Japanese occupation of Hong Kong

The Imperial Japanese occupation of Hong Kong began when the Governor of Hong Kong, Sir Mark Young, surrendered the British Crown colony of Hong Kong to the Empire of Japan on 25 December 1941. The surrender occurred after 18 days of fierce fighting against the overwhelming Japanese forces that had invaded the territory.[7][8] The occupation lasted for three years and eight months until Japan surrendered at the end of Second World War. The length of this period (三年零八個月) later became a metonym of the occupation.[8]

Hong Kong Occupied Territory | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1941–1945 | |||||||||

Anthem:

| |||||||||

The Hong Kong occupation zone (dark red) within the Empire of Japan (light red) at its furthest extent | |||||||||

| Status | Military occupation by the Empire of Japan | ||||||||

| Common languages | Japanese Cantonese | ||||||||

| Government | Military occupation | ||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||

• 1941–1945 | Hirohito | ||||||||

| Governor-General | |||||||||

• 1941–1942 | Takashi Sakai Masaichi Niimi | ||||||||

• 1942–1944 | Rensuke Isogai | ||||||||

• 1944–1945 | Hisakazu Tanaka | ||||||||

| Historical era | World War II | ||||||||

| 8–25 December 1941 | |||||||||

• Surrender of Hong Kong | 25 December 1941 | ||||||||

| 15 August 1945 | |||||||||

• Handover to the Royal Navy | 30 August 1945 | ||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

| 1941[2][3] | 1,042 km2 (402 sq mi) | ||||||||

| 1945[2][4] | 1,042 km2 (402 sq mi) | ||||||||

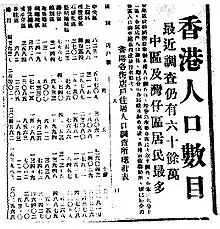

| Population | |||||||||

| 1,639,000 | |||||||||

| 600,000 | |||||||||

| Currency | Japanese military yen | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | China ∟ Hong Kong | ||||||||

| Japanese occupation of Hong Kong | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 香港日治時期 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 香港日治时期 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Background

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of Hong Kong |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| By topic |

|

Imperial Japanese invasion of China

During the Imperial Japanese military's full-scale invasion of China in 1937, Hong Kong as part of the British empire was not under attack. Nevertheless, its situation was influenced by the war in China due to proximity to the mainland China. In early March 1939, during an Imperial Japanese bombing raid on Shenzhen, a few bombs fell accidentally on Hong Kong territory, destroying a bridge and a train station.[9]

World War II

In 1936, Germany and the Empire of Japan signed the Anti-Comintern Pact. In 1937 Fascist Italy joined the pact, forming the core to what would become known as the Axis Powers.[10]

In the autumn of 1941, Nazi Germany was near the height of its military power. After the invasion of Poland and fall of France, German forces had overrun much of Western Europe and were racing towards Moscow.[11] The United States was neutral and opposition to Nazi Germany was given only by Britain, the British Commonwealth and the Soviet Union.[12]

The United States provided minor support to China in its fight against Imperial Japan's invasion. It imposed an embargo on the sale of oil to Japan after less aggressive forms of economic sanctions failed to halt Japanese advances.[13] On 7 December 1941 (Honolulu time), Japan entered World War II with the Japanese occupation of Malaya, as well as other attacks including attacking the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor and American-ruled Philippines, and the Japanese invasion of Thailand.

Battle of Hong Kong

As part of a general Pacific campaign, the Imperial Japanese launched an assault on Hong Kong on the morning of 8 December 1941.[14] British, Canadian, and Indian forces, supported by the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Forces attempted to resist the rapidly advancing Imperial Japanese, but were heavily outnumbered. After racing down the New Territories and Kowloon, Imperial Japanese forces crossed Victoria Harbour on 18 December.[15] After fierce fighting continued on Hong Kong Island, the only reservoir was lost. Canadian Winnipeg Grenadiers fought at the crucial Wong Nai Chung Gap that secured the passage between Victoria, Hong Kong and secluded southern sections of the island. Finally defeated, on 25 December 1941, British colonial officials headed by the Governor of Hong Kong Mark Aitchison Young surrendered at the Japanese headquarters.[2] To the local people, the day was known as "Black Christmas".[16]

The capitulation of Hong Kong was signed on the 26th at The Peninsula Hotel.[17] On 20 February 1942 General Rensuke Isogai became the first Imperial Japanese governor of Hong Kong.[18] Just before the British surrendered, drunken Imperial Japanese soldiers entered St. Stephen's College, which was being used as a hospital.[19] The Imperial Japanese then confronted two volunteer doctors and shot both of them, when entry was refused.[19] They then burst into the wards and attacked all of the wounded soldiers and medical staff who were unable to hide, in what was known as the St. Stephen's College incident.[19] This ushered in almost four years of Imperial Japanese administration.

Politics

Throughout the Imperial Japanese occupation, Hong Kong was ruled under martial law as an occupied territory.[20] Led by General Rensuke Isogai, the Japanese established their administrative centre and military headquarters at the Peninsula Hotel in Kowloon. The military government; comprising administrative, civilian affairs, economic, judicial, and naval departments; enacted stringent regulations and, through executive bureaus, exercised power over all residents of Hong Kong. They also set up the puppet Chinese Representative Council and Chinese Cooperative Council consisting of local leading Chinese and Eurasian community leaders.

In addition to Governor Mark Young, 7,000 British soldiers and civilians were kept in prisoner-of-war or internment camps, such as Sham Shui Po Prisoner Camp and Stanley Internment Camp.[21] Famine, malnourishment and sickness were pervasive. Severe cases of malnutrition among inmates occurred in the Stanley Internment Camp in 1945. Moreover, the Imperial Japanese military government blockaded Victoria Harbour and controlled warehouses.

Early in January 1942, former members of the Hong Kong Police, including Indians and Chinese, were recruited into a reformed police called the Kempeitai with new uniforms.[22] The police routinely performed executions at King's Park in Kowloon by using Chinese for beheading, shooting and bayonet practice.[22] The Imperial Japanese gendarmerie took over all police stations and organised the Police in five divisions, namely East Hong Kong, West Hong Kong, Kowloon, New Territories and Water Police. This force was headed by Colonel Noma Kennosuke. The headquarters was situated in the former Supreme Court Building.[23] Police in Hong Kong were under the organisation and control of the Imperial Japanese government. Imperial Japanese experts and administrators were chiefly employed in the Governor's Office and its various bureaus. Two councils of Chinese and Eurasian leaders were set up to manage the Chinese population.[22]

Economy

All trade and economic activities were strictly regulated by Japanese authorities, who took control of the majority of the factories. Having deprived vendors and banks of their possessions, the occupying forces outlawed the Hong Kong Dollar and replaced it with the Japanese Military Yen.[24] The exchange rate was fixed at 2 Hong Kong dollars to one military yen in January 1942.[25] Later, the yen was re-valued at 4 Hong Kong dollars to a yen in July 1942, which meant local people could exchange fewer military notes than before.[25] While the residents of Hong Kong were impoverished by the inequitable and forcibly imposed exchange rate, the Imperial Japanese government sold the Hong Kong Dollar to help finance their war-time economy. In June 1943, the military yen was made the sole legal tender. Prices of commodities for sale had to be marked in yen. Hyper-inflation then disrupted the economy, inflicting hardship upon the residents of the colony.[24] Enormous devaluation of the Imperial Japanese Military Yen after the war made it almost worthless.[17]

Public transportation and utilities unavoidably failed, owing to the shortage of fuel and the aerial bombardment of Hong Kong by the Americans. Tens of thousands of people became homeless and helpless, and many of them were employed in shipbuilding and construction. In the agricultural field, the Imperial Japanese took over the race track at Fanling and the air strip at Kam Tin for their rice-growing experiments.[7]:157, 159, 165[26]

With the intention of boosting the Imperial Japanese influence on Hong Kong, two Imperial Japanese banks, the Yokohama Specie Bank and the Bank of Taiwan, were re-opened.[7] These two banks replaced the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation (HSBC) and two other British banks responsible for issuing the banknotes.[7] They then liquidated various Allied banks.[7] British, American and Dutch bankers were forced to live in a small hotel, while some bankers who were viewed as enemies of the Imperial Japanese were executed. In May 1942, Imperial Japanese companies were encouraged to be set up. A Hong Kong trade syndicate consisting of Imperial Japanese firms was set up in October 1942 to manipulate overseas trade.[26]

Life under Japanese occupation

Life in fear

In order to cope with a lack of resources and the potential for Chinese residents of Hong Kong to support the allied forces in a possible invasion to retake the colony, the Japanese introduced a policy of forced deportation. As a result, the unemployed were deported to the Chinese mainland, and the population of Hong Kong dwindled from 1.6 million in 1941 to 600,000 in 1945.[27]

Furthermore, the Japanese modified the territory's infrastructure and landscape significantly in order to serve their wartime interests. In order to expand the Kai Tak Airport, for example, the Japanese demolished the Sung Wong Toi Monument in today's Kowloon City. Buildings of prestigious secondary schools such as Wah Yan College Hong Kong, which is one of the two Jesuit schools in Hong Kong, Diocesan Boys' School, the Central British School, the St. Paul's Girls' College of the Anglican church and de La Salle brothers' La Salle College were commandeered by occupying forces as military hospitals. It was rumoured that Diocesan Boys' School was used by the Japanese as an execution site.

Life was hard for people under Japanese rule. As there was inadequate food supply, the Japanese rationed necessities such as rice, oil, flour, salt and sugar. Each family was given a rationing licence, and every person could only buy 6.4 taels (240 g (8.5 oz)), of rice per day.[1] Most people did not have enough food to eat, and many died of starvation. The rationing system was abolished in 1944.

Atrocities

According to eyewitnesses, the Japanese committed atrocities against many local Chinese, including the rape of many Chinese women. During the three years and eight months of occupation, an estimated 10,000 Hong Kong civilians were executed, while many others were tortured, raped, or mutilated.[28]

On 19 December 1941, a group of Japanese soldiers killed ten St. John stretcher bearers at Wong Nai Chung Gap despite the fact that all the stretcher bearers wore the red cross armband. These soldiers captured a further five medics who were tied to a tree, two of whom were taken away by the soldiers, never to be seen again. The remaining three attempted to escape during the night, but only one survived the escape.[29] A team of amateur archaeologists found the remains of half of a badge. Evidence pointed to its belonging to Barclay, the captain of the Royal Army Medical Corps, therefore the archaeologists presented it to Barclay's son, Jim, who had never met his father before his death.[29] Other notable massacres near the end of the Battle of Hong Kong including the St. Stephen's College massacre.

Between the Surrender of Japan (15 August 1945) and formal surrender of Hong Kong to Rear Admiral Sir Cecil Harcourt (16 September 1945), fifteen Japanese soldiers arrested, tortured and executed around three hundred villagers of Sliver Mine District of Lantau Island as retaliation after being ambushed by Chinese guerrillas.[30] The incident was later referred as Silver Mine Bay massacre (銀礦灣大屠殺) by locals.

Charity and social services

During the occupation, hospitals available to the masses were limited. The Kowloon Hospital and Queen Mary Hospital were occupied by the Japanese army.[31] Despite the lack of medicine and funds, the Tung Wah and Kwong Wah Hospital continued their social services but to a limited scale. These included provision of food, medicine, clothing, and burial services. Although funds were provided, they still had great financial difficulties. Failure to collect rents and the high reparation costs forced them to promote fundraising activities like musical performances and dramas.

Tung Wah hospital and the charitable organisation Po Leung Kuk continued to provide charity relief, while substantial donations were given by members of the Chinese elite.[32] Po Leung Kuk also took in orphans, but were faced with financial problems during the occupation, as their bank deposits could not be withdrawn under Japanese control. Their services could only be continued through donations by Aw Boon Haw, a long-term financier of Po Leung Kuk.

Health and public hygiene

There were very few public hospitals during the Japanese occupation, as many of them were forcibly converted to military hospitals. Despite the inadequate supply of resources, Tung Wah Hospital and Kwong Wah Hospital still continuously offered limited social services to needy people. In June 1943, the management of water, gas and electricity was transferred into private Japanese hands.[7]

Education, press and political propaganda

Through schooling, mass media and other means of propaganda, the Japanese tried to foster favourable view amongst residents of the occupation. This process of Japanisation prevailed in many aspects of daily life.

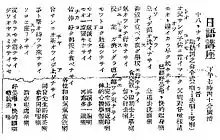

Japanese education

It was the Japanese conviction that education was key to securing their influence over the populace. The Japanese language became a mandatory subject in schools, and students who performed poorly in Japanese exams risked corporal punishment. According to a testimonial, English was forbidden from being taught and was not tolerated outside the classroom.[33] Some private Japanese language schools were established to promote oral Japanese. The Military Administration ran the Teachers' Training Course, and those teachers who failed a Japanese bench-mark test would need to take a three-month training course. The Japanese authorities tried to introduce Japanese traditions and customs to Hong Kong students through the Japanese lessons at school. Famous historical stories such as Mōri Motonari's "Sanbon no ya (Three Arrows)" and Xufu's (徐福) voyage to Japan were introduced in Japanese language textbooks.[34] The primary aim of the Japanisation of the education system was to facilitate Japanese control over the territory's populace in furtherence of the establishment of the Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere.

By 1943, in stark contrast to the successful imposition of the Japanese language upon the local populace, only one formal language school, the Bougok School (寳覺學校), was providing Cantonese language courses to Japanese people in Hong Kong. According to an instructor at the Bougok School, "teaching Cantonese is difficult because there is no system and set pattern in Cantonese grammar; and you have to change the pronunciation as the occasion demands" and "it would be easier for Cantonese people to learn Japanese than Japanese people to learn Cantonese".[35]

Propaganda

The Japanese promoted the use of Japanese as the lingua franca between the locals and the occupying forces. English shop signs and advertisements were banned and, in April 1942, streets and buildings in Central were renamed in Japanese. For example, Queen's Road became Meiji-dori and Des Voeux Road became Shōwa-dori.[7][36] Similarly, the Gloucester Hotel became the Matsubara.[37] The Peninsula Hotel, the Matsumoto;[38] Lane Crawford, Matsuzakaya.[39] The Queen's Theatre was renamed first the Nakajima-dori, then the Meiji.[39] Their propaganda also pointed to the pre-eminence of the Japanese way of life, of Japanese spiritual values and the ills of western materialism.

Government House, the residence of English governors prior to occupation, was the seat of power for the Japanese military governors. During the occupation, the buildings were largely reconstructed in 1944 following designs by Japanese engineer Siechi Fujimura, including the addition of a Japanese-style tower which remains to this day.[40] Many Georgian architectural features were removed during this period.[41] The roofs also continue to reflect a Japanese influence.[42]

The commemoration of Japanese festivals, state occasions, victories and anniversaries also strengthened the Japanese influence over Hong Kong. For instance, there was Yasukuri or Shrine Festival honouring the dead. There was also a Japanese Empire Day on 11 February 1943 centred around the worship of the Emperor Jimmu.[26]

Press and entertainment

The Hong Kong News, a pre-war Japanese-owned English newspaper, was revived in January 1942 during the Japanese occupation.[43] The editor, E.G. Ogura, was Japanese and the staff members were mainly Chinese and Portuguese who previously worked for the South China Morning Post.[33][43] It became the mouthpiece of the Japanese propaganda.[43] Ten local Chinese newspapers had been reduced to five in May. These newspapers were under press censorship. Radio sets were used for Japanese propaganda. Amusements still existed, though only for those who could afford them. The cinemas only screened Japanese films, such as The Battle of Hong Kong, the only film made in Hong Kong during the Japanese occupation.[44] Directed by Shigeo Tanaka (田中重雄 Tanaka Shigeo) and produced by the Dai Nippon Film Company, the film featured an all-Japanese cast but a few Hong Kong film personalities were also involved. This film appeared on the first anniversary of the attack.

Anti-Japanese resistance

The 38th Infantry Division, the unit mainly responsible for capturing Hong Kong, departed in January 1942. The Hong Kong Defence Force was established during the same month, and was the main Japanese military unit in Hong Kong throughout the occupation. The other Japanese military units stationed in Hong Kong from early 1942 were the small Hong Kong Artillery Force and the Imperial Japanese Navy's Hong Kong Base Force, which formed part of the 2nd China Expeditionary Fleet.[45]

East River Column

Originally formed by Zeng Sheng (曾生) in Guangdong in 1939, this group mainly comprised peasants, students, and seamen, including Yuan Geng.[2] When the war reached Hong Kong in 1941, the guerrilla force grew from 200 to more than 6,000 soldiers.[2] In January 1942, the Guangdong people's anti-Japanese East River guerrillas (廣東人民抗日游擊隊東江縱隊) was established to reinforce anti-Japanese forces in Dongjiang and Zhujiang Pearl River deltas.[46] The guerillas' most significant contribution to the Allies, in particular, was their rescue of twenty American pilots who parachuted into Kowloon when their planes were shot down by the Japanese.[2] In the wake of the British retreat, the guerillas picked up abandoned weapons and established bases in the New Territories and Kowloon.[2] Applying the tactics of guerrilla warfare, they killed Chinese traitors and collaborators.[2] They protected traders in Kowloon and Guangzhou, attacked the police station at Tai Po, and bombed Kai Tak Airport.[2] During the Japanese occupation the only fortified resistance was mounted by the East River guerillas.[2]

Hong Kong Kowloon brigade

In January 1942 the HK-Kowloon brigade (港九大隊) was established from the Guangdong People's anti-Japanese guerilla force.[47] In February 1942 with local residents Choi Kwok-Leung (蔡國梁) as commander and Chan Tat-Ming (陳達明) as political commissar, they were armed with 30 machine guns and several hundred rifles left by defeated British forces.[15] They numbered about 400 between 1942 and 1945 and operated in Sai Kung.[15] Additionally, the guerillas were noteworthy in rescuing prisoners-of-war, notably Sir Lindsay Ride, Sir Douglas Clague, Professor Gordan King, and David Bosanquet.[2] In December 1943 the Guangdong force reformed, with the East River guerillas absorbing the HK-Kowloon brigade into the larger unit.[47]

British Army Aid Group

The British Army Aid Group was formed in 1942 at the suggestion of Colonel Lindsay Ride.[15] The group rescued allied POWs including airmen shot down and workers trapped in the occupied colony.[15] It also developed a role in intelligence gathering.[15] In the process, the Group provided protection to the Dongjiang River which was a source for domestic water in Hong Kong. This was the first organisation in which Britons, Chinese and other nationalities served with no racial divide. Francis Lee Yiu-pui and Paul Tsui Ka-cheung were commissioned as officers.[15]

Air raids

United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) units based in China attacked the Hong Kong area from October 1942. Most of these raids involved a small number of aircraft, and typically targeted Japanese cargo ships which had been reported by Chinese guerrillas.[48] By January 1945 the city was being regularly raided by the USAAF.[49] The largest raid on Hong Kong took place on 16 January 1945 when, as part of the South China Sea raid, 471 United States Navy aircraft attacked shipping, harbour facilities and other targets.[50]

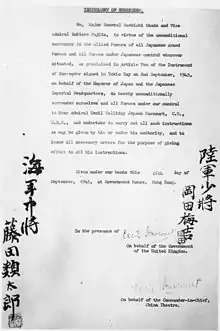

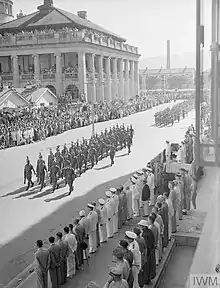

Japanese surrender

The Japanese occupation of Hong Kong ended in 1945, after Japan surrendered on 15 August 1945.[8][51][52] Hong Kong was handed over by the Imperial Japanese Army to the Royal Navy on 30 August 1945; British control over Hong Kong was thus restored. 30 August was declared as "Liberation Day" (Chinese: 重光紀念日), and was a public holiday in Hong Kong until 1997.

General Takashi Sakai, who led the invasion of Hong Kong and subsequently served as governor-general during the Japanese occupation, was tried as a war criminal, convicted and executed on the afternoon of 30 September 1946.[53]

Post-war political stage

In the aftermath of the Japanese surrender, it was unclear whether the United Kingdom or the Republic of China would assume sovereignty of the territory. The Kuomintang's Chiang Kai-shek assumed that China, including formerly European-occupied territories such as Hong Kong and Macau, would be re-unified under his rule.[20] Several years earlier, U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt insisted that colonialism would have to end, and promised Soong Mei-ling that Hong Kong would be restored to Chinese control.[54] However the British moved quickly to regain control of Hong Kong. As soon as he heard word of the Japanese surrender, Franklin Gimson, Hong Kong's colonial secretary, left his prison camp and declared himself the territory's acting governor.[2] A government office was set up at the Former French Mission Building in Victoria on 1 September 1945.[20] On 30 August 1945, British Rear Admiral Sir Cecil Halliday Jepson Harcourt sailed into Hong Kong on board the cruiser HMS Swiftsure to re-establish the British government's control over the colony.[20] Harcourt personally selected Chinese-Canadian Lt(N) William Lore of the Royal Canadian Navy as the first Allied officer ashore, in recognition of the sacrifices made by Canadian soldiers in the defence of Hong Kong.[55]

On 16 September 1945, Harcourt formally accepted the Japanese surrender[20] from Maj.-Gen. Umekichi Okada and Vice Admiral Ruitaro Fujita at Government House.[56]

Hong Kong's post-war recovery was astonishingly swift.[22] By November 1945, the economy had recovered so well that government controls were lifted and free markets restored. The population returned to around one million by early 1946 due to immigration from China.[22] Colonial taboos also broke down in the post-war years as European colonial powers realised that they could not administer their colonies as they did before the war. Chinese people were no longer forbidden from certain beaches, or from living on Victoria Peak.

References

- Fung, Chi Ming. [2005] (2005). Reluctant heroes: rickshaw pullers in Hong Kong and Canton, 1874–1954. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 962-209-734-0, ISBN 978-962-209-734-6. p.130, 135.

- Courtauld, Caroline. Holdsworth, May. [1997] (1997). The Hong Kong Story. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-590353-6. pp. 54–58.

- Stanford, David. [2006] (2006). Roses in December. Lulu press. ISBN 1-84753-966-1.

- Chan, Shun-hing. Leung, Beatrice. [2003] (2003). Changing Church and State Relations in Hong Kong, 1950–2000. Hong Kong: HK university press. p. 24. ISBN 962-209-612-3.

- Stanford, David. [2006] (2006). Roses in December. Lulu press. ISBN 1-84753-966-1.

- Chan, Shun-hing. Leung, Beatrice. [2003] (2003). Changing Church and State Relations in Hong Kong, 1950–2000. Hong Kong: HK university press. p. 24. ISBN 962-209-612-3.

- Snow, Philip. [2004] (2004). The fall of Hong Kong: Britain, China and the Japanese occupation. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10373-5, ISBN 978-0-300-10373-1.

- Mark, Chi-Kwan. [2004] (2004). Hong Kong and the Cold War: Anglo-American relations 1949–1957. Oxford University Press publishing. ISBN 0-19-927370-7, ISBN 978-0-19-927370-6. p 14.

- "War in China". Time. 6 March 1939. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- Cornelia Schmitz-Berning (2007). Vokabular des Nationalsozialismus (in German). Berlin: De Gruyter. p. 745. ISBN 978-3-11-019549-1.

- Rees, Laurence (2010). "What Was the Turning Point of World War II?". HISTORYNET. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- Lend-lease at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Combs, Jerald A. "Embargoes and Sanctions - World War II". Encyclopedia of American Foreign Policy. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- Rafferty, Kevin. [1990] (1990). City on the rocks: Hong Kong's uncertain future. Viking publishing. ISBN 0-670-80205-0, ISBN 978-0-670-80205-0.

- Tsang, Steve. [2007] (2007). A Modern History of Hong Kong. I.B.Tauris publishing. ISBN 1-84511-419-1, ISBN 978-1-84511-419-0. p 122, 129.

- "Hong Kong's 'Black Christmas'". China Daily. 8 December 2008. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- Bard, Solomon Bard. [2009] (2009). Light and Shade: Sketches from an Uncommon Life. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 962-209-949-1, ISBN 978-962-209-949-4. p 101, 103.

- Roland, Charles G. [2001] (2001). Long night's journey into day: prisoners of war in Hong Kong and Imperial Japan, 1941–1945. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. ISBN 0-88920-362-8, ISBN 978-0-88920-362-4. p 40, 49.

- Lim, Patricia. [2002] (2002). Discovering Hong Hong's Cultural Heritage. Central, Hong Kong: Oxford University Press. ISBN Volume One 0-19-592723-0. p 73.

- Dillon, Mike. [2008] (2008). Contemporary China: An Introduction. ISBN 0-415-34319-4, ISBN 978-0-415-34319-0. p 184.

- Jones, Carol A. G. Vagg, Jon. [2007] (2007). Criminal justice in Hong Kong. Routledge-Cavendish. ISBN 978-1-84568-038-1. p 175.

- Carroll, John Mark. [2007] (2007). A concise history of Hong Kong. ISBN 0-7425-3422-7, ISBN 978-0-7425-3422-3. p 123-125, p 129.

- "Information note IN26/02-03: The Legislative Council Building" (PDF). Legislative Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- Tse, Helen. [2008] (2008). Sweet Mandarin: The Courageous True Story of Three Generations of Chinese Women and Their Journey from East to West. Macmillan publishing. ISBN 0-312-37936-6, ISBN 978-0-312-37936-0. p 90.

- Emerson, Geoffrey Charles. [2009] (2009). Hong Kong Internment, 1942–1945: Life in the Japanese Civilian Camp at Stanley Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong studies series. HKU Press. ISBN 962-209-880-0, ISBN 978-962-209-880-0. p 83.

- Endacott, G. B. Birch, Alan. [1978] (1978). Hong Kong eclipse. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-580374-4, ISBN 978-0-19-580374-7.

- Keith Bradsher (18 April 2005). "Thousands March in Anti-Japan Protest in Hong Kong". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 February 2006. Retrieved 11 April 2006.

- Carroll 2007, p. 123.

- 半塊肩章繫隔世父子情. Apple Daily (in Chinese). 4 April 2013. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Linton, Suzannah; HKU Libraries. "WO235/993". Hong Kong’s War Crimes Trials Collection.

- Starling, Arthur E. Hong Kong Museum of Medical Sciences Society (2006). Plague, SARS and the story of medicine in Hong Kong. Hong Kong University Press, 2006. ISBN 962-209-805-3, ISBN 978-962-209-805-3. p 112, 302.

- Faure, David Faure. [1997] (1997). Society, a Documentary history of Hong Kong. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 962-209-393-0, ISBN 978-962-209-393-5. p. 209.

- Sweeting, Anthony. [2004] (2004). Education in Hong Kong, 1941 to 2001: Visions and Revisions. Hong Kong University Press publishing. ISBN 962-209-675-1, ISBN 978-962-209-675-2. pp. 88, 134.

- Higuchi, Kenichiro; Kwong, Yan Kit. [2009]. "Inflow of Japanese language into Hong Kong during the Japanese occupation period", Journal of Sugiyama Jogakuen University. Humanities. pp. 21, 22

- Higuchi, Kenichiro; Kwong, Yan Kit. [2009]."Inflow of Japanese language into Hong Kong during the Japanese occupation period", Journal of Sugiyama Jogakuen University. Humanities. p 23

- Endacott, G. B.; John M. Carroll (2005) [1962]. A biographical sketch-book of early Hong Kong. Hong Kong University Press. p. xxv. ISBN 978-962-209-742-1.

- Dew, Gwen. [2007] (2007). Prisoner of the Japs. Read books publishing. ISBN 1-4067-4681-9, ISBN 978-1-4067-4681-5. p 217.

- Gubler, Fritz. Glynn, Raewyn. [2008] (2008). Great, grand & famous hotels. Great, grand famous hotel publishing. ISBN 0-9804667-0-9, ISBN 978-0-9804667-0-6. p 285-286.

- Fu, Poshek Fu. [2003] (2003). Between Shanghai and Hong Kong: the politics of Chinese cinemas. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4518-8, ISBN 978-0-8047-4518-5. p 88.

- Wordie, Jason (12 February 2013). "Then and now: ivory tower". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- "Clippings | Furniture & Lighting | from Inspiration to Installation". Open House Hong Kong. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- unknown. "Declared Monuments in Hong Kong: Government House". Antiquities and Monuments Office, Leisure and Cultural Services Department, Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- Lee, Meiqi. [2004] (2004). Being Eurasian: memories across racial divides. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 962-209-671-9, ISBN 978-962-209-671-4. p 265.

- "Hong Kong Filmography Volume II (1942-1949) - Preface". Hong Kong Film Archive. 2014. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- Chi Man 2014, pp. 225-226.

- [2000] (2000). American Association for Chinese Studies publishing. American journal of Chinese studies, Volumes 8–9. p 141.

- Hayes, James (2006). The great difference: Hong Kong's New Territories and its people, 1898–2004. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 9789622097940.

- Chi Man, Kwong; Yiu Lun, Tsoi (2014). Eastern Fortress: A Military History of Hong Kong, 1840–1970. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. p. 227. ISBN 9789888208715.

- Bailey, Steven K. (2017). "The Bombing of Bungalow C: Friendly Fire at the Stanley Civilian Internment Camp". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong Branch. 57: 112.

- Liu, Yujing (1 February 2018). "Why does Hong Kong have so many buried wartime bombs?". Retrieved 1 January 2019.

- Roehrs, Mark D. Renzi, William A. [2004] (2004). World War II in the Pacific Edition 2. M.E. Sharpe publishing. ISBN 0-7656-0836-7, ISBN 978-0-7656-0836-9.p 246.

- Nolan, Cathal J. [2002] (2002). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of International Relations: S-Z. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-30743-1, ISBN 978-0-313-30743-0. p 1876.

- 正義的審判--中國審判侵華日軍戰犯紀實 (in Chinese). Xinhua News Agency. Retrieved 22 August 2009.

- Zhao, Li. Cohen, Warren I. [1997] (1997). Hong Kong under Chinese rule: the economic and political implications of reversion. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-62761-3, ISBN 978-0-521-62761-0.

- "William Lore | The Canadian Encyclopedia". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- Roland, Charles G. (2001). Long Night's Journey into Day: Prisoners of War in Hong Kong and Japan, 1941–1945. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. pp. xxviii, 1, 321. ISBN 0889203628.

Bibliography

Books

- Carroll, John Mark (2007). A Concise History of Hong Kong. ISBN 0-7425-3422-7, ISBN 978-0-7425-3422-3.

- Chi Man, Kwong; Yiu Lun, Tsoi (2014). Eastern Fortress: A Military History of Hong Kong, 1840–1970. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-9888208715.

- Snow, Philip (2003). The fall of Hong Kong: Britain, China and the Japanese occupation. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09352-0.

- Banham, Tony (2009). We shall suffer there: Hong Kong's defenders imprisoned, 1942–45. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-962-209-960-9.

- The History of Hong Kong by Yim Ng Sim Ha. ISBN 962-08-2231-5.

- Journey Through History: A modern Course 3 by Nelson Y.Y. Kan. ISBN 962-469-221-1.

- Mathers, Jean (1994). Twisting the Tail of the Dragon – The Story of Life in the Japanese POW Camp on the Stanley Peninsula, Hong Kong from 1941 to 1944. Sussex, England: Book Guild. ISBN 978-0-86332-966-1. Memoirs of an interned British Army wife.

Websites

- Linton, Suzannah. "Hong Kong's War Crimes Trials Collection". The University of Hong Kong. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Japanese occupation of Hong Kong. |

- Hong Kong's War Crimes Trials Collection HKU Libraries Digital Initiatives

- Fanling Babies Home – Home for War Orphaned Children – Hong Kong Orphanage

- Hong Kong Atrocities: A True Christmas Story

- Official page of Hong Kong Reparation Association

- Liberation of Hong Kong at the Wayback Machine (archived 23 July 2009)

- Diary of POW Staff Sergeant James O’Toole

- Canadians in Hong Kong

- A video clip about the occupation on YouTube

- A study of Hong Kong's garrison during the occupation

- Hong Kong Resistance: the British Army Aid Group, 1942-1945, presenting the history in an interesting way through GIS maps, images and more. Co-developed by the History Department and University Library of HKBU

.svg.png.webp)