Jiaozhou (region)

Jiaozhou (Chinese: 交州; Wade–Giles: Chiao1-Cho1; Vietnamese: Giao Châu) was an imperial Chinese province under the Han and Jin dynasties. Under the Han, the area included Liangguang and northern Vietnam but Guangdong was later separated to form the province of Guangzhou by Sun Quan following the death of Shi Xie and lasted until the creation of Protectorate General to Pacify the South in 679.

| Jiaozhou | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 交州 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 交州 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||

| Vietnamese | Giao Châu | ||||||||

| Hán-Nôm | 交州 | ||||||||

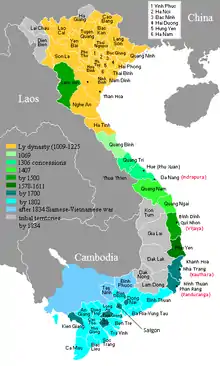

| History of Vietnam (Names of Vietnam) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

History

Han dynasty

In 111 BC, the armies of Emperor Wu conquered the rebel state of Nanyue and organized the area as the circuit (部 bù) of Jiāozhǐ, under the rule of a cìshǐ (zh:刺史, vi:thứ sử). In addition to six original commanderies (Nanhai, Hepu, Cangwu, Yulin, Jiaozhi and Jiuzhen), the Han Empire conquered new territories on Hainan as well as in the area south of the Ngang Pass and established them as the commanderies of Zhuya, Dan'er, and Rinan.[1] In 203 CE, Jiāozhǐ bù was renamed to Jiāozhōu.

Eastern Wu

Following the death of Shi Xie in 226 CE, Eastern Wu divided Jiaozhou into Guangzhou and the new Jiaozhou. However, after suppressing Shi Hui (士徽), son of Shi Xie, Eastern Wu re-annexed Guangzhou into Jiaozhou. It was only in 264 CE that Jiaozhou was re-divided: Guangzhou was composed of three commanderies of Nanhai, Cangwu and Yulin while the new Jiaozhou was composed of four commanderies of Hepu, Jiaozhi, Jiuzhen and Rinan. Also in the same year, a Roman envoy arrived in Jiaozhi of Jiaozhou and was hastened to the Wu court. In 229, Eastern Wu sent embassy to Funan, where merchants from India and beyond gathered.[2]

The Wu regime was harsh. Turmoil plagued the southern commanderies by the mid third century. In 231, Lac Viet people in Jiuzhen revolted but was "pacified" by a Wu general.[2] In 248, Lâm Ấp forces invaded from the south, seized most of Rinan, and marched on into Jiuzhen, provoking major uprisings there and in Jiaozhi. One Jiaozhi rebel commanded thousands and invested several walled towns before Wu officials got him to surrender.[3]

In Jiuzhen, a Lạc Việt woman named Triệu Ẩu (Lady Triệu) led a rebellion against the Wu in 248, but was suppressed by Lu Yin.[4]

In 263, "Yue barbarians" in Jiaozhi and Jiuzhen under Lã Hưng revolted against the Wu dynasty. The rebels handed the region over to Wu’s rival, the northern Chinese kingdom of Jin.[4] In 268 and 269, they held off large Wu armies and fleets, which eventually retook Jiaozhi’s ports and main towns in 271. Fighting continued in the countryside until 280, when Jin destroyed Wu, reunifying China.[4]

Jin dynasty

In the early period of Jin dynasty, the imperial court favored the southern trade networks with prosperity kingdoms of Funan and Lâm Ấp. Along with this brief peacetime “boom” in the southern trade, Jiaozhi and Jiuzhen enjoyed some autonomy from China until the 320s.[4] In 312 rebels and imperial units fought each other with ferocity over Jiaozhi and Jiuzhen. Frustrated by the difficulty of trade, Lâm Ấp itself resorted from 323 to seaborne raids on northern ports in Jiaozhou.[4] Though defeated in 399, Lâm Ấp continued its raids on Jiaozhi and Jiuzhen for two decades.[5] A Chinese rebel army from Zhejiang briefly seized Jiaozhi’s capital in 411.[5]

During the Jin dynasty and Six dynasties period of China, the Li-Lao people extended their territories right along the south coast of modern Guangdong and Guangxi, in a swath of land to the east of the Red River Delta and south and west of the Pearl River Delta, occupied the overland roads between Guangzhou and Jiaozhou.[6] The people of Li-Lao country put anyone traveled through their territories in dangers.[7]

Southern dynasties

In 446, Liu Song dynasty invaded Lâm Ấp, captured Lâm Ấp's capital (near modern Huế). The Chinese attackers plundered its eight temples and treasury, carrying off 100,000 pounds of gold.[5] Despite that, the revived Lâm Ấp was flourishing on the ever more lucrative passing sea trade.[5]

Rebellions broke out in Jiaozhou from 468 to 485, and in 506 and 515 under Liang dynasty.[5]

In 541, Lý Bôn, a leader of the local Li clan which had Sinitic ancestry, revolted against the Liang. In 544 he defeated the Liang and proclaimed himself Emperor of Nán Yuè with reign era Thiên-đức.[8] Jiaozhou briefly became independence from the Chinese dynasties. In 545, Chen Baxian led the Liang army attack Jiaozhou, forced Lý Bôn fled west into the mountains above the Red River, where he was killed by Lao highlanders in 548.[9] However even after Lý Bôn's death, Jiaozhou remained autonomous.[10] In 583, Lý Hữu Vinh, a local leader of Jiaozhou sent a trained elephant to the Chen court.[11]

Sui Dynasty

Around 589-590 Lý Xuân (Lý Phật Tử) became the leader of the autonomous Jiaozhou. As the authority of Sui gradually consolidated in Kwangsi and Kwangdong, Lý Phật Tử recognized Sui over lordship.[12] In 601, governor of Guangzhou, Ling-hu Hsi forwarded an imperial summons for Phật Tử to appear at the Sui capital. Resolved to resist this demand, Phật Tử sought delay by requesting that the summons be postponed until after the new year. Hsi approved the request, believing that he could keep Phật Tử’s allegiance by exercising restraint. Someone, however, accused Hsi of taking a bribe from Phật Tử, and the court grew suspicious. When Phật Tử openly rebelled early in 602, Hsi was promptly arrested; he died en route north.[13] This caused the Sui court called general Liu Fang to command 27,000 troops attacked Lý Phật Tử from Yunnan in 602. At Đỗ Long Pass, on the watershed between the Hsi and Chảy Rivers, Fang met two thousand of Phật Tử’s men. Brushing aside this unsuspecting frontier garrison, Fang descended the Chay River and penetrated into the heart of Phật Tử’s realm. Unprepared to resist an assault from such an unexpected quarter, Phật Tử heeded Fang’s admonition to surrender and was sent to the Sui capital at Chang'an. Lý Phật Tử and his subordinates were beheaded to preclude future trouble.[14] This marked the Third Chinese domination of Vietnam.

Tang dynasty

In 622, Xiao Xian was defeated by the Tang and the Chinese warlord in Jiaozhou Ch'iu Ho submitted to the Tang dynasty.[15]

In 679, Protectorate General to Pacify the South was created and replaced the Jiaozhou protectorate.[16]

See also

References

- Ban Biao; Ban Gu; Ban Zhao. "地理志" [Treatise on geography]. Book of Han (in Chinese). Volume 28. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- Taylor 1983, p. 89.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 97.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 98.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 99.

- Churchman 2011, p. 67-68.

- Churchman 2011, p. 71-74.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 102.

- Kiernan 2019, p. 103.

- Taylor 1983, p. 158.

- Taylor 1983, p. 157.

- Taylor 1983, p. 159.

- Taylor 1983, p. 161.

- Taylor 1983, p. 162.

- Taylor 1983, p. 169.

- Taylor 1983, p. 171.

Sources

- Taylor, Keith Weller (1983). The Birth of the Vietnam. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07417-0.

- Kiernan, Ben (2019). Việt Nam: a history from earliest time to the present. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190053796.

- Loewe, Michael (1986), "The conduct of government and the issues at stake (A.D. 57-167)", in Twitchett, Denis C.; Fairbank, John King (eds.), The Cambridge History of China: Volume 1, The Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 BC-AD 220, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 291–316

- Li, Tana (2011), "Jiaozhi (Giao Chỉ) in the Han Period Tongking Gulf", in Li, Tana; Anderson, James A. (eds.), The Tongking Gulf Through History, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 39–53, ISBN 978-0-812-20502-2

- Churchman, Michael (2011), ""The People in Between": The Li and the Lao from the Han to the Sui", in Li, Tana; Anderson, James A. (eds.), The Tongking Gulf Through History, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, pp. 67–86, ISBN 978-0-812-20502-2