Legislative assemblies of the Roman Republic

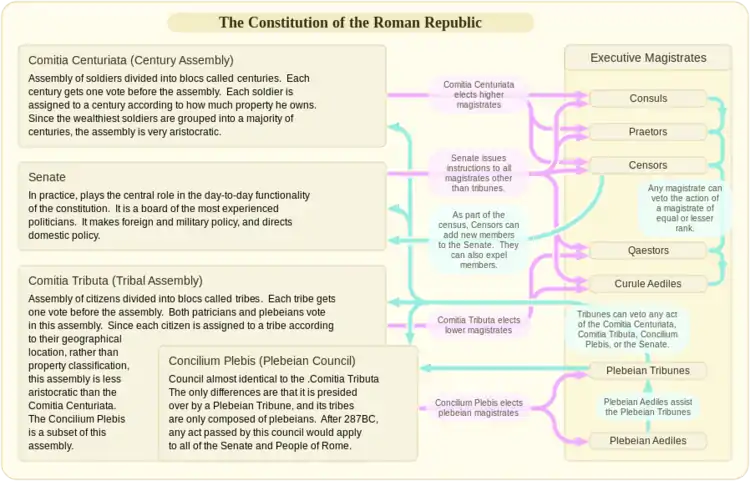

The legislative assemblies of the Roman Republic were political institutions in the ancient Roman Republic. According to the contemporary historian Polybius, it was the people (and thus the assemblies) who had the final say regarding the election of magistrates, the enactment of Roman laws, the carrying out of capital punishment, the declaration of war and peace, and the creation (or dissolution) of alliances. Under the Constitution of the Roman Republic, the people (and thus the assemblies) held the ultimate source of sovereignty.

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of ancient Rome |

| Periods |

|

| Roman Constitution |

| Precedent and law |

|

|

| Assemblies |

| Ordinary magistrates |

| Extraordinary magistrates |

| Titles and honours |

Since the Romans used a form of direct democracy, citizens, and not elected representatives, voted before each assembly. As such, the citizen-electors had no power, other than to cast a vote. Each assembly was presided over by a single Roman Magistrate, and as such, it was the presiding magistrate who made all decisions on matters of procedure and legality. Ultimately, the presiding magistrate's power over the assembly was nearly absolute. The only check on that power came in the form of vetoes handed down by other magistrates.

In the Roman system of direct democracy, two primary types of gatherings were used to vote on legislative, electoral, and judicial matters. The first was the Assembly (comitia), which was a gathering that was deemed to represent the entire Roman people, even if it did not contain all of the Roman citizens or, like the comitia curiata, excluded a particular class of Roman citizens (the plebs). The second was the Council (concilium), which was a gathering of citizens of a specific class. In contrast, the Convention was an unofficial forum for communication. Conventions were simply forums where Romans met for specific unofficial purposes, such as, for example, to hear a political speech. Voters always assembled first into Conventions to hear debates and conduct other business before voting, and then into Assemblies or Councils to actually vote.

Assembly procedure

There were no set dates to hold assemblies, but notice had to be given beforehand if the assembly was to be considered formal. Elections had to be announced 17 days before the election took place. Likewise, 17 days had to pass between the proposal of legislation and its enactment by an assembly.[1]

In addition to the presiding magistrate, several additional magistrates were often present to act as assistants.[2] There were also religious officials known as augurs either in attendance or on-call, who would be available to help interpret any signs from the gods (omens).[2] On several known occasions, presiding magistrates used the claim of unfavorable omens as an excuse to suspend a session that was not going the way they wanted.[3] Any decision made by a presiding magistrate could be vetoed by a magistrate known as a Plebeian Tribune. In addition, decisions made by presiding magistrates could also be vetoed by higher-ranking magistrates.

On the day of the vote, the electors first assembled into their conventions for debate and campaigning.[4] In the Conventions, the electors were not sorted into their respective units (curia, centuries or tribes). Speeches from private citizens were only heard if the issue to be voted upon was a legislative or judicial matter.[5] If the purpose of the ultimate vote was for an election, no speeches from private citizens were heard, and instead, the candidates for office used the Convention to campaign.[6] During the Convention, the bill to be voted upon was read to the assembly by an officer known as a "Herald". Then, if the assembly was composed of Tribes, the order of the vote had to be determined. A Plebeian Tribune could use his veto against pending legislation until the point when the order of the vote was determined.[7]

The electors were then told to break up the Convention and assemble into the formal Assembly or Council. The electors voted by placing a pebble or written ballot into an appropriate jar.[4][8] The baskets that held the votes were watched by specific officers, who then counted the ballots, and reported the results to the presiding magistrate. The majority of votes in any Curia, Tribe, or Century decided how that Curia, Tribe, or Century voted. Each Curia, Tribe, or Century received one vote, regardless of how many electors each Tribe or Century held. Once a majority of Curiae, Tribes, or Centuries voted in the same way on a given measure, the voting ended, and the matter was decided.[9]

If a law was passed in violation of proper procedures (such as failing to wait 17 days before voting on a law), the Senate could declare the law nonbinding.[10]

Assembly of the Curiae

The Curiate Assembly (comitia curiata) was the principal assembly during the first two decades of the Roman Republic. The Curiate Assembly was organized as an Assembly, and not as a Council even though only patricians were members. During these first decades, the People of Rome were organized into thirty units called Curiae.[11][12] The Curiae were ethnic in nature, and thus were organized on the basis of the early Roman family, or, more specifically, on the basis of the thirty original Patrician (aristocratic) clans.[13] The Curiae assembled into the Curiate Assembly, for legislative, electoral, and judicial purposes. The Curiate Assembly passed laws, elected Consuls (the only elected magistrates at the time),[14] and tried judicial cases. Consuls always presided over the assembly.[15]

Shortly after the founding of the republic, most of the powers of the Curiate Assembly were transferred to the Centuriate Assembly and the Tribal Assembly.[11] While it then fell into disuse, it did retain some theoretical powers, most importantly, the power to ratify elections of the top-ranking Roman Magistrates (Consuls and Praetors) by passing the statute that gave them their legal command authority, the lex curiata de imperio. In practice, however, they actually received this authority from the Centuriate Assembly (which formally elected them), and as such, this functioned as nothing more than a reminder of Rome's regal heritage.[12] Other acts that the Curiate Assembly voted on were mostly symbolic and usually in the affirmative.[12] At one point, possibly as early as 218 BC, the Curiate Assembly's thirty Curia were abolished, and replaced with thirty lictors, one from each of the original Patrician clans.[12] Since the Curia had always been organized on the basis of the Roman family,[13] the Curiate Assembly actually retained jurisdiction over clan matters even after the fall of the Roman Republic in 27 BC.[14] Under the presidency of the Pontifex Maximus,[11] it witnessed wills and ratified adoptions,[11] inaugurated certain priests, and transferred citizens from Patrician class to Plebeian class (or vice versa). In 44 BC, for example, it ratified the will of Julius Caesar, and with it Caesar's adoption of his nephew Gaius Octavian (the future Roman emperor Augustus) as his son and heir.[12] However, this might not have been the comitia curiata but instead the comitia calata.

Assembly of the Centuries

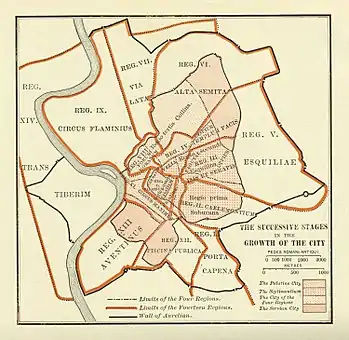

The Centuriate Assembly (comitia centuriata or "Army Assembly") of the Roman Republic was originally the democratic assembly of the Roman soldiers. The Centuriate Assembly organized the Roman citizens into classes, which were defined by a means test and were economic in nature.[16] The Roman army was divided into units called "Centuries", and these gathered into the Centuriate Assembly for legislative, electoral, and judicial purposes. However, since the number of centuries in each class was fixed, centuries could contain far more than 100 men. Only this assembly could declare war or elect the highest-ranking Roman Magistrates: Consuls, Praetors and Censors.[17] The Centuriate Assembly could also pass a statute that granted constitutional command authority to Consuls and Praetors, and Censorial powers to Censors.[17] In addition, the Centuriate Assembly served as the highest court of appeal in certain judicial cases, and ratified the results of the Census.[12] While the voters in this assembly wore white undecorated togas and were unarmed, while taking part in the Assembly they were classified as soldiers, and as such they could not meet inside of the physical boundary of the city of Rome.[17] The president of the Centuriate Assembly was usually a Consul (although sometimes a Praetor). Only Consuls (the highest-ranking of all Roman Magistrates) could preside over the Centuriate Assembly during elections because the higher-ranking Consuls were always elected together with the lower-ranking Praetors. Once every five years, after the new Consuls for the year took office, they presided over the Centuriate Assembly as it elected the two Censors.

The Centuriate Assembly was supposedly founded by the legendary Roman King Servius Tullius, less than a century before the founding of the Roman Republic in 509 BC. As such, the original design of the Centuriate Assembly was known as the "Servian organization". Under this organization, the assembly was supposedly designed to mirror the Roman army during the time of the Roman Kingdom. Soldiers in the Roman army were classified on the basis of the amount of property that they owned, and as such, soldiers with more property had more influence than soldiers with less property. The 193 Centuries in the assembly under the Servian Organization were each divided into one of three different grades: the officer class, the enlisted class, and a class of unarmed adjuncts.[18] The officer class was grouped into eighteen Centuries.[18] The enlisted class was grouped into five separate property classes, for a total of 170 Centuries.[19] The unarmed soldiers were divided into the final five Centuries.[20] Of five enlisted classes, the wealthiest controlled 80 of the votes.[21] During a vote, all of the Centuries of one class had to vote before the Centuries of the next lower class could vote.[22] The first candidate to reach a majority of 97 votes was victorious. When a measure or candidate received 97 votes, a majority of the centuries, the voting ended, and as such, many lower ranking Centuries rarely if ever had a chance to actually vote. Combined the 18 equites and the 80 centuries of the first property class had one more century than needed, and a unanimous vote from the elite would thus elect a candidate.[23]

In 241 BC, the assembly was reorganized, though the exact details are uncertain. Some sources have a new total of 373 Centuries,[24] but Cicero still writes of 193 centuries in his era, and most scholars still use that number[25] It known that the first property class was reduced form 80 to 70 centuries, and the order of voting was changed so that the first class would go first, and be followed by the equites.[26]

The lowest ranking Century in the Centuriate Assembly was the fifth Century (called the proletarii) of the unarmed adjunct class. This Century was the only Century composed of soldiers who had no property, and since it was always the last Century to vote, it never had any real influence on elections. In 107 BC, in response to high unemployment and a severe manpower shortage in the army, the general and Consul Gaius Marius reformed the organization of the army, and allowed individuals with no property to enlist. As a consequence of these reforms, this fifth unarmed Century came to encompass almost the entire Roman army.[22] This mass disenfranchisement of most of the soldiers in the army played an important role in the chaos that led to the fall of the Roman Republic in 27 BC.[22]

During his dictatorship from 82 BC until 80 BC, Lucius Cornelius Sulla restored the old Servian Organization to this assembly. Sulla died in 78 BC, and in 70 BC, the Consuls Pompey Magnus and Marcus Licinius Crassus repealed Sulla's constitutional reforms, including his restoration of the Servian Organization to this assembly. Thus, they restored the newer organization that had originated in 241 BC. The organization of the Centuriate Assembly was not changed again until its powers were all transferred to the Roman Senate by the first Roman Emperor, Augustus, after the fall of the Roman Republic in 27 BC.[27]

Assembly of the Tribes

The Tribal Assembly (comitia populi tributa) of the Roman Republic was the democratic assembly of Roman citizens. The Tribal Assembly was organized as an Assembly, and not as a Council. During the years of the Roman Republic, citizens were organized on the basis of thirty-five Tribes which included patricians and plebeians. The Tribes gathered into the Tribal Assembly for legislative, electoral, and judicial purposes. The president of the Tribal Assembly was usually either a Consul (the highest ranking Roman Magistrate) or a Praetor (the second-highest ranking Roman Magistrate). The Tribal Assembly elected three different magistrates: Quaestors, Curule Aediles, and Military Tribunes.[28] The Tribal Assembly also had the power to try judicial cases.[29]

The thirty-five Tribes were not ethnic or kinship groups, but rather a generic division into which Roman citizens were distributed. When the Tribes were created the divisions were geographical, similar to modern Parliamentary constituencies. However, since one joined the same Tribe that one's father belonged to, the geographical distinctions were eventually lost.[30] The order that the 35 Tribes voted in was selected randomly by lot. The order was not chosen at once, and after each Tribe had voted, a lot was used to determine which Tribe should vote next.[31] The first Tribe selected was usually the most important Tribe, because it often decided the matter. It was believed that the order of the lot was chosen by the Gods, and thus, that the position held by the early voting Tribes was the position of the Gods.[32] Once a majority of Tribes had voted the same way, voting ended.[9]

Plebeian Council

The Plebeian Council (concilium plebis) was the principal popular gathering of the Roman Republic. As the name suggests, the Plebeian Council was organized as a Council, and not as an Assembly. It functioned as a gathering through which the Plebeians (commoners) could pass laws, elect magistrates, and try judicial cases. This council had no political power until the offices of Plebeian Tribune and Plebeian Aedile were created in 494 BC, due to the Plebeian Secession that year.[29]

According to legend, the Roman King Servius Tullius enacted a series of constitutional reforms in the 6th century BC. One of these reforms resulted in the creation of a new organizational unit with which to divide citizens. This unit, the Tribe, was based on geography rather than family, and was created to assist in future reorganizations of the army.[20] In 471 BC,[33] a law was passed which allowed the Plebeians to begin organizing by Tribe. Before this point, they had organized on the basis of the Curia.[29] The only difference between the Plebeian Council after 471 BC and the ordinary Tribal Assembly (which also organized on the basis of the Tribes) was that the Tribes of the Plebeian Council only included Plebeians, whereas the Tribes of the Tribal Assembly included both Plebeians and Patricians.[29]

The Plebeian Council elected two 'Plebeian Magistrates', the Plebeian Tribunes and the Plebeian Aediles.[33] Usually the Plebeian Tribune presided over the assembly, although the Plebeian Aedile sometimes did as well. Originally, statutes passed by the Plebeian Council ("Plebiscites") only applied to Plebeians.[34] However, in 449 BC, a statute of an Assembly was passed which gave Plebiscites the full force of law over all Romans (Plebeians and Patricians).[35] It was not until 287 BC, however, that the last mechanism which allowed the Roman Senate to veto acts of the Plebeian Council was revoked. After this point, almost all domestic legislation came out of the Plebeian Council.

See also

Notes

- Lintott, 44

- Taylor, 63

- Taylor, 96

- Taylor, 2

- Lintott, 45

- Taylor, 16

- Lintott, 46

- Lintott, 46–47

- Taylor, 40

- Lintott, 62

- Byrd, 33

- Taylor, 3–4

- Abbott, 250

- Abbott, 253

- Holland, 5

- McCullough, 943

- Abbott, 257

- Taylor, 85

- Taylor, 87

- Abbott, 21

- E. S. Staveley. Greek and Roman Voting and Elections. Cornell University Press, 1972, p. 126.

- Taylor, 86

- Rachel Feig Vishnia. Roman Elections in the Age of Cicero: Society, Government, and Voting. Routledge, Mar 12, 2012, p. 113.

- Abbott, 75

- E. S. Staveley. Greek and Roman Voting and Elections. Cornell University Press, 1972, p. 127.

- Rachel Feig Vishnia. Roman Elections in the Age of Cicero: Society, Government, and Voting. Routledge, Mar 12, 2012, p. 123.

- Abbott, 107

- Taylor, 7

- Abbott, 261

- Lintott, 51

- Taylor, 77

- Taylor, 76

- Abbott, 196

- Byrd, 31

- Abbott, 51

References

- Abbott, Frank Frost (1901). A History and Description of Roman Political Institutions. Elibron Classics. ISBN 0-543-92749-0.

- Byrd, Robert (1995). The Senate of the Roman Republic. US Government Printing Office Senate Document 103–23.

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius (1841). The Political Works of Marcus Tullius Cicero: Comprising his Treatise on the Commonwealth; and his Treatise on the Laws. Vol. 1 (Translated from the original, with Dissertations and Notes in Two Volumes By Francis Barham, Esq ed.). London: Edmund Spettigue.

- Holland, Tom (2005). Rubicon: The Last Years of the Roman Republic. Random House Books. ISBN 1-4000-7897-0.

- Lintott, Andrew (1999). The Constitution of the Roman Republic. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-926108-3.

- Polybius (1823). The General History of Polybius: Translated from the Greek. Vol. 2 (Fifth ed.). Oxford: Printed by W. Baxter.

- Taylor, Lily Ross (1966). Roman Voting Assemblies: From the Hannibalic War to the Dictatorship of Caesar. The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08125-X.

- McCullough, Colleen (1990). The First Man in Rome. Avon Books. ISBN 0-380-71081-1.

Further reading

- Cambridge Ancient History, Volumes 9–13.

- Cameron, A. The Later Roman Empire, (Fontana Press, 1993).

- Crawford, M. The Roman Republic, (Fontana Press, 1978).

- Gruen, E. S. "The Last Generation of the Roman Republic" (U California Press, 1974)

- Ihne, Wilhelm. Researches Into the History of the Roman Constitution. William Pickering. 1853.

- Johnston, Harold Whetstone. Orations and Letters of Cicero: With Historical Introduction, An Outline of the Roman Constitution, Notes, Vocabulary and Index. Scott, Foresman and Company. 1891.

- Millar, F. The Emperor in the Roman World, (Duckworth, 1977, 1992).

- Mommsen, Theodor. Roman Constitutional Law. 1871-1888

- Polybius. The Histories

- Tighe, Ambrose. The Development of the Roman Constitution. D. Apple & Co. 1886.

- Von Fritz, Kurt. The Theory of the Mixed Constitution in Antiquity. Columbia University Press, New York. 1975.

External links

- Cicero's De Re Publica, Book Two

- Rome at the End of the Punic Wars: An Analysis of the Roman Government; by Polybius

- Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and their Decline, by Montesquieu

- The Roman Constitution to the Time of Cicero

- What a Terrorist Incident in Ancient Rome Can Teach Us