Adoption in ancient Rome

Adoption in Ancient Rome was practiced and performed by the upper classes; a large number of adoptions were performed by the Senatorial class.[1] Succession and family legacy were very important; therefore Romans needed ways of passing down their fortune and name when unable to produce a male heir. Adoption was one of the few ways to guarantee succession, so it became a norm to adopt young males into the homes of high ranking families. Due to the Roman inheritance laws (Falcidia Lex),[2] women had very little rights or the ability to inherit fortunes. This made them less valuable for adoption. However, women were still adopted and it was more common for them to be wed to an influential family.

Causes

One of the benefits of a male heir was the ability to create ties among other high-ranking families through marriage. Senators throughout Rome had the responsibility of producing sons who could inherit their family’s title and estate. Childbirth was very unpredictable during these times and there was no way of knowing gender before birth. This caused many children to be lost in the years directly after and it was hard for the senators to control the situation. With the cost of children being high and average families having very few children, this posed a challenge for the senators. Without a male heir, their title and estate could be forfeited. This was the leading cause for adoption in ancient Rome. It is important to note that adoption in ancient Rome was used for a number of reasons and not exclusively by senators. The use by senators guaranteed them a son; this gave senators the freedom to produce children more freely knowing a male heir could always be adopted if unable to produce one naturally. This also created new benefits for female babies enabling them to be given away for adoption into higher ranked families. With the reduced risk of succession issues this created opportunities for males children to marry into other high-ranking families to create powerful ties among the upper class. In the case of the lower classes, raising a large family was quite challenging. Due to the cost, this allowed them to put their children up for adoption. It would benefit both the families and the child. One famous example of this is when Lucius Aemilius put his own two sons up for adoption.[1]

Practice

In Rome, the person in charge of adoption was the male head of the household called the paterfamilias. Adoption would result in an adoption of power for the adopted child as the status of the adopting family was immediately transferred to the child. This was almost always an increase in power due to the high cost of adoption. Publius Clodius Pulcher famously used this loophole for political power in his attempt to gain control over the plebs.[3] During the Roman Republic, the same laws stood in place with only one difference; the requirement of the Senate's approval.

The actual adoption was often operated like a business contract between the two families. The adopted child took the family name as his own. Along with this, the child kept his/her original name through the form of cognomen or essentially a nickname. The adopted child also maintained previous family connections and often leveraged this politically. Due to the power disparity that normally existed between the families involved in adoption, a fee was often given to the lower family to help with replacing (in most cases) the first-born son. Another case similar to adoption was the fostering of children; this effectively took place when a paterfamilias transferred his power to another man to be left in their care.[4]

Former slaves who were freed by their masters could be allowed to adopt his children to legitimize them.[5]

Adoption of women

Throughout Roman history many adoptions took place but very few accounts of female adoption were recorded and preserved throughout history. With men holding the spotlight in history books and articles, it is possible that adoption of girls was more popular. However, because most of the famous adoptions were male children, female adoptions could have been wrongfully accounted. Additionally, because the legal impacts of women in ancient Rome were so minimal, it is possible that adoptions could have been more informal and therefore less accounted for in history. One of the most well known was Livia Augusta who gained this name after her adoption into the Julian family. Known mainly as the wife of Augustus. Livia played a key role during this time in the Roman Empire both as a political symbol and a role model for Roman households. Livia earned herself an honorable place among history as a great mother however some of the rumors related to potential heirs have survived throughout history.[6]

Imperial succession

Many of Rome’s famous emperors came to power through adoption, either because their predecessors had no natural sons or simply to ensure a smooth transition for the most capable candidate.

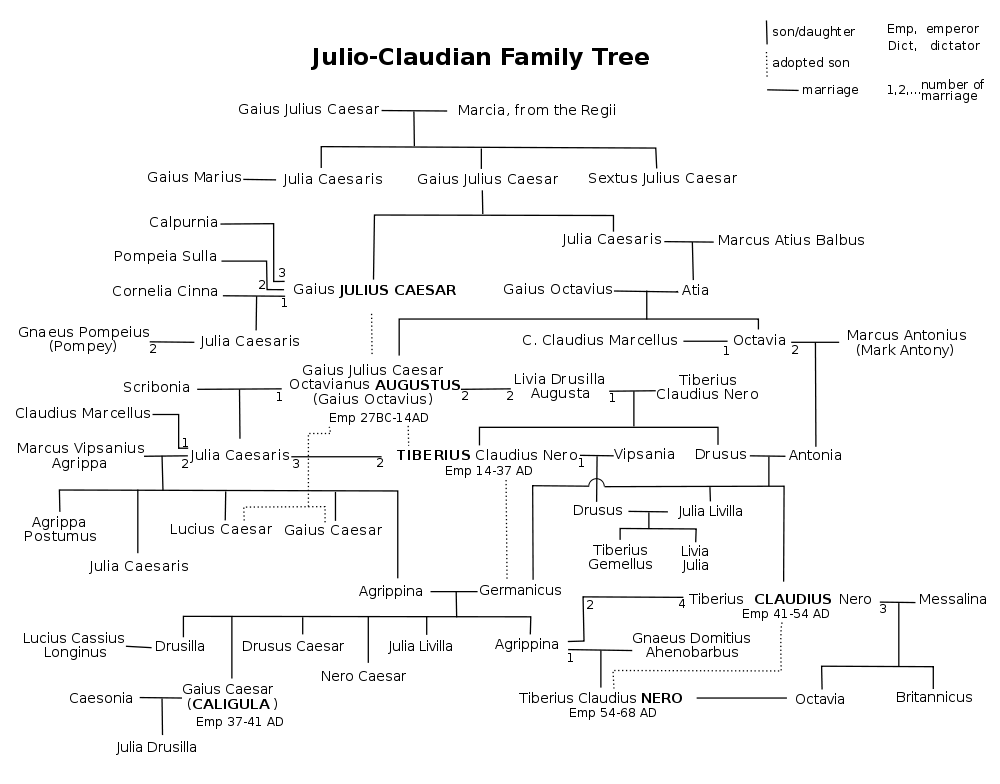

The Julio-Claudian Dynasty

The first emperor, Augustus, owed much of his success to having been adopted into the gens Julia in the will of his great uncle, Julius Caesar. However, the office of emperor did not exist at that time; Octavian inherited Caesar's money, name and auctoritas but not the office of dictator.

As Augustus's central role in the principate solidified, it became increasingly important for him to designate an heir. He first adopted his daughter Julia's three sons by Marcus Agrippa, renaming them Gaius Caesar, Lucius Caesar and Marcus Julius Caesar Agrippa Postumus. After the former two died young and the latter was exiled, Augustus adopted his stepson Tiberius Claudius Nero on condition that he adopt his own nephew, Germanicus (who was also Augustus's great nephew by blood). Tiberius succeeded Augustus and on Tiberius's death Germanicus's son Caligula became emperor.

Claudius adopted his stepson Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus, who changed his name to Nero Claudius Caesar and succeeded Claudius as the emperor Nero.

The Adoptive Emperors

The Nerva-Antonine dynasty was also united by a series of adoptions. Nerva adopted the popular military leader Trajan. Trajan in turn took Publius Aelius Hadrianus as his protégé and, although the legitimacy of the process is debatable, Hadrian claimed to have been adopted and took the name Caesar Traianus Hadrianus when he became emperor.

Hadrian adopted Lucius Ceionius Commodus, who changed his name to Lucius Aelius Caesar but predeceased Hadrian. Hadrian then adopted Titus Aurelius Fulvus Boionius Arrius Antoninus, on condition that Antoninus in turn adopt both the natural son of the late Lucius Aelius and a promising young nephew of his wife. They ruled as Antoninus Pius, Lucius Verus and Marcus Aurelius respectively.

Niccolò Machiavelli described them as The Five Good Emperors and attributed their success to having been chosen for the role:

From the study of this history we may also learn how a good government is to be established; for while all the emperors who succeeded to the throne by birth, except Titus, were bad, all were good who succeeded by adoption, as in the case of the five from Nerva to Marcus. But as soon as the empire fell once more to the heirs by birth, its ruin recommenced.[7]

This run of adoptive emperors came to an end when Marcus Aurelius named his biological son, Commodus, as his heir.

One reason why adoption never became the official method of designating a successor was because hereditary rule was against republican principles and the republic had never been abandoned in law, even though the emperors of the Principate behaved as monarchs. The Dominate of Diocletian effectively replaced adoption with Consortium imperii - designating an heir by appointing him partner in imperium.

See also

References

- Weigel, Richard D. (January 1978). "A Note on P. Lepidus". Classical Philology. 73 (1): 42–45. doi:10.1086/366392. ISSN 0009-837X.

- "LacusCurtius • Roman Law — Adoption (Smith's Dictionary, 1875)". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2020-03-10.

- Connerty, Victor (2000). Tatum, W. J. (ed.). "Publius Clodius Pulcher". The Classical Review. 50 (2): 514–516. doi:10.1093/cr/50.2.514. ISSN 0009-840X. JSTOR 3064795.

- "Adoption in the Roman Empire". Life in the Roman Empire. Retrieved 2020-03-10.

- https://books.google.se/books?id=85Gdul_43DEC&pg=PA161&dq=%22claudius%22+%22illegitimate+children%22&hl=sv&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjZ2vHq-vDtAhXD_CoKHUfiC5kQ6AEwB3oECAcQAg#v=onepage&q=%22claudius%22%20%22illegitimate%20children%22&f=false

- Huntsman, Eric D. (2009). "Livia Before Octavian". Ancient Society. 39: 121–169. doi:10.2143/AS.39.0.2042609. ISSN 0066-1619. JSTOR 44079922.

- Machiavelli, Discourses on Livy, Book I, Chapter 10.