Theosis (Eastern Christian theology)

Theosis, or deification (deification may also refer to apotheosis, lit. "making divine"), is a transformative process whose aim is likeness to or union with God, as taught by the Eastern Orthodox Church and Eastern Catholic Churches. As a process of transformation, theosis is brought about by the effects of catharsis (purification of mind and body) and theoria ('illumination' with the 'vision' of God). According to Eastern Christian teachings, theosis is very much the purpose of human life. It is considered achievable only through synergy (or cooperation) of human activity and God's uncreated energies (or operations).[1]

| Part of a series on |

| Palamism |

|---|

.jpg.webp) |

|

|

| Part of a series on the |

| Eastern Orthodox Church |

|---|

| Overview |

| Part of a series on |

| Christian mysticism |

|---|

|

According to Metropolitan Hierotheos (Vlachos), the primacy of theosis in Eastern Orthodox Christian theology is directly related to the fact that Eastern Christian theology (as historically conceived by its principal exponents) is based to a greater extent than Latin Catholic theology on the direct spiritual insights of the saints or mystics of the church rather than the apparently more rational thought tradition of the West.[2] Eastern Christians consider that "no one who does not follow the path of union with God can be a theologian"[3] in the proper sense. Thus theology in Eastern Christianity is not treated primarily as an academic pursuit. Instead it is based on applied revelation (see gnosiology), and the primary validation of a theologian is understood to be a holy and ascetical life rather than intellectual training or academic credentials (see scholasticism).[2]

Deification

Athanasius of Alexandria wrote, "He was incarnate that we might be made god" (Αὐτὸς γὰρ ἐνηνθρώπησεν, ἵνα ἡμεῖς θεοποιηθῶμεν).[4] What would otherwise seem absurd—that fallen, sinful man may become holy as God is holy—has been made possible through Jesus Christ, who is God incarnate. Naturally, the crucial Christian assertion, that God is One, sets an absolute limit on the meaning of theosis: even as it is not possible for any created being to become God ontologically, or even a necessary part of God (of the three existences of God called hypostases), so a created being cannot become Jesus Christ, the Holy Spirit nor the Father of the Trinity.[5]

Most specifically creatures, i.e. created beings, cannot become God in His transcendent essence, or ousia, hyper-being (see apophaticism). Such a concept would be the henosis, or absorption and fusion into God of Greek pagan philosophy. However, every being and reality itself is considered as composed of the immanent energy, or energeia, of God. As energy is the actuality of God, i.e. his immanence, from God's being, it is also the energeia or activity of God. Thus the doctrine avoids pantheism while partially accepting Neoplatonism's terms and general concepts, but not its substance (see Plotinus).[5]

Maximus the Confessor wrote:

A sure warrant for looking forward with hope to deification of human nature is provided by the Incarnation of God, which makes man God to the same degree as God Himself became man. ...Let us become the image of the one whole God, bearing nothing earthly in ourselves, so that we may consort with God and become gods, receiving from God our existence as gods. For it is clear that He Who became man without sin (cf. Heb. 4:15) will divinize human nature without changing it into the Divine Nature, and will raise it up for His Own sake to the same degree as He lowered Himself for man's sake. This is what St[.] Paul teaches mystically when he says, "that in the ages to come he might display the overflowing richness of His grace" (Eph. 2:7)[6]

Theoria

Through theoria (illumination with or direct experience of the Triune God), human beings come to know and experience what it means to be fully human, i.e., the created image of God; through their communion with Jesus Christ, God shares himself with the human race, in order to conform them to all that He is in knowledge, righteousness, and holiness. As God became human, in all ways except sin, he will also make humans "God", i.e., "holy" or "saintly", in all ways except his Divine Essence, which is uncaused and uncreated. Irenaeus explained this doctrine in the work Against Heresies, Book 5, Preface: "the Word of God, our Lord Jesus Christ, Who did, through His transcendent love, become what we are, that He might bring us to be even what He is Himself."

As a patristic and historical teaching

For many Church Fathers, theosis goes beyond simply restoring people to their state before the fall of Adam and Eve, teaching that because Christ united the human and divine natures in Jesus' person, it is now possible for someone to experience closer fellowship with God than Adam and Eve initially experienced in the Garden of Eden, and that people can become more like God than Adam and Eve were at that time. Some Eastern Christian theologians say that Jesus would have become incarnate for this reason alone, even if Adam and Eve had never sinned.[7]

All of humanity is fully restored to the full potential of humanity because the Son of God took to himself a human nature to be born of a woman, and takes to himself also the sufferings due to sin (yet is not himself sinful, and is God unchanged in being). In Christ the two natures of God and human are not two persons but one; thus a union is effected in Christ between all of humanity in principle and God. So the holy God and sinful humanity are reconciled in principle in the one sinless man, Jesus Christ. (See Jesus' prayer as recorded in John 17.)[8]

This reconciliation is made actual through the struggle to conform to the image of Christ. Without the struggle, the praxis, there is no real faith; faith leads to action, without which it is dead. One must unite will, thought, and action to God's will, his thoughts, and his actions. A person must fashion his life to be a mirror, a true likeness of God. More than that, since God and humanity are more than a similarity in Christ but rather a true union, Christians' lives are more than mere imitation and are rather a union with the life of God himself: so that the one who is working out salvation is united with God working within the penitent both to will and to do that which pleases God (Philippians 2:13).

A common analogy for theosis, given by the Greek fathers, is that of a metal which is put into the fire. The metal obtains all the properties of the fire (heat, light), while its essence remains that of a metal.[9] Using the head-body analogy from Paul the Apostle, every man in whom Christ lives partakes of the glory of Christ. As John Chrysostom observes, "where the head is, there is the body also. There is no interval to separate between the Head and the body; for were there a separation, then were it no longer a body, then were it no longer a head."[10]

Stages

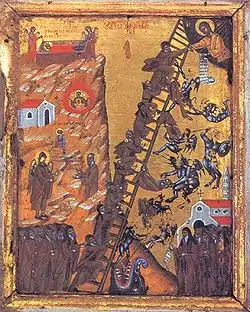

Theosis is understood to have three stages: first, the purgative way, purification, or katharsis; second, illumination, the illuminative way, the vision of God, or theoria; and third, sainthood, the unitive way, or theosis. Thus the term "theosis" describes the whole process and its objective. By means of purification a person comes to theoria and then to theosis. Theosis is the participation of the person in the life of God. According to this doctrine, the holy life of God, given in Jesus Christ to the believer through the Holy Spirit, is expressed through the three stages of theosis, beginning in the struggles of this life, increasing in the experience of knowledge of God, and consummated in the resurrection of the believer, when the victory of God over fear, sin, and death, accomplished in the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus Christ, is made manifest in the believer forever.[11]

Ascetic practice

The journey toward theosis includes many forms of praxis, the most obvious being monasticism and clergy. Of the monastic tradition, the practice of hesychasm is most important as a way to establish a direct relationship with God. Living in the community of the church and partaking regularly of the sacraments, especially the Eucharist, is taken for granted. Also important is cultivating "prayer of the heart", and prayer that never ceases, as Paul exhorts in 1 Thessalonians 5:17. This unceasing prayer of the heart is a dominant theme in the writings of the Fathers, especially in those collected in the Philokalia. It is considered that no one can reach theosis without an impeccable Christian living, crowned by faithful, warm, and, ultimately, silent, continuous Prayer of the Heart.[12]

The "doer" in deification is the Holy Spirit, with whom the human being joins his will to receive this transforming grace by praxis and prayer, and as Gregory Palamas teaches, the Christian mystics are deified as they become filled with the Light of Tabor of the Holy Spirit in the degree that they make themselves open to it by asceticism (divinization being not a one-sided act of God, but a loving cooperation between God and the advanced Christian, which Palamas considers a synergy).[13]

This synergeia or co-operation between God and Man does not lead to mankind being absorbed into the God as was taught in earlier pagan forms of deification like henosis. Rather it expresses unity, in the complementary nature between the created and the creator. Acquisition of the Holy Spirit is key as the acquisition of the Spirit leads to self-realization.[14]

Western attitudes

Western attitudes towards theosis have traditionally been negative. In his article, Bloor highlights various Western theologians who have contributed to what he calls a "stigma" towards theosis.[15] Yet, recent theological discourse has seen a reversal of this, with Bloor drawing upon Western theologians from an array of traditions, whom, he claims, embrace theosis/deification.[15]

The practice of ascetic prayer, called Hesychasm in the Eastern Orthodox Church and Eastern Catholic Churches, "is centered on the enlightenment or deification (... or theosis, in Greek) of man".[16]

Hesychasm is directed to a goal that is not limited to natural life alone and goes beyond this to deification (theosis).[17]

In the past, Roman Catholic theologians generally expressed a negative view of Hesychasm. The doctrine of Gregory Palamas won almost no following in the West,[18] and the distrustful attitude of Barlaam in its regard prevailed among Western theologians, surviving into the early 20th century, as shown in Adrian Fortescue's article on hesychasm in the 1910 Catholic Encyclopedia.[19] Fortescue translated the Greek words ἥσυχος and ἡσυχαστής as "quiet" and "quietist".[20]

In the same period, Edward Pace's article on quietism indicated that, while in the strictest sense quietism is a 17th-century doctrine proposed by Miguel de Molinos, the term is also used more broadly to cover both Indian religions and what Edward Pace called "the vagaries of Hesychasm", thus betraying the same prejudices as Fortescue with regard to hesychasm;[21] and, again in the same period, Siméon Vailhé described some aspects of the teaching of Palamas as "monstrous errors", "heresies" and "a resurrection of polytheism", and called the hesychast method for arriving at perfect contemplation "no more than a crude form of auto-suggestion".[22]

Different concepts of "natural contemplation" existed in the East and in the medieval West.[lower-alpha 1][23]

The twentieth century saw a remarkable change in the attitude of Roman Catholic theologians to Palamas, a "rehabilitation" of him that has led to increasing parts of the Western Church considering him a saint, even if uncanonized.[24] Some Western scholars maintain that there is no conflict between Palamas's teaching and Roman Catholic thought.[25] According to G. Philips, the essence–energies distinction is "a typical example of a perfectly admissible theological pluralism" that is compatible with the Roman Catholic magisterium.[25] Jeffrey D. Finch claims that "the future of East–West rapprochement appears to be overcoming the modern polemics of neo-scholasticism and neo-Palamism".[26] Some Western theologians have incorporated the theology of Palamas into their own thinking.[27]

Pope John Paul II said Catholics should be familiar with "the venerable and ancient tradition of the Eastern Churches", so as to be nourished by it. Among the treasures of that tradition he mentioned in particular:

the teaching of the Cappadocian Fathers on divinization (which) passed into the tradition of all the Eastern Churches and is part of their common heritage. This can be summarized in the thought already expressed by Saint Irenaeus at the end of the second century: God passed into man so that man might pass over to God. This theology of divinization remains one of the achievements particularly dear to Eastern Christian thought.[28]

See also

Notes

- John Meyendorff wrote:

The debate between Barlaam and the hesychasts can probably be best understood in the light of their different interpretations of what St. Maximus the Confessor used to call "natural contemplation" (physikē theōria) or the new state of creative being in Christ. Barlaam – and also medieval Latin tradition – tends to understand this created habitus as a condition for and not a consequence of grace. Palamas, on the contrary, proclaims the overwhelming novelty of the Kingdom of God revealed in Christ, and the gratuitous nature of the divine and saving acts of God. Hence, for him, vision of God cannot depend on human "knowledge".[23]

References

Footnotes

- Bartos 1999, p. 253; Kapsanis 2006.

- Vlachos 1994.

- Lossky 2002, p. 39.

- Athanasius 2011, sec. 54.3, p. 167.

- Lossky 2002, pp. 29–33.

- PHILOKALIA, Volume 2, page 178).

- Lossky 2002, ch. 1.

- Mathewes-Green 2009, p. 12.

- Popov 2012, p. 48.

- Chrysostom 2012.

- Lossky 2002, pp. 8–9, 39, 126, 133, 154, 196.

- Kotsonis, John (2010). "Unceasing Prayer". OrthodoxyToday.org. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- Maloney 2003, p. 173.

- Kapsanis n.d.

- Bloor 2015.

- Chrysostomos 2001, p. 206.

- Fortescue 1910; Horujy 2005.

- Fortescue 1910.

- Andreopoulos 2005, p. 215; Fortescue 1910.

- Fortescue 1910, p. 301.

- Pace 1911.

- Vailhé 1909, p. 768.

- Meyendorff 1983, pp. 12–13.

- Pelikan 1983, p. xi.

- Finch 2007, p. 243.

- Finch 2007, p. 244.

- Ware 2000, p. 186.

- "Pope John Paul II, Orientale Lumen". vatican.va. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

Bibliography

- Andreopoulos, Andreas (2005). Metamorphosis: The Transfiguration in Byzantine Theology and Iconography. Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-88141-295-6.

- Athanasius of Alexandria (2011). On the Incarnation of the Word. Popular Patristics Series. 44. Translated by Behr, John. Yonkers, New York: St Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-88141-427-1.

- Bartos, Emil (1999). Deification in Eastern Orthodox Theology: An Evaluation and Critique of the Theology of Dumitru Stăniloae. Paternoster Biblical and Theological Monographs. Paternoster Press. ISBN 978-0-85364-956-4.

- Bloor, Joshua D. A. (2015). "New Directions in Western Soteriology". Theology. 118 (3): 179–187. doi:10.1177/0040571X14564932. ISSN 2044-2696. S2CID 170547219.

- Chrysostom, John (2012). The Homilies On Various Epistles. Altenmünster, Germany: Jazzybee Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8496-2097-4.

- Chrysostomos (2001). "An Overview of the Hesychastic Controversy" (PDF). Orthodox and Roman Catholic Relations from the Fourth Crusade to the Hesychastic Controversy. Etna, California: Center for Traditionalist Orthodox Studies. pp. 199–232. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- Finch, Jeffrey D. (2007). "Neo-Palamism, Divinizing Grace, and the Breach between East and West". In Christensen, Michael J.; Wittung, Jeffery A. (eds.). Partakers of the Divine Nature: The History and Development of Deificiation in the Christian Traditions. Madison, New Jersey: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-4111-8.

- Fortescue, Adrian (1910). . In Herbermann, Charles G.; Pace, Edward A.; Pallen, Condé B.; Shahan, Thomas J.; Wynne, John J. (eds.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 7. New York: Encyclopedia Press (published 1913). pp. 301–303.

- Horujy, Sergey S. (2005). "Christian Anthropology and Easter-Orthodox (Hesychast) Asceticism" (lecture). Orthodox Fellowship of All Saints of China. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- Kapsanis, George (n.d.) [1992]. Deification as the Purpose of Man's Life. Retrieved 11 June 2017 – via www.greekorthodoxchurch.org.

- ——— (2006). Theosis: The True Purpose of Human Life (PDF) (4th ed.). Mount Athos, Greece: Holy Monastery of St. Gregorios. ISBN 960-7553-26-8. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- Lossky, Vladimir (2002) [1957]. The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church. Crestwood, New York: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-913836-31-6.

- Maloney, George A. (2003). The Undreamed Has Happened: God Lives Within Us. Scranton, Pennsylvania: University of Scranton Press. ISBN 978-1-58966-017-5.

- Mathewes-Green, Frederica (2009). The Jesus Prayer: The Ancient Desert Prayer That Tunes the Heart to God. Brewster, Massachusetts: Paraclete Press. ISBN 978-1-55725-659-1.

- Meyendorff, John (1983). "Introduction". In Meyendorff, John (ed.). Gregory Palamas: The Triads. The Classics of Western Spirituality. Mahwah, New Jersey: Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-2447-3.

- Pace, E. A. (1911). . In Herbermann, Charles G.; Pace, Edward A.; Pallen, Condé B.; Shahan, Thomas J.; Wynne, John J. (eds.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 12. New York: Encyclopedia Press (published 1913). pp. 608–610.

- Pelikan, Jaroslav (1983). "Preface". In Meyendorff, John (ed.). Gregory Palamas: The Triads. The Classics of Western Spirituality. Mahwah, New Jersey: Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-2447-3.

- Popov, Ivan V. (2012). "The Idea of Deification in the Early Eastern Church". In Kharlamov, Vladimir (ed.). Theosis: Deification in Christian Theology. 2. Chapter translated by Jakim, Boris. Cambridge, England: James Clarke and Co. pp. 42–82. ISBN 978-0-227-68033-9. JSTOR j.ctt1cgf30h.7.

- Vailhé, Siméon (1909). . In Herbermann, Charles G.; Pace, Edward A.; Pallen, Condé B.; Shahan, Thomas J.; Wynne, John J. (eds.). Catholic Encyclopedia. 6. New York: Encyclopedia Press (published 1913). pp. 752–772.

- Vlachos, Hierotheos (1994). "The Difference Between Orthodox Spirituality and Other Traditions". Orthodox Spirituality: A Brief Introduction. Levadia, Greece: Birth of the Theotokos Monastery. ISBN 978-960-7070-20-3. Retrieved 10 June 2017 – via Orthodox Christian Information Center.

- Ware, Kallistos (2000). "Eastern Orthodox Theology". In Hastings, Adrian; Mason, Alistair; Pyper, Hugh (eds.). The Oxford Companion to Christian Thought. Oxford University Press. pp. 184–187. ISBN 978-0-19-860024-4.

Further reading

- Anstall, Kharalambos (2007). "Juridical Justification Theology and a Statement of the Orthodox Teaching". In Jersak, Brad; Hardin, Michael (eds.). Stricken by God? Nonviolent Identification and the Victory of Christ. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8028-6287-7.

- Braaten, Carl E.; Jenson, Robert W., eds. (1998). Union with Christ: The New Finnish Interpretation of Luther. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8028-4442-2.

- Christou, Panayiotis (1984). Partakers of God. Brookline, Massachusetts: Holy Cross Orthodox Press. ISBN 978-0-916586-67-6. Retrieved 11 June 2017 – via Myriobiblos.

- Clendenin, Daniel B. (1994). "Partakers of Divinity: The Orthodox Doctrine of Theosis" (PDF). Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society. 37 (3): 365–379. ISSN 0360-8808. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- Gleason, Joseph (2012). "What Is Theosis?". The Orthodox Life. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- Gross, Jules (2003). The Divinization of the Christian According to the Greek Fathers. Translated by Onica, Paul A. Anaheim, California: A & C Press. ISBN 978-0-7363-1600-2.

- Kärkkäinen, Veli-Matti (2005). One with God: Salvation as Deification and Justification. Collegeville, Minnesota: Liturgical Press. ISBN 978-0-8146-2971-0.

- Kangas, Ron (2002). "Becoming God" (PDF). Affirmation & Critique. 7 (2): 3–30. ISSN 1088-6923. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- ——— (2002). "Creation, Satanification, Regeneration, Deification. Part 3: Regeneration for Deification, Regeneration as Deification" (PDF). Affirmation & Critique. 7 (2): 71–83. ISSN 1088-6923. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- Keating, Daniel A. (2007). Deification and Grace. Naples, Florida: Sapientia Press. ISBN 978-1-932589-37-5.

- Mantzaridis, Georgios I. (1984). The Deification of Man: St Gregory Palmas and the Orthodox Tradition. Translated by Sherrard, Liadain. Crestwood, New York: St Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-88141-027-3.

- Marks, Ed (2002). "Deification by Participation in God's Divinity" (PDF). Affirmation & Critique. 7 (2): 47–54. ISSN 1088-6923. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- Marquart, Kurt E. (2000). "Luther and Theosis" (PDF). Concordia Theological Quarterly. 64 (3): 182–205. ISSN 0038-8610. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- Marshall, Bruce D. (2002). "Justification as Declaration and Deification". International Journal of Systematic Theology. 4 (1): 3–28. doi:10.1111/1463-1652.00070. ISSN 1468-2400.

- Meconi, David Vincent (2013). The One Christ: St. Augustine's Theology of Deification. Washington: Catholic University of America Press. ISBN 978-0-8132-2127-4.

- Mosser, Carl (2002). "The Greatest Possible Blessing: Calvin and Deification". Scottish Journal of Theology. 55 (1): 36–57. doi:10.1017/S0036930602000133. ISSN 1475-3065. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- Nellas, Panayiotis (1987). Deification in Christ: Orthodox Perspectives on the Nature of the Human Person. Translated by Russell, Norman. Crestwood, New York: St Vladimir's Seminary Press. ISBN 978-0-88141-030-3.

- Olson, Roger E. (2007). "Deification in Contemporary Theology". Theology Today. 64 (2): 186–200. doi:10.1177/004057360706400205. ISSN 2044-2556. S2CID 170904062.

- Pelikan, Jaroslav (1974). The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine. Volume 2: The Spirit of Eastern Christendom, 600–1700. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-65373-0.

- Pester, John (2002). "The Gospel of the Promised Seed: Deification According to the Organic Pattern in Romans 8 and Philippians 2" (PDF). Affirmation & Critique. 7 (2): 55–69. ISSN 1088-6923. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- Robichaux, Kerry S. (1996). "... That We Might Be Made God" (PDF). Affirmation & Critique. 1 (3): 21–31. ISSN 1088-6923. Retrieved 11 June 2017.

- ——— (2002). "Can Human Beings Become God?" (PDF). Affirmation & Critique. 7 (2): 31–46. ISSN 1088-6923. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- Russell, Norman (1988). "'Partakers of the Divine Nature' (2 Peter 1:4) in the Byzantine Tradition". ΚΑΘΗΓΗΤΡΙΑ: Essays Presented to Joan Hussey for Her 80th Birthday. Camberley, England: Porphyrogenitus. ISBN 978-1-871328-00-4. Retrieved 15 June 2018 – via Myriobiblos.

- ——— (2006). The Doctrine of Deification in the Greek Patristic Tradition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199205974.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-920597-4.

- Shuttleworth, Mark (2005). Theosis: Partaking of the Divine Nature. Ben Lomond, California: Conciliar Press. Retrieved 15 June 2018 – via Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America.

- "Theosis". OrthodoxWiki. Retrieved 15 June 2018.