Marcelo H. del Pilar

Marcelo Hilario del Pilar y Gatmaitán[1] (August 30, 1850 – July 4, 1896), commonly known as Marcelo H. del Pilar and also known by his pen name Plaridel,[2] was a Filipino writer, lawyer, journalist, and freemason. Del Pilar, along with José Rizal and Graciano López Jaena, became known as the leaders of the Reform Movement in Spain.[3]

Marcelo H. del Pilar | |

|---|---|

Marcelo H. del Pilar, ca. 1889 | |

| Born | Marcelo Hilario del Pilar y Gatmaitán August 30, 1850 |

| Died | July 4, 1896 (aged 45) |

| Resting place | Marcelo H. del Pilar Shrine, Bulakan, Bulacan, Philippines |

| Nationality | Filipino |

| Other names | Plaridel (pen name) |

| Alma mater | Colegio de San José University of Santo Tomas |

| Occupation | Writer, lawyer, journalist, and freemason |

| Organization | La Solidaridad |

| Spouse(s) | Marciana del Pilar (1878–1896; his death) |

| Children | 7 |

Del Pilar was born and brought up in Bulakan, Bulacan. He was suspended at the University of Santo Tomas and imprisoned in 1869 after he and the parish priest quarreled over exorbitant baptismal fees. In the 1880s, he expanded his anti-friar movement from Malolos to Manila.[4] He went to Spain in 1888 after an order of banishment was issued against him. Twelve months after his arrival in Barcelona, he succeeded López Jaena as editor of the La Solidaridad (Solidarity).[5] Publication of the newspaper stopped in 1895 due to lack of funds. Losing hope in reforms, he grew favorable of a revolution against Spain. He was on his way home in 1896 when he contracted tuberculosis in Barcelona. He later died in a public hospital and was buried in a pauper's grave.[6]

On November 30, 1997, the Technical Committee of the National Heroes Committee, created through Executive Order No. 5 by former President Fidel Ramos, recommended del Pilar along with the eight Filipino historical figures to be National Heroes.[7] The recommendations were submitted to Department of Education Secretary Ricardo T. Gloria on November 22, 1995. No action has been taken for these recommended historical figures.[7] In 2009, this issue was revisited in one of the proceedings of the 14th Congress.[8]

Biography

Early life (1850–1880)

Marcelo Hilario del Pilar y Gatmaitán was born on August 30, 1850, in Cupang (now Barangay San Nicolás), Bulacán, Bulacan.[10] He was baptized "Marcelo" on September 4, 1850.[1][11] "Hilario" was the original paternal surname of the family. The surname of Marcelo's paternal grandmother, "del Pilar", was added to comply with the naming reforms of Governor-General Narciso Clavería in 1849.[12]

Del Pilar's parents belonged to the principalía. The family owned rice and sugarcane farms, fish ponds, and an animal-powered mill.[13] His father, Julián Hilario del Pilar, was a well known Tagalog speaker in their town.[14] He was also a well known poet and writer. Don Julián served as a "three-time" gobernadorcillo of his pueblo and later held the position of oficial de mesa of the alcalde mayor.[15] Blasa Gatmaitán, del Pilar's mother, was a descendant of the noble Gatmaitáns. She was known as "Doña Blasica".[11]

The ninth of ten children, del Pilar's siblings were: Toribio (priest, deported to the Mariana Islands in 1872),[16] Fernando (father of Gregorio del Pilar),[17] Andrea, Dorotea, Estanislao, Juan, Hilaria (married to Deodato Arellano),[18] Valentín, and María. The share of the inheritance of each child was very small and del Pilar renounced his share in favor of his siblings.[2]

From an early age, del Pilar learned the violin, the piano, and the flute.[19] He received early education from his paternal uncle Alejo del Pilar.[20] He later studied Latin in the private school owned by Sr. José Flores.[21] After his education under Sr. Flores, del Pilar enrolled at the Colegio de San José,[10] where he obtained his Bachiller en Artes degree in 1860. He pursued law and Philosophy at the Universidad de Santo Tomás.[22]

In 1869, del Pilar acted as a padrino or godfather at a baptism in San Miguel, Manila.[16] Since he was not a resident of the area, he questioned the excessive baptismal fee charged by the parish priest. This angered the parish priest and as a result, the judge, Félix García Gavieres, sent del Pilar to Old Bilibid Prison (then known as Carcel y Presidio Correccional). He was released after thirty days.[23]

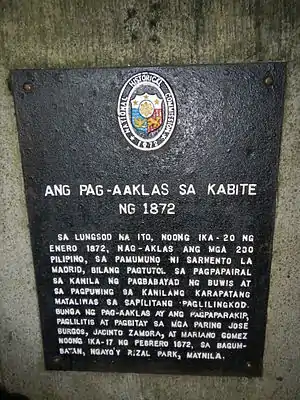

During the time of the Cavite Mutiny in 1872, del Pilar was living with a Filipino priest named Mariano Sevilla.[16] Sevilla was deported to the Mariana Islands along with del Pilar's eldest brother, Fr. Toribio Hilario del Pilar, due to allegations of being one of the organizers of the uprising.[24] The deportation of Fr. Toribio resulted in the early death of del Pilar's mother.

Out of the university, del Pilar worked as oficial de mesa in Pampanga (1874–1875) and Quiapo (1878–1879).[25] In the month of February 1878, he married his second cousin Marciana (the "Chanay/Tsanay" in his letters) in Tondo.[26] The couple had seven children, six girls and one boy: Sofía, José, María, Rosario, María Consolación, María Concepción, and Ana (Anita). Only two girls, Sofía and Anita, survived to adulthood.[27]

In 1878, del Pilar resumed his law studies at the Universidad de Santo Tomás.[28][26] He earned his licenciado en jurisprudencia (equivalent to a Bachelor of Laws) in 1881.[29] After finishing law, he worked for the Real Audiencia de Manila.[30] Although practicing law in Manila, del Pilar spent more time in his native province. There he seized every event – baptisms, funeral wakes, weddings, town fiestas, and cockfights at the cockpits – to enlighten his countrymen about the state of their native country.[31][32] He also exposed the abuses of the Spanish friars and colonial authorities.

Anti-friar activities in the Philippines (1880–1888)

Del Pilar, together with Basilio Teodoro Moran and Pascual H. Poblete, founded the short-lived Diariong Tagalog (Tagalog Newspaper) on June 1, 1882.[16] Diariong Tagalog was the first bilingual newspaper in the Philippines and was financed by the wealthy Spanish liberal Francisco Calvo y Muñoz.[33] Del Pilar became the editor of the Tagalog section.[34] José Rizal's essay, El Amor Patrio, was featured in the Diariong Tagalog on August 20, 1882. Del Pilar translated it into Tagalog language, Ang Pagibig sa Tinubúang Lupà (Love of Country).[35]

Malolos became the center of del Pilar's anti-friar movement. The first success of the movement was in 1885, when the liberal Manuel Crisóstomo was elected gobernadorcillo by the citizens of Malolos. Shortly after this victorious event, del Pilar, together with the cabezas de barangay of Malolos, clashed with the town's friar curate on the list of taxpayers.[36] The friar curate wanted to bloat the tax lists, a move meant for the parish's financial gain.[37]

In October 1887, during an upcoming fiesta in Binondo, a conflict occurred between the natives, Chinese, and Chinese mestizos. The gobernadorcillo de naturales (gobernadorcillo of the natives) of Binondo, Timoteo Lanuza, requested Fr. José Hevia de Campomanes, the friar curate of Binondo Church, to prioritize the natives over the Chinese in the fiesta.[38] Fr. Hevia, who sided with the Chinese and Chinese mestizos, rejected Lanuza's request and decided not to attend the celebration. Most of the attendees of the fiesta were the gobernadorcillos of Manila and the natives. A few days after the celebration, Fr. Hevia was removed as friar curate of Binondo by the liberal governor-general Emilio Terrero. The organizer of the fiesta, Juan Zulueta, was a disciple of del Pilar.[39]

On October 18, 1887, Benigno Quiroga y López Ballesteros, the Director General of Civil Administration in Manila, issued an executive order prohibiting the exposition of dead bodies of cholera victims in the churches.[40] Crisóstomo, the gobernadorcillo of Malolos at that time, proclaimed Quiroga's decree by means of a parade led by a brass band. Friar Felipe García, the friar-curate of Malolos, aggravated the authorities by parading the body of the servant of Don Eugenio Delgado. Upon the advice of del Pilar, Crisóstomo addressed the problem to the Spanish governor of Bulacan, Manuel Gómez Florio. Gómez Florio ordered the arrest of the friar curate.[41]

On January 21, 1888, del Pilar worked for the establishment of a school of "Arts, Trades, and Agriculture" by drafting of a memorial to the gobernador civil of Bulacan.[42] This was signed by the gobernadorcillos, ex-gobernadorcillos, leading citizens, proprietors, industrialists, professors, and lawyers of the province.

On March 1, 1888, the residents of the districts of Manila and the nearby provinces, led by Doroteo Cortés and José A. Ramos, marched to the office of the civil governor of Manila, José Centeno García.[19] They presented a manifesto addressed to the Queen Regent.[43] This manifesto, entitled "Viva España! Viva el Rey! Viva el Ejército! Fuera los Frailes!" (Long live Spain! Long live the King! Long live the Army! Throw the friars out!), was written by del Pilar.[44][37] The manifesto enumerated the abuses and crimes of the friars and demanded their expulsion from the Philippines including Manila Archbishop Pedro P. Payo. A week after the demonstration, Centeno resigned and left for Spain. Governor-general Terrero's term also ended the following month. Terrero was succeeded by acting governor-general Antonio Moltó.[45]

.jpg.webp)

Fr. José Rodríguez, an Augustinian priest, authored a pamphlet entitled ¡Caiñgat Cayó!: Sa mañga masasamang libro,t, casulatan (Beware!: of bad books and writings, 1888). The friar warned the Filipinos that in reading Rizal's Noli Me Tángere (Touch Me Not) they commit "mortal sin". On August 3 of the same year, del Pilar wrote Caiigat Cayó (Be as Slippery as an Eel) under the pen name Dolores Manapat. It was a reply to Rodríguez's ¡Caiñgat Cayó!.[46]

Valeriano Weyler succeeded Moltó as the governor-general of the Philippines. Investigations were escalated during Weyler's term. Gómez Florio, the Spanish governor of Bulacan and del Pilar's friend, was removed from his position. An arrest warrant was issued against del Pilar, accusing him of being a filibustero and heretic. Upon the advice of his friends and relatives, del Pilar left Manila for Spain on October 28, 1888.[47] The night before he left the country, del Pilar stayed at the house of his fellow Bulaqueño, Pedro Serrano y Lactao. Together with Rafael Enriquez, they wrote the Dasalan at Tocsohan (Prayers and Mockeries), a mock-prayer book satirizing the Spanish friars.[48][49] They also wrote the Pasióng Dapat Ipag-alab nang Puso nang Tauong Babasa (Passion That Should Inflame the Heart of the Reader).[50]

Del Pilar was also able to organize the Caja de Jesús, María y José, the objective of which was to continue propaganda and provide education to indigent children.[51] He managed the organization with the assistance of Mariano Ponce, Gregorio Santillán, Mariano Crisóstomo, Lactao, and José Gatmaitán. Caja de Jesús, María y José was later terminated and replaced by Comité de Propaganda (Committee of Propaganda) in Manila.

Propaganda movement in Spain (1888–1895)

Del Pilar arrived in Barcelona on January 1, 1889.[52] He headed the political section of the Asociación Hispano-Filipina de Madrid (Hispanic Filipino Association of Madrid).[53] On February 17, 1889, del Pilar wrote a letter to Rizal, praising the young women of Malolos for their bravery. These 20 young women asked the permission of Governor-General Weyler to allow them to open a night school where they could learn to read and write Spanish. With Weyler's approval and over the objections of Friar Felipe García, the night school opened in the early 1889. Del Pilar considered this incident as a victory to the anti-friar movement. Upon his request, Rizal wrote his famous letter to the women of Malolos, Sa Mga Kababayang Dalaga Sa Malolos (To the Young Women of Malolos), on February 22, 1889.[51][54]

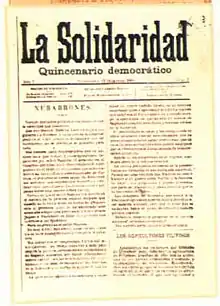

On December 15, 1889, del Pilar succeeded Graciano López Jaena as editor of the La Solidaridad.[5] Under his editorship, the aims of the newspaper expanded. Using propaganda, it pursued the desires for: assimilation of the Philippines as a province of Spain; removal of the friars and the secularization of the parishes; freedom of assembly and speech; equality before the law; and Philippine representation in the Cortes, the legislature of Spain.[55][56]

In 1890, a rivalry developed between del Pilar and Rizal. This was mainly due to the difference between del Pilar's editorial policy and Rizal's political beliefs.[57] On January 1, 1891, about 90 Filipinos gathered in Madrid. They agreed that a Responsable (leader) be elected.[58] Camps were drawn into two, the Pilaristas and the Rizalistas. The first voting for the Responsable started on the first week of February 1891. Rizal won the first two elections but the votes counted for him did not reach the needed two thirds vote fraction. After Mariano Ponce pleaded to the Pilaristas, Rizal was elected Responsable. Rizal, knowing the Pilaristas did not like his political beliefs, respectfully declined the position and transferred it to del Pilar. He then packed up his bags and boarded a train leaving for Biarritz, France.[59] Inactive in the Reform Movement, Rizal ceased his contribution of articles on La Solidaridad.

After the incident, del Pilar wrote a letter of apology to Rizal.[57] Rizal responded and said that he stopped writing for La Solidaridad for reasons: first, he needed time to work on his second novel El Filibusterismo (The Reign of Greed);[60] second, he wanted other Filipinos in Spain to work also; and lastly, he could not lead an organization without solidarity in work.

After years of publication from 1889 to 1895, funding of the La Solidaridad became scarce. Comité de Propaganda's contribution to the newspaper stopped and del Pilar funded the newspaper almost on his own. On November 15, 1895, La Solidaridad ceased publication, with 7 volumes and 160 issues.[61] In del Pilar's farewell editorial, he said :

We are persuaded that no sacrifices are too little to win the rights and the liberty of a nation that is oppressed by slavery.[62]

Later years, illness, and death (1895–1896)

Del Pilar's last years in Spain saw his descent into extreme poverty. He often missed his meals and during winter, he kept himself warm by smoking discarded cigarette butts he picked up in the streets. Suffering from tuberculosis, del Pilar decided to return to the Philippines. His illness worsened that he had to cancel his journey.[63] He was taken to the Hospital de la Santa Cruz in Barcelona. Del Pilar died there on July 4, 1896, a few days before the Cry of Pugad Lawin.[64] He was buried the following day in a borrowed grave at the Cementerio del Sub-Oeste (Southwest Cemetery). Before dying, del Pilar retracted from Masonry and received the sacraments of the church.[65]

Reactions after death

News of his death reached the Philippines. La Politica de España en Filipinas, the publication of the Spanish priests, paid respect to him:

Del Pilar, the Tagalog who, as publicist, inspired us with the greatest esteem. As a reformist, he is doubtless the greatest produced by the Tagalog race.[66]

Ramón Blanco y Erenas, the Governor-General of the Philippines at that time, eulogized del Pilar as:

The most intelligent leader, the real soul of the separatists, very superior to Rizal.[67][68]

Return of del Pilar's remains (1920) and final interment (1984)

Del Pilar's remains were returned to the Philippines on December 3, 1920 and was buried initially at the Manila North Cemetery.[69] It was later transferred to his birthplace in Bulakan, Bulacan on August 30, 1984.[70]

Historical controversy

Mastermind of the Katipunan

Some historians and scholars believed that del Pilar was the true mastermind of the Katipunan.[71][72] According to the historian Renato Constantino, the ordinance of the Katipunan were submitted by Andrés Bonifacio to del Pilar for validation.[73] Bonifacio used the letters he received from del Pilar to recruit more Katipuneros. Kalayaan (Liberty), the official newspaper of the Katipunan, carried the pseudonym of del Pilar, Plaridel, as editor-in-chief.[74] A copy of the letters of del Pilar was also given by Bonifacio to Deodato Arellano, del Pilar's brother-in-law and the first president of Katipunan. According to León María Guerrero, del Pilar's letters were regarded by Bonifacio as important documents of the Philippine Revolution and guides for Katipunan's activities.[37]

Historical remembrance

"Father of Philippine Journalism"

For his 150 essays and 66 editorials mostly published in La Solidaridad and various anti-friar pamphlets, del Pilar is widely regarded as the "Father of Philippine Journalism."[75]

Samahang Plaridel, an organization of veteran journalists and communicators, was founded in October 2003 to honor del Pilar's ideals. It also promotes mutual help, cooperation, and understanding among Filipino journalists.[76]

"Father of Philippine Masonry"

Del Pilar was initiated into Freemasonry in 1889.[77] He served as venerable master of the famous Solidaridad lodge of Madrid. He became a close friend of Miguel Morayta y Sagrario, a professor at the Universidad Central de Madrid and Grand Master of Masons of the Grande Oriente Español.[78]

Del Pilar was directly responsible for the establishment of the first national organization of Filipino Masons, the Gran Consejo Regional de Filipinas, in 1893. With this, he earned the recognition as the "Father of Philippine Masonry." The Masonic Grand Lodge of the Philippines is named Plaridel Masonic Temple.

Legacy and portrayals

- Marcelo H. del Pilar was featured on obverse of the Philippine fifty centavo coin in 1967–72 and again in 1983–94.[79]

- Portrayed by Dennis Marasigan in the Filipino film José Rizal (1998).[80]

- Portrayed by Mike Liwag in the TV series Ilustrado (2014).[81]

- The building which houses the College of Mass Communication in UP Diliman is named Plaridel Hall in his memory.

Notable works

Published during del Pilar's lifetime

- La Solídaridad ("Published")

- Viva España! Viva el Rey! Viva el Ejército! Fuera los Frailes! (Long live Spain! Long live the King! Long live the Army! Throw the friars out!, 1888)[44][37]

- Caiigat Cayó (Be as Slippery as an Eel, 1888)[46]

- Dasalan at Tocsohan (Prayers and Mockeries, 1888) [48][49]

- Ang Cadaquilaan nang Dios (The Greatness of God, 1888)[82]

- La Soberanía Monacal en Filipinas (Monastic Supremacy in the Philippines, 1888)[83]

- Pasióng Dapat Ipag-alab nang Puso nang Tauong Babasa (Passion That Should Inflame the Heart of the Reader, 1888)[50]

- La Frailocracía Filipina (Friarocracy in the Philippines, 1889)[84]

- Sagót ng España sa Hibíc ng Filipinas (Spain's Reply to the Cry of the Philippines, 1889)[85]

- Ministerio dela República Filipina (Ministry of the Philippine Republic)[86]

- La Patria (The Fatherland)[86]

Published posthumously

- Dupluhan... Dalits... Bugtongs (A Poetical Contest in Narrative Sequence, Psalms, Riddles, 1907)[87]

Unpublished work

- Sa Bumabasang Kababayan[87]

See also

References

- "Film # 007773626 Image Film # 007773626; ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSMJ-S934-4 — FamilySearch.org". Retrieved May 19, 2016.

- Kahayon 1989, p. 52.

- Guerrero, A. M. Bulacañana: A Heritage of Artistic Excellence. Provincial Youth, Sports, Employment, Art and Culture Office (PYSEACO), Provincial Government of Bulacan. pp. 10–11.

- Reyes 2008, p. 129.

- Keat 2004, p. 756

- Valeriano, A. B. "Marcelo H. del Pilar: Ang Kanyang Buhay, Diwa at Panulat". Samahang Pangkalinangan ng Bulakan, Bulacan.

- "Selection and Proclamation of National Heroes and Laws Honoring Filipino Historical Figures". National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Archived from the original on April 18, 2015. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- "Congressional Record: Plenary Proceedings of the 14th Congress, Third Regular Session" (PDF). Philippine House of Representatives. August 3, 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 18, 2013. Retrieved May 11, 2015.

- Santos 2001, p. 48.

- Schumacher 1997, p. 105.

- Villarroel 1997, p. 9.

- Ocampo, Ambeth R. (August 28, 2012), "Looking Back: Did M.H. del Pilar dream in color?", Philippine Daily Inquirer

- Reyes 2008, p. 261.

- Mojares 1983, p. 131.

- Zapanta 1967, p. 58.

- Schumacher 1997, p. 106.

- Kalaw 1974, p. 3.

- Kalaw 1974, p. 5.

- Reyes 2008, p. 130.

- Zapanta 1967, p. 63.

- Zapanta 1967, p. 59.

- Reyes 2008, p. 262.

- Reyes 2008, p. 118.

- Villarroel 1997, p. 10.

- Batungbacal 1956, p. 27.

- Villarroel 1997, p. 11.

- Zapanta 1967, p. 64.

- Zapanta 1967, p. 70.

- Nepomuceno-Van Heugten, Maria Lina. "Edukasyon ng Bayani: Mga Impluwensya ng Edukasyong Natamo sa Kaisipang Rebolusyonaryo" (PDF). University of the Philippines Diliman Journals Online. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- Villarroel 1997, p. 41.

- Constantino 1975, p. 149.

- "Marcelo H. del Pilar". oocities.org. Retrieved May 20, 2013.

- Zapanta 1967, p. 76.

- Villarroel 1997, p. 42.

- Reyes 2008, p. 150.

- Zapanta 1967, p. 84.

- Guerrero, Leon Ma. (December 13, 1952). "Del Pilar". The Philippines Free Press Online. Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- Fajardo 1998, p. 48.

- Batungbacal 1956, p. 29.

- Zapanta 1967, p. 86.

- Zapanta 1967, p. 87.

- Zapanta 1967, p. 62.

- Reyno, Ma. Cielito G. (September 6, 2012). "The Petition of March 1888". nhcp.gov.ph. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- Zapanta 1967, p. 89.

- "Masonry and the Philippine Revolution". mastermason.com. Retrieved June 16, 2013.

- Schumacher 1997, p. 121.

- Schumacher 1997, p. 122.

- Schumacher 1997, p. 125.

- Reyes 2008, p. 131.

- Schumacher 1997, p. 126.

- Zapanta 1967, p. 83.

- Zapanta 1967, p. 94.

- Zapanta 1967, p. 95.

- "Rizal's Letter: To The Young Women of Malolos (Analysis)". wn.com.

- del Pilar, Marcelo H. (April 25, 1889). "The aspirations of the Filipinos". Barcelona, Spain: La Solidaridad. Archived from the original on July 13, 2010. Retrieved September 11, 2011.

- "Liberalism in the Philippines – The Revolution of 1898 : The Main Facts". sspxasia.com. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

- Mañebog, Jensen DG. (September 1, 2013). "The 'Love-and-Hate' Relationship of Jose Rizal And Marcelo del Pilar". ourhappyschool.com. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- Corpuz 2007, p. 208.

- Corpuz 2007, p. 210.

- "The Reign of Greed by José Rizal". Retrieved October 12, 2020.

- "Today in Philippine History, November 15, 1895, the La Solidaridad stopped publication". kahimyang.com. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- http://www.knightsofrizal.be/la_solidaridad/default.html

- Zapanta 1967, p. 174.

- Schumacher 1997, p. 293.

- Maximiano, Jose Mario Bautista (June 10, 2020), "Did Rizal, López-Jaena, Del Pilar go to Heaven?", Philippine Daily Inquirer, retrieved October 12, 2020

- http://www.geocities.ws/melst/page%207.html

- Zapanta 1967, p. 171.

- http://kahimyang.info/kauswagan/articles/554/today-in-philippine-history-august-30-1850-marcelo-h-del-pilar-was-born-in-cupang-bulacan-bulacan

- Ocampo, Ambeth R. (July 30, 2008), "Looking Back: The search for Plaridel's remains", Philippine Daily Inquirer, archived from the original on July 29, 2013

- Lopez, Ron B. (June 11, 2013). "An afternoon at Plaridel's house". mb.com.ph. Archived from the original on June 15, 2013. Retrieved June 15, 2013.

- Gamos, Emil G. (August 29, 2014). "New studies reveal that Del Pilar was the "mastermind" of the "Katipunan"". manilanewsonline.com. Archived from the original on February 11, 2015. Retrieved February 11, 2015.

- Richardson, Jim (August 2014). "Marcelo H. del Pilar and the Katipunan – sources of confusion" (PDF). wordpress.com. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- Constantino 1975, p. 163.

- Arturo Ma. Misa, Del Pilar and the Katipunan (Manila: The Philippines Free Press, 1959).

- Balabo, Dino (August 30, 2011). "Bulacan marks Marcelo H. del Pilar Day today". philstar.com. Retrieved February 11, 2015.

- Roces, Alejandro R. (September 4, 2008). "Plaridel – a shining example for our journalists". philstar.com. Retrieved February 11, 2015.

- "Famous Filipino Mason – Marcelo H. del Pilar". Most Worshipful Grand Lodge of the Philippines. Retrieved January 12, 2010.

- http://philippines-islands-lemuria.blogspot.com/2011/01/12-january.html

- "50 Sentimos, Philippines". en.numista.com. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- List of the José Rizal Film Cast

- "Ilustrado". Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- Ramos 1984, p. 86.

- Steinberg 2000, p. 245.

- Schumacher 1997, p. 119.

- Abdula, Allan Yasser (May 4, 2008). "Expat in the City: Isang Pagkukuro sa "Sagot Ng Espanya sa Hibik Ng Pilipinas"". aabdula.blogspot.com. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- Dery 1999, p. 26.

- Mojares 1983, p. 132.

Bibliography

- Batungbacal, José (1956). Great Architects of Filipino Nationality. Manila: University Publishing Company. OCLC 3515670.

- Constantino, Renato (1975). The Philippines: A Past Revisited. Quezon City: Tala Publishing Services. ISBN 971-8958-00-2.

- Corpuz, Onofre D. (2007). The Roots of the Filipino Nation, Volume 2. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press. ISBN 978-971-542-461-5.

- Dery, Luis Camara (1999). Alay sa Inang Bayan: Panibagong Pagbibigay Kahulugan sa Kasaysayan ng Himagsikan ng 1896. Ermita, Manila: National Historical Institute. ISBN 978-971-538-155-0.

- Fajardo, Reynold S. (1998). The Brethren: Masons in the Struggle for Philippine Independence, Volume 1. Manila: E.L. Locsin and the Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of the Philippines. ISBN 971-91946-1-8.

- Kahayon, Alicia H. (1989). Philippine Literature: Choice Selections from a Historical Perspective. Manila: National Book Store. ISBN 971-084-378-8.

- Kalaw, Teodoro M. (1974). An Acceptable Holocaust: Life and Death of a Boy-General. Manila: National Historical Commission. OCLC 1659785.

- Keat, Gin Ooi (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-57607-770-5.

- Mojares, Resil B. (1983). Origins and Rise of the Filipino Novel: A Generic Study of the Novel Until 1940. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press. ISBN 971-105-001-3.

- Ramos, Maria S. (1984). Panitikang Pilipino. Quezon City: Katha Publishing Company. ISBN 971-150-051-5.

- Reyes, Raquel A. G. (2008). Love, Passion, and Patriotism: Sexuality and the Philippine Propaganda Movement, 1882 – 1892. Singapore: NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-356-5.

- Santos, Mariano T. (2001). Aklat ng Bayang Bulacan. Bulacan: Lathalaang Plaridel. ISBN 971-92439-0-2.

- Schumacher, John N. (1997). The Propaganda Movement, 1880-1895: The Creation of a Filipino Consciousness, the Making of the Revolution. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 971-550-209-1.

- Steinberg, David J. (2000). The Philippines: A Singular and a Plural Place. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-3755-0.

- Villarroel, Fidel (1997). Marcelo H. del Pilar at the University of Santo Tomas. Manila: University of Santo Tomas Publishing House. ISBN 971-506-070-6.

- Zapanta, Lea S. (1967). The Political Ideas of Marcelo H. del Pilar. Quezon City: University of the Philippines. OCLC 48934308.

Further reading

- Antonio, Teo T. (2000). Piping-dilat. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press. ISBN 978-9715422512.

- Cortez, King M. (2016). Plaridel: Dungan ng Katipunan. Malolos: Center for Bulacan Studies, Bulacan State University. ISBN 978-971-0572-86-1.

- Gatmaitan, Magno S. (1966). Marcelo H. del Pilar, 1850-1896: A Documented Biography, with Tagalog, English and Spanish Versions. Quezon City: Muñoz Press. OCLC 33251139.

- Pilar, Marcelo H. del (1955). Epistolario de Marcelo H. del Pilar, Volume 1. Manila: Imprenta del Gobierno. OCLC 5390874.

- Pilar, Marcelo H. del (1970). Escritos de Marcelo H. del Pilar, Volumes 1–2. Manila: Biblioteca Nacional. OCLC 8783472.

- Pilar, Marcelo H. del (2006). Letters of Marcelo H. del Pilar: A Collection of Letters of Marcelo H. del Pilar. Manila: National Historical Institute. ISBN 971-538-194-4.

- Villarroel, Fidel (1997). Marcelo H. Del Pilar, His Religious Conversions. Manila: University of Santo Tomas Publishing House. ISBN 978-9715060714.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Epifanio de los Santos, Marcelo H. del Pilar (Part 1), The Philippine Review (Revista Filipina) [Vol. 1, no. 5]

- Epifanio de los Santos, Marcelo H. del Pilar (Part 1, continuation), The Philippine Review (Revista Filipina) [Vol. 1, no. 5]

- Epifanio de los Santos, Marcelo H. del Pilar (Part 2), The Philippine Review (Revista Filipina) [Vol. 1, no. 5]

- Epifanio de los Santos, Marcelo H. del Pilar (Part 2, continuation), The Philippine Review (Revista Filipina) [Vol. 1, no. 5]

- Epifanio de los Santos, Marcelo H. del Pilar (Part 3), The Philippine Review (Revista Filipina) [Vol. 1, no. 5]

- BAYANIart: Marcelo del Pilar Biography

- PLARIDEL: Hindi lang propagandista, siya ang utak ng Katipunan

- Bulacan, Philippines: Tourism: Marcelo H. del Pilar Shrine

- ¡Caiñgat Cayo!

- Philippine History – Plaridel

- The Philippine Revolution: La Solidaridad