Rattan

Rattan (from the Malay rotan) is the name for roughly 600 species of old world climbing palms belonging to subfamily Calamoideae.[1] Rattan is also known as manila, or malacca, named after the ports of shipment Manila and Malacca City, and as manau (from the Malay rotan manau, the trade name for Calamus manan canes in Southeast Asia).[2] The climbing habit is associated with the characteristics of its flexible woody stem, derived typically from a secondary growth, makes rattan a liana rather than a true wood.

.jpg.webp)

Rattan is known for its use in wickerwork furniture.

Taxonomy

Calamoideae also includes tree palms such as Raphia (Raffia) and Metroxylon (Sago palm) and shrub palms such as Salacca (Salak) (Uhl & Dransfield 1987 Genera Palmarum).[1] The climbing habit in palms is not restricted to Calamoideae, but has also evolved in three other evolutionary lines—tribes Cocoseae (Desmoncus with c. 7–10 species in the New World tropics) and Areceae (Dypsis scandens in Madagascar) in subfamily Arecoideae, and tribe Hyophorbeae (climbing species of the large genus Chamaedorea in Central America) in subfamily Ceroxyloideae.[3] They do not have spinose stems and climb by means of their reflexed terminal leaflets.[3] Of these only Desmoncus spp. furnish stems of sufficiently good quality to be used as rattan cane substitutes.[3]

There are 13 different genera of rattans that include around 600 species.[3] Some of the species in these "rattan genera" have a different habit and do not climb, they are shrubby palms of the forest undergrowth; nevertheless they are close relatives to species that are climbers and they are hence included in the same genera.[1][3] The largest rattan genus is Calamus, distributed in Asia except for one species represented in Africa.[3] From the remaining rattan genera, Daemonorops, Ceratolobus, Korthalsia, Plectocomia, Plectocomiopsis, Myrialepis, Calospatha, Pogonotium and Retispatha, are centered in Southeast Asia with outliers eastwards and northwards;[3] and three are endemic to Africa: Laccosperma (syn. Ancistrophyllum), Eremospatha and Oncocalamus.[3]

The rattan genera and their distribution (Uhl & Dransfield 1987 Genera Palmarum,[4] Dransfield 1992):[3]

| Genus | Number of species | Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Calamus L. | c. 370–400 | Tropical Africa, India and Sri Lanka, China, south and east to Fiji, Vanuatu and eastern Australia |

| Calospatha Becc. | 1 | Endemic to Peninsular Malaysia |

| Ceratolobus Bl. | 6 | Malay Peninsula, Sumatra, Borneo, Java |

| Daemonorops Bl. | c. 115 | India and China to westernmost New Guinea |

| Eremospatha (Mann & Wendl.) Wendl. | 10 | Humid tropical Africa |

| Korthalsia Bl. | c. 26 | Indo-China and Burma to New Guinea |

| Laccosperma (Mann & Wendl.) Drude | 5 | Humid tropical Africa |

| Myrialepis Becc. | 1 | Indo-China, Thailand, Burma, Peninsular Malaysia and Sumatra |

| Oncocalamus (Wendl.) Wendl. | 4 | Humid tropical Africa |

| Plectocomia Mart. | c. 16 | Himalayas and south China to western Malaysia |

| Plectocomiopsis Becc. | c. 5 | Laos, Thailand, Peninsular Malaysia, Borneo, Sumatra |

| Pogonotium J. Dransf. | 3 | Two species endemic to Borneo, one species in both Peninsular Malaysia and Borneo |

| Retispatha J. Dransf. | 1 | Endemic to Borneo |

In Uhl & Dransfield (1987 Genera Palmarum,[4] 2ºed. 2008), and also Dransfield & Manokaran (1993[5]), a great deal of basic introductory information is available.[1]

Available rattan floras and monographs by region (2002[3]):

| Region | Reference |

|---|---|

| Peninsular Malaysia | Dransfield, 1979[6] |

| Sabah | Dransfield, 1984[7] |

| Sarawak | Dransfield, 1992a[8] |

| Brunei | Dransfield, 1998[9] |

| Sri Lanka | de Zoysa & Vivekanandan, 1994[10] |

| India (general) | Basu, 1992[11] |

| India (Western Ghats) | Renuka, 1992[12] |

| India (south) | Lakshmana, 1993[13] |

| Andaman and Nicobar Islands | Renuka, 1995[14] |

| Bangladesh | Alam, 1990[15] |

| Papua New Guinea | Johns & Taurereko, 1989a,[16] 1989b[17] (preliminary notes only) |

| Irian Jaya | Currently (2002) under study at Kew (Baker & Dransfield) |

| Indonesia | Dransfield and Mogea [to 2002 in prep.]; more field work needed |

| Laos | Currently (2002) in prep. (Evans) |

| Thailand | Hodel, 1998[18] |

| Africa | Currently (2002) in prep. (Sunderland) |

Uses by taxon.

The major commercial species of rattan canes as identified for Asia by Dransfield and Manokaran (1993) and for Africa, by Tuley (1995) and Sunderland (1999) (Desmoncus not treated here):[3]

| Species | Distribution | Conservation status |

|---|---|---|

| Calamus caesius Bl. | Peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra, Borneo, Philippines and Thailand. Also introduced to China and south Pacific for planting | Unknown |

| Calamus egregius Burr. | Endemic to Hainan island, China, but introduced to southern China for cultivation | Unknown |

| Calamus exilis Griffith | Peninsular Malaysia and Sumatra | Not threatened |

| Calamus javensis Bl. | Widespread in Southeast Asia | Not threatened |

| Calamus manan Miq. | Peninsular Malaysia and Sumatra | Threatened |

| Calamus merrillii Becc. | Philippines | Threatened |

| Calamus mindorensis Becc. | Philippines | Unknown |

| Calamus optimus Becc. | Borneo and Sumatra. Cultivated in Kalimantan | Unknown |

| Calamus ornatus Bl. | Thailand, Sumatra, Java, Borneo, Sulawesi, to the Philippines | Unknown |

| Calamus ovoideus Thwaites ex Trimen | Western Sri Lanka | Threatened |

| Calamus palustris Griffith | Burma, southern China, to Malaysia and the Andaman Islands | Unknown |

| Calamus pogonacanthus Becc. ex Winkler | Borneo | Unknown |

| Calamus scipionum Loureiro | Burma, Thailand, Peninsular Malaysia, Sumatra, Borneo to Palawan | Unknown |

| Calamus simplicifolius Wei | Endemic to Hainan island, China, but introduced to southern China for cultivation | Unknown |

| Calamus subinermis (eddl. ex Becc. | Sabah, Sarawak, East Kalimantan and Palawan | Unknown |

| Calamus tetradactylus Hance | Southern China. Introduced to Malaysia | Unknown |

| Calamus trachycoleus Becc. | South and Central Kalimantan. Introduced into Malaysia for cultivation | Not threatened |

| Calamus tumidus Furtado | Peninsular Malaysia and Sumatra | Unknown |

| Calamus wailong Pei & Chen | Southern China | Unknown |

| Calamus zollingeri Becc. | Sulawesi and the Moluccas | Unknown |

| Daemonorops jenkinsiana (Hance) Becc. | Southern China | Unknown |

| Daemonorops robusta Warb. | Indonesia, Sulawesi and the Moluccas | Unknown |

| Daemonorops sabut Becc. | Peninsula Malaysia and Borneo | Unknown |

| Eremospatha macrocarpa (Mann & Wendl.) Mann & Wendl. | Tropical Africa from Sierra Leone to Angola | Not threatened |

| Eremospatha haullevilleana de Wild. | Congo Basin to East Africa | - |

| Laccosperma robustum (Burr.) J. Dransf. | Cameroon to Congo Basin | - |

| Laccosperma secundiflorum (P. Beauv.) Mann & Wendl. | Tropical Africa from Sierra Leone to Angola | Not threatened |

Utilized Calamus species canes:[19]

| Species of Calamus | Notes of utilization |

|---|---|

| Calamus acanthospathus Griff. | Canes for bridge cables, basketry |

| Calamus andamanicus Kurz | Excellent large-diameter canes harvested for furniture industry; leaves for thatching |

| Calamus aruensis Becc. | Excellent quality medium- to large-diameter canes for furniture |

| Calamus arugda Becc. | Entire canes for handicrafts, furniture, basketry, etc., local and export markets |

| Calamus axillaris Becc. | Small-diameter canes for basketry, fish traps and tying |

| Calamus bacularis Becc. | Canes for walking-sticks |

| Calamus bicolor Becc. | Ornamental use of young plants |

| Calamus blumei Becc. | Canes of good quality but quantities insufficient for commercial use; canes for baskets and mats |

| Calamus boniensis Becc. ex Heyne | Probably sold together with other small-diameter canes |

| Calamus burckianus Becc. | Canes for broom handles |

| Calamus caesius Bl. | Canes for commercial and traditional uses |

| Calamus castaneus Becc. | Leaves for thatch; immature fruits in traditional medicine |

| Calamus ciliaris Bl. | Slender canes for weaving and binding; seedlings used as ornamentals |

| Calamus conirostris Becc. | Canes of poor quality, rarely used; fruit eaten |

| Calamus convallium J. Dransf. | Canes |

| Calamus cumingianus Becc. | Entire canes made into handicrafts, furniture and baskets |

| Calamus deërratus G. Mann & H. Wendl. | Canes for construction and weaving |

| Calamus densiflorus Becc. | Canes for making furniture and baskets |

| Calamus didymocarpus Warb. ex Becc. | Canes inferior but used for local furniture-making |

| Calamus diepenhorstii Miq. | Canes for tying, cordage, basketry, fish traps and noose traps |

| Calamus dimorphacanthus Becc. var. dimorphacanthus | Canes used for baskets, bags, tying, etc. for home industries |

| Calamus discolor Becc. | Young plants as ornamentals; canes for binding or tying |

| Calamus egregius Burr. | Excellent small- to medium-diameter canes for binding and weaving in furniture; new shoots edible |

| Calamus elmerianus Becc. | Canes for furniture, handicrafts and home industries |

| Calamus erioacanthus Becc. | Canes of good quality |

| Calamus exilis Griff. | Canes for binding, weaving, basketry, handicrafts |

| Calamus flabellatus Becc. | Canes for tying, binding and weaving |

| Calamus gamblei Becc. | Canes for furniture |

| Calamus gibbsianus Becc. | Canes for tying and weaving |

| Calamus gonospermus Becc. | Edible fruit |

| Calamus gracilis Roxb. | Canes for handicrafts |

| Calamus grandifolius Becc. | Canes for furniture |

| Calamus guruba (Buch-Ham) ex Mart. | Canes for basketry, chair seats |

| Calamus halconensis (Becc.) Baja-Lapis var. dimorphacanthus Becc. | Canes for chair frames, cables for ferry boats, hauling logs and as rigging on small sailboats; split canes for mats, basketry, fish traps, chair seats |

| Calamus heteroideus Bl. | Canes for cordage |

| Calamus hispidulus Becc. | Canes for weaving |

| Calamus hookerianus Becc. | Canes for furniture, basketry |

| Calamus huegelianus Mart. | Canes for basketry, chair frames, etc. |

| Calamus inermis T. Anders. | Canes for police sticks, chair frames |

| Calamus inops Becc. ex Heyne | Actual use of small- to medium-diameter canes not known |

| Calamus insignis Becc. | Split canes for basketry, cordage; spiny leaf-sheaths as food graters |

| Calamus javensis Bl. | Canes for cordage, basketry, noose traps, musical instruments; edible raw cabbage as medicine; spiny leaf-sheaths formerly used to make food graters |

| Calamus koordersianus Becc. | Canes locally for basket frames |

| Calamus laevigatus Mart. | Extensively collected as small-diameter cane, end-uses not documented |

| Calamus latifolius Roxb. | Canes for basketry, walking-sticks, furniture frames; split canes for chair seats |

| Calamus leiocaulis Becc. ex Heyne | Small-diameter canes extensively used to make furniture for local and export markets |

| Calamus leptospadix Griff. | Canes for basketry and chair seats |

| Calamus leptostachys Becc. ex Heyne | Excellent small-diameter canes for furniture and handicrafts for local and export markets |

| Calamus longisetus Griff. | Coarse cane for furniture; leaves for thatch; edible fruit |

| Calamus longispathus Ridl. | Young leaves occasionally as cigarette paper; fruits as medicine |

| Calamus luridus Becc. | Canes split for tying and binding |

| Calamus manan Miq. | Most desirable large-diameter canes for furniture |

| Calamus manillensis (Mart.) H. Wendl. | Edible fruit; canes of inferior quality for tying |

| Calamus marginatus (Bl.) Mart. | Poor quality but durable canes for basket frames and walking-sticks |

| Calamus mattanensis Becc. | Canes occasionally used to make coarse baskets |

| Calamus megaphyllus Becc. | Canes for basketry and tying |

| Calamus melanorhynchus Becc. | Canes for basketry and handicrafts |

| Calamus merrillii Becc. | Entire canes for chair frames, ferry boat cables, hauling logs, sailboat rigging; split canes for basketry, chairs, fish traps, etc. |

| Calamus microcarpus Becc. | Canes for basketry |

| Calamus microsphaerion Becc. | Entire canes for basketry |

| Calamus minahassae Becc. | Canes as cordage |

| Calamus mindorensis Becc. | Popular large-diameter canes for furniture; split canes for basketry, cordage |

| Calamus mitis Becc. | Canes for basketry and tying |

| Calamus moseleyanus Becc. | Canes for furniture |

| Calamus multinervis Becc. | Canes for furniture |

| Calamus muricatus Becc. | Cabbage eaten |

| Calamus myriacanthus Becc. | Canes for walking-sticks, cages, basket frames |

| Calamus nagbettai Fernandez & Dey | Canes for basketry |

| Calamus nambariensis Becc. | Canes for handicrafts |

| Calamus optimus Becc. | Canes used to make mats, for weaving, to bind furniture and cordage |

| Calamus ornatus Bl. | Major use of canes for furniture; also for walking-sticks, handles for implements and flooring; leaves, cabbage and roots as medicine; fruits occasionally eaten |

| Calamus ovoideus Thwaites ex Trimen | Split canes for basketry; entire canes for furniture frames; split cane cores for crude woven products |

| Calamus oxleyanus Teysm. & Binnend. ex Miq. | Canes for walking-sticks |

| Calamus palustris Griff. | Canes excellent for furniture frames |

| Calamus pandanosmus Furt. | Canes |

| Calamus paspalanthus Becc. | Seedlings as potential ornamental; ripe fruit pickled and young shoot eaten |

| Calamus pedicellatus Becc. ex Heyne | Canes apparently of good quality for furniture |

| Calamus perakensis Becc. | Canes occasionally used for walking-sticks |

| Calamus peregrinus Furt. | Robust canes of good quality for furniture |

| Calamus pilosellus Becc. | Canes of good appearance but probably only for local use |

| Calamus pogonacanthus Becc. ex H. Winkler | Canes of good quality for tying, binding and making coarse mats |

| Calamus poilanei Conrad | Canes for handicrafts |

| Calamus polystachys Becc. | Coarse canes used for broom handles |

| Calamus pseudorivalis Becc. | Canes for furniture |

| Calamus pseudotenuis Becc. | Canes for basketry |

| Calamus pseudoulur Becc. | Canes for basketry, etc. |

| Calamus ramulosus Becc. | Canes for furniture |

| Calamus reyesianus Becc. | Canes of small diameter use for furniture and basketry, local and international |

| Calamus rhomboideus Bl. | Canes possibly used to make baskets and mats |

| Calamus rhytidomus Becc. | Canes used locally for binding |

| Calamus rotang Linn. | Canes for basketry, chair seats |

| Calamus rudentum Lour. | Canes for handicrafts; edible fruit |

| Calamus ruvidus Becc. | Canes used for basketry and tying |

| Calamus scabridulus Becc. | Canes split for tying, thatching and cordage |

| Calamus scipionum Lour. | Canes for making moderate-quality furniture; walking-sticks, umbrella handles, etc. |

| Calamus sedens J. Dransf. | Canes sometimes used to make walking-sticks |

| Calamus semoi Becc. | Excellent quality cane; under cultivation in gardens |

| Calamus simplex Becc. | Canes for basketry |

| Calamus simplicifolius Wei | Good medium-diameter cane for furniture, binding, weaving, basketry, etc.; new shoots edible |

| Calamus siphonospathus Mart. | Canes for basketry and tying |

| Calamus solitarius T. Evans et al. | Canes for handicrafts |

| Calamus spinifolius Becc. | Canes for basketry and tying |

| Calamus subinermis H. Wendl. ex Becc. | Canes for furniture frames; cabbage cooked as a vegetable; fruit sometimes eaten |

| Calamus symphysipus Becc. | Canes for furniture |

| Calamus tenuis Roxb. | Canes for basketry; fruits and young shoots eaten |

| Calamus tetradactylus Hance | Small-diameter canes for handicrafts, basketry and furniture |

| Calamus thwaitesii Becc. | Canes for furniture |

| Calamus tomentosus Becc. | Canes for tying and binding |

| Calamus trachycoleus Becc. | Canes used as skin peels for weaving chair seats and back; unsplit for furniture; basketry, mats, fish traps, cordage |

| Calamus travancoricus Bedd. ex Becc. & Hook | Canes for handicrafts and furniture |

| Calamus trispermus Becc. | Canes for furniture |

| Calamus tumidus Furt. | Canes for furniture |

| Calamus ulur Becc. | Split canes for cordage |

| Calamus unifarius H. Wendl. | Canes locally for furniture |

| Calamus usitatus Becc. | Canes for basketry, furniture and handicrafts |

| Calamus vidalianus Becc. | Canes for furniture |

| Calamus viminalis Willd. | Canes locally for basketry and matting |

| Calamus wailong S.J. Pei & S.Y. Chen | Canes for weaving and furniture |

| Calamus warburgii K. Schum. | Canes locally for basket frames |

| Calamus ollingeri Becc. | Canes for furniture frames |

Other traditional uses of rattans by species:[3]

| Product / Use | Species |

|---|---|

| Fruit eaten | Calamus conirostris; Calamus longisetus; Calamus manillensis; Calamus merrillii; Calamus ornatus; Calamus paspalanthus; Calamus subinermis; Calamus viminalis; Calospatha scortechinii; Daemonoropsingens; Daemonoropsingens periacantha; Daemonoropsingens ruptilis |

| Palm heart eaten | Calamus deerratus; Calamus egregius; Calamus javensis; Calamus muricatus; Calamus paspalanthus; Calamus siamensis; Calamus simplicifolius; Calamus subinermis; Calamus tenuis; Calamus viminalis; Daemonorops fissa; Daemonorops longispatha; Daemonorops margaritae; Daemonorops melanochaetes; Daemonorops periacantha; Daemonorops scapigera; Daemonorops schmidtiana; Daemonorops sparsiflora; Laccosperma secundiflorum; Plectocompiopsis geminiflora (and Daemonorops jenkinsiana.[20]) |

| Fruit used in traditional medicine | Calamus castaneus; Calamus longispathus; Daemonorops didymophylla |

| Palm heart in traditional medicine | Calamus exilis; Calamus javensis; Calamus ornatus; Daemonorops grandis; Korthalsia rigida |

| Fruit as source of red resin exuded between scales, used medicinally and as a dye (one source of "dragon's blood") | Daemonorops didymophylla; Daemonorops draco; Daemonorops maculata; Daemonorops micrantha; Daemonorops propinqua; Daemonorops rubra |

| Leaves for thatching | Calamus andamanicus; Calamus castaneus; Calamus longisetus; Daemonorops calicarpa; Daemonorops elongata; Daemonorops grandis; Daemonorops ingens; Daemonorops manii |

| Leaflet as cigarette paper | Calamus longispathus; Daemonorops leptopus |

| Leaves chewed as vermifuge | Laccosperma secundiflorum |

| Roots used as treatment for syphilis | Eremospatha macrocarpa |

| Leaf sheath used as toothbrush | Eremospatha wendlandiana; Oncocalamus sp. |

| Leaf sheath/petiole as grater | Calamus sp. (undescribed sp. from Bali); |

| Rachis for fishing pole | Daemonorops grandis; Laccosperma secundiflorum |

Structure

Most rattans differ from other palms in having slender stems, 2–5 cm (3⁄4–2 inches) diameter, with long internodes between the leaves; also, they are not trees but are vine-like lianas, scrambling through and over other vegetation. Rattans are also superficially similar to bamboo. Unlike bamboo, rattan stems ("malacca") are solid, and most species need structural support and cannot stand on their own. Many rattans have spines which act as hooks to aid climbing over other plants, and to deter herbivores. Rattans have been known to grow up to hundreds of metres long. Most (70%) of the world's rattan population exist in Indonesia, distributed among the islands Borneo, Sulawesi, and Sumbawa. The rest of the world's supply comes from the Philippines, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, and Bangladesh.

Economic and environmental issues

In forests where rattan grows, its economic value can help protect forest land, by providing an alternative to loggers who forgo timber logging and harvest rattan canes instead. Rattan is much easier to harvest, requires simpler tools and is much easier to transport. It also grows much faster than most tropical wood. This makes it a potential tool in forest maintenance, since it provides a profitable crop that depends on rather than replaces trees. It remains to be seen whether rattan can be as profitable or useful as the alternatives.

Rattans are threatened with overexploitation, as harvesters are cutting stems too young and reducing their ability to resprout.[21] Unsustainable harvesting of rattan can lead to forest degradation, affecting overall forest ecosystem services. Processing can also be polluting. The use of toxic chemicals and petrol in the processing of rattan affects soil, air and water resources, and also ultimately people's health. Meanwhile, the conventional method of rattan production is threatening the plant's long-term supply, and the income of workers.[22]

Uses

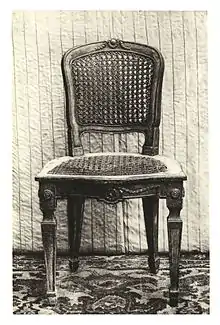

Rattan chair

Rattans are extensively used for making baskets and furniture. When cut into sections, rattan can be used as wood to make furniture. Rattan accepts paints and stains like many other kinds of wood, so it is available in many colours, and it can be worked into many styles. Moreover, the inner core can be separated and worked into wicker.

Generally, raw rattan is processed into several products to be used as materials in furniture making. From a strand of rattan, the skin is usually peeled off, to be used as rattan weaving material. The remaining "core" of the rattan can be used for various purposes in furniture making. Rattan is a very good material, mainly because it is lightweight, durable, and, to a certain extent, flexible and suitable for outdoor use.[23]

Clothing

Traditionally, the women of the Wemale ethnic group of Seram Island, Indonesia wore rattan girdles around their waist.[24]

Corporal punishment

Thin rattan canes were the standard implement for school corporal punishment in England and Wales, and are still used for this purpose in schools in Malaysia, Singapore, and several African countries. The usual maximum number of strokes was six, traditionally referred to as getting "Six of the best". Similar canes are used for military punishments in the Singapore Armed Forces.[25] Heavier canes, also of rattan, are used for judicial corporal punishments in Aceh, Brunei, Malaysia, and Singapore.[26]

Food source

Some rattan fruits are edible, with a sour taste akin to citrus. The fruit of some rattans exudes a red resin called dragon's blood; this resin was thought to have medicinal properties in antiquity and was used as a dye for violins, among other things.[27] The resin normally results in a wood with a light peach hue. In the Indian state of Assam, the shoot is also used as vegetable.

Medicinal potential

In early 2010, scientists in Italy announced that rattan wood would be used in a new "wood to bone" process for the production of artificial bone. The process takes small pieces of rattan and places it in a furnace. Calcium and carbon are added. The wood is then further heated under intense pressure in another oven-like machine, and a phosphate solution is introduced. This process produces almost an exact replica of bone material. The process takes about 10 days. At the time of the announcement the bone was being tested in sheep, and there had been no signs of rejection. Particles from the sheep's bodies have migrated to the "wood bone" and formed long, continuous bones. The new bone-from-wood programme is being funded by the European Union. Implants into humans were anticipated to start in 2015.[28]

Wicks

Rattan is the preferred natural material used to wick essential oils in aroma reed diffusers (commonly used in aromatherapy, or merely to scent closets, passageways, and rooms), because each rattan reed contains 20 or more permeable channels that wick the oil from the container up the stem and release fragrance into the air, through an evaporation diffusion process. In contrast, reeds made from bamboo contain nodes that inhibit the passage of essential oils.[29][30][31]

Handicraft and arts

Many of the properties of rattan that make it suitable for furniture also make it a popular choice for handicraft and art pieces. Uses include rattan baskets, plant containers, and other decorative works.

Due to its durability and resistance to splintering, sections of rattan can be used as canes, crooks for high-end umbrellas, or staves for martial arts. Rattan sticks 70 cm (28 inches) long, called baston, are used in Filipino martial arts, especially Arnis/Eskrima/Kali and for the striking weapons in the Society for Creative Anachronism's full-contact "armoured combat".[32][33]

Along with birch and bamboo, rattan is a common material used for the handles in percussion mallets, especially mallets for keyboard percussion, e.g., marimba, vibraphone, xylophone, etc.

Indonesians making rattan furniture, circa 1948

Indonesians making rattan furniture, circa 1948 A rattan chair

A rattan chair A rattan ball of Sepak takraw

A rattan ball of Sepak takraw

Shelter material

Most natives or locals from the rattan rich countries employ the aid of this sturdy plant in their home building projects. It is heavily used as a housing material in rural areas. The skin of the plant or wood is primarily used for weaving.

Sports equipment

Rattan cane is also used traditionally to make polo mallets, though only a small portion of cane harvested (roughly 3%) is strong, flexible, and durable enough to be made into sticks for polo mallets, and popularity of rattan mallets is waning next the more modern variant, fibrecanes.

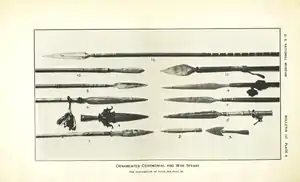

Weaponry

Fire-hardened rattan were commonly used as the shafts of Philippine spears collectively known as sibat. They were fitted with a variety of iron spearheads and ranged from short throwing versions to heavy thrusting weapons. They were used for hunting, fishing, or warfare (both land and naval warfare). The rattan shafts of war spears are usually elaborately ornamented with carvings and metal inlays.[34] Arnis also makes prominent use of rattan as "arnis sticks", commonly called yantok or baston. Their durability and weight makes it ideal for training with complex execution of techniques as well as being a choice of weapon, even against bladed objects.[35]

It sees also prominent use in battle re-enactments as stand-ins to potentially lethal weapons.[36]

Rattan can also be used to build a functional sword that delivers a non-lethal but similar impact compared to steel counterparts.[37]

References

- J Dransfield. 2002. General Introduction to Rattan - The Biological Background to Exploitation and the History of Rattan Research. http://www.fao.org/docrep/003/y2783e/y2783e06.htm#P889_66944

- Johnson, Dennis V. (2004): Rattan Glossary: And Compendium Glossary with Emphasis on Africa. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, p. 22.

- Terry C.H. Sunderland and John Dransfield. Species Profiles. Ratans. http://www.fao.org/docrep/003/y2783e/y2783e05.htm

- Uhl, N.W. & Dransfield, J., 1987. Genera palmarum: a classification of palms based on the work of H.E.Moore Jr. pp 610. The International Palm Society & the Bailey Hortorium, Kansas.

- Dransfield, J. & Manokaran, N. (eds), 1993. Rattans. PROSEA volume 6. Pudoc, Wageningen. pp 137.

- Dransfield, J., 1979. A Manual of the Rattans of the Malay Peninsula. Malayan Forest Records No. 29. Forestry Department. Malaysia.

- Dransfield, J., 1984. The rattans of Sabah. Sabah Forest Record No. 13. Forestry Department, Malaysia.

- Dransfield, J., 1992a. The Rattans of Sarawak. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Sarawak Forest Department.

- Dransfield, J., 1998. The rattans of Brunei Darussalam. Forestry Department, Brunei Darussalam and the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK.

- De Zoysa, N. & K. Vivekenandan, 1994. Rattans of Sri Lanka. Sri Lanka Forest Department. Batteramulla.

- Basu, S.K., 1992. Rattan (canes) in India: a monographic revision. Rattan Information Centre. Kuala Lumpur.

- Renuka, C., 1992. Rattans of the Western Ghats: A Taxonomic Manual. Kerala Forest Research Institute, India.

- Lakshmana, A.C., 1993. The rattans of South India. Evergreen Publishers. Bangalore. India.

- Renuka, C., 1995. A manual of the rattans of the Andaman and Nicobar islands. Kerala Forest Research Insititute, India.

- Alam, M.K., 1990. The rattans of Bangladesh. Bangladesh Forest Research Institute. Dhaka.

- Johns, R. & R. Taurereko, 1989a. A preliminary checklist of the collections of Calamus and Daemonorops from the Papuan region. Rattan Research Report 1989/2.

- Johns, R. & R. Taurereko, 1989b. A guide to the collection and description of Calamus (Palmae) from Papuasia. Rattan Research Report 1989/3

- Hodel, D., 1998. The palms and cycads of Thailand. Allen Press. Kansas. USA.

- Rattan Glossary. Appendix III. http://www.fao.org/docrep/006/Y5232E/y5232e07.htm#P5059_100907 In: RATTAN glossary and Compendium glossary with emphasis on Africa. NON-WOOD FOREST PRODUCTS 16. FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

- Rattan Glossary. http://www.fao.org/docrep/006/Y5232E/y5232e04.htm#P31_5904 In: RATTAN glossary and Compendium glossary with emphasis on Africa. NON-WOOD FOREST PRODUCTS 16. FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. http://www.fao.org/docrep/006/Y5232E/y5232e00.htm#TopOfPage

- MacKinnon, K. (1998) Sustainable use as a conservation tool in the forests of South-East Asia. Conservation of Biological Resources (E.J. Milner Gulland & R Mace, eds), pp 174–192. Blackwell Science, Oxford.

- "WWF Rattan Switch project". WWF. July 2010. Archived from the original on 3 August 2010. Retrieved 16 July 2010.

- "THE RESOURCE, ITS USES AND PRESENT ACTION PROGRAMMES". www.fao.org. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Piper, Jaqueline M. (1995). Bamboo and rattan, traditional uses and beliefs. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195889987.

- "Singapore: Caning in the military forces". World Corporal Punishment Research. January 2019. (Includes a photograph of a military caning in progress)

- "Judicial caning in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei". World Corporal Punishment Research. January 2019.

- "Rattan". Encyclopedia.com.

- "Turning wood into bones". BBC News. 8 January 2010. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- "FAQS: Questions: Question 3". The Diffusery.

- "FAQS: Questions: Question 2". Avotion.

- "How To Choose The Best Diffuser Reeds". Reed Diffuser Guide.

- "What is the SCA?". Society for Creative Anachronism, Inc. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

Since we prefer that no one gets hurt, SCA combatants wear real armor and use rattan swords.

- Marshals' Handbook (PDF) (March 2007 revision ed.). Society for Creative Anachronism. March 2007. Retrieved 16 March 2010.

- Krieger, Herbert W. (1926). "The Collection of Primitive Weapons and Armor of the Philippine Islands in the United States National Museum, Smithsonian Institution". United States National Museum Bulletin. 137.

- "Why use Rattan?". 16 January 2015.

- "Blog".

- "A Commonplace Book: Building a Sword for Rattan Combat". 11 September 2007.

Further reading

- Siebert, Stephen F. (2012). The Nature and Culture of Rattan: Reflections on Vanishing Life in the Forests of Southeast Asia. University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3536-1.

External links

| Look up rattan in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.