Lạc Việt

The Lạc Việt or Luoyue (駱越 ~ 雒越; pinyin: Luòyuè ← Middle Chinese: *lɑk̚-ɦʉɐt̚ ← Old Chinese *râk-wat[1]) were an ancient conglomeration of Yue tribes that inhabited what is today Guangxi in Southern China and the lowland plains of Northern Vietnam, particularly the marshy, agriculturally rich areas of the Red River Delta.[2] They are the owners of Bronze Age Đông Sơn culture in mainland Southeast Asia[3] and considered to be ancestors of Vietnamese people.[4]

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Vietnam |

|

| Timeline |

|

|

| Lạc Việt | |

|---|---|

| Vietnamese name | |

| Vietnamese | Lạc Việt |

| Hán-Nôm | 駱越 |

Etymology

The ethnonym Lạc's etymology is uncertain. Based on Chinese observers' remarks that the Lạc people's paddies depended on water-control systems like tidal-irrigation & draining, so that the floody, swampy Red River delta might be suitable for agriculture, many scholars opted to find its etymology in the semantic field "water". Japanese scholar Gotō Kimpei links Lạc to Vietnamese noun(s) lạch ~ rạch "ditch, canal, waterway".[5] Vietnamese scholar Vũ Thế Ngọc cites Nguyễn Kim Thản's opinion that Lạc simply means "water" and is comparable to phonetically similar elements in two compounds nước rạc (lit. "ebbing (tidal) water") & cạn rặc (lit. "utterly dried up [of water]")[lower-alpha 1]. Meanwhile, Vũ himself compares Lạc to the common Vietnamese noun nước "water" as well as its Austroasiatic cognates like Stieng đaák, Sedang đák, Churu đạ, Kơho đa, etc. (all from Proto-Austroasiatic *ɗaːk).[7]

Mythology

In Vietnamese mythology, the Lạc, a giant, crane-like bird appeared to the ancient tribes in southern China and guided them through a difficult journey to northern Vietnam. This mysterious bird was later depicted on the elaborate bronze drums from the northern Vietnamese Đông Sơn culture that flourished during the Bronze Age. The Lạc people's ancestors called themselves the Lạc Việt after the bird in its honor.[8]

History

According to legend, the Lạc Việt founded a state called Văn Lang in 2879 BC. Their leaders were called Lạc kings (Hùng kings) who were served by Lạc marquises and Lạc generals.[9] Around the third century BCE, they were defeated by the Âu Việt state of Nam Cương (modern-day Cao Bằng province). In 258 BCE or 257 BCE, Thục Phán, the leader of the alliance of Âu Việt tribes, invaded Văn Lang and defeated the last Hùng king. He united the two kingdoms, naming the new nation Âu Lạc and taking a Sino-Vietnamese title, "peaceful virile king" (Chinese: 安陽王; Vietnamese: An Dương Vương).[10] The leader of the Âu Việt, Thục Phán, dethroned the last Hung kings, imposed his authority over the Lac lords then took the title of King An Dương and established the kingdom of Âu Lạc.[11] According to the Records of the Grand Historian by Sima Qian, Âu Lạc was referred as the "Western Ou" (v. Tây Âu) and "Luo" (v. Lạc) and they were lumped into the category of Baiyue by the Sinitic peoples to the north.[12][13] The new Âu overlords established their headquarters in Tây Vu, where they built a large citadel, known to history as Cổ Loa or Cổ Loa Thành, “Old Snail City”.[14]

They were in the transformation from bronze age to iron age, skilled at cultivating rice, keeping water buffalos and pigs, fishing and sailing in long dugout canoes. They also were skilled bronze casters, which is evidenced by the Dong Son drum found widely throughout northern Vietnam, and South China. Lạc's customs were seen as unorthodox and barbaric to the Chinese, but similar to the Baiyue.[15] In 111 BC, the Western Han dynasty conquered Nanyue and incorporated the Lac Viet land into their empire, established the Jiaozhi, Jiuzhen and later Rinan commanderies in modern-day Vietnam. After gaining a briefly independence amid the Trung sisters' rebellion, the Lac chiefs and elites were massacred, deported and forced to adopt Han cultures by the Chinese reconquer Ma Yuan.[16] Later, Chinese historians writing of Ma Yuan’s expedition referred to the ancient Vietnamese as the “Lac Yüeh” or simply as the “Yuè”.[17]

Conversion to Buddhism

During the early phase of the Three Kingdoms era, a unrest raged across the Jiaozhi circuit (modern-day Guangdong, Guangxi and northern Vietnam) led by the Wuhu chief Liang Long and his rebellion attracted the Lac Viet and all other ethnic groups in Southern Han China, but was suppressed in 184.[18] After a century and a half of close imperial supervision and repression, Jiaozhi and Jiuzhen enjoyed a period of autonomy from 187 to 226. In 177 Shi Xie became the prefect of Jiaozhi (Jiaozhou (modern Vietnam and Guangzhou)), is primarily remembered today in Vietnam as Sĩ Nhiếp, the father of education and a great patron of Buddhism. He relocated Jiaozhi’s capital back to Luy Lâu, the river market town Zhào Tuó had founded in 179 BC, which soon became celebrated for its trading prosperity. Shi Xie stayed out of the northern wars for the most part and later willingly submitted to Eastern Wu. Buddhism became the predominant religion the Lac people.[19] In 255–56, a Lac monk Đạo Thanh coauthored one of the first translations of the Mahayana sutra entitled The Saddharmapandarika (V. Pháp Hoa Tam Muội), or Lotus of Good Faith.[20] During Shi Xie's reign, the Lac people's customs had been slightly altered and sinicized by Xie.[21]

The south’s trade and treasure attracted imperial power. After Shi Xie’s death in 226, the Wu court at Nanjing reasserted direct Chinese control over Jiaozhi. An army of three thousand set out from Nanhai Commandery and sailed up the Red River. The Wu general summoned Xie’s son, Shi Hui, with his five brothers and sons, and beheaded them all.[22] Having conquered Jiaozhi, Wu forces also stormed Jiuzhen, killing or capturing ten thousand people, along with surviving members of Shi Xie’s family In 231, the Wu court had to send another general to Jiuzhen to “exterminate and pacify the barbarous Yuè” there.[22] In 248, the people of Jiaozhi and Jiuzhen commanderies rebelled. A Lạc Việt woman named Triệu Ẩu in Jiuzhen led a rebellion, followed by a hundred Lac chieftains led fifty thousand families in her revolt.[23] Eastern Wu sent Lu Yin to deal with the rebels. He defeated her and put her to death.[24][25]

In 263, Lac Viet people in Jiaozhi and Jiuzhen under Lã Hưng one again revolted against the Wu dynasty. The rebels handed the region over to Wu’s rival, the northern Chinese kingdom of Jin.[24] In 268 and 269, they held off large Wu armies and fleets, which eventually retook Jiaozhi’s ports and main towns in 271. Fighting continued in the countryside until 280, when Jin destroyed Wu, reunifying China.[24]

Culture and society

Lạc lords were hereditary aristocrats in something like a feudal system. The status of Lạc lords passed through the family line of one’s mother and tribute was obtained from communities of agriculturalists who practiced group responsibility. In Lạc society, access to land was based on communal usage rather than individual ownership and women possessed inheritance rights. While in Chinese society men inherited wealth through their fathers, in Lạc society both men and women inherited wealth through their mothers.[26]

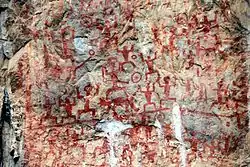

According to Linh Nam chich quai, the Duke of Zhou said to the envoys, “Why do you people from Jiaozhi have short hair, tattoo your bodies, and go bareheaded and barefooted?” The author of Linh Nam chich quai expressed cultural pride through the mouths of envoys to the Zhou court: “Short hair is for convenience when traveling through the mountains and forests. We tattoo our bodies to look like dragons, so when we travel through the water the flood dragon will not dare to attack us. We go barefoot for convenience when climbing trees. We engage in slash and burn agriculture [and leave our heads bare] to beat the heat. We chew betel to get rid of filth, and therefore our teeth become black.”[27]

Ancient Han Chinese had described the people of Âu Lạc as barbaric,[15] comparing their language to animal shrieking and had regarded them as lacking morals and modesty. However, the egalitarian nature of their society, the comparatively high status of women, the practice of getting married without a matchmaker and indeed consulting the wishes of the couple concerned, all now seem enlightened rather than barbaric.[28]

A Chinese text dating from the 220s BCE reporting "unorthodox customs" of the Yue in a part of the Lạc Việt region states:“To crop the hair, decorate the body, rub pigment into arms and fasten garments on the left side is the way of the Bakviet. In the country of Tai-wu (Vietnamese: Tây Vu) the habit is to blacken teeth, scar cheeks and wear caps of sheat [catfish] skin stitched crudely with an awl.”[29]

According to Hou Hanshu, the whole territory of the Âu Lạc people is covered with dense forests, ponds and lakes. There are a lot of wild animals like elephants, rhinoceros and tigers. The natives earn their living by hunting and fishing. They eat the meat of boa constrictors, snakes and wild animals which they kill with bows propelling bone-headed arrows....In fighting, they use bows propelling poisoned arrows. The process of making poison for arrows is a secret which they swear never to disclose to anyone. They know how to cast copper implements and pointed arrowheads. The natives tattoo themselves, wear chignon and turbans. They chew betel nuts and blacken their teeth.[30]

Chinese writers noted the Yue preoccupation with aquatic life. One text, the Huainanzi, stated in 135 BCE that in Nanyue, which then included the Red River Delta, “people carry out few occupations on land and many on water.” The inhabitants even cut their hair and “tattoo their bodies in order to resemble the scaly-skinned aquatic animals.”[31]

Lạc Việt people organized themselves along less strict, nonnuclear lines, giving authority to women as well as men. They formed matrilocal clans: couples after marriage would often go to live with the wife’s family. This matrilocal custom kept sisters together and gave married women key roles in social communication, and some were regarded as at least the equals of men. [32] Unmarried couples often lived together. This relatively open family structure contrasted with most of Chinese society, which was based increasingly though not solely on Confucian notions of the patriarchal family, in particular “filial piety,” which also provided a model for imperial government.[33] In addition, they also practiced levirate.[34][35] This meant that childless widows had a right to bear children with men from their deceased husbands’ families in order to obtain heirs. This practice ostensibly provided an heir for the mother, although some patriarchal societies used it to provide an heir for the deceased father.[26] If the levirate was an innovation designed to keep land holdings in the same male family, it also reflected an earlier tradition of female authority and protection of widows’ interests.[34] Linguistic vestiges of female status corroborate this view. Huỳnh Sanh Thông identified no fewer than thirty-two Vietnamese words for “mother” or “woman,” including seven archaic and twelve modern terms for “mother.” These also carry important other meanings, involving fertility, water, agriculture, and bronze drums. The words for water (nác/nước) and “country” (nước) derive from one of the archaic Vietnamese terms for woman (nàng), while another, nương, is also used to describe an upland field or swidden. Of two Vietnamese words for “witch, female medium,” one (bóng) also means a type of drum. The other (đồng), a homonym for both “bronze” and “a field in the country,” combines with an archaic term for “mother” (áng) to form đồng áng (“ricefields; the countryside”). All this suggests a possible Earth Mother cult and rituals associating water and fertility with bronze drums and female shamans.[36]

Women also remained prominent in indigenous religious rites, including water rituals. Local worship of the Chư vị, or Spirits of the Three Worlds—Heaven, Earth, and Water—was still popular. Most of the priests or spirit mediums involved in this were women.[37]

During the Han dynasty, the Lạc people of Jiaozhi often traded rice for pearls with the people of Hepu while the Lạc tribe in Jiuzhen mainly made their living by hunting and gathering. People often had to buy rice from Jiaozhi.[38] Silk was also a prized commodity of the Lac people, which the capital of Jiaozhi, Luy Lâu, derived its name from the Vietnamese word for mulberry (dâu) and Proto-Vietic (-to) and it housed the most ancient Buddhist temple in Vietnam, the Dâu Temple, whose name also derived from dâu.[39]

See also

Notes

- Hồ Ngọc Đức's Free Vietnamese Dictionary Project glosses rặc as "means tidal water when falling"[6]

References

- Schuessler, Axel. (2007) An Etymological Dictionary of Old Chinese. University of Hawaii Press. p. 372

- SarDesai, D. R. (1998). Vietnam, Past and Present. Avalon Publishing. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-8133-3435-6.

- Hoàng, Anh Tuấn (2007). Silk for Silver: Dutch-Vietnamese Rerlations ; 1637 - 1700. BRILL. p. 12. ISBN 978-90-04-15601-2.

- Ferlus, Michel (2009). "A Layer of Dongsonian Vocabulary in Vietnamese". Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society. 1: 105.

- Taylor 1983, p. 10.

- "rặc". Hồ Ngọc Đức's Vietnamese dictionary (in Vietnamese).

- Vũ, Thế Ngọc. (1989) "The Meaning of the National Name Lạc Việt". Đặc San Đền Hùng (in Vietnamese)

- "Lạc Việt: The Myth of Vietnam's Forbidden Kingdom". theculturetrip.

- Kelley 2014, p. 88.

- Chapuis 1995, p. 13.

- Taylor 1983, p. 19.

- Brindley 2015, p. 31.

- Wu & Rolett 2019, p. 28.

- Taylor 1983, p. 21.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 71.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 81.

- Taylor 1983, p. 33.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 87-89.

- Li & Anderson 2011, p. 9.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 93.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 91-92.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 91.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 97-98.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 98.

- Taylor 1983, p. 70.

- Taylor 2013, p. 20.

- Baldanza 2016, pp. 43-44.

- Milburn 2010, p. 31.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 61.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 73.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 63.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 75.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 74.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 51.

- De Vos & Slote 1998, p. 91.

- Kiernan 2019, pp. 51-52.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 92.

- Li 2011, p. 42.

- Li 2011, p. 44.

Bibliography

- Watson, Burton (1961). Records Of The Grand Historian Of China. Columbia University Press.

- Leeming, David (2001). A Dictionary of Asian Mythology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195120523.

- Kiernan, Ben (2019). Việt Nam: a history from earliest time to the present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-190-05379-6.

- Taylor, Keith Weller (1983). The Birth of the Vietnam. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07417-0.

- Taylor, Keith Weller (2013). A History of the Vietnamese. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521875868.

- SarDesai, D. R. (2005). Vietnam, Past and Present. Avalon Publishing. ISBN 9780813343082.

- Loewe, Michael (1986), "The Former Han dynasty", in Twitchett, Denis C.; Fairbank, John King (eds.), The Cambridge History of China: Volume 1, The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC-AD 220, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 110–128, ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8

- Yü, Ying-shih (1986). "Han Foreign Relations". In Twitchett, Dennis; Loewe, Michael (eds.). The Cambridge History of China, Volume 1: The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC–AD 220. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24327-8.

- Brindley, Erica (2015). Ancient China and the Yue: Perceptions and Identities on the Southern Frontier, C.400 BCE-50 CE. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1107084784.

- Higham, Charles (1996). The Bronze Age of Southeast Asia. Cambridge World Archaeology. ISBN 0-521-56505-7.

- Wu, Chunming; Rolett, Barry Vladimir (2019). Prehistoric Maritime Cultures and Seafaring in East Asia. Springer Singapore. ISBN 9813292563.

- Li, Tana (2011), "Jiaozhi (Giao Chỉ) in the Han Period Tongking Gulf", in Li, Tana; Anderson, James A. (eds.), The Tongking Gulf Through History, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 39–53, ISBN 978-0-812-20502-2

- Hoàng, Anh Tuấn (2007). Silk for Silver: Dutch-Vietnamese Rerlations ; 1637 - 1700. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-15601-2.

- Dutton, George; Werner, Jayne; Whitmore, John K., eds. (2012). Sources of Vietnamese Tradition. Introduction to Asian Civilizations. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13862-8.

- De Vos, George A.; Slote, Walter H., eds. (1998). Confucianism and the Family. State University of New York Press. ISBN 9780791437353.

- Kelley, Liam C. (2014), "Constructing Local Narratives: Spirits, Dreams, and Prophecies in the Medieval Red River Delta", in Anderson, James A.; Whitmore, John K. (eds.), China's Encounters on the South and Southwest: Reforging the Fiery Frontier Over Two Millennia, United States: Brills, pp. 78–106, ISBN 978-9-004-28248-3

- Sharma, S. D. (2010). Rice: Origin, Antiquity and History. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-57808-680-1.

- Brindley, Erica F. (2015). Ancient China and the Yue. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-08478-0.

- Him, Mark Lai; Hsu, Madeline (2004). Becoming Chinese American: A History of Communities and Institutions. AltaMira Press. ISBN 978-0-759-10458-7.

- Lim, Ivy Maria (2010). Lineage Society on the Southeastern Coast of China. Cambria Press. ISBN 978-1604977271.

- Peters, Heather (April 1990). H. Mair, Victor (ed.). "Tattooed Faces and Stilt Houses: Who were the Ancient Yue?" (PDF). Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations, University of Pennsylvania. East Asian Collection. Sino-Platonic Papers. 17.

- Marks, Robert B. (2017). China: An Environmental History. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-442-27789-2.

- Milburn, Olivia (2010). The Glory of Yue: An Annotated Translation of the Yuejue shu. Sinica Leidensia. 93. Brill Publishers.

- Lu, Yongxiang (2016). A History of Chinese Science and Technology. Springer. ISBN 978-3-662-51388-0.

- Ngô Sĩ Liên, Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư (in Vietnamese)

- Đào Duy Anh (1959). Lịch sử Cổ đại Việt Nam [越南古代史]. Translated by 刘统文; 子钺. China Science Publishing & Media.

- Chapuis, Oscar (1995). A History of Vietnam: From Hong Bang to Tu Duc. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-29622-2.