Marshfield, Gloucestershire

Marshfield is a town in the local government area of South Gloucestershire, England, on the borders of the counties of Wiltshire and Somerset. Toponomy derives from the Old English language word "March" meaning a border, hence Border Field would be the literal translation. It is not to do with "marsh" in the sense of bog.

| Marshfield | |

|---|---|

Old school building on the High Street | |

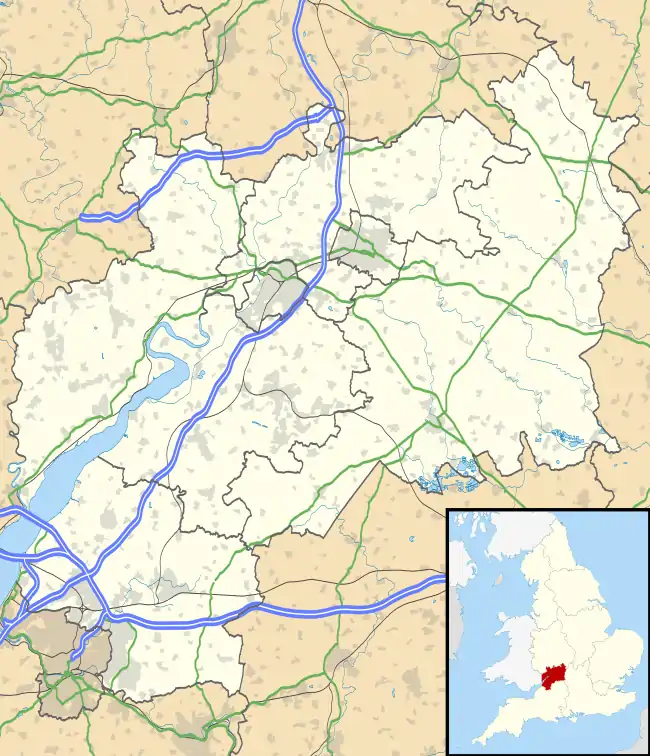

Marshfield Location within Gloucestershire | |

| Population | 1,716 (2011 census )[1] |

| OS grid reference | ST781737 |

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Chippenham |

| Postcode district | SN14 |

| Dialling code | 01225 |

| Police | Avon and Somerset |

| Fire | Avon |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament | |

The history of the town is reflected in the buildings and architecture, including the church and market place. It was used by troops during the English Civil War.

A range of customs and cultural events are held in the town.

Location

Marshfield is at the southern end of the Cotswold Hills, 8 miles (13 km) north of Bath, 15 miles (24 km) east of Bristol and 28 miles (45 km) south of Gloucester. The A420 road bypasses the town on its northern side. To the north of Marshfield is a long stretch of flat-looking fields bordered by dry-stone walls. To the south, the view and the country is quite different, for one is quickly into the wooded valleys and hedge-lined fields of Bath and North East Somerset.

High Street is the single main thoroughfare of Marshfield and is approximately 350 m in length and straight. The eastern part of the town contains the parish church, Manor House and Home Farm, a group of historic buildings noted for their architectural features.

Historic buildings

Almost every house along the high street is more than 100 years old, from the Georgian architecture Gothic toll house at the western end to the groups of medieval barn, dovecote, and early Georgian stable range which go with the manor house, which dates from the 17th century,[2] and Home Farm. Near the toll house stand the fine almshouses of 1612,[3] built for the use of eight elderly villagers by two sons of Marshfield, Nicholas and Ellis Crispe,[4] who had gone to London and made their fortunes largely through the West Indies trade. They endowed the houses with funds to provide a free residence, garden, and £11 yearly. Many houses date from Tudor era and Stuart times (a few were originally timber-framed) and have gables and mullioned windows. Several have bow fronts and there are five examples of shell-pattern door arches typical of Queen Anne work. The finest front in the high street is perhaps the Catherine Wheel some of whose buildings at the rear are much older than 1700.[5]

The Malting house is a typical example of the village's former prosperity in that trade.[6] Other notable high street buildings include the former Old Meeting, a Presbyterian / Independent, later Unitarian chapel of 1752, the gabled range of the Hospice, the Red House, the former police station (now number 123), numbers 44, 83, 115, and 126.

The former vicarage, now known as "Marshfield House", whose front was rebuilt in the 1730s by Mrs Dionysia Long, is particularly handsome with its barn, stable block, and large walled garden fringing the market place. It has four storeys, including a basement and extensive attics. The vicarage did not have electricity until the 1950s, in fact only two of the floors had electricity in the early 1980s. The last vicar to inhabit the old vicarage was Rev John Miskin Prior. Following his departure from the village in 1982, a new vicarage was built on land in Church Lane, and the old vicarage was sold as a private residence.

Public houses

The Crown, now converted into flats, the Lord Nelson, the Old Inn, and several farms still in the heart of the village are also noteworthy: Weir farm in Weir lane, with its gables, was once a malting house, and Pitt farm, at Little end, is 17th century.

Vernacular buildings

The Tolzey or Town House was built in 1690 for the people of Marshfield by John and Mary Goslett. As well as being the old town's administrative headquarters it also housed a Marshfield fire engine and served as a lock-up. The parish council still meets at the Tolzoy.[7] It is a Grade II listed building.[8]

Castle farm is about half a mile to the north of Marshfield. In its 2-acre (8,100 m2) farmyard is an ancient longhouse with the original fireplace and the dividing screen between the human and animal dwellings.[9] On the neighbouring land where lynchets show in some fields, many Bronze Age and Stone Age implements have been picked up and a skeleton in a stone coffin discovered.

Formerly there were two mansions to the south of the village; the Rocks, now a ruin, and Ashwicke Hall. The Rocks, covering 1,188 acres (4.81 km2) belonged to the Taylor family, and was originally of Jacobean design.[10] It was visited by the late Queen Mary during her stay at Badminton House in the Second World War. Ashwicke, ancient seat of the Webb family, was bought and rebuilt by John Orred in 1857, replacing an older house that stood nearby.[11] After his death it was bought by the Horlocks who later moved to the Manor House. The hall then passed through other hands and the Firth family sold it to its last private owner, Major Pope, in 1909. The two houses employed many people from the parish in the past and the footpath running from the village to Ashwicke is a reminder of those days of service. On this former estate is the Rocks East woodland training centre which has several guided walks and wooden sculptures.

History

The town is rich in history because of its location in the heart of Cotswold wool country, near to Bath and Bristol. Located within an agricultural area, Marshfield gained market status in 1234.[12] The layout conforms to that of a typical market town with long narrow burgage plot gardens extending back from the narrow frontages, and served by two rear access lanes (Back Lane and Weir Lane).[13]

The majority of buildings lining the street are of 18th-century origin although several buildings date from the 17th century. The building style is largely Georgian. The facades of the buildings are unified by the consistent use of local stone and other materials, which adds character to the village.

Civil War

Marshfield was a casualty of the Battle of Lansdown (July 1643) during the Civil War. A Royalist army under Prince Maurice and Sir Bevil Grenville were hoping to link up with Charles I at Oxford and avoid a confrontation with the Parliamentary Forces gathered at Bath under Sir William Waller. Marshfield, which had about 300 houses at that time, on 4 July was used as an overnight billet and provision store for the King's army of 6000.[14] Next day the royalists were tempted into an abortive Battle at Lansdown, each side withdrawing with heavy losses. Sir Bevil Grenville (whose monument now stands on the site of the battle) died in Cold Ashton rectory and as the Royalists fell back on Marshfield for repairs almost every house had wounded men on its hands.[15] When the depleted army moved on the reinforced Cromwellian army soon followed. There was little time to stow away the church's simple treasures before the invading despoilers were at work. As a piece of local doggerel composed 200 years later had it "The empty niche above the door, where Mary's image stood, And ravaged reredos testify to their revengeful mood."

It is not known just what damage may have been done as a result of the Civil War. Canon Trotman, a prominent authority in Marshfield's more recent past, speculated publicly about the likely missing treasures. He noticed the large stones on either side of the east window, with rough infilling under them. The large stones evidently formed canopies for figures now missing and which have been the marble figures found in 1866 during alterations at the Angel Inn (now 42 high Street) and later removed from the parish. Two or three other figures probably completed the statuary. Canon Trotman further presumed that the figure of the Virgin may have been taken from its niche in the porch by the Parliamentary troops, but adds forcefully,

"Even they could scarcely have done more havoc with the church than the hand of the so-called restorer in 1860 who, while substituting the pitch pine seats...for the old carefully locked pews and capacious gallery, effaced at the same time much that should have been interesting to us today."

Canon Trotman (1906).

With Cromwell's victory in the Civil War, the period of the Commonwealth ensued during which time marriage was treated as a secular rather than religious ceremony. John Goslett as a magistrate therefore married 92 couples during that period from the parish and around, in may cases the banns having been called on three successive market days in the market Place at Marshfield (as an alternative banns could still be read in church). There was clearly no long-term disadvantage in all this for Mr Goslett for a tablet to his memory was nevertheless placed in the church, beside the east window of the north aisle.

David Long, from Pennsylvania, reports that on the flat open land between his village and the lane you can often find musket balls, on the battlefield of Lansdown. Looking towards the battle site from the field it would appear to be a logical distance away particularly as they would have been firing uphill at about 45 degrees thus landing some distance from the battle site.

Fire

The village fire engine was purchased in 1826 for £50:00 and was still in use in 1931.[16] It had to be operated by a gang of men on either side of it using a hand pump. In 1896 the Fire Brigade had its capabilities tested to the utmost. Two houses with thatched roofs, in the main streets, caught fire at Mid-day, when all hands were engaged in the fields, but the Brigade mustered quickly in sufficient force to prevent fire spreading to other houses.

The church

St Mary's parish church with its tower provides an important focal point that can be observed from numerous points in the village and is a landmark visible from miles around. The church is on the eastern side of the village. A church has stood on that site for more than 1,000 years.[17] The first was dedicated to St Nicholas, and at west Marshfield there was another, of which no traces remain, to St Pancras. It is thought that a field called St Pancras Close marks the site. In Bristol Museum there is an ancient deed of about 1125 confirming to the Abbot of Tewkesbury various tithes and ecclesiastical benefices, among them Marshfield church, at that time very much smaller than the church we see today.

It is recorded in the annals of Tewkesbury Abbey that on 1 June 1242, in the reign of Henry III, Walter de Cantilupe, Bishop of Worcester, in whose diocese Marshfield then stood, came to dedicate a newly built church at Marshfield. The monks of Tewkesbury Abbey restored and rebuilt the church in the perpendicular style in about 1470.[18] After the Dissolution of the Monasteries the right of presentation of the benefice was given to the warden and fellows of New College, Oxford, by Queen Mary, in lieu of property of which they had been robbed by Henry VIII of England. The college's first incumbent came into residence in 1642, only to be disposed during the English Civil War. New College still has the benefice in its gift.[19]

A chalice of 1576 and a paten probably dating from 1695 are in regular use,[13] and Communion plate given by the Long family in 1728, including two large flagons, is used for the Christmas Eve midnight service each year. The church was restored in 1860 and more carefully in 1887 and 1902-3 under Canon Trotman. The chapel of St Clement in the north aisle was restored to its original design in 1950 as a memorial to the late Major Pope of Ashwicke Hall, a considerable benefactor of Marshfield.[17] A new cemetery to the north of the village was opened in 1932, the churchyard being full.

The Parish Register dates from 1558, the first years of Elizabeth I's reign. The first two volumes were indexed and fifty copies printed by a London antiquarian in the time of Canon Trotman. For the first 150 years entries were generally written in Latin and initially only baptisms were recorded, burials being first entered in 1567 and marriages five years later. Non-conformist worshippers in the village are served by Baptist and Congregational chapels, and by Hebron Hall. Conversion of an old barn into the present church hall was done in 1933 at a cost of £650.

The war memorial

According to inscriptions on the village's War Memorial 27 villagers died in action during the two Wars, 20 men during World War I 1914 - 1918 and 7 men during World War II 1939 - 1945.[20]

The Community Centre

A Community Centre was built in 1991 following a long running campaign to secure the land and the funding. It was developed to provide the village with a full sized sports hall, a second smaller hall, a large kitchen and a light and open foyer area. In 2003, the Community Centre was extended to provide a carefully designed, bespoke building for the Marshfield Pre-School. During 2011, this was further improved by the development of a special sensory garden, just for pre school to enjoy. The Community Centre is available for rent to local groups and other groups/organisations further afield.[21]

The Mummers of Marshfield

Every Boxing Day at 11:00am increasing numbers of visitors come to the village to see the performance of the celebrated Marshfield Mummers or The old time paper boys. Seven figures, led by the Town Crier with his handbell, dressed in costumes made from strips of newsprint and coloured paper, perform their play several times along the high street.[22] Beginning in the Market place after the Christmas Hymns which are led by the vicar the mummers arrive to the sound of the lone bell. The five-minute performances follow the same set and continue up to the almshouses. The final performance is outside of one of the local public houses where the landlord delivers a tot of whisky for the "Boys".

Historical origins of mummers' play

There is evidence of mummers' plays since circa 1141. The Marshfield play was discontinued in the 1880s when a number of the players died of influenza but it was resurrected after the Second World War. In the past centuries the mummers were probably a band of villagers who toured the large houses to collect money for their own Christmas festivities. During the latter half of the 19th century the play lapsed, presumably for lack of interest. The play was not entirely forgotten however. Then, in 1931, the Reverend Alford, vicar of Marshfield, heard his gardener mumbling the words 'Room, room, a gallant room, I say' and discovered that this line was part of a mummers' play. The vicar's sister Violet Alford, a leading folklorist, encouraged the survivors of the troupe and some new members, including Tom Robinson (whose place was later taken by his brother), to revive the tradition. There was some dispute between Miss Alford and the elderly villagers as to how the play should actually be performed, and the resulting revival was a compromise which differs in several respects from other versions: St George has apparently become King William and Father Christmas appears as an extra character. The costumes, as well as the play's symbolism, are relics of an ancient and obscure original- perhaps the earliest performers were clad in leaves or skins, symbolizing the death and rebirth of nature.

The Paper Boys' play is a fertility rite with traces of medieval drama and incorporates the story of St George and the Dragon. It was never written down, and over the centuries, it gradually changed through the addition of ad libs and misunderstandings. The nonsensical corruptions of the text reveal its origins as a story told by illiterate peasant folk, unaware of all its allusions. There have to be seven characters as seven was thought to be a magic number. They include Old Father Christmas (the presenter of the play), King William who slays Little Man John who is resurrected by Dr Finnix (Phoenix, a rebirth theme). There's also Tenpenny Nit, Beelzebub who carries a club and a money pan and Saucy Jack who talks about some of his children dying—there are many references in mummers' plays about social hardship.

The Paper Boys have to belong to families that have lived in Marshfield for generations and they must have the Marshfield accent. When a role becomes available, precedence is given to the relatives of present members of the troupe. Because it is a fertility rite, women are not allowed to participate. Each costume comprises a garment made of brown cloth covered in sewn-on strips of newspaper—hence the name 'Paper Boys'. Each mummer maintains his own costume, repairing it as necessary. It is thought that, in the distant past the costumes bore leaves instead of paper strips.

Media and TV

Marshfield is justly proud of its special local tradition revived now for more than 40 years and looks forward each year to the social gathering each Boxing Day. The mummers have been featured on radio and television and at events of the English Folk Dance and Song Society. A few years ago they featured on the Rev. Lionel Fanthorpes "Fortean TV" aired on Channel 4. In 2002 they featured in a programme by Johnny Kingdom. In 2018 and 2019 the Sky TV detective series, “Agatha Raisin” filmed using locations in Marshfield. The lead actress lives nearby.

Historical fair

Until 25 October 1962, two fairs were held annually in Marshfield, one on 24 March and the other on 24 October. The fairs were first held in 1266 when the Abbot of Keynsham purchased the right and this privilege was confirmed in 1462. The rights of the fair must have passed to the Lord of the Manor at some time because in more recent times they were let to a manager at a yearly rental. In about 1885 the fair was rented by Mark Fishlock from Squire Orred of Ashwicke Hall.

Cattle, sheep, and pigs which were brought in for sale were penned in hurdles in front of the houses on one side of the High Street and White hart lane, causing much confusion, and clearing up afterwards. The streets at that time was unpaved. The farmers paid 1d per head for sheep and 2d per head for cattle sold at the fair, but no charge was made for animals not sold. Until more recent times the dealers and farmers bartered among themselves. Tolls had to be paid for all sheep sold at the rate of 4d a score, this being manorial right of the fair. In May 1901 the fair was taken out of the street to a field adjoining Back Lane. It was a large fair at that time and about four or five thousand sheep and 300 cattle were brought on foot from miles around to be sold. The Market Place was generally filled with sideshows of all sorts.

There were often accidents and during the October 1905, one Thomas White, aged 45, was killed on the roundabouts. Gradually the weekly markets at Bath, Chippenham, and Bridgeyate took the business away from Marshfield fairs: they no longer paid their way therefore and so ended.

Notable people connected with Marshfield

For much of 1940 The Maltings, at 78 High Street was home to several well known cultural figures who were trying to escape the effects of the war.[23] -

- Composer Lennox Berkeley

- Composer Arnold Cooke

- Critic John Davenport and his American wife Clement Davenport, a painter

- William Glock, music critic

- Dylan Thomas and his wife Caitlin née MacNamara

- The writer Antonia White

The Hazlitt family also have connections to the village. In 1766 William Hazlitt senior, father of William Hazlitt became minister of the meeting house.[24] John Hazlitt, a noted painter of miniature portraits, was born in the village.[25]

In Oakford Lane leading down to St Catherine's Valley lived Major Jeremy Taylor who was a Captain in the 23rd Hussars (Tank Regiment) and was decorated in World War II. He grew up on the estate in its heyday. He later worked as an Animal Wrangler in the film "Lawrence of Arabia" and performed the "long" camel riding shots for Peter O'Toole.

Notes and references

- "Parish population 2011". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "The Manor". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 29 August 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- "Crispe Almshouses, Marshfield, South Gloucestershire". Historic England. Archived from the original on 29 August 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- "Crispe Amshouses of Marshfield". Housing Care. Archived from the original on 10 January 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- "The Catherine Wheel". The Catherine Wheel. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- Reeves, Millie. "This former malthouse is half luxury living and half fixer-upper". Bath Chronicle. Archived from the original on 24 February 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- "Marshfield Parish Council". Marshfield Parish Council. Archived from the original on 27 November 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- "Tolzey Hall". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 29 August 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- "Marshfield". History Hunters. Archived from the original on 29 August 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- "The Rocks, Marshfield". Parks and Gardens. Archived from the original on 29 August 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- "Ashwicke Hall". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 29 August 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- "Marshfield". Gazette. 23 November 2006. Archived from the original on 14 August 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- La Trobe-Bateman, E. "Avon Extensive Urban Survey Archaeological Assessment Report" (PDF). South Gloucestershire Council. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 August 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- "Lansdown Hill 5th July 1643" (PDF). Battlefields Trust. Archived from the original on 13 December 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- "English Heritage Battlefield Report: Lansdown 1643" (PDF). Historic England. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- Lewis, James (2009). "Conserving the past at the cost of the future? Self sufficiency and sustainability in Marshfield, South Gloucestershire". Archived from the original on 29 August 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- "Church History". St Mary's Church Marshfield. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- "Parish Church of St. Mary". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- "Marshfield". Genuki. Archived from the original on 12 March 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- "Marshfield War Memorial". Gloucestershire Genealogy. Archived from the original on 8 February 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- "Marshfield Community Centre". Marshfield Community Centre. Archived from the original on 4 December 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- "Marshfield Paper Boys". Calendar Customs. Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- "Dylan Thomas in Marshfield". The Word Travels. Archived from the original on 3 August 2020. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- "Hazlitt, William". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/95498. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Hazlitt, John". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/98526. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Marshfield, Gloucestershire. |