Lê dynasty

The Lê dynasty, also known as Later Lê dynasty (Vietnamese: Hậu Lê triều Hán tự: 後黎朝[lower-alpha 2] or Vietnamese: nhà Hậu Lê Hán tự: 家後黎[lower-alpha 3]), was the longest-ruling Vietnamese dynasty, ruling Đại Việt from 1428 to 1789. The Lê dynasty is divided into two historical periods – the Early period or Lê sơ triều (Hán tự: 黎初朝; 1428–1527) before usurpation by the Mạc dynasty (1527–1683), in which emperors ruled in their own right, and the restored period or Revival Lê (Lê Trung hưng triều) (Hán tự: 黎中興朝; 1533–1789), in which figurehead emperors reigned under the auspices of the powerful Trịnh family. The Restored Lê period is marked by two lengthy civil wars: the Lê–Mạc War (1533–1592) in which two dynasties battled for legitimacy in northern Vietnam and the Trịnh–Nguyễn War (1627-1672) between the Trịnh family in Tonkin and the Nguyễn lords of the South.

Đại Việt Đại Việt Quốc (大越國) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1428–1789 | |||||||||

.svg.png.webp) Map of Đại Việt in 1770 under the reign of emperor Lê Hiển Tông which also showed the division of Vietnamese territory among Nguyễn lords in Cochinchina, Trịnh lords in Tonkin. | |||||||||

| Status | Internal imperial system within Chinese tributary[1][2][3] (Ming 1428–1644) (Southern Ming 1644–1667) (Qing 1667–1789) | ||||||||

| Capital | Đông Kinh (1428–1527 and 1597–1789) Tây Kinh (temp) (1533–1597) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Written Classical Chinese[4]:207[lower-alpha 1]Middle VietnameseOther local languages | ||||||||

| Religion | Vietnamese folk religion, Confucianism (state ideology),[5] Buddhism, Taoism, Islam,[6] Roman Catholicism | ||||||||

| Government | Absolute monarchy | ||||||||

| Emperor (Hoàng đế) | |||||||||

• 1428–1433 (first) | Lê Thái Tổ | ||||||||

• 1522–1527 | Lê Cung Hoàng | ||||||||

• 1533–1548 | Lê Trang Tông | ||||||||

• 1786–1789 (last) | Lê Chiêu Thống | ||||||||

| Historical era | Early modern | ||||||||

| 1418–1427 | |||||||||

• Coronation of Lê Lợi | 29 April 1428 | ||||||||

• Mạc Đăng Dung usurped the throne | 15 June 1527 | ||||||||

• Recapture of Đông Kinh | December 1592 | ||||||||

| January 30 1789 | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1479 | 450,000 km2 (170,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| 1490 | 300,000 km2 (120,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| 1770 | 350,000 km2 (140,000 sq mi) | ||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1479 | 7,500,000 | ||||||||

• 1490 | 7,700,000[7] | ||||||||

• 1770 | 9,246,000 | ||||||||

| Currency | Văn (文) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Vietnam Laos Cambodia China | ||||||||

| Lê dynasty | |

| Vietnamese alphabet | Hậu Lê triều |

|---|---|

| Hán-Nôm | Hậu Lê triều |

| Chữ Hán | 後黎朝 |

| Chữ Nôm | 後黎朝 |

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Vietnam |

|

| Timeline |

|

|

The dynasty officially began in 1428 with the enthronement of Lê Lợi after he drove the Ming army from Vietnam. The dynasty reached its peak during the reign of Lê Thánh Tông and declined after his death in 1497. In 1527, the Mạc dynasty usurped the throne; when the Lê dynasty was restored in 1533, the Mạc fled to the far north and continued to claim the throne during the period known as Southern and Northern Dynasties. The restored Lê emperors held no real power, and by the time the Mạc dynasty was finally eradicated in 1677, actual power lay in the hands of the Trịnh lords in the North and Nguyễn lords in the South, both ruling in the name of the Lê emperor while fighting each other. The Lê dynasty officially ended in 1789, when the peasant uprising of the Tây Sơn brothers defeated both the Trịnh and the Nguyễn, ironically in order to restore power to the Lê dynasty.

The Lê dynasty expanded Vietnam's borders through the domination of the Kingdom of Champa and expedition into today Laos and Myanmar, nearly reaching Vietnam's modern borders by the time of the Tây Sơn uprising. It also saw massive changes to Vietnamese society: the previously Buddhist state became Confucian after the preceding 20 years of Ming rule. The Lê emperors instituted many changes modeled after the Chinese system, including the civil service and laws. Their long-lasting rule was attributed to the popularity of the early emperors. Lê Lợi's liberation of the country from 20 years of Ming rule and Lê Thánh Tông's bringing the country into a golden age was well-remembered by the people. Even though the restored Lê emperors' rule was marked by civil strife and constant peasant uprisings, few dared to openly challenge their power for fear of losing popular support. The Lê dynasty also was the period Vietnam saw the coming of Western Europeans and Christianity in early 16th-century.[8]

History

Lam Sơn uprising (1418–1427)

During the Fourth Chinese domination of Vietnam, Lê Lợi led an uprising against the rule of the Ming dynasty in 1418,[9][10][11][12][13] after two earlier rebellions of two Vietnamese princes Trần Ngỗi and Trần Quý Khoáng in 1409 and 1413, respectively, were crushed by the Ming military. Lê Lợi was a member of the Lê (黎) clan from Thanh Hoá, whose mixed Chinese-Vietnamese origins include the Han Chinese governor of Jiuzhen, Lê Ngọc 黎玉 (535–618), who had led a failed rebellion against the Tang Empire in 618 CE.[14] Lê Lợi was a son of wealthy Vietnamese aristocrat in Thanh Hoá. He early life was briefly mentioned in the Chinese source as a low-rank official serving the Ming governor Hoang Fu.[15] He joined a secret Taoist swearing commentary in Lũng Nhai, Thanh Hoá in winter 1916, with other 18 men, all swore will fought against the Ming Chinese, restore the Vietnamese independence and sovereignty.[16]

The Lam Sơn ("blue mountain") campaign began on the day after Tết (Lunar New Year) in February 1418.[17] In November 1424, the Lam Sơn captured the Nghệ An citadel in a surprise attack from their base in Laos, leading to the retreat of the ethnic-Vietnamese Ming commander Lương Nhữ Hốt (Liang Juihu) to the north. From their new base in high-density population Nghệ An, Lê Lợi's rebel forces captured the territory in modern-day central Vietnam, from Thanh Hoá to Đà Nẵng.[18] By August 1426, the Lam Sơn rebellion launched an offensive to the north with new forces against a fresh Ming army commanded by Wang Tong in charge of defending northern Vietnam.[19] The new Ming ruler, the Xuande Emperor, wished to end the war with Vietnam, but his advisors urged one more effort to subdue the rebellious province. Consequently, the Ming sent a large army of approximately 100,000 men to Vietnam.[20] After the pivotal Battle of Tốt Động – Chúc Động in October 1426, the Ming Dynasty withdrew by 1428.[21] By early 1427, Lê Lợi's forces had controlled most of northern Vietnam, advancing as far as the southern tip of modern-day Guangxi. Following negotiations with the Ming, Lê Lợi selected Trần Cảo as a puppet king of Annam who nominally ruled from 1426 to 1428.[22][21]

Lê Lợi (1428–1433)

In 1428, Lê Lợi established the Lê dynasty and took the reign name Lê Thái Tổ, receiving recognition and formal protection from the Ming dynasty in a tributary relationship.[1][2][3][23]

In 1429, he introduced the Thuận Thiên code, largely based on the Tang Code, with severe charges for gambling, bribery and corruption.[24][25] Lê Lợi granted a land reform in 1429 that took lands from people who collaborated with the Chinese and distributed them among landless peasants and soldiers. He distrusted many of his former generals, resulting in the 1430 execution of the two generals Trần Nguyên Hãn and Phạm Văn Xảo that is considered by Vietnamese historians as a political purge.[26]

Lê Lợi's reign would be short-lived, as he died in 1433.[27]

Lê Thái Tông (ruled 1433–1442)

Lê Thái Tông (黎太宗, ruled 1433–1442) [28] was the official heir to Lê Lợi. However, he was just eleven, so a close friend of Lê Lợi, Lê Sát, assumed the regency of the kingdom. Not long after he assumed the official title as Emperor of Vietnam in 1438, Lê Thái Tông accused Lê Sát of abuse of power and had him executed. In December 1435, Thái Tông ordered general Tư Mã Tây to subdue the Tày chief Cầm Quý who having a ten-thousand army of raiders in the northwest region.[29] In January 1436, the emperor ordered to make roads and canals from northwest region to the capital for showing the superior power of the Imperial court to the local tribes men.[30] From 1437 to 1441, tribe men from Ai-Lao crossed the Annamite Range, raided in Thanh Hóa and southern Hưng Hóa (now Sơn La province) with the help of the local raiders led by Nghiễm Sinh Tượng were suppressed by the Imperial army.[31] The Lê Dynasty started treating hostilely to the ethnic minorities in western region. On a stone monument that was carved in 1439 under Thái Tông's reign said "Bồn-Man (Muang Phuan) barbarians were against our assimilation, they need to be exterminated to their roots, and with the Sơn-Man (Mường and Chứt) barbaric raiders, we need to eliminated all of them,..."[32]

According to a Mạc–Trịnh version of Complete Annals of Đại Việt, the new Emperor had a weakness for women. He had many wives, and he discarded one favorite after another. The most prominent scandal was his affair with Nguyễn Thị Lộ, the wife of his father's chief advisor Nguyễn Trãi. The affair started early in 1442 and continued when the Emperor traveled to the home of Nguyễn Trãi, who was venerated as a great Confucian scholar.

Shortly after the Emperor left Trãi's home to continue his tour of the western province, he fell ill and died. At the time the powerful nobles in the court argued that the Emperor had been poisoned to death. Nguyễn Trãi was executed as were his three entire relations, the normal punishment for treason at that time.

Lê Nhân Tông (ruled 1442–1459)

With the Emperor's sudden death at a young age, his infant heir Bang Co was made emperor- although he was the second son of his father, his older brother Nghi Dân had been officially passed over due to his mother's low social status. Bang Co assumed the throne as Lê Nhân Tông (黎仁宗) [28] but the real rulers were Trịnh Khả and the child's mother, the young Empress Nguyễn Thị Anh. The next 17 years were good years for Vietnam – there were no great troubles either internally or externally. Two things of note occurred: first, the Vietnamese sent an army south to attack the Champa kingdom in 1446; second, the Dowager Empress ordered the execution of Trịnh Khả, for reasons lost to history, in 1451.

In 1453 at the age of twelve, Lê Nhân Tông was formally given the title of Emperor. This was unusual as according to custom, youths could not ascend the throne till the age of 16. It may have been done to remove Nguyễn Thi Anh from power, but if that was the reason, it failed and the Dowager Empress still controlled the government up until a coup in 1459.

In 1459, Lê Nhân Tông's older brother, Nghi Dân, plotted with a group of followers to kill the Emperor. On October 28, the plotters with some 100 "shiftless men" infiltrated the palace and murdered the Emperor (he was just 18). The next day, facing certain execution the Dowager Empress committed suicide. The rule of Nghi Dân was brief, and he was never officially recognized as a sovereign by later Vietnamese historians. Revolts against his rule started almost immediately and the second revolt, occurring on June 24, 1460, succeeded. The rebels, led by Lê Lợi's surviving former advsiors Nguyễn Xí and Dinh Liêt captured and killed Nghi Dân along with his followers. The rebels then selected the youngest son of Lê Thái Tông to be the new Emperor, who they proclaimed to be Lê Thánh Tông.

Lê Thánh Tông (ruled 1460–1497)

.png.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Quang Thuận Hoàng Đế (光順皇帝),[28] whose reign was named Hồng Đức Thịnh Thế (洪德之盛治, "Prosperous reign of Hồng Đức"), instituted a wide range of government reforms, legal reforms, and land reforms. He restarted the examination system for selecting men for important government positions. He reduced the power of the noble families and reduced the degree of corruption in the government. He built temples to Confucius throughout the provinces of Đại Việt. In nearly all respects, his reforms mirrored those of the Ming dynasty. Thánh Tông was strongly influenced by his Confucian teachers and he resolved to make Việt Nam more like the Ming Dynasty with its Neo-Confucianist philosophy and the key idea that the government should be run by men of noble character as opposed to men from noble families. This meant that he needed to take power away from the ruling families (mostly from Thanh Hóa province) and give power to the scholars who did well on the official examinations. The first step on this path was to revive the examination process, which had continued sporadically in the 1450s. The first examination was held in 1463 and, as expected, the top scholars were men from elsewhere- usually from the river delta surrounding the capital, not from Thanh Hóa.

Thánh Tông encouraged the spread of Confucian values throughout Vietnam by having "temples of literature" built in all the provinces. There, Confucius was venerated and classic works on Confucianism could be found. He also halted the building of any new Buddhist or Taoist temples and ordered that monks were not to be allowed to purchase any new land.

Following the Chinese model, Lê Thánh Tông divided the government into six ministries; they were Finance, Rites, Justice, Personnel, Army, and Public Works. Nine grades of rank were set up for both the civil administration and the military. A Board of Censors was set up with royal authority to monitor governmental officials and reported exclusively to the emperor. However, governmental authority did not extend all the way to the village level. The villages were ruled by their own councils in Vietnam.[33]

With the death of Nguyễn Xí in 1465, the noble families from Thanh Hóa province lost their leader. Soon they were mostly relegated to secondary positions in the new Confucian government of Thánh Tông. However, they still retained control over Vietnam's armies as the old general, Đinh Liệt, was still in command of the army. In the same year, Vietnam was attacked by Ryukyuan pirates from the northeast. This was dealt with by sending additional forces to the north to fight the pirates. Thánh Tông also sent a military force to the west to subdue the Ai-lao mountain tribes that was raiding the northwest border.

In 1469, all of Vietnam was mapped and a full census was taken, listing all the villages in the Empire. Around this time the country was divided into 13 dao (provinces). Each was administrated by a Governor, Judge, and the local army commander. The emperor Thánh Tông also ordered that a new census should be taken every six years. Other public works that were undertaken included building and repair of granaries, using the army to rebuild and repair irrigation systems after floods, and sending out doctors to areas afflicted by outbreaks of disease. Even though the emperor, at 25, was relatively young, he had already restored Vietnam's stability, which was a marked contrast from the turbulent times marking the reigns of the two emperors before him.

Several Malay envoys from the Malacca sultanate were attacked and captured in 1469 by Vietnamese navy as they were returning to Malacca from China. The Vietnamese enslaved and castrated the young from among the captured.[34][35][36][37][38] A 1472 entry in the Ming Shilu reported that some Chinese from Nanhai escaped back to China after their ship had been blown off course into Vietnam, where they had been forced to serve as soldiers in Vietnam's military. The escapees also reported that up to 100 Chinese men remained captives in Vietnam after they were caught and castrated by the Vietnamese after their ships were blown off course into Vietnam. The Chinese Ministry of Revenue responded by ordering Chinese civilians and soldiers to stop going abroad to foreign countries.[39][40][41] China's relations with Vietnam during this period were marked by the punishment of prisoners by castration.[42][43]

Under the order of Lê Thánh Tông, the official historical text of the Lê Dynasty, Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư (大越史記全書), was compiled and finished in 1479. The 15-volume book covered the entirety of Vietnamese history at that point, from the Hồng Bàng Dynasty to the enthronement of Lê Thái Tổ.

Hồng Đức's campaigns against Champa and Lan Xang (1471–1480)

In 1471, Lê Thánh Tông conquered Champa and captured the Cham capital Vijaya, ending independent Cham rule in the south. The Kingdom of Champa was reduced to a small enclave near Panduranga (modern day Phan Rang–Tháp Chàm) and Kauthara (now Nha Trang) with many Chams fleeing to Cambodia.[44][45] Lê Thánh Tông created a new province out of former Cham land and allowed ethnic Vietnamese settlers to settle it. The conquest of the Cham kingdoms started a rapid period of expansion by the Vietnamese southwards into this newly conquered land. The government used a system of land settlement called đồn điền (屯田)..

From 1478 to 1480, Lê Thánh Tông led an expedition against the kingdoms of Lan Xang and Lanna in today Laos and Northern Thailand.[46] Laotians were overwhelmed, their capital Luang Prabang was captured. Laotians retreated to the jungles, waged two-years guerrilla warfare against the Vietnamese.[46] King of Lan Xang Chakkaphat Phaen Phaeo seek refugee in Lanna.[46] Some of the Vietnamese army had reached the kingdom of Ava.[47] The expedition ended in inclusive, many Vietnamese soldiers died because of the hostile climate and rampant diseases;[48] The Vietnamese forces were unable to suppressed the Laotian guerrillas, and then the Laotians were able to recaptured their capital.[46] As the Vietnamese withdrew their army through the kingdom of Muang Phuan in December 1479, they annexed and incorporated it into Ninh Protectorate (Trấn Ninh) in 1480.[49]

Decline of the Early period

With the death of Lê Thánh Tông, the Lê dynasty fell into a swift decline (1497–1527).

Prince Lê Tăng, the eldest of Lê Thánh Tông's 14 sons, succeeded his father as Lê Hiến Tông (黎憲宗). He was 38 years old at the time of his father's death. He was an affable, meek and mild-mannered person. Due to his short period of rule and that he didn't pass many significant reforms, his reign is considered to be an extension of Lê Thánh Tông's rule. The new emperor was known to historical annals as Lê Hiến Tông. In early 1499, several high-ranking officials including Lê Vĩnh and Lê Năng Nhượng persuaded Hiến Tông to choose an heir in order to maintain the dynasty's and the nation's security and sustainability. Hiến Tông agreed; and although the emperor had two elder sons: Lê Tuân and Lê Tuấn, Lê Thuần was designed as crown prince due to his deep interest in intellectuality and Neo-Confucianism, which caused Hiến Tông to perceive him as being far superior to his two older brothers.[50]

Lê Hiến Tông chose his third son, Lê Túc Tông (黎肅宗) to be his successor. The 17 year-old Lê Túc Tông was portrayed by court chroniclers as a wise emperor who maintained harmony in the court. In 1504, Lê Hiến Tông died at 44 years old. The 17th years old Lê Thuần inherited the throne. The Confucian annalists portrayed him as a relatively good emperor who released many prisoners, stopping several construction works that posed heavy burden on his subjects, as well as reducing tributes from vassals and holding high-ranking officials in high regard. He was also said to have maintained harmony in the court and the whole country. In the other hand, the annals also recorded a revolt broke in Cao Bằng, led by Đoàn Thế Nùng against the government. Lê Thuần sent troops to Cao Bằng, defeating and killing Đoàn Thế Nùng along with 500 rebels.[51] In 1504, Lê Hiến Tông died at 44 years old. The 17th years old Lê Thuần inherited the throne. The Confucian annalists portrayed him as a relatively good emperor who released many prisoners, stopping several construction works that posed heavy burden on his subjects, as well as reducing tributes from vassals and holding high-ranking officials in high regard. He was also said to have maintained harmony in the court and the whole country. In the other hand, the annals also recorded a revolt broke in Cao Bằng, led by Đoàn Thế Nùng against the government. Lê Thuần sent troops to Cao Bằng, defeating and killing Đoàn Thế Nùng along with 500 rebels.[51] However, he fell gravely ill and died just six months after assuming the throne.

Lê Uy Mục (黎威穆) was the second son of Emperor Lê Hiến Tông. In 1505, as older brother of Emperor Lê Túc Tông, he succeeded the throne, later known under posthumous name Uy Mục hoàng đế (威穆皇帝). Lê Uy Mục was portrayed by Neo-Confucianist chroniclers as being deeply contrasted to his predecessors Lê Thánh Tông, Lê Hiến Tông and Lê Túc Tông, who closely followed Neo-Confucianist principles in governing the nation.[51] The first thing the new emperor did was to take revenge against those who had barred him from the throne by having them killed. Among his victims were the former emperor's mother – which was considered[52] a shocking display of evil behavior. Lê Uy Mục was described by a Ming ambassador – as a cruel, sadistic, and depraved person, who wasted the court's money and finances to indulge his whims. Well aware that he was detested by his subjects, Lê Uy Mục protected himself by hiring a group of elite bodyguards to surround him at all times. Among them was Mạc Đăng Dung, who became very close to the emperor and eventually rose to the rank of general. Despite his precautions, in 1509 a cousin, whom Lê Uy Mục had put in prison, escaped and plotted with court insiders to assassinate the emperor. The assassination succeeded and the killer proclaimed himself emperor under the name Lê Tương Dực.

Lê Tương Dực (黎襄翼), posthumous name Tương Dực Hoàng đế (襄翼皇帝), proved to be just as bad a ruler as Lê Uy Mục. He reigned from 1510 to 1516, all the while spending down the royal treasury, and doing nothing to improve the country. He was heedless to the reaction that his taxes caused throughout the country. Later in his reign, he spent extravagantly in building many colossal palaces in the imperial capital, Thăng Long. The most notable of those places was one known to the Vietnamese as Cửu Trùng Đài, designed by the emperor's favoured architect Vũ Như Tô. He also spent much time enjoying sexual activities with his concubines, many of whom were former concubines of Lê Hiến Tông and Lê Uy Mục. According to court chroniclers, he ordered the build of special boats for his nude concubines to row on large artificial lakes.[53] As the result of the emperor's luxurious lifestyle and ignorance of state affairs, the people suffered considerable hardships. Many soldiers committed to build imperial palaces died due to diseases.[53] As the government became increasingly unpopular, many rebellions broke out. The largest of them was that of Trần Cảo, a northerner who claimed to be an heir of the House of Trần.[54] His rule ended in 1516 when a group officials and generals led by Trịnh Duy Sản stormed the palace and killed him.[55][56]

Crisis and revolts

At 14 years old, nephew of Lê Tương Dực, prince Lê Y, was enthroned as the new emperor Lê Chiêu Tông (ruled 1516–1522).[28] Factions within the court vied with one another for control of the government. One powerful and growing faction was led by Mạc Đăng Dung, a military leader who rose through the ranks.[57] His growing power was resented by the leaders of two noble families in Vietnam: the Nguyễn, under Nguyễn Hoàng Dụ and the Trịnh, under Trịnh Duy Đại and Trịnh Duy Sản. After several years of increasing tension, the Nguyễn and the Trịnh left the capital Hanoi (then called Đông Đô) and fled south, with the Emperor "under their protection".

In 1524, Mạc Đăng Dung forces captured and executed the leaders of the revolt (Nguyễn Hoàng Du, Trịnh Duy Đại, and Trịnh Duy Sản). The revolt by the Trịnh clan and the Nguyễn clan was defeated for the moment. This was the start of a civil war with Mạc Đăng Dung and his supporters on one side and the Trịnh and the Nguyễn on the other side. Thanh Hóa Province, the ancestral home to the Trịnh and the Nguyễn, was the battle ground between the two sides. After several years of warfare, Emperor Lê Chiêu Tông was assassinated in 1522 by Mạc Đăng Dung's supporters. Not long after, the leaders of the Nguyễn and the Trịnh were executed. Mạc Đăng Dung was now the most powerful man in Vietnam.

Usurpation of Mạc Đăng Dung

The degenerated Lê dynasty, which endured under six rulers between 1497 and 1527, in the end was no longer able to maintain control over the northern part of the country, much less the new territories to the south. The weakening of the monarchy created a vacuum that the various noble families of the aristocracy were eager to fill. Soon after Lê Chiêu Tông fled south with the Trịnh and the Nguyễn in 1522, Mạc Đăng Dung proclaimed the Emperor's younger brother, Lê Xuân, as the new Emperor under the name Lê Cung Hoàng. In reality, the new Emperor had no power. Three years after Mạc's forces killed his older brother Lê Chiêu Tông, was pressured from Mạc Đăng Dung, in Bắc Sứ garden, Lê Cung Hoàng hanged himself on 18 June 1527. Mạc Đăng Dung, being a scholar-official who had effectively controlled the Lê for a decade, murdered all the Lê royal family member then proclaimed himself the new Emperor of Vietnam on 15 June 1527, ending (so he thought) the Lê dynasty (see Mạc dynasty for more details).

Mạc Đăng Dung's seizure of the throne prompted other families of the aristocracy, notably the Nguyễn and Trịnh, to rush to the support of the Lê royalists. With the usurpation of the throne, the civil war broke out anew. Again the Nguyễn and the Trịnh gathered an army and fought against Mạc Đăng Dung, this time under the leadership of Nguyễn Kim and Trịnh Kiểm. The Trịnh and the Nguyễn were nominally fighting on behalf of the Lê emperor but in reality, for their own power.

Southern and Northern Dynasties (1533–1597)

The Lê royalists under Lê Ninh, a descendant of the Royal family, escaped to Muang Phuan (today Laos). Marquis of An Thanh Nguyễn Kim summoned the people who were still loyal to the Lê emperor and formed a new army to begin a revolt against Mạc Đăng Dung. Subsequently, Nguyễn Kim returned to Đại Việt and led the Lê royalists in a sixty-year-long civil war. In 1536 and 1537, Nguyên Hòa sent two envoys to Beijing to ask Jiajing Emperor of Ming Dynasty to send army fight against the Mạc to restore the Lê Dynasty.[58] Many Ming officials like Mao Bá Ôn showed strong supports for the Lê royalists and urged Jiajing Emperor for prepare a military campaign.[59] The Ming Emperor agreed.[60]

In 1527, the Vũ Văn (Wuwen) clan in Hà Giang and northern Hưng Hóa (now southern Yunnan) rebelled against Mạc Đăng Dung and set up their own government. Vũ Văn Uyên and his family rules were called Bầu Lords. In 1534, after Nguyễn Kim forces recaptured Thanh Hóa, Vũ Văn Uyên declared allied with Lê royalists and Ming army to fought against the Mạc Dynasty.[61] But Mạc Đăng Dung himself in 1540 went and surrendered the Ming army, wished for peace. Mạc Đăng Dung ceded the northeast Vietnamese coastal to the Ming Dynasty for exchanging that the Ming dynasty would never invade Vietnam again.[62] The Chinese now recognized both Mạc and Lê legitimacy over Đại Việt and withdrew their army.[63] Bầu Lords showed strong support for the Lê dynasty and refused to accept Trịnh family at the early stage of Trịnh–Nguyễn War. Later, they cooperated with the Trịnh. Bầu Lords lasted for nearly 200 years from 1527 to 1699.

In 1542, Lê army from Muang Phuan recaptured Nghệ An. Mạc general Dương Chấp Nhất surrendered.[64] After capturing the region of Thanh Hóa and Nghệ An, the Revival Lê dynasty eventually recaptured three-quarters of their former kingdom. Inasmuch as the Mac dynasty ruled the northern portion of Đại Việt while the Lê dynasty ruled the remainder of the country, this time became known as the period of Northern and Southern dynasties.

In 1545, Nguyễn Kim was poisoned by Dương Chấp Nhất), a surrendered general of the Mạc dynasty. The power of royal court was then passed to Nguyễn Kim's son-in-law Trịnh Kiểm who became the founder of the Trịnh lords. Since then the emperor has only become a figurehead, Trịnh Kiểm and his successors were the de facto rulers of the country and continue the war with the Mạc. The war has three actual fighting periods: 1533–1537, 1551–1564 and 1584–1592. During the early confront period, the Lê dynasty introduced personnel firearm like matchlocks into their army and surprised the Mạc army.[65][66]

Trịnh Tùng succeed his father in 1570, established the Trịnh lords and launched a large-scale offensive against the Mạc army in January 1592.[67] Unable to resist the forces of the Lê royalists, in December 1592 the Mạc dynasty retreated to the north and established a new capital at Cao Bằng Province allying with the Ming dynasty of China as a tributary nation against the Lê dynasty.

Restored Lê (1597–1789)

In 1597, the Ming dynasty recognized the legitimacy of the Lê monarch.[68] However, the Ming recorded that the Lê rulers were very dissatisfied to the Ming Empire because the Chinese had supported for the Northern Mạc. In 1589, Toyotomi Hideyoshi sent an envoys to Lê court in Thanh Hoá, called Vietnamese to join Japan's alliance against Ming China and Joseon Korea.[69] In Toyotomi Hideyoshi's view, Japan's attack on the Ming Dynasty from the northeast, Vietnam from the south, and Southeast Asian countries from the southeast to the north will inevitably put the Ming Dynasty into a state of exhaustion.[69] Although some people supported for the plan, the Lê emperor Quang Hưng and his ministers acknowledged the might of Ming army; the Lê ministers further viewing Japan as other Southeast Asian nations as "barbarians" and formally decided refused the Japanese lord's invitation.[69]

Later, the first son of Nguyễn Kim, (Nguyễn Uông) was assassinated by Trịnh Kiểm. Nguyễn Kim's second son, Nguyễn Hoàng, relocated to the south, became the Viceroy of Thuận Hoá province, founded the line of Nguyễn lords, and started a revolt against the reign of the Trịnh lords. As such, Đại Việt was divided for 232 years as the two lords fought each other in what is now known as the Trịnh–Nguyễn civil War.

Trịnh–Nguyễn contention

In 1620, Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên officially refused to send taxes to the court in Hanoi. A formal demand was made to the Nguyễn to submit to the authority of the court, and it was formally refused. In 1623 Trịnh Tùng died and was succeeded by his son Trịnh Tráng. Now Trịnh Tráng made a formal demand for submission, and again Nguyễn Phúc Nguyên refused. Finally in 1627 open warfare broke out between the Trịnh and the Nguyễn. For four months a large Trịnh army battled against the Nguyễn army but were unable to defeat them. The result of this war was that Vietnam had effectively been partitioned into northern and southern regions, with the Trịnh controlling most of the north and the Nguyễn controlling most of the south; the dividing line was the Gianh River in Quảng Bình Province. This border was very close to the Seventeenth parallel (in actuality the Bến Hải River located just to the south in Quảng Trị Province), which was imposed as the border between North Vietnam and South Vietnam during the Partition of Vietnam (1954–75).

While the Trịnh ruled over a much more populous territory, the Nguyễn had several advantages. First, they were on the defensive. Second, the Nguyễn were able to take advantage of their contacts with the Europeans, specifically the Portuguese, to purchase advanced European weapons and hire European military experts in fortifications. Third, the geography was favorable to them, as the flat land suitable for large organized armies is very narrow at this point of Vietnam; the mountains nearly reach to the sea.[70]

After the first assault, the Nguyễn built two massive fortified lines which stretched a few miles from the sea to the hills. The walls were built north of Huế near the city of Đồng Hới. The Nguyễn defended these lines against numerous Trịnh offensives which lasted till 1672.[70] The story from this time is that the great military engineer was a Vietnamese general who was hired away from the Trịnh court by the Nguyễn. This man is given the credit in Vietnam for the successful design of the Nguyễn walls. Against the walls the Trịnh mustered an army of 100,000 men, 500 elephants, and 500 large ships (Dupuy "Encyclopedia of Military History" pg. 596). The initial attacks on the Nguyễn wall was unsuccessful. The attacks lasted for several years.

In 1633 the Trịnh tried an amphibious assault on the Nguyễn to get around the wall. The Trịnh fleet was defeated by the Nguyễn fleet at the battle of Nhat-Le.[70] Around 1635 the Trịnh learned the Nguyễn and sought military aid from the Europeans. Trịnh Tráng hired the VOC to make European cannons and ships for the Royal army. In 1642–43, the Trịnh army attacked the Nguyễn walls. With the aid of the Dutch cannons, the Trịnh army broke through the first wall but failed to break through the second. At sea, the Trịnh, with their Dutch ships Kievit, Nachtegaels and Woekende Book were destroyed in a humiliating defeat by the Nguyễn fleet with their Chinese style galleys.[71][72][73][74][75] Trịnh Tráng staged yet another offensive in 1648 but at the battle of Truong Duc, the Royal army was badly beaten by the Nguyễn.[70] The new Lê king died around this time, perhaps as a result of the defeat. This now left the door open for the Nguyễn to finally go on the offensive.

The Nguyễn launched their own invasion of northern Vietnam in 1653. The Nguyễn army attacked north and defeated the weakened Royal army. Quảng Bình Province was captured. Then Hà Tĩnh Province fell to the Nguyễn army. In the following year, Trịnh Tráng died as Nguyễn forces made attacks into Nghệ An Province. Under a new Trịnh Lord, the capable Trịnh Tạc, the Royal army attacked the Nguyễn army and defeated it. The Nguyễn were fatally weakened by a division between their two top generals who refused to cooperate with each other. In 1656 the Nguyễn army was driven back all the way to their original walls. Trịnh Tạc tried to break the walls of the Nguyễn in 1661 but this attack, like so many before it, failed to break through the walls.

In 1672, the Trịnh army made a last effort to conquer the Nguyễn. The attacking army was under the command of Trịnh Tạc's son, Trịnh Căn, while the defending army was under the command of Nguyễn Phúc Tần's son Prince Nguyễn Phúc Thuận. The attack, like all the previous attacks on the Nguyễn walls, failed. This time the two sides agreed to a peace. With mediation supplied by the government of the Kangxi Emperor, the Trịnh and the Nguyễn finally agreed to end the fighting by making the Linh River the border between their lands (1673). Although the Nguyễn nominally accepted the Lê King as the ruler of Vietnam, the reality was, the Nguyễn ruled the south, and the Trịnh ruled the north. This division continued for the next 100 years. The border between the Trịnh and the Nguyễn was strongly guarded but peaceful. Despite the partition, both the two families claimed themselves loyal to the Royal family, and their territories were all counted as Đại Việt's land.

Tây Sơn rebellion

The stalemate between the Trịnh and the Nguyễn lords that began at the end of the 17th century did not, however, mark the beginning of a period of peace and prosperity. Instead the decades of continual warfare between the two families had left the ruists and peasantry in a weakened state, the victim of taxes levied to support the courts and their military adventures. Having to meet their tax obligations had forced many peasants off the land and facilitated the acquisition of large tracts by a few wealthy landowners, nobles, and scholar—officials. Because scholar—officials were exempted from having to pay a land tax, the more land they acquired, the greater was the burden that fell on those peasants who had been able to retain their land. In addition, the peasantry faced new taxes on staple items such as charcoal, salt, silk, and cinnamon, and on commercial activities such as fishing and mining. The disparate condition of the economy led to neglect of the extensive network of irrigation systems as well.

As they fell into disrepair, disastrous flooding and famine resulted, unleashing great numbers of starving and landless people to wander aimlessly about the countryside. The widespread suffering in North Vietnam led to numerous peasant revolts between 1730 and 1770, notable the peasant rebellion of Nguyễn Hữu Cầu from 1748 to 1751. Although the uprisings took place throughout the country, they were essentially local phenomena, breaking out spontaneously from similar local causes. The occasional coordination between and among local movements did not result in any national organization or leadership. Moreover, most of the uprisings were conservative, in that the leaders supported the restoration of the Lê dynasty. They did, however, put forward demands for land reform, more equitable taxes, and rice for all. Landless peasants accounted for most of the initial support for the various rebellions, but they were often joined later by craftsmen, fishermen, miners, and traders, who had been taxed out of their occupations. Some of these movements enjoyed limited success for a short time, but it was not until 1771 that any of the peasant revolts had a lasting national impact.

Dissatisfaction against two ruling families Trịnh and Nguyễn spread through out the country. In 1771, three brothers Nguyễn Nhạc, Nguyễn Lữ and Nguyễn Huệ in An Khê, Bình Định with local peasants support, revolted against the Nguyễn lord.[76][77][78] In 1773, the Tây Sơn captured Quy Nhơn fort in 1773, gave them financial and manpower support, thus made the rebellion and became widespread. In 1774, Trịnh army from the north launched an offensive against the Nguyễn. Unable to fight two-front war, Lord Nguyễn Phúc Thuần lost the control of Cochinchina, fled by ship to the Mekong delta. Nguyễn's capital Phú Xuân was captured by Trịnh lord. Nguyễn Phúc Thuần later was taken and executed by the Tây Sơn in 1777.[79] The remnant Nguyen led by Nguyễn Ánh with help from the French priest Pigneau de Behaine (Bá Đa Lộc),[80][81][82][83][84] he soon recruited his army by enlisted French, Cambodian troops and weapons, but mostly were defeated by the superior and numberior Tây Sơn rebels in four times, and Ánh went exiled in Siam.[85] The Tây Sơn rebellion were not content to simply conquer the southern provinces of the country.

End of the dynasty

In 1782, Trịnh Sâm died and passed the throne to his 5-year-old son Trịnh Cán instead of his 19-year-old son Trịnh Tông, who was demoted after his failed coup d'état attempt in 1780. Trịnh Sâm assigned Hoàng Tố Lý (also known as Hoàng Đình Bảo) as Cán's regent. Trịnh Tông allied with the Three Prefectures Army (Vietnamese: Tam phủ quân, Hán tự: 三府軍) to overthrow Trịnh Cán and kill Hoàng Tố Lý. The army then released the emperor's grandson Lê Duy Kỳ (also known as Lê Duy Khiêm) from imprisonment and forced the emperor to appoint him as the next successor. Trịnh Tông feared that army's power would grew stronger. He secretly ordered governors of the Four Provinces (Kinh Bắc, Sơn Nam, Hải Dương, Sơn Tây) to march into the capital and dismiss the Three Prefectures Army. However the plan was discovered by the army and Trịnh Tông had to cancel it.

Hoàng Tố Lý's subordinate Nguyễn Hữu Chỉnh, after hearing about Tố Lý's death, took refuge in Tây Sơn.

In 1786, king of Tây Sơn Nguyễn Nhạc wanted to recover the old territory of Nguyễn lords captured by the Trịnh. He ordered Nguyễn Huệ and Nguyễn Hữu Chỉnh to undertake the task. Nhạc warned Huệ not to attack Bắc Hà. However, Chỉnh convinced Huệ to do so, under the slogan "Destroy the Trịnh and aid the Lê" (Vietnamese: Diệt Trịnh phù Lê, Hán tự: 滅鄭扶黎) that would help them gain support from Bắc Hà people. Trịnh army and the Three Prefectures Army were quickly defeated. Trịnh Tông committed suicide. Emperor Cảnh Hưng died of old age shortly after and passed the throne to Lê Duy Kỳ (emperor Chiêu Thống).

Nguyễn Nhạc, after having heard of Nguyễn Huệ's insubordination, hastily marched to Thăng Long and ordered all Tây Sơn troops to withdraw. However they intentionally left Nguyễn Hữu Chỉnh behind. Chỉnh chased after them and then stayed in his hometown in Nghệ An.

After Tây Sơn's withdrawal, members of Trịnh clan, namely Trịnh Lệ and Trịnh Bồng, along with their supporters marched into Thăng Long and demanded Chiêu Thống to reinstall Trịnh lord. Chiêu Thống, whose father was killed by Trịnh Sâm, reluctantly agreed and assigned Trịnh Bồng as Prince of Yến Đô (Vietnamese: Yến Đô vương, Hán tự: 晏都王). Emperor Chiêu Thống then sent a secret order to Nguyễn Hữu Chỉnh to come and save him. In 1787, Nguyễn Hữu Chỉnh marched North, defeated Trịnh Bồng and his supporters, ended the 242 years rule of Trịnh clan.

In late 1787, Nguyễn Huệ, no longer served under Nguyễn Nhạc, sent Vũ Văn Nhậm to invade Bắc Hà under the pretense of punishing Nguyễn Hữu Chỉnh for insubordination. Nhậm captured and executed Chỉnh in January 1788, emperor Chiêu Thống fled to the east of Hong River. Vũ Văn Nhậm installed Lê Duy Cận as Country Supervisor (Vietnamese: Giám quốc, Hán tự: 監國) without Huệ's approval. Nguyễn Huệ accused Nhậm of treason and executed him, took over Bắc Hà.[86]

Lê Chiêu Thống sent envoy to the Imperial court of the Qing Empire to ask for aid against the Tây Sơn. The Qianlong Emperor of the Qing Empire under the pretense of restoring Lê dynasty dispatched a large force of 200,000 soldiers, to invade Northern Vietnam, captured the capital Thăng Long.

At the beginning of the war, Nguyễn Huệ's troops retreated to the South and refused to engage the Qing army. He raised a large army of his own and defeated the invader in the Lunar New year Eve of 1789. Chiêu Thống and the Royal family fled north into China, never to return. The Lê Dynasty finally ended after ruled Vietnam for 356 years. He went to Beijing where he was appointed a Chinese mandarin of the fourth rank in the Han Yellow Bordered Banner, while lower ranking loyalists were sent to cultivate government land and join the Green Standard Army in Sichuan and Zhejiang. They adopted Qing clothing and adopt the queue hairstyle, effectively becoming naturalized subjects of the Qing dynasty affording them protection against Vietnamese demands for extradition. Some Lê loyalists were also sent to Central Asia in Urumqi.[87][88] Modern descendants of the Lê monarch can be traced to southern Vietnam and Urumqi, Xinjiang.[89][90][91]

Culture, society, and science

Clothing and customs

After ending the Fourth Chinese domination of Vietnam, people of Đại Việt started to rebuild the country. The dress regulation for emperor and the bureaucracy was learned from the previous dynasties of Vietnam and Ming dynasty of China. In later Lê dynasty, cross-collared robe called áo giao lĩnh was popular among civilians.[92][93] A royal edict was issued by Vietnam in 1474 forbidding Vietnamese from adopting foreign languages, hairstyles and clothes like that of the Lao, Champa or the Ming "Northerners".[94]

Before 1744, people of both Đàng Ngoài (the north) and Đàng Trong (the south) wore giao lãnh y with thường (a kind of long skirt). Both male and female had loose long hair. In 1744, Lord Nguyễn Phúc Khoát of Đàng Trong (Huế) decreed that both men and women at his court wear trousers and a gown with buttons down the front. That the Nguyen Lords introduced ancient áo dài (áo ngũ thân). The members of the Đàng Trong court (southern court) were thus distinguished from the courtiers of the Trịnh Lords in Đàng Ngoài (Hanoi), who wore áo giao lĩnh with long skirts. The partition between two families over the country too long so caused the some major differences in Vietnamese dialect and culture between Northern and Southern Vietnamese.

Introduction of Christianity

European missionaries had occasionally visited Vietnam for short periods of time, with little impact, beginning in the early sixteenth century. Khâm định Việt sử Thông giám cương mục recorded first Christian missionarier name Inácio in the first year of Nguyên Hoà Emperor (1533) in Nam Định.[95] From 1580 to 1586, two Portuguese and French missionaries Luis de Fonseca and Grégoire de la Motte worked in Quảng Nam and Quy Nhơn region under lord Nguyễn Hoàng. After the Lê–Mạc War ended and peace was restored in 1593, more missionaries from Spain, Portugal France, Italy and Poland came to Vietname to spread Christianity. The best known of the early missionaries was Alexandre de Rhodes, a French Jesuit who was sent to Hanoi in 1627, where he quickly learned the language and began preaching in Vietnamese. Initially, Rhodes was well received by the Trinh court, and he reportedly baptized more than 6,000 converts; however, his success probably led to his expulsion in 1630. He is credited with perfecting a romanized system of writing the Vietnamese language (quốc ngữ), which was probably developed as the joint effort of several missionaries, including Rhodes. He wrote the first catechism in Vietnamese and published a Vietnamese-Latin-Portuguese dictionary; these works were the first books printed in quốc-ngữ. Quốc-ngữ was used initially only by missionaries; hán tự or chữ nôm continued to be used by the court and the bureaucracy. The French later supported the use of quốc ngữ, which, because of its simplicity, led to a high degree of literacy and a flourishing of Vietnamese literature. After being expelled from Vietnam, Rhodes spent the next thirty years seeking support for his missionary work from the Vatican and the French Roman Catholic hierarchy as well as making several more trips to Vietnam. However, since 1910, Latinized Quốc ngữ was adopted by the French governor as the main writing system of Vietnam,[96] while hán tự and nôm tự fell into declinine. Vietnamese Christianity developed and became stronger before it was cracked down on by Emperor Minh Mạng of the Nguyễn Dynasty in the 1820s.

Science and Philosophy

The Lê period was the continuously flourish era of Vietnamese scientific and Confucianism scholaric. Nguyễn Trãi was a 15th-century Lê official, author of geography book Dư địa chí, also was a Neo-Confucianist scholar. Lê Quý Đôn was a poet, encyclopedist, and government official, author of the geography book Phủ biên tạp lục. Hải Thượng Lãn Ông was a famous Vietnamese doctor and pharmacist with his full collection 28-volumes Hải Thượng y tông tâm lĩnh about traditional Vietnamese medicine. Matchlock firearms technology also spread from Mughal Empire to Đại Việt in 1516, and was adopted by the Lê army by the 1530s.

Literature and arts

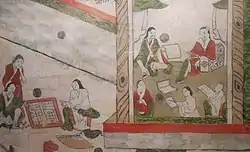

Written Chinese was the predominant writing language in Vietnam throughout the Lê dynasty, although written vernacular Vietnamese using chữ Nôm became increasingly popular in the 17th century.[4]:207 During the Lê dynasty, various forms of Vietnamese literature and art flourished, including poetry, painting, novels, hát tuồng, chèo, cải lương, and ca trù. Many writers wrote in Hán tự or chữ Nôm; for example, Nguyễn Du's The Tale of Kiều, Đoàn Thị Điểm's Chinh phụ ngâm, and Nguyễn Gia Thiều's Cung oán ngâm khúc.

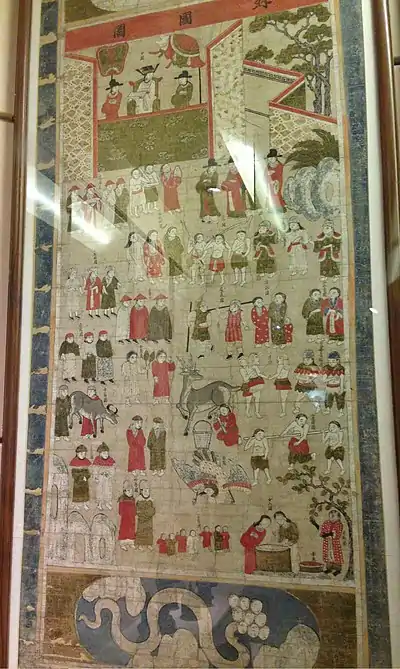

The art forms of that time prospered and produced items of great artistic value, despite the upheavals and wars. Woodcarving was especially highly developed and produced items that were used for daily use or worship. Many of these items can be seen in the National Museum in Hanoi.

Woodcut paintings "Thánh Cung vạn tuế" ("Long live his Imperial Majesty") from the 18th-century Nghệ An.

Woodcut paintings "Thánh Cung vạn tuế" ("Long live his Imperial Majesty") from the 18th-century Nghệ An. Ceramic stoneware vase, fifteenth century

Ceramic stoneware vase, fifteenth century Statue of Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva, crimson and gilded wood, Revival Lê dynasty, autumn of Bính Thân year (1656), from Bút Tháp pagoda in Bắc Ninh Province.

Statue of Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva, crimson and gilded wood, Revival Lê dynasty, autumn of Bính Thân year (1656), from Bút Tháp pagoda in Bắc Ninh Province. Wooden art pieces of the seventeenth century.

Wooden art pieces of the seventeenth century. Nghe (mythological beast) figurines, crimson and gilded wood, eighteenth century.

Nghe (mythological beast) figurines, crimson and gilded wood, eighteenth century.%252C_Lau_Thuong_Communale_house%252C_Phu_Tho_province%252C_17th_century_AD%252C_wood_-_Vietnam_National_Museum_of_Fine_Arts_-_Hanoi%252C_Vietnam_-_DSC04934.JPG.webp) Lion decorate in seventeenth century.

Lion decorate in seventeenth century..jpg.webp) Dragon of the Later Lê dynasty.

Dragon of the Later Lê dynasty. Buddhanandi statue of the Le dynasty.

Buddhanandi statue of the Le dynasty. Ceramic Lion bush , sixteenth century.

Ceramic Lion bush , sixteenth century. Royal dish of the Le dynasty.

Royal dish of the Le dynasty. Horse figure, 1720.

Horse figure, 1720. Celadon dish from Chu Dau, 15th century.

Celadon dish from Chu Dau, 15th century.

Education and imperial examination system

In late 1426, Lê Lợi held a small Confucian examination in Đông Kinh, graduated 30 tiến sĩ. From 1431, the court annually held Provincial and metropolitan exams were organized in three sessions. The first session took place in every province, consisted of three questions on the examinee's interpretation of the Four Books, and four on the Classics corpus. Everyone who passed the first session were called Sinh đồ and Hương cống. The second session took place in the capital one year later, and consisted of a discursive essay, a based Tang poetry, five critical judgments, and one in the style of an edict, an announcement and a memorial. Three days after that, the third session was held by the emperor, consisting of five essays on the Classics, historiography, and contemporary affairs. From 1486, every mandarin candidates must participated both first and second session to approve the chain. The Le's examination system reflected the Ming's imperial examination.[97] During the period from 1426 to 1527, the Lê dynasty held 26 Imperial examinations in the capital, graduated 989 tiến sĩ and 20 trạng nguyên.[98] By the 1750s, Neo-Confucianism were declining, the imperial examinations began having surplus graduates, downgrading quality of jinshi and mandarin, corruptions, the court prefer children of noble families to be mandarins that take check, thus made the downfall of Confucian examination system in Vietnam in the late 18th century until the established of Nguyễn dynasty.[99]

Scholars and administrators who graduated from the imperial examination system during the Lê dynasty include Nguyễn Bỉnh Khiêm, Nguyễn Thị Duệ, Phùng Khắc Khoan, Lê Quý Đôn, Lương Thế Vinh, and Nguyễn Đăng Đạo.

Foreign relations

China

In 1428, Lê Lợi established a tributary relationship with the Ming dynasty in exchange for the recognition and formal protection of his kingdom. Xuande Emperor gave Lê Lợi the title "An Nam Quốc Vương" (king of Annam) and recognized internal Vietnamese independence and sovereignty (which would last until 1526).[1][2][3][23] Also part of the tributary relationship was the responsibility of the Ming to provide external military support to the Lê state.[3] Ming support for the Lê against the Mạc uprising arrived in 1537.[3] After the 1540 surrender of the Mạc to the Ming, the Ming court ceremonially revoked the Mạc dynasty's status as an independent kingdom and reclassified it as a dutongshisi: a category only slightly higher than a chieftaincy.[3] After 1540, the Ming received tribute from both the Lê dynasty and the Mạc, a state of affairs that continued through the Qing dynasty.[3][23] From 1647, the Southern Ming reclassified Annam as an independent kingdom, giving Lê Duy Kỳ the title "An Nam Quốc Vương" (安南国王) again.[100] In 1667, the Kangxi Emperor of the Qing empire gave the title An Nam Quốc Vương to Viet king Lê Duy Vũ through a successful Vietnamese diplomatic mission.[101]

Other neighbors

Outside China, the Lê dynasty had its own tributary relationships with Panduranga, Lan Xang, Cambodia.[102]

Europe

Vietnamese historiography notes that contact between Vietnam and the Holy See or Vatican was established during the reign of emperor Lê Thế Tông (1572–1599) through a diplomacy letter in Classical Chinese that is held in a Vatican library in the modern day.[103]

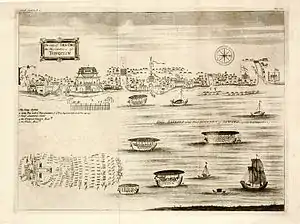

The seventeenth century was also a period in which European missionaries and merchants became a serious factor in Vietnamese court life and politics. Although both had arrived by the early sixteenth century, neither foreign merchants nor missionaries had much impact on Vietnam before the seventeenth century. The Portuguese, Dutch, English, and French had all established trading posts in Phổ Hiền by 1680. Fighting among the Europeans and opposition by the Vietnamese made the enterprises unprofitable, however, and all of the foreign trading posts were closed by 1800.

Economic development

Before 1527, the Imperial court restricted people for foreign trade, main focused on agriculture and local market, addition the period of political unstable from 1505 to 1527 made the country's economy quickly shrink down. There was series of severe famines in Hải Dương prefecture and Kinh Bắc prefecture (Bắc Ninh, Bắc Giang) occurred in 1517 to 1521 during the reign of Lê Tương Dực.[104] The sixteen-century political crisis caused severe damages to Vietnamese's agriculture and conscription required by incessant military campaigns, compounded by natural disasters, largely contributed to regular crop failures. Number of landless peasant grew quickly, causing a disproportionate surplus of unemployed labours in Northern Vietnam. After Mạc Đăng Dung gained power in 1527, he sought to restore the economy by encouraging these unemployed peasants into city and factories, pursuing massive handicraft industrial and sea trading, shifted the economy from mainly on farming to sea-traders from the Red River delta to the Eastern coast.[102] Vietnamese merchants and sailors formed together built medium-size ships in Hai Mon port (now Hai Phong) and quickly gained dominant on the South China sea trade route, mostly sailed from Japan to Malacca to sold silk and ceramic. Some of them eventually reached Egypt and Greece under Ottoman's rule around the 1570s.[102] After recaptured Dong Kinh in 1592, the Lê-Trịnh court acknowledge the benefits of oversea trading, continue encourages handicraft industrial and opened some international ports like Hoi An, Dong Kinh for the presence of foreign merchants. About 80% of the population were farmers and peasants; they worked on lands mostly were held by địa chủ or the landlords. The economy was devastated in some regions of the country due to two long civil war and unstable, however, in most part of the country which were unaffected area, peace were maintained for a long time, saw a rise of urbanization and pre-capitalism society in Vietnam around late 16th to 18th century.[102]

In contrast to the overpopulation Red river delta, Thuan Hoa and Quang Nam region were still less dense. Vietnamese people had begun settling in the conquered Cham land at least since the 1400s. After Nguyễn Hoàng appointed the governor of southern provinces in 1572, million people migrated to the south, resulted in new opened cities and harbors along the coastline. For centuries the Nguyễn's economy mostly depended on handicraft industrial and international trade.[105] Until the later 18th century, due to deadly epidemic, severe flood in Red River Delta, the immense corruption of the government and the rise of Tây Sơn peasant rebellion in Southern Vietnam, that later spread entire country, devastated most of the economy and international trading, played a important role for the collapse of the dynasty.

Đông Kinh and urban life

Đông Kinh, the capital of Vietnam since the 11th century, during the Later Lê Dynasty it was divided into 13 districts and 239 wards (with 36 main business-trading wards) and communes.[106][107] Dong Kinh since mid-1500s became the silk and ceramic manufacturing center of Southeast Asia. Vietnamese merchants exported to Ottoman Empire and Safavid Empire Tonkinese octagonal bottles with underglaze-cobalt decoration or dishes with peony sprays painted in underglaze-cobalt were considered as good as Chinese products.[102] Vietnamese ceramic from Bát Tràng villages produce famous high-quality pottery and dishes.

They [The Vietnamese] have porcelain and pottery-some of them great value-and these go from there to China to be sold. Tomé Pires, 1515

Chinese and Japanese traders came to Dong Kinh to buy both high quality silk and raw silk. Besides silk textiles were made by villages, majority of them were produced in state-owned factories in Dong Kinh, which produced for the Royal family, noblemen and foreigners.[102] In 1637, the Dutch successfully established commercial and diplomatic relations with Tonkin and maintained their trading station in the capital of Thăng Long (present-day Hanoi) until 1700. The lucrative Dutch ‘Vietnamese-silk-for-Japanese-silver trade‘ later also attracted the English and the French to Tonkin in 1672 and early 1682 respectively. The British imported Vietnamese silk around the 1670s, but not regularly. The city had a Chinatown, factories owned by Dutch, English companies along the Red river.[108] In 1594, the Imperial court allows the Western presence in the capital, encouraged Dutch, Spanish and British to open trading ports. In 1616, the British established a factory in Đông Kinh, but their business were ended in failure due to the pressures from the Lê court, and finally withdrew in 1720.[109] During the 17th and 18th century, Westerners commonly used the name Tonkin (from Đông Kinh) to refer to northern Vietnam, then ruled by the Trịnh lords (while Cochinchina was used to refer to Southern Vietnam, then ruled by the Nguyễn lords, and Annam, from the name of the former Chinese province was used to refer to Vietnam as a whole). Tonkin had been a major industrial factory and trading center in Asia until the 1730s.[110] The prosperity during the Le dynasty was described through the urbanization in Tonkin through Western narratives: "...Cachao (Dong Kinh) probably had 200,000 houses. The city size was some larger than some the largest cities in Europe but similar size to other major Asian cities. It lies along the Red river...there are 36 stone-paved major streets, many people from areas to foreigners such as Chinese, Japanese, English held their business companies, factories and stores here...the Emperor has three small but magnificent palaces, mostly built by red wood and terracotta bricks, surrounded by 15-feet height wall, and its main gate never opens expect when the Emperor wants to go outside. The Trinh lord and his families live in 30-meter height Ngũ Long castle, near Tạ Vọng lake, can be seen the highest from the Red river..."[111]

In 1612, Joseon army encountered a Vietnamese merchant ship from Tonkin wrecked in Jeju Island carried a lot of treasures and money. The Koreans killed all sailors, looted treasures on board then falsely reported the ship "was a pirate ship".[112]

However, by the last quarter of the 1600s, Tonkin was no longer a profitable trading place. Vietnamese silk no longer reaped a handsome profit in Japan and Vietnamese ceramics proved unmarketable in the insular Southeast Asian markets. In Tonkin, trading conditions also deteriorated rapidly. Subsequently, natural disasters ravaged the economy of the country and a wave of successive famines discouraged local craftsmen from producing goods for export. Worse still, after the protracted civil war with the southern Vietnamese kingdom of Quinam (or Đàng Trong) ended in 1672, the Tonkinese rulers seemed to be more indifferent towards foreign trade as they were no longer in urgent need of a supply of weapons from the Westerners. Bearing in mind their long-term strategy, especially the prospect of opening up trading relations with China, the Dutch still wanted to maintain their Tonkin trade despite its current unprofitable state, perceiving that it would be extremely difficult to re-establish the relationship with Tonkin once they left the country.[102] Despite the Dutch persistence, the relationship between the VOC and Tonkin deteriorated rapidly during the last two decades of the seventeenth century, especially after Chúa (Lord) Trịnh Căn (r. 1682–1709) succeeded to the throne.[102]

Hội An

The area of Quảng Nam river original was part of Champa kingdoms and was annexed by Đại Việt during Emperor Thánh Tông 's reign. It was opened for foreign merchants trade and settlement. In 1535 Portuguese explorer and sea captain António de Faria, coming from Da Nang, tried to establish a major trading centre at the port village of Faifo.[113] Hội An was founded as a trading port by the Nguyễn Lord Nguyễn Hoàng in 1570. The Nguyễn lords were far more interested in commercial activity than the Trịnh lords who ruled the north. As a result, Hội An flourished as a trading port and became the most important trade port on the East Vietnam Sea. Captain William Adams, the English sailor and confidant of Tokugawa Ieyasu, is known to have made one trading mission to Hội An in 1617 on a Red Seal Ship.[114] The early Portuguese Jesuits also had one of their two residences at Hội An.[115] In 1640, Nguyễn lord Nguyễn Phúc Lan ordered to close all Dutch stores and factories in Hội An, ban the Dutch for trading in Cochinchina because he suspected the VOC allying with the Trịnh lord in the north.[116] In the 17th century, Polish Jesuit missionary Wojciech Męciński was believed to visited Hội An.[117]

In the 18th century, Hội An was considered by Chinese and Japanese merchants to be the best destination for trading in all of Southeast Asia, even Asia. Trading activities and handicraft manufacturing had been shifted from Tonkin to Hội An.[102] The city also rose to prominence as a powerful and exclusive trade conduit between Europe, China, India, and Japan, especially for the ceramic industry. Shipwreck discoveries have shown that Vietnamese and Asian ceramics were transported from Hội An to as far as Sinai, Egypt.[118]

Hội An's importance waned sharply at the end of the 18th century because of the collapse of Nguyễn rule (thanks to the Tây Sơn Rebellion – which was opposed to foreign trade). Then, with the triumph of Emperor Gia Long, he repaid the French for their aid by giving them exclusive trade rights to the nearby port town of Đà Nẵng. Đà Nẵng became the new centre of trade (and later French influence) in central Vietnam while Hội An was a forgotten backwater. Local historians also say that Hội An lost its status as a desirable trade port due to silting up of the river mouth. The result was that Hội An remained almost untouched by the changes to Vietnam over the next 200 years. The efforts to revive the city were only done by a late Polish architect and influential cultural educator, Kazimierz Kwiatkowski, who finally brought back Hội An to the world. There is still a statue for the late Polish architect in the city, and remains a symbol of the relationship between Poland and Vietnam, which share many historical commons despite its distance.[119]

Gia Định

Beginning in the early 17th century, colonization of the area by Vietnamese settlers gradually isolated the Khmer of the Mekong Delta from their brethren in Cambodia proper and resulted in their becoming a minority in the delta. In 1623, King Chey Chettha II of Cambodia (1618–28) allowed Vietnamese refugees fleeing the Trịnh–Nguyễn civil war in Vietnam to settle in the area of Prey Nokor and to set up a customs house there.[120] Increasing waves of Vietnamese settlers, which the Cambodian kingdom could not impede because it was weakened by war with Thailand, slowly Vietnamized the area. In time, Prey Nokor became known as Saigon. Prey Nokor was the most important commercial seaport to the Khmers. The loss of the city and the rest of the Mekong Delta cut off Cambodia's access to the East Sea. Subsequently, the only remaining Khmers' sea access was south-westerly at the Gulf of Thailand e.g. at Kampong Saom and Kep.

In 1698, Nguyễn Hữu Cảnh, a Vietnamese noble and explorer, was sent by the Nguyễn rulers of Huế by ship[121] to establish Vietnamese administrative structures in the area, thus detaching the area from Cambodia, which was not strong enough to intervene. He is often credited with the expansion of Saigon into a significant settlement of Kinh and Hoa people. A large Vauban citadel called Gia Định was built[122] by Victor Olivier de Puymanel, one of the Nguyễn Ánh's French mercenaries. The citadel was later destroyed by the French following the Battle of Kỳ Hòa (see Citadel of Saigon). Initially called Gia Dinh, the Vietnamese city became Saigon in the 18th century. At the time, the population of Gia Định was around 200,000 people with 35,000 households.[123]

List of emperors

The following is a list of emperors of the Lê dynasty from 1428 to 1527.

| Temple name | Posthumous name | Personal name | Lineage | Reign | Regnal name | Tomb | Events | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Thái Tổ | Thống Thiên Khải Vận Thánh Đức Thần Công Duệ Văn Anh Vũ Khoan Minh Dũng Trí Hoàng Nghĩa Chí Minh Đại Hiếu Cao Hoàng đế (統天啟運聖德神功睿文英武寬明勇智弘義至明大孝高皇帝) | Lê Lợi (黎利) | Lam Sơn rebellion | 1429–1433 | Thuận Thiên (順天) | Vĩnh Tomb, Lam Sơn | Founder of the Lê dynasty, recognized by the Ming dynasty as legitimate ruler of Đại Việt in 1431.[124] |

.jpg.webp) |

Thái Tông | Kế Thiên Thể Đạo Hiển Đức Thánh Công Khâm Minh Văn Tư Anh Duệ Triết Chiêu Hiến Kiến Trung Văn Hoàng đế (繼天體道顯德功欽明文思英睿仁哲昭憲建中文皇帝) | Lê Nguyên Long (黎元龍) | Son | 1433–42 (2) | Thiệu Bình (紹平 1434 – 1439) , Đại Bảo (大寶 1440 – 1442) | Hựu Lăng, Lam Kinh | |

.jpg.webp) |

Nhân Tông | Khâm Văn Nhân Hiếu Tuyên Minh Thông Duệ Tuyên Hoàng đế (欽文仁孝宣明聰睿宣皇帝) | Lê Bang Cơ (黎邦基) | Son | 1442–1459 (3) | Thái Hòa (太和 1443 – 1453), Diên Ninh (延寧 1454 – 1459) | Mục Lăng | The youngest emperor, murdered by Duke Lê Nghi Tân |

|

Thánh Tông | Sùng Thiên Quảng Vận Cao Minh Quang Chính Chí Đức Đại Công Thánh Văn Thần Vũ Đạt Hiếu Thuần Hoàng đế (崇天廣運高明光正至德大功聖文神武達孝淳皇帝) | Lê Tư Thành (黎思誠) | Son | 1460–97 (4) | Quang Thuận (光順 1460–1469), Hồng Đức (洪德 1470–1497) | Chiêu Lăng | Annexed Champa and Northwest Lao |

.jpg.webp) |

Hiến Tông | Thể Thiên Ngưng Đạo Mậu Đức Chí Nhân Chiêu Văn Thiệu Vũ Tuyên Triết Khâm Thành Chương Hiếu Duệ Hoàng Đế (體天凝道懋德至仁昭文紹武宣哲欽聖彰孝睿皇帝) | Lê Tranh | Son | 1497–1504 (5) | Cảnh Thống (景統) | Dụ Lăng | Declining of the dynasty |

| Túc Tông | Chiêu Nghĩa Hiển Nhân Ôn Cung Uyên Mặc Hiếu Doãn Cung Khâm Hoàng đế (昭義顯仁溫恭淵默惇孝允恭欽皇帝) | Lê Thuần (黎㵮) | Son | 1504–1505 (6) | Tự Hoàng (嗣皇) | Kính Lăng | Six-month emperor (17 July 1504 – 12 January 1505) | |

_-_Scott_Semans_01.jpg.webp) |

Uy Mục | Mẫn Lệ công (愍厲公) | Lê Tuấn (黎濬) | Younger brother | 1504–1509 (7) | Đoan Khánh (端慶) | An Lăng | Evil king/Quỷ vương (鬼王) |

.jpg.webp) |

Tương Dực | Linh Ẩn vương (靈隱王) | Lê Oanh (黎瀠) | Cousin (son of Duke Lê Tân) | 1509–1516 (8) | Hồng Thuận (洪順) | Nguyên Lăng | Rebellion ursupred the throne, assassinated by general Trịnh Duy Sản |

.jpg.webp) |

Chiêu Tông | Thần Hoàng đế (神皇帝) | Lê Y (黎椅) | cousin | 1517–1522 (9) | Quang Thiệu (光紹) | Vĩnh Hưng Lăng | Murdered by Mạc Đăng Dung in 1525 |

|

Cung Hoàng | Cung Hoàng đế (恭皇帝) | Lê Xuân (黎椿) | Brother of Chiêu Tông | 1522–1527 (10) | Thống Nguyên (統元) | Hoa Dương lăng | Hanged by himself, End of the Lê Dynasty. |

The following is a list of emperors of the Revival Lê Dynasty, which continued the Lê Dynasty from 1533 after Mạc Đăng Dung usurped the throne and occupied the capital of Thăng Long for 55 years.

| Temple name | Posthumous name | Personal name | Lineage | Reign | Regnal name | Tomb | Events | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Trang Tông | Dụ Hoàng đế (裕皇帝) | Lê Ninh (黎寧) | descendant of Lê Lợi | 1533–1548 (11) | Nguyên Hòa (元和) | Cảnh lăng | Jiajing Emperor of Ming dynasty sent 110,000 soldiers to help the Lê family restore the throne in 1536 to 1540. |

| Trung Tông | Vũ Hoàng đế (武皇帝) | Lê Huyên (黎暄) | Son | 1548–1556 (12) | Thuận Bình (顺平) | Diên lăng | Lê army recaptured Thuận Hóa and Quảng Nam from Mạc in 1553. | |

| Anh Tông | Tuấn Hoàng đế (峻皇帝) | Lê Duy Bang (黎維邦) | Son | 1556–1573 (13) | Thiên Hựu (天祐 1557), Chính Trị (正治 1558 – 1571), Hồng Phúc (洪福 1572) | Bố Vệ lăng | The rise of Nguyễn clan in Thuận Hóa and Quảng Nam. | |

| Thế Tông | Tích Thuần Cương Chính Dũng Quả Nghị Hoàng đế (積純剛正勇果毅皇帝) | Lê Duy Đàm (黎維潭) | Son | 1573–99 (14) | Gia Thái (嘉泰 1573 – 1577), Quang Hưng (光興 1578 – 1599) | Hoa Nhạc lăng | Recaptured Thăng Long, the Mạc dynasty collapsed. | |

| Kính Tông | Hiển Nhân Dụ Khánh Tuy Phúc Huệ Hoàng đế (显仁裕庆绥福惠皇帝),[125] Giản Huy Hoàng đế (簡輝皇帝) | Lê Duy Tân (黎維新) | Son | 1599–1619 (15) | Thận Đức (慎德 1600 – 1601), Hoằng Định (弘定 1601 – 1619) | Trịnh Lords held most powers of the Lê court. | ||

| Thần Tông | Uyên Hoàng đế (淵皇帝) | Lê Duy Kỳ (黎維祺) | Son | 1619–1643, 1649–1662 (16) | Vĩnh Tộ (永祚 9/1619 – 1628), Đức Long (德隆 1629 – 1634), Dương Hòa (陽和 1635 – 9/1643), Khánh Đức (慶德 10/1649 – 1652), Thịnh Đức (盛德 1653 – 1657), Vĩnh Thọ (永壽 1658 – 8/1662), Vạn Khánh (萬慶 9/1662) | Quần Ngọc lăng | Has 11 Consorts with difference nationalities, 4 foster children: Princess Lê Thị Ngọc Duyên, second crown prince Lê Duy Tào, prince Lê Duy Lương and Các Hắc Sinh (Willem Carel Hartsinck)[126] (1638–1689), the Dutch tradesman who deputized the Dutch East India Company in Taiwan. | |

| Chân Tông | Thuận Hoàng đế (順皇帝) | Lê Duy Hựu (黎維祐) | Son | 1643–1649 (17) | Phúc Thái (福泰) | Hoa Phố lăng | The Lê court hired 3 VOC ships to helped battle against Nguyễn Lord in Cochinchina but were defeated in 1643. | |

| Huyền Tông | Mục Hoàng đế (穆皇帝) | Lê Duy Vũ (黎維禑) | Son of Thần Tông, younger brother of Chân Tông | 1662–1671 (18) | Cảnh Trị (景治) | An Lăng | The emperor passed away when he was only 17 | |

| Gia Tông | Khoan Minh Mẫn Đạt Anh Quả Huy Nhu Khắc Nhân Đốc Nghĩa Mỹ Hoàng đế (寬明敏達英果徽柔克仁篤義美皇帝) | Lê Duy Cối (黎維禬) | Son of Thần Tông | 1671–1675 (19) | Dương Đức (陽德 1672 – 1674), Đức Nguyên (德元 1674 – 1675) | Phúc An lăng | The emperor passed away when he was 15 because cholera | |

|

Hy Tông | Chương Hoàng đế (章皇帝) | Lê Duy Cáp (黎維祫) | Son of Thần Tông | 1675–1705 (20) | Vĩnh Trị (永治 1676 – 1680), Chính Hoà (正和 1680 – 1705) | Phú lăng | War with the Nguyễn Lords in Cochinchina over, the remnant Mạc and Bầu lords were total defeated. |

| Dụ Tông | Thuần Chính Huy Nhu Ôn Giản Từ Tường Khoan Huệ Tôn Mẫu Hòa Hoàng đế (純正徽柔溫簡慈祥寬惠遜敏和皇帝) | Lê Duy Đường (黎維禟) | Son of Hy Tông | 1705–1729 (21) | Vĩnh Thịnh (永盛 1706 – 1719), Bảo Thái (保泰 1720 – 1729) | Kim Thạch | The Lê court recognized the Manchu Qing legitimates over China, Kangxi Emperor sent envoy and gave the title An Nam quốc vương 安南国王 (King of Annam) for Dụ Tông in 1718.[127] | |

| Duệ Tông | Hôn Đức công (昏德公), Thời Hoàng Đế (萬恩皇帝) | Lê Duy Phường (黎簡皇) | Son | 1732–1735 (22) | Vĩnh Khánh (永慶) | Kim Lũ | Was ascended the throne by Lord Trịnh Giang. | |

| Thuần Tông | Giản Hoàng đế (簡皇帝) | Lê Duy Tường (黎維祥) | Son of Dụ Tông | 1732–1735 (23) | Long Đức (龍德) | Bình Ngô Lăng | Poisoned by Trịnh Giang in 1735. | |

| Ý Tông | Ôn Gia Trang Túc Khải Túy Minh Mẫn Khoan Hồng Uyên Duệ Huy Hoàng đế (溫嘉莊肅愷悌通敏寬洪淵睿徽皇帝) | Lê Duy Thận (黎維祳) | Son of Thuần Tông | 1735–1740 (24) | Vĩnh Hựu (永佑) | Phù Lê lăng | The last retired emperor of Vietnam. | |

.jpg.webp) |

Hiển Tông | Vĩnh Hoàng đế (永皇帝) | Lê Duy Diêu (黎維祧) | First son of Thuần Tông | 1740–1786 (25) | Cảnh Hưng (景興) | Bàn Thạch lăng | Trịnh Giang was overthrew. Prince Lê Duy Mật even rebelled against the Trinh family but was suppressed quickly. |

|

Mẫn Hoàng đế (愍皇帝) | Lê Duy Kỳ (黎維祁) | Grandson of Hiển Tông | 1786–1789 (26) | Chiêu Thống (昭統) | Hoa Dương lăng | The last Emperor of the Later Lê Dynasty. | |

See also

Notes

- The use of the Classical Chinese language in documents and correspondences is distinct from the use of the Chữ Nôm writing system for the Vietnamese language.

- Especially when referring to the dynasty and era.

- Especially when referring to the family.

Citations

- Le Loi at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Womack, B. (2012). "Asymmetry and China's Tributary System". The Chinese Journal of International Politics. 5 (1): 37–54. doi:10.1093/cjip/pos003. ISSN 1750-8916.

- Baldanza, Kathlene (2014). "Perspectives on the 1540 Mac Surrender to the Ming". Asia Major. 27 (2): 115–146. JSTOR 44740553.

- Holcombe, Charles (2017). A History of East Asia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107118737.

- J. Gordon Melton, Martin Baumann (21 September 2010). Religion of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of beliefs and practices. p. 426. ISBN 9781598842043. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- Taouti 1985, pp. 197–198

- Đại Việt's Office of History 1993, pp. 509.

- "Open Doors International : Vietnam". Archived from the original on 2007-12-14. Retrieved 2007-03-29.

- Asia: Local Studies / Global Themes - Volume 3 Hue-Tam Ho Tai - 2001 - Page 91 "... an anti-Ming resistance — the Lam Son uprising, begun in 1418 — and the two men became the movement's key exponents. As emperor (1428-33), Le Loi would retain Nguyen Trai as his chief official; thereafter, their relationship was made ..."

- Lonely Planet Vietnam 10 -Nick Ray, Yu-Mei Balasingamchow, Iain Stewart - 2009 Page 30 "In 1418 wealthy philanthropist Le Loi sparked the Lam Son Uprising by refusing to serve as an official for the Chinese Ming dynasty. By 1428, local rebellions had erupted in several regions and Le Loi travelled the countryside to rally ..."

- H. K. Chang - From Movable Type Printing to the World Wide Web 2007 Page 128 "However, in 1418, another leader, Lê Lợi, staged an uprising, which led in 1428 to the establishment of the Lê dynasty, from which time Vietnam broke free of China and became independent".

- Ngọc Đĩnh Vũ Hào kiệt Lam Sơn: trường thiên tiểu thuyết lịch sử Volume 1 - 2003 "The Lam Sơn uprising, 1418-1428, is one of the greatest historical events in Vietnamese history, when a small country tried to gain independence from the firm grab of a bigger neighbor".

- Laurel Kendall Vietnam: Journeys of Body, Mind, and Spirit 2003- Page 27 "Le Loi led a successful ten,year (1418,1428) uprising against the Chinese. According to legend, Le Loi returned the sword that gave him victory to Hoan Kiem Lake (now the center of Hanoi), where it was retrieved by a giant turtle".

- Đào Duy Anh 2005, History of Vietnam by period, p 92

- Ming Shilu, thirteenth year of Yongle, vol. 196, pp 659《卷一百九十六,永樂十六年春正月甲寅條。這裡參考》

- Chan Chung Jin, p. 149

- Le Loi. The Encycloaedia Britannica. Micropedia, Volume VI, 15th Edition. ISBN 0-85229-339-9

- Trần Trọng Kim, Việt Nam sử lược, vol. I, part. III, sec. XIV(1418 – 1427)

- History of Ming, 王通传

- Trần Trọng Kim (2005). Việt Nam sử lược (in Vietnamese). Ho Chi Minh City: Ho Chi Minh City General Publishing House. pp. 212–213.

- Shih-shan Henry Tsai (1996). The Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty. SUNY Press. pp. 15–. ISBN 978-0-7914-2687-6.

- Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, University of Tokyo's Toyo Cultural Research Institute, p,546-548

- Baldanza, Kathlene (2016). Ming China and Vietnam: Negotiating Borders in Early Modern Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 204–210. doi:10.1017/cbo9781316440551.013. ISBN 978-1-316-44055-1.

- Việt Nam sử lược, p. 96.

- Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, pp 361.

- "...Our Thái tổ majesty just had retaken the Tianxia, the country was not recovered, and Hãn, Xảo wanted to conspired against the court...", Nguyễn Trực 1441

- "Lê, Lợi King of Vietnam 1385-1433". worldcat.

- Theobald

- Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư, Ngô Sĩ Liên, 1993, volume XI, p. 391

- Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư, Ngô Sĩ Liên , 1993, volume XI, p. 392

- Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư, Ngô Sĩ Liên, 1993, volume XI, p. 397–403.

- ereka.vn (13 April 2018). "Nomadic people in Vietnamese history".

- Vietnam, Trials and Tribulations of a Nation D. R. SarDesai, ppg 35–37, 1988

- Tsai (1996), The Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty (Ming Tai Huan Kuan), p. 15, at Google Books

- Rost (1887), Miscellaneous papers relating to Indo-China: reprinted for the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society from Dalrymple's "Oriental Repertory," and the "Asiatic Researches" and "Journal" of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Volume 1, p. 252, at Google Books

- Rost (1887), Miscellaneous papers relating to Indo-China and Indian archipelage: reprinted for the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. Second Series, Volume 1, p. 252, at Google Books

- Wade 2005, p. 3785/86

- "首页 > 06史藏-1725部 > 03别史-100部 > 49-明实录宪宗实录-- > 203-大明宪宗纯皇帝实录卷之二百十九". 明實錄 (Ming Shilu) (in Chinese). Retrieved 26 July 2013.

- Wade 2005, p. 2078/79

- Leo K. Shin (2007). "Ming China and Its Border with Annam". In Diana Lary (ed.). The Chinese State at the Borders (illustrated ed.). UBC Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0774813334. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- "首页 > 06史藏-1725部 > 03别史-100部 > 49-明实录宪宗实录-- > 106-明宪宗纯皇帝实录卷之一百六". 明實錄 (Ming Shilu) (in Chinese). Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- Tsai (1996), The Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty (Ming Tai Huan Kuan), p. 16, at Google Books

- Tsai (1996), The Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty (Ming Tai Huan Kuan), p. 245, at Google Books

- Roof 2011, p. 1210.

- Schliesinger 2015, p. 18.

- Manlch, M.L. (1967) History of Laos, pages 126-129.

- Ming Shilu, volume 3, p. 111

- Đại Việt sử ký toàn thư, Ngô Sĩ Liên 1993, volume XIII

- Trần Trọng Kim, Việt Nam sử lược, p. 102

- Đại Việt's Office of History 1993, pp. 526–527.

- Đại Việt's Office of History 1993, pp. 541–543

- Đại Việt's Office of History 1993, p. 544

- Đại Việt's Office of History 1993, pp. 566–568.

- Đại Việt's Office of History 1993, pp. 568–569.