Lake Powell

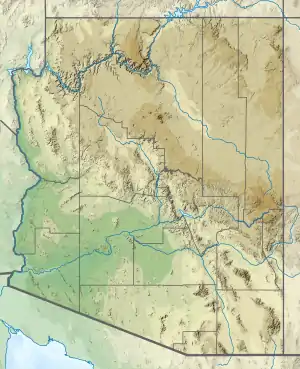

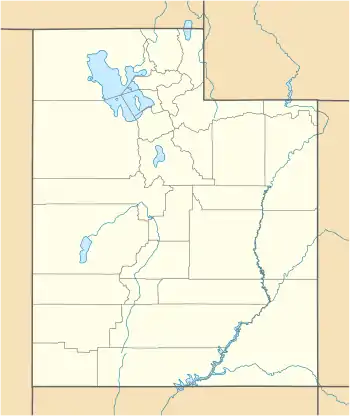

Lake Powell is a man-made reservoir on the Colorado River in Utah and Arizona, United States. It is a major vacation spot visited by approximately two million people every year. It is the second largest man-made reservoir by maximum water capacity in the United States behind Lake Mead, storing 24,322,000 acre feet (3.0001×1010 m3) of water when full. However, due to high water withdrawals for human and agricultural consumption, and because of subsequent droughts in the area, Lake Mead has fallen below Lake Powell in size several times during the 21st century in terms of volume of water, depth and surface area.

| Lake Powell | |

|---|---|

| |

Lake Powell  Lake Powell  Lake Powell | |

| Location | Utah and Arizona, United States |

| Coordinates | 36°56′10″N 111°29′03″W (Glen Canyon Dam) |

| Type | Reservoir |

| Primary inflows | |

| Primary outflows | Colorado River |

| Catchment area | 280,586 km2 (108,335 sq mi) |

| Basin countries | United States |

| Managing agency | National Park Service |

| Built | September 13, 1963 |

| Max. length | 186 mi (299 km) |

| Max. width | 25 mi (40 km) (maximum) |

| Surface area | 161,390 acres (65,310 ha) |

| Average depth | 132 ft (40 m) |

| Max. depth | 583 ft (178 m) |

| Water volume | |

| Residence time | 7.2 years |

| Shore length1 | 3,057 km (1,900 mi) |

| Surface elevation |

|

| Website | www |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. | |

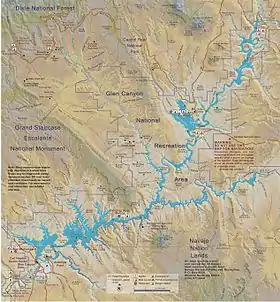

Lake Powell was created by the flooding of Glen Canyon by the Glen Canyon Dam, which also led to the 1972 creation of Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, a popular summer destination of public land managed by the National Park Service. The reservoir is named for explorer John Wesley Powell, a one-armed American Civil War veteran who explored the river via three wooden boats in 1869. It primarily lies in parts of Garfield, Kane, and San Juan counties in southern Utah, with a small portion in Coconino County in northern Arizona. The northern limits of the lake extend at least as far as the Hite Crossing Bridge.

Lake Powell is a water storage facility for the Upper Basin states of the Colorado River Compact (Colorado, Utah, Wyoming and New Mexico). The Compact specifies that the Upper Basin states are to provide a minimum annual flow of 7,500,000 acre feet (9.3 km3) to the Lower Basin states (Arizona, Nevada, and California).

History

In the 1940s and early 1950s, the United States Bureau of Reclamation planned to construct a series of Colorado River dams in the rugged Colorado Plateau province of Colorado, Utah, and Arizona. Glen Canyon Dam was born of a controversial damsite the Bureau selected in Echo Park, in what is now Dinosaur National Monument in Colorado. A small but politically effective group of objectors, led by David Brower of the Sierra Club, succeeded in defeating the Bureau's bid, citing Echo Park's natural and scenic qualities as too valuable to submerge. By agreeing to a relocated damsite near Lee's Ferry between Glen and Grand Canyons, however, Brower did not realize what he had gambled away. At the time, Brower had not actually been to Glen Canyon. When he later saw Glen Canyon on a river trip, Brower discovered that it had the kind of scenic, cultural, and wilderness qualities often associated with America's national parks.[2] Over 80 side canyons in the colorful Navajo Sandstone contained clear streams, abundant wildlife, arches, natural bridges, and numerous Native American archeological sites. By then, however, it was too late to stop the Bureau and its commissioner Floyd Dominy from building Glen Canyon Dam. Brower believed the river should remain free, and would forever after consider the loss of Glen Canyon his life's ultimate disappointment.[3]

Glen Canyon Dam was built to solve the downstream delivery obligations of the Upper Basin states. Lake Powell is an "aquatic bank" built to fulfill the terms of the "Compact Calls" of Lower Basin. If the Compact had required the Upper Basin to deliver half the flow of the Colorado in low water years, rather than a fixed amount, the burden of drought would have been spread equally between the basins and there would have been no need to build the dam. It's ironic that the lake is named after John Wesley Powell, who planned to settle the West based on the facts of hydrology, not politics.[4]

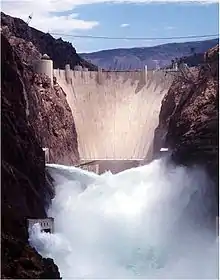

Construction on Glen Canyon Dam began with a demolition blast keyed by the push of a button by President Dwight D. Eisenhower at his desk in the Oval Office on October 1, 1956. The first blast started clearing tunnels for water diversion. On February 11, 1959, water was diverted through the tunnels so dam construction could begin. Later that year, the bridge was completed, allowing trucks to deliver equipment and materials for the dam, and also for the new town of Page, Arizona.

Concrete placement started around the clock on June 17, 1960. The last bucket of concrete was poured on September 13, 1963. Over 5 million cubic yards (4,000,000 m³) of concrete make up Glen Canyon Dam. The dam is 710 feet (216 m) high, with the surface elevation of the water at full pool being approximately 3700 feet (1100 m). Construction of the dam cost $155 million, and 18 lives were lost in the process. From 1970 to 1980, turbines and generators were installed for hydroelectricity. On September 22, 1966, Glen Canyon Dam was dedicated by Lady Bird Johnson.

Upon completion of Glen Canyon Dam on September 13, 1963, the Colorado River began to back up, no longer being diverted through the tunnels. The newly flooded Glen Canyon formed Lake Powell. Sixteen years elapsed before the lake filled to the 3,700 feet (1,100 m) level, on June 22, 1980. The lake level fluctuates considerably depending on the seasonal snow runoff from the Rocky Mountains.[5][6][7] The all-time highest water level was reached on July 14, 1983, during one of the heaviest Colorado River floods in recorded history, in part influenced by a strong El Niño event. The lake rose to 3,708.34 feet (1,130.30 m) above sea level, with a water content of 25,757,086 acre feet (31.770898 km3).[8]

Colorado River flows have been below average since 2000, leading to lower lake levels. In winter 2005 (before the spring run-off) the lake reached its lowest level since filling, an elevation of 3,555.10 feet (1,083.59 m)[9] above sea level, which was approximately 150 feet (46 m) below full pool. Since 2005, the lake level has slowly rebounded, although it has not filled completely since then. Summer 2011 saw the third largest June and the second largest July runoff since the closure of Glen Canyon Dam, and the water level peaked at nearly 3,661 feet (1,116 m), 77 percent of capacity, on July 30.[10] However, water years 2012 and 2013 were, respectively, the third and fourth-lowest runoff years recorded on the Colorado River. By April 9, 2014, the lake level had fallen to 3,574.31 feet (1,089.45 m), largely erasing the gains made in 2011.[11]

Colorado River levels returned to normal during water years 2014 and 2015 (pushing the lake to 3,606 feet (1,099 m) by the end of water year 2015.[12] The Bureau of Reclamation in 2014 reduced the Lake Powell release from 8.23 to 7.48 million acre-feet, for the first time since the lake filled in 1980. This was done due to the "equalization" guideline which stipulates that an approximately equal amount of water must be retained in both Lake Powell and Lake Mead, in order to preserve hydro-power generation capacity at both lakes. This resulted in Lake Mead declining to the lowest level on record since the 1930s.

In August 2020 Lake Powell was at an elevation of 3,599.72 feet (1,097.19 m) which is 100 feet (30 m) from full pool, and is 48% of full capacity. At that elevation it was storing 11.72 (14,456 trillion litres).[13]

Climate

These data are for the Wahweap climate station on Lake Powell just south of the Utah-Arizona border (Years 1961 to 2012).

| Climate data for Wahweap, AZ | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 69 (21) |

78 (26) |

85 (29) |

94 (34) |

104 (40) |

110 (43) |

120 (49) |

115 (46) |

105 (41) |

96 (36) |

80 (27) |

70 (21) |

120 (49) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 47.2 (8.4) |

53.8 (12.1) |

63.0 (17.2) |

72.8 (22.7) |

83.8 (28.8) |

94.1 (34.5) |

98.8 (37.1) |

95.7 (35.4) |

87.7 (30.9) |

73.7 (23.2) |

58.3 (14.6) |

47.1 (8.4) |

73.0 (22.8) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 26.9 (−2.8) |

31.8 (−0.1) |

37.8 (3.2) |

44.6 (7.0) |

54.9 (12.7) |

64.1 (17.8) |

71.3 (21.8) |

69.3 (20.7) |

60.7 (15.9) |

48.9 (9.4) |

36.9 (2.7) |

27.4 (−2.6) |

47.9 (8.8) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −2 (−19) |

4 (−16) |

21 (−6) |

16 (−9) |

29 (−2) |

40 (4) |

48 (9) |

51 (11) |

36 (2) |

24 (−4) |

15 (−9) |

3 (−16) |

−2 (−19) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.59 (15) |

0.56 (14) |

0.63 (16) |

0.37 (9.4) |

0.36 (9.1) |

0.17 (4.3) |

0.51 (13) |

0.75 (19) |

0.59 (15) |

0.85 (22) |

0.57 (14) |

0.41 (10) |

6.36 (160.8) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.2 (0.51) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.7 (1.78) |

| Source: http://www.wrcc.dri.edu/cgi-bin/cliMAIN.pl?az9114 | |||||||||||||

Geology

Glen Canyon was carved by differential erosion from the Colorado River over an estimated 5 million years. The Colorado Plateau, through which the canyon cuts, arose some 11 million years ago. Within that plateau lie layers of rock from over 300 million years ago to the relatively recent volcanic activity. Pennsylvanian and Permian formations can be seen in Cataract Canyon and San Juan Canyon. The Moenkopi Formation, which dates from 230 million years ago (Triassic Period), and the Chinle Formation are found at Lees Ferry and the Rincon. Both formations are the result of the ancient inland sea that covered the area. Once the sea drained, windblown sand invaded the area, creating what is known as Wingate Sandstone.

The more recent (Jurassic Period) formations include Kayenta Sandstone, which produces the trademark blue-black "desert varnish" that streaks down many walls of the canyons. Above this is Navajo Sandstone. Many of the arches, including Rainbow Bridge, lie at this transition point. This period also includes light yellow Entrada Sandstone, and the dark brown, almost purple Carmel Formation. These latter two can be seen on the tops of mesas around Wahweap, and the crown of Castle Rock and Tower Butte. Above these layers lie the sandstone, conglomerate and shale of the Straight Cliffs Formation that underlies the Kaiparowits Plateau and San Rafael Swell to the north of the lake.

The confluences of the Escalante, Dirty Devil and San Juan rivers with the Colorado lie within Lake Powell. The slower flow of the San Juan river has produced goosenecks where 5 miles (8.0 km) of river are contained within 1-mile (1.6 km) on a straight line.

Landmarks and features

The lake's main body stretches up Glen Canyon, but has also filled many (over 90) side canyons. The lake also stretches up the Escalante River and San Juan River where they merge into the main Colorado River. This provides access to many natural geographic points of interest as well as some remnants of the Anasazi culture.

- Glen Canyon Dam, the dam that keeps Lake Powell the way it is today. (Arizona)

- Rainbow Bridge, one of the world's largest natural bridges. (Utah)

- Hite Crossing Bridge, the only bridge spanning Lake Powell. Although the bridge informally marks the upstream limit of the lake, when the lake is at its normal high water elevation, backwater can stretch up to 30 miles (48 km) upstream into Cataract Canyon.

- Defiance House ruin (Anasazi)

- Castle Rock

- Cathedral in the Desert

- San Juan goosenecks

- Gregory Butte

- Gunsight Butte

- Alstrom Point

- Kaiparowits Plateau

- Hole-in-the-Rock crossing

- the Rincon

- Three-Roof Ruin

- Padre Bay

- Waterpocket Fold

- Antelope Island lies mostly in Arizona just north of Page in the southwest part of Lake Powell.

Development

.jpg.webp)

Access to the lake is limited to developed marinas because most of the lake is surrounded by steep sandstone walls:

- Lee's Ferry

- Page and Wahweap Marina

- Antelope Point Marina

- Halls Crossing, Utah Marina

- Bullfrog Marina

- Hite Marina

The following marinas are accessible only by boat:

- Dangling Rope Marina

- Rainbow Bridge National Monument

- Escalante Subdistrict

Glen Canyon National Recreation Area draws more than two million visitors annually. Recreational activities include boating, fishing, waterskiing, jet-skiing, and hiking. Prepared campgrounds can be found at each marina, but many visitors choose to rent a houseboat or bring their own camping equipment, find a secluded spot somewhere in the canyons, and make their own camp (there are no restrictions on where visitors can stay).

The Castle Rock Cut is one of the most important navigational channels in the lake; it was blasted as early as the 1970s to allow boaters to bypass the winding canyons between the Glen Canyon Dam and reaches of Lake Powell further upstream – saving, on average, one hour of travel time. The cut has been deepened several times since then, to allow the use of the channel during droughts.[14] During the protracted 21st century drought, however, the lake has dropped so quickly on several occasions that the cut dried up during the summer tourist season, most recently in 2013. Continued deepening of the Castle Rock cut has been criticized for its high cost, but boaters and the National Park Service argue that it improves safety, saves millions of dollars in fuel, and improves emergency response time.[15]

Currently most Marinas on the lake don't have Automatic Identification System monitoring stations that transmit boat positions to the AIS websites for the boating community. A substantial number of vessels on the lake do not have AIS transponders as there currently are no mandatory requirements for AIS usage for this body of water. Extra precautions must be taken with respect to boating safety, as the fractal nature of the lake's hydrologic surface area can allow vessels with limited charting equipment to become easily lost.

The burying of human (and pet) waste in Glen Canyon National Recreation Area is prohibited. Anyone who camps farther than a quarter of a mile from a marina must bring a portable toilet. Pet waste must also be packed out.

The southwestern end of Lake Powell in Arizona can be accessed via U.S. Route 89 and State Route 98. State Route 95 and State Route 276 lead to the northeastern end of the lake in Utah.

Fish species

Some of these fish species are on the US Endangered Species List. Currently most native species on the Colorado River Basin are subject to ongoing restoration efforts of some kind.

Bass

Carp, pike and others

- Crappie

- Sunfish

- Channel catfish

- Northern pike

- Walleye

- Common carp

- Razorback sucker

- Brown trout

- Bonytail chub

- Gizzard shad

Invasive species

Zebra and quagga mussels first appeared in the United States in the 1980s.[16]

The mussels were initially brought to the United States through the ballast water of ships entering the Great Lakes. These aquatic invaders soon spread to many bodies of water in the Eastern United States and have even made their way to the western United States. In January 2008,[17][18] Zebra mussels have been detected in several reservoirs along the Colorado River system such as Lakes Mead, Mojave, and Havasu.

By the early 2000s Arizona, California, Nebraska, Kansas, Colorado, Nevada and Utah have all confirmed the presence of larval zebra mussels in lakes and reservoirs.

Zebra and quagga mussels can be destructive to an ecosystem due to competition for resources with native species. The filtration of zooplankton by the mussels can negatively impact the feeding for some species of fish. Zebra and quagga mussels can attach to hard surfaces and build layers on underwater structures. The mussels are known to clog pipes including those in hydroelectric power systems, thus becoming a costly and time-consuming problem for water managers in the West.

Control policies have recently been introduced to alleviate the hydroelectric problems as well as ecological problems faced by Western infestation. Beginning in 1999 Lake Powell began to visually monitor for the mussels.

In 2001 hot water boat decontamination sites were established at Wahweap, Bullfrog, and Halls Crossing marinas. In January 2007, zebra mussels were detected in Lake Mead and new action plans were announced to prevent the spread of mussels to Lake Powell. In August 2007, preliminary testing was positive for zebra or quagga larvae in Lake Powell. These tests were deemed false positives, but adult quagga mussels were found in 2013.

In August 2010, Lake Powell was declared mussel free. Lake Powell introduced a mandatory boat inspection for each watercraft entering the reservoir beginning in June 2009. Effective June 29, 2009, every vessel entering Lake Powell must have a mussel certificate, although boat owners were allowed to self-certify. These measures were intended to help prevent vessels from transporting Zebra mussels into Lake Powell.

Despite these measures, quagga mussel DNA was detected in 2012 and live mussels were found at a number of sites including the Wahweap Marina in Spring and Summer 2013. In June 2013 the NPS was attempting a diver-based eradication program to find and remove mussels before the lake became infested.

References

- "Lake Powell Water Database". lakepowell.water-data.com. 2013. Archived from the original on 17 March 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- Martin, Russell (1989). A Story that Stands Like a Dam: Glen Canyon and the Struggle for the Soul of the West. New York: Henry Holt & Company. ISBN 0-8050-0822-5.

- McPhee, John (1971). Encounters with the Archdruid. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-14822-8.

- Grace, S. "Dam Nation" 2012, PP 114.

- "Upper Colorado Region Water Resources Group : Lake Powell : Water Operations Data: Elevation, Content, Inflow & Release for last 40 Days". United States Bureau of Reclamation. 2013. Archived from the original on 17 March 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- "Upper Colorado Region Water Operations: Current Status: Lake Powell". United States Bureau of Reclamation. 2013. Archived from the original on 10 March 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- "Lake Levels/River Flow". Arizona Game and Fish Department. 2013. Archived from the original on 16 July 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- "Water Database". Lakepowell.water-data.com. Archived from the original on 2016-09-24. Retrieved 2016-07-22.

- "Water Database". Lakepowell.water-data.com. Archived from the original on 2016-09-24. Retrieved 2016-07-22.

- "Water Database". Lakepowell.water-data.com. Archived from the original on 2016-09-24. Retrieved 2016-07-22.

- "Water Database". Lakepowell.water-data.com. Archived from the original on 2016-09-24. Retrieved 2016-07-22.

- "Water Database". Lakepowell.water-data.com. Archived from the original on 2016-09-24. Retrieved 2016-07-22.

- "Glen Canyon Dam: Water Operations | UC Region | Bureau of Reclamation". www.usbr.gov. Archived from the original on 22 September 2020. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- Correspondent, Todd Glasenapp Sun. "Deeper Lake Powell shortcut completed". azdailysun.com. Archived from the original on 2015-07-30.

- "Castle Rock Cut To Be Deepened Again at Glen Canyon National Recreation Area - National Parks Traveler". www.nationalparkstraveler.com. Archived from the original on 2016-08-29.

- "Zebra Mussel Watch". Friends of Lake Powell. 2009. Archived from the original on 8 May 2013. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- "Zebra Mussels detected in Lake Pueblo State Park". Colorado Parks and Wildlife. 17 January 2008. Archived from the original on 15 July 2012. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

- "Zebra mussels detected at Lake Pueblo State Park". The Denver Post. 17 January 2008. Archived from the original on 3 May 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2013.

Bibliography

- Martin, Russell, A Story That Stands Like a Dam: Glen Canyon and the Struggle for the Soul of the West, Henry Holt & Co, 1989

- McPhee, John, "Encounters with the Archdruid," Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1971

- Nichols, Tad, Glen Canyon: Images of a Lost World, Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press, 2000

- Abbey, Edward, Desert Solitaire, Ballantine Books, 1985

- Glick, Daniel (April 2006). "A Dry Red Season: Uncovering the Glory of Glen Canyon,". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 2007-08-07. Retrieved 2007-10-21.

- Farmer, Jared, Glen Canyon Dammed: Inventing Lake Powell and the Canyon Country, Tucson: The University of Arizona Press, 1999

- Stiles, Jim, The Brief but Wonderful Return of Cathedral in the Desert, Salt Lake Tribune, June 7, 2005

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lake Powell. |

- Water Level in Lake Powell, slide show of ten years of images from NASA’s Landsat 5 satellite, showing dramatic fluctuations in water levels in Lake Powell.

- Lake Powell Water Database - water level, basin snowpack, and other statistics

- Lake Powell Resorts and Marinas

- Friends of Lake Powell - organization opposed to decommissioning Glen Canyon Dam

- Glen Canyon National Recreation Area (National Park Service)