh region. Chandravanshi kings like Bharata and Yudhisthir belonged to Aiḍa while Suryavanshi kings like Ramachandra belonged to Mānava. Later, Aiḍa built dominion over Magadh while Mānava had dominion over Videha.[20]

References

- "Nepali (npi)". Ethnologue. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- Khadka, Suman (25 Feb 2015). "Drawing caste lines". The Kathmandu Post.

- "Khas Arya quota provision in civil services opposed". thehimalayantimes.com. 10 November 2017. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "Nepal's election may at last bring stability". The Economist. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "The Kathmandu Post -PM briefs international community". kathmandupost.ekantipur.com. Retrieved 6 April 2018.

- Times, Nepali. "Quotable quota". www.nepalitimes.com. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "Next Door Nepal: Another chink in the wall". indianexpress.com. 2 April 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "Oli in balancing avatar". myrepublica.com. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "Nepal seeks unity from its first local elections in 20 years". Nikkei Asian Review. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "Lessons for India From Nepal's History of Banning Cow Slaughter - The Wire". The Wire. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "What does high caste chauvinism look like?". ekantipur.com. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Hagen & Thapa 1998, p. 114.

- William Brook Northey & C. J. Morris 1928, p. 123.

- K. S. Singh 2005, p. 851.

- Dor Bahadur Bista 1991, p. 48.

- "Part-8 Federal Legislature – Nepal Law Commission". Retrieved 2019-08-05.

- John T Hitchcock 1978, pp. 112-119.

- Sharma 1999, p. 181.

- Dor Bahadur Bista 1991, p. 47.

- Acharya 1975, p. 199.

- Acharya 1975, p. 200.

- Pokhrel 1973, p. 229.

- Dor Bahadur Bista 1991, p. 15.

- Sharma 1999, p. 112.

- John T Hitchcock 1978, p. 113.

- John T Hitchcock 1978, pp. 116-119.

- Richard Burghart 1984, p. 107.

- Dor Bahadur Bista 1991, p. 37.

- Richard Burghart 1984, p. 117.

- Richard Burghart 1984, p. 119.

- Susan Thieme 2006, p. 83.

- Whelpton 2005, p. 31.

- Richard Burghart 1984, p. 118.

- Richard Burghart 1984, pp. 118-119.

- Pradhan 2012, p. 22.

Bibliography

- Acharya, Baburam (1975), Bhandari, Devi Prasad (ed.), "Itihas Kaalbhanda Pahile" (PDF), Purnima, Kathmandu, 8 (1)

- Dor Bahadur Bista (1991). Fatalism and Development: Nepal's Struggle for Modernization. Orient Blackswan. ISBN 978-81-250-0188-1.

- John T Hitchcock (1978). "An Additional Perspective on the Nepali Caste System". In James F. Fisher (ed.). Himalayan Anthropology: The Indo-Tibetan Interface. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-90-279-7700-7.

- Toni Hagen; Deepak Thapa (1998). Toni Hagen's Nepal: The Kingdom in the Himalaya. Himal Books.

- K. S. Singh (2005). People of India: Uttar Pradesh. Anthropological Survey of India. ISBN 978-81-7304-114-3.

- Pokharel, Balkrishna (December 1, 1973) [1962], "Ancient Khas Culture" (PDF), Regmi Research Series, 5 (12): 229–236

- Pradhan, Kumar L. (2012), Thapa Politics in Nepal: With Special Reference to Bhim Sen Thapa, 1806–1839, New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company, p. 278, ISBN 9788180698132

- Richard Burghart (1984). "The Formation of the Concept of Nation-State in Nepal". The Journal of Asian Studies. 44 (1): 101–125. doi:10.2307/2056748. JSTOR 2056748.

- Susan Thieme (2006). Social Networks and Migration: Far West Nepalese Labour Migrants in Delhi. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 978-3-8258-9246-3.

- William Brook Northey; C. J. Morris (1928). The Gurkhas: Their Manners, Customs, and Country. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 978-81-206-1577-9.

- Whelpton, John (2005). A History of Nepal. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521804707.

- Sharma, Bal Krishna (1999). The origin of caste system in Hinduism and its relevance in the present context. Indian Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge and Samdan Publishers. ISBN 9788172144968.

- Adhikary, Surya Mani (1997). The Khaśa kingdom: a trans-Himalayan empire of the middle age. Nirala. ISBN 978-81-85693-50-7.

- D.R. Regmi (1965), Medieval Nepal, 1, Firma K.L. Mukhopadhyay

- Thakur, Laxman S. (1990). K. K. Kusuman (ed.). The Khasas An Early Indian Tribe. A Panorama of Indian Culture: Professor A. Sreedhara Menon Felicitation Volume. Mittal Publications. pp. 285–293. ISBN 978-81-7099-214-1.

- Tucci, Giuseppe (1956), Preliminary Report on Two Scientific Expeditions in Nepal, David Brown Book Company, ISBN 9788857526843