Mastodon

A mastodon (Greek: μαστός "breast" and ὀδούς, "tooth") is any proboscidean belonging to the extinct genus Mammut (family Mammutidae) that inhabited North and Central America during the late Miocene or late Pliocene up to their extinction at the end of the Pleistocene 10,000 to 11,000 years ago.[1] Mastodons lived in herds and were predominantly forest-dwelling animals that lived on a mixed diet obtained by browsing and grazing, somewhat similar to their distant relatives, modern elephants, but probably with greater emphasis on browsing.

| Mastodon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted M. americanum skeleton (the "Warren mastodon"), AMNH | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Proboscidea |

| Family: | †Mammutidae |

| Genus: | †Mammut Blumenbach, 1799 |

| Type species | |

| †Elephas americanum Kerr, 1792 | |

| Species | |

| |

| The inferred range of Mammut (Eurasian range includes that of Zygolophodon borsoni, whose genus assignment is uncertain, and M. matthewi) | |

| Synonyms | |

M. americanum, the American mastodon, and M. pacificus,[2] the Pacific mastodon, are the youngest and best-known species of the genus. Mastodons disappeared from North America as part of a mass extinction of most of the Pleistocene megafauna, widely believed to have been caused by overexploitation by Clovis hunters.

History

A Dutch tenant farmer found the first recorded remnant of Mammut, a tooth some 2.2 kg (5 lb) in weight, in the village of Claverack, New York, in 1705. The mystery animal became known as the "incognitum".[3] In 1739 French soldiers at present-day Big Bone Lick State Park, Kentucky, found the first bones to be collected and studied scientifically. They carried them to the Mississippi River, from where they were transported to the National Museum of Natural History in Paris.[4] Similar teeth were found in South Carolina, and some of the enslaved Africans there supposedly recognized them as being similar to the teeth of African elephants. There soon followed discoveries of complete bones and tusks in Ohio. People started referring to the "incognitum" as a "mammoth", like the ones that were being dug out in Siberia[3] – in 1796 the French anatomist Georges Cuvier proposed the radical idea that mammoths were not simply elephant bones that had been somehow transported north, but a species which no longer existed.[5] Johann Friedrich Blumenbach assigned the scientific name Mammut to the American "incognitum" remains in 1799, under the assumption that they belonged to mammoths. Other anatomists noted that the teeth of mammoths and elephants differed from those of the "incognitum", which possessed rows of large conical cusps, indicating that they were dealing with a distinct species. In 1817 Cuvier named the "incognitum" Mastodon.[3]

Cuvier assigned the name mastodon (or mastodont) - meaning "breast tooth" (Ancient Greek: μαστός "breast" and ὀδούς, "tooth"),[6][7] - for the nipple-like projections on the crowns of the molars.

Taxonomy

Mastodon as a genus name is obsolete;[8] the valid name is Mammut, as that name preceded Cuvier's description, making Mastodon a junior synonym. The change was met with resistance, and authors sometimes applied "Mastodon" as an informal name; consequently it became the common term for members of the genus.

Species include:

- M. americanum, the American mastodon, is one of the best known and among the last species of Mammut. Its earliest occurrences date from the early-middle Pliocene (early Blancan stage). It was formerly regarded (see below) as having a continent-wide distribution, especially during the Pleistocene epoch,[9] known from fossil sites ranging from present-day Alaska, Ontario and New England in the north, to Florida, southern California, and as far south as Honduras.[10] The American mastodon has been widely thought to have resembled a woolly mammoth in appearance.[11] However, consideration of the long tail (usually present in animals living in warm climates), size, body mass and environment implies the animal was not similarly hairy, and there is scant preserved evidence of body hair (what little has been recovered suggests a semiaquatic lifestyle).[12][13] It had tusks that sometimes exceeded 5 m (16 ft) in length; they curved upwards, but less dramatically than those of the woolly mammoth.[14] Its main habitat was cold spruce woodlands, and it is believed to have browsed in herds.[11] It became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene approximately 11,000 years ago.

- M. matthewi — found in the Snake Creek Formation of Nebraska, dating to the late Hemphillian.[15] Some authors consider it practically indistinguishable from M. americanum.[9] There is one report of it in China.[16]

- M. pacificus — based on a 2019 analysis, Pleistocene specimens from California and southern Idaho have been transferred from M. americanum to this new species. It differs from the eastern population in having narrower molars, six as opposed to five sacral vertebrae, a thicker femur, and a consistent absence of mandibular tusks.[2]

- M. raki — Its remains were found in the Palomas Formation, near Truth or Consequences, New Mexico, dating from the early-middle Pliocene, between 4.5 and 3.6 Ma.[17] It coexisted with Equus simplicidens and Gigantocamelus and differs from M. americanum in having a relatively longer and narrower third molar,[9] similar to the description of the defunct genus Pliomastodon, which supports its arrangement as an early species of Mammut.[18] However, like M. matthewi, some authors do not consider it sufficiently distinct from M. americanum to warrant its own species.

- M. cosoensis — found in the Coso Formation of California, dating to the Late Pliocene, originally a species of Pliomastodon,[19] it was later assigned to Mammut.[20]

Since a tentative 1977 report of M. matthewi in China, there have been no reports of currently recognized Mammut species outside of North America according to Paleobiology database (which does not recognize M. borsoni).[21] However, the status of Mammut or Zygolophodon borsoni in the literature appears equivocal.[22][23]

Evolution

%252C_Burning_Tree_Golf_Course%252C_Heath%252C_east-central_Ohio.jpg.webp)

Mammut is a genus of the extinct family Mammutidae, related to the proboscidean family Elephantidae (mammoths and elephants), from which it originally diverged approximately 27 million years ago.[24] The following cladogram shows the placement of the American mastodon among other proboscideans, based on hyoid characteristics:[25]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Over the years, several fossils from localities in North America, Africa and Asia have been attributed to Mammut, but only the North American remains have been named and described, one of them being M. furlongi, named from remains found in the Juntura Formation of Oregon, dating from the late Miocene.[26] However, it is no longer considered valid,[27] leaving only five valid species.

A complete mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) sequence has been obtained from the tooth of an M. americanum skeleton found in permafrost in northern Alaska.[28][29] The remains are thought to be 50,000 to 130,000 years old. This sequence has been used as an outgroup to refine divergence dates in the evolution of the Elephantidae.[29] The rate of mtDNA sequence change in proboscideans was found to be significantly lower than in primates.

A 2020 analysis of mtDNA from American mastodon remains collected in eastern Beringia indicated they belonged to two genetically divergent clades. The clades were dated to different interglacials, suggesting a repeating pattern of colonization during an interglacial followed by extirpation during the subsequent glacial advance. The Beringian clades had less genetic diversity than populations present south of the ice sheets, suggesting they were founded by relatively small migrating populations.[30]

Description

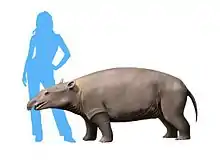

Modern reconstructions based on partial and skeletal remains reveal that mastodons were very similar in appearance to elephants and, to a lesser degree, mammoths, though not closely related to either one. Compared to mammoths, mastodons had shorter legs, a longer body and were more heavily muscled,[31] a build similar to that of the current Asian elephants. The average body size of the species M. americanum was around 2.3 m (7 ft 7 in) in height at the shoulders, corresponding to a large female or a small male; large males were up to 2.8 m (9 ft 2 in) in height.[32] Among the largest male specimens, the 35-year-old AMNH 9950 was 2.89 m (9.5 ft) tall and weighed 7.8 tonnes (7.7 long tons; 8.6 short tons), while another was 3.25 m (10.7 ft) tall and weighed 11 tonnes (11 long tons; 12 short tons).[12]

Like modern elephants, the females were smaller than the males. They had a low and long skull with long curved tusks,[33] with those of the males being more massive and more strongly curved.[32] Mastodons had cusp-shaped teeth, very different from mammoth and elephant teeth (which have a series of enamel plates), well-suited for chewing leaves and branches of trees and shrubs.[34]

Mastodons are typically depicted with a thick woolly mammoth-like coat of hair, but there is no preserved evidence for this.[13]

Paleobiology

Social behavior

Based on the characteristics of mastodon bone sites, it can be inferred that, as in modern proboscideans, the mastodon social group consisted of adult females and young, living in bonded groups called mixed herds. The males abandoned the mixed herds once reaching sexual maturity and lived either alone or in male bond groupings. As in modern elephants,[35] there probably was no seasonal synchrony of mating activity, with both males and females seeking out each other for mating when sexually active.[36]

Diet

Mastodons have been characterized as predominantly browsing animals.[note 1] Of New World proboscids, they appear to have been the most consistent in browsing rather than grazing, consuming C3 as opposed to C4 plants, and in occupying closed forests versus more open habitats.[38] This dietary inflexibility may have prevented them from invading South America during the Great American Interchange, due to the need to cross areas of grassland to do so.[38] Most accounts of gut contents have identified coniferous twigs as the dominant element in their diet. Other accounts (e.g., the Burning Tree mastodon) have reported no coniferous content and suggest selective feeding on low, herbaceous vegetation, implying a mixed browsing and grazing diet,[39] with evidence provided by studies of isotopic bone chemistry indicating a seasonal preference for browsing.[40] Study of mastodon teeth microwear patterns indicates that mastodons could adjust their diet according to the ecosystem, with regionally specific feeding patterns corresponding to boreal forest versus cypress swamps, while a population at a given location was sometimes able to maintain its dietary niche through changes in climate and browse species availability.[41]

Distribution and habitat

The range of most species of Mammut is unknown as their occurrences are restricted to few localities, the exception being the American mastodon (M. americanum), which is one of the most widely distributed Pleistocene proboscideans in North America. M. americanum fossil sites range in time from the Blancan to Rancholabrean faunal stages and in locations from as far north as Alaska, as far east as Florida, and as far south as the state of Puebla in central Mexico,[10] with an isolated record from Honduras, probably reflecting the results of the maximum expansion achieved by the American mastodon during the Late Pleistocene. A few isolated reports tell of mastodons being found along the east coast up to the New England region,[42][43] with high concentrations in the Mid-Atlantic region.[44][45] There is strong evidence indicating that the members of Mammut were forest dwelling proboscideans, predominating in woodlands and forests,[36] and browsed on trees and shrubs.[33] They apparently did not disperse southward to South America, it being speculated that this was because of a dietary specialization on a particular type of vegetation.[46]

Extinction

Fossil evidence indicates that mastodons probably disappeared from North America about 10,500 years ago[1] as part of a mass extinction of most of the Pleistocene megafauna that is widely believed to have been a result of human hunting pressure.[47][48] The latest Paleo-Indians entered the Americas and expanded to relatively large numbers 13,000 years ago,[49] and their hunting may have caused a gradual attrition of the mastodon population.[50][51] Analysis of tusks of mastodons from the American Great Lakes region over a span of several thousand years prior to their extinction in the area shows a trend of declining age at maturation; this is contrary to what one would expect if they were experiencing stresses from an unfavorable environment, but is consistent with a reduction in intraspecific competition that would result from a population being reduced by human hunting.[51] On the other hand, environmental DNA sequencing reported by Eske Willerslev indicates that disappearance of megafaunal DNA in North America correlates in time with major changes in plant DNA, rather than with the appearance of human DNA, suggesting a key role of climate change.

See also

Notes

- Browsing is a type of herbivory in which a herbivore (or, more narrowly defined, a folivore) feeds on leaves, soft shoots, or fruits of high growing, generally woody, plants such as shrubs.[37] This is contrasted with grazing, usually associated with animals feeding on grass or other low vegetation.

References

- Fiedal, Stuart (2009). "Sudden Deaths: The Chronology of Terminal Pleistocene Megafaunal Extinction" (PDF). In Haynes, Gary (ed.). American Megafaunal Extinctions at the End of the Pleistocene. Springer. pp. 21–37. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-8793-6_2. ISBN 978-1-4020-8792-9.

- Dooley, A. C.; Scott, E.; Green, J.; Springer, K. B.; Dooley, B. S.; Smith, G. J. (2019). "Mammut pacificus sp. nov., a newly recognized species of mastodon from the Pleistocene of western North America". PeerJ. 7: e 6614. doi:10.7717/peerj.6614. PMC 6441323. PMID 30944777.

- Conniff, Richard (April 2010). "Mammoths and Mastodons: All American Monsters". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved December 5, 2019.

In the summer of 1705, in the Hudson River Valley village of Claverack, New York, a tooth the size of a man's fist surfaced on a steep bluff, rolled downhill and landed at the feet of a Dutch tenant farmer, who promptly traded it to a local politician for a glass of rum. [...] this 'monstrous creature,' [...] would soon become celebrated as the 'incognitum,' the unknown species.

- Kolbert, Elizabeth (2014). The sixth extinction : an unnatural history (First ed.). New York: Henry Holt and Co. pp. 25–26. ISBN 978-0805092998.

- Cuvier, G. (1796). "Mémoire sur les épèces d'elephans tant vivantes que fossils, lu à la séance publique de l'Institut National le 15 germinal, an IV". Magasin Encyclopédique, 2e Anée (in French): 440–445.

- mastodon Online Etymology Dictionary Retrieved November 10, 2012

- mastodon Merriam-Webster Retrieved June 30, 2012

- Agusti, Jordi & Mauricio Anton (2002). Mammoths, Sabretooths, and Hominids. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 106. ISBN 0-231-11640-3.

- Ruez, D. R. (2007). "Chapter 4: Revision of the blancan mammals from Hagerman fossil beds, National monument, Idaho". Effects of Climate Change on Mammalian Fauna Composition and Structure During the Advent of North American Continental Glaciation in the Pliocene. pp. 249–252. ISBN 978-0549266594.

- Polaco, O. J.; Arroyo-Cabrales, J.; Corona-M., E.; López-Oliva, J. G. (2001). "The American Mastodon Mammut americanum in Mexico" (PDF). In Cavarretta, G.; Gioia, P.; Mussi, M.; Palombo, M. R. (eds.). The World of Elephants - Proceedings of the 1st International Congress, Rome October 16–20, 2001. Rome: Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche. pp. 237–242. ISBN 88-8080-025-6. Retrieved July 25, 2008.

- Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 243. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- Larramendi, A. (2015). "Shoulder Height, Body Mass, and Shape of Proboscideans" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. doi:10.4202/app.00136.2014. S2CID 2092950.

- Witton, M. (26 August 2020). "The "palaeontological folklore" of mastodon hair". markwitton-com.blogspot.com. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- Kurtin, Bjvrn; Björn Kurtén Elaine Anderson (1980). Pleistocene Mammals of North America (illustrated ed.). Columbia University Press. p. 345. ISBN 0231037333.

- Osborn, H. F. (1936). Percy, M. R. (ed.). Proboscidea: A monograph of the discovery, evolution, migration and extinction of the mastodonts and elephants of the world. 1. New York: J. Pierpont Morgan Fund. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.12097.

- "Mammut matthewi in the Paleobiology Database". Fossilworks. Retrieved May 6, 2017.

- Morgan, Gary S.; Spencer G. Lucas (2001). "Summary of Blancan and Irvingtonian (Pliocene and early Pleistocene) Mammalian Biochronology of New Mexico" (PDF). New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources Open-File Report 454B: 29–32.

- Lucas, Spencer G.; Morgan, Gary S. (February 1999). "The oldest Mammut (Mammalia: Proboscidea) from New Mexico". New Mexico Geology: 10–12.

- Schultz, J. R. (1937). "A Late Cenozoic Vertebrate Fauna from the Coso Mountains, Inyo County, California". Carnegie Institution of Washington Publication. 483 (3): 77–109.

- Jeheskel Shoshani; Pascal Tassy (1996). "Summary, conclusions, and a glimpse into the future". The Proboscidea: Evolution and Palaeoecology of Elephants and Their Relatives (illustrated ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 335–348. ISBN 0198546521.

- "Mammut in the Paleobiology Database". Fossilworks. Retrieved February 20, 2017.

- Pickford, M. (May 2007). "New mammutid proboscidean teeth from the Middle Miocene of tropical and southern Africa". Palaeontologia Africana. 42: 29–35. hdl:10539/16088.

- Kalmykov, N. P.; Mashchenko, E. N. (2009). "The most northeastern find of the Zygodont Mastodon (Mammut, Proboscidea) in Asia". Doklady Biological Sciences. 428 (1): 434–436. doi:10.1134/S0012496609050123. PMID 19994783. S2CID 19139590.

- Shoshani, J.; Walter, R. C.; Abraha, M.; Berhe, S.; Tassy, P.; Sanders, W. J.; Marchant, G. H.; Libsekal, Y.; Ghirmai, T.; Zinner, D. (July 24, 2007). "A proboscidean from the late Oligocene of Eritrea, a "missing link" between early Elephantiformes and Elephantimorpha, and biogeographic implications". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (46): 17296–17301. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10317296S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0603689103. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1859925. PMID 17085582.

- Shoshani, J.; Tassy, P. (2005). "Advances in proboscidean taxonomy & classification, anatomy & physiology, and ecology & behavior". Quaternary International. 126–128: 5–20. Bibcode:2005QuInt.126....5S. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2004.04.011.

- Shotwell, J.A; D.E., Russell (1963). "Mammalian fauna of the upper Juntura Formation, the black butte local fauna. in The Juntura Basin: Studies in Earth History and Paleoecology". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 53 (1): 77. doi:10.2307/1005944. JSTOR 1005944.

- Lambert, W.D. (1998). Proboscidea. In: Janis, C.M., Scott, K.M., Jacobs, L.L. (Eds.), Evolution of Tertiary Mammals of North America, Terrestrial Carnivores, Ungulates and Ungulatelike Mammals, vol. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 606–621.

- "UAM:ES:2414: Mammut americanum". arctos.database.museum.

- Hofreiter, Michael; Matheus, Paul; Slatkin, Montgomery; Pollack, Joshua L.; Malaspinas, Anna-Sapfo; Rohland, Nadin (Jul 24, 2007). "Proboscidean Mitogenomics: Chronology and Mode of Elephant Evolution Using Mastodon as Outgroup". PLOS Biology. 5 (8): e207. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0050207.st004. PMC 1925134. PMID 17676977.

- Karpinski, E.; Hackenberger, D.; Zazula, G.; Widga, C.; Duggan, A.T.; Golding, G.B.; Kuch, M.; Klunk, J.; Jass, C.N.; Groves, P.; Druckenmiller, P.; Schubert, B.W.; Arroyo-Cabrales, J.; Simpson, W.F.; Hoganson, J.W.; Fisher, D.C.; Ho, S.Y.W.; MacPhee, R.D.E.; Poinar, H.N. (2020). "American mastodon mitochondrial genomes suggest multiple dispersal events in response to Pleistocene climate oscillations". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 4048. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.4048K. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-17893-z. PMC 7463256. PMID 32873779.

- Lange, I.M. (2002). Ice Age Mammals of North America: A Guide to the Big, the Hairy, and the Bizarre (illustrated ed.). Mountain Press Publishing. pp. 166–168. ISBN 0878424032.

- Woodman, N. (2008). "The Overmyer Mastodon (Mammut americanum) from Fulton County, Indiana". The American Midland Naturalist. 159 (1): 125–146. doi:10.1674/0003-0031(2008)159[125:TOMMAF]2.0.CO;2.

- Lucas, Spencer G.; Guillermo E. Alvarado (2010). "Fossil Proboscidea from the Upper Cenozoic of Central America: Taxonomy, Evolutionary and Pelobiogeographic Significance". Revista Geológica de América Central. 42: 9–42. ISSN 0256-7024.

- Sullivan, Robert M. (2010). "Rising from the muck: The Marshalls Creek mastodon". Pennsylvania Heritage.

- Sukumar, R. (September 11, 2003). The Living Elephants: Evolutionary Ecology, Behaviour, and Conservation. Oxford University Press, USA. p. 262. ISBN 978-0-19-510778-4. OCLC 935260783.

- Haynes, G.; Klimowicz, J. (2003). "Mammoth (Mammuthus spp.) and American mastodont (Mammut americanum) bonesites: what do the differences mean?". Advances in Mammoth Research. 9: 185–204.

- Chapman, J.L. and Reiss, M.J., Ecology: Principles and Applications. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1999. p. 304. (via Google books, February 25, 2008)

- Pérez-Crespo, V.A.; Prado, J.L.; Alberdi, M.T.; Arroyo-Cabrales, J.; Johnson, E. (2016). "Diet and Habitat for Six American Pleistocene Proboscidean Species Using Carbon and Oxygen Stable Isotopes". Ameghiniana. 53 (1): 39–51. doi:10.5710/AMGH.02.06.2015.2842. S2CID 87012003.

- Lepper, B. T.; Frolking, T. A.; Fisher, D. C.; Goldstein, G.; Sanger, J. E.; Wymer, D. A.; Ogden, J.G.; Hooge, P. E. (1991). "Intestinal Contents of a late Pleistocene Mastodont from Midcontinental North America" (PDF). Quaternary Research. 36 (1): 120–125. Bibcode:1991QuRes..36..120L. doi:10.1016/0033-5894(91)90020-6. hdl:2027.42/29243.

- Fisher, D. C. (1996). "Extinction of Proboscideans in North America". In Shoshani, J.; Tassy, P. (eds.). The Proboscidea: Evolution and Palaeoecology of Elephants and Their Relatives. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. pp. 296–315.

- Green, J. L.; DeSantis, L. R. G.; Smith, G. J. (2017). "Regional variation in the browsing diet of Pleistocene Mammut americanum (Mammalia, Proboscidea) as recorded by dental microwear textures". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 487: 59–70. Bibcode:2017PPP...487...59G. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2017.08.019.

- "Northborough's Mastodon". Northborough MA Letterboxing. 2007-09-15. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- "Prehistoric Massachusetts". The Paleontology Portal. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- "Cohoes Mastodon". Cohoes.com. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- "Prehistoric New York: Mastodons". Discovery Channel. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- Prado, J. L.; Alberdi, M. T.; Azanza, B.; Sánchez, B.; Frassinetti, D. (2005). "The Pleistocene Gomphotheriidae (Proboscidea) from South America". Quaternary International. 126–128: 21–30. Bibcode:2005QuInt.126...21P. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2004.04.012.

- Martin, P. S. (2005). "Chapter 6. Deadly Syncopation". Twilight of the Mammoths: Ice Age Extinctions and the Rewilding of America. University of California Press. pp. 118–128. ISBN 0-520-23141-4. OCLC 58055404. Retrieved February 1, 2016.

- Burney, D. A.; Flannery, T. F. (July 2005). "Fifty millennia of catastrophic extinctions after human contact" (PDF). Trends in Ecology & Evolution. Elsevier. 20 (7): 395–401. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.04.022. PMID 16701402. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 10, 2010. Retrieved June 12, 2009.

- Beck, Roger B.; Black, Linda; Krieger, Larry S.; Naylor, Phillip C.; Shabaka, Dahia Ibo (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, Illinois: McDougal Littell. ISBN 0-395-87274-X.

- Ward, Peter (1997). The Call of Distant Mammoths. Springer. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-387-98572-5.

- Fisher, Daniel C. (2009). "Paleobiology and Extinction of Proboscideans in the Great Lakes Region of North America". In Haynes, Gary (ed.). American Megafaunal Extinctions at the End of the Pleistocene. Springer. pp. 55–75. doi:10.1007/978-1-4020-8793-6_4. ISBN 978-1-4020-8792-9.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Mammut. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mammut. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Mastodon. |

- The Rochester Museum of Science - Expedition Earth Glaciers & Giants

- Illinois State Museum - Mastodon

- Calvin College Mastodon Page

- American Museum of Natural History - Warren Mastodon

- BBC Science and Nature:Animals - American mastodon Mammut americanum

- BBC News - Greek mastodon find 'spectacular'

- Missouri State Parks and Historic Sites - Mastodon State Historic Site

- Saint Louis Front Page - Mastodon State Historic Site

- Story of the Randolph Mastodon (Earlham College)

- The Florida Museum of Natural History Virtual Exhibit - The Aucilla River Prehistory Project:When The First Floridians Met The Last Mastodons

- Western Center for Archaeology & Paleontology, home of the largest mastodon ever found in the Western United States

- Smithsonian Magazine Features Mammoths and Mastodons

- 360 View of a Mastodon Skull from Indiana State Museum

- 3-D Viewers of male and female mastodon skeletons at the University of Michigan Mammutidae digital fossil repository