Manufacturing in Hong Kong

Manufacturing in Hong Kong consists of mainly light and labour-intensive industries. Manufacturing started in the 19th century after the Taiping Rebellion and continues today, although it has largely been replaced by service industries, particularly those involving finance and real estate.

| Economy of Hong Kong |

|---|

| Identity |

| Resources |

| Companies |

|

| Other Hong Kong topics |

|

|

| Hong Kong Portal |

As an entrepôt, Hong Kong had limited manufacturing development until the Second World War, when the development of manufacturing industries was discontinued due to the Japanese occupation. Manufacturing in the city revived after the War. The 1950s saw the city's transition from an entrepôt to a manufacturing-based economy. The city's manufacturing industry grew rapidly over the next decade. The industries were diversified in different aspects in the 1970s. One of the most notable reasons of diversification was the oil crisis.

Early development

1842 to 1918

After the British acquisition of Hong Kong Island in 1842, manufacturing started to develop. Most factories were limited to small workshops producing hand-made goods. Primitive methods, techniques and facilities were used for production. Productivity was low and manufacturing was not as important as the re-exportation, which was most important at the time.[1]

At the beginning of the colonial era, all factories in the city were owned by the British.[2] The British-owned factories were mainly limited to shipbuilding and rattan furniture.[3] British industrialists did not consider Hong Kong to be favourable for manufacturing because Hong Kong lacked natural resources, and instead focussed on entrepôt trade and such related industries as shipping and banking.[3]

Guangdong officials fled to Hong Kong because of the Taiping Rebellion in the 1850s and 60s, bringing in capital and boosting manufacturing. Such factories were the first Chinese-owned ones to appear in Hong Kong. The first printing company appeared in 1872, followed by many different industries such as sweets,[3][4] clothing and soap-making.[2] By the end of the 19th century, the first mechanised factories emerged, including a match factory and a pulp company.[3][4]

Small metal and electronic goods had emerged in the early 20th century.[2] With the development of commerce, a few large manufacturing firms appeared. Although these firms were few in number, there was large investment into them and most were leaders in their respective industries.[5] After the Chinese Revolution, many Chinese firms relocated to Hong Kong to avoid the constant warfare between warlords.[5] During the First World War, supplies of daily necessities from Europe were cut off. Industries such as towels, cigarettes and biscuits emerged to support the local population, resulting in a rise in the light industries.[2]

1919 to 1950

The 1920s and 30s saw the initial rise of the city's manufacturing. The textile industry became the backbone of Hong Kong's manufacturing sector. Industries such as the firecracker, glass and leather industries also emerged,[6] and there was a shift from hand-made to machine-made products.[5] Nevertheless, Hong Kong's manufacturing sector was still behind most industrialised cities as the source of capital was rather narrow and was largely limited to Guangdong entrepreneurs. There are several factors leading to the rise of manufacturing in the 1920s and 30s, including a decline in European industries,[5] the tax reduction granted by the Ottawa Agreement of 1932, and the relocation of factories from Mainland China to Hong Kong.[2] For example, Cheoy Lee Shipyard, the largest Hong Kong-based shipbuilding company as of 2009, moved from Shanghai to Hong Kong in 1936 because of military conflicts between China and Japan.[7]

Manufacturing in Hong Kong faced many challenges during the early 1930s. After China regained the right to control its tariffs in 1928, the tax imposed on Hong Kong goods rose tremendously, but the Chinese government rejected pleas from Hong Kong industrialists to lower tariffs.[6] The United Kingdom's abolishment of the gold standard destabilised exchange rates. Japan's dumping policy also hit Hong Kong, which did not impose tariffs on exports. The consumption power of Mainland China decreased.[5] The Great Depression further damaged manufacturing in the city and led to the liquidation of over 300 factories.[6] However, a series of favourable events led to another surge in manufacturing in 1935, including a decline in Japanese and Italian goods, the stabilisation of exchange rates, an expansion in mainland markets, and the rise of the Malay Archipelago.[8]

By 1941, there were 1250 factories in Hong Kong with nearly 100,000 employees in manufacturing. The largest industries at the time were shipbuilding, textile manufacturing, torches and plastic shoes. These goods were sold to Mainland China as well as other Southeast Asian countries near the South China Sea. Among these industries, the largest was the shipbuilding industry. The shipyards of Tai Koo, Hung Hom Bay and Cheoy Lee Shipyard were the largest, each employing over 4,000 people.[2]

Manufacturing declined during the Japanese occupation. Like most other industries of the city, they faced a near-total destruction by the Japanese.[1] After the end of the Second World War in 1945, Hong Kong earned much by resuming its role as an entrepôt. From 1945 to 1950, its earnings by re-exportation rose by over half every year.[9] This led to the restoration of the city's economy. During this period, most factories that were shut down during the Japanese occupation period were reopened.[1]

Industrialisation

During the 1950s and 1960s Hong Kong was restructured from being an entrepôt to being an industrial city.[1] This was also the first change in economic structure.

One cause of industrialisation was the Korean War. The United States' embargo on China led to a decline in the entrepôt trade with China, Hong Kong's biggest market at the time. But Hong Kong focused on manufacturing instead.[10] Moreover, as China's products could not be exported, Hong Kong replace these exports.[10] In 1954, the United Nations bought 10 ships from Cheoy Lee Shipyard to assist in the revival of Korea.[11]

Another factor was the Chinese Civil War. After the Second Sino-Japanese War, Chinese businesses bought huge numbers of machines and facilities to restore their pre-war production. When the Civil War broke out, many businesses moved those facilities to Hong Kong warehouses to continue production. Furthermore, industrialists from Tianjin, Shanghai and Guangzhou relocated to Hong Kong because of the Civil War. They brought skilled labour, technology and capital to Hong Kong.[12] Many Mainlanders also fled to Hong Kong, adding to the city's workforce. Altogether, some US$100 million were brought to Hong Kong because of the Civil War. After the war, the facilities and equipment stayed in Hong Kong, leading to a rise in Hong Kong's manufacturing.[10] From 1946 to 1948, the number of factories increased by 1211 and 81,700 workers were employed in manufacturing.[1]

The economic restructuring of more developed countries was another factor. After the Second World War, Western countries started to upgrade their products and technology, leaving labour-intensive industries to the less developed countries. This encouraged overseas investment and allowed developed technology to be imported to Hong Kong, boosting manufacturing there.[10]

1952 to 1962

From 1952 to 1954, the rate of growth was relatively low. The number of factories increased from 1902 to 2001, while the number of workers employed in manufacturing rose from 85,300 to 98,200. Nevertheless, the total value of domestic exports dropped from HK$29,000,000 to HK$24,170,000. This was because manufacturers focused on building factories and altering their products rather than increasing productivity.[13]

From 1955 to 1962, the rate of growth was faster. The number of factories increased 80%, while the number of factory workers increased 160%. However, the value of exports decreased from 1958 to 1959. In 1959, for the first time, the value of re-exports exceeded exports. By 1962, the value of re-exports had shrunk again to a third of exports.[13]

During this period, textile manufacturing and clothing industries took the lead. The Kwun Tong Industrial Estate was the first industrial estate in Hong Kong. By the early 1960s, Hong Kong's textile manufacturing was the most successful in Asia.[14]

The textile industry in particular flourished at the time. Chinese textile manufacturers set up many factories in Tsuen Wan.[1] Some of them had dyeing factories and their own docks.[14]

1963 to 1970

Hong Kong industrialised rapidly from 1963 to 1970. Existing industries continued to prosper, while new industries emerged and thrived as well. The number of factories increased 67% while the number of workers increased 15%. The number of factories and workers in 1970 were 16,507 and 549,000 respectively. The latter took up over 40% of the city's employment structure. The value of exports continued to rise, and in just two years, rose by 172% to HK$12,347,000,000. Hong Kong ceased to be reliant on re-exportation.[13]

One of the new industries that took the lead was electronics, which started in the 1960s. Another industry was the watch industry.[15] Hong Kong manufacturers mainly made cheap watches and watch parts in the 1960s.[16] Likewise, the manufacture of toys also started to succeed during this period.[13]

The textile industry, an existing industry, continued to prosper from 1963 to 1970. Another existing industry, the clothing industry, expanded greatly with higher technology. Clothing was exported, including to Europe and North America. The Tai Koo and Hung Hom Bay shipyards were turned into housing estates, while Cheoy Lee Shipyard remained and became the first factory to produce boats with fibreglass.[17]

Hong Kong's industrial areas expanded along Victoria Harbour during this period. Prior to the 1960s, most industrial areas were built along both sides of Victoria Harbour. Such areas were turned into commercial or residential areas.[18]

Diversification

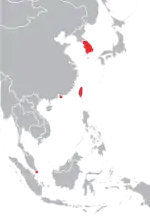

After the industrialisation of Hong Kong, it faced two major crises in the 1970s, namely the oil crisis and the rise of other industrial states and cities with similar economic structures, such as Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Brazil and Mexico. The first three, along with Hong Kong, are known collectively as the Four Asian Tigers. Before this, the city's economy had faced little competition since Hong Kong's industrial development was earlier than the industrial development of most others.[19]

To rescue the city's manufacturing, several measures were taken. First, relatively new industries such as toy, electronics and watches, were developed quickly so that the clothing and textile industries no longer dominated the market.[19] This was also due to the fact that Western countries imposed severe restrictions on textile imports, while toys, electronics and watches enjoyed lower tariffs. In 1972, Hong Kong replaced Japan as the largest exporter of toys.[20] Swiss watch companies also moved some of their factories to Hong Kong.[16]

In addition, the quality of products improved. The large number of cheap products were replaced by a smaller number of higher quality and value-added products. Quality and technology of products were also increased as competition increased. The variety of products widened. Hong Kong companies also used flexible ways of producing goods. Faced with the severe restrictions in foreign countries, companies made use of the diversity of their products so that other products could be exported when one kind was restricted. The high value-added jewellery industry, emerged in the 1970s.[20]

Places of origin of raw materials became more diversified. For example, Hong Kong bought raw material from Taiwan, Singapore and Korea to reduce reliance on Japan. Imports of raw materials from European and American countries decreased, while imports of raw materials from Asia increased.[21]

Exportation was no longer limited to large countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom and West Germany. Much effort was put to selling products to smaller countries, although large countries still took the majority.[21]

More industrial estates and districts were created. This was because there was insufficient land for industrial development, leading to a rise in land rent. In 1971, every square metre of industrial land was sold at HK$1,329.09 at auction.[21] In this period, industrial areas were spread all over the city, especially in the New Territories, where new towns, such as Tuen Mun and Shatin, were built. A hire-purchase plan was also adopted to relieve pressure from buying land for industrial uses.[22]

Hong Kong managed to maintain its increasing manufacturing rate while diversifying manufacturing. In the 1970s, Hong Kong's factories increased from 16,500 to 22,200. The number of workers increased from 549,000 to 871,000. The value of exports increased from $1,234,700,000 to $5,591,200,000, and increased by 18.18% every year.[22]

The textile industry prospered during the 1970s. The city was the largest supplier of denim. Most of its manufacturers utilised shuttleless weaving machines and there were a total of 29,577 weaving machines.[23] Shoe-makers started to produce leather shoes rather than the cheap shoes of the 1960s.[24] Major clothing companies also emerged[25] and quartz watches were first made during this period.[26]

Industrial relocation

Formation

In the 1980s, the labour-intensive industries of Hong Kong, which depended on the city's low costs to remain competitive, faced the problem of increasing land rents and labour costs.[22] Moreover, the increase of population did not suffice as the demand for products grew.[27] Compared to the other three Asian Tigers, Hong Kong's capital-intensive and technology-intensive industries were undeveloped and some less developed countries, such as Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia, exceeded Hong Kong in the labour-intensive field. Another problem was the increasing protectionism of Western countries, causing some privileges to be removed and extra restrictions placed on Hong Kong products.[22]

Meanwhile, the economic reforms in Mainland China provided a favourable condition for building factories there.[28][29] Mainland China had labour and land and looser pollution control than Hong Kong. The average daily wage of Hong Kong was HK$65 in 1981, compared to HK$2 in Guangdong in 1980. Mainland China's infrastructure and facilities were less developed than Hong Kong, further cutting costs.[30] It also has a lot of flat land for industrial development[29] and a large local market.[29] Therefore, Hong Kong industrialists took advantage of Mainland China's pull factors by relocating their factories there.[31]

Most factories relocated to the Pearl River Delta. The roads, ports and communication networks of the Pearl River Delta were rapid, and places such as Guangzhou and Foshan had good light industry bases. According to government estimates, among the relocated factories, 94% of them relocated to Guangdong from 1989 to 1992. Among those, 43% relocated to Shenzhen and 17% to Dongguan. However, industrial relocation was not limited to Mainland China.[32] Some industrialists relocated their factories to nearby countries such as Thailand,[32] India, the Philippines, Myanmar, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Malaysia.[31]

Two individual terms were coined. The first, 'made in Hong Kong', refers to the process in which all power, resources (apart from raw materials imported from foreign countries), labour, capital, design and management occur in Hong Kong, and the products are either sold locally or exported overseas. This system is a pre-relocation manufacturing system. The second, 'made by Hong Kong', refers to the process in which capital, design, management and office occur in Hong Kong. However, the power and labour are supplied from Mainland China where the factories are located. Raw materials are transported to Mainland China via Hong Kong. The products are then shipped to overseas countries. This system describes the system that the relocated factories follow.[33]

The first factories were relocated to Mainland China in the late 1970s. The relocation trend reached its peak in the mid-1980s. By the 1990s, over 80% of the factories had been relocated to Mainland China. The value of domestic exports continued to decrease while that of re-exportation from Mainland China increased drastically. In the toy industry, only 7% of the value of exports was gained by domestic exports, while 93% was re-exported from Mainland China. From 1989 to 1994, the value of re-exportation from Mainland China increased by 25.6% annually on average.[28] In the 1990s, the jewellery industry moved most of their manufacturing process to Mainland with the exception of the most valuable jewellery production.[34]

Nevertheless, some factories remained in Hong Kong, either because of importation quotas or limits on place of origin, or because only Hong Kong had the technology required. Industries that produced a small number of high-quality goods need not be relocated. Some factories also remained because they had overseas branches.[32] Family workshops also stayed.[35]

Impacts

Industrial relocation has, to some extent, contributed to the upgrade of industries. The labour-intensive industries of Hong Kong were turned into capital-intensive and technology-intensive industries.[35] The relocated Mainland factories became more effective than before their relocation thus increasing the productivity of the manufacturers. From 1985 to 2004, the total amount made by such manufacturers rose from HK$208,000 to HK$942,000.[36] Products produced in the Mainland are also more competitive due to low costs.[37]

The environment of Hong Kong has improved while that of Mainland China is heavily polluted. The Pearl River Delta faced serious water pollution and much farmland was turned into industrial uses. The primary industry of Guangdong decreased from 70.7% to only 32.9%, while that of the secondary industry rose from 12.2% to 20.7%. From 1988 to 2009, the area of rice fields dropped by 32%.[38] Consequently, local governments of South China passed laws to restrict industrial pollution.[39]

The livelihood of people in Mainland China has improved. Many people no longer need to farm for a living. In 1987, over a million workers were employed by Hong Kong industrialists (which increased to 10 million as of 2005[37]) in Mainland China.[27] Local governments in China earn money, which are used to improve the infrastructure of China, through land rent and taxes. Therefore, the economy of the Pearl River Delta was boosted alongside the improvement of living standards.[37]

As the manufacturing industry declined, the tertiary industry rose. The service sector continues to prosper to this day. In 1980, the tertiary sector took up only 48.4% of Hong Kong's employment structure.[36] By 2008, 87.1% of all employees worked in the service industry while employee rates of the manufacturing industry dropped to 4.6%.[40] The relocated factories needed support services including shipping, insurance, and above all, finance. Due to more people working in the tertiary sector, Hong Kong's economy grew increasingly reliant on service industries.[41]

The finance and real estate industries bloomed in the 1990s. However, the dependence on such industries caused a loss of competitiveness between products produced by Hong Kong-based manufacturers and those from the international market. The other Asian Tigers had developed capital-intensive industries such as crude oil, computers and heavy industries.[42] As a result, the government of Hong Kong has tried to develop knowledge-based, high-technology and higher-value-added industries. High-technology training programmes have been provided as well as courses related to information technology and biotechnology. Land was used for high-technology industries, notably Cyberport. Research centres have been set up to support such industries, notably the Hong Kong Science and Technology Park.[39] High-technology exports took up one-third of Hong Kong's total exports in 2005.[43] Manufacturing workers who are unskilled in other areas are unemployed as a result of industrial relocation.[37][44] To aid them, the government provided retraining programmes, allowing them, especially those in the tertiary industry, to get new jobs.[38]

21st century

As of 2008, the printing and publishing industry takes up 24.6% of the employment structure of the city's manufacturing sector, followed by the food and beverage industry at 17.5%. The textile, clothing and electronic industries took up only 9.8%, 8.7% and 7.6% respectively.[45] The clothing industry accounted for 35.6% of the value of domestic exports of the manufacturing sector in 2007, while the electronics industry took up 18.0% of it. Chemical products, jewellery, textiles, and printing and publishing industries took up 9.8%, 8.0%, 3.3%, and 2.6% respectively.[46]

Despite the relocation of light and labour-intensive industries, heavy industries are still rare in Hong Kong.[47] The large population of Hong Kong remains favourable for labour-intensive industries, the raw materials and products of light industries are easier to transport than the heavy industries, and there is insufficient flat land in Hong Kong for heavy industries.[47]

In the 21st century, industrialists in Shenzhen have expressed interest in cooperating with Hong Kong in high-technology manufacturing industries. They want to share business-related information with Hong Kong and use the city's financial services such as the electronics industry. Quaternary industries such as the software industry and tertiary industries such as environmental protection companies are also interested.[48]

On 11 August 2020, the United States customs announced that goods manufactured in Hong Kong and imported into the US after September 25 must be labeled "Made In China" instead of "Made In Hong Kong".[49]

References and footnotes

Footnotes

- 封, p.28

- 封, p.27

- Zhang 1999, p.227

- Zhang 1996, p.140

- Zhang 1996, p.141

- Zhang 1999, p.229

- 何, p.11

- Zhang 1996, p.141

- 何, p.2

- 封, p.29

- 何, p.12

- 何, p.3

- 封, p.30

- 何, p. 23

- 何, p.71

- 何, p.55

- 何, p.15

- Ip, Lam, and Wong, p.10

- 封, p.31

- 封, p.32

- 封, p.33

- 封, p.34

- 何, p.22

- 何, p.35

- 何, p.38

- 何, p.57

- Kristof

- 封, p.35

- Keung

- Ip, Lam and Wong, p.20

- Ip, Lam and Wong, p.15

- 封, p.36

- Ip, Lam, and Wong, p.16

- 何, p.884

- 封, p.37

- Ip, Lam and Wong, p.26

- Ip, Lam and Wong, p.28

- Ip, Lam and Wong, p.30

- Ip, Lam and Wong, p.31

- Hong Kong Yearbook, p.124

- 何, p.88

- 何, p.112

- Lau, p.ii

- 何, p.99

- Hong Kong Yearbook, p.98

- Hong Kong Yearbook 2007, p.102

- Ip, Lam and Wong, p.8

- Lau, p.iii

- "Country of Origin Marking of Products of Hong Kong". Federal Register. 2020-08-11. Retrieved 2020-08-12.

References

- Ip, Kim Wai; Lam, Chi Chung; Wong, Kam Fai (2007). Exploring Geography. 1B (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 8–35. ISBN 978-0-19-548660-5.

- 何, 耀生 (2009). 香港製造‧製造香港 [Made in Hong Kong — Making Hong Kong] (in Chinese) (1st ed.). 明報出版社有限公司. pp. 1–153. ISBN 978-962-8994-99-1.

- 封, 小雲; 龔, 唯平 (1997). 香港工業2000 [Hong Kong Industries 2000] (in Chinese) (2nd ed.). Joint Publishing. ISBN 962-04-1382-2.

- Hong Kong Yearbook 2008. Government of Hong Kong. 2008.

- Hong Kong Yearbook 2007. Government of Hong Kong. 2007.

- Keung, Hon-ming. "工業北移 [Industries Moving to the North]". 地理入門 [Gateway to Geography] (in Chinese). HKEdCity. Retrieved 7 July 2010.

- Kristof, Nicholas D. (September 4, 1987). "China: Hong Kong's Factory". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- Zhang, Li (25 January 1999). "1937- 1941 年香港华资工业的发展 [Development of Chinese-owned Enterprises in Hong Kong from 1937 to 1941]" (PDF). Modern Chinese History Studies (in Chinese). China: China Academic Journal Electronic Publishing House (1). Retrieved 17 January 2013.

- Zhang, Xiaohui (25 January 1996). "近代香港的华资工业 [Chinese-owned Industries in Modern Hong Kong]" (PDF). Modern Chinese History Studies (in Chinese). China: China Academic Journal Electronic Publishing House (1). Retrieved 17 January 2013.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Industry in Hong Kong. |