Baybayin

Baybayin (Tagalog pronunciation: [bai̯ˈba:jɪn], pre-kudlit: , virama-krus-kudlit: , virama-pamudpod: ; also incorrectly known as alibata) is a pre-Hispanic Philippine script. It is an alphasyllabary belonging to the family of the Brahmic scripts. It was widely used in Luzon and other parts of the Philippines prior to and during the 16th and 17th centuries before being supplanted by the Latin alphabet during the period of Spanish colonization. The characters are in the Unicode Basic Multilingual Plane (BMP), and were first proposed for encoding in 1998 by Michael Everson together with three other known indigenous scripts of the Philippines.[4] In the 19th and 20th centuries, baybayin survived and evolved into the forms of Tagbanwa script of Palawan, Hanuno'o and Buhid scripts of Mindoro, and was used to create the modern Kulitan script of the Kapampangan, and Ibalnan script of the Palaw'an tribe.

| Baybayin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Languages | Tagalog, Sambali, Ilocano, Kapampangan, Bikolano, Pangasinense, Bisayan languages[1] |

Time period | 14th century (or older)[2] - 18th century (revived in modern times)[3] |

Parent systems | |

Print basis | Writing direction (different variants of baybayin): left-to-right, top-to-bottom bottom-to-top, left-to-right top-to-bottom, right-to-left |

Child systems | • Buhid script • Hanunuo script • Kulitan Script • Palaw'an script • Tagbanwa script |

Sister systems | In Indonesia: • Balinese (Aksara Bali, Hanacaraka) • Batak (Surat Batak, Surat na sampulu sia) • Javanese (Aksara Jawa, Dęntawyanjana) • Lontara (Mandar) • Sundanese (Aksara Sunda) • Rencong (Rentjong) • Rejang (Redjang, Surat Ulu) |

| Direction | left-to-right |

| ISO 15924 | Tglg, 370: Tagalog (Baybayin, Alibata) |

Unicode alias | Tagalog |

| U+1700–U+171F | |

| Brahmic scripts |

|---|

| The Brahmic script and its descendants |

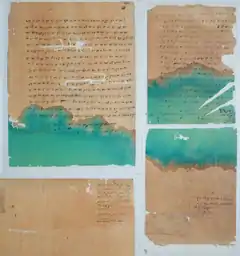

The Archives of the University of Santo Tomas in Manila, one of the largest archives in the Philippines, currently possesses the world's biggest collection of ancient writings in baybayin.[5][6][7][8] The chambers which house the writings are part of a tentative nomination to UNESCO World Heritage List that is still being deliberated on, along with the entire campus of the University of Santo Tomas.

Despite being primarily a historic script, the baybayin script has seen some revival in the modern Philippines. It is often used in the insignia of government agencies, and books are frequently published either partially, or fully, in baybayin. Bills to require its use in certain cases and instruction in schools have been repeatedly considered by the Congress of the Philippines.[9]

Terminology

The term baybayín means "to write" or "to spell (syllabize)" in Tagalog. The entry for "ABC's" (i.e., the alphabet) in San Buenaventura's Vocabulary of the Tagalog language (1613) was translated as baibayin ("...de baybay, que es deletrear...", transl. "from baybay, meaning, to spell").

The word baybayin is also occasionally used to refer to the other indigenous writing systems of the Philippines, such as the Buhid script, Hanunó'o script, Tagbanwa script, Kulitan script, among others. Cultural organizations such as Sanghabi and the Heritage Conservation Society recommend that the collection of distinct scripts used by various indigenous groups in the Philippines, including baybayin, iniskaya, kirim jawi, and batang-arab be called suyat, which is a neutral collective noun for referring to any pre-Hispanic Philippine script.[11]

Baybayin is occasionally referred to as alibata,[12][13] a neologism coined by Paul Rodríguez Verzosa in 1914, after the first three letters of the Arabic script (ʾalif, bāʾ, tāʾ; the f in ʾalif having been dropped for euphony's sake), presumably under the erroneous assumption that baybayin was derived from it.[14] Most modern scholars reject the use of the word alibata as incorrect.[14][15]

In modern times, baybayin has been called badlit, kudlit-kabadlit by the Visayans, kurditan, kur-itan by the Ilocanos, and basahan by the Bicolanos.[15]

Origins

The origins of baybayin are disputed and multiple theories exist as to its origin.

Influence of Greater India

Historically Southeast Asia was under the influence of Ancient India, where numerous Indianized principalities and empires flourished for several centuries in Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Philippines, Cambodia and Vietnam. The influence of Indian culture into these areas was given the term Indianization.[16] French archaeologist, George Coedes, defined it as the expansion of an organized culture that was framed upon Indian originations of royalty, Hinduism and Buddhism and the Sanskrit language.[17] This can be seen in the Indianization of Southeast Asia, Hinduism in Southeast Asia and the spread of Buddhism in Southeast Asia. Indian honorifics also influenced the Malay, Thai, Filipino and Indonesian honorifics.[18] Examples of these include Raja, Rani, Maharlika, Datu, etc. which were transmitted from Indian culture to Philippines via Malays and the Srivijaya empire. Indian Hindu colonists played a key role as professionals, traders, priests and warriors.[19][20][21][22] Inscriptions have proved that the earliest Indian colonists who settled in Champa and the Malay archipelago, came from the Pallava dynasty, as they brought with them their Pallava script. The earliest inscriptions in Java exactly match the Pallava script.[19] In the first stage of adoption of Indian scripts, inscriptions were made locally in Indian languages. In the second stage, the scripts were used to write the local Southeast Asian languages. In the third stage, local varieties of the scripts were developed. By the 8th century, the scripts had diverged and separated into regional scripts.[23]

Isaac Taylor sought to show that baybayin was introduced into the Philippines from the Coast of Bengal sometime before the 8th century. In attempting to show such a relationship, Taylor presented graphic representations of Kistna and Assam letters like g, k, ng, t, m, h, and u, which resemble the same letters in baybayin. Fletcher Gardner argued that the Philippine scripts have "very great similarity" with the Brahmi script.,[24] which was supported by T. H. Pardo de Tavera. According to Christopher Miller, evidence seems strong for baybayin to be ultimately of Gujarati origin, however Philippine and Gujarati languages have final consonants, so it is unlikely that their indication would have been dropped had baybayin been based directly on a Gujarati model.[25]

South Sulawesi scripts

David Diringer, accepting the view that the scripts of the Malay archipelago originate in India, writes that the South Sulawesi scripts derive from the Kawi script, probably through the medium of the Batak script of Sumatra. The Philippine scripts, according to Diringer, were possibly brought to the Philippines through the Buginese characters in Sulawesi.[26] According to Scott, baybayin's immediate ancestor was very likely a South Sulawesi script, probably Old Makassar or a close ancestor.[27] This is because of the lack of final consonants or vowel canceller markers in baybayin. South Sulawesi languages have a restricted inventory of syllable-final consonants and do not represent them in the Bugis and Makassar scripts. The most likely explanation for the absence of final consonant markers in baybayin is therefore that its direct ancestor was a South Sulawesi script. Sulawesi lies directly to the south of the Philippines and there is evidence of trade routes between the two. Baybayin must therefore have been developed in the Philippines in the fifteenth century CE as the Bugis-Makassar script was developed in South Sulawesi no earlier than 1400 CE.[28]

Kawi script

The Kawi script originated in Java, descending from the Pallava script,[29] and was used across much of Maritime Southeast Asia. The Laguna Copperplate Inscription is the earliest known written document found in the Philippines. It is a legal document with the inscribed date of Saka era 822, corresponding to April 21, 900 AD. It was written in the Kawi script in a variety of Old Malay containing numerous loanwords from Sanskrit and a few non-Malay vocabulary elements whose origin is ambiguous between Old Javanese and Old Tagalog. A second example of Kawi script can be seen on the Butuan Ivory Seal, found in the 1970s and dated between the 9th and 12th century. It is an ancient seal made of ivory that was found in an archaeological site in Butuan. The seal has been declared as a National Cultural Treasure. The seal is inscribed with the word "Butwan" in stylized Kawi. The ivory seal is now housed at the National Museum of the Philippines.[30] One hypothesis therefore reasons that, since Kawi is the earliest attestation of writing in the Philippines, then baybayin may have descended from Kawi.

Cham script

Baybayin could have been introduced to the Philippines by maritime connections with the Champa Kingdom. Geoff Wade has argued that the baybayin characters "ga", "nga", "pa", "ma", "ya" and "sa" display characteristics that can be best explained by linking them to the Cham script, rather than other Indic abugidas. Baybayin seems to be more related to southeast Asian scripts than to Kawi script. Wade argues that the Laguna Copperplate Inscription is not definitive proof for a Kawi origin of baybayin, as the inscription displays final consonants, which baybayin does not.[31]

History

From the material that is available, it is clear that baybayin was used in Luzon, Palawan, Mindoro, Pangasinan, Ilocos, Panay, Leyte and Iloilo, but there is no proof supporting that baybayin reached Mindanao. It seems clear that the Luzon and Palawan varieties have started to develop in different ways in the 1500s, way before the Spaniards conquered what we know today as the Philippines. This puts Luzon and Palawan as the oldest regions where baybayin was and is used. It is also notable that the script used in Pampanga had already developed special shapes for four letters by the early 1600s, different from the ones used elsewhere. There were three somewhat distinct varieties of baybayin in the late 1500s and 1600s, though they could not be described as three different scripts any more than the different styles of Latin script across medieval or modern Europe with their slightly different sets of letters and spelling systems.[5][1]

| Script | Region | Sample |

|---|---|---|

| Baybayin | Tagalog region | |

| Sambal variety | Zambales |  |

| Ilocano variety, Ilocano: "Kur-itan" | Ilocos |  |

| Bicolano variety, Bicolano: "Iskriturang Basahan" | Bicol Region |  |

| Pangasinense variety | Pangasinan | |

| Visayan variety, Visayan: "Badlit" | Visayas |  |

| Kapampangan variety, Kapampangan: "Kulitan" | Central Luzon |  |

Early history

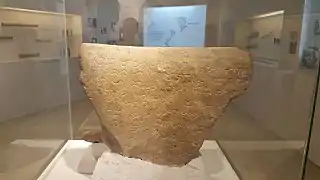

An earthenware burial jar, called the "Calatagan Pot," found in Batangas is inscribed with characters strikingly similar to baybayin, and is claimed to have been inscribed ca. 1300 AD. However, its authenticity has not yet been proven.[32][33]

Although one of Ferdinand Magellan's shipmates, Antonio Pigafetta, wrote that the people of the Visayas were not literate in 1521, the baybayin had already arrived there by 1567 when Miguel López de Legazpi reported from Cebu that, "They [the Visayans] have their letters and characters like those of the Malays, from whom they learned them; they write them on bamboo bark and palm leaves with a pointed tool, but never is any ancient writing found among them nor word of their origin and arrival in these islands, their customs and rites being preserved by traditions handed down from father to son without any other record."[34] A century later, in 1668 Francisco Alcina wrote: "The characters of these natives [Visayans], or, better said, those that have been in use for a few years in these parts, an art which was communicated to them from the Tagalogs, and the latter learned it from the Borneans who came from the great island of Borneo to Manila, with whom they have considerable traffic... From these Borneans the Tagalogs learned their characters, and from them the Visayans, so they call them Moro characters or letters because the Moros taught them... [the Visayans] learned [the Moros'] letters, which many use today, and the women much more than the men, which they write and read more readily than the latter."[14] Francisco de Santa Inés explained in 1676 why writing baybayin was more common among women, as "they do not have any other way to while away the time, for it is not customary for little girls to go to school as boys do, they make better use of their characters than men, and they use them in things of devotion, and in other things that are not of devotion."[35]

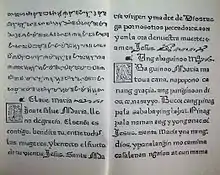

The earliest printed book in a Philippine language, featuring both Tagalog in baybayin and transliterated into Latin script, is the 1593 Doctrina Christiana en Lengua Española y Tagala. The Tagalog text was based mainly on a manuscript written by Fr. Juan de Placencia. Friars Domingo de Nieva and Juan de San Pedro Martyr supervised the preparation and printing of the book, which was carried out by an unnamed Chinese artisan. This is the earliest example of baybayin that exists today and it is the only example from the 1500s. There is also a series of legal documents containing baybayin, preserved in Spanish and Philippine archives that span more than a century: the three oldest, all in the Archivo General de Índias in Seville, are from 1591 and 1599.[36][1]

Baybayin was noted by the Spanish priest Pedro Chirino in 1604 and Antonio de Morga in 1609 to be known by most Filipinos, and was generally used for personal writings, poetry, etc. However, according to William Henry Scott, there were some datus from the 1590s who could not sign affidavits or oaths, and witnesses who could not sign land deeds in the 1620s.[37]

In 1620, Libro a naisurátan amin ti bagás ti Doctrina Cristiana was written by Fr. Francisco Lopez, an Ilokano Doctrina the first Ilokano baybayin, based on the catechism written by Cardinal Belarmine.[38] This is an important moment in the history of baybayin, because the krus-kudlít was introduced for the first time, which allowed writing final consonants. He commented the following on his decision:[14] "The reason for putting the text of the Doctrina in Tagalog type... has been to begin the correction of the said Tagalog script, which, as it is, is so defective and confused (because of not having any method until now for expressing final consonants - I mean, those without vowels) that the most learned reader has to stop and ponder over many words to decide on the pronunciation which the writer intended." This krus-kudlit, or virama kudlit, did not catch on among baybayin users, however. Native baybayin experts were consulted about the new invention and were asked to adopt it and use it in all their writings. After praising the invention and showing gratitude for it, they decided that it could not be accepted into their writing because "It went against the intrinsic properties and nature that God had given their writing and that to use it was tantamount to destroy with one blow all the Syntax, Prosody and Orthography of their Tagalog language."[40]

In 1703, baybayin was reported to still be used in the Comintan (Batangas and Laguna) and other areas of the Philippines.[41]

Among the earliest literature on the orthography of Visayan languages were those of Jesuit priest Ezguerra with his Arte de la lengua bisaya in 1747[42] and of Mentrida with his Arte de la lengua bisaya: Iliguaina de la isla de Panay in 1818 which primarily discussed grammatical structure.[43] Based on the differing sources spanning centuries, the documented syllabaries also differed in form.

The Ticao stone inscription, also known as the Monreal stone or Rizal stone, is a limestone tablet that contains baybayin characters. Found by pupils of Rizal Elementary School on Ticao Island in Monreal town, Masbate, which had scraped the mud off their shoes and slippers on two irregular shaped limestone tablets before entering their classroom, they are now housed at a section of the National Museum of the Philippines, which weighs 30 kilos, is 11 centimeters thick, 54 cm long and 44 cm wide while the other is 6 cm thick, 20 cm long and 18 cm wide.[44][45]

Decline

The confusion over vowels (i/e and o/u) and final consonants, missing letters for Spanish sounds and the prestige of Spanish culture and writing may have contributed to the demise of baybayin over time, as eventually baybayin fell out of use in much of the Philippines. Learning the Latin alphabet also helped Filipinos to make socioeconomic progress under Spanish rule, as they could rise to relatively prestigious positions such as clerks, scribes and secretaries.[14] By 1745, Sebastián de Totanés wrote in his Arte de la lengua tagala that "The Indian [Filipino] who knows how to read [baybayin] is now rare, and rarer still is one who knows how to write [baybayin]. They now all read and write in our Castilian letters [Latin alphabet]."[3] Between 1751 and 1754, Juan José Delgado wrote that "the [native] men devoted themselves to the use of our [Latin] writing".[46]

The complete absence of pre-Hispanic specimens of usage of the baybayin script has led to a common misconception that fanatical Spanish priests must have burned or destroyed massive amounts of native documents. One of the scholars who proposed this theory is the anthropologist and historian H. Otley Beyer who wrote in "The Philippines before Magellan" (1921) that, "one Spanish priest in Southern Luzon boasted of having destroyed more than three hundred scrolls written in the native character". Historians have searched for the source of Beyer's claim, but no one has verified the name of the said priest.[14] There is no direct documentary evidence of substantial destruction of native pre-Hispanic documents by Spanish missionaries and modern scholars such as Paul Morrow and Hector Santos[47] accordingly rejected Beyer's suggestions. In particular, the scholar Santos suggested that only the occasional short documents of incantations, curses and spells that were deemed evil were possibly burned by the Spanish friars, and that the early missionaries only carried out the destruction of Christian manuscripts that were not acceptable to the Church. Santos rejected the idea that ancient pre-Hispanic manuscripts were systematically burned.[48] The scholar Morrow also noted that there are no recorded instances of ancient Filipinos writing on scrolls, and that the most likely reason why no pre-Hispanic documents survived is because they wrote on perishable materials such as leaves and bamboo. He also added that it is also arguable that Spanish friars actually helped to preserve baybayin by documenting and continuing its use even after it had been abandoned by most Filipinos.[14]

The scholar Isaac Donoso claims that the documents written in the native language and in the native script (particularly baybayin) played a significant role in the judicial and legal life of the colony and noted that many colonial-era documents written in baybayin are still present in some repositories, including the library of the University of Santo Tomas.[49] He also noted that the early Spanish missionaries did not suppress the usage of the baybayin script but instead they may have even promoted the baybayin script as a measure to stop Islamization, since the Tagalog language was moving from baybayin to Jawi, the Arabized script of Islamized Southeast Asian societies.[50]

While there were recorded at least two records of burning of Tagalog booklets of magic formulae during the early Spanish colonial period, scholar Jean Paul-Potet (2017) also commented that these booklets were written in Latin characters and not in the native baybayin script.[51] There are also no reports of Tagalog written scriptures, as they kept their theological knowledge unwritten and in oral form while reserving the use of the baybayin script for secular purposes and talismans.[52]

Modern descendants

The only surviving modern scripts that descended directly from the original baybayin script through natural development are the Tagbanwa script inherited from the Tagbanwa people by the Palawan people and named Ibalnan, the Buhid script and the Hanunóo script in Mindoro. Kulitan, the precolonial Indic script used to write Kapampangan,[5] has been reformed in recent decades and now employs consonant stacking.

| Script | Region | Sample |

|---|---|---|

| Ibalnan script | Palawan | |

| Hanunó'o script | Mindoro |  |

| Buhid script | Mindoro |  |

| Tagbanwa script | Central and Northern Palawan |  |

Characteristics

.jpg.webp)

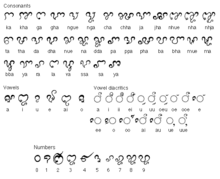

Baybayin is an abugida (alphasyllabary), which means that it makes use of consonant-vowel combinations. Each character or titík,[53] written in its basic form, is a consonant ending with the vowel "A". To produce consonants ending with other vowel sounds, a mark called a kudlit[53] is placed either above the character (to produce an "E" or "I" sound) or below the character (to produce an "O" or "U" sound). To write words beginning with a vowel, three characters are used, one each for A, E/I and O/U.

Characters

| Independent vowels | Base consonants (with implicit vowel a) | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

a |

i/e |

u/o |

ka |

ga |

nga |

ta |

da/ra |

na |

pa |

ba |

ma |

ya |

la |

wa |

sa |

ha | |||

Vowels

|

Ba/Va

|

Ka

|

Da/Ra

|

Ga

|

Ha

|

La

|

Ma

|

Na

|

Nga

|

Pa/Fa

|

Sa/Za

|

Ta

|

Wa

|

Ya

|

Note that the second to last row features the pamudpod virama " ᜴", which was introduced by Antoon Postma to the Hanunuo script. The last row of clusters with the krus-kudlit virama "+", were an addition to the original script, introduced by the Spanish priest Francisco Lopez in 1620.

There is only one symbol or character for Da or Ra as they were allophones in many languages of the Philippines, where Ra occurred in intervocalic positions and Da occurred elsewhere. The grammatical rule has survived in modern Filipino, so that when a d is between two vowels, it becomes an r, as in the words dangál (honour) and marangál (honourable), or dunong (knowledge) and marunong (knowledgeable), and even raw for daw (he said, she said, they said, it was said, allegedly, reportedly, supposedly) and rin for din (also, too) after vowels.[14] However, baybayin script variants like Sambal, Basahan, and Ibalnan ;to name a few, have separate symbols for Da and Ra.

The same symbol is also used to represent the Pa and Fa (or Pha), Ba and Va, and Sa and Za which were also allophonic. A single character represented nga. The current version of the Filipino alphabet still retains "ng" as a digraph. Beside these phonetic considerations, the script is monocameral and does not use letter case for distinguishing proper names or initials of words starting sentences.

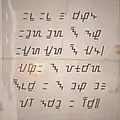

.jpg.webp) The surat guhit (basahan) of the Bikol region.

The surat guhit (basahan) of the Bikol region. The abakada in the Tagalog script.

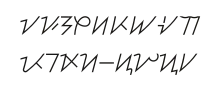

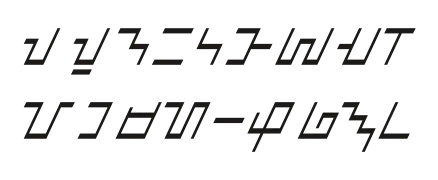

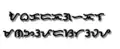

The abakada in the Tagalog script. Various badlit styles.

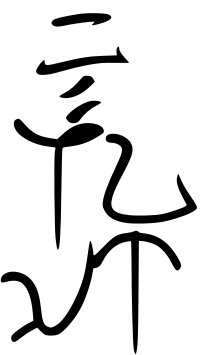

Various badlit styles. The word kulitan in Modern Kulitan.

The word kulitan in Modern Kulitan. Buhid urukay, from Violeta B. Lopez's book The Mangyan of Mindoro.[54]

Buhid urukay, from Violeta B. Lopez's book The Mangyan of Mindoro.[54] Mayad pagyabi (good morning), written in Hanunuo script using the b17 and b17x methods respectively.

Mayad pagyabi (good morning), written in Hanunuo script using the b17 and b17x methods respectively. Every baybayin variant has letters with stylistic variants, just as the tail of the letter ⟨Q⟩ can be written in different ways.

Every baybayin variant has letters with stylistic variants, just as the tail of the letter ⟨Q⟩ can be written in different ways.

Virama kudlit

The original writing method was particularly difficult for the Spanish priests who were translating books into the vernaculars, because originally baybayin omitted the final consonant without a vowel. This could cause confusion for readers over which word or pronunciation a writer originally intended. For example, 'bundok' (mountain) would have been spelled as 'bu-du', with the final consonants of each syllable omitted. Because of this, Francisco López introduced his own kudlit in 1620, called a sabat or krus, that cancelled the implicit a vowel sound and which allowed a final consonant to be written. The kudlit was in the form of a "+" sign,[55] in reference to Christianity. This cross-shaped kudlit functions exactly the same as the virama in the Devanagari script of India. In fact, Unicode calls this kudlit U+1714 ◌᜔ , TAGALOG SIGN PAMUDPOD.

Punctuation and spacing

Baybayin originally used only one punctuation mark (), which was called Bantasán.[53][56] Today baybayin uses two punctuation marks, the Philippine single () punctuation, acting as a comma or verse splitter in poetry, and the double punctuation (), acting as a period or end of paragraph. These punctuation marks are similar to single and double danda signs in other Indic Abugidas and may be presented vertically like Indic dandas, or slanted like forward slashes. The signs are unified across Philippines scripts and were encoded by Unicode in the Hanunóo script block.[57] Space separation of words was historically not used as words were written in a continuous flow, but is common today.[14]

Collation

- In the Doctrina Christiana, the letters of baybayin were collated (without any connection with other similar script, except sorting vowels before consonants) as:

- A, U/O, I/E; Ha, Pa, Ka, Sa, La, Ta, Na, Ba, Ma, Ga, Da/Ra, Ya, NGa, Wa.[58]

- In Unicode the letters are collated in coherence with other Indic scripts, by phonetic proximity for consonants:

- A, I/E, U/O; Ka, Ga, Nga; Ta, Da/Ra, Na; Pa, Ba, Ma; Ya, La, Wa, Sa, Ha.[59]

Usage

Pre-colonial and colonial usage

Baybayin historically was used in Tagalog and to a lesser extent Kapampangan speaking areas. Its use spread to Ilokanos when the Spanish promoted its use with the printing of Bibles. Baybayin was noted by the Spanish priest Pedro Chirino in 1604 and Antonio de Morga in 1609 to be known by most Filipinos, stating that there is hardly a man and much less a woman, who does not read and write in the letters used in the "island of Manila".[31] It was noted that they did not write books or keep records, but used baybayin for personal writings like small notes and messages, poetry and signing documents.[37]

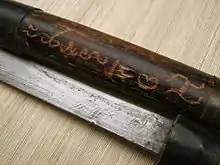

Traditionally, baybayin was written upon palm leaves with styli or upon bamboo with knives, the writing tools were called panulat.[60] The curved shape of the letter forms of baybayin is a direct result of this heritage; straight lines would have torn the leaves.[61] Once the letters were carved into the bamboo, it was wiped with ash to make the characters stand out more. An anonymous source from 1590 states:

When they write, it is on some tablets made of the bamboos which they have in those islands, on the bark. In using such a tablet, which is four fingers wide, they do not write with ink, but with some scribers with which they cut the surface and bark of the bamboo, and make the letters.[14]

During the era of Spanish colonization, most baybayin began being written with ink on paper using a sharpened quill,[62] or printed in books (using the woodcut technique) to facilitate the spread of Christianity.[63] In some parts of the country like Mindoro the traditional writing technique has been retained.[64] Filipinos began keeping paper records of their property and financial transactions, and would write down lessons they were taught in church, all in baybayin.[14] The scholar Isaac Donoso claims that the documents written in the native language and in baybayin played a significant role in the judicial and legal life of the colony.[65] The University of Santo Tomas Baybayin Documents cover two legal real estate transactions in 1613, written in baybayin, (labelled as Document A dated February 15, 1613)[66] and 1625 (labelled as Document B dated December 4, 1625)[67]

Modern usage

_Baybayin.jpg.webp)

A number of legislative bills have been proposed periodically aiming to promote the writing system, among them is the "National Writing System Act" (House Bill 1022[68]/Senate Bill 433[69]). It is used in the most current New Generation Currency series of the Philippine peso issued in the last quarter of 2010. The word used on the bills was "Pilipino" ().

It is also used in Philippine passports, specifically the latest e-passport edition issued 11 August 2009 onwards. The odd pages of pages 3–43 have "" ("Ang katuwiran ay nagpapadakila sa isang bayan"/"Righteousness exalts a nation") in reference to Proverbs 14:34.

The lyrics of Lupang Hinirang in Baybayin rendering.

The lyrics of Lupang Hinirang in Baybayin rendering. Flag of the Katipunan Magdiwang faction, with the baybayin letter ka.

Flag of the Katipunan Magdiwang faction, with the baybayin letter ka..svg.png.webp) Seal of the National Historical Commission of the Philippines, with the two Baybayin ka and pa letters in the center.

Seal of the National Historical Commission of the Philippines, with the two Baybayin ka and pa letters in the center. Emblem of the Armed Forces of the Philippines, with a Baybayin ka in the center.

Emblem of the Armed Forces of the Philippines, with a Baybayin ka in the center..svg.png.webp) Logo of the National Library of the Philippines. The Baybayin text reads as karunungan (ka r(a)u n(a)u nga n(a), wisdom).

Logo of the National Library of the Philippines. The Baybayin text reads as karunungan (ka r(a)u n(a)u nga n(a), wisdom). Logo of the National Museum of the Philippines, with a Baybayin pa letter in the center, in a traditional rounded style.

Logo of the National Museum of the Philippines, with a Baybayin pa letter in the center, in a traditional rounded style. Logo of the Cultural Center of the Philippines, with three rotated occurrences of the Baybayin ka letter.

Logo of the Cultural Center of the Philippines, with three rotated occurrences of the Baybayin ka letter. The insignia of the Order of Lakandula contains an inscription with Baybayin characters represents the name Lakandula, read counterclockwise from the top.

The insignia of the Order of Lakandula contains an inscription with Baybayin characters represents the name Lakandula, read counterclockwise from the top.

Examples

The Lord's Prayer (Ama Namin)

| Baybayin script | Latin script | English (1928 BCP)[70] (current Filipino Catholic version[71]) |

|---|---|---|

|

|

Ama namin, sumasalangit ka, |

Our Father who art in heaven, |

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

| Baybayin script | Latin script | English translation |

|---|---|---|

|

|

Ang lahat ng tao'y isinilang na malaya Sila'y pinagkalooban ng katuwiran at budhi |

All human beings are born free They are endowed with reason and conscience |

Motto of the Philippines

| Baybayin script | Latin script | English translation |

|---|---|---|

| Maka-Diyos, Maka-Tao, Makakalikasan, at Makabansa. |

For God, For People, For Nature, and For Country. | |

| Isang Bansa, Isang Diwa |

One Country, One Spirit. |

Example sentences

-

- Yamang ‘di nagkakaunawaan, ay mag-pakahinahon.

- Remain calm in disagreements.

-

- Magtanim ay 'di birò.

- Planting is not a joke.

-

- Ang kabataan ang pag-asa ng bayan.

- The youth is the hope of the country.

-

- Mámahalin kitá hanggáng sa pumutí ang buhók ko.

- I will love you until my hair turns white.

Unicode

Baybayin was added to the Unicode Standard in March, 2002 with the release of version 3.2.

Keyboard

Gboard

The virtual keyboard app Gboard developed by Google for Android and iOS devices was updated on August 1, 2019[72] its list of supported languages. This includes all Unicode suyat blocks. Included are "Buhid", "Hanunuo", baybayin as "Filipino (Baybayin)", and the Tagbanwa script as "Aborlan".[73] The baybayin layout, "Filipino (Baybayin)", is designed such that when the user presses the character, vowel markers (kudlit) for e/i and o/u, as well as the virama (vowel sound cancellation) are selectable.

Philippines Unicode Keyboard Layout with baybayin

It is possible to type baybayin directly from one's keyboard without the need to use web applications which implement an input method. The Philippines Unicode Keyboard Layout[74] includes different sets of baybayin layout for different keyboard users: QWERTY, Capewell-Dvorak, Capewell-QWERF 2006, Colemak, and Dvorak, all of which work in both Microsoft Windows and Linux.

This keyboard layout with baybayin can be downloaded here.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Baybayin. |

References

- Morrow, Paul. "Baybayin Styles & Their Sources". Retrieved 25 April 2020.

- https://ncca.gov.ph/about-culture-and-arts/in-focus/the-mystery-of-the-ancient-inscription-an-article-on-the-calatagan-pot/%7CThe National Commission for Culture and the Arts of the Philippines: Calatagan Pot

- de Totanés, Sebastián (1745). Arte de la lenga tagalog. p. 3.

No se trata de los caracteres tagalos, porque es ya raro el indio que los sabe leer, y rarisimo el que los sabe escribir. En los nuestros castellanos leen ya, y escriben todos.

- Brennan, Fredrick R. (18 July 2018). "The baybayin "ra"—ᜍ its origins and a plea for its formal recognition" (PDF).

- " "Christopher Ray Miller's answer to is Baybayin really a writing system in the entire pre-Hispanic Philippines? What's the basis for making it a national writing system if pre-Hispanic kingdoms weren't homogenous? - Quora".

- Archives, University of Santo Tomas, archived from the original on 24 May 2013, retrieved 17 June 2012.

- "UST collection of ancient scripts in 'baybayin' syllabary shown to public", Inquirer, 15 January 2012, retrieved 17 June 2012.

- UST Baybayin collection shown to public, Baybayin, retrieved 18 June 2012.

- "House of Representatives Press Releases". www.congress.gov.ph. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Orejas, Tonette (27 April 2018). "Protect all PH writing systems, heritage advocates urge Congress". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- Halili, Mc (2004). Philippine history. Rex. p. 47. ISBN 978-971-23-3934-9.

- Duka, C (2008). Struggle for Freedom' 2008 Ed. Rex. pp. 32–33. ISBN 978-971-23-5045-0.

- Morrow, Paul. "Baybayin, The Ancient Script of the Philippines". paulmorrow.ca.

- Philippine Indigenous Writing Systems in the Modern World by Norman de los Santos, presented at the "Thirteenth International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics". 13-ICAL – 2015, Academia Sinica, Taipei, Taiwan July 18–23, 2015

- Acharya, Amitav. "The "Indianization of Southeast Asia" Revisited: Initiative, Adaptation and Transformation in Classical Civilizations" (PDF). amitavacharya.com.

- Coedes, George (1967). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. Australian National University Press.

- Krishna Chandra Sagar, 2002, An Era of Peace, Page 52.

- Diringer, David (1948). Alphabet a key to the history of mankind. p. 402.

- Lukas, Helmut (21–23 May 2001). "1 THEORIES OF INDIANIZATIONExemplified by Selected Case Studies from Indonesia (Insular Southeast Asia)". International SanskritConference.

- Krom, N.J. (1927). Barabudur, Archeological Description. The Hague.

- Smith, Monica L. (1999). ""Indianization" from the Indian Point of View: Trade and Cultural Contacts with Southeast Asia in the Early First Millennium C.E". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 42 (11–17): 1–26. doi:10.1163/1568520991445588. JSTOR 3632296.

- Court, C. (1996). The spread of Brahmi Script into Southeast Asia. In P. T. Daniels & W. Bright (Eds.) The World's Writing Systems (pp. 445-449). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Philippine Indic studies: Fletcher Gardner. 2005.

- Miller, Christopher 2016. A Gujarati origin for scripts of Sumatra, Sulawesi and the Philippines. Proceedings of Berkeley Linguistics Society 36:376-91

- Diringer, David (1948). Alphabet a key to the history of mankind. pp. 421–443.

- Scott 1984

- Caldwell, Ian. 1988. Ten Bugis Texts; South Sulawesi 1300-1600. PhD thesis, Australian National University, p.17

- Diringer, David (1948). Alphabet a key to the history of mankind. p. 423.

- Nation Museum Collections Seals

- Wade, Geoff (March 1993). "On the Possible Cham Origin of the Philippine Scripts". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 24 (1): 44–87. doi:10.1017/S0022463400001508. JSTOR 20071506.

- https://ncca.gov.ph/about-culture-and-arts/in-focus/the-mystery-of-the-ancient-inscription-an-article-on-the-calatagan-pot

- Guillermo, Ramon G.; Paluga, Myfel Joseph D. (2011). "Barang king banga: A Visayan language reading of the Calatagan pot inscription (CPI)". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 42: 121–159. doi:10.1017/S0022463410000561.

- de San Agustin, Caspar (1646). Conquista de las Islas Filipinas 1565-1615.

'Tienen sus letras y caracteres como los malayos, de quien los aprendieron; con ellos escriben con unos punzones en cortezas de caña y hojas de palmas, pero nunca se les halló escritura antinua alguna ni luz de su orgen y venida a estas islas, conservando sus costumbres y ritos por tradición de padres a hijos sin otra noticia alguna.'

- de Santa Inés, Francisco (1676). Crónica de la provincia de San Gregorio Magno de religiosos descalzos de N. S. P. San Francisco en las Islas Filipinas, China, Japón, etc. pp. 41–42.

- Miller, Christopher (2014). "A survey of indigenous scripts of Indonesia and the Philippines". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Scott 1984, p. 210

- "Baybayin Styles & Their Sources".

- "Ilokano Lord's Prayer, 1620".

- Espallargas, Joseph G. (1974). A study of the ancient Philippine syllabary with particular attention to its Tagalog version. p. 98.

- de San Agustín, Gaspar (1703). Compendio de la arte de la lengua tagala. p. 142.

Por último pondré el modo, que tenían de escribir antiguamente, y al presente lo usan en el Comintan (Provincias de la laguna y Batangas) y otras partes.

- P. Domingo Ezguerra (1601–1670) (1747) [c. 1663]. Arte de la lengua bisaya de la provincia de Leyte. apendice por el P. Constantino Bayle. Imp. de la Compañía de Jesús. ISBN 9780080877754.

- Trinidad Hermenegildo Pardo de Tavera (1884). Contribución para el estudio de los antiguos alfabetos filipinos. Losana.

- Muddied stones reveal ancient scripts

- Romancing the Ticao Stones: Preliminary Transcription, Decipherment, Translation, and Some Notes

- Delgado, Juan José (1892). Historia General sacro-profana, política y natural de las Islas del Poniente llamadas Filipinas. pp. 331–333.

- Santos, Hector. "Extinction of a Philippine Script". www.bibingka.baybayin.com.

However, when I started looking for documents that could confirm it, I couldn't find any. I pored over historians' accounts of burnings (especially Beyer) looking for footnotes that may provide leads as to where their information came from. Sadly, their sources, if they had any, were not documented.

- Santos, Hector. "Extinction of a Philippine Script". www.bibingka.baybayin.com. Archived from the original on 15 September 2019. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

But if any burnings happened as a result of this order to Fr. Chirino, they would have resulted in destruction of Christian manuscripts that were not acceptable to the Church and not of ancient manuscripts that did not exist in the first place. Short documents burned? Yes. Ancient manuscripts? No.

- Donoso, Isaac (14 June 2019). "Letra de Meca: Jawi Script in the Tagalog Region During the 16Th Century". Journal of Al-Tamaddun. 14 (1): 89–103. doi:10.22452/JAT.vol14no1.8. ISSN 2289-2672.

What is important to us is the relevant activity during these centuries to study, write and even print in Baybayin. And this task is not strange in other regions of the Spanish Empire. In fact indigenous documents placed a significant role in the judicial and legal life of the colonies. Documents in other language than Spanish were legally considered, and Pedro de Castro says that "I have seen in the archives of Lipa and Batangas many documents with these characters". Nowadays we can find Baybayin documents in some repositories, including the oldest library in the country, the University of Santo Tomás.

- Donoso, Isaac (14 June 2019). "Letra de Meca: Jawi Script in the Tagalog Region During the 16Th Century". Journal of Al-Tamaddun. 14 (1): 92. doi:10.22452/JAT.vol14no1.8. ISSN 2289-2672. Retrieved 15 September 2019.

Secondly, if Baybayin was not deleted but promoted and we know that Manila was becoming an important Islamic entrepôt, it is feasible to think that Baybayin was in a mutable phase in Manila area at the Spanish advent. This is to say, like in other areas of the Malay world, Jawi script and Islam were replacing Baybayin and Hindu-Buddhist culture. Namely Spaniards might have promoted Baybayin as a way to stop Islamization since the Tagalog language was moving from Baybayin to Jawi script.

- POTET, Jean-Paul G. (2019). Ancient Beliefs and Customs of the Tagalogs. Lulu.com. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-244-34873-1.

- POTET, Jean-Paul G. (2019). Ancient Beliefs and Customs of the Tagalogs. Lulu.com. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-0-244-34873-1.

the Tagalogs kept their theological knowledge unwritten, and only used their syllabic alphabet (Baybayin) for secular pursuits and, perhaps, talismans.

- Potet, Jean-Paul G. Baybayin, the Syllabic Alphabet of the Tagalogs. p. 95.

- Casiño, Eric S. (1977). "Reviewed work: THE MANGYANS OF MINDORO: AN ETHNOHISTORY, Violeta B. Lopez; BORN PRIMITIVE IN THE PHILIPPINES, Severino N. Luna". Philippine Studies. 25 (4): 470–472. JSTOR 42632398.

- Tagalog script Archived August 23, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Accessed September 2, 2008.

- de Noceda, Juan (1754). Vocabulario de la lengua tagala. p. 39.

- "Chapter 17: Indonesia and Oceania, Philippine Scripts" (PDF). Unicode Consortium. March 2020.

- "Doctrina Cristiana". Project Gutenberg.

- Unicode Baybayin Tagalog variant

- Filipinas. Filipinas Pub. 1 January 1995. p. 60.

- "Cochin Palm Leaf Fiscals". Princely States Report > Archived Features. 1 April 2001. Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- Chirino, Pedro (1604). Relacion de las Islas Filipinas, y de Lo Que en Ellas Han Trabajado los Padres de la Compania de Jesus. p. 59.

- Woods, Damon L. (1992). "Tomas Pinpin and the Literate Indio: Tagalog Writing in the Early Spanish Philippines" (PDF). Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Scott, William Henry (1984). Prehispanic Source Materials for the study of Philippine History. New Day Publishers. ISBN 971-10-0226-4.

- Donoso, Isaac (14 June 2019). "Letra de Meca: Jawi Script in the Tagalog Region During the 16Th Century". Journal of Al-Tamaddun. 14 (1): 89–103. doi:10.22452/JAT.vol14no1.8. ISSN 2289-2672.

What is important to us is the relevant activity during these centuries to study, write and even print in Baybayin. And this task is not strange in other regions of the Spanish Empire. In fact indigenous documents placed a significant role in the judicial and legal life of the colonies. Documents in other language than Spanish were legally considered, and Pedro de Castro says that "I have seen in the archives of Lipa and Batangas many documents with these characters". Nowadays we can find Baybayin documents in some repositories, including the oldest library in the country, the University of Santo Tomás.

- Morrow, Paul (5 May 2010). "Document A". Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- Morrow, Paul (4 May 2010). "Document B". Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- "House Bill 1022" (PDF). 17th Philippine House of Representatives. 4 July 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- "Senate Bill 433". 17th Philippine Senate. 19 July 2016. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- "The 1928 Book of Common Prayer: Family Prayer". Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- Catechism of the Catholic Church

- techmagus (August 2019). "Baybayin in Gboard App Now Available". Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- techmagus (August 2019). "Activate and Use Baybayin in Gboard". Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- "Philippines Unicode Keyboard Layout". techmagus.

External links

- House Bill 160, aka the National Script Act of 2011

- Tagalog – Unicode character table

- Baybayin Modern Fonts

- Paul Morrow's Baybayin Fonts