Paddy field

A paddy field is a flooded field of arable land used for growing semiaquatic crops, most notably rice and taro. It originates from the Neolithic rice-farming cultures of the Yangtze River basin in southern China, associated with pre-Austronesian and Hmong-Mien cultures. It was spread in prehistoric times by the Austronesian expansion to Island Southeast Asia, Southeast Asia including Northeastern India, Madagascar, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. The technology was also acquired by other cultures in mainland Asia for rice farming, spreading to East Asia, Mainland Southeast Asia, and South Asia.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Fields can be built into steep hillsides as terraces and adjacent to depressed or steeply sloped features such as rivers or marshes. They can require a great deal of labor and materials to create and need large quantities of water for irrigation. Oxen and water buffalo, adapted for life in wetlands, are important working animals used extensively in paddy field farming.

Paddy-field farming remains the dominant form of growing rice in modern times. It is practiced extensively in Bangladesh, Cambodia, China, Northeastern India, Indonesia, Iran, Japan, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Nepal, North Korea, Pakistan, the Philippines, South Korea, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Taiwan, and Vietnam.[1] It has also been introduced elsewhere since the colonial era, notably in Northern Italy, the Camargue in France,[2] and in Spain, particularly in the Albufera de València wetlands in the Valencian Community, the Ebro Delta in Catalonia and the Guadalquivir wetlands in Andalusia, as well as along the eastern coast of Brazil, the Artibonite Valley in Haiti, and Sacramento Valley in California, among other places. Paddy fields are a major source of atmospheric methane and have been estimated to contribute in the range of 50 to 100 million tonnes of the gas per annum.[3][4] Studies have shown that this can be significantly reduced while also boosting crop yield by draining the paddies to allow the soil to aerate to interrupt methane production.[5] Studies have also shown the variability in assessment of methane emission using local, regional and global factors and calling for better inventorisation based on micro level data.[6]

Paddy cultivation should not be confused with cultivation of deepwater rice, which is grown in flooded conditions with water more than 50 cm (20 in) deep for at least a month.

Etymology

The word "paddy" is derived from the Malay word padi, meaning "rice plant".[7] It is derived from Proto-Austronesian *pajay ("rice in the field", "rice plant"), with cognates including Amis panay; Tagalog paláy; Kadazan Dusun paai; Javanese pari; and Chamorro faʻi, among others.[8]

History

Neolithic southern China

(8500 to 1500 BC)

Genetic evidence shows that all forms of paddy rice, both indica and japonica, spring from a domestication of the wild rice Oryza rufipogon by cultures associated with pre-Austronesian and Hmong-Mien-speakers. This occurred around 13,500 to 8,200 years ago south of the Yangtze River in present-day China.[9][10]

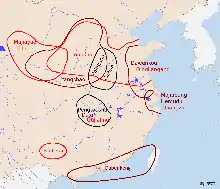

There are two most likely centers of domestication for rice as well as the development of the wet-field technology. The first, and most likely, is in the lower Yangtze River, believed to be the homelands of the pre-Austronesians and possibly also the Kra-Dai, and associated with the Kuahuqiao, Hemudu, Majiabang, Songze, Liangzhu, and Maquiao cultures.[11][12][13][14][15] The second is in the middle Yangtze River, believed to be the homelands of the early Hmong-Mien-speakers and associated with the Pengtoushan, Nanmuyuan, Liulinxi, Daxi, Qujialing, and Shijiahe cultures. Both of these regions were heavily populated and had regular trade contacts with each other, as well as with early Austroasiatic speakers to the west, and early Kra-Dai speakers to the south, facilitating the spread of rice cultivation throughout southern China.[12][13][15]

The earliest paddy field found dates to 4330 BC, based on carbon dating of grains of rice and soil organic matter found at the Chaodun site in Kunshan County.[16][17] At Caoxieshan, a site of the Neolithic Majiabang culture, archaeologists excavated paddy fields.[18] Some archaeologists claim that Caoxieshan may date to 4000–3000 BC.[19][20] There is archaeological evidence that unhusked rice was stored for the military and for burial with the deceased from the Neolithic period to the Han Dynasty in China.[21]

By the late Neolithic (3500 to 2500 BC), population in the rice cultivating centers had increased rapidly, centered around the Qujialing-Shijiahe culture and the Liangzhu culture. There was also evidence of intensive rice cultivation in paddy fields as well as increasingly sophisticated material cultures in these two regions. The number of settlements among the Yangtze cultures and their sizes increased, leading some archeologists to characterize them as true states, with clearly advanced socio-political structures. However, it is unknown if they had centralized control.[22][23]

Liangzhu and Shijiahe declined abruptly in the terminal Neolithic (2500 to 2000 BC). With Shijiahe shrinking in size, and Liangzhu disappearing altogether. This is largely believed to be the result of the southward expansion of the early Sino-Tibetan Longshan culture. Fortifications like walls (as well as extensive moats in Liangzhu cities) are common features in settlements during this period, indicating widespread conflict. This period also coincides with the southward movement of rice-farming cultures to the Lingnan and Fujian regions, as well as the southward migrations of the Austronesian, Kra-Dai, and Austroasiatic-speaking peoples to Mainland Southeast Asia and Island Southeast Asia.[22][24][25]

Austronesian expansion

.png.webp)

(3500 BC to AD 1200)

.png.webp)

The spread of japonica rice cultivation and paddy field agriculture to Southeast Asia started with the migrations of the Austronesian Dapenkeng culture into Taiwan between 3500 and 2000 BC (5,500 BP to 4,000 BP). The Nanguanli site in Taiwan, dated to ca. 2800 BC, has yielded numerous carbonized remains of both rice and millet in waterlogged conditions, indicating intensive wetland rice cultivation and dryland millet cultivation.[13]

From about 2000 to 1500 BC, the Austronesian expansion began, with settlers from Taiwan moving south to colonize Luzon in the Philippines, bringing rice cultivation technologies with them. From Luzon, Austronesians rapidly colonized the rest of Island Southeast Asia, moving westwards to Borneo, the Malay Peninsula and Sumatra; and southwards to Sulawesi and Java. By 500 BC, there is evidence of intensive wetland rice agriculture already established in Java and Bali, especially near very fertile volcanic islands.[13]

Rice did not survive the Austronesian voyages into Micronesia and Polynesia, however wet-field agriculture was transferred to the cultivation of other crops, most notably for taro cultivation. The Austronesian Lapita culture also came into contact with the non-Austronesian (Papuan) early agriculturists of New Guinea and introduced wetland farming techniques to them. In turn, they assimilated their range of indigenous cultivated fruits and tubers before spreading further eastward to Island Melanesia and Polynesia.[13]

Rice and wet-field agriculture were also introduced to Madagascar, the Comoros, and the coast of East Africa by around the 1st millennium AD by Austronesian settlers from the Greater Sunda Islands.[26]

Korea

There are ten archaeologically excavated rice paddy fields in Korea. The two oldest are the Okhyun and Yaumdong sites, found in Ulsan, dating to the early Mumun pottery period.[27]

Paddy field farming goes back thousands of years in Korea. A pit-house at the Daecheon-ni site yielded carbonized rice grains and radiocarbon dates, indicating that rice cultivation in dry-fields may have begun as early as the Middle Jeulmun pottery period (c. 3500–2000 BC) in the Korean Peninsula.[28] Ancient paddy fields have been carefully unearthed in Korea by institutes such as Kyungnam University Museum (KUM) of Masan. They excavated paddy field features at the Geumcheon-ni Site near Miryang, South Gyeongsang Province. The paddy field feature was found next to a pit-house that is dated to the latter part of the Early Mumun pottery period (c. 1100–850 BC). KUM has conducted excavations, that have revealed similarly dated paddy field features, at Yaeum-dong and Okhyeon, in modern-day Ulsan.[29]

The earliest Mumun features were usually located in low-lying narrow gullies, that were naturally swampy and fed by the local stream system. Some Mumun paddy fields in flat areas were made of a series of squares and rectangles, separated by bunds approximately 10 cm in height, while terraced paddy fields consisted of long irregular shapes that followed natural contours of the land at various levels.[30][31]

Mumun Period rice farmers used all of the elements that are present in today's paddy fields, such as terracing, bunds, canals, and small reservoirs. We can grasp some paddy-field farming techniques of the Middle Mumun (c. 850–550 BC), from the well-preserved wooden tools excavated from archaeological rice fields at the Majeon-ni Site. However, iron tools for paddy-field farming were not introduced until sometime after 200 BC. The spatial scale of paddy-fields increased, with the regular use of iron tools, in the Three Kingdoms of Korea Period (c. AD 300/400-668).

Japan

The first paddy fields in Japan date to the Early Yayoi period (300 BC – 250 AD).[32] The Early Yayoi has been re-dated, and it appears that wet-field agriculture developed at about the same time as in the Korean peninsula.

Culture

| China | 204.3 |

| India | 152.6 |

| Indonesia | 69.0 |

| Vietnam | 43.7 |

| Thailand | 37.8 |

| Bangladesh | 33.9 |

| Myanmar | 33.0 |

| Philippines | 18.0 |

| Brazil | 11.5 |

| Japan | 10.7 |

| Pakistan | 9.4 |

| Cambodia | 9.3 |

| United States | 9.0 |

| Korea | 6.4 |

| Egypt | 5.9 |

| Nepal | 5.1 |

| Nigeria | 4.8 |

| Madagascar | 4.0 |

| Sri Lanka | 3.8 |

| Laos | 3.5 |

| Source: Food and Agriculture Organization | |

China

Although China's agricultural output is the largest in the world, only about 15% of its total land area can be cultivated. About 75% of the cultivated area is used for food crops. Rice is China's most important crop, raised on about 25% of the cultivated area. Most rice is grown south of the Huai River, in the Yangtze valley, the Zhu Jiang delta, and in Yunnan, Guizhou, and Sichuan provinces.

Rice appears to have been used by the Early Neolithic populations of Lijiacun and Yunchanyan in China.[34] Evidence of possible rice cultivation from ca. 11,500 BP has been found, however it is still questioned whether the rice was indeed being cultivated, or instead being gathered as wild rice.[35] Bruce Smith, an archaeologist at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., who has written on the origins of agriculture, says that evidence has been mounting that the Yangtze was probably the site of the earliest rice cultivation.[36] In 1998, Crawford & Shen reported that the earliest of 14 AMS or radiocarbon dates on rice from at least nine Early to Middle Neolithic sites is no older than 7000 BC, that rice from the Hemudu and Luojiajiao sites indicates that rice domestication likely began before 5000 BC, but that most sites in China from which rice remains have been recovered are younger than 5000 BC.[34]

During the Spring and Autumn period (722–481 BC), two revolutionary improvements in farming technology took place. One was the use of cast iron tools and beasts of burden to pull plows, and the other was the large-scale harnessing of rivers and development of water conservation projects. Sunshu Ao of the 6th century BC and Ximen Bao of the 5th century BC are two of the earliest hydraulic engineers from China, and their works were focused upon improving irrigation systems.[37] These developments were widely spread during the ensuing Warring States period (403–221 BC), culminating in the enormous Du Jiang Yan Irrigation System engineered by Li Bing by 256 BC for the State of Qin in ancient Sichuan. During the Eastern Jin (317–420) and the Northern and Southern Dynasties (420–589), land-use became more intensive and efficient, rice was grown twice a year and cattle began to be used for plowing and fertilization.

In circa 750, 75% of China's population lived north of the river Yangtze, but by 1250, 75% of China's population lived south of the river Yangtze. Such large-scale internal migration was possible due to introduction of quick-ripening strains of rice from Vietnam suitable for multi-cropping.[38]

Localities in China which are famous for their spectacular rice paddies are Yuanyang County, Yunnan, and Longsheng County, Guangxi.

India

India has the largest paddy output in the world and is also the fourth largest exporter of rice in the world. In India, West Bengal is the largest rice producing state.[39] Paddy fields are a common sight throughout India, both in the northern gangetic plains and the southern peninsular plateaus. Paddy is cultivated at least twice a year in most parts of India, the two seasons being known as Rabi and Kharif respectively. The former cultivation is dependent on irrigation, while the latter depends on Monsoon. The paddy cultivation plays a major role in socio-cultural life of rural India. Many festivals such as Onam in Kerala, Bihu in Assam, Makara Sankranthi in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, Thai Pongal In Tamil Nadu, Makar Sankranti in Karnataka, Nabanna in West Bengal celebrates harvest of Paddy. Kaveri delta region of Thanjavur is historically known as the rice bowl of Tamil Nadu and Kuttanadu is called the rice bowl of Kerala.Gangavathi is known as rice bowl of karnataka

Indonesia

Prime Javanese paddy yields roughly 6 metric tons of unmilled rice (2.5 metric tons of milled rice) per hectare. When irrigation is available, rice farmers typically plant Green Revolution rice varieties allowing three growing seasons per year. Since fertilizer and pesticide are relatively expensive inputs, farmers typically plant seeds in a very small plot. Three weeks following germination, the 15-20 centimetre (6–8 in) stalks are picked and replanted at greater separation, in a backbreaking manual procedure.

Rice harvesting in Central Java is often performed not by owners or sharecroppers of paddy, but rather by itinerant middlemen, whose small firms specialize in harvesting, transport, milling, and distribution to markets.

The fertile volcanic soil of much of the Indonesian archipelago—and particularly the islands of Java and Bali—has made rice a central dietary staple. Steep terrain on Bali resulted in an intricate cooperation systems, locally called subak, to manage water storage and drainage for rice terraces.[40]

Italy

Rice is grown in northern Italy, especially in the valley of the river Po.[41] The paddy fields are irrigated by fast-flowing streams descending from the Alps.

Japan

The acidic soil conditions common in Japan due to volcanic eruptions have made the paddy field the most productive farming method. Paddy fields are represented by the kanji 田 (commonly read as ta or as den) that has had a strong influence on Japanese culture. In fact, the character 田, which originally meant 'field' in general, is used in Japan exclusively to convey the meaning 'rice paddy field'. One of the oldest samples of writing in Japan is widely credited to the kanji 田 found on pottery at the archaeological site of Matsutaka in Mie Prefecture that dates to the late 2nd century.

Ta (田) is used as a part of many place names as well as in many family names. Most of these places are somehow related to the paddy field and, in many cases, are based on the history of a particular location. For example, where a river runs through a village, the place east of river may be called Higashida (東田), literally "east paddy field." A place with a newly irrigated paddy field, especially those during or later than Edo period, may be called Nitta or Shinden (both 新田), "new paddy field." In some places, lakes and marshes were likened to a paddy field and were named with ta, like Hakkōda (八甲田).

Today, many family names have ta as a component, a practice which can be largely attributed to a government edict in the early Meiji Period which required all citizens to have a family name. Many chose a name based on some geographical feature associated with their residence or occupation, and as nearly three-fourths of the population were farmers, many made family names using ta. Some common examples are Tanaka (田中), literally meaning "in the paddy field;" Nakata (中田), "middle paddy field;" Kawada (川田), "river paddy field;" and Furuta (古田), "old paddy field."

In recent years, rice consumption in Japan has fallen and many rice farmers are increasingly elderly. The government has subsidized rice production since the 1970s, and favors protectionist policies regarding cheaper imported rice.[42]

Korea

Arable land in small alluvial flats of most rural river valleys in South Korea are dedicated to paddy-field farming. Farmers assess paddy fields for any necessary repairs in February. Fields may be rebuilt, and bund breaches are repaired. This work is carried out until mid-March, when warmer spring weather allows the farmer to buy or grow rice seedlings. They are transplanted (usually by rice transplanter) from the indoors into freshly flooded paddy fields in May. Farmers tend and weed their paddy fields through the summer until around the time of Chuseok, a traditional holiday held on 15 August of the Lunar Calendar (circa mid-September by Solar Calendar). The harvest begins in October. Coordinating the harvest can be challenging because many Korean farmers have small paddy fields in a number of locations around their villages, and modern harvesting machines are sometimes shared between extended family members. Farmers usually dry the harvested grains in the sun before bringing them to market.

The Hanja character for 'field', jeon (Korean: 전; Hanja: 田), is found in some place names, especially small farming townships and villages. However, the specific Korean term for 'paddy' is a purely Korean word, "non" (Korean: 논).

Madagascar

In Madagascar, the average annual consumption of rice is 130 kg per person, one of the largest in the world.

According to a 1999 study of UPDRS / FAO:

The majority of rice is related to irrigation (1,054,381 ha). The choice of methods conditioning performance is determined by the variety and quality control of water ..

The "Tavy", is traditionally the culture of flooded upland rice on burning of cleared natural rain forest (135,966 ha). Criticized as being the cause of deforestation, "Tavy" is still widely practiced by farmers in Madagascar, who find a good compromise between climate risks, availability of labour and food security.

"Tanety" means hill. By extension, the "tanety" is also growing upland rice, carried out on the grassy slopes have been deforested for the operation of charcoal. (139,337 ha)

Among the many varieties, rice of Madagascar include: "Vary lava" is a translucent long and large grain rice. It is a luxury rice. "Vary Makalioka, is translucent long and thin grain rice. "Vary Rojofotsy" is a half-long grain rice "Vary mena" or red rice, is exclusive to Madagascar.

Malaysia

Paddy fields can be found in most states on the Malaysian Peninsula, with most of the fields being located in the northern states such as Kedah, Perlis, Perak, and Penang. Paddy fields can also be found on Malaysia's east coast region, in Kelantan and Terengganu. The cetral state of Selangor also has its fair share of paddy fields, especially in the districts of Kuala Selangor and Sabak Bernam.

Before Malaysia became heavily reliant on its industrial output, people were mainly involved in agriculture, especially in the production of rice. It was for that reason, that people usually built their houses next to paddy fields. The very spicy chili pepper that is often eaten in Malaysia, the bird's eye chili, is locally called cili padi, literally "paddy chili". Some research pertaining to Rainfed lowland rice in Sarawak has been reported[1]

Myanmar

Rice is grown primarily in three areas – the Irrawaddy Delta, the area along and the delta of the Kaladan River, and the Central plains around Mandalay, though there has been an increase in rice farming in Shan State and Kachin State in recent years.[43] Up until the later 1960s, Myanmar was the main exporter of rice. Termed the rice basket of South East Asia, much of the rice grown in Myanmar does not rely on fertilizers and pesticides, thus, although "organic" in a sense, it has been unable to cope with population growth and other rice economies which utilized fertilizers.

Rice is now grown in all the three seasons of Myanmar, though primarily in the Monsoon season – from June to October. Rice grown in the delta areas rely heavily on the river water and sedimented minerals from the northern mountains, whilst the rice grown in the central regions require irrigation from the Irrawaddy River.

The fields are tilled when the first rains arrive – traditionally measured at 40 days after Thingyan, the Burmese New Year – around the beginning of June. In modern times, tractors are used, but traditionally, buffalos were employed. The rice plants are planted in nurseries and then transplanted by hand into the prepared fields. The rice is then harvested in late November – "when the rice bends with age". Most of the rice planting and harvesting are done by hand. The rice is then threshed and stored, ready for the mills.

Nepal

In Nepal, rice (Nepali: धान, Dhaan) is grown in the Terai and hilly regions. It is mainly grown during the summer monsoon in Nepal.[44]

Philippines

Paddy fields are a common sight in the Philippines. Several vast paddy fields exist in the provinces of Ifugao, Nueva Ecija, Isabela, Cagayan, Bulacan, Quezon, and other provinces. Nueva Ecija is considered the main rice growing province of the Philippines and the leading producer of onions in the Municipality of Bongabon in Southeast Asia. It is currently the 9th richest province in the country.

The Banaue Rice Terraces is an example of paddy fields in the country, it is located in Northern Luzon, Philippines and were built by the Ifugaos 2,000 years ago.[45] Streams and springs found in the mountains were tapped and channeled into Irrigation canals that run downhill through the rice terraces. Other notable Philippine paddy fields are the Batad Rice Terraces, the Bangaan Rice Terraces, the Mayoyao Rice Terraces and the Hapao Rice Terraces.[46]

Located at Barangay Batad in Banaue, the Batad Rice Terraces are shaped like an amphitheatre, and can be reached by a 12-kilometer ride from Banaue Hotel and a 2-hour hike uphill through mountain trails. The Bangaan Rice Terraces portray the typical Ifugao community, where the livelihood activities are within the village and its surroundings. The Bangaan Rice Terraces is accessible in a one-hour ride from Poblacion, Banaue, then a 20-minute trek down to the village. It can be viewed best from the road to Mayoyao. The Mayoyao Rice Terraces is located at Mayoyao, 44 kilometers away from Poblacion, Banaue. The town of Mayoyao lies in the midst of these rice terraces. All dikes are tiered with flat stones. The Hapao Rice Terraces can be reached within 55 kilometers from the capital town of Lagawe. Other Ifugao stone-walled rice terraces are located in the municipality of Hungduan.[46]

Sri Lanka

Agriculture in Sri Lanka mainly depends on rice production.[47] Sri Lanka sometimes exports rice to its neighboring countries. Around 1.5 million hectares of land is cultivated in Sri Lanka for paddy in 2008/2009 maha: 64% of which is cultivated during the dry season and 35% cultivated during the wet season. Around 879,000 farmer families are engaged in paddy cultivation in Sri Lanka. They make up 20% of the country's population and 32% of the employment.

Thailand

Rice production in Thailand represents a significant portion of the Thai economy. It uses over half of the farmable land area and labor force in Thailand.[48]

Thailand has a strong tradition of rice production. It has the fifth-largest amount of land under rice cultivation in the world and is the world's largest exporter of rice.[49] Thailand has plans to further increase its land available for rice production, with a goal of adding 500,000 hectares to its already 9.2 million hectares of rice-growing areas.[50] The Thai Ministry of Agriculture expected rice production to yield around 30 million tons of rice for 2008.[51] The most produced strain of rice in Thailand is jasmine rice, which has a significantly lower yield rate than other types of rice, but also normally fetches more than double the price of other strains in a global market.[50]

Vietnam

Rice fields in Vietnam (ruộng or cánh đồng in Vietnamese) are the predominant land use in the valley of the Red River and the Mekong Delta. In the Red River Delta of northern Vietnam, control of seasonal riverine floodings is achieved by an extensive network of dykes which over the centuries total some 3000 km. In the Mekong Delta of southern Vietnam, there is an interlacing drainage and irrigation canal system that has become the symbol of this area. It jointly serves as transportation routes, allowing farmers to bring their produce to market. In Northwestern Vietnam, Thai people built their "valley culture" based on the cultivation of glutinous rice planted in upland fields, requiring terracing of the slopes.

The primary festival related to the agrarian cycle is "lễ hạ điền" (literally "descent into the fields") held as the start of the planting season in hope of a bountiful harvest. Traditionally, the event was officiated with much pomp. The monarch carried out the ritual plowing the first furrow while local dignitaries and farmers followed suit. Thổ địa (deities of the earth), thành hoàng làng (the village patron spirit), Thần Nông (god of agriculture), and thần lúa (god of rice plants) were all venerated with prayers and offerings.

In colloquial Vietnamese, wealth is frequently associated with the vastness of the individual's land holdings. Paddy fields so large as for "storks to fly with their wings out-stretched" ("đồng lúa thẳng cánh cò bay") can be heard as a common metaphor. Wind-blown undulating rice plants across a paddy field in literary Vietnamese is termed figuratively "waves of rice plants" ("sóng lúa").

See also

References

- Sang, Anisia Jati; Tay, Kai Meng; Lim, Chee Peng; Saeid, Nahavandi (2018). "Application of a Genetic-Fuzzy FMEA to Rainfed Lowland Rice Production in Sarawak: Environmental, Health, and Safety Perspectives". IEEE Access. 6: 74628–74647. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2883115.

- "Riz de Camargue, Silo de Tourtoulen, Riz blanc de Camargue, Riz et céréales de Camargue". Riz-camargue.com. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- "Methane Sources – Rice Paddies". Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- "Scientists blame global warming on rice". Sptimes.com. 2 May 2007. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- "Shifts in rice farming practices in China reduce greenhouse gas methane". Archived from the original on 11 January 2003. Retrieved 19 December 2002.

- Mishra S. N., Mitra S., Rangan L, Dutta S., and Pooja. (2012). Exploration of 'hot-spots' of methane and nitrous oxide emission from the agriculture fields of Assam, India. Agriculture and Food Security. 1/16. doi:10.1186/2048-7010-1-16. Online link http://www.agricultureandfoodsecurity.com/content/1/1/16

- "paddy". Merriam Webster. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- Blust, Robert; Trussel, Stephen. "Cognate Sets: *p". Austronesian Comparative Dictionary. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- Molina, J.; Sikora, M.; Garud, N.; Flowers, J. M.; Rubinstein, S.; Reynolds, A.; Huang, P.; Jackson, S.; Schaal, B. A.; Bustamante, C. D.; Boyko, A. R.; Purugganan, M. D. (2011). "Molecular evidence for a single evolutionary origin of domesticated rice". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (20): 8351–6. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.8351M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1104686108. PMC 3101000. PMID 21536870.

- Gross, B. L.; Zhao, Z. (2014). "Archaeological and genetic insights into the origins of domesticated rice". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 111 (17): 6190–7. Bibcode:2014PNAS..111.6190G. doi:10.1073/pnas.1308942110. PMC 4035933. PMID 24753573.

- Zhang, Jianping; Lu, Houyuan; Gu, Wanfa; Wu, Naiqin; Zhou, Kunshu; Hu, Yayi; Xin, Yingjun; Wang, Can; Kashkush, Khalil (17 December 2012). "Early Mixed Farming of Millet and Rice 7800 Years Ago in the Middle Yellow River Region, China". PLOS ONE. 7 (12): e52146. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...752146Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052146. PMC 3524165. PMID 23284907.

- He, Keyang; Lu, Houyuan; Zhang, Jianping; Wang, Can; Huan, Xiujia (7 June 2017). "Prehistoric evolution of the dualistic structure mixed rice and millet farming in China". The Holocene. 27 (12): 1885–1898. Bibcode:2017Holoc..27.1885H. doi:10.1177/0959683617708455. S2CID 133660098.

- Bellwood, Peter (9 December 2011). "The Checkered Prehistory of Rice Movement Southwards as a Domesticated Cereal—from the Yangzi to the Equator" (PDF). Rice. 4 (3–4): 93–103. doi:10.1007/s12284-011-9068-9. S2CID 44675525.

- Hsieh, Jaw-shu; Hsing, Yue-ie Caroline; Hsu, Tze-fu; Li, Paul Jen-kuei; Li, Kuang-ti; Tsang, Cheng-hwa (24 December 2011). "Studies on Ancient Rice—Where Botanists, Agronomists, Archeologists, Linguists, and Ethnologists Meet". Rice. 4 (3–4): 178–183. doi:10.1007/s12284-011-9075-x.

- Li, Hui; Huang, Ying; Mustavich, Laura F.; Zhang, Fan; Tan, Jing-Ze; Wang, ling-E; Qian, Ji; Gao, Meng-He; Jin, Li (2007). "Y chromosomes of prehistoric people along the Yangtze River" (PDF). Human Genetics. 122 (3–4): 383–388. doi:10.1007/s00439-007-0407-2. PMID 17657509. S2CID 2533393. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 December 2013.

- Cao, Zhihong; Fu, Jianrong; Zou, Ping; Huang, Jing Fa; Lu, Hong; Weng, Jieping; Ding, Jinlong (August 2010). "Origin and chronosequence of paddy soils in China". Proceedings of the 19th World Congress of Soil Science: 39–42. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- Bellwood, Peter (1997). "Prehistory of the Indo-Malaysian Archipelago". Prehistory of the Indo-Malaysian Archipelago: Revised Edition. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. pp. 205–211. ISBN 0824818830. JSTOR j.ctt24hf81.

- Fujiwara, H. (ed.). Search for the Origin of Rice Cultivation: The Ancient Rice Cultivation in Paddy Fields at the Cao Xie Shan Site in China. Miyazaki: Society for Scientific Studies on Cultural Property, 1996. (In Japanese and Chinese)

- Fujiwara 1996

- Tsude, Hiroshi. Yayoi Farmers Reconsidered: New Perspectives on Agricultural Development in East Asia. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association 21(5):53–59, 2001.

- "Expansion of Chinese Paddy Rice to the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 6 August 2007.

- Zhang, Chi; Hung, Hsiao-Chun (2008). "The Neolithic of Southern China – Origin, Development, and Dispersal" (PDF). Asian Perspectives. 47 (2).

- Zhang, Chi (2013). "The Qujialing–Shijiahe culture in the middle Yangzi River valley". In Underhill, Anne P. (ed.). A Companion to Chinese Archaeology. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 510–534. ISBN 9781118325780.

- Liu, Li; Chen, Xingcan (2012). The Archaeology of China: From the Late Paleolithic to the Early Bronze Age. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521643108.

- Major, John S.; Cook, Constance A. (2016). Ancient China: A History. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781317503668.

- Beaujard, Philippe (August 2011). "The first migrants to Madagascar and their introduction of plants: linguistic and ethnological evidence" (PDF). Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa. 46 (2): 169–189. doi:10.1080/0067270X.2011.580142. S2CID 55763047.

- Crawford, Gary W. and Gyoung-Ah Lee. Agricultural Origins in the Korean Peninsula. Antiquity 77(295):87–95, 2003.

- Crawford and Lee 2003

- Bale, Martin T. Archaeology of Early Agriculture in Korea: An Update on Recent Developments. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association 21(5):77–84, 2001.

- Bale 2001

- Kwak, Jong-chul. Urinara-eui Seonsa – Godae Non Bat Yugu [Dry- and Wet-field Agricultural Features of the Korean Prehistoric].In Hanguk Nonggyeong Munhwa-eui Hyeongseong [The Formation of Agrarian Societies in Korea]: 21–73. Papers of the 25th National Meetings of the Korean Archaeological Society, Busan, 2001

- Barnes, Gina L. Paddy Soils Now and Then. World Archaeology 22(1):1–17, 1990.

- fao.org (FAOSTAT). "Countries by commodity (Rice, paddy)". Retrieved 11 February 2014.

- Crawford and Shen 1998

- Harrington, Spencer P.M. (11 June 1997). "Earliest Rice". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America.

Rice cultivation began in China ca. 11,500 years ago, some 3,500 years earlier than previously believed

- Normile, Dennis (1997). "Yangtze seen as earliest rice site". Science. 275 (5298): 309–310. doi:10.1126/science.275.5298.309. S2CID 140691699.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd. Page 271.

- Angus, Maddison (21 September 2006). The World Economy, Angus Maddison, p.20, ISBN 92-64-02261-9. ISBN 9789264022614. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- "Top 10 Rice Producing States of India, Indian States with Highest Rice Production". Mapsofindia.com. 17 January 2012. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- "Lansing and Miller" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- "Channel 4 notes for schools". Channel4.com. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- "Economist.com". The Economist. 17 December 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2013.

- "Increasing rice production in Myanmar". Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 4 May 2015.

- "New Agriculturist: Country profile - Nepal". www.new-ag.info.

- UNESCO World Heritage Centre. "Rice Terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras – UNESCO World Heritage Centre". Whc.unesco.org. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

- "Error". Retrieved 1 April 2011.

- "Rice Knowledge for Sri Lanka - IRRI Rice Knowledge Bank". www.knowledgebank.irri.org.

- Country Profile: Thailand. lcweb2.loc.gov 7 (July 2007).

- Thailand backs away from rice cartel plan." The International Herald Tribune 7 May 2008: 12. 2 February 2009, lexisnexis.com

- "Rice strain is cause of comparatively low productivity." The Nation (Thailand) 16 April 2008. 2 February 2009, lexisnexis.com

- Nirmal, Ghost. "Thailand to set aside more land for farming; It plans to increase rice production and stop conversion of agricultural land." The Straits Times (Singapore) 24 April 2008.

Bibliography

- Bale, Martin T. Archaeology of Early Agriculture in Korea: An Update on Recent Developments. Bulletin of the Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association 21(5):77–84, 2001.

- Barnes, Gina L. Paddy Soils Now and Then. World Archaeology 22(1):1–17, 1990.

- Crawford, Gary W. and Gyoung-Ah Lee. Agricultural Origins in the Korean Peninsula. Antiquity 77(295):87–95, 2003.

- Kwak, Jong-chul. Urinara-eui Seonsa – Godae Non Bat Yugu [Dry- and Wet-field Agricultural Features of the Korean Prehistoric].In Hanguk Nonggyeong Munhwa-eui Hyeongseong [The Formation of Agrarian Societies in Korea]: 21–73. Papers of the 25th National Meetings of the Korean Archaeological Society, Busan, 2001.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paddy fields. |

| Look up paddy field in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |