Arab Christians

Arab Christians (Arabic: ﺍﻟﻤﺴﻴﺤﻴﻮﻥ ﺍﻟﻌﺮﺏ al-Masīḥiyyūn al-ʿArab) are Arabs of the Christian faith.[10] Some are descended from ancient Arab Christian clans that did not convert to Islam, such as the Sabaean tribes of Yemen (Ghassanids, Banu Judham etc.) and the Nabataeans who settled in Transjordan and Syria. Others are descended from Arabized Christians, such as the Antiochian Greek Christians. Arab Christians are estimated to number between 520,000[1]–703,000[11] in Syria, 350,000[1] in Lebanon, 221,000 in Jordan,[2] 10,000[6]–350,000[1] in Egypt, 133,130 in Israel and 50,000 in the State of Palestine. There are also Arab Christian communities in Iraq and Turkey.

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 520,000[1]–703,000[a] excluding 35–50 thousand Maronites | |

| 350,000[1] excluding 1 million Maronites | |

| 221,000[2] | |

| 133,130[3] excluding Copts and Maronites | |

| 38,000[4]–50,000[5] excluding disputed territories | |

| 10,000[1] | |

| 10,000[6]–350,000[1][a] excluding 9-15 million Copts | |

| 18,000[7] including Antiochian Greeks | |

| 8,000 [8]–40,000.[9] including Berbers | |

| Languages | |

| Arabic, Hebrew (within Israel), French (within Lebanon and diaspora), English, Spanish and Portuguese (diaspora) | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity: Roman Catholic (Eastern, various rites and jurisdictions; Latin) Eastern Orthodox (Antioch, Jerusalem, Alexandria) Protestant | |

[a].^ prior to Syrian civil war | |

| Part of a series on |

| Arabic culture |

|---|

|

Emigrants from Arab and Arabized Christian communities make up a significant proportion of the Middle Eastern diaspora, with sizable population concentrations across the Americas, most notably in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, Venezuela, Colombia, and the US, however those emigrants in the Americas, especially from the first wave of emigration, have not passed the Arabic language nor the Arab identity to their descendants.[12]

The first Arab tribes to adopt Christianity were likely Nabataeans and Ghassanids. During the fifth and sixth centuries, the Ghassanids, who at first adopted monophysitism, formed one of the most powerful confederations allied to Christian Byzantium, being a buffer against the pagan tribes of Arabia. The last king of the Lakhmids, al-Nu'man III ibn al-Mundhir, a client of the Sasanian Empire in the late sixth century, converted to Christianity (in this case, to the Nestorian sect favoured by the native Christians of al-Hira).[13] Arab Christians have significantly influenced and contributed to the Arabic culture in many fields both historically and in modern times,[14] including Literature,[14] politics,[14] business,[14] philosophy,[15] music, theatre and cinema,[16] medicine,[17] and science.[18]

Arab Christians are not the only Christian group in the Middle East, with significant non-Arab indigenous Christian communities of Assyrians, Armenians, and others. Although sometimes classified as "Arab Christians", the largest Middle Eastern Christian groups of Maronites and Copts often claim non-Arab ethnicity: a significant proportion of Maronites claim descent from the ancient Phoenicians while a significant proportion of Copts also eschew an Arab identity, preferring an Ancient Egyptian one.[19]

History

Classic antiquity

Arab Christians are the indigenous Christian communities of Western Asia who became majority Arabic-speaking after the consequent seventh-century Muslim conquests in the Fertile Crescent.[20] The Christian Arab presence predates Muslim conquests and there were many Arab tribes which adhered to Christianity beginning in the 1st century.[21]

_and_over_4%252C000_with_him_(Menologion_of_Basil_II).jpg.webp)

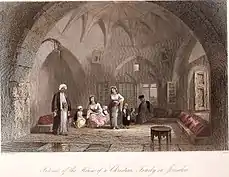

The first mention of Christianity in Arabia occurs in the New Testament as the Apostle Paul references his journey to Arabia following his conversion (Galatians 1: 15–17). Later, Eusebius discusses a bishop named Beryllus in the see of Bostra, the site of a synod c. 240 and two Councils of Arabia.[22] Scholars suggest that Philip the Arab was the first Christian emperor of Rome (244 to 249).[22] Modern scholars are divided on the issue. The Nabataeans were among the first Arab tribes to arrive in the southern Levant in the late first millennium BC. The Nabataeans initially adopted pagan beliefs, but they became Christians by the time of the Byzantine period around the 4th century.[23] Their lands were divided between the new Qahtanite Arab tribal kingdoms of the Byzantine vassals, the Ghassanids, the Himyarite Kingdom and the Kindah in North Arabia. Petra in Jordan is an ancient Nabataean city and it is considered to be a sacred site for many Arab Christians in the Levant.[24] The tribes of Tayy, Banu Abdul Qays, and Taghlib amongst others are also known to have included many Christians in the pre-Islamic period.

By the fourth century, a significant number of Christians occupied the Sinai Peninsula, Mesopotamia and the Arabian Peninsula. History also records Christian influence coming from Ethiopia to Arab lands in pre-Islamic times. Some Hejazis, including a cousin of Muhammad's wife Khadija bint Khuwaylid, may have adopted the religion, whilst some Ethiopian Christians may have lived in Mecca.[25] The southern Arabian city of Najran (in modern day Saudi Arabia), was the center of Arabian Christianity, made famous by the religious persecution by one of the kings of Yemen, Dhu Nuwas, who himself was an enthusiastic convert to Judaism. The leader of the Arabs of Najran during the period of persecution, al-Ḥārith, was canonized by the Catholic Church as Arethas. Aretas was the leader of the Christian community of Najran in the early 6th century and was executed during the persecution and massacre of Christians by the Jewish king in 523.

The New Testament has a biblical account of Arab conversion to Christianity recorded in the book of Acts. When Saint Peter preaches to the people of Jerusalem, they ask,

And how hear we every man in our own tongue, wherein we were born?

[...] Cretes and Arabians, we do hear them speak in our tongues the wonderful works of God. (Acts 2:8, 11 KJV)

Islamic era

Following the fall of large portions of former Byzantine and Sasanian provinces to the Arab armies, a large indigenous Christian population of varying ethnicities came under Arab Muslim dominance. Historically, a number of minority Christian sects were persecuted as heretic under Byzantine rule (such as non-Chalcedonians). As Muslim army commanders expanded their empire and attacked countries in Asia, North Africa and southern Europe, they would offer three conditions to their enemies: convert to Islam, or pay jizya (tax) every year, or face war to death. Those who refused war and refused to convert were deemed to have agreed to pay jizya.[26][27]

As "People of the Book", Christians in the region were accorded certain rights under Islamic law to practice their religion (including having Christian law used for rulings, settlements or sentences in court). In contrast to Muslims, who paid the zakat tax, they paid the jizya, an obligatory tax. The jizya was not levied on slaves, women, children, monks, the old, the sick, hermits, or the poor.[28] In return, non-Muslim citizens were permitted to practice their faith, to enjoy a measure of communal autonomy, to be entitled to Muslim state's protection from outside aggression, to be exempted from military service and the zakat.[29][30] Like Arab Muslims, Arab Christians refer to God as Allah, as an Arabic word for "God".[31] The use of the term Allah in Arab Christian churches predates Islam by several centuries.[31]

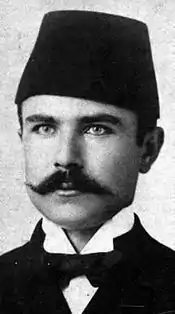

Role in al-Nahda

The Renaissance of Arab culture or al-Nahda was a cultural renaissance that began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it began in the wake of the exit of Muhammad Ali of Egypt from the Levant in 1840.[32] Beirut, Cairo, Damascus and Aleppo were the main centers of the renaissance and this led to the establishment of schools, universities, theater and printing presses. It also led to the renewal of literary, linguistic and poetic distinctiveness. The emergence of a politically active movement known as the "association" was accompanied by the birth of the idea of Arab nationalism and the demand for the reformation of the Ottoman Empire. The emergence of the idea of Arab independence and reformation led to the calling of the establishment of modern states based on the European-style.

It was during this stage that the first compound of the Arabic language was introduced along with the printing of it in Arabic letters. This led into the fields of music, sculpture, history and the humanities, as well as economics and human rights. This cultural renaissance during the late Ottoman rule was a quantum leap for them in the post-industrial revolution, and is not limited to the individual fields of cultural renaissance in the nineteenth century, as the Nahda movement only extended to include the spectrum of society and the fields as a whole. It is agreed among historians the importance of roles played by the Arab Christians in this renaissance, both in Lebanon, Egypt, Palestine, Syria, Jordan and their role in the prosperity through participation in the diaspora also.[33][14][34]

Because Arab Christians formed the educated and bourgeois classes, they had a significant impact on politics, business and culture of the Arab World.[35] Some of the most influential Arab nationalists were Arab Christians, for example, Saleem Takla and his brother Bishara Takla founded the Al-Ahram newspaper in 1875 in Egypt and it is now the most widely circulated Egyptian daily newspaper and second oldest.[36] Christian colleges like Saint Joseph University and the American University of Beirut thrived in Lebanon, Al-Hikma University in Baghdad and others played leading role in the development of civilization and Arab culture.[37]

Given this growing Christian role in politics and culture, Ottoman ministers began to have Arab Christians in their governments. In the economic sphere, a number of Christian families such as the Sursock became prominent. Thus, the Nahda led the Muslims and Christians to a cultural renaissance and national general despotism. This established the renaissance and solidified Arab Christians as one of the pillars of the region and not as a minority on the fringes.[38]

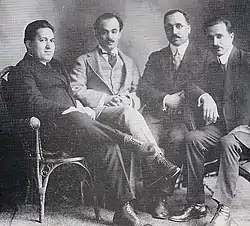

Role in al-Mahjar

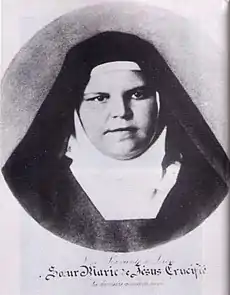

The Mahjar (one of its more literal meanings being "the Arab diaspora") was a literary movement that succeeded the Nahda movement. It was started by Christian Arabic-speaking writers who had emigrated to America from Ottoman-ruled Lebanon, Syria and Palestine at the turn of the 20th century. These writers, in South America as well as the United States, contributed to the further development of the Nahda in the early 20th century. Kahlil Gibran is considered to have been the most influential of the "Mahjar poets" or "Mahjari poets". The writers of the Mahjar movement were stimulated by their personal encounter with the Western world and participated in the renewal of Arabic literature, hence their proponents being sometimes referred to as writers of the "late Nahda".

The Pen League was the first Arabic-language literary society in North America, formed initially by Nasib Arida and Abd al-Masih Haddad. Members of the Pen League included: Nasib Arida, Rashid Ayyub, Wadi Bahout, William Catzeflis, Kahlil Gibran, Abd al-Masih Haddad, Nadra Haddad, Elia Abu Madi, Mikhail Naimy, and Ameen Rihani.[39] Eight out of the ten members were Greek Orthodox and two were Maronite Christians. The league dissolved following Gibran's death in 1931 and Mikhail Naimy's return to Lebanon in 1932.[40]

Abraham Mitrie Rihbany was a Lebanese-American Intellectual of the Mahjar movement. His best-known book, The Syrian Christ (1916), was highly influential in its time in explaining the cultural background to some situations and modes of expression found in the Gospels.

Modern era

It is a common agreement that after the rapid expansion of Islam from the 7th century onward, many Christians chose not to convert to Islam. Many scholars and intellectuals like Edward Said believe Christians in the Arab world have made significant contributions to the Arab civilization since the introduction of Islam. Some of the top poets at certain times were Arab Christians, and many Arab Christians were and are physicians, writers, government officials, and people of literature. Arab Christians formed the educated upper class, and they have had a significant impact in politics, business and culture of the Arab world.[14][35] Due to the geopolitical situations of the host countries, Arab Christians today remain politically moderate, highly educated and relatively wealthy.[41] In recent times (especially since the mid-19th century), some Arab Christian families have been converted from native, traditional churches to more recent Protestant ones, most notably Baptist and Methodist churches. This is mostly due to an influx of Western missionaries.[42]

Arab Christians have always been the go-between the Islamic world and the Christian West, mainly down to shared religious affinity. The Greek Orthodox share Orthodox ties with Russia, Romania, Bulgaria, Serbia and Greece; whilst Melkites and Maronites share Catholic bonds with Italy, Vatican, France and wider Syriac Christendom.[41] In Lebanon, Maronite Christians and Greek Catholics looked to France and the Mediterranean world, whereas most Muslims and Orthodox Christians looked to the Arab hinterland as their political lodestar.[43] As a result of colonial times, French forenames became popular with the Syrian and Lebanese Christians. Popular names included Michel, Pierre and Camille.

Since antiquity, there has always been a Levantine presence in Egypt, however they started becoming a distinctive minority in Egypt around the early 18th century. The Syro-Lebanese Christians of Egypt were highly influenced by European culture and established churches, printing houses and businesses across Egypt. Their aggregate wealth was reckoned at one and a half billion francs, 10% of the Egyptian GDP at the end of the 20th century. They took advantage of the Egyptian constitution that established the juridical equality of all citizens and granted the Christians the fullness of civil rights, prior to the Nasser reforms.[44] The Lebanese diaspora in Egypt funded the shipping of food supplies to Mount Lebanon during the Great Famine, sent via the Syrian Island town of Arwad.[45]

Religious persecution

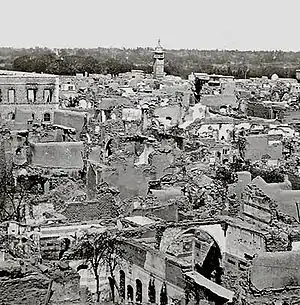

The Massacre of Aleppo of 1850 often referred to simply as The Events was a riot perpetrated by Muslim residents of Aleppo, largely from the eastern quarters of the city, against Christian residents, largely located in the northern suburbs of Judayde (Jdeideh) and Salibeh. The Events are considered by historians to be particularly important in Aleppian history, for they represent the first time disturbances pitted Muslims against Christians in the region. The patriarch of the Syriac Catholic Church Peter VII Jarweh was fatally wounded in the attacks and died a year later. 20-70 people died from rioting and 5,000 died as a result of bombardment.

1860 Mount Lebanon civil war was a civil conflict in Mount Lebanon during Ottoman rule in 1860-1861 fought mainly between the local Druze and Maronite Christians. Following decisive Druze victories and massacres against the Christians, the conflict spilled over into other parts of Ottoman Syria, particularly Damascus, where thousands of Christian residents were killed by Muslim and Druze militiamen. With the connivance of the military authorities and Turkish soldiers, Druze and Sunni Muslim paramilitary groups organised pogroms in Damascus which lasted three days (9-11 July).[46] By the war's end, around 20,000 people, mainly Catholic Christians, had been killed in Mount Lebanon and Damascus, and 380 Christian villages and 560 churches were destroyed. Churches and missionary schools were set on fire. The Druze and Muslims also suffered heavy losses.[47] The Christian inhabitants of the notoriously poor and refractory al-Midan district outside the walls of Damascus (mostly Orthodox) were, however, protected by their Muslim neighbors. Many Christians were saved through the intervention of the Muslim Algerian exile Emir Abdelkader and his soldiers, who brought them to safety in Abdelkader's residence and the Citadel of Damascus. This 1860 conflict led France to intervene and stop the massacre of Christian civilians after Ottoman troops had been aiding Islamic forces by either direct support or by disarming Christian forces. France, led by Napoleon III, recalled its ancient role as protector of Christians in the Ottoman Empire which was established in a treaty in 1523.[48] Following the massacre, the Ottoman Empire agreed to dispatch up to 12,000 European soldiers to reestablish order.

Melkite Greek Catholic and Maronite Christians suffered a religiously-motivated Genocide at the hands of the Ottomans and their allies during the Great Famine of Mount Lebanon during World War I, which ran in conjunction with the Assyrian genocide, the Armenian Genocide and the Greek genocide. The Mount Lebanon famine caused the highest fatality rate by population during World War I.[49] Around 200,000 people starved to death when the population of Mount Lebanon was estimated to be 400,000 people.[50] On 26 May 1916, Gibran Khalil Gibran wrote a letter to Mary Haskell that reads: "The famine in Mount Lebanon has been planned and instigated by the Turkish government. Already 80,000 have succumbed to starvation and thousands are dying every single day. The same process happened with the Christian Armenians and applied to the Christians in Mount Lebanon."[51]

Significant persecution and displacement of Iraqi Christians in Mosul and other areas held by ISIS, including Syria, occurred from 2014 onwards, with Christian houses identified with the Arabic letter "N" for "Nasrani" (Christian).[52]

Regional conflicts

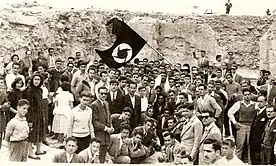

During the 1948 Arab–Israeli War, a number of Palestinian Arab Greek Orthodox communities were ethnically cleansed and driven out of their towns, including al-Bassa, Ramla, Lod, Safed, Kafr Bir'im, Iqrit, Tarbikha, Eilabun and 20,000 Christians fled Haifa. In addition, around 20,000 fled West Jerusalem, 700 fled Acre and 10,000 fled Jaffa. Many Christian towns or neighborhoods were totally or partially ethnically cleansed and destroyed during the period between 1948 and 1953. All the Christian residents of Safed, Beisan, Tiberias were removed, and a big percentage displaced in Haifa, Jaffa, Lydda and Ramleh. Prominent Christians remained such as Tawfik Toubi, Emile Touma and Emile Habibi and they went on to be leaders of the Palestinian Communist party in Israel. George Habash, founder of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine was an Arab Christian. Wadie Haddad was the leader of the PFLP's armed wing. Many Palestinian Christians were also active in the formation and governing of the Palestinian National Authority since 1994. Arab Christian Constantin Zureiq was the first to coin the term "Nakba" in reference to the 1948 Palestinian exodus.

In 1975, the Lebanese Civil War occurred between two broad camps, the mainly Christian 'rightist' Lebanese Front consisting of Maronite and Melkites, and the mainly Muslim and Arab nationalist 'leftist' National Movement, supported by the Druze, Greek Orthodox and Palestinian community. The war was characterized by the kidnap, rape and massacre of those caught in the wrong place as each side eliminated 'enemy' enclaves - mainly Christian or Muslim low-income areas.[53] In 1982 Israel invaded Lebanon with the aim of destroying the PLO, which it besieged in West Beirut. Israel was later obliged to withdraw as a result of multiple guerrilla attacks by the Lebanese National Resistance Front and increasing hostility across Lebanon to their presence.[53] Greek Orthodox-born SSNP member Sana'a Mehaidli is believed to be the first female suicide bomber. She is known in Lebanon as the "Bride of the South" and martyred herself in Jezzine during the Israeli occupation of South Lebanon.

With the events of the Arab Spring, the Syrian Arab Christian community was heavily hit in line with other Christian communities of Syria, being victimized by the war and specifically targeted as a minority by Jihadist forces. Many Christians, including Arab Christians, were displaced or fled Syria over the course of the Syrian Civil War, however some stayed and continue to fight with the Syrian Armed Forces and the allied Eagles of the Whirlwind (armed wing of the SSNP) against insurgents today. When the conflict in Syria began, it was reported that Christians were cautious and tried to avoid taking sides, but that due to the increased violence in Syria and the IS's growth, Arab Christians have shown support for Assad, fearing that if Assad is overthrown, they will be targeted. Christians support the Assad regime based on fear that the end of the current government could lead to instability. The Carnegie Middle East Center similarly stated that the majority of Christians are more in support of the regime because they fear a chaotic situation or to be under the control of the Islamic, and so called 'secular' Western and Turkish backed armed groups.[54][55]

Legacy

Some of the most influential Arab nationalists were Greek Orthodox Christians, like the Syrian intellectual Constantin Zureiq, the influential ba'athism proponent Michel Aflaq and Jurji Zaydan, who was reputed to be the first Arab nationalist. Several Arab Palestinian Christians edited and owned the leading newspapers in Mandatory Palestine including Falastin, edited by cousins Issa El-Issa and Yousef El-Issa, and Al-Karmil, which was edited by Najib Nassar. Khalil al-Sakakini, a prominent Jerusalemite, was also an Arab Orthodox, as was George Antonius, author of The Arab Awakening.

The first Syrian nationalists were also Christian. Greek Orthodox Antoun Saadeh was the founder behind the secular Syrian Social Nationalist Party (SSNP) and Butrus al-Bustani, a Maronite convert to Protestantism, is considered to be the first Syrian nationalist. Sa'adeh rejected Arab Nationalism (the idea that the speakers of the Arabic language form a single, unified nation), and argued instead for the creation of a "United Syrian Nation" or "Natural Syria".

Greek Orthodox Charles Debbas was the first President of Lebanon (before independence) and served from 1926 till 1934, under the French Mandate of Lebanon (known as Greater Lebanon). Fares al-Khoury was the twice prime minister of Syria and "godfather of modern Syrian politics". Faris Koury's position as prime minister is, as of 2021, the highest political position a Christian has ever reached in Syria. Fares was born into a Greek Orthodox Christian family that converted to Presbyterianism. Other prominent politicians include: Rajai Muasher, Dawoud Abdallah Rajiha, Afif Safieh, Mounir Abou Fadel, Gebran Tueni, Hanan Ashrawi, Ayoub Tabet and Charbel Nahas. In accordance with the National Pact, the President of Lebanon must be a Maronite Christian, the Deputy Speaker of the Parliament a Greek Orthodox Christian and Melkites and Protestants have nine reserved seats in the Parliament of Lebanon.

Mikhail Mishaqa converted from the Greek Catholic Church to Protestantism and was born in Rashmayyā, Lebanon. He is reputed to be the first historian of modern Ottoman Syria as well as the "virtual founder of the twenty-four equal quarter tone scale". Other academics include the essayist and scholar Nassim Nicholas Taleb, intellectual Edward Said and Nobel Prize winners Elias James Corey and Peter Medawar. Syrian writer Qustaki al-Himsi is considered to be the founder of modern literary criticism among the Arab scholars.

Some of the best selling artists in the Arab world are Christian. Notable Christian Arabs in entertainment include Lebanese singers Lydia Canaan, Fares Karam, Nancy Ajram, Fairuz and Julia Boutros. Syrian singers include Nassif Zeytoun and George Wassouf. Notable Maronite Christians include Sabah, Elissa and Wael Kfoury.

The founder and subsequent editors of the Lebanese An-Nahar newspaper belong to the Tueni family. The Tueni family is one of the original Greek Orthodox aristocratic “Seven Families” of Beirut, along with the Bustros, Fayad, Araman, Sursock, Fernaine, and Trad families, who constituted the traditional high society of Beirut. The land formerly owned by the 7 Families was concentrated in the district of Beirut known as Achrafieh. Under the French Mandate, the land was partitioned to build roads and highways during the 1930s, and eventually, the families were forced to sell vast amounts of their land.[56]

Demographics

Iraq

Christianity has a presence in Iraq dating to the first century, and Syriac Christianity, the Syriac language and Syriac alphabet evolved in Assyria in northern Iraq. The Arab Christian community in Iraq is relatively small, and further dwindled due to the Iraq War to just several thousand. Most Arab Christians in Iraq belong traditionally to Greek Orthodox and Catholic Churches and are concentrated in major cities such as Baghdad, Basra and Mosul.

The vast majority of the remaining 450,000 to 900,000 Christians in Iraq are Assyrian people, who follow Syriac Christianity, most notably the Chaldean Catholic Church, Assyrian Church of the East, Ancient Church of the East, Syriac Orthodox Church, Assyrian Evangelical Church and Assyrian Pentecostal Church.[57] More than two-thirds of Iraqi Christians have fled or immigrated to other countries. In the 1987 Iraq census there were 1.4 million Christians in a population of 22 million but the numbers had fallen to 800–900,000 by the outbreak of the 2003 war due to emigration.

Israel

In December 2009, 122,000 Arab Christians lived in Israel, as Arab citizens of Israel, out of a total of 151,700 Christian citizens.[58] According to the Central Bureau of Statistics, on the eve of Christmas 2013, there were approximately 161,000 Christians in Israel, about 2 percent of the general population in Israel. 80% of the Christians are Arab[59] with smaller Christian communities of ethnic Russians, Greeks, Armenians, Maronites, Ukrainians and Assyrians.[60]

As of 2014 the Melkite Greek Catholic Church was the largest Christian community in Israel, where about 60% of Israeli Christians belonged to the Melkite Greek Catholic Church,[61] while around 30% of Israeli Christians belonged to the Greek Orthodox Church of Jerusalem.[61] Other denominations are the Anglicans who have their cathedral church in East Jerusalem. Baptists in Israel are concentrated in the north of the country and have four churches in the Nazareth area, and a seminary. The cities and communities where most of Christians in Israel reside are Haifa, Nazareth, Jish, Mi'ilya, Fassuta and Kafr Yasif.[62]

Arab Christians are one of the most educated groups in Israel. Maariv has described the Christian Arabs sectors as "the most successful in education system".[63] Statistically, Christian Arabs in Israel have the highest rates of educational attainment among all religious communities, according to a data by Israel Central Bureau of Statistics in 2010, 63% of Israeli Christian Arabs have had college or postgraduate education, the highest of any religious and ethno-religious group.[64] Christian Arabs also have one of the highest rates of success in the matriculation examinations per capita, (73.9%) in 2016 both in comparison to the Muslims and the Druze and in comparison to all students in the Jewish education system as a group, Arab Christians were also the vanguard in terms of eligibility for higher education.[65][66][67] and they have attained a bachelor's degree and academic degree more than Jewish, Muslims and Druze per capita.[65] The rate of students studying in the field of medicine was also higher among the Christian Arab students, compared with all the students from other sectors.[65] despite the fact that Arab Christians only represent 2.1% of the total Israeli population,[68] in 2014 they accounted for 17.0% of the country's university students, and for 14.4% of its college students.[69]

Socio-economically, Arab Christians are closer to the Jewish population than to the Muslim population.[70] They have the lowest incidence of poverty and the lowest percentage of unemployment which is 4.9% compared to 6.5% among Jewish men and women.[71] They have also the highest median household income among Arab citizens of Israel and second highest median household income among the Israeli ethno-religious groups.[72] Among Arab Christians in Israel, some emphasize pan-Arabism, whilst a small minority enlists in the Israel Defense Forces.[73][74]

Jordan

Jordan contains some of the oldest Christian communities in the world, their presence dating back to the first century AD. Today, Christians today make up about 4% of the population, down from 20% in 1930.[76] This is due to high immigration rates of Muslims into Jordan, higher emigration rates of Christians to the west and higher birth rates for Muslims.[77]

Christians in Jordan are exceptionally well integrated in the Jordanian society and enjoy a high level of freedom.[78] Christians are allotted nine out of a total of 130 seats in the Parliament of Jordan, and also hold important ministerial portfolios, ambassadorial appointments, and positions of high military rank. All Christian religious ceremonies are publicly celebrated in Jordan.[79]

Jordanian Arab Christians (some have Palestinian roots since 1948) number around 221,000, according to a 2014 estimate by the Orthodox Church. The study excluded minority Christian groups and the thousands of western, Iraqi and Syrian Christians residing in Jordan.[2] Another estimate suggests the Orthodox number 125–300,000, Catholics at 114,000 and Protestants at 30,000 for a total 270–450,000. Most native Christians in Jordan identify themselves as Arab, though there are also significant Assyrian and Armenian populations in the country. There has also been an influx of Christian refugees escaping Daesh, mainly from Mosul, Iraq, numbering about 7000[80] and 20,000 from Syria.[81]

King Abdullah II of Jordan has made firm statements about Arab Christians:

Let me say once again: Arab Christians are an integral part of my region’s past, present, and future.[82]

Religious conversion of a Muslim to another religion is technically not permitted. Christian ex-Muslims are not permitted to legally convert and do not enjoy the same rights as other Christians in Jordan. However, there are cases in which a Muslim will adopt the Christian faith, secretly declaring his/her faith. In effect, they are practicing Christians, but legally Muslims; thus, the statistics of Jordanian Christians does not include Muslim converts to Christianity. A 2015 study estimates some 6500 practicing Christians from a Muslim background in Jordan.[42]

Lebanon

Lebanon holds the largest number of Christians in the Arab world proportionally and falls just behind Egypt in absolute numbers. About 350,000 of Christians in Lebanon are Orthodox and Melkites, while the most dominant group are Maronites with about 1 million population, whose Arab identity is somewhat disputed.[83]

Christians formed about 60% of Lebanese citizens after 1920.[84] The exact number of Christians in modern Lebanon is uncertain because no official census has been made in Lebanon since 1932. Lebanese Christians belong mostly to the Maronite and Greek Orthodox Churches, with sizable minorities belonging to the Melkite Greek Catholic Church and Armenian Apostolic Church. The community of Armenians in Lebanon is the most politically and demographically significant in the Middle East. Lebanese Christians are the only Christians in the Middle East with a sizable political role in the country. The Lebanese constitution requires that the Lebanese president, half of the cabinet, and half of the parliament follow one of the various Lebanese Christian rites.

While most Maronites claim pre-Arab origins in the region, with relation to Mardaites and perhaps even Phoenicians of the ancient times, there is no question Arabization of this population took place over centuries of Muslim rule and Arab domination in the region. The indigenous Western Aramaic language among the Maronites was abandoned as a spoken tongue by the end of the Middle Ages, making this community also to adopt elements of Arab culture from their Arab Christian and Arab Muslim neighbors. Nevertheless, most Maronites still strongly point out their unique origins, separate from Arab peoples, and predating the Arab migrations to the region. Some Maronites tend to oppose such divergence opinions, and actually see themselves as part of the Arab nation, defined by the Pan-Arab identity.

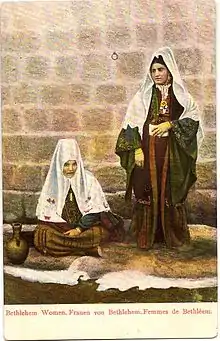

State of Palestine

Most of the Palestinian Christians claim descent from the first Christian converts, Arameans, Ghassanid Arabs and Greeks who settled in the region. Between 36,000 and 50,000 Christians live in Palestine, most of whom belong to the Orthodox (Including Greek, Syriac and Armenian Orthodox), Catholic (Roman and Melchite) churches and Evangelical communities. The majority of Palestinian Christians live in the Bethlehem and Ramallah areas with a less number in other places.[85] Many Palestinian Christians hold high-ranking positions in Palestinian society, particularly at the political and social levels. They manage the high ranking schools, universities, cultural centers and hospitals.

Christian communities in the Palestinian Authority and the Gaza Strip have greatly dwindled over the last two decades. The causes of the Palestinian Christian exodus are widely debated and it started since the Ottoman times.[86] Reuters reports that many Palestinian Christians emigrate in pursuit of better living standards,[85] while the BBC also blames the economic decline in the Palestinian Authority as well as pressure from the security situation upon their lifestyle.[87] The Vatican and the Catholic Church saw the Israeli occupation and the general conflict in the Holy Land as the principal reasons for the Christian exodus from the territories.[88]

The decline of the Christian community in Palestine follows the trend of Christian emigration from the Muslim dominated Middle East. Some churches have attempted to ameliorate the rate of emigration of young Christians by building subsidized housing for them and expanding efforts at job training.[89] The West Bank barrier and restrictions on Palestinian movement were cited by the former Israeli Ministry of Religious Affairs' chief liaison to Christians as the primary issues facing local Christians.

Gaza Strip

In 2007, just before the Hamas takeover of Gaza, there were 3,200 Christians living in the Gaza Strip.[90] Half the Christian community in Gaza fled to the West Bank and abroad after the Hamas take-over in 2007.[91]

Syria

In Syria, according to the 1960 census which recorded just over 4.5 million inhabitants, Christians formed just under 15% of the population (or 675,000). This represents a decline from 20% in 1937 when the population was 335,000. The combined population of Syrian and Lebanon in 1910 was estimated at 30% in a population of 3.5 million. Since 1960 the population of Syria has increased five-fold, but the Christian population only 3.5 times. Due to political reasons, no newer census has been taken since. Most recent estimates prior to the Syrian civil war suggested that overall Christians comprised about 10% of the overall population of Syrian 23 million citizens, due to having lower birth rates and higher emigration rates than their Muslim compatriots.[92]

Today, a sizeable share of Syrian Christians hold on to their ethnic Antiochian Greek, Assyrians (particularly in the northeast), and Armenian origins, with a major recent influx of Assyrian Iraqi Christian refugees into these communities after massacres in Turkey and Iraq during and after WWI and then post-2003. Due to the Syrian civil war, a large number of Christians fled the country to Lebanon, Jordan, and Europe, though the major share of the population still resides in Syria (some being internally displaced).

The Arab Christians of Syria are Greek Orthodox and Greek Catholic (Melkites) as well as some Latin Rite Roman Catholics. Non-Arab Syrian Christians include Assyrians (mainly in the northeast), Syriac-Arameans, Greeks and Armenians. The largest Christian denomination in Syria is the Greek Orthodox church,[93] most of whom are Arab Christians, followed in second place by the Syriac Orthodox, many of whose followers espouse an Aramean or Assyrian identity.

The appellation "Greek" refers to the liturgy Orthodox and Catholic Christians use. Sometimes it is used to refer to the ancestry and ethnicity of the members, however not all members are of Antiochian ancestry; in fact, the Arabic word used is "Rum", which means "Byzantines", or Eastern Romans. Greeks in Syria constitute a distinct separate ethnicity, numbering 4,500 in Syria today. Overall, the term is generally used to refer to the Greek liturgy. Melkite Church is another major religious denomination of Arabized Christians in Syria. Melkites, the followers of the Greek Catholic Church form another major group.

Though religious freedom is allowed in the Syrian Arab Republic, all citizens of Syria including Christians, are subject to the Shari'a-based personal status laws regulating child custody, inheritance, and adoption.[93] For example, in the case of divorce, a woman loses the right to custody of her sons when they reach the age of thirteen and her daughters when they reach the age of fifteen, regardless of religion.[93]

Turkey

Antiochian Greeks who mostly live in Hatay Province, are one of the Arabic-speaking communities in Turkey, their number approximately 18,000.[94] They are Greek Orthodox. However, they are sometimes known as Arab Christians, primarily because of their language. Antioch (capital of Hatay Province) is also the historical capital of Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch. Turkey is also home to a number of non-Arab Armenians (who number around 70,000),[95] Greeks (who number around 5,000 not including Antiochian Greeks) and Assyrian Christians in the southeast. The village of Tokaçlı in Altınözü District has an entirely Arab Christian population and is one of the few Christian villages in Turkey.[96]

Arabian Peninsula

Kuwait's native Christian population exists, though is essentially small. There are between 259 and 400 Christian Kuwaiti citizens.[98] Christian Kuwaitis can be divided into two groups. The first group includes the earliest Kuwaiti Christians, who originated from Iraq and Turkey.[99] They have assimilated into Kuwaiti society, like their Muslim counterparts, and tend to speak Arabic with a Kuwaiti dialect; their food and culture are also predominantly Kuwaiti. They makeup roughly a quarter of Kuwait's Christian population. The rest (roughly three-quarters) of Christian Kuwaitis make up the second group. They are more recent arrivals in the 1950s and 1960s, mostly Kuwaitis of Palestinian ancestry who were forced out of Palestine after 1948.[99] There are also smaller numbers who originally hail from Syria and Lebanon.[99] This second group is not as assimilated as the first group, as their food, culture, and Arabic dialect still retain a Levant feel. However, they are just as patriotic as the former group, and tend to be proud of their adopted homeland, with many serving in the army, police, civil, and foreign service. Most of Kuwait's citizen Christians belong to 12 large families, with the Shammas (from Turkey) and the Shuhaibar (from Palestine) families being some of the more prominent ones.[99]

Native Christians who hold Bahraini citizenship number approximately 1,000 persons.[100] The majority of Christians are originally from Iraq, Palestine and Jordan, with a small minority having lived in Bahrain for many centuries; the majority have been living as Bahraini citizens for less than a century. There are also smaller numbers of native Christians who originally hail from Lebanon, Syria, and India. The majority of Christian Bahraini citizens tend to be Orthodox Christians, with the largest church by membership being the Greek Orthodox Church. They enjoy many equal religious and social freedom. Bahrain has Christian members in the Bahraini government.

North Africa

There are tiny communities of Roman Catholics in Tunisia, Algeria, Libya, and Morocco due to colonial rule - French rule for Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco, Spanish rule for Morocco and Western Sahara, and Italian rule for Libya. Most Christians in North Africa are foreign missionaries, immigrant workers, and people of French, Spanish, and Italian colonial descent. The North African Christians of Berber or Arab descent mostly converted during the modern era or under and after French colonialism.[101][102]

Arguably, many more Maghrebi Christians of Arab or Berber descent live in France than in North Africa, due to the exodus of the pieds-noirs in the 1960s. Charles de Foucauld was renowned for his missions in North Africa among Muslims, including African Arabs. Today conversions to Christianity have been most common in Algeria,[103] especially in the Kabylie, and Morocco[104] and Tunisia.[105] A 2015 study estimates 380,000 Muslims converted to Christianity in Algeria.[42] While it's estimated that between 8,000[106]-40,000[107] Moroccans converted to Christianity in the last decades; although some estimate the number to be as high as 150,000.[108] In Tunisia, however, the number of Tunisian Christians is estimated to be around 23,500.[109]

Egypt

If one excludes the Copts who adhere to an Ancient Egyptian heritage, the numbers of the Greek Orthodox Church adherents in Egypt, who are ethnically Greek and possibly Arab, is rather small - on the order of several thousand each. There are several isolated Greek Orthodox communities, largely composed of Arabs, in the Sinai Peninsula, though the rest of Egypt also has tiny numbers of other than Copts minorities.

Most Egyptian Christians are Copts, who are mainly members of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria. Although Copts in Egypt speak Egyptian Arabic, many of them do not consider themselves to be ethnically Arabs, but rather descendants of the ancient Egyptians. The Copts constitute the largest population of Christians in the Middle East, numbering between 8,000,000 and 15,000,000. The liturgical language of the Copts, the Coptic language, is a direct descendant of the Egyptian language. Coptic remains the liturgical language of all Coptic churches.

Diaspora

Millions of Arab Christians also live in the diaspora, outside of the Middle East. They reside mainly in the Americas. There are also many Arab Christians in Europe, especially in France (due to its historical connections with Lebanon and North Africa), Spain (due to its historical connections with northern Morocco), and to a lesser extent, Ireland, Sweden, United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, Greece and the Netherlands. Among those and across the Americas, an estimated million Palestinian Christians are living in the Palestinian diaspora.

Affiliated communities

The Arab Christians largely belong to the Greek Orthodox Church of Jerusalem or Antiochian Eastern-Orthodox and Antiochian Oriental-Orthodox Churches, though there are also adherents to other churches: Melkite Greek Catholic Church, Latin Catholic Church and Protestant Churches.

Melkites

Arabized Melkite societies in Lebanon, Syria, Israel, and Palestine, trace their roots to Greek and Aramaic-speaking Byzantine Christians. They are also generally included under the definition of Arab Christians, although this label is not universally accepted by all.

Greek Orthodox

Greek Orthodox or Eastern Orthodox, also known as Rûm, Orthodox Christian communities, part of the Rūm Millet, which have existed in Southern Anatolia (Turkey) and Syrian region since the early years of Christianity: they are generally affiliated along geographic lines either to the Antiochian ("Northern") or Jerusalemite ("Southern") patriarchal jurisdictions.

There have been numerous disputes between the Arab and the Greek leadership of the church in Jerusalem from the Mandate onwards. Jordan encouraged the Greeks to open the Brotherhood to Arab members of the community between 1948 and 1967 when the West Bank was under Jordanian rule. Land and political disputes have also been common since 1967, with the Greek priests portrayed as collaborators with Israel. Land disputes include the sale of St. John's property in the Christian quarter on 11 April 1990, the transfer of fifty dunams near Mar Elias monastery, and the sale of two hotels and twenty-seven stores on Omar Bin Al-Khattab square near the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. A dispute between the Palestinian Authority and the Greek Patriarch Irenaios led to the Patriarch being pushed aside because of accusations of a real estate deal with Israel. The Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem is an autocephalous Orthodox Church within the wider communion of Orthodox Christianity. The Arab Orthodox Society exists in Jerusalem and is one of the oldest and the largest is the Arab Orthodox Benevolent Society in Beit Jala, Palestine.

Greek Orthodox Church of Alexandria is an autocephalous Byzantine Rite jurisdiction of the Eastern Orthodox Church, having the African continent as its canonical territory. It is commonly called the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Alexandria to distinguish it from the Oriental Orthodox Coptic Orthodox Patriarchate of Alexandria. Members of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate were once known as Melkites because they remained in communion with the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople after the schism that followed the Council of Chalcedon in 451. The Orthodox Christian community of Egypt is thus unaffiliated with Copts and does mostly adhere to an Arab identity.

Rum Christians

Many members of the Northern Antiochian communities still call themselves Rûm which literally means "Roman", or "Asian Greek" in Turkish, Persian and Arabic. In that particular context, the term "Rûm" is used in preference to "Yāvāni" or "Ionani" which means "European-Greek" or Ionian in Biblical Hebrew (borrowed from Old Persian Yavan = Greece) and Classical Arabic. Some members of the community also call themselves "Melkites", which literally means "monarchists" or "supporters of the emperor" in Semitic languages (a reference to their past allegiance to Macedonian and Roman imperial rule), but, in the modern era, that term tends to be more commonly used by followers of the Greek Catholic church.

Question of identity

Arab Christians include descendants of ancient Arab tribes, who were among the first Christian converts, as well as some recent adherents of Christianity. Sometimes, however, the issue of self-identification arises regarding specific Christian communities across the Arab world.

Assyrians

The Assyrians form the majority of Christians in Iraq, northeast Syria, south-east Turkey and north-west Iran. They are specifically defined as non-Arab indigenous ethnic group, including by the governments of Iraq, Lebanon, Iran, Syria, Israel, and Turkey. Assyrians practice their own native dialects of Syriac-Aramaic language, in addition to also sometimes speaking local Arabic, Turkish or Farsi dialects. Despite their ancient pre-Arabic roots and distinct lingo-cultural identities, Assyrians are sometimes erroneously referred by Western sources as "Christians of the Arab World" or "Arabic Christians", creating confusion about their identity.[110] Assyrians were also wrongly related as "Arab Christians" by pan-Arabist movements and Arab-Islamic regimes.[10][111] They likewise pointed out that Arab nationalist groups have wrongly included Assyrian-Americans in their headcount of Arab Americans, in order to bolster their political clout in Washington. Some Arab American groups have imported this denial of Assyrian identity to the United States. In 2001, a coalition of Assyrian-Chaldean and Maronite church organizations, wrote to the Arab-American Institute, to reprimand them for claiming that Assyrians were Arabs. They asked the Arab-American Institute "to cease and desist from portraying Assyrians and Maronites of past and present as Arabs, and from speaking on behalf of Assyrians and Maronites."[112][113]

Copts

The Copts are the native Egyptian Christians, a major ethnoreligious group in Egypt. Christianity was the majority religion in Roman Egypt during the 4th to 6th centuries and until the Muslim conquest[114] and remains the faith of a significant minority population. Their Coptic language is the direct descendant of the Demotic Egyptian spoken in the Roman era, but it has been near-extinct and mostly limited to liturgical use since the 18th century. Copts in Egypt constitute the largest Christian community in the Middle East, as well as the largest religious minority in the region, accounting for an estimated 10% of Egyptian population.[115] Most Copts adhere to the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria.[116] The remaining (around 800,000) are divided between the Coptic Catholic and various Coptic Protestant churches. As a religious minority, the Copts are subject to significant discrimination in modern Egypt, and the target of attacks by militant Islamic extremist groups.

Maronites

In post civil-war Lebanon, since the Taif Agreement, politically Phoenicianism, as an alternate to Arabism, has been restricted to a small group.[117] Phoeniciansm is deeply disputed by some scholars, who have on occasion tried to convince these claims are false and to embrace and accept the Arab identity instead.[118][119] This conflict of ideas of an identity is believed to be one of the main pivotal disputes between the Muslim and Maronite Christian populations of Lebanon and what mainly divides the country from national unity.[120] It's generalized that Muslims focus more on the Arab identity of Lebanese history and culture whereas Christians focus on the pre-arabized & non-Arab spectrum of the Lebanese identity and rather refrain from the Arab specification.[121]

Aramean identity

In contrast to most Arab Christians in Israel, a handful of Arabic-speaking Christian Israelis do not consider themselves Arab, noting their non-Arab, Aramean ancestry as a source. This is especially evident in the Maronite-dominated city of Jish in Galilee, where Aramean nationalists have been trying to resurrect Aramaic as a spoken language. In September 2014, Israel recognized the "Aramean" ethnic identity, in which Arabic-speaking Christians of Israel, with Aramean affinity, can now register as "Aramean" rather than Arab.[122] The Aramean ethnic identity can be given to Aramaic-speaking adherents of five Christian Eastern Syriac churches in Israel, including the Maronite Church, Greek Orthodox Church, Greek Catholic Church, Syriac Catholic Church and Syrian Orthodox.[123]

See also

References

- "Christians of the Middle East - Country by Country Facts and Figures on Christians of the Middle East". Middleeast.about.com. 9 May 2009. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- Kildani, Hanna (8 July 2015). "The percentage of Jordanian Christians residing is 3.68%" الأب د. حنا كلداني: نسبة الأردنيين المسيحيين المقيمين 3.68% (in Arabic). Abouna.org. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- "CBS data on Christian population in Israel (2016)" (in Hebrew). Cbs.gov.il.

- "The Beleaguered Christians of the Palestinian-Controlled Areas, by David Raab". Jcpa.org. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- Chehata, Hanan (22 March 2016). "The plight and flight of Palestinian Christians" (PDF). Middle East Monitor. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 June 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- "Who are Egypt's Christians?". BBC News. 26 February 2000.

- Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. "Christen in der islamischen Welt". Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- "Christian Converts in Morocco Fear Fatwa Calling for Their Execution". Christianity Today. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- "'House-Churches' and Silent Masses —The Converted Christians of Morocco Are Praying in Secret". Vice. 23 March 2015. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- Phares, Walid (2001). "Arab Christians: An Introduction". Arabic Bible Outreach Ministry. Archived from the original on 5 November 2004.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- "Overview of religious history of Syria". ewtn.org. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- "Demographics". Arab American Institute. Archived from the original on 23 October 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- Philip K. Hitti. History of the Arabs. 6th ed.; Macmillan and St. Martin's Press, 1967, pp. 78–84 (on the Ghassanids and Lakhmids) and pp. 87–108 (on Yemen and the Hijaz).

- Pacini, Andrea (1998). Christian Communities in the Arab Middle East: The Challenge of the Future. Clarendon Press. pp. 38, 55. ISBN 978-0-19-829388-0.

- C. Ellis, Kail (2004). Nostra Aetate, Non-Christian Religions, and Interfaith Relations. Springer Nature. p. 172. ISBN 9783030540081.

- Hourani, Albert (1983) [First published 1962]. Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age, 1798–1939 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27423-4.

- Prioreschi, Plinio (1 January 2001). A History of Medicine: Byzantine and Islamic medicine. Horatius Press. p. 223. ISBN 9781888456042. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- Ira M. Lapidus, Islamic Societies to the Nineteenth Century: A Global History, (Cambridge University Press, 2012), 200.

- "Coptic assembly of America - Reactions in the Egyptian Press To a Lecture Delivered by a Coptic Bishop in Hudson Institute". Archived from the original on 14 July 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Cambridge history of Christanity, pp.197

- Khoury, George (22 January 1997). "The Origins of Middle Eastern Arab Christianity". melkite.com. Archived from the original on 22 February 2001.

- Parry, Ken (1999). Melling, David (ed.). The Blackwell Dictionary of Eastern Christianity. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-631-23203-2.

- Rimon, Ofra. "The Nabateans in the Negev". Hecht Museum. Archived from the original on 20 November 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2011.

- "Petra « See The Holy Land". Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- Philip K. Hitti, History of the Arabs, 6th ed. (Macmillan and St. Martin's Press, 1967, pp. 78-84 (on the Ghassanids and Lakhmids) and pp. 87-108 (on Yemen and the Hijaz).

- , Sabet, Amr (2006), The American Journal of Islamic Social Sciences 24:4, Oxford; page 99–100

- Khadduri, Majid (2010). War and Peace in the Law of Islam, Johns Hopkins University Press; pages 162–224; ISBN 978-1-58477-695-6

- Ali, Abdullah Yusuf (1991). The Holy Quran. Medina: King Fahd Holy Qur-an Printing Complex.

- John Louis Esposito, Islam the Straight Path, Oxford University Press, 15 January 1998, p. 34.

- Lewis (1984), pp. 10, 20

- Timothy George (2002). Is the Father of Jesus the God of Muhammad?: understanding the differences between Christianity and Islam. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-24748-7.

- Gran, Peter (January 2002). "Tahtawi in Paris". Al-Ahram Weekly Online (568). Archived from the original on 24 June 2003.

- Teague, Michael (2010). "The New Christian Question". Al Jadid Magazine. 16 (62). Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Boueiz Kanaan, Claude. Lebanon 1860-1960: A Century of Myth and Politics. la University of Michigan. p. 127.

- Radai, Itamar (2008). "The collapse of the Palestinian-Arab middle class in 1948: The case of Qatamon" (PDF). Middle Eastern Studies. 43 (6): 961–982. doi:10.1080/00263200701568352. ISSN 0026-3206. S2CID 143649224. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- Merrill, A. Fisher, John Calhoun, Harold. The world's great dailies: profiles of fifty newspapers. la University of Michigan. p. 52.

- Lattouf, 2004, p. 70

- محطات مارونية من تاريخ لبنان، مرجع سابق، ص.185

- Benson, Kathleen; Kayal, Philip M.; Museum of the City of New York (2002). A community of many worlds : Arab Americans in New York City. Internet Archive. New York : Museum of the City of New York ; Syracuse : Syracuse University Press. ISBN 978-0-8156-0739-7.

- Starkey, Paul (2006). Modern Arabic literature. Edinburgh University Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-7486-1290-1.

- Belt, Don; editor, ContributorSenior; Geographic", "National (15 June 2009). "Pope to Arab Christians: Keep the Faith". HuffPost. Retrieved 21 January 2021.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Miller, Duane Alexander; Johnstone, Patrick (2015). "Believers in Christ from a Muslim Background: A Global Census" (PDF). Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion. 11: 10.

- "A Church at War: Clergy & Politics in Wartime Lebanon (1975–82)". Providence. 25 September 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- "Migratory flows (16th–19th century) - Syro-Lebanese migration towards Egypt (18th to early 20th century) - Marwan Abi Fadel". hemed.univ-lemans.fr. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- "Le centenaire de la Grande famine au Liban : pour ne jamais oublier". L'Orient-Le Jour. 18 April 2015. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- Lutsky, Vladimir Borisovich (1969). "Modern History of the Arab Countries". Progress Publishers. Retrieved 12 November 2009.

- "Modern History of the Arab Countries by Vladimir Borisovich Lutsky 1969". www.marxists.org. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- France overseas: a study of modern imperialism By Herbert Ingram Priestley p.87

- Ghazal, Rym (14 April 2015). "Lebanon's dark days of hunger: The Great Famine of 1915–18". The National. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- BBC staff (26 November 2014). "Six unexpected WW1 battlegrounds". BBC News. BBC. BBC News Services. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- Ghazal, Rym (14 April 2015). "Lebanon's dark days of hunger: The Great Famine of 1915–18". The National. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- Euronews ن: How an Arabic letter was reclaimed to support Iraq's persecuted Christians

- Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Lebanon". Refworld. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | Syria: The situation of Christians, including whether Christians are perceived to be loyal to President Assad; treatment of Christians by the regime and the opposition forces, including incidents of violence against them; state protection (2013-July 2015)". Refworld. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- Telegraph, Ruth Sherlock, The. "How The Free Syrian Army Became A Largely Criminal Enterprise". Business Insider. Retrieved 22 January 2021.

- "History of street names and districts". Live Achrafieh. 8 February 2012. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 28 February 2012.

- "The World Factbook". Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- "Statistical Abstract of Israel 2010". Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- "CBS report: Christian population in Israel growing". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- Adelman, Jonathan (28 August 2015). "The Christians of Israel: A Remarkable Group". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- "The Christian communities in Israel". Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. 1 May 2014. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- "The Christian communities in Israel". mfa.gov.il.

- "חדשות - בארץ nrg - ...המגזר הערבי נוצרי הכי מצליח במערכת". Nrg.co.il. 25 December 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- "المسيحيون العرب يتفوقون على يهود إسرائيل في التعليم". Bokra. Retrieved 28 December 2011.

- "Christians in Israel: Strong in education - Israel News, Ynetnews". Ynetnews.com. 20 June 1995. Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- "An inside look at Israel's Christian minority". Arutz Sheva. Retrieved 24 December 2017.

- "Christian Arabs top country's matriculation charts". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- http://www.nrg.co.il/online/1/ART2/663/447.html 2% מהישראלים יחגגו מחר עם סנטה קלאוס

- "הלמ"ס: עלייה בשיעור הערבים הנרשמים למוסדות האקדמיים".

- "Israeli Christians Flourishing in Education but Falling in Number". Terrasanta.net. Archived from the original on 7 January 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- "Christians in Israel Well-Off, Statistics Show: Christians in Israel are prosperous and well-educated - but some fear that Muslim intimidation will cause a mass escape to the West". Arutz Sheva. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- "פרק 4 פערים חברתיים-כלכליים בין ערבים לבין יהודים" (PDF). Abrahamfund.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 October 2015. Retrieved 18 September 2016.

- "In Heartwarming Christmas Story, IDF Welcomes More Pro-Israel Christian Arabs". 23 December 2015.

- TLV1 (21 January 2016). "Israeli-Arab Christians take to the streets of Haifa for an unusual protest". TLV1 Radio. Archived from the original on 9 October 2014. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- "First purpose-built church". Guinness World Records. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- Vela, Justin (14 February 2015). "Jordan: The safe haven for Christians fleeing ISIL". The National. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- Fleishman, Jeffrey (10 May 2009). "For Christian enclave in Jordan, tribal lands are sacred". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- Miller, Duane Alexander (30 July 2010). "The Episcopal Church in Jordan: Identity, Liturgy, and Mission". Journal of Anglican Studies. 9 (2): 134–153. doi:10.1017/s1740355309990271.

- "Home - Minority Rights Group". minorityrights.org. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- Freij, Muath (12 August 2015). "Iraqi Christians return to school in Jordan after a year in limbo". jordantimes.com. Archived from the original on 14 August 2015.

- http://www.jordantimes.com/news/region/hundreds-syrian-christians-flee-daesh-%E2%80%94-activists%5B%5D

- "Request Rejected". kingabdullah.jo. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- Kraidy, Marwan (2005). Hybridity, OR the Cultural Logic of Globalization. Temple University. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-59213-144-0.

- "The Lebanese census of 1932 revisited. Who are the Lebanese?". yes. Source: British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, Nov99, Vol. 26 Issue 2, p219, 23p. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- Nasr, Joseph (10 May 2009). "FACTBOX - Christians in Israel, West Bank and Gaza". Reuters.

- Derfner, Larry (7 May 2009). "Persecuted Christians?". The Jerusalem Post.

- Guide: Christians in the Middle East. BBC News. 2011-10-11.

- "Israeli-Palestinian conflict blamed for Christian exodus". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Miller, Duane Alexander; Sumpter, Philip (2016). "Between the Hammer and the Anvil: Indigenous Palestinian Christianity in the West Bank". Christianity and Freedom. pp. 372–396. doi:10.1017/CBO9781316408643.014. ISBN 978-1-316-40864-3.

- "Palestinian Christian Activist Stabbed to Death in Gaza". Haaretz. 7 October 2007. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Oren, Michael. "Israel and the plight of Mideast Christians". Wall Street Journal.

- "Middle East :: Syria — The World Factbook - Central Intelligence Agency". www.cia.gov.

- "Syria". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Martin, Tamcke. "Christen in der islamischen Welt | APuZ". bpb.de.

- Khojoyan, Sara (16 October 2009). "Armenian in Istanbul: Diaspora in Turkey welcomes the setting of relations and waits more steps from both countries". ArmeniaNow.com. Retrieved 5 January 2013.

- The World In one of Turkey's most religiously diverse provinces, close ties with Syria fuel support for Assad regime Retrieved 6 April 2012

- Langfeldt, John A. (1994). "Recently discovered early Christian monuments in Northeastern Arabia". Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. 5: 32–60. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0471.1994.tb00054.x.

- "Nationality By Religion and Nationality" (in Arabic). Government of Kuwait. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 6 December 2015.

- Sharaf, Nihal (2012). "'Christians Enjoy Religious Freedom': Church-State ties excellent". Arabia Times. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015.

- "2010 Census Results". Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- Fahlbusch, Erwin; Bromiley, Geoffrey William; Lochman, Jan Milic; Mbiti, John; Pelikan, Jaroslav; Vischer, Lukas; Barrett, David B. (2003). The Encyclopedia of Christianity: J-O. ISBN 9780802824158. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- "Rising numbers of Christians in Islamic countries could pose threat to social order". World Review. 2013. Archived from the original on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Refworld - Morocco: General situation of Muslims who converted to Christianity, and specifically those who converted to Catholicism; their treatment by Islamists and the authorities, including state protection (2008-2011)". Refworld. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- International Religious Freedom Report 2007: Tunisia. United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (14 September 2007). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- News, Morning Star. "Christian Converts in Morocco Fear Fatwa Calling for Their Execution". News & Reporting.

- "'House-Churches' and Silent Masses —The Converted Christians of Morocco Are Praying in Secret". www.vice.com.

- "Morocco: No more hiding for Christians". Evangelical Focus.

- "Christian Persecution in Tunisia | Open Doors USA". Open Doors USA. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- "New book announcement: Assyrians, Kurds, and Ottomans Intercommunal Relations on the Periphery of the Ottoman Empire" (PDF). Cambria Press. Retrieved 15 August 2016.

- "Assyrians are an ethnically, linguistically and religiously distinct minority in the Middle Eastern region." (PDF)

- Lewis, J. L. (Summer 2003). "Iraqi Assyrians: Barometer of Pluralism". Middle East Quarterly: 49–57. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- "Coalition of American Assyrians and Maronites Rebukes Arab American Institute". Assyrian International News Agency. 27 October 2001. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- Ibrahim, Youssef M. (18 April 1998). "U.S. Bill Has Egypt's Copts Squirming". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 October 2008.

- Cole, Ethan (8 July 2008). "Egypt's Christian-Muslim Gap Growing Bigger". The Christian Post. Archived from the original on 1 February 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2008.

- "Egypt from "U.S. Department of State/Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs"". United States Department of State. 30 September 2008.

- Asher Kauffman (2004). Reviving Phoenicia: The Search for Identity in Lebanon. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 9781860649820. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- The Middle East: From Transition to Development. Brill Archive. 1985. ISBN 978-9004076945. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Kemal Salibi, A House of Many Mansions.

- "The Identity of Lebanon". Mountlebanon.org. Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- "Our Lady of Lebanon Maronite Catholic Church: Easton, Pennsylvania & Kfarsghab, Lebanon". Mountlebanon.org. Retrieved 6 December 2012.

- "Israeli Christians Officially Recognized as Arameans, Not Arabs". Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Berman, Lazar (18 September 2014). "Israeli Christians may define themselves as Aramean". The Times of Israel.

The Interior Ministry contended that in order to be recognized as Aramean, one should be conversant in the Aramaic language, and come from the Maronite, Greek Orthodox, Greek Catholic, Syriac Catholic or Orthodox Aramaic factions, the i24 news outlet reported.

Bibliography

- Sir Ronald Storrs, The Memoirs of Sir Ronald Storrs. Putnam, New York, 1937.

- Itamar Katz and Ruth Kark, 'The Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem and its congregation: dissent over real estate' in The International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 37, 2005.

- Orthodox Shun Patriarch Irineos

- Seth J. Frantzman, The Strength and the Weakness: The Arab Christians in Mandatory Palestine and the 1948 War, unpublished M.A thesis at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- Waardenburg, Jean Jacques (2003). "The Earliest Relations of Islam with Other Religions: The Christians in Northern Arabia". Muslims and Others: Relations in Context. Religion and Reason. 41. Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 94–109. doi:10.1515/9783110200959. ISBN 978-3-11-017627-8. Retrieved 8 December 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Arab Christians. |

.jpg.webp)