Kumeyaay

The Kumeyaay, also known as Tipai-Ipai, are a tribe of Indigenous peoples of the Americas who live at the northern border of Baja California in Mexico and the southern border of California in the United States. Their Kumeyaay language belongs to the Yuman–Cochimí language family.

Anthony Pico, chairman of the Viejas Band of Kumeyaay | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| As of 1990, 1,200 on reservations; 2,000 off-reservation[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Ipai, Kumeyaay, Tipai, English, and Spanish | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Luiseño, Cocopa, Quechan, Paipai, and Kiliwa |

The Kumeyaay consist of three related groups, the Ipai, Tipai, and Kamia. The San Diego River loosely divided the Ipai and the Tipai historical homelands, while the Kamia lived in the eastern desert areas. The Ipai lived to the north, from Escondido to Lake Henshaw, while the Tipai lived to the south, in lands including the Laguna Mountains, Ensenada, and Tecate. The Kamia lived to the east in an area that included Mexicali and bordered the Salton Sea.

Name

The Kumeyaay or Tipai-Ipai were formerly known as the Kamia or Diegueños, the former Spanish name applied to the Mission Indians living along the San Diego River.[2] They are referred to as the Kumiai in Mexico.

The term Kumeyaay translates as "Those who face the water from a cliff", with the word meyaay meaning "steep" or "cliff".[3]

Language

All languages and dialects spoken by the Kumeyaay belong to the Delta–California branch of the Yuman language family, to which several other linguistically distinct but related groups also belong, including the Cocopa, Quechan, Paipai, and Kiliwa. Native speakers contend that within their territory all Kumeyaay (Ipai/Tipai) can understand and speak to each other, at least after a brief acclimatization period.[4]

Nomenclature and tribal distinctions are not widely agreed upon. According to Margaret Langdon, who is credited with doing much of the early work on documenting the language,[5][6] the general scholarly consensus recognized three separate languages: Ipai (Iipay) (Northern Kumeyaay), Kumeyaay proper (including the Kamia/Kwaaymii), and Tipai (Southern Kumeyaay) in northern Baja California. Katherine Luomala considered that the wide range of dialect variations reflected only two distinct languages Ipai and Tipai, Luomala 1978 a view supported by other researchers.[7][8]

History

Pre-European Contact

Evidence of the settlement in what is today considered Kumeyaay territory may go back 12,000 years.[9] 7000 BCE marked the emergence of two cultural traditions: the California Coast and Valley tradition and the Desert tradition.[10] The Kumeyaay had land along the Pacific Ocean from present Oceanside, California in the north to south of Ensenada, Mexico and extending east to the Colorado River.[11] The Cuyamaca complex, a late Holocene complex in San Diego County is related to the Kumeyaay peoples.[12] The Kumeyaay tribe also used to inhabit what is now a popular state park, known as Torrey Pines State Natural Reserve.[13]

One view holds that historic Tipai-Ipai emerged around 1000 years ago, though a "proto-Tipai-Ipai culture" had been established by about 5000 BCE.[1] Katherine Luomola suggests that the "nucleus of later Tipai-Ipai groups" came together around AD 1000.[10] The Kumeyaay themselves believe that they have lived in San Diego for 12,000 years.[14] At the time of European contact, Kumeyaay comprised several autonomous bands with 30 patrilineal clans.[15]

Spanish Exploration and Colonization

The first European to visit the region was Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo in 1542 and met with the Kumeyaay, but did not lead to any colonial settlement. Sebastian Viscaino also visited in 1602 and met with a band Kumeyaay during the feast of San Diego de Alcala, giving the region of San Diego its name, but this also did not accumulate to colonial settlement.

In 1769, the Portolá expedition landed in the San Diego Bay and arrived to the Kumeyaay village of Cosoy (Kosa'aay) to recover and resupply. After their recovery, the Spanish established a presidio over the village and the Mission San Diego de Alcalá, incorporating the village into the settlement of San Diego. Under the Spanish Mission system, bands living near Mission San Diego de Alcalá, established in 1769, were called Diegueños, and later bands living near Mission San Luis Rey de Francia were called Luiseño.[15] The Spaniards brought with them non-native, invasive flora, and domestic animals, which brought about degradation to local ecology.

After years of sexual assaults from the Spanish soldiers in the Presidio and physical torture of Mission Indians using metal-tipped whips by Mission staff,[16] the Tipai-Kumeyaay villages led a revolt against the Spanish, burning down Mission San Diego and killing Father Luis Jayme and two others. Missionaries and church leaders forgave the Kumeyaay and rebuilt the mission by the Kumeyaay village of Nipaquay or Nipawai. However, the Spanish solidified their control over the area to the end of the Mission Era.[17]

First Mexican Empire and First Mexican Republic period

The Mexican Empire assumed ownership of Kumeyaay lands after defeating Spain in the Mexican War of Independence in 1821. The following year, Mexican troops confiscated all coastal lands from the Kumeyaay in 1822, granting much of the land to Mexican settlers, who became known as Californios,[18] to develop the land for agriculture, beginning the California Rancho Era.

Kumeyaay fell victim to smallpox and malaria epidemics in 1827 and 1832, reducing the Kumeyaay population.[19]

Various disputes culminated to a skirmish between the Kumeyaay and Mexican soldiers stationed in San Diego in 1826, killing 26 Kumeyaay.[19] This provoked Lt. Juan M Ibarra to lead several attacks on Kumeyaay-controlled lands, killing 28 people in his attack on Santa Ysabel.[20]

After decades of debates and delays, the missions in Alta California were secularized in 1833, and Ipai and Tipais lost their lands; band members had to choose between becoming serfs, trespassers, rebels, or fugitives.[21] This increased tensions between the Kumeyaay and the Mexican settlers as the Kumeyaay economic instability threatened the security of Mexican and American merchants transiting through the area.

Centralist Republic of Mexico period

Under territorial governor Jose Figueroa Some of the Kumeyaay from Mission San Diego were allowed to resettle and establish San Pasqual Pueblo in 1835, who would later become the San Pasqual Band of Diegueno Mission Indians.[22] The Kumeyaay Pueblo fought against hostile bands and protected Mexican settlers, with a decisive victory over an anti-Christian uprising and capturing its leader, Claudio.[23]

With conditions worsening, the Kumeyaay led an attack on Rancho Tecate in 1836, forcing the alcalde of San Diego to send an expedition to suppress the Kumeyaay, but returned unsuccessfully. Because of the failed venture, Mexico failed to adequately suppress talk of Californian secession from American settlers in Northern Alta California.[20]

Further Kumeyaay raids on El Cajon (1836) and Rancho Jamul (1837) threatened the security of San Diego, as many residents of San Diego fled the city. The Kumeyaay were able to attack San Diego in the late 1830's. Kumeyaay advancements into Rancho Bernardo in the North and San Ysidro and Tijuana to the South at the end of the decade threatened to cut off San Diego from the rest of the Centralist Republic of Mexico. The Kumeyaay made preparations to lay siege on San Diego in the early 1840s and launched a second attack on San Diego in June 1842. However, San Diego managed to defend itself once more. The Kumeyaay prevented Mexican usage of the ranchos around San Diego and evicted most of the Californios in the area by 1844, and continued launching raids deep into the Mexican controlled coast up until the start of the Mexican-American War.[20]

Mexican-American War

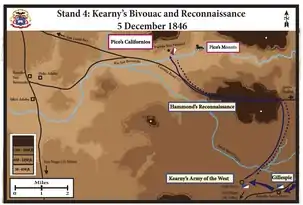

During the Mexican-American War, the Kumeyaay were initially neutral. The Kumeyaay of the San Pasqual pueblo were evacuated as the Americans approached the town. The Mexicans and the Californios were victorious over the Americans at the Battle of San Pasqual. A Kumeyaay leader, Panto, called on the Mexicans to cease hostilities with the Americans so that the Kumeyaay could tend to the wounded Americans, to which provided Panto and the San Pasqual Kumeyaay resupplied the Americans and helped ensure the American capture of the Pueblo de Los Ángeles and San Diego.[22][23]

Modern American & Mexican Era

After the Mexican-American War, Kumeyaay lands were split between the US and Mexico through the Mexican Cession resulting from the Treaty of Guadalupe Hildago.

In 1851, the San Diego County unilaterally charged property taxes on Native American tribes in the county and threatened to confiscate land and property should they fail to pay up. This led to the San Diego Tax Rebellion of 1851 or "Garra's Revolt", with the destruction of Warner's Ranch led by the Cupeño, beginning the first stage of the Yuma War. The Kumeyaay agreed to join the revolt along with the Cocopah and Quechan, but made no military commitments to attack San Diego or capture Fort Yuma.[24][25]

Instead, the San Pasqual Band of Kumeyaay fought against the Quechan campaign to attack San Diego and defeated the Quechan in the San Pasqual Valley.[26]

Compared to other California tribes, the Kumeyaay did not face the same magnitude of destruction and exploitation under the California Genocide. This was due to the strategic positioning of the Kumeyaay and the lack of gold in the mountains. Additionally, Mexican officials threatened to intervene in the conflict if they committed any atrocities on tribes along the border, due to a mix of Mexican sympathies towards the Native Californians and a fear of refugees coming across the border.[27]

Establishment of Kumeyaay Reservations in the U.S.

On January 7, 1852, representatives of a number Kumeyaay clans, including Panto, met with Commissioner Oliver M. Wozencraft and negotiated the Treaty of Santa Ysabel. The agreement was part of the famous “18 Treaties” of California, negotiated to protect Indian land rights. After the 18 Treaties were completed, the documents were sent to the United States Senate for approval. Under pressure from white settlers and the California Senate delegation, the treaties were all rejected.[22]

From 1870 to 1910, American settlers seized lands, including arable and native gathering lands. In 1875, President Ulysses S. Grant created reservations in the area, and additional lands were placed under trust patent status after the passage of the 1891 Act for the Relief of Mission Indians. The reservations tended to be small and lacked adequate water supplies.[28] The situation was made worse during the famine of 1880-1881, which forced many Kumeyaay to survive by accepting charity from whites, as they faced diseases, starvation, and attacks from White settlers.[29]

In 1932, the Coapan Kumeyaay living on the San Diego River were removed to make way for the El Capitan Dam and Reservoir and relocated their inhabitants at the Barona Reservation and the Viejas Reservation.[19]

Kumeyaay in the Mexican Revolution (1910-1911)

During the Mexican Revolution, the Magonistas gained the support of the Kumeyaay with an enthusiastic base particularly in the Tecate region, many Kumeyaay from both sides of the border were enticed by their anarcho-syndicalist message of indigenous liberation from the Mexican and American colonial nation-states starting with the end of the Porfirio Díaz dictatorship. The Kumeyaay supported the Magonistas as guides throughout the land, whose aid allowed them to control Mexicali, Tecate, and Tijuana during the Magonista Rebellion of 1911.[30] However, the Kumeyaay did not participate in much of the active fighting in the Magonista Rebellion, and did not participate with Cocopah, Kiliwa, and Paipai tribes in raiding on small towns or looting Chinese-Mexican businesses in the region, and may have even smuggled Chinese-Mexican refugees to the American side of the border.[30] By the end of June, the rebellion was suppressed by the Madero Administration.

After the revolution, the ban on Ejidos and other forms of communal living were lifted and the Kumeyaay were able resume their traditional communal way of life legitimately with their communities in Valle de Las Palmas, Peña Blanca, and their five other reservations.[31]

Kumeyaay-American Economy and Casino Industry

Kumeyaay people supported themselves by farming and agricultural wage labor; however, a 20-year drought in the mid-20th century crippled the region's dry farming economy.[32] For their common welfare, several reservations in the US formed the non-profit Kumeyaay, Inc.[33]

Cuts in Native American welfare programs under the Reagan and Bush Sr. administrations forced reservation to find other means of income and capitalize on industries not possible off-reservation.[34]

In 1982, the Barona Band won its case in the Barona Group of the Capitan Grande Band of Mission Indians v. Duffy (1982) to operate high-stakes bingo games, leading to the expansion of many Kumeyaay bingo operators into the Casino industry. This helped establish Vegas-style gaming operations in the reservations in the region, evaporating reservation unemployment and poverty in a short time. In total, the Kumeyaay operate six casinos: Barona Valley Ranch Resort and Casino, Sycuan Resort and Casino, Viejas Casino & Resort, Valley View Casino and Hotel, Golden Acorn Casino and Travel Center, and Jamul Casino.[34]

Kumeyaay-Mexican Economy and Wine Tourism Industry

On the Mexican side of the border, Kumeyaay reservations manufacture traditional craftwork to sell on the American side of the border with partnering Kumeyaay souvenir gift shops and casinos.[35]

Many Kumeyaay there have moved into urban areas to seek better employment opportunities compared to their agrarian employment on the reservation. The depopulation of their reservations have allowed neighboring non-native Ejidos to encroach on their lands.[36]

The Kumeyaay reservations on the Mexican side of the border have largely retained their traditional heritage. Some reservations faced water shortages, making it difficult to continue agricultural operation. This led many communities to enter wine-tasting and tourism industries in the Guadalupe Valley.[37] Many bands began launching wine tours and festivals to attract tourists and foreign visitors from Southern California and cruise passengers stopping at the Port of Ensenada.[31]

Kumeyaay and the US-Mexican Border

In 1998, the Kumeyaay established the Kumeyaay Border task force to work with federal immigration officials to secure free passage of Baja Kumeyaay bands to visit the US Kumeyaay bands and ensure their rights to protected graves and artifacts protected by the Native American Grave Protection and Repatriation Act of 1990.[19]

However, border wall construction accelerated in 2020 and Kumeyaay representatives at the border to protect and preserve Kumeyaay artifacts were turned away from the construction area. This sparked protests among the bands and Kumeyaay women organized to lead a protest at the border in July. The La Posta Band filed a lawsuit in August against the Trump administration seeking to block further construction of the border wall through their sacred cemetery (burial sites).[38]

Society

Social Structure

Prior to Western assimilation, the Kumeyaay were organized into bands or clans called sibs or shiimull, which were grounded in family lineages with each sib home for 5 to 15 families. Each sib had their own territory and had the right to enforce land property rights in punishing thieves and trespassers. However, Kumeyaay did recognize the right to water and were also obligated to share food with visitors.[39]

The Kumeyaay had a patriarchal society where the position of chief, or Kwaapaay, was inherited from the father to son, although widows were sometimes permitted to assume the position. It was the kwaapaay's role to protect traditions, hold ceremonies, and resolve disputes and was responsible for political, religious, and economic activities of the sib. Future Kwaapaays were often selected by a Kwaapaay of another with no family relations to ensure impartiality.[39]

Kwaapaays were also accompanied by assistants and had a council of Kuseyaays. Kuseyaays were made up of male or female priests, doctors, and other specialists in the fields of health, ecology, resource management, tradition, and religion. Kuseyaays could be called by the kwaapaay to provide information or to make decisions for the sib's welfare. Each family in the sib was allowed to follow and participate in the decision making, or could leave the sib and pursue their own decision.[39]

The Kumeyaay practiced arranged marriage made by parents of different sibs. The future husband was expected to demonstrate his ability to hunt and needed to present the future bride the game he had killed. The bride would move into the husband's sib once they were married. Marriage relations were also made between sibs and other neighboring tribal groups as a gesture of peace between warring groups or as part of a trade relationship.[40]

Shelter

The Kumeyaay generally lived in dome-shaped homes made from branches and covered with leaves of willow or tule, which the Kumeyaay called 'ewaa. These structures had a hole at the top to let smoke out and rocks along its base to keep out wind and small animals.[40] Some Kumeyaay who lived in the mountains made their home out of slabs of bark.[3]

These structures were often temporary, as they burned down their homes when families moved or if someone died in the house.[40]

Clothing

During warm seasons, men wore nothing except for a hide breechcloth to hold tools while women wore an apron or a skirt made from willow or elderberry bark. In the colder months, they would wear blankets made from willow bark or rabbit skins.

They wore agave sandals made from yucca and agave fibers when going over long distances, over sharp rocks, or hot sand. Some would wear bead necklaces as jewelry, with beads made of clam, abalone, or olivella shells. Additionally, men could get their nose pierced and women might have their chins tattooed.

The Kumeyaay started to abandon much of their traditional clothing after coming in contact with the Spanish, and adopted European-style clothing, wearing clothes that were normal in Latin America.[40]

Diet

Acorns were a staple of the Kumeyaay diet, and made acorn mush they called shawii, which could be used in dough to make bread by grinding with a mano and a metate. Other grains like pinon nuts or chia seeds were also stone-ground and consumed.[3] The Kumeyaay stored these grains in basket granaries made of willow leaves. They also consumed the leaves and fruits of the prickly pear and copal cactus, as well as cherries, plums, elderberries, and Manzanita berries.[41]

They hunted for animals such as birds, rabbits, squirrels, and woodrats, as well as larger animals like antelope, deer, and mountain sheep. The Kumeyaay also ate more nutrient-rich insects such as crickets, grubs, and grasshoppers.[40]

Kamia Kumeyaay in the Imperial Valley practiced some forms of agriculture, producing maize, beans, and teparies. Although, like other Kumeyaay, they largely relied on gathering.[41]

Economy and Communication

The Ipai-Tipai Kumeyaay traded with the Kamia Kumeyaay to obtain obsidian from an area south of the Salton Sea. Within the Tipai-Ipai, the coastal Kumeyay traded salt, seaweed, and abalone shells for acorns, agave, mesquite beans, and gourds from the mountain Kumeyaay. They also traded along the Pacific coast to obtain Olivella shell beads from the Chumash, as well as tribes along the Gulf of California and in the American Southwest as far east as to trade with the Zuni.[3] Granite was also plentiful in Kumeyaay lands, which were used to trade for pestles, steatite, eagle feathers, and colored minerals for paint.[41]

The Kumeyaay's maritime economy relied on shell fishing, and built fishing boats of either balsa rafts made of reeds or dugout canoes.[41] To support their maritime economy, they manufactured fishing spears, hooks, and nets made of agave fiber.[40]

Upon Spanish arrival, woven baskets were highly prized by the Europeans, as these baskets were so well made that they could hold water and it was possible to cook food with these baskets in an open fire. The strong demand for Californian woven baskets in Mexican and European markets strengthened the basket weaving economy among the Kumeyaay.[3]

The Kumeyaay had a system of trail runners who carried messages and announcements between bands, which notified the presence of the Spaniards prior to Cabrillo's arrival in San Diego.[3]

Weaponry

The Kumeyaay were skilled in archery in order to hunt prey. Their arrows were made of wood, cane, or reeds, as well as chamise or greasewood plant for larger animals. Bows were made of mequite or ash, as well as animal hides. They also equipped with throwing sticks better known as rabbit sticks, which were used to knock out small animals and were sometimes used in war.[40]

Culture

The Kumeyaay has a continuous song and dance culture, of which many are still passed on to the next generation during special occasions. Occasions like the mourning of an important figure was honored by an Eagle Dance, and a War Dance accompanied those heading for battle. Men often sang songs with a rattle, while women supported the song through dance. Through the Mission, the Kumeyaay picked up skills in Western musical instruments, and joined the Mission choirs and orchestras.[40]

They also had animal companions and domesticated mockingbirds and roadrunners as pets.

Reservation Era Kumeyaay Institutions

The Kumeyaay Community College was created by the Sycuan Band to serve the Kumeyaay-Diegueño Nation, and describes its mission as "to support cultural identity, sovereignty, and self-determination while meeting the needs of native and non-Native students." The college's focus is on "Kumeyaay History, Kumeyaay Ethnobotany and traditional Indigenous arts." It "serves and relies on resources from the thirteen reservations of the Kumeyaay Nation situated in San Diego county."[42] In the fall of 2016, Cuyamaca College began offering an associate degree in Kumeyaay Studies with courses at its Rancho San Diego campus, as well as at Kumeyaay Community College on the Sycuan reservation.[43]

The Sycuan Institute on Tribal Gaming was also established at SDSU by the Sycuan Band with the focus on research and policy related to the tribal gaming industry.

Population

Estimates for the pre-contact populations of most native groups in California have varied substantially. In 1925, Alfred L. Kroeber proposed that the population of the Kumeyaay in the San Diego region in 1770 had been about 3,000.[44] More recently, Katharine Luomala points out that this estimate depended on calculations of rates of baptisms at the Mission, and as such "ignores the unbaptized." She suggests that the region could have supported 6,000-9,000 people.[45] Florence C. Shipek goes further, estimating 16,000-19,000 inhabitants.[46]

In the late eighteenth century, it is estimated that the Kumeyaay population was between 3,000 and 9,000.[1] In 1828, 1,711 Kumeyaay were recorded by the missions. The 1860 federal census recorded 1,571 Kumeyaay living in 24 villages.[45] The Bureau of Indian Affairs recorded 1,322 Kumeyaay in 1968, with 435 living on reservations.[45] By 1990, an estimated 1,200 lived on reservation lands, while 2,000 lived elsewhere.[1]

Tribes and reservations

Kumeyaay Villages

Village Origin of Modern Cities

Other Former Villages in the US

In the City of San Diego

- Nipaquay | Mission Valley

- Choyas | Barrio Logan

- Utay | Otay Mesa

- Jamo | Pacific Beach

- Ystagua | Sorrento Valley

- Melijo | Tijuana River Valley

- Onap | San Clemente Canyon

- Tisirr | Downtown San Diego

- Totakamalam | Point Loma

- Sinyau-Pichkara | Rancho Bernardo

- Awil-Nyawa | Rancho Penasquitos

- Ahwel-Awa | North City, San Diego

- Hatam's Village (within the former Native American neighborhood in San Diego) | Balboa Park

In the County of San Diego

- Chiap/Chyap | Chula Vista

- Meti | National City, California

- Neti | Spring Valley, San Diego County, California

- Apusquel | Bonita, California

- Tapin/Jacunmat | El Cajon

- Matamo | El Cajon near Dehesa, California

- Alyshuhwi | Imperial Beach

- Jayal | Olivenhain, Encinitas

- Hakutl | Encinitas

- Kulaumai | Solana Beach

- Ajopunquile (Possibly Payómkawichum) | La Costa

- Jamacha

- Canapu | Ramona, California

- Epegam | Ballena, California

- Japatul

- Cojuat

- Hakwa | Anza-Borrego

- Hortluke | near Ranchita

- Winal | near Ocotillo Wells

- Wi-i | near Ocotillo Wells

- Kwpol | Imperial, California

- Sitcarknyewa | Near Brawley, California

- Matakal | Near Rockwood, California

- Hacamikalau

Other Former Villages in Mexico[50]

In the Municipality of Tijuana

- Kwa-kwa | Cuero de Venado

- Wanya pu:wam | Cerro de Bonifacia

- We-ilmex

In the Municipality of Tecate

- Mat'haina:l | Villareal de San José

- Cikaú | Tanama

- Mat'kwoho:l | Cañon Manteca

- Uap 'cu:l uit | Cañon Manteca

- Ja-kwak-wak | Las Juntas

- Ha'kumum | Agua Tule

- Metot'tai | Valle de las Palmas

- Kwat' Kunšapax | Las Calabazas

- Cukwapa:l | El Compadre

- 'Ui'ha'tumer

- Mutu Cata | Cañon del Cansio

- Jat'ám | Santa Clara

- Ha'mat'tai | Jamatay

- Ha'kume | Ejido Jacume

In the Municipality of Mexicali

- Hwat Nyaknyuma

- Wekwilul

- Hakwisiay

In the Municipality of Ensenada

- Jhlumúk | Valle de Guadalupe

- Jiurr-jiurr | Agua Escondida

- Kwar Nuwa | El Sauzal

- 'Ui'cikwar | Real del Castillo

- Yiu kwiñi:l | Ojos Negros

- Ha'cur | San Salvador

See also

- Kumeyaay traditional narratives

- Kumeyaay astronomy

- O. M. Wozencraft negotiated the Treaty of Santa Ysabel on January 7, 1852.[51]

- Sycuan Institute on Tribal Gaming at San Diego State University

- Viejas Arena at San Diego State University

- Viejas casino

Notes

Citations

- Pritzker 2000, p. 145

- User, Super. "The Indians of San Diego County". www.kumeyaay.com.

- Hoffman, Geralyn Marie (2006). A Teacher's Guide to Historical and Contemporary Kumeyaay Culture (PDF). San Diego State University: Institute for Regional Studies of the Californias.

- Smith 2005

- "Margaret Langdon; linguist helped write first local Indian dictionary | The San Diego Union-Tribune". legacy.sandiegouniontribune.com. Archived from the original on 2016-10-11. Retrieved 2016-10-10.

- Langdon 1990.

- Pritzker 2000.

- Field 2012, p. 557.

- Erlandson et al. 2010, p. 62

- Luomala 1978, p. 594

- "KUMEYAAY MAP 1776 Kumeyaay Territory, 2005 California Indian Reservations". www.kumeyaay.info.

- "A Glossary of Proper Names in California Prehistory." Society for California Archaeology. (retrieved 12 Aug 2011)

- "Native Americans", Torrey Pines State Natural Reserve, retrieved 10 October 2016

- "The Kumeyaay of Southern California", The Kumeyaay Information Villages, retrieved 10 October 2016

- Luomala 1978, p. 592

- Yagi, George (2017-10-11). "The Battle for San Diego". HistoryNet. Retrieved 2020-09-02.

- "Sociopolitical Aspects of the 1775 Revolt at Mission San Diego de Alcala". San Diego History Center | San Diego, CA | Our City, Our Story. Retrieved 2020-09-02.

- Gurling, Sara (2018-11-22). "Give Thanks and Remember Your Cousins". Latino Rebels. Retrieved 2020-09-03.

- "Kumeyaay Timeline". www.kumeyaay.com. Retrieved 2020-09-02.

- Connolly, Mike. "Kumeyaay - The Mexican Period". www.kumeyaay.com. Retrieved 2020-10-16.

- Luomala 1978, p. 595

- "History". www.sanpasqualbandofmissionindians.org. Retrieved 2020-09-02.

- Farris, Glenn. "CAPTAIN JOSE PANTO AND THE SAN PASCUAL INDIAN PUEBLO IN SAN DIEGO COUNTY 1835-1878". San Diego History Center | San Diego, CA | Our City, Our Story. Retrieved 2020-09-02.

- "The Indian Tax Rebellion of 1851". HistoryNet. 2006-06-12. Retrieved 2020-09-03.

- "San Diego History : Garra's Uprising". Los Angeles Times. 1992-08-10. Retrieved 2020-09-03.

- "Kumeyaay Sense of the Land and Landscape". Viejas Band of Kumeyaay Indians. Retrieved 2020-09-03.

- Connolly, Mike. "Kumeyaay - California Genocide". www.kumeyaay.com. Retrieved 2020-10-16.

- Shipek 1978, p. 610

- Connolly, Mike. "The Kumeyaay Threat of 1860-1880". www.kumeyaay.com. Retrieved 2020-10-16.

- Muñoz, Gabriel Trujillo (2012). La utopía del norte fronterizo: La revolución anarcosindicalista de 1911. San Ángel, Del. Álvaro Obregón, México, 01000, D. F: Instituto Nacional de Estudios Históricos de las Revoluciones de México. pp. 30–31. ISBN 978-607-7916-83-3.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Kumeyaay Land: Baja California's Endangered Rural Heritage". www.sohosandiego.org. Retrieved 2020-09-02.

- Shipek 1978, p. 611

- Shipek 1978, p. 616

- Banegas, Ethan. "Indian Gaming in the Kumeyaay Nation". San Diego History Center | San Diego, CA | Our City, Our Story. Retrieved 2020-09-02.

- "SAN ANTONIO NECUA Baja California Mexico Kumeyaay Indians Documentary Kumiai Photos Pictures". www.kumeyaay.info. Retrieved 2020-09-02.

- "Juntas de Nejí". www.kumeyaay.com. Retrieved 2020-09-02.

- "Native Kumiai Finding a New Way - The Baja Storyteller". Baja Bound Insurance Services. Retrieved 2020-09-02.

- Srikrishnan, Maya (2020-08-17). "Border Report: Kumeyaay Band Sues to Stop Border Wall Construction". Voice of San Diego. Retrieved 2020-09-02.

- Pico, Anthony. "The Kumeyaay Millennium - Land History". www.americanindiansource.com. Retrieved 2020-10-31.

- Bacich, Damian (2019-11-13). "Native Americans of Southern California: the Kumeyaay |". The California Frontier Project. Retrieved 2020-10-31.

- "Tipai-Ipai (Native Americans of California)". what-when-how.com. Retrieved 2020-11-29.

- Kumeyaay Community College, retrieved October 10, 2016

- Huard, Christine (15 August 2016). "College expands Kumeyaay studies program". The San Diego-Union Tribune. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- Kroeber 1925, p. 88

- Luomala 1978, p. 596

- Shipek 1986, p. 19

- "Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs Notice 145A2100DD/A0T500000.000000/AAK3000000: Indian Entities Recognized and Eligible to Receive Services from the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs". Federal Register, January 2015 (PDF). Federal Register. 80. Government Publishing Office. January 14, 2015. pp. 1942–1948. OCLC 1768512. Retrieved October 8, 2016.

- "U.S. Census website". Retrieved 2017-03-21.

- Ray, Nancy (1989-12-23). "Last Full-Blooded Kwaaymii Indian Dies at 87". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2020-11-28.

- "bajacalifology.org - Kumeyaay Place Names". www.sandiegoarchaeology.org. Retrieved 2020-09-01.

- Carrico, Richard L. (Summer 1980). "San Diego Indians and the Federal Government Years of Neglect, 1850-1865". The Journal of San Diego History. San Diego Historical Society. Retrieved 22 June 2010.

Sources

- Field, Margaret (October 2012). "Kumeyaay Language Variation, Group Identity, and The Land". International Journal of American Linguistics . 78 (4): 557–573. doi:10.1086/667451. JSTOR 10.1086/667451. S2CID 147262714.

- Field, Margaret (2017). "Recontextualizing Kumeyaay oral literature for the twenty-first century". In Kroskrity, Paul V.; Meek, Barbra A. (eds.). Engaging Native American Publics: Linguistic Anthropology in a Collaborative Key. Taylor & Francis. pp. 41–59. ISBN 978-1-317-36128-2.

- Gamble, Lynn H.; Zepeda, Irma Carmen (2002). "Social Differentiation and Exchange among the Kumeyaay Indians during the Historic Period in California". Historical Archaeology. 36 (3): 71–91. doi:10.1007/BF03374351. JSTOR 25616993. S2CID 161306672.

- Gamble, Lynn H.; Wilken-Robertson, Michael (2008). "Kumeyaay Cultural Landscapes of Baja California's Tijuana River Watershed". Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology . 28 (2): 127–152. JSTOR 27825888.

- Hoffman, Geralyn Marie; Gamble, Lynn H. (2006). A Teacher's Guide to Historical and Contemporary Kumeyaay Culture (PDF). Institute for Regional Studies of the Californias ,San Diego State University.

- Gray-Kanatiiosh, Barbara A. (2010). Kumeyaay. ABDO Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-617-84911-4.

- Luomala, Katharine (1978). "Tipai-Ipai". In Heizer, Robert F. (ed.). Handbook of North American Indians : California. Volume 8. Smithsonian Institution. pp. 592–609.

- Miller, Amy (2001). A grammar of Jamul Tiipay. Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-110-86482-3.

- O’Neil, Dennish (Summer–Winter 1983). "A Shaman's "Sucking Tube" from San Diego County". California Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology. 5 (1/2): 245–247. JSTOR 27825148.

- Pritzker, Barry (1998). "Tipai-Ipai". Native Americans:Southwest-California-Northwest Coast-Great Basin–Plateau Native Americans: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Peoples. ABC-CLIO. pp. 196–197. ISBN 978-0-874-36836-9.

- Pritzker, Barry; Johansen, Bruce E., eds. (2007). "Tipai-Ipai". Encyclopedia of American Indian History. ABC-CLIO. p. 1071. ISBN 978-1-851-09818-7.

- Sheridan, Thomas E. (Summer 1982). "Seri Bands in Cross-Cultural Perspective". Kiva. 47 (4): 185–213. doi:10.1080/00231940.1982.11760572. JSTOR 30247342.

- Shipek, Florence C. (Winter 1982). "Kumeyaay Socio-Political Structure". Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology . 4 (2): 296–303. JSTOR 27825128.

- Underwood, Jackson (2002–2004). "Pipes and Tobacco Use Among Southern California Yuman Speakers". Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology. 24 (1): 1–12. JSTOR 23799624.

- Van Wormer, Stephen R; Carrico, Richard L. (1993). "Excavation and Analysis of a Stone Enclosure Complex in San Diego County". Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology . 15 (3): 234–246. JSTOR 27825522.

- Waldman, Carl (2014). Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-438-11010-3.

- Erlandson, Jon M.; Rick, Torben C.; Jones, Terry L.; Porcasi, Judith F. (2010), "One If by Land, Two If by Sea: Who Were the First Californians?", in Jones, Terry L.; Klar, Kathryn A. (eds.), California Prehistory: Colonization, Culture, and Complexity, Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press, pp. 53–62, ISBN 978-0-7591-1960-4.

- Hoffman, Geralyn Marie; Gamble, Lynn H. (2006), A Teacher's Guide to Historical and Contemporary Kumeyaay Culture, Institute for Regional Studies of the Californias, San Diego State University.

- Kroeber, A. L. (1925), "Handbook of the Indians of California", Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin, Washington, DC (78).

- Langdon, Margaret (1990), Redden, James E. (ed.), "Diegueño: how many languages?", Proceedings of the 1990 Hokan-Penutian Languages Workshop, University of Southern Illinois, Carbondale: 184–190.

- Luomala, Katharine (1978), "Tipai-Ipai", in Heizer, Robert F. (ed.), Handbook of North American Indians, 8 (California), Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, pp. 592–609, ISBN 0-16004-574-6.

- Pritzker, Barry M. (2000), "Tipai-Ipai", A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 145–147, ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

- Shipek, Florence C. (1978), "History of Southern California Mission Indians", in Heizer, Robert F. (ed.), Handbook of North American Indians, Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution, pp. 610–618, ISBN 0-87474-187-4.

- Shipek, Florence C. (1986), "The Impact of Europeans upon Kumeyaay Culture", in Starr, Raymond (ed.), The Impact of European Exploration and Settlement on Local Native Americans, San Diego: Cabrillo Historical Association, pp. 13–25, OCLC 17346424.

- Smith, Kalim H (2005), Language Ideology and Hegemony in the Kumeyaay Nation: Returning the Linguistic Gaze, University of California, San Diego. Master's Thesis.

Further reading

- Du Bois, Constance Goddard. 1904-1906. "Mythology of the Mission Indians: The Mythology of the Luiseño and Diegueño Indians of Southern California." The Journal of the American Folk-Lore Society, Vol. XVII, No. LXVI. p. 185-8 [1904]; Vol. XIX. No. LXXII pp. 52–60 and LXXIII. pp. 145–64. [1906].

- Miskwish, Michael C. Kumeyaay: A History Book. El Cajon, CA: Sycuan Press, 2007.

- Miskwish, Michael C, and Joel Zwink. Sycuan: Our People, Our Culture, Our History: Honoring the Past, Building the Future. El Cajon, Calif.: Sycuan Band of the Kumeyaay Nation, 2006.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kumeyaay people. |

- Kumeyaay.info: The Kumeyaay Tribes Guide — Tribal Bands of the Kumeyaay Nation (Diegueño) — in San Diego County, California + Baja California state, México

- Kumeyaay Information Village, with educational materials for teachers

- Kumeyaay.com, information website of Larry Banegas, Barona Reservation

- Kumeyaay Indian Language

- Kumeyaay Community College and its *Kumeyaay Studies Program in conjunction with Cuyamaca College

- Kumeyaay Department at Cuyamaca College

- Mythology of the Mission Indians, by Du Bois, 1904-1906.

- Religious Practices of the Diegueño Indians, by T.T. Waterman, 1910.

- Kumeyaay (Diegueño) language overview at the Survey of California and Other Indian Languages

- A.R. Royo, "The Kumeyaay: San Diego County and Baja

- Corpus of Kumiai and Ko’alh spoken in Baja California, Mexico by Margaret Field from the Archive of the Indigenous Languages of Latin America, containing digital audio and hi-definition video from four Baja Kumiai communities: San Jose de la Zorra, La Huerta, Alamo-Neji, Necua and San Jose Tecate

- Kumeyaay Indians of Baja California on YouTube

- Samuel Brown recounts Viejas Reservation - Lesson 1 How to say Kumeyaay on YouTube (2010)