King's Regiment (Liverpool)

The King's Regiment (Liverpool) was one of the oldest line infantry regiments of the British Army, having been formed in 1685 and numbered as the 8th (The King's) Regiment of Foot in 1751. Unlike most British Army infantry regiments, which were associated with a county, the King's represented the city of Liverpool, one of only four regiments affiliated to a city in the British Army.[lower-alpha 2] After 273 years of continuous existence, the regiment was amalgamated with the Manchester Regiment in 1958 to form the King's Regiment (Liverpool and Manchester), which was later amalgamated with the King's Own Royal Border Regiment and the Queen's Lancashire Regiment to form the present Duke of Lancaster's Regiment (King's, Lancashire and Border).

| King's (Liverpool Regiment) King's Regiment (Liverpool)[lower-alpha 1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Active | 1 July 1881 – 1 September 1958 |

| Country | |

| Branch | |

| Type | Line infantry |

| Size | Varied; see full list of battalions |

| Regimental Depot | Warrington (1881–1910) Seaforth (1910–1958) |

| Nickname(s) | The Leather Hats, The King's Hanoverian White Horse |

| Motto(s) | Nec Aspera Terrent (Difficulties be Damned) |

| Colours | Blue |

| March | Quick March: Here's to the Maiden Slow March The English Rose,[1] |

| Anniversaries | Somme (1 July) Blenheim (13 August) Delhi (14 September) |

| Engagements | World War I Russian Civil War Anglo-Irish War World War II |

| Commanders | |

| Colonel-in-Chief | King George V (c. 1925–1936) |

| Colonel of the Regiment | Brigadier Richard Nicholas Murray Jones (1957–1958) |

The King's notably saw active service in the Second Boer War, the two world wars, and the Korean War. In the First World War, the regiment contributed dozens of battalions to the Western Front, Salonika, and the North West Frontier. More than 13,000 men were killed. In the Second World War, the 5th and 8th (Irish) battalions landed during Operation Overlord, the 1st and 13th fought as Chindits in the Burma Campaign, and the 2nd Battalion served in Italy and Greece. The King's later fought in the Korean War, earning the regiment's last battle honour.

Nine Victoria Crosses were awarded to men of the regiment, the first in 1900 and the last in 1918. An additional two were awarded to Royal Army Medical Corps officer Noel Godfrey Chavasse, who was attached to the 10th (Scottish) Battalion during the Great War.

In peacetime, the regiment's battalions were based in the United Kingdom and colonies in the British Empire. Duties varied: riots were suppressed in Belfast, England, and the Middle East; bases were garrisoned in places such as the North-West Frontier Province and West Germany; and reviews and parades conducted throughout the regiment's history.

Colonial wars (1881–1914)

The Cardwell–Childers reforms from the 1860s to the 1880s substantially reorganised the British Army,[2] principally by amalgamating single-battalion regiments to form regiments of multiple battalions.[2][3] The King's, which already had two regular battalions, did not amalgamate, but did adopt a new title on the numbering system's abolition.[4] Thus, on 1 July 1881, the two battalions of the 8th (The King's) Regiment of Foot became the 1st and 2nd Battalions, The King's (Liverpool) Regiment.[5] The 8th Foot had been associated with Liverpool since 1873, when it became allocated to the town's 13th Brigade Depot.[6] Regular regiments gained auxiliary battalions through the integration of the militia and volunteers, of which nine from Lancashire and the Isle of Man transferred to the King's and ultimately became part of the Special Reserve and Territorial Force.[4][7]

The battalions after the 1881 reforms included:[8][9]

Regulars

- 1st Battalion

- 2nd Btn

Militia

- 3rd (Militia) Btn , former 1st Btn, 2nd Royal Lancashire Militia (The Duke of Lancaster's Own Rifles)

- 4th (Militia) Btn , former 2nd Btn, 2nd Royal Lancaster Militia (The Duke of Lancaster's Own Rifles)

Rifle Volunteers

- [5th] 1st Lancashire Rifle Volunteer Corps, became 1st Volunteer Btn in 1888

- [6th/7th] 5th Lancashire (The Liverpool Rifle Volunteer Brigade) Rifle Volunteer Corps acting as a double battalion, became 2nd and 3rd Volunteer Btns in 1888

- [8th] 15th Lancashire Rifle Volunteer Corps, became 4th Volunteer Btn in 1888

- [9th] 18th (Liverpool Irish) Rifle Volunteer Corps (also including the Isle of Man RVC), became 5th (Irish) Volunteer Btn in 1888

- [10th] 19th (Liverpool Press Guard) Lancashire Rifle Volunteers, became 6th Volunteer Btn in 1888

Under the new system, it was envisaged that one regular battalion would be based in the United Kingdom and one overseas.[2] The 1st Battalion had been in North West England since the late 1870s and had been bombed while based at Salford Barracks in 1881.[4] The attack had been the first in a dynamite campaign instigated by the Irish Republican Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa.[10] The barracks sustained only minor structural damage from the explosion, which killed a child and badly wounded its mother.[4] Soon afterwards, rioting during mineworkers' strikes in Chowbent, Wigan, and Warrington required the battalion's intervention to prevent further disorder.[11] In 1882, the battalion moved to Ireland, based in the Curragh. During the otherwise uneventful posting, the 1st responded to riots in Belfast. The sectarian disorder coincided with the introduction of the 1886 Home Rule Bill in the British Parliament. The battalion returned to England three years later.[12]

%252C_1891.jpg.webp)

The 2nd King's had been on the Indian subcontinent since 1877 and had fought in the Second Afghan War. The Third Burmese War punctuated the battalion's overseas service in the 1880s.[4] Intent on deposing Upper Burma's King Thibaw and imposing imperial rule, Britain issued an ultimatum consisting of demands that were rejected as anticipated.[13] The invasion began in November 1885 in the form of the Burma Field Force, which progressed up the Irrawaddy River via transports, enabling the rapid capture of frontier forts and the capital Mandalay. After the capital's seizure, the battalion provided an escort that oversaw the exile of Thibaw.[4] A guerrilla campaign against the British followed the completion of Upper Burma's annexation on 1 January 1886, lasting for at least five years.[13] For more than a year, the King's operated in small groups pursuing guerrillas in the Burmese jungle. Casualties numbered 12 officers and 256 men by the time the battalion had returned to India.[4] In early 1900 the 2nd Battalion Liverpool Regiment was stationed at Gibraltar.[14]

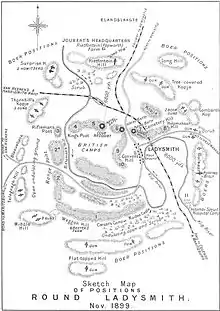

Overseas service for the 1st King's included a two-year residence in Nova Scotia, beginning in 1893.[15] In January 1895, the battalion provided a 100-man guard of honour when the body of Canadian Prime Minister John Thompson was returned from Britain.[16] The battalion subsequently became stationed in the West Indies, then Cape Colony in 1897. The Second Boer War began two years later.[17] Prior to the outbreak of the war, as the discord between the British and Boer republics escalated, the 1st King's formed a company of mounted infantry and underwent intensive training at Ladysmith, Natal Colony.[17] War was declared on 11 October and Natal invaded by a Boer force under General Piet Joubert. General George White held authority over 13,000 British personnel dispersed throughout Natal.[18] Heavy losses were incurred by the British in the first major engagements of the war, at Talana Hill and Elandslaagte. Retreat to Ladysmith, where the British concentrated its largest contingent, ensued.[19] Having besieged Kimberley and Mafikeng, Boers converged upon Ladysmith and positioned artillery pieces on surrounding hills overlooking the town.[20]

On 30 October, General White ordered an attack on northern Boer positions. White's plans were described as vague, ambitious, and complicated, and the battle proved a disaster that became known to the British as "Mournful Monday".[21][22][23] The 1st King's were allocated to Colonel Grimwood's column, which intended to advance on and secure Long Hill, believed to constitute the Boer's left flank. Unbeknownst to Grimwood, almost half of the brigade separated from the column during the night march while following a rightward deviation by the artillery batteries,[24] including the oblivious 1st King's and Royal Dublin Fusiliers.[25] In the morning light, the brigade discovered that its right flank was exposed by the distance of John French's cavalry and that Long Hill was unoccupied.[24] Grimwood and French's men became pinned down by heavy rifle and artillery fire.[23] Amidst rumours of an attack against the town being imminent and failure evident, White ordered the column to retreat at noon.[23][24] The artillery provided cover during the chaos that followed and prevented greater loss of life.[23] At Nicholson's Nek, to the north-west of Long Hill, the Boers took more than 1,000 prisoner.[26]

The Boers enclosed Ladysmith on 2 November, beginning a 118-day siege. The King's, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Llewelyn Mellor, became assigned to the north-eastern defensive sector under Colonel Knox, a disciplinarian who instituted a programme of fortification development in his area.[27][28] Construction of the defences occurred mostly at night, although rain, oppressive heat, and cold limited the opportunity to rest.[28] On 6 January, the King's mounted infantry helped repulse a Boer attempt to penetrate the southern perimeter. By late January, the scarcity of supplies had become particularly acute. Disease pervaded while the town resorted to consuming the garrison's horses and mules.[29]

Reinforcements began to arrive in South Africa in November under General Redvers Buller. The relief of the three besieged garrisons became the general's priority. He divided his corps and assumed personal command of the Ladysmith expedition.[30] The relief effort was hindered by three successive defeats in December, termed by the British as "Black Week", and further reverses in January and early February. The siege of Ladysmith ended on 28 February. The King's then gained a volunteer company and had its mounted infantry absorbed by an MI battalion.[31]

| External image | |

|---|---|

Britain eventually extended its prosecution of the war into the Orange Free State and Transvaal Republic. On 21 August, at Van Wyk's Vlei, Sergeant Hampton and Corporal Knight held their positions and evacuated wounded mounted Kingsmen under heavy fire, for which they received the Victoria Cross. Two days later, Boer forces attacked the 1st Battalion while it was at the forefront of an advance south of Dalmanutha. The protracted engagement ended when the King's were ordered to withdraw, having almost expended their ammunition.[32] Casualties exceeded 70, while Private Heaton earned the Victoria Cross.[33]

The nominal annexation of the Orange Free State and Transvaal Republic in May and September did not resolve the war. Instead, the Boer commandos transitioned to guerrilla warfare and resisted the British until 1902. The King's concentrated in the Eastern Transvaal, where Boers under Botha and Viljoen operated. Detachments occupied networks of blockhouses and provided complements for armoured trains.[34] One such detachment was overwhelmed at Helvetia on 29 December. Situated near the Lydenburg–Machadodorp railway, Helvetia was garrisoned primarily by a contingent of the King's equipped with a 4.7-in gun nicknamed "Lady Roberts". The nocturnal attack, conducted in fog, yielded considerable success for the Boers with scores of prisoners taken and the gun captured. Only King's Kopje withstood the attack.[35] The circumstances were controversial and a general court-martial later sentenced Major Stapleton Cotton, who ordered the surrender, to be cashiered and dismissed from the army. Author Arthur Conan Doyle publicly questioned the decision and contended that the wounds Major Cotton sustained merited "some revision" of the officer's sentence.[36][37]

With the continuation of the war in South Africa, a number of regiments containing large centres of population formed additional regular battalions. The King's (Liverpool Regiment) formed 3rd and 4th regular Battalions in February 1900,[38] when the militia battalions were relabeled as the 5th and 6th battalions. The Boer War also provided the first opportunity for the regiment's volunteer battalions to serve overseas with regular forces, supplying individual detachments and service companies. The militia battalions, numbered the 5th and 6th during the war, contrastingly deployed to South Africa intact late in the conflict. A memorial sculpted by William Goscombe John to commemorate the regiment's service in Afghanistan, Burma, and South Africa was erected in St John's Gardens, Liverpool and unveiled by Field Marshal Sir George White on 9 September 1905.[39]

Following the end of the war in South Africa, the 2nd battalion was in September 1902 stationed in Limerick.[40] The 1st battalion was stationed in Rangoon from late November the same year, with a company posted to the Andaman Islands.[41][42]

In 1908, the Volunteers and Militia were reorganised nationally, with the former becoming the Territorial Force and the latter the Special Reserve;[43] the regiment now had two Reserve and six Territorial battalions.[lower-alpha 3]

First World War

1914–1915

The regiment fielded at least 49 battalions during the First World War, from a pre-war establishment of two regular, two militia, and six territorial.[45] Of those battalions, 26 served abroad,[45][46] receiving 58 battle honours and six Victoria Crosses for service on the Western Front, the Balkans, India, and Russia. Some 13,795 Kingsmen died during the course of the war, the battalions suffering an average of 615 deaths.[47] Thousands more would be wounded, sick, or taken prisoner. Of specific formations, the four Liverpool Pals battalions had nearly 2,800 casualties, while the 55th (West Lancashire) Division's 165th (Liverpool) Brigade, composed entirely of battalions from the King's, incurred 1,672 dead, 6,056 wounded, and 953 missing during the period of 3 January 1916 and 11 November 1918.[48]

_Britons_(Kitchener)_wants_you_(Briten_Kitchener_braucht_Euch)._1914_(Nachdruck)%252C_74_x_50_cm._(Slg.Nr._552).jpg.webp)

A vigorous recruiting campaign involving pre-war personalities such as Lord Kitchener and Lord Derby facilitated the rapid expansion of the British Army. Territorial units formed duplicate battalions from August 1914 to May 1915. To differentiate them, they were, for instance, designated the 2/5th and 3/5th battalions, respectively. Second-line battalions had been raised for home service and recruit training, but were ultimately dispatched to the Western Front and replaced by the third-line.[49] Driven by a conviction that the war would not be resolved quickly and seeking an alternative to the Territorial Army, Secretary of State for War Lord Kitchener appealed for an initial 100,000 volunteers to form a "New Army".[50][51] The 17th Earl of Derby proposed forming a battalion of "Pals" for the King's Regiment, to be recruited from men of the same workplace. His proposal proved successful. Within a week, thousands of Liverpudlians had volunteered for service, to eventually be formed into the 17th, 18th, 19th, and 20th Battalions. Collectively, the battalions became known as the City of Liverpool battalions or "Liverpool Pals". Lord Derby addressed recruits on 28 August:

This should be a battalion of Pals, a battalion in which friends from the same office will fight shoulder to shoulder for the honour of Britain and the credit of Liverpool.[52]

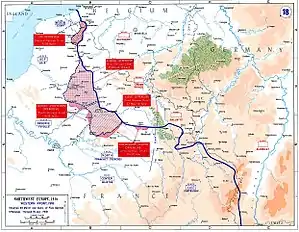

Mobilisation began at the onset of the war, in August 1914, at which time the 1st King's was based at Aldershot. Under command of Lieutenant-Colonel W.S. Bannatyne, the 1st King's boarded the SS Irrawaddy at Southampton.[53] The battalion landed at Le Havre on 13 August with the 6th Brigade, 2nd Division, one of the original components of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF). The BEF first engaged the German Army at Mons, Belgium, after which it went into a retreat that was sustained until 5 September, when the Allies resolved to stand at the Marne, a river east of Paris. Having acted as a rearguard to the 2nd Division, the 1st King's and its brigade prevented a German force cutting off the 4th (Guards) Brigade, forming the rearguard at Villers-Cotteréts, and 70th Battery, Royal Field Artillery. The brigade extricated the guns, earning it praise from the 2nd Division's commanding officer, Major-General Monro.[54]

The Allies halted the German advance in the First Battle of the Marne; the ensuing retreat, which prompted an Allied counter-offensive, ended at the Aisne. After both battles had been fought, the battalion moved north to Ypres, during the so-called "Race to the Sea". In an action at Langemarck during the First Battle of Ypres, the battalion captured the small village of Molenaarelstoek, just north-east of Polygon Wood. As the battle progressed, the German command sought a decisive victory against the outnumbered BEF and launched First Ypres' last major assault on 11 November.[55][56]

Located to the south of Polygon Wood, the 1st King's was one of only a few units available to defend British lines. A force of "12 and a half" divisions, including a composite of the élite Prussian Guard, attacked at 0900 along a 9 miles (14 km) front extending from Messines to Polygon.[57] Some German units breached the front in places but quickly lost momentum and were gradually pushed back by a desperate defence.[58] The Prussian Guard had advanced in dense formations, each guardsman effectively side by side and led by sword-wielding officers.[59] In the defence of Polygon Wood, the 1st King's held on and virtually destroyed the 3rd Prussian Foot Guards with concentrated rapid-fire and artillery support.[58][60] By battle's end, the 1st King's casualties numbered 33 officers and 814 other ranks from an original strength of 27 officers and 991 other ranks.[61] Among the battalion's dead was Lieutenant-Colonel Bannatyne, killed by a sniper on 24 October.[62]

By the end of March 1915, the King's had eight battalions on the Western Front. The 1st and 1/5th participated in a "holding" attack at Givenchy designed to support the Allied offensive at Neuve Chapelle.[63] An ineffectual preliminary bombardment failed to destroy much of the barbed wire, fatally impeding the 1st King's.[64] The withering hail-of-fire inflicted heavy casualties on the King's, one of whom was the wounded Lieutenant-Colonel Carter.[65] A platoon under Lieutenant Miller managed to reach German lines and blockade itself in a communications trench for over an hour, under fire from Allied artillery, until withdrawing to British lines.[65] The battalion's casualties amounted to 61 killed, 115 wounded, and 62 missing.[65]

One-month later, on 24 April, a German offensive began Second Ypres, which became the 4th and 1/6th King's first major battle. In the second subsidiary action of the offensive, at Saint-Julien, the 4th King's sustained more than 400 casualties over a four-day period, the majority, some 374, while supporting the 1/4th Gurkha Rifles on the 27th.[66] The 1/6th supported 1st Cheshires in the defence of Hill 60. After the regiment's involvement in 'Second Ypres' receded, four battalions fought at Festubert, collectively incurring in excess of 1,200 casualties. Lance Corporal Tombs became the regiment's first Victoria Cross recipient of the war for assisting wounded soldiers during the battle. The 1/10th Battalion fought its first battle on 16 June, in a "local" action at Bellewaarde. Losses for the Liverpool Scottish neared 400 killed, wounded and missing, with just two of 24 officers present surviving unscathed.[67]

The British instigated a new offensive on 25 September, at Loos, to coincide with French offensives in the Champagne and Artois regions.[68] The King's were represented in the offensive by eight battalions, from standard infantry to pioneers. Some 150 tons of Chlorine gas was used on the first day of the battle, discharged via thousands of cylinders.[69] Strong winds blew the gas backwards, hindering the advance of the 1st King's and other units having to also contend with partially uncut barbed wire. The advance of the 1/9th King's also stalled, though they took about 300 Germans prisoner.[70] The battalion later assisted in the repulse of a German counter-attack on 8 October. More battalions arrived before the year ended, including the 17th, 18th, 19th, and 20th Liverpool Pals, which formed the 89th Brigade, 30th Division.[71]

1916–1917

.jpg.webp)

The Liverpool Pals' first battle came during "The Big Push" on 1 July 1916, on the first day of the Battle of the Somme, the worst single day for casualties in British military history. The 89th Brigade, under the Earl of Derby's brother Brigadier F.C. Stanley,[73] still comprised the 17th, 19th, and 20th Pals, but had the 18th reassigned to the 21st Brigade in December.[74] The 30th Division formed part of XIII Corps, which attacked towards Montauban, south of where Britain suffered the majority of its nearly 60,000 casualties on the 1st. At 07:30, the 30th Division began its advance on the left of the French Corps de Fer. Meeting limited opposition, the Pals completed their objectives with comparatively minimal casualties. Grievous losses were, however, incurred by the 18th from heavy machine-gun fire during its advance towards the Glatz Redoubt. The battalion's commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel E.H. Trotter, killed by a shell on 8 July, intentionally underestimated the battalion's casualties of about 500 to avoid the deployment of brigade reserves.[75]

More battalions entered the fray throughout the offensive. Some 14 battalions contributed to five attempts to capture the village of Guillemont between July and September.[76] In the early hours of 8 August, in the third attempt, the 1st, 1/5th, and 1/8th attacked in conditions that rendered visibility poor.[77] The 1st and 1/8th reached the German front-line trenches and entered the village.[77] Their situation deteriorated, however, and the 1/8th's support battalion was driven back by Germans who continued to occupy the first-line trenches. Isolated and contained by counter-attacks, the 1/8th and three companies of the 1st were surrounded and mostly captured.[77] The 1/8th had been annihilated, with losses amounting to 15 killed, 55 wounded, and 502 missing, while the 1st lost its commanding officer, Colonel Goff, and sustained 239 casualties.[77] The 1st later received a draft of 20 officers and 750 men from the Manchester Regiment.[78]

Wanting to alleviate the pressure on the French to the south and believing there might still be some holding out,[79] high command ordered the 2nd and 55th divisions to resume the battle on the 9th.[77] The attack failed and proved to be ill-prepared and disorganised, with an identical starting time and objectives. For his actions during the battle, Captain Chavasse, attached to the Liverpool Scottish, gained the first of two VCs for attending to and rescuing wounded in no man's land.[79] The village would not be captured until the final struggle began on 3 September, by which time the 12th was the King's only contribution,[80] and the regiment had more than 3,000 casualties.[81]

After the Somme Offensive ended in November, the Allies began to prepare for a series of combined Allied offensives in April 1917. These plans would not be significantly disrupted by the German Army's strategic withdrawal to the "Hindenburg Line" in northern France.[82] The phased withdrawal, conducted from February to April, reduced the German front by 25 miles (40 km).[82] The regiment's six second-line battalions arrived on the Western Front with the 57th (2nd West Lancashire) Division in February 1917.[83]

To support the ill-fated Nivelle Offensive, Britain initiated the Battle of the Scarpe, in the Arras area on 9 April, which involved the regiment's 11th, 13th, and Liverpool Pals battalions.[84] The 13th moved forward with the 3rd Division at 0530, near Tilloy-les-Mofflaines, capturing almost 500 men and completing its objectives. To the south, barbed wire obstructed the Pals with varied results. The 18th consolidated in front of the wire until relieved on the 10th, while the 19th and 20th were eventually withdrawn, having suffered heavy losses within about 100 yards (91 m) of the wire.[85][86] Casualties for the King's during the initial phase of the Arras Offensive exceeded 700.[85]

While the battle raged in Arras, the Allies prepared for an offensive in the north, in Flanders. "Third Ypres" (or Passchendaele) became notorious for conditions that transformed the terrain of shell holes and trenches into a quagmire of mud.[87][88] Ten of the regiment's battalions were active in the first stage, the Battle of Pilkem Ridge (31 July – 2 August). Six belonged to the 55th Division, situated in the Wieltje sector, north of the Liverpool Pals. The territorial battalions overcame their first and second objectives, but progress was difficult.[89] Confusion prevailed during the 18th King's and 2nd Wiltshires nocturnal advance through Sanctuary Wood.[90][91] The Pals battalions had to consolidate in front of the 30th Division's initial objective.[92] The King's losses accumulated, surpassing 1,800 by the 3rd, with the supporting 1/8th's casualties the heaviest at 18 officers and 304 other ranks.[93] The 10th's medical officer, Captain Chavasse, received a posthumous, second Victoria Cross for attending to, and recovering, wounded in spite of his own wounds and fatigue during the battle.[89] He succumbed to his wounds on 4 August.[94]

An account by Captain Wurtzburg, 2/6th Liverpool Rifles, described the conditions endured by soldiers in the Ypres area:

...Those who took part in it will never erase from their minds its many ghastly features, among which the mud and the multitude of dead will stand out pre-eminent. Of the former it must be said that the sodden condition of the ground, though it stopped our advance, certainly prevented many casualties from shell-fire, but at the same time many a wounded man was sucked down into the horrible quagmire and stretcher-bearers found their task in many cases beyond their powers.[95]

1918

The King's contributed to the Battle of Cambrai in November 1917 and assisted in defensive actions as the new year neared.[96] Acute manpower shortages in the BEF on the Western Front left many divisions understrength and so it was decided to adopt a nine-battalion system through amalgamations and disbandments.[97] The 5th, 8th, 9th, and 10th King's integrated with their second-line, while hundreds of their men were distributed to other King's battalions.[98] The 20th disbanded in February, with its strength dispersed to the other Liverpool Pals.[99]

As the American Expeditionary Forces emboldened the Allies, Germany prepared for a final attempt to achieve a decisive victory before the US contingent on the Western Front surged further.[100] On 21 March, a five-hour artillery and gas shell barrage across a 50-mile (80 km) front signified the beginning of the Battle of St. Quentin (Operation Michael) and the Spring Offensive in the Somme.[101] Although roled as pioneers, the 11th King's occupied frontline trenches near Urvillers when the attack began.[102] Two of its companies engaged troops at Lambay Wood and Benay and the battalion's casualties for the day exceeded 160.[103] The Liverpool Pals, in reserve on the 21st, hurried to the front on the 22nd to undertake localised counter-attacks, with the first and largest conducted by the 19th against the village of Roupy.[104] The battalion advanced in darkness after 0115, uncertain of German positions, but retook the original frontline trenches unopposed. They later came under sustained attack, holding out without support until Lieutenant-Colonel Peck ordered a withdrawal at about 1600. The Germans overwhelmed the survivors, capturing the wounded Peck and many others.[105]

The situation became dire, forcing troops to withdraw towards Ham, which itself had to be evacuated.[104] The Third and Fifth Armies went into retreat.[106] The 1st King's, occupying positions near Vélu Wood during the Battle of Bapaume, came under attack on the 24th but held out until their deteriorating flanks compelled a retreat that was covered by about 30 men from its headquarters. The battalion commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Murray-Lyon, had just 60 men at his command when they arrived at Beaulencourt later in the day.[107] On 28 March, the offensive was extended to Arras, which was soon repulsed by the Allies.[106] Having lost its momentum and suffered about 250,000 casualties, comparable to Allied losses, Germany abandoned the operation on 5 April.[108] The German Army did not relent and launched Operation Georgette in Flanders on 9 April. The first-day of the Battle of the Lys involved the three King's battalions of the 165th Brigade, situated at Estaires. The bombardment against Allied positions began at 0410 and the subsequent infantry attack displaced Portuguese forces by 0800, exposing the left flank of the 165th. The King's repulsed the frontal assaults with heavy casualties but continued to be attacked from the flanks. Counter-attacks by the 1/7th King's and 2/5th Lancashire Fusiliers took up to 500 prisoners.[109]

German forces made significant gains, capturing Armentières. On 11 April, British Commander-in-Chief, General Haig, issued his "backs to the walls" order of the day.[108] Five days later, Private Counter, 1st King's, volunteered as a messenger, having witnessed five preceding runners killed. He was awarded the regiment's last Victoria Cross.[110] The 4th King's experienced heavy fighting near Méteren and by 19 April had at least 489 casualties.[111] Despite relentless battles, the Allies stabilised their front and Georgette was discontinued on 29 April after the Battle of the Scherpenberg. The Liverpool Pals fought in that climax, with the 17th having to withdraw with the loss of "A" Company, while the 18th and 19th repelled their attackers.[112][113]

The German Army halted its offensives in July. The King's 11th Battalion disbanded in April, followed in May by the temporary consolidation of the Liverpool Pals as the 17th (Composite) Battalion. Their brief unity ended in May when they reduced to form training cadres for the U.S. 137th Regiment.[114] In August, after four months of being on the defensive, the Allies launched an offensive against Amiens, in the Somme area. Meticulous preparation gave them the element of surprise when it began on the 8th. More than 16,000 prisoners were taken within two hours and the German frontline mostly collapsed.[115] In the following Battle of Albert, begun on the 21st, the 13th King's suffered 274 casualties, but captured 150 soldiers and many machine-guns, while the 1st assisted in the taking of Ervillers.[116]

The war's end in Europe came with the signing of the Armistice of 11 November 1918. The 9th Battalion's history illustrated the initial reaction of soldiers:

While on parade on the morning of the 11th November it was announced to the men that the Armistice had been signed. The news of the cessation of hostilities was received by the soldiers without any manifestation of the joy or excitement that marked the occasion at home. The parade continued and the rest of the day was spent quite as usual. The news for which the men had waited so long seemed when it came to be almost too good to be true.[117]

On 11 December 1918, the remnants of the 1st King's marched across the German frontier "at ease", bayonets fixed and their colours uncased.[118] The battalion would be based at Düren and Berg Neukirchen for about five months as part of the British Army of the Rhine, joined by other battalions such as the 13th. Some, including the 25th (Reserve), served in Egypt and Belgium before the majority disbanded by late 1919.[118]

Inter-war (1918–1939)

Hostilities did not end for the 17th King's on 11 November; the battalion had sailed for Murmansk, Russia, in October as part of an Allied intervention force assembled to support the "White" forces in their civil war against the Bolsheviks. The battalion was moved to Archangel, where it was based intact for a short period. The battalion's companies served separately for the duration of their stay in Russia, until the 17th left in September 1919.[119]

The Territorial Force was disbanded and later reformed as the Territorial Army and the regiment's battalions were also reformed. However, inter-war reductions and reorganisations reduced the regiment's territorial battalions from six to just one by 1937. The 8th disbanded in the early 1920s, the 9th was absorbed by the Royal Engineers, and a restructuring of the Territorial Army's infantry in the mid-1930s converted the 6th, 7th, and 10th to new roles.[120][121] The 6th were transferred to the Royal Engineers and became 38th (King's) Searchlight Regiment, Royal Engineers. The 7th joined the Royal Tank Regiment and became the 40th (The King's) Royal Tank Regiment, and the 10th became a battalion of the Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders.[122]

1st King's

As Britain's control of Ireland eroded in 1920 during the Irish War of Independence, the 1st Battalion deployed to Bantry, County Cork. The county was a ferment of Republican activity where British forces frequently subjected the movement's supporters to oppressive measures in an attempt to curtail escalating violence.[123] Compared to other regiments operating in the county, such as the Essex Regiment, the King's acquired a favourable reputation among its adversaries for their professionalism and humane treatment of prisoners—which reputedly saved the lives of some Kingsmen.[124] Their conduct was described by Tom Barry, a prominent IRA leader, as "exemplary in all the circumstances".[124] After the establishment of the Irish Free State in the south, the battalion moved to Northern Ireland to be stationed in Derry and Omagh.[123]

After a brief deployment to Turkey as part of the army of occupation, the battalion returned to England in 1924 and resumed overseas service in 1926 with postings to Malta, Sudan, and Egypt. While much of the battalion's time in Egypt was peaceful and comfortable, they occasionally dealt with rioting, and on one occasion a company had to be deployed to Jerusalem.[125] In an uprising during October 1931, Greek Cypriots in Cyprus demanded union with Greece. The battalion reinforced the British garrison with two companies; C Company arrived via eight Vickers Victoria air transports, followed by the sea-transported "D". India was the 1st King's next posting, initially in Jubbulpore. The battalion relocated to Landi Kotal, Khyber Pass, in 1937. Service in the volatile North-West Frontier Province continued into the Second World War.[126]

2nd King's

.JPG.webp)

The 2nd Battalion continued to serve in India following the Armistice and mobilised during the Third Afghan War in 1919. Leading a "Special Column", the battalion reached the Toba Plateau, some 8,000 feet (2,400 m) high, but the war was concluded before the battalion could engage Afghan forces.[127]

Those personnel who remained after the majority demobilised in 1920 joined the Sudan garrison, where the battalion reformed. Postings to Hong Kong and Canton followed in 1922, then to India in 1924, and finally Iraq the next year. Stationed near Baghdad, its residence lasted for two years, uneventful but with the distinction of being the last British battalion to serve there until the Second World War.[125]

Immediately after returning to England, the 2nd King's became the first battalion of the regiment to undertake public duties at Buckingham Palace.[125] The battalion was based in various parts of the country for nearly a decade until 1938, when it became part of the Gibraltar garrison.[128]

Second World War

For the regiment, expansion was on a more modest scale than that of the Great War. Ten battalions (see List of battalions of the King's Regiment (Liverpool)) were formed between 1939 and 1940, including the reconstituted 8th (Liverpool Irish) Battalion. Two of the battalions converted to armour and anti-air roles in 1941: the 11th became the 152nd Regiment in the Royal Armoured Corps, but continued to wear their King's Regiment cap badge on the black beret of the RAC, as did all infantry units converted in this way,[129] while the 12th transferred to the Royal Artillery as 101st Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment.[130]

By late 1941, the regiment had three battalions (1st, 2nd, and 13th) stationed abroad with the remainder poised to defend the United Kingdom against a possible German invasion. The 1st and 13th battalions serve in Burma as Chindits, the 2nd in Italy and Greece during the Greek Civil War, and the 5th and 8th in Western Front of World War II. The 9th Battalion, formed as a duplicate of the 5th in 1939, served with the 164th Brigade, 55th Division, transferring to 165th Brigade in April 1943. Of the battalions that had switched to other roles, only the 40th RTR (7th King's) experienced active service. With the 23rd Armoured Brigade, the 40th RTR fought in the North African Campaign, where they acquired the nickname "Monty's Foxhounds", Italy, and Greece.[131]

Italy and Greece

Having spent five years in Gibraltar with the 1st Gibraltar Brigade, the 2nd Battalion King's departed in December 1943 with the 28th Infantry Brigade (previously 1st Gibraltar Brigade) to reinforce the 4th Infantry Division in Egypt. The battalion landed in Italy with the 4th when the division joined the campaign in March 1944. On 11 May, the division conducted an opposed crossing of the Gari River during the final Fourth Battle of Monte Cassino. The 2nd King's constituted, along with the 2nd Somersets, the main element of 28th Infantry Brigade's initial assault. Behind schedule by 35 minutes and thus lacking artillery support, the battalion attempted to traverse the Gari under sustained mortar and artillery fire.[132] Many boats capsized because of the strong current with resultant losses.[132] The 4th Division collectively struggled to consolidate its bridgehead and minefields and a determined German defence inflicted casualties on the 2nd King's and mortally wounded their commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Garmons-Williams. Depleted and disorganised, the remnants withdrew from an untenable bridgehead on the 14th.[132] The 2nd King's by then had 72 men killed or missing and many wounded.[133][134] After five months and four battles, Monte Cassino was captured on 18 May by the Polish II Corps and the Gustav Line broken.[135]

The Allies captured Rome in June and the 2nd King's fought in the subsequent advance to the Trasimene Line. The King's captured Gioiella in a fierce battle that had involved the 2/4th Hampshires (part of 28th Brigade),[136] and later secured and defended Tuori against counter-attack,[137] earning the regiment a unique battle honour in the British Army.[138] In about nine months of service, in difficult, mountainous terrain, with heavy casualties, the battalion was awarded four DSOs, nine MCs, three DCMs, four MMs, and six mentioned in despatches.[139] Among the recipients were Sergeant Welsby, who single-handedly secured a fortified farmhouse, and Major J. A. de V. Reynolds, for his leadership and conduct around Casa Arlotti.[139]

In December, the 4th Infantry Division was deployed to Greece to reinforce British forces embroiled in the country's civil war. Conflict in Greece between government forces and Communist partisans followed the vacuum created by the German withdrawal. The partisans (ELAS) sought to establish themselves as the new political authority and confronted the British-supported government-in-exile when ordered to disband and disarm.[140] Within 24 hours of being flown to Piraeus on 12 December, the 2nd King's had to engage partisans in a brief action, seizing occupied barracks at a cost of 14 casualties.[141] During a seven-week internal security employment, there were many instances of house-to-house and street fighting in Athens.[141] By mid-January 1945, the city had been cleared of insurgents and a ceasefire agreed upon, followed by the Varkiza Agreement in February.[142] The King's remained for a year to support a tense peace until they left for Cyprus.[143]

Burma

The 13th Battalion, King's Regiment, was raised in October 1940 for coastal defence in England and assigned to the 208th Independent Infantry Brigade (Home). The battalion sailed for India in December 1941, coinciding with Japan's entrance into the war. Intended for internal security and garrison duties, the 13th's strength contained many men categorised as old or of a medically downgraded condition with the result that few men were well trained.[144] After Japan occupied Burma in 1942, the Allies formed a unit intended to penetrate deep behind Japanese lines from India. The 13th King's provided the majority of the British contingent for the "Chindits", which was formally designated as the 77th Indian Infantry Brigade and commanded by Brigadier Orde Wingate.[145]

Organised into two groups, the Chindits' first operation (codenamed Longcloth) began on 8 February 1943. No. 2 Group, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel S.A. Cooke, was formed from the 13th King's and divided into five independent columns, two of which (Nos 7 and 8) were commanded by majors from the battalion.[146] No Japanese opposition was encountered initially, allowing the Chindits to cross the Chindwin River and advance into Burma unimpeded.[147]

The 1st Battalion also took part in a similar operation in 1944 and formed 81 and 82 Columns. As in the first expedition in 1943 the Chindits again suffered heavy casualties and fought behind the Japanese lines at Kohima and Imphal. After Orde Wingate was killed in a crash in March 1944, it was decided to break up the remaining Chindit formations and some of them were to be converted into airborne infantry battalions. The 1st King's was converted to become the 15th (King's) Parachute Battalion of the Parachute Regiment and joined the 77th Indian Parachute Brigade attached to the 44th Indian Airborne Division where it remained for the rest of the war.[148]

Normandy and Germany

In 1943, the 5th and 8th King's (Liverpool Irish) received specialist training at Ayrshire in preparation for a planned invasion of France. They had been selected to form the nucleus of the 5th and 7th Beach Groups, which would have the objectives of maintaining beach organisation, securing positions, and providing defence against counter-attack.[149]

As invasion neared in mid-1944, the two battalions moved from their camps to ports in southern England and embarked aboard troopships and landing ship tanks. Much of the Liverpool Irish embarked aboard the Ulster Monarch, a passenger ship that had served on the Belfast-Liverpool line before the war.[150] Having been delayed, the invasion fleet proceeded to Normandy on 5 June. Both King's battalions landed on D-Day, the 5th at Sword with the 3rd British Infantry Division and the Liverpool Irish at Juno with the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division.[151]

Two companies of the Liverpool Irish landed in the assault wave with the Royal Winnipeg Rifles. Under intense machine gun and mortar fire, the landing of Major Max Morrison's "A" Company proceeded well, allowing some to establish a command-post upon reaching the sand dunes. In contrast, in "B" Company's sector, the late arrival of the reconnaissance party and DD tanks exposed the landing infantry to heavy machine gun fire. The company's officer commanding, Major O'Brien, and the second-in-command were among those wounded.[152] At Sword, as the 3rd Division moved inland, the 5th King's attempted to neutralise hostile positions and snipers. Casualties included Lieutenant-Colonel D. H. V. Board, killed by a sniper, and the OC of 9 Platoon, Lieutenant Scarfe, mortally wounded in an attack on a German position that captured 16 soldiers.[149]

Under fire, the beach groups collected the wounded and dead, located and marked minefields, attempted to maintain organisation, and directed vehicles and troops inland.[149] The two battalions operated with the beach groups for a further six weeks. While the depleted Liverpool Irish disbanded in August, much of its strength having been transferred to other units as reinforcements,[153] the 5th King's survived as a reduced cadre. Disbandment had only been avoided through the determination of Lieutenant Colonel G.D. Wreford-Brown, who argued that the 5th Battalion was nearly the most senior unit active in the Territorial Army.[154]

Before the Allies advanced into Nazi Germany in February 1945, the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) began to form dedicated units to secure important objectives—equipment, installations, intelligence, and personnel.[154][155] The 5th King's provided the nucleus for No. 2 T (Target) Force. Elements of the 5th reached the naval port of Kiel in May 1945, securing the cruiser Admiral Hipper and taking 7,000 sailors prisoner.[156] The battalion continued to conduct intelligence operations until disbandment in July 1946 during the demobilisation process. Reconstitution into the Territorial Army followed in 1947 under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Stanley.[157]

Post-Second World War (1945–1958)

The 1st King's, still roled as 15th (King's) Parachute Battalion, remained in India with responsibility for the area around Meerut, north-east of New Delhi. After reconverting to standard infantry, the battalion departed for Liverpool in late 1947. In April 1948, the 2nd King's deployed to the British Mandate of Palestine for two weeks. The battalion carried out internal security duties in the prelude to Israel's establishment for two weeks before its return to Cyprus.[158] When the army reduced its strength, the 2nd King's chose to be absorbed by the 1st rather than have its lineage terminated. On 6 September 1948, the two battalions amalgamated in a ceremonial parade attended by honorary Colonel of the Regiment, Major-General Dudley Ward.[159] The battalion was posted to West Germany shortly afterwards and moved to West Berlin in February 1951.[143]

Korean War

The battalion was ordered to Korea in June 1952. By then, the Korean War had entered a period of stalemate, with trench warfare prevailing.[160] At Liverpool, the King's embarked aboard the troopship Devonshire for Hong Kong, where it underwent training before landing at Pusan, Korea, in September. Replacing the 1st Royal Norfolk Regiment in the 29th Infantry Brigade, 1st Commonwealth Division,[161] the 1st King's took up defensive positions on moving to the frontline, about 45 miles (72 km) from Seoul.[162]

While much of the battalion's time at the front proved uneventful, its night patrols often clashed with Chinese troops.[162] In 1953, the battalion withdrew to reserve for three months. A tactically important feature known as "The Hook", a crescent shaped ridge, was the scene of intense fighting between Commonwealth forces and the Chinese in May. On the night of 20 May, Chinese forces commenced a sustained bombardment of the Hook, defended by the Duke of Wellington's Regiment. Two days later, a company from the King's conducted a nighttime diversionary raid on Chinese positions known as "Pheasant". During the raid, Second-Lieutenant Caws' 5 Platoon, intended to execute the actual attack, inadvertently stumbled upon an uncharted minefield, suffering 10 wounded from a strength of 16.[163] The attack had to be abandoned, forcing the company to withdraw with its wounded back to British lines under the protection of artillery.[164]

The King's moved to the right sector of the Hook on 27 May, excepting "D" Company's 10 Platoon and "B" Company (as reserve), which became attached to the Dukes. At 1953 hours, on 28 May, the battle began when a heavy artillery barrage targeted the Dukes' positions.[163] Within minutes, the first of four successive Chinese waves attacked. Two King's platoons had to be moved forward to reinforce the Point 121 position, which soon after came under attack by two infantry companies. After the attack was repulsed with the assistance of Commonwealth artillery, the Chinese directed their attention to the King's on Point 146. As their troops assembled at Pheasant at around 2305, 1st King's Lieutenant-Colonel A.J. Snodgrass called in artillery, Centurion tank, and machine-gun fire that effectively destroyed the battalion-sized formation.[165] Fighting continued until the British cleared the remaining troops from the Hook at approximately 0330. British casualties numbered 149, including 28 killed, while Chinese losses were estimated to be 250 killed and 800 wounded.[166]

The 1st King's left Korea for Hong Kong in October, by which time the battalion had suffered 28 dead and 200 wounded. Of some 1,500 men that served with the King's in Korea, 350 were regular soldiers, the rest being conscripts on national service.[163] The King's moved to Britain in 1955, were posted to West Germany the following year, and made its final return home in May 1958.[143]

Amalgamation

The 1957 Defence White Paper (known as the "Sandys Review" after Secretary of State for War Duncan Sandys) announced the government's intention to reduce the army's overseas responsibilities and abolish national service.[167] Regiments and other units were rationalised through amalgamation or disbandment. The decision to merge the King's and Manchesters dismayed many serving and retired personnel.[168] The regiments did, however, share an historical connection through the 63rd (West Suffolk) Regiment of Foot, constituted as the 8th Foot's second battalion in 1756 and redesignated the 1st Battalion, Manchester Regiment in 1881.[169]

In June, at Brentwood, the colours of the two regiments were paraded for the last time in the presence of Queen Elizabeth, The Queen Mother. The King's Regiment (Manchester and Liverpool) formally came into being on 1 September 1958. On 1 July 2006, the successor regiment amalgamated, joining with two others to form the Duke of Lancaster's Regiment.[170]

The surviving territorial battalion of the King's (Liverpool), the 5th, retained its identity until reduced to "B" Company, Lancastrian Volunteers in 1967. The lineage of 5th King's later became perpetuated by "A" Company on its formation in 1992.[44] The company became an integral component of the 4th Battalion, Duke of Lancaster's Regiment in 2006 and contained the Liverpool Scottish Platoon.[171]

Regimental museum

The King's Regiment Museum collection is displayed in the Museum of Liverpool.[172]

Victoria Cross recipients

| Name | Battalion | Date | Location of deed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Harry Hampton | 2nd | 21 August 1900 | Van Wyk's Vlei, South Africa |

| Henry James Knight | 1st | 21 August 1900 | Van Wyk's Vlei, South Africa |

| William Edward Heaton | 1st | 23 August 1900 | Geluk, South Africa |

| Joseph Harcourt Tombs | 1st | 16 May 1915 | Rue du Bois, France |

| Edward Felix Baxter | 1/8th (Irish) | 17/18 April 1916 | Blairville, France |

| Arthur Herbert Procter | 1/5th | 4 June 1916 | Ficheux, France |

| David Jones | 12th (Service) | 3 September 1916 | Guillemont, France |

| Oswald Austin Reid | 2nd | 8/10 March 1917 | Dialah River, Mesopotamia |

| Jack Thomas Counter | 1st | 16 April 1918 | Boisieux St. Marc, France |

Battle honours

The regiment's battle honours were as follows:[44]

- Early battle honours: Blenheim, Ramillies, Oudenarde, Malplaquet, Dettingen, Martinique 1809, Niagara, Delhi 1857, Lucknow, Peiwar Kotal, Afghanistan 1878–80, Burma 1885–87,

- The Boer War: Defence of Ladysmith, South Africa 1899–1902

- The Great War: Mons, Retreat from Mons, Marne 1914, Aisne 1914, Ypres 1914 '15 '17, Langemarck 1914 '17, Gheluvelt, Nonne Boschen, Neuve Chapelle, Gravenstafel, St Julien, Frezenberg, Bellewaarde, Aubers, Festubert 1915, Loos, Somme 1916 '18, Albert 1916 '18, Bazentin, Deville Wood, Guillemont, Ginchy, Flers–Courcelette, Morval, Le Transloy, Ancre 1916, Bapaume 1917 '18, Arras 1917 '18, Scarpe 1917 '18, Arleux, Pilckem, Menin Road, Polygon Wood, Poelcappelle, Passchendaele, Cambrai 1917 '18, St. Quentin, Rosières, Avre, Lys, Estaires, Messines 1918, Bailleul, Kemmel, Bethune, Scherpenberg, Drocourt-Queant, Hindenburg Line, Épehy, Canal du Nord, St Quentin Canal, Selle, Sambre, France and Flanders 1914–18, Doiran 1917, Macedonia 1915–18, NW Frontier, India 1915

- The Inter-war years: Archangel 1918–19, Afghanistan 1919

- The Second World War: Normandy Landing. North-West Europe 1944, Cassino II, Trasimene Line, Tuori, Capture of Forli, Rimini Line, Italy 1944–45, Athens, Greece 1944–45, Chindits 1943, Chindits 1944, Burma 1943–44

- The Korean War: The Hook 1953, Korea 1952–53

Colonels of the Regiment

The colonels of the regiment were:[44]

The Kings (Liverpool) Regiment

- 1881–1889: Gen. John Longfield, CB

- 1889–1891: Gen. Lord Alexander Russell, GCB

- 1891–1899: Gen. George William Powlett Bingham, CB

- 1899–1902: Lt-Gen. Robert Stuart Baynes

- 1902–1906: Lt-Gen. George Edward Baynes

- 1906–1916: Gen. Edward Henry Clive

- 1916–1923: Gen. Sir Henry Mackinnon, GCB, KCVO

The King's Regiment (Liverpool)

- 1923–1940: Gen. Sir Charles Harington Harington, GCB, GBE, DSO

- 1940–1947: Maj-Gen. Clifton Edward Rawdon Grant Alban, CBE, DSO

- 1947-1957: Gen. Sir Dudley Ward, GCB, KBE, DSO

- 1957-1958: Brig. Richard Nicholson Murray Jones, CBE

- 1958: Regiment merged with the Manchester Regiment to form The King's Regiment (Manchester and Liverpool)

Footnotes

- Abbreviations have included L'POOL R, the Liverpools, KLR, and the King's. Usage of "L'POOL R" and "the Liverpools" was most prevalent from the 1880s to the 1920s.

- The other "city" regiments were the Royal Fusiliers (City of London Regiment), the Highland Light Infantry (City of Glasgow Regiment) (from 1923), and the Manchester Regiment.

- These were the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion and the 4th (Extra Reserve) Battalion (both Special Reserve), with the 5th Battalion at St Anne's Street in Liverpool (since demolished), the 6th (Liverpool Rifles) Battalion at Prince's Park Barracks in Liverpool (since demolished), the 7th Battalion at Park Street in Bootle (since demolished), the 8th (Liverpool Irish) Battalion at Shaw Street in Liverpool (since demolished), the 9th Battalion at Everton Road in Liverpool and the 10th (Liverpool Scottish) Battalion at Fraser Street in Liverpool (since demolished) (all Territorial Force).[44]

Notes

- Regimental Marches Archived 19 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Chandler (2003), pp. 188–189

- See the list of British Army regiments for details of the 1881 structure.

- Mileham (2000), pp. 57–9.

- "No. 24992". The London Gazette. 1 July 1881. p. 3300.

- Mileham (2000), p.53

- Mileham (2000), p. 231

- Frederick, pp. 126–8.

- Ray Westlake, Tracing the Rifle Volunteers, (Many pages)

- McConville, Seán (2002), Irish Political Offenders: Theatres of War, p. 342.

- Cannon, Richard & Robertson, Alexander Cunningham (1883), Historical Record of the King's Liverpool Regiment of Foot, pp. 204–5.

- Nevin, Donal (2006). James Connolly, A Full Life: A Biography of Ireland's Renowned Trade Unionist and Leader of the 1916 Easter Rising. Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 9780717162772.

- Raugh, Harold E. (2004),The Victorian's at War, 1815–1914, pp. 70–71.

- "Naval & Military intelligence". The Times (36039). London. 15 January 1900. p. 7.

- Two Famous Regiments, Daily Mail and Empire, 23 November 1895, p.12

- A Sad Return, The Toronto Daily Mail, 2 January 1895, p.1

- Mileham (2000), p.65

- Fremont-Barnes (2003), The Boer War 1899–1902, p. 35.

- Fremont-Barnes (2003), The Boer War 1899–1902, p.36.

- Pakenham, p.106-107

- Fremont-Barnes (2003), The Boer War 1899–1902, p. 73.

- Mileham (2000), p. 68.

- Cassar, George H. (1985), The Tragedy of Sir John French, p. 40.

- A Handbook of the Boer War, pp.53–54.

- Griffith, Kenneth (1974), Thank God We Kept the Flag Flying: The Siege and Relief of Ladysmith, 1899–1900, p.77.

- Mileham (2000), p.69.

- Chisholm (1979), Ladysmith, p. 95.

- Mileham (2000), pp. 69–70.

- (1902), The Rifle Brigade Chronicle, p. 107.

- Fremont-Barnes (2003), The Boer War 1899–1902, p. 40.

- Mileham (2000), p. 73.

- Mileham (2000), p. 74.

- Doyle (1900), The Great Boer War, p. 492.

- Mileham (2000), p. 75.

- Maurice & Grant (1910), History of the War in South Africa, 1899–1902, p. 26.

- Doyle (2004), The Great Boer War, p. 351.

- Copley, limpopomed.co.za. Retrieved 25 March 2007.

- "The War - Infantry and Militia battalions". The Times (36069). London. 19 February 1900. p. 12.

- Parkhouse, p. 297

- "Naval & Military intelligence". The Times (36882). London. 25 September 1902. p. 8.

- "Naval & Military intelligence - The Army in India". The Times (36896). London. 11 October 1902. p. 12.

- "The Army in South Africa - Movement of Troops". The Times (36925). London. 14 November 1902. p. 9.

- "Territorial and Reserve Forces Act 1907". Hansard. 31 March 1908. Retrieved 20 June 2017.

- "King's Regiment (Liverpool)". Archived from the original on 28 December 2007. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- Mileham (2000), pp.240–41.

- The last surviving volunteer battalion, the 7th Isle of Man, mobilised two service companies for Salonika.

- Middlebrook (2000), p.163.

- Coop (1919/2001), p.183.

- Middlebrook (2000), p. 115.

- Middlebrook (2000), p. 40.

- Baker, The New Armies: "Kitchener's Men" Archived 30 June 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Maddocks (1991), p. 24 Full speech Archived 5 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine, mersey-gateway.org. Accessed 28 December 2008.

- Wyrall (2002), pp.2–5.

- Mileham (2000), p. 84.

- Groom, Winston (2003), A Storm in Flanders: The Ypres Salient, 1914–1918: Tragedy and Triumph on the Western Front, p. 63.

- Lomas, First Ypres, 1914, p. 84.

- Neillands, Robin (2005), The Old Contemptibles: The British Expeditionary Force, 1914, pp.318–9

- Neillands, Robin (2005), p.324.

- Carew, Tim (1974), Wipers: First Battle of Ypres, p. 184.

- Wyrall (2002), p

- Mileham (2000), p. 87.

- French, p. 162

- Wyrall (2002), p. 110.

- Mileham (2000), p. 91.

- Wyrall (2002), pp. 113–114.

- Wyrall (2002), p. 123.

- Wyrall (2002), p. 159.

- Tucker, Spencer (2005), Encyclopedia of World War I, p.1247

- Mauroni, Albert J. (2003), Chemical and Biological Warfare: A Reference Handbook, p.6.

- Mileham (2000), pp. 97–98.

- Wyrall (2002), p. 215.

- "Faces of the First World War | First World War Centenary". 1914.org. Retrieved 12 April 2014.

- Sheffield, Gary (2004), The Somme, p.64

- Maddocks (1991), p.208.

- Maddocks (1991), p.88.

- Mileham (2000), p. 106.

- Wyrall (2002), pp. 303–306.

- Wyrall (2002), p.347.

- Giblin (2000), pp. 38–40.

- Mileham (2000), p. 107.

- Wyrall (2004), p. 321.

- Simkins (2002), The First World War, p.17.

- Mileham (2000), p.119.

- Wyrall (2002), pp.389–92.

- Wyrall (2002), pp. 393–402.

- Maddocks (1993), p.149.

- Morrow (2005), The Great War: An Imperial History, p.192.

- Battle of Passchendaele: 31 July – 6 November 1917, bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 13 March 2007

- Mileham (2000), p.123

- Wyrall (2002), p.494.

- Maddocks (1993), p.163.

- Maddocks (1993), p.166.

- Wyrall (2002), p.508.

- McGilchrist, Archibald M. (1930/2005), Liverpool Scottish 1900–1919, p.128.

- Wyrall (2002), p.538.

- Mileham (2000), p. 124

- Samuels, Martin (1995), Command or Control?: Command, Training and Tactics in the British and German Armies, 1888–1918 p. 221

- Wyrall (2002), pp. 607–8

- Wyrall (2002), p. 614

- Robbins, Keith (2002), The First World War, p. 73

- Keegan, John (1998), The First World War, p. 427

- Mileham (2000), p. 125

- Wyrall (2002), p. 618

- Wyrall (2002), pp. 620–1

- Maddocks, Graham (1990), pp. 184–5

- Gray, Randal (1991), Kaiserschlacht 1918: the Final German Offensive, p. 91

- Wyrall (2002), pp. 630–1

- Keegan, John (1990), The First World War, pp. 433–4

- Wyrall, (2002), pp. 641–3

- Mileham (2000), p. 236

- Wyrall, pp. 646–7

- Maddock (1990), pp. 190–1

- Wyrall, p. 651

- Wyrall, pp. 664–8

- Tucker, Spencer (2005), Encyclopaedia of World War I, p. 92

- Wyrall, pp. 672–3

- Herbert Glynne Roberts (1922), The Story of the 9th King's in France, p.124.

- Wyrall, (2000), pp. 702–3.

- Wyrall (2002), pp.693–4

- Roberts (1922), The Story of the 9th King's in France, p. 127.

- Mileham (2000), p. 138.

- Mileham (2000), p.128.

- Mileham (2000), pp. 131–2.

- Barry (1993), Guerilla Days in Ireland, p. 99.

- Mileham (2000), p. 133.

- "King's Regiment (Liverpool)". National Army Museum. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- Wyrall, (1935/2000), p. 697.

- Shepperd, p. 27

- George Forty (1998), "British Army Handbook 1939–1945", Stoud: Sutton Publishing, pp. 50–1.

- Frederick, John Bassett Moore (1969), Lineage book of the British Army; Mounted Corps and Infantry, 1660–1968, p. 111

- "Local regiments". Liverpool And Merseyside Remembered. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- Ellis, John (2003), Cassino: The Hollow Victory, pp. 299–300.

- Graham (2004), Tug of War: The Battle for Italy 1943–45, p. 179.

- Mileham (2000), p. 176.

- Fisher, Jr., Ernest F. (1993), Mediterranean Theater of Operations: Cassino to the Alps, p.78.

- Playfair, Ian Stanley Ord (1987), The Mediterranean and Middle East, p. 44

- Cook, Hugh C.B. (1987), The Battle Honours of the British and Indian Armies, 1662–1982, p. 400.

- The History of the Duke of Lancaster's Regiment Archived 20 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Mileham (2000), p. 179.

- Iatrides, John O. & Wrigley, Linda (2004), Greece at the Crossroads: the Civil War and its Legacy, p. 9.

- Mileham (2000), pp. 179–180.

- Clogg, Richard (2002), A Concise History of Greece, p. 134.

- "King's Regiment (Liverpool)". British Army units 1945 on. Retrieved 2 January 2016.

- Mileham (2000), p. 145.

- "77 Brigade". Order of Battle. Archived from the original on 6 July 2007. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- Mileham (2000), p. 155. Majors Ken Gilkes and Walter 'Scotty' Scott commanded Nos 7 and 8 Columns respectively. Scott would subsequently command the 1st King's in 1944.

- (2002), The Second World War: Asia and the Pacific, p. 216.

- "77 Brigade Subordanates". Order of Battle. Archived from the original on 4 January 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- Mileham (2000), pp. 165–166.

- Fitzsimmons (2004), p. 44.

- Granatstein, p. 56

- Fitzsimmons (2004), p. 49.

- Mileham (2000), p. 167.

- 5 King's/No 2 T Force (Archive), army.mod.uk. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- Ziemke, Early F. (1990) [1975]. "Chapter XVII Zone and Sector". The U.S. Army in the Occupation of Germany 1944–1946. American Historical Series. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. p. 313. CMH Pub 30-6.

- Mileham (2000), p. 172.

- Mileham (2000), p. 181.

- Mileham (2000), p. 183.

- Mileham (2000), pp. 182–183.

- The Korean War: An Encyclopedia, p.7

- McInnes, Colin (1996), Hot War, Cold War: The British Army's Way in Warfare, 1945–95, p.191

- Mileham (2000), pp.189–90

- Mileham (2000), pp. 191–2.

- Barker (1974), Fortune Favours the Brave — the Battle of the Hook, Korea, 1953, p. 105.

- Gaston, Peter (1976), Thirty-Eighth Parallel: The British in Korea, p.65

- Jaques, Tony (2007), Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: F-O, p.455

- Chandler (2003), p. 338.

- Mileham (2000), p.193.

- "No. 24992". The London Gazette. 1 July 1881. pp. 3300–3301.

- "Duke of Lancaster's Regiment". Archived from the original on 21 November 2008. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- A Brief History of The Liverpool Scottish Archived 3 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "City Soldiers". Museum of Liverpool. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

References

- Baker, Chris, The King's (Liverpool Regiment) in 1914–1918, 1914–1918.net. Retrieved 8 November 2005

- Chandler, David (2003), The Oxford History of the British Army, Oxford Paperbacks ISBN 0-19-280311-5

- Coop, J.O. (1919/2001), Story of the 55th (West Lancashire) Division, Naval and Military Press ISBN 1-84342-230-1

- Fitzsimons, Jim (2004), A Personal History of the 8th Irish Battalion, The King's Liverpool Regiment, ISBN 0-9541111-1-7

- French, Lord, (2001), Complete Despatches of Lord French 1914-1916, Naval and Military Press, ISBN 978-1843420989

- Granatstein, J.L. and Morton, Desmond [1984] (1994). Bloody Victory: Canadians and the D-Day Campaign 1944. Toronto: Lester Publishing Limited. ISBN 1-895555-56-6

- Maddocks, Graham (1991), Liverpool Pals: 17th, 18th, 19th and 20th Battalions, The King's (Liverpool Regiment), Pen and Sword Books Ltd ISBN 0-85052-340-0

- Middlebrook, Martin (2000), Your Country Needs You!: Expansion of the British Army Infantry Divisions 1914–1918, Pen and Sword Books Ltd ISBN 0-85052-711-2

- Mileham, Patrick (2000), Difficulties Be Damned: The King's Regiment—A History of the City Regiment of Manchester and Liverpool, Fleur de Lys ISBN 1-873907-10-9

- Pakenham, Thomas; The Boer War, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1979, ISBN 0-7474-0976-5

- Parkhouse, Valerie (2015). Memorializing the Anglo-Boer War of 1899-1902: Militarization of the Landscape, Monuments and Memorials in Britain. Matador. ISBN 978-1780884011.

- Shepperd, Alan (1973). King's Regiment. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-0850451207.

- Wyrall, Everard (1935/2002), The History of the King's Regiment (Liverpool) 1914–19, Naval and Military Press ISBN 1-84342-360-X

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to The King's Regiment. |

- City Soldiers – The Museum of Liverpool Life

- Liverpool Scottish Regimental Museum Trust, liverpoolscottish.org.uk

- Korean War Roll of Honour: The King's Regiment (Liverpool), britains-smaillwars.com

- Enos Herbert Glynne Roberts (1922), The Story of the 9th King's in France, The Northern Publishing Co. Ltd, Project Gutenberg

- 1st Battalion, the King's (Liverpool Regiment) War diary 1 January to 3 June 1916