Merseyrail

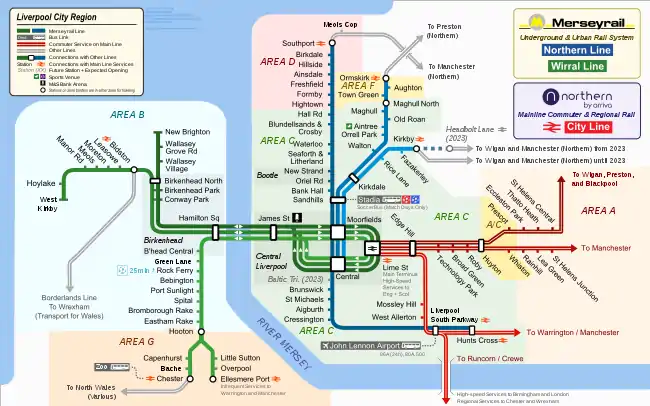

Merseyrail is a suburban railway network serving Liverpool, England, the surrounding Liverpool City Region, the Wirral Peninsula and adjacent areas of Cheshire and Lancashire, including a number of underground stations. The core of the network is formed by two dedicated electrified lines known as the Northern Line and the Wirral Line, which run underground in central Liverpool and Birkenhead. The third line, separate from the electrified network, is named the City Line. The City Line is a term used by the governing body Merseytravel referring to local Northern services it sponsors serving in its area operating on the Liverpool to Manchester Lines and Liverpool to Wigan Line. Many of the City Line stations are branded Merseyrail using Merseyrail ticketing.[1]

.jpg.webp) Northern Line trains at Liverpool Central. | |||

| Overview | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Owner | Merseytravel, Network Rail | ||

| Area served | Liverpool City Region | ||

| Locale | Merseyside Cheshire Lancashire | ||

| Transit type | Commuter rail/Rapid transit | ||

| Number of lines | 2 (plus main line commuter services) | ||

| Number of stations | 68 on the 3rd rail network | ||

| Daily ridership | 110,000 | ||

| Annual ridership | 34,000,000 | ||

| Chief executive | Andy Heath | ||

| Headquarters | Rail House, Liverpool | ||

| Website | www | ||

| Operation | |||

| Began operation | 1977 | ||

| Operator(s) | Serco-Abellio, Network Rail | ||

| Character | Commuter Rail, National Rail Franchise | ||

| Number of vehicles | 57 | ||

| Train length | 3 cars, 6 cars during peak times | ||

| Headway | 15 minutes (general), 5 minutes (central sections), 30 minutes (Ellesmere Port branch, general in evenings and on Sundays) | ||

| Technical | |||

| Track gauge | Standard gauge | ||

| Electrification | 750 volt DC third rail | ||

| |||

The Merseyrail third rail network has 68 stations and 75 miles of route, of which 6.5 miles are underground. Carrying approximately 110,000 passengers each weekday, or 34 million passengers per year, it forms the most heavily used urban railway network in the UK outside London.[2][3][4][5] The network is operated by a joint venture between franchise holder Serco and Abellio, who superseded Arriva Trains Merseyside in 2003. The contract is for 25 years expiring in 2028.[6][7] Serco-Abellio operate a fleet of 59 trains and as of 2015, employ 1,200 people.[8]

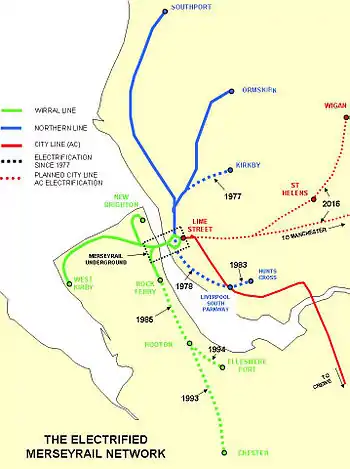

The first part of the large comprehensive urban network was initially opened in 1977 by merging separate rail lines by constructing new tunnels under Liverpool city centre and Birkenhead.[1] Although financial constraints have prevented some of the 1970s plans for the network being realised, the network has been extended on its peripheries, with additional extensions proposed. The extensions were by electrifying existing lines then transferring the sections into Merseyrail.

Point-to-point or return tickets are purchased from staffed offices or ticket machines, but the system is tightly integrated with Merseytravel's City Region-wide pass system, which also encompasses the Mersey Ferries and city and regional bus networks. As of March 2019 Merseytravel ticketing is transitioning to the local Walrus smartcard system, including Merseyrail travel.[9]

The Merseyrail name became the official brand for the network in the days of British Rail, surviving several franchise holders, although the name was not used by Arriva when holding the franchise. Despite this, Merseytravel continued the Merseyrail branding at stations, allowing the name to be adopted colloquially. Merseyrail is referred to as "Merseyrail Electrics" by National Rail Enquiries, and as "Serco/Abellio Merseyrail" by Merseytravel.

Current system

The network is operated by the Merseyrail train operating company. Two lines known as the Northern Line and the Wirral Line with each line having substantial branches compose the network. The lines are electrified throughout using the third-rail 750 V DC system. The Power Supply to the Third Rail is monitored and controlled by the Electric Control Room at Sandhills. The City Line (marked red on the map) is operated primarily by Northern with funding from Merseytravel. The line is mainly electrified with one branch, the Liverpool to Manchester line via Warrington, operated by diesel trains.[10][11]

Trains on the Northern Line and Wirral Line cover the Liverpool City Region. Their total track length is 75 miles (121 km), with 68 stations. The lines connect Liverpool city centre with cities and towns on the outer reaches of the city region, such as Southport, Chester and Ormskirk. Frequent intermediate stops serve other sections of the urban area. Trains run at an off-peak interval of fifteen minutes on most branches, with lines converging to provide a frequency of up to every five minutes within central Liverpool, and under the Mersey to Birkenhead. Although these two lines of the system by the strictest definition only partially fulfil the requirements of a pure rapid transit network (as it uses Network Rail-owned infrastructure), its legislative isolation from the national franchise system, high frequency in the central, underground sections, and operation as a self-contained network make it practically comparable to one or, more accurately, comparable to European S-train systems.

.jpg.webp)

The three lines interchange as follows:

- Northern and City Line services interchange at Liverpool South Parkway and Hunts Cross in the south of the city.

- Wirral and City Lines interchange at Lime Street in the city centre.

- Northern and Wirral lines interchange at Liverpool Central and Moorfields in the city centre

Northern Line

The Northern Line is shown in blue on the Merseyrail map and denoted by the above wordmark on underground stations. Services operate on three main routes: from Hunts Cross in the south of Liverpool to Southport via the Link tunnel from Brunswick Station through central Liverpool, from Liverpool Central to Ormskirk and from Liverpool Central to Kirkby. Each route operates a train every 15 minutes from Monday to Saturday, giving a frequent interval between trains on the central section. Some additional trains run at peak hours on the Southport line.

Connections are available at Southport to Wigan Wallgate and Manchester Airport; at Liverpool South Parkway for services operated by London Northwestern Railway, East Midlands Railway, TransPennine Express and Northern serving Birmingham New Street, Manchester Oxford Road, Blackpool North and various destinations within Yorkshire and the West Midlands; at Hunts Cross to Warrington Central and Manchester Oxford Road; at Ormskirk to Preston and at Kirkby to Wigan Wallgate and Manchester Victoria.[12]

On matchdays at Everton F.C.'s Goodison Park and Liverpool F.C.'s Anfield, Northern Line services connect with the SoccerBus service at Sandhills to transport fans to the stadiums. The buses depart at frequent intervals from Sandhills station with ticketing to combine both methods of travel available. Kirkdale station is within walking distance of Goodison Park.

Wirral Line

The Wirral Line is shown in green on the Merseyrail map being denoted by the above wordmark on underground stations. Services operate from the four Wirral terminus stations of: Chester, Ellesmere Port, New Brighton and West Kirby. Each line from the terminus stations runs through Hamilton Square underground station in Birkenhead then through the Mersey Railway Tunnel, continuing around the single track underground loop tunnel under Liverpool's city centre. Trains head back into the Mersey Railway Tunnel to return to one of the Wirral terminus stations.

Monday-Saturday services are every 15 minutes from Liverpool to Chester, New Brighton and West Kirby, and every 30 minutes to Ellesmere Port (Monday - Sunday). These combine to give a service at least every five minutes from Birkenhead Hamilton Square and around the loop under Liverpool's city centre.[12]

Connections are provided at Bidston on the West Kirby branch for the Borderlands Line to Wrexham, operated by Transport for Wales, and at Chester to Crewe and London Euston, Wrexham and Shrewsbury, the North Wales Coast line to Llandudno and Holyhead, and to Manchester either via Warrington or via Northwich and Knutsford. At Ellesmere Port there is a minimal service to and from Warrington.[12]

City Line

.jpg.webp)

The City Line, shown in red on the Merseyrail map, is a term used by local transport authority Merseytravel to describe the suburban/regional services which depart from the mainline surface platforms at Liverpool Lime Street on the Liverpool–Wigan line, the two routes of the Liverpool–Manchester lines, the Liverpool-Crewe Line, Liverpool-Chester line via Runcorn and the Liverpool-Blackpool line.[13][14][15] The line is denoted by the above wordmark on maps. Merseyrail does not operate the trains or stations; however, the trains stop at two stations operated by Merseyrail. Stopping services running through Merseyside are sponsored by Merseytravel with stations given Merseyrail branding. Services are less frequent than those on the Northern Line and Wirral Line, generally half-hourly on weekdays.

Two services are not electrified, the Manchester via Warrington Central and Chester via Runcorn. Services are provided by the Northern and London Northwestern Railway train operating companies.

In 2015, Class 319 electric multiple units were transferred from the Thameslink route, refurbished, repainted in Northern livery and following the removal of the third rail collector shoes, are operating on the newly electrified lines between Liverpool, Wigan and Manchester, which incorporates the City Line.[11]

Services

Typical weekday off-peak service on the Merseyrail-run Northern and Wirral lines is as follows:[16][17]

| Northern Line | ||

|---|---|---|

| Route | tph | Calling at |

| Hunts Cross to Southport | 4 | Liverpool South Parkway, Cressington, Aigburth, St Michaels, Brunswick, Liverpool Central, Moorfields, Sandhills, Bank Hall, Bootle Oriel Road, Bootle New Strand, Seaforth & Litherland, Waterloo, Blundellsands & Crosby, Hall Road, Hightown, Formby, Freshfield, Ainsdale, Hillside and Birkdale |

| Liverpool Central to Ormskirk | 4 | Moorfields, Sandhills, Kirkdale, Walton, Orrell Park, Aintree, Old Roan, Maghull, Maghull North, Town Green and Aughton Park |

| Liverpool Central to Kirkby | 4 | Moorfields, Sandhills, Kirkdale, Rice Lane and Fazakerley |

| Wirral Line | ||

| Route | tph | Calling at |

| Liverpool Lime Street to New Brighton | 4 | Liverpool Central (from Lime Street only) / Moorfields (to Lime Street only), Liverpool James Street, Birkenhead Hamilton Square, Conway Park, Birkenhead Park, Birkenhead North, Wallasey Village and Wallasey Grove Road |

| Liverpool Lime Street to West Kirby | 4 | Liverpool Central (from Lime Street only) / Moorfields (to Lime Street only), James Street, Hamilton Square, Conway Park, Birkenhead Park, Birkenhead North, Bidston, Leasowe, Moreton, Meols, Manor Road and Hoylake |

| Liverpool Lime Street to Chester | 4 | Liverpool Central (from Lime Street only) / Moorfields (to Lime Street only), James Street, Hamilton Square, Birkenhead Central, Green Lane, Rock Ferry, Bebington, Port Sunlight, Spital, Bromborough Rake, Bromborough, Eastham Rake, Hooton, Capenhurst (2tph) and Bache |

| Liverpool Lime Street to Ellesmere Port | 2 | Liverpool Central (from Lime Street only) / Moorfields (to Lime Street only), James Street, Hamilton Square, Birkenhead Central, Green Lane, Rock Ferry, Bebington, Port Sunlight, Spital, Bromborough Rake, Bromborough, Eastham Rake, Hooton, Little Sutton and Overpool |

City Line services are not operated by Merseyrail, but have timetables produced by Merseytravel and are included here for completeness. Typical off-peak weekday service is as follows:[18]

| City Line | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Route | tph | Calling at | Operator |

| Liverpool Lime Street to Wigan North Western | 2 | Edge Hill, Wavertree Technology Park, Broad Green, Roby, Huyton, Prescot, Eccleston Park, Thatto Heath, St Helens Central, Garswood and Bryn | Northern Trains |

| Liverpool Lime Street to Blackpool North | 1 | Huyton, St Helens Central, Wigan North Western, Euxton Balshaw Lane, Leyland, Preston, Kirkham & Wesham and Poulton-le-Fylde | |

| Liverpool Lime Street to Warrington Bank Quay | 1 | Edge Hill, Wavertree Technology Park, Broad Green, Roby, Huyton, Whiston, Rainhill, Lea Green, St Helens Junction and Earlestown | |

| Liverpool Lime Street to Manchester Airport | 1 | Edge Hill, Wavertree Technology Park, Broad Green, Roby, Huyton, Whiston, Rainhill, Lea Green, St Helens Junction, Earlestown, Newton-le-Willows, Patricroft, Eccles, Manchester Oxford Road, Manchester Piccadilly, Mauldeth Road, Burnage, East Didsbury, Gatley and Heald Green; trains continue to Crewe | |

| Liverpool Lime Street to Manchester Victoria | 1 | Lea Green; trains continue to Scarborough | TransPennine Express |

| 1 | Newton-le-Willows; trains continue to Edinburgh via York and Newcastle | ||

| Liverpool Lime Street to Manchester Oxford Road | 1 | Edge Hill, Mossley Hill, West Allerton, Liverpool South Parkway, Hunts Cross, Halewood, Hough Green, Widnes, Warrington West, Warrington Central, Birchwood, Irlam, Urmston and Deansgate | Northern Trains |

| 0.5 | Mossley Hill, West Allerton, Liverpool South Parkway, Hough Green, Widnes, Warrington Central, Padgate, Birchwood, Glazebrook, Irlam, Flixton, Chassen Road, Urmston and Deansgate | ||

| 0.5 | Mossley Hill, West Allerton, Liverpool South Parkway, Hough Green, Widnes, Warrington Central, Padgate, Birchwood, Irlam, Flixton, Urmston, Humphrey Park, Trafford Park and Deansgate | ||

| Liverpool Lime Street to Manchester Airport | 1 | Liverpool South Parkway, Warrington West, Warrington Central, Birchwood, Manchester Oxford Road, Manchester Piccadilly, Mauldeth Road and East Didsbury | |

| Liverpool Lime Street to Manchester Piccadilly | 1 | Liverpool South Parkway, Widnes, Warrington Central and Manchester Oxford Road; trains continue to Nottingham and Norwich | East Midlands Railway |

| Liverpool Lime Street to Crewe | 2 | Liverpool South Parkway, Runcorn, Acton Bridge (limited), Hartford and Winsford (1tph); trains continue to Birmingham | London Northwestern Railway |

| 1 | Runcorn; trains continue to London | Avanti West Coast | |

Fleet

Services on the electrified Merseyrail network are operated by British Rail Class 507, Class 508 and British Rail Class 777s electric multiple unit trains (EMUs). These replaced pre-war Class 502 (originally constructed by the LMS) and almost identical Class 503 EMUs. There are 57 trains in service on the network. This is down from an initial 76: twelve 508s were transferred to Connex South Eastern in 1996, and a further three were transferred to Silverlink to supplement its fleet of Class 313 EMUs in North London. These train sets had been stored on Merseyside as surplus from during the 1990s.

Two sets have been written off and scrapped. These are unit 507022 in 1991, after a collision, and unit 508118, which had been gutted by fire in an arson attack in Birkenhead in 2001.

The fleet was refurbished between 2002 and 2005 by Alstom at a cost of £32 million, involving trainsets being transported to and from Eastleigh works behind Class 67 locomotives. Improvements to the trains included new high-backed seating, interior panel replacement, new lighting, the installation of a Passenger Information System and a new external livery.[19]

All trains are being phased out in favour of the Class 777 trains.

Current fleet

| Class | Image | Type | Top speed | Carriages | Number | Routes operated | Built | In service | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mph | km/h | ||||||||

| 507 | .jpg.webp) |

EMU | 75 | 120 | 3 | 32 |

|

1978–80 | 1978-2021[20] |

| 508/1 | .jpg.webp) |

EMU | 75 | 120 | 3 | 25 |

|

1979–80 | 1979-2021[20] |

Past fleet

The original service on the Merseyrail lines was provided by British Rail Class 502 on the Northern Line, withdrawn by 1980, and British Rail Class 503 on the Wirral Line from June 1980 onwards,[21] the majority of the Class 503s were progressively withdrawn from June 1984, the final service train running on 29 March 1985.[22]

Merseyrail formerly had four Class 73 electro-diesel locomotives for shunting, sandite trains, engineering works and other departmental duties. These locomotives were sold to a preservation company in 2002.

Future fleet

On 28 January 2020 Swiss rolling-stock manufacturer Stadler Rail provided the first of a new fleet of 52 new train sets, designated Class 777, being built at Stadler's factory in Bussnang, Switzerland. The final units are due to enter service in 2021.[23] Based on the METRO platform, Stadler's product family for underground trains as used on the Berlin U-Bahn and Minsk Metro. The new trains are a custom-built, bespoke design specifically for the Merseyrail network with driver only capability.[24] This differs to the current fleet, which was built to a standard British Rail design for commuter services.

The new trains will be of an articulated four-car design, as opposed to the three-car units currently in service, with a significantly increased overall capacity and faster acceleration and deceleration, which gives reduced journey times. A combination of reduced weight of 99 tonnes, representing a 5.5 tonne weight reduction, and more efficient electrical systems will give a 20% reduction in energy use.

The trains are flexible being capable of operating on a combination of any of: 750 V DC third rail, 25 kV 50 Hz overhead wires or full battery operation using a five-ton battery.[25]

The National Union of Rail, Maritime and Transport Workers opposed driver-only operation on the new fleet, which they said would put passenger safety and security at risk.[26] Following a period of strike action, an agreement was reached to guarantee a guard on every train.[27]

Merseytravel has an option for a further 60 Class 777 units as part of the contract, which if exercised would see a total of 67 trains built if services are extended to new destinations such as: Helsby, Skelmersdale or Wrexham.[23] The deal also involves the transfer of 155 of Merseyrail's maintenance workers and the operation of its maintenance depot at Kirkdale to Stadler Rail Service.[28] The transfer of Kirkdale depot and Merseyrail engineering personnel took place in October 2017, as construction work to modernise the depot, which is the planned maintenance hub for the Class 777s, commenced.[29]

| Trainset | Class | Image | Type | Top speed | Carriages | Number | Planned routes | Built | In service | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mph | km/h | |||||||||

| Stadler Metro | 777 |  |

EMU | 75 | 120 | 4 | 52 |

|

2018–21 | 2020–21 |

Battery trains

The Stadler class 777 trains are capable of being propelled only via onboard battery sets. The battery set per car can be up to five tons in weight. The batteries can be charged via a rail terminal charger and while operating on electrified tracks.[23] Merseyrail will hold trials for battery train operation.

Dual-voltage trains

The new class 777 trains built by Stadler being introduced from 2020 onto Merseyrail, are being built to take power from the 3rd rail electric network. The design gives the capability of dual-voltage operation by adding a catenary for use with overhead wires, giving operation beyond the current network.[30]

Depots

The electric fleet is maintained and stabled at Stadler's maintenance depot and UK headquarters at Kirkdale and Birkenhead North TMD.[31] Minor repair work and stock cleaning is undertaken at Kirkdale, while overhauls are completed at Birkenhead. The roles will be reversed once the Class 777 trains fully replace the existing fleet.[32] Other depots at Hall Road and Birkenhead Central were closed in 1997, and the former was demolished in April 2009.[33] The Birkenhead Central depot is proposed for reopening.[34]

There are also two depots near Southport station: Southport Wall Sidings and Southport Carriage Holding Sidings.

Franchise and concession history

As a result of the privatisation of British Rail, the Northern Line and Wirral Line were brought together as the Mersey Rail Electrics passenger franchise, being sold on 19 January 1997. Although franchises are awarded and administered on a national level (initially through various independent bodies, and later the Department of Transport directly), under the original privatisation legislation of 1993, Passenger Transport Executives (PTEs) were co-signatories of franchise agreements covering their areas - this role being later modified by the 2005 Transport Act.[35]

The first train operating company awarded the Mersey Rail Electrics franchise contract was MTL, originally the operating arm of the PTE, but privatised itself in 1985. They used the brand name Merseyrail Electrics, but after MTL was sold to Arriva, the train operating company was rebranded Arriva Trains Merseyside from 27 April 2001.

The City Line was also privatised under the 1993 Act, but as part of a different, much larger North West Regional Railways (NWRR) franchise. Upon sale on 2 March 1997, the first train operating company awarded the NWRR franchise contract was North Western Trains (owned by Great Western Holdings). The train operating company was later bought by FirstGroup and rebranded First North Western.

When the Mersey Rail Electrics franchise came up for renewal, reflecting the exclusive nature of the Northern and Wirral lines - being largely isolated from the rest of the National Rail network and with no through passenger services to/from outside the Merseyrail network, the decision was taken to remove it from the national franchising system and bring it into exclusive PTE control. As a result, using the Merseyrail Electrics Network Order 2002 the Secretary of State first exempted the two lines from being designated as a railway franchise under the 1993 Act. Coming into force on 20 July 2003, this then allowed the PTE to contract out the operation of the two lines themselves, which they did so as a concession to run for up to 25 years. The first successful bidder was Merseyrail Electrics (2002) Ltd, a joint venture between Serco and NedRailways (renamed Abellio in 2009).[35]

The City Line was not included in the 2003 exemption, and so it has continued as part of the nationally administered rail franchise system. From 11 December 2004, the NWRR franchise was merged into a new Northern franchise. The first train operating company awarded this franchise contract was Northern Rail, also owned by a Serco-NedRail (Abellio) joint venture. Upon re-tendering, Northern Rail failed to retain the contract, and it passed to Arriva Rail North from 1 April 2016.

Due to the isolation of the Northern and Wirral lines, Merseyrail Electrics (2002) Ltd are keen to adopt vertical integration – taking responsibility for maintenance of the track from Network Rail. The current managing director of Merseyrail is Andy Heath.[36]

Performance

Operating as a self-contained network means there are relatively few problems because there is little conflict with other train operating companies. Merseyrail has publicly committed to aiming to be the best train operating company in the UK.[37][38] The latest figures released by NR (Network Rail) (as of period 12 of 2012/2013) report that Merseyrail's Public Performance Measure (PPM) was 96.2% and the moving annual average (MAA) stood at 95.5%.[39]

In February 2010, Merseyrail was named the most reliable operator of trains in the UK, with a reliability average of 96.33% during 2009–2010, the highest ever achieved by any UK train operator.[40]

Financial performance

(Figures shown are attributable to Merseyrail Electrics 2002 Ltd, (who operate the Northern and Wirral Line sections of the "Merseyrail" branded network).

| Year ending | Turnover (£m) | Gross profit (£m) | Trading profit (£m) | Pre-Tax profit (£m) | Retained profit (£m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 2010[41] | 124.5 | 12.1 | 12.5 | ||

| January 2009[42] | 127 | 11.4 | 6.5 | ||

| January 2008[43] | 116 | 9.2 |

Enforcement of by-laws

Merseyrail employs a team of officers who enforce railway by-laws relating to placing feet on seats, travelling without tickets, and other aspects of anti-social behaviour. The enforcement of the 'feet on seat' by-law by Merseyrail was judged to be "draconian"[44] in September 2007; however, Merseyrail stated that it did not want to take offenders to court, but was not allowed to fine offenders otherwise (unlike people who smoke on trains or station platforms).[45] Merseyrail is the only UK train operator to take such a vigorous approach, a stand which Merseyrail claims has proved very popular with commuters and has reduced anti-social behaviour on the system.[46]

History

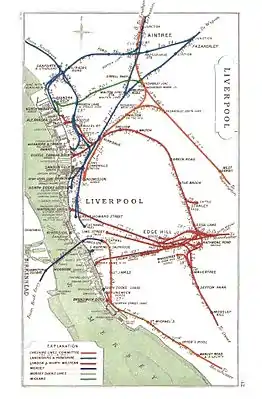

Collection of separate railways

The present Merseyrail system was merged from the lines of five former pre-Grouping rail systems:

- The Mersey Railway (Liverpool Central to Rock Ferry, Birkenhead Park)

- The Cheshire Lines Committee railway (Liverpool Central to Hunts Cross section).

- The Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway (Liverpool Exchange to Kirkby, Ormskirk and Southport sections).

- The Wirral Railway (Birkenhead Park to New Brighton and West Kirby)[47]

- Birkenhead Joint Railway (Rock Ferry to Hooton and Chester section and the Ellesmere Port branch).

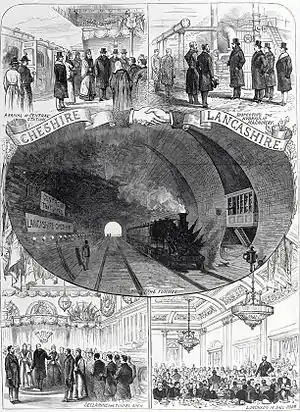

The nucleus of the system was the Mersey Railway, which opened from Liverpool James Street to Green Lane, Birkenhead running through the Mersey Railway Tunnel, one of the world's first underwater railway tunnels in 1886.[12] The tunnelled route was extended to Liverpool Central in 1890. A tunnelled branch to Birkenhead Park was added in 1888 to connect with the Wirral Railway and the original line extended to Rock Ferry to connect with the Birkenhead Woodside to Chester line in 1891.[48]

The Mersey Railway was electrified in 1903 being the world's first full electrification of a steam railway.[12] This was followed by the separate Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway line from Liverpool Exchange to Southport, which was electrified in 1906. The electrification of the former Wirral Railway lines to (New Brighton and West Kirby) took place in 1937 and allowed through running into Liverpool via the Mersey Railway tunnel.

Creation of Merseyrail

The programme of route closures in the early 1960s, known as the Beeching Axe, included the closure of two of Liverpool's mainline terminal stations, Liverpool Exchange and Liverpool Central (High Level), and one on the Wirral, Birkenhead's Woodside Station, leaving only one mainline station serving all of Merseyside at Liverpool Lime Street. Riverside terminal station at the Pier Head was the fourth terminal station to close. This was not a part of the Beeching cuts, however the demise of the trans-Atlantic liner trade forced its closure in 1971. The Beeching Report also recommended that the suburban and outer-suburban commuter rail services into both Exchange and Central High-level stations from the north and south of the city be terminated. Most of these lines were modern electrified lines. Long and medium-distance routes would be concentrated on one mainline terminal station at Lime Street station serving the populations of Liverpool, the Wirral and beyond. The closure of urban lines would create difficulty for large sections of the Merseyside population to access the one remaining mainline station at Liverpool Lime Street.

Liverpool City Council took a different view to Beeching proposing the retention of the suburban services integrating them into a regional electrified rapid-transit network by linking all lines via new tunnels under the centres of Liverpool and Birkenhead. Apart from giving ease of transport around most of Merseyside, the rapid-transit network would give all the regions on the urban lines ease of access to the one remaining mainline station at Liverpool Lime Street, compensating for the loss of three mainline terminal stations. This would have the added benefit of diverting all local urban routes from the mainline terminus station at Lime Street to underground rail in Liverpool's centre. The result would be platforms released from urban use leaving the mainline station to focus on mid to long haul routes. This approach was backed up by the Merseyside Area Land Use and Transportation Study, the MALTS report.[49] Liverpool City Council's proposal was adopted and Merseyrail was born.[50] Unfortunately a small section of the Liverpool to Southport line was not saved from the Beeching Axe. The electrified commuter line from Liverpool Exchange extended to Crossens in the north of Southport. The Southport Chapel Street to Crossens section was on the Southport to Preston line which was axed in 1964.[51]

The Merseyside Passenger Transport Authority, later named Merseytravel, was formed in 1969 with representatives from all Merseyside local authorities taking responsibility for the local rail lines identified to be incorporated into the new network, henceforth known as 'Merseyrail'. At that time, the lines out of Liverpool Exchange, Liverpool Central Low Level, Liverpool Central High Level and Liverpool Lime Street stations were completely separate. The existing electric and diesel hauled lines identified to become the new Merseyrail lines were given the names of 'Northern Line', 'Wirral Line' and 'City Line' respectively. The lines out of Lime Street station would become the City Line, lines out of Exchange and Central High Level the Northern Line and the line out of Central Low Level the Wirral Line. Identifying and naming of the lines was the first stage of Merseyrail's creation.

The Strategic Plan for the North West, the SPNW, in 1973 envisaged that the Outer Loop, the Edge Hill Spur connecting the east of the city to the central underground sections, and the lines to St. Helens, Wigan and Warrington would be electrified and all integrated into Merseyrail by 1991.[52]

To create the comprehensive rapid-transit network four construction projects needed completion:

- The construction of the Loop Line; a tunnel extending the Wirral lines in a loop around Liverpool's city centre, creating the Wirral Line.

- The construction of the Link Line; a tunnel linking the lines north and south radiating out of Liverpool city centre into one. Called the Northern Line, under Liverpool's city centre, it created a north–south crossrail.

- The construction of the Edge Hill Spur; by reusing an 1830 tunnel, the Wapping Tunnel, recently closed in 1972, from Edge Hill junction in the east of the city centre to Central Station in the centre, enabling lines to the east of the city to access the city centre underground section.

- Create the Outer Rail Loop; effectively a rail loop around the outer suburbs of the city using existing lines, that would also run through the city centre. The Northern Line would form the western section through the city centre. The loop would also be split into two loops, one north and one south of Liverpool's city centre, heading for the city centre's Central Station from Broad Green in the east via the Edge Hill Junction. A part of the scheme would be the construction of a six platform underground station at Broad Green where the two loops and the St.Helens/Wigan line met.[53]

Only numbers 1 and 2 listed above were constructed creating the fully electrified 3rd rail Northern and Wirral Lines. Numbers 3 and 4 were cancelled late in the project after some works had actually proceeded. This isolated the City Line preventing integration into the full network with local services still entering mainline Lime St station, occupying platforms that could be used for long haul routes. In the decades following the commissioning of the resulting cut down rapid-transit network, political moves were made to complete the full project, to fully incorporate the City Line into the network, however to no avail.[54] Until the 2015 electrification of the Lime Street to Manchester and Wigan lines, the City Line remained 100% diesel hauled with the Lime Street to Warrington line still retaining diesel traction. In preparation for the full integration of the City Line into the network, the name was maintained with Merseytravel sponsoring the stations that are inside Merseyside, complete with Merseyrail branding.[53]

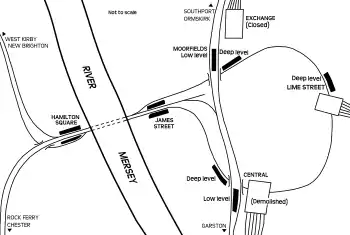

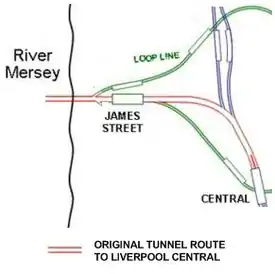

The Loop and Link Project

The major engineering works required to integrate the Northern and Wirral lines became known as the 'Loop' and 'Link' Project, consisting of two tunnels. The 'Loop' was the Wirral Line tunnel and the 'Link' the Northern Line tunnel, both under Liverpool's city centre. The main works were undertaken between 1972 and 1977. A further project, known as the Edge Hill Spur, would have integrated the City Lines into the city centre underground network. This would have meshed the eastern section of the city into the core underground city centre section of the electric network, releasing platforms at mainline Lime Street station for mid to long haul routes. The Edge Hill Spur was not completed due to budget cuts.

The Loop Line (Wirral Line)

The Loop Line is a single-track loop tunnel under Liverpool's city centre serving the Wirral Line branches. It was built to allow both greater capacity and a wider choice of destinations for Wirral Line users, which included the business and shopping districts of Liverpool city centre and mainline Lime Street station. The loop extension offered direct mainline station access to Wirral residents after the decommissioning of the mainline Woodside terminal station in Birkenhead.

Trains from Wirral arriving via the original Mersey Railway tunnel enter the loop beneath Mann Island in Liverpool continuing in a clockwise direction through James Street, Moorfields, Lime Street and Central, returning to the Wirral via James Street station. The loop tunnel gave interchanges for passengers of the Wirral Line to the Northern line at Moorfields and Central stations.[55]

The Link Line (Northern Line)

The purpose of the Link Tunnel was to link the separate urban lines north and south of the city creating a continuous north–south crossrail, called the Northern Line. A substantial section of the Northern Line had an additional function in completing the western section of a planned double-track electrified suburban orbital line, circling the city's outer suburbs, known as the 'Outer Rail Loop'. However, the eastern section of the Outer Rail Loop was never built due to budget cuts.[53]

The Link Line tunnel is a double-track tunnel that links two lines. One line running south from the city centre to Hunts Cross with the second line running north from the city centre to Southport, and the branches off this line to Ormskirk and Kirkby. One continuous line would be created, the Northern Line. The line provides direct access from the north and south of Liverpool to the shopping and business districts in the city centre via two underground stations, Liverpool Central and Moorfields, both of which also interchange with the Loop Line, which is an extension of the Wirral Line. The Northern Line effectively creates a north–south crossrail enabling passengers to travel from the south to the north of the city, and vice versa, via Liverpool city centre.

The present Northern Line underground station at Liverpool Central was originally the Mersey Railway terminus at Liverpool Central Low Level. A section of the original 1880s tunnel between James Street and Central stations was used to form the Link Tunnel. The remainder, between Paradise Street Junction and Derby Square Junction, was retained for use as a rolling stock interchange line between the Northern and Wirral lines and also for a reversing siding for Wirral Line trains terminating at James Street when the Loop Tunnel is inoperative. The rolling stock interchange section of the tunnel is not used for passenger traffic.[56]

The Hamilton Square Burrowing Junction

A burrowing junction was constructed at Birkenhead Hamilton Square station, to increase traffic capacity on the Wirral Line by eliminating the flat junction to the west of the station. This included a new station tunnel at Hamilton Square to serve the lines to New Brighton and West Kirby.

Liverpool Central South Junction

To the south of Liverpool Central Low Level Station, a new track layout was constructed as part of the Link Line project. This layout permitted the former Mersey Railway route to be connected to the former Cheshire Lines Committee route from the closed Central High Level Station and so allow the Northern Line to be extended in a southerly direction to Garston and, later, Hunts Cross. It was accomplished by excavating the trackbed of the high-level tunnel to connect the two routes by means of a gradient. As it was still necessary to accommodate a reversing siding to serve Central Low Level, and as the width of the high-level tunnel did not permit a three-track alignment, a new section of single-track tunnel was built for the Central to Garston line. This tunnel starts to the south of the station and rises to join the high-level tunnel.

At the time of construction, the opportunity was taken to construct two short header tunnels for the proposed Edge Hill Spur project (see below). Should the project go ahead, the connecting tunnels could be constructed without the need to obstruct rail services on the existing route. The junction arrangement would be a burrowing junction, as at Hamilton Square (see above), with the grade separation of tracks increasing capacity. [53]

Expanding the Network (1977 – present)

The Loop and Link project was followed by a programme of expansion, electrification and new stations, which built on the greater integration and capacity provided by the new infrastructure.

Walton to Kirkby

On 30 April 1977, Liverpool Exchange terminus station was closed as a part of the Link tunnel project to create the electrified Merseyrail north-south crossrail line named the Northern Line. Liverpool Exchange was the terminus of the northern Liverpool to Manchester route to Manchester Victoria via Wigan Wallgate station.

A tunnel under Liverpool's city centre, the Link tunnel, created the through crossrail Northern Line. The nearby Moorfields underground through station located on the new Line Link tunnel, serving the Northern and Wirral Lines, replaced Liverpool Exchange terminus station. Since diesel trains could not operate in the underground stations and tunnels for safety reasons, trains that had terminated at Liverpool Exchange terminus from Wigan Wallgate were terminated at Sandhills station as a temporary measure, which is the last surface station before the tunnel.

A year later in 1978, the short line electrification from Walton to Kirkby extended the Merseyrail network, creating a Northern Line branch terminus and interchange station at Kirkby. The line was electrified using the standard 750 V DC third-rail Merseyrail system. The northern Liverpool to Manchester route was cut into two with differing modes of traction, electric and diesel. The diesel Wigan service terminating at Sandhills station was cut back to Kirkby. The Merseyrail electric and the Northern Rail diesel services use opposite ends of the same platform at Kirkby. Merseyrail and Northern Rail trains are generally timed to meet for ease of interchange.

Liverpool Central to Garston

In 1978 the Northern Line extending south from Liverpool Central Station to Garston was made possible by inclining the tunnel into Central High Level from Garston to run down into the lower level tunnel entering Central Low Level from the opposite end of the station forming one continuous tunnel. The linking of the two tunnels had been envisaged when the Mersey Railway was extended to Central from James Street in the 1890s, with the Mersey Railway ensuring the two tunnels were on the same alignment.

The diesel hauled line from Liverpool Central High Level to Gateacre in the south of the city was abandoned in 1972. On reopening under the Merseyrail brand, the electrified line never reached Gateacre as it once did, terminating three stations towards the city centre at Garston. The line was a part of the Northern Line from Garston to terminal stations at Southport, Ormskirk and Kirkby. The complete Northern Line was electrified using the Merseyrail 750 V DC third-rail system.

Garston to Hunts Cross

This short extension of electrified Merseyrail line at the southern end of the Northern Line opened in 1983. It allowed interchange between the Merseyrail Northern Line services with the City Line and main line services from Lime Street. The reopened line passed under the West Coast Main Line Liverpool branch at Allerton but needed to cross the old Cheshire Lines Committee line to Manchester on the flat, which affected capacity.

Rock Ferry to Hooton, Chester and Ellesmere Port

Rock Ferry railway station had been a terminus for Wirral Line services since the Mersey Railway was extended there from Green Lane in 1891. Passengers for the lines to Chester and Helsby would change trains at this station from the electric service on to mainline services, operated by steam and diesel. Rock Ferry became one of the terminals for the Merseyrail Wirral Line. In 1985 the line from Rock Ferry to Hooton was electrified and incorporated in the Wirral Line of Merseyrail, Hooton thus becoming a new terminus.

Hooton is a junction station where the line to Helsby via Ellesmere Port branches off the main Chester line. The line from Hooton to Chester was electrified in 1993, Chester thus becoming a terminus station of the Wirral Line. The line from Hooton to Ellesmere Port was electrified in 1994 and incorporated into the Wirral Line, Ellesmere Port thus also becoming a terminus and interchange station.

New stations

A programme of new stations on the Merseyrail network expanded the coverage of the system. They are as follows:

- Bache: On the Hooton to Chester line, opened in 1983 to replace the former Upton-by-Chester (Halt).

- Bromborough Rake: On the Rock Ferry to Hooton line, opened in 1985 with the completion of electrification to Hooton.

- Overpool: On the Hooton to Ellesmere Port line, opened in 1988.

- (Bache and Overpool are outside the PTE boundary and were funded by Cheshire County Council with some support from Merseytravel).

- Eastham Rake: On the Rock Ferry to Hooton line, opened in 1995.

- Brunswick: On the Liverpool Central to Hunts Cross line, opened in 1998. This station serves the South Docks regeneration area and also the Grafton Street area of Dingle high above the station via a staircase and footbridge.

- Conway Park: On the Hamilton Square to Birkenhead Park underground line, opened in 1998. This station was originally intended to be built as 'cut and cover' with an office building on top. More onerous fire protection requirements arising from the Fennel report into the Kings Cross fire of 1987 made this prohibitively expensive and so the station was constructed in an open cut with lift access to the platforms. It serves the Europa Boulevard area of Birkenhead, a regeneration area.

- Wavertree Technology Park: Opened in 2000 on the City Line route from Edge Hill to Huyton to serve the expanding Technology Park.

- Liverpool South Parkway: Opened in 2006 on the site of Holly Park football ground of South Liverpool F.C. in South Liverpool. It is an interchange station between the Merseyrail Northern Line from Liverpool Central to Hunts Cross and the City Line from Liverpool Lime Street to Runcorn and Warrington Central and also mainline services. The station also includes a bus terminal and large car park and has frequent bus services to Liverpool John Lennon Airport. The station was formed from an amalgamation of the four-track Allerton station and the relocation of the Merseyrail Garston Station. Garston station was closed on the opening of the new facility, the first station closure on the Merseyrail network since Liverpool Exchange station in 1977.[53]

- Maghull North: Construction of this station began in August 2017, with the station opened on 18 June 2018.[57]

Future

There have been various suggestions for ways to enlarge the Merseyrail network.[58] Some would extend beyond the current area, while others would use former existing lines or track beds. In November 2016 the details of the next phase of the Merseyrail fleet were announced: if trains capable of use beyond the third-rail DC network are selected as replacements, various expansions can be achieved without electrification of the entire new route.[59] In August 2014 Merseytravel gave details of a 30-year plan for the network to be presented to the leaders of the city region.[60] the full plan is available at Liverpool City Region Long Term Rail Strategy

St.James Station

Liverpool City Region Combined Authority announced in August 2019 that it was planning to use part of a £172m funding package to reopen St James Station in Liverpool City Centre and a build a new station at Headbolt Lane, Kirkby.[61]

The currently disused St James railway station is located on the corner of St.James' Place and Parliament Street in the Baltic Triangle district being with closure in 1917. The station is in a deep cutting on the operational crossrail Northern Line tunnel section between Liverpool Central Station and Brunswick Station.

In 2020 a series of investments and land purchases advanced the case for a station at the site of St James in the Baltic Triangle.[62][63][64] Part of the Spatial Regeneration Framework for the area includes a new Baltic Triangle railway station[65][66] ]

Headbolt Lane station

A new station at Headbolt Lane north east of Kirkby was first proposed in the 1970s, however a later proposed plan in 2013 failed to receive funding.[67] If built the new station would most probably be on the Liverpool to Skelmersdale line, which will be an extension of the Liverpool to Kirkby line, which has a high probability of construction.[68]

Vauxhall station

In its 30-year plan of 2014 Merseytravel mentions the possibility of a new station between Moorfields and Sandhills in the Vauxhall area.[69]

Tram-trains

In August 2009, it was reported that a new tram-train link to Liverpool John Lennon Airport and a link to Kings Dock from the east of the city had been proposed.[70]

- John Lennon Airport: the existing Northern Line and the City Line from Liverpool Lime Street to Liverpool South Parkway are being assessed. From South Parkway the tram-trains would transfer to a new tramway. Merseytravel commissioned a feasibility study into increasing rail links with the airport in 1995 but no further work has been undertaken.[71]

- Kings Dock to Edge Hill: a link from Edge Hill in the east of the city to the Arena at Kings Dock in the city centre was also being considered.[70]

Battery train trials

The Liverpool City Region Combined Authority, Long Term Rail Strategy document of October 2017, states that trials of new Merseyrail battery trains will be undertaken in 2020. A number of lines have been targeted for electric 3rd rail/battery train trials, which will allow electric Merseyrail trains to operate on unelectrified track, which otherwise would be precluded from track electrification on cost grounds.[72] The lines chosen for the trials are:

- Ellesmere Port to Helsby: On page 37 of the Liverpool City Region Combined Authority, Long Term Rail Strategy document of October 2017, it states that a trial of new Merseyrail battery trains will be undertaken in view to put the 5.2 miles (8.4 km) stretch of track from Ellesmere Port to Helsby interchange station onto the Merseyrail network. If successful, Helsby will be one of the terminals of the Wirral Line replacing Ellesmere Port, with Stanlow and Thornton and Ince and Elton stations brought into the network.[72]

- Ormskirk to Preston: Liverpool City Region Combined Authority, Long Term Rail Strategy document of October 2017, page 37, states a review to introduce new Merseyrail battery trains will be undertaken, in view to incorporate Preston onto the Merseyrail network by extending the Merseyrail Northern Line over 15 miles (24 km) from Ormskirk to Preston interchange station. The aim is to have Preston one of the terminals of the Northern Line, with Burscough Junction, Rufford and Croston stations brought onto the Merseyrail network. The document states, "The potential use of battery powered Merseyrail units may improve the business case".[72]

Extending the network via electrification

Many proposals to electrify lines adding them to the existing Merseyrail network have been proposed. However, in 2017 the Department for Transport announced that electrification of lines in Britain will only be where necessary with some planned projects cancelled. Bi-modal trains with combinations of battery-electric, hydrogen fuel cell and diesel engines are the preferred options.[73] Bi-modal battery/electric trains are to be trialled by Merseyrail on some sections of Merseyrail.

Kirkby to Wigan

In 1977, the Liverpool to Kirkby section of the Liverpool-to-Bolton route was electrified being merged into Merseyrail. Kirkby became the terminus of the Northern Line Kirkby branch. The former through service to Bolton was split in two, with passengers wanting to make through journeys having to change at Kirkby from the Merseyrail electric network to the Northern Rail diesel network onwards to Bolton.

The electrification extending Merseyrail through to Wigan Wallgate was a long-term aspiration of Merseytravel in 2014 being identified by Network Rail as a route where electrification would enable new patterns of passenger service to operate.[60][74][75] The aspiration was accelerated in March 2015 with the Electrification Task force placing electrification of the line from Kirkby to Salford Crescent in a Tier 1 priority category.[76][77]

Ormskirk to Preston

Electrification from Ormskirk to Preston has been considered in conjunction with the Burscough Curves reopening detailed below. It would re-establish the most direct Liverpool-Preston route and is one of Merseytravel's long-term aspirations.[74] However, in 2008 Network Rail said the benefit-to-cost ratio of the scheme was insufficient to justify this scheme in the near future[78] though the scheme continued to be mentioned by Network Rail.[75] Third rail electric/battery train trials are to be undertaken in 2020 by Merseyrail on this section of track to provide a Liverpool to Preston service.[72]

Bidston to Wrexham

.JPG.webp)

The north–south aligned Borderlands Line from Bidston south to Wrexham Central is operated by Transport for Wales using diesel trains on unelectrified track. There have been various proposals to electrify some or all of the line over the years. The most recent study, conducted by Network Rail in 2008, investigated the costs of extending the Merseyrail network third-rail electrification to Wrexham. However, when the cost was estimated at £207 million,[79] Merseytravel announced that cheaper overhead line electrification would be considered instead. This would require dual-voltage trains with third-rail and overhead-wire capability.[80] The Welsh government is pushing for improved rail connections between North Wales and Liverpool which may accelerate the electrification of the line,[81] and the scheme continues to be mentioned by Network Rail[75] and Merseytravel.[60] Merseytravel believe that increasing the frequency of the trains will increase the levels of passengers and make the case for electrification stronger.[82]

In March 2015, the introduction of battery powered trains was proposed for the Borderlands line by Network Rail.[83] The Network Rail document proposes using battery powered rolling stock precluding full electrification of the line, also providing a cheaper method of increasing connectivity into the electrified Birkenhead and Liverpool sections of the Wirral line. From the document:

- "In the longer term, potential deployment of rolling stock with the ability to operate on battery power for part of their journey may provide the ability in an affordable manner to improve the service offering between the Wrexham – Bidston route and Liverpool."[83]

KeolisAmey Wales, the operators of the Wales and Borders franchise Transport for Wales, are to use refurbished Class 230 metro trains using electric motor traction supplied with power by on-board batteries.[84] An on-board diesel generator charges the batteries, with regenerative braking extending the battery's charge. The Vivarail built trains will serve the line between Wrexham and Bidston.[85][86] These new trains have put the full electrification of the line on hold. Welsh Economy Secretary, Ken Skates, stated that the Welsh government were in an advanced stage of talks with Merseytravel about running a direct service from Wrexham to Liverpool.[87]

Hunts Cross to Warrington

The Strategic Plan for the North West, the SPNW, in 1973 envisaged that the Liverpool to Warrington line would be electrified and integrated into Merseyrail by 1991 as a part of the Northern Line.[52] In March 2015 the Electrification Task force placed electrifying the line from Liverpool to Manchester via Warrington Central in the Tier 1 priority category.[76]

Southport to Wigan

Southport to Wigan has been identified by Network Rail as a route where electrification in conjunction with extension of electrification from Ormskirk to Preston and reinstatement of the Burscough Curves would enable new patterns of passenger service to operate.[75] In March 2015 the Electrification Task force placed the electrifying of the line from Southport to Salford Crescent via Wigan in the Tier 1 priority category.[76][77]

Other electrification proposals

The Ellesmere Port to Helsby route is included in Merseytravel's rail strategy as a "long-term aspiration".[60][74] No detailed analysis has been carried out into the feasibility. Third rail electric/battery train trials are to be undertaken in 2020 by Merseyrail on this section of track using the new class 777 trains, which may preclude electrification.[72]

Burscough Curves

The Burscough Curves were short chords linking the Ormskirk to Preston Line with the Manchester to Southport Line. The curves allowed northbound trains from Ormskirk to run directly to Southport to the west, and southbound trains from Preston to run west to Southport. The last regular passenger trains ran over the curves in 1962; the tracks were subsequently lifted. The reinstatement of the Burscough Curves would allow direct Preston-Southport & Ormskirk-Southport services and provide an alternative Liverpool-Southport route via Ormskirk. Network Rail has recommended that a strategy for the Burscough Curves be developed further.[75][78]

In a parliamentary debate on 27 April 2011, the Burscough Curves were a prime point of the debate. The transport minister wished to meet former Southport MP John Pugh regarding the reinstatement of the curves.[88] The latest refresh of Merseytravel's Long Term Strategy puts the opening of the curves in Network Rail's CP7 period.[89]

After the new Merseyrail trains have entered service, they will be tested for battery operation and the prospect of using them on the Burscough Curves will be reviewed.[90] Battery train introduction may improve the business case to reopen the Burscough Curves, allowing Northern Line trains to travel from Ormskirk to Southport, giving two routes from Liverpool to Southport. If realised Burscough Junction, Burscough Bridge, New Lane, Bescar Lane and Meols Cop stations may be incorporated into Merseyrail.[72]

Edge Hill to Bootle

Known as either the Canada Dock Branch line or the Bootle Branch line[91] is an unelectrified line running from Edge Hill Junction in the east of the city in a long curve to the container terminal to the north of the city. The line's last passenger trains were withdrawn in 1977. Being the only line currently into Liverpool docks, freight to Seaforth Container Terminal ensures constant use.[92] The line has been mooted on many occasions for electrifying and reopening to passengers, giving scope to reopen stations along its length: Spellow, Walton & Anfield, Breck Road, Tuebrook, Stanley and Edge Lane.[60]

Network Rail investigated options for the Canada Dock Branch in its March 2009 Route Utilisation Strategy for Merseyside[93] and concluded that the expected benefits did not justify the investment in new infrastructure.

The Department for Transport's Rail electrification document of July 2009 stated that the route to Liverpool Docks would be electrified via overhead wires. The Canada Dock Branch Line is the only line into the docks.[92] From the document:

- 70. Electrification of this route will offer electric haulage options for freight.

- There will be an alternative route to Liverpool docks for electrically-operated freight trains, and better opportunities of electrified access to the proposed freight terminal at Parkside near Newton-le-Willows.

The document states "route to Liverpool docks for electrically-operated freight trains", which is the Bootle Branch line being the only line into Liverpool docks. However, the initial phases of electrification scheduled until 2016 do not list this line.[94] This delay may impede the efficiency of Liverpool docks container terminal which is being extended to accommodate the largest post-Panamax container ships increasing container throughput of the terminal by 25%, entailing increased usage of the line. Local residents are campaigning to have the majority of containers to be transported by rail easing road congestion and pollution, which may increase rail traffic even further.[95] This delay in electrification may delay any proposed passenger use for the line.

The Liverpool City Region Combined Authority, Long Term Rail Strategy document of October 2017, page 37, states:

- A long term proposal which will need to be considered alongside the developing freight strategy for the region and the expansion of the Port of Liverpool. The proposal envisages the introduction of passenger services which will operate from the Bootle Branch into Lime Street. An initial study is required to understand fully the freight requirements for the line and what the realistic potential for operating passenger services over the line is.[72]

It was announced in December 2019 that Liverpool City Council had commissioned a feasibility study to see about reopening the Canada Dock Branch to passenger traffic.[96]

North Mersey Branch

The North Mersey Branch from Bootle to Aintree is currently used only by engineering trains to gain access to Merseyrail tracks; however, Merseytravel has long-term goals to reopen and electrify the line.[60][74] The line was considered in the Merseyside Route Utilisation Strategy document, concluding that reopening could not yet be recommended. However, the Route Utilisation Strategy document went on to state:

- The possibility of running passenger trains along the North Mersey and Bootle branches was examined by the RUS and cannot yet be recommended. However, future development and regeneration could lead to increased demand for such services. Any such passenger services would need to be implemented in a way that ensures current and future freight demand can be accommodated. There is also a possibility in the longer term of using other infrastructure, including the disused Wapping and Waterloo tunnels, to provide new journey opportunities.[93]

Skelmersdale Branch

The reopening of a section of the Skelmersdale Branch from Upholland to Skelmersdale town centre has been proposed.[60] The line was completely closed in 1963. This would give Skelmersdale, the second largest town in North West England without a railway service, direct access to Liverpool city centre. Network Rail has recommended that a further feasibility study be carried out.[93][97] In the 1969 MALTS report, this section is referred to as the Tawd Vale branch. In June 2009, the Association of Train Operating Companies, in its Connecting Communities: Expanding Access to the Rail Network report, called for funding for the reopening of the line from Ormskirk to Skelmersdale as part of a £500m scheme to open 33 stations on 14 lines closed in the Beeching Axe, including seven new parkway stations.[98][99] The report proposes extending the line from Ormskirk railway station by laying 3 miles of new single track along the previous route towards Rainford Junction, at a cost estimated to be in the region of £31m. The route is largely intact, however, a slight deviation north of Westhead where houses have been built on the old trackbed would be required. The proposed station would be on the north-west corner of the town near the Skelmersdale Ring Road, next to where the old station once stood.[99][100]

In December 2012 Merseytravel commissioned Network Rail to study route options and costs of connecting to Skelmersdale with Merseytravel contributing £50,000 and West Lancashire Council contributing £100,000.[101] The range of options considered including a simple park and ride on the existing Northern Line Kirkby branch, an extension of the Northern Line Kirkby branch to a new terminus in Skelmersdale and finally a connection from the Northern Line Ormskirk branch, possibly extended to create a loop via Skelmersdale between Kirkby and Ormskirk. Merseytravel are represented on a board led by Lancashire County Council which has developed a flowchart detailing how the scheme may be delivered.[102]

Lancashire County Council announced in January 2017 that the preferred site for the railway terminal station was the former Glenburn Sports College and Skelmersdale College's West Bank Campus. Whilst the council owns the land that Glenburn Sports College occupies, the currently unused West Bank Campus site is owned by Newcastle College and the council have started the process of acquiring this land. A partnership formed between the council, Merseytravel and West Lancashire Borough Council hope to deliver a service of two trains an hour to Liverpool from Skelmersdale.[103] Network Rail expect the construction of the project to start in 2021 with the station being ready in 2023.[104] An October 2014 plan envisaged the station also providing services to Wigan.[105]

On page 36 of the Liverpool City Region Combined Authority, Long Term Rail Strategy document of October 2017, it states that Merseytravel is currently working with Lancashire County Council and Network Rail to develop a plan to extend the Merseyrail network from Kirkby through to Skelmersdale, with work completed in 2019. They are considering 3rd rail electrification and other alternatives with a new station at Headbolt Lane to serve the Northwood area of Kirkby.[72]

The government in April 2020 gave assurances that the Skelemersdale link would be constructed.[68]

The Outer Rail Loop

The Orbital Outer Rail Loop was a part of the initial Merseyrail plans of the 1970s. The route circled the outer fringes of the city of Liverpool using primarily existing rail lines merged to create the loop. With Liverpool city having a semi-circular footprint with the city centre at the western fringe against the River Mersey, the western section of the loop would run through the city centre. The scheme was started along with the creation of Merseyrail however postponed due to cost cutting.

The concept of using the former Cheshire Lines Committee's North Liverpool Extension Line[106] route through the eastern suburbs of Liverpool as the eastern section of a rapid-transit orbital route circling the outskirts of the city first emerged before the Second World War. The proposal was for a 'belt' line using the now demolished Liverpool Overhead Railway, which ran along the river front, as its western section. In the 1960s during the planning for Merseyrail, this was developed into the Outer Rail Loop scheme - an electric rapid-transit passenger line circling the outer districts of the city by using a combination of newly electrified existing lines and a new link tunnel under the city centre merging lines to the north and south of the city centre completing the loop. A feature was that passengers on the mainline radial routes into Lime Street from the east and south could transfer onto the Outer Loop at two parkway interchange stations completing their journey to Liverpool suburbs avoiding the need to travel into the city centre, which would also relieve pressure on Lime Street station - Liverpool South Parkway was one of these stations opening thirty years after the initial proposal. The Outer Loop would have connected the eastern suburbs of the city: Gateacre, Childwall, Broad Green, Knotty Ash, West Derby, Clubmoor and Walton with the city centre.[53]

As finally developed, the Outer Loop consisted of two sub-loops - serving the northern and southern suburbs with both running through the city centre from the east. These sub-loops allowed more direct journeys to the city centre from the eastern suburbs giving the overall scheme greater viability.

The eastern section of the Outer Rail Loop project was cancelled in the late 1970s because of delays and cost overruns on the Loop (Wirral Line) and Link (Northern Line) projects and local political opposition. Only the western section was built of the loop. The project was abandoned as a working proposal by Merseytravel in the 1980s. Much expense was incurred in constructing a large bridge taking the M62 over the eastern section and header tunnels at Liverpool Central station. The route is still largely intact, complete with bridges, although now the eastern section mainly forms the Liverpool Loop Country Park - a walking and cycling trail through the suburbs.

The key components of the Loop were as follows:

The West Section - The existing Merseyrail Electrics Northern Line from Sandhills in the north (later Aintree on the Ormskirk branch) to Hunts Cross. This section includes the most expensive part of the Outer Rail Loop - the Link Line tunnel under Liverpool city centre - and the reopened and electrified line from Liverpool Central to Hunts Cross.

The East Section - The former Cheshire Lines Committee North Liverpool Extension Line initially from Hunts Cross to Walton however amended to Aintree. This is now the Country Park.

The North Section - Originally the CLC line from Walton to Kirkdale via the Breeze Hill tunnel. In later versions of the scheme the North Mersey Branch from Aintree to Bootle was substituted. The latter is still intact although only used by maintenance trains whilst the former is now partially built over.

The Central Section - The central section was a later addition to the plan and effectively divided the loop into two sub-loops and also gave city centre access for the towns east of Merseyside. This included the unrealised Edge Hill Spur scheme from Liverpool Central Low Level to Edge Hill using the Waterloo Tunnel and a section of the City Line from Edge Hill to Broad Green. A major junction was to have been formed at Broad Green with the eastern section of the Outer Loop with a six platform underground station to be named Rocket under the car park of the Rocket pub near the M62/Queens Drive road junction.

The Outer Rail Loop would have been double track throughout and electrified using the 750 V DC third-rail system used by the Merseyrail Electrics network.

Although no official proposals have been made to revive the scheme in recent years, the route is effectively safeguarded with periodic calls being made by local politicians for the revival of the complete project or just the short stretch of route from Hunts Cross to Gateacre. The Gateacre service was the last to operate out of the former Liverpool Central High Level Station prior to its closure in 1972.

Since the postponement of the project, a number of Route Utilisation Strategy documents have mentioned reopening the North Mersey Branch line, the northern section of the loop, to form a passenger link between Bootle and Aintree with stations to serve Ford and Girobank.[53][107]

The Edge Hill Spur

In the 1960s/early 1970s the Edge Hill Spur scheme was proposed, to link the east of the city with the central underground section. It would have extended the Merseyrail underground network from Liverpool Central Station to Edge Hill Station using existing freight tunnels. Although part of the original Merseyrail plan with construction started, the scheme was dropped. A junction and two headers tunnels to facilitate future construction of the Spur, were built south of Central station during the construction of the Northern Line tunnel, which is a Liverpool north-south crossrail line.[108]

The construction of the Spur would have connected the City Line branches to the east of Liverpool into the electrified Merseyrail network and importantly the underground section in Liverpool's city centre. An increase in integration and connectivity of the network would have been achieved. The Spur would have also formed the central section of the proposed Outer Rail Loop splitting the loop into two smaller loops (see Outer Loop section). An additional and substantial benefit was diverting local urban trains entering the city from the east underground in the city centre. This would release platform space at Lime Street mainline terminus station for the use of only mid and long-haul mainline routes.

The initial and cheaper proposal was to re-use the 1829 Wapping freight tunnel, by means of two new single-track tunnels branched off the Northern Line tunnel at a new junction named Liverpool Central South Junction, south of Central Station. The Wapping Tunnel would have given access to Edge Hill via the historic Cavendish cutting, built for the 1830 Liverpool and Manchester Railway. Access to the City Line would have been obtained via a flyover to the east of Edge Hill Station over the main lines from Lime Street. This flyover has since been demolished.

In the early 1970s, Liverpool City Council planners proposed an alternative scheme, which was subsequently adopted. This revised route would permit a new underground station to be constructed to serve Liverpool University, behind the Student's Union building in Mount Pleasant. It would extend the two connecting tunnels from Central Station in a large radius curve to the north, passing beneath the mainline Lime Street station approach cutting accessing Edge Hill via a section of the Waterloo/Victoria Tunnel. On emerging from this tunnel at the existing Edge Hill Station, the route would be on the north side of the main lines thereby removing the need for a flyover.[53]

Although powers were obtained to build this line under the 1975 Merseyside Metropolitan Railway Act, construction was postponed due to the financial cutbacks and political opposition that also halted the Outer Rail Loop project. The east of Liverpool has suffered in many aspects ever since. An attempt was made to revive the project in the mid-1980s but it was found to be not financially viable.

Following the collapse of the Merseytram scheme in 2006, proposals were considered to revive the project, with the route of the tunnels currently safeguarded.[109] Further references are made to the scheme, as a future option, in MerseyTravel's 30-year plan.[60]

A further proposal to resurrect the Edge Hill spur scheme with a new station at Paddington Village was revealed in 2016 by Liverpool's mayor Joe Anderson, as part of a scheme to extend Liverpool's Knowledge Quarter onto the site of the former Archbishop Blanche School.[110] A feasibility study to reopen the Wapping Tunnel was commissioned and delivered in May 2016. The report found that the Wapping Tunnel was in good condition though suffered from flooding in places and would require some remedial work, but that the concept of reopening the tunnel was viable.[111]

References

- "Merseyrail A brief history" (PDF). Merseytravel. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- "Merseytravel Facts and Figures". Merseytravel. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- "Merseyrail performance" (PDF). Merseyrail. Retrieved 12 October 2015.

- "Merseyrail at Serco". Serco. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Merseyrail". Merseytravel. Archived from the original on 9 June 2019. Retrieved 26 March 2018.

- "Abellio Group Head Office" Group corporate website, Abellio, Utrecht, Netherlands, Undate Archived 15 October 2019 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- "Merseyrail corporate information | Merseyrail Electrics | Serco | Abellio". Merseyrail. 20 July 2003. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- "Walrus Card". www.merseytravel.gov.uk. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- "Northern Rail Electric". Northern Rail. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- "Electrifying Liverpool-Manchester". The Rail Engineer. Ashby-de-la-Zouch. 28 November 2012.

- "Merseyrail Trains History". Merseyrail. Archived from the original on 8 September 2008. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Merseyrail Northern Line". Merseyrail. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- "Merseyrail Wirral Line". Merseyrail. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- "Merseyrail City Line". Merseyrail. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- DVV Media Group GmbH. "Merseyrail train refurbishment". Railway Gazette. Retrieved 5 February 2015.

- Houghton, Alistair (16 December 2016). "Merseytravel reveals new £460m train fleet plans - with no train guards". Liverpool Echo. Archived from the original on 14 March 2017. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- "Class 503, a brief history". Andrew Phillips. Archived from the original on 5 February 2016. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- Maund 2009, p. 214

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- O'Dowd, Emily. "Stadler signs £700 million deal to replace the UK's oldest fleet on Liverpool's Merseytravel line". smartrailworld.com. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 4 February 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "'Why I am striking': Train guards write open letter to all passengers". Liverpool Echo. 4 October 2017. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- "All Merseyrail strikes suspended as union hails 'major breakthrough' that could finally end dispute". Liverpool Echo. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- "Merseytravel and Stadler sign new fleet deal, but legal challenge remains". Rail Technology Magazine. 16 February 2017. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- "Construction begins on Kirkdale depot to maintain new Merseyrail fleet". Rail Technology Magazine. 28 September 2017. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- https://www.stadlerrail.com/en/media/article/stadler-signs-contract-build-and-maintain-52-metro-trains-liverpool-city-region/47/

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Route O - Merseyside" (PDF). Network Rail. 30 March 2010. p. 10. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- "Network Rail 2009 Strategic Business Plan - Merseyrail Route 21" (PDF). Network Rail. 2009. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20171107021632/http://moderngov.merseytravel.uk.net/documents/s21686/Enc.%201%20for%20Updated%20Long%20term%20Rail%20Strategy.pdf

- House of Common Briefing Paper SN6521 Railways: franchising policy, 30 September 2015, Louise Butcher

- "Andy Heath appointed new managing director of Merseyrail". Merseyrail. Merseyrail. Archived from the original on 6 January 2021. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- Hodgson, Neil (4 December 2007). "We have taken the 'misery' out of Merseyrail". Liverpool Echo.

- Hodgson, Neil (14 December 2007). "Merseyrail trains in first place". Liverpool Echo.

- "Performance by train operator". Network Rail. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2012.

- Weston, Alan (11 February 2010). "Merseyrail trains are most reliable in the UK". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved 22 March 2010.

- Turner, Alex (27 October 2010). "Merseyrail profits gather speed to reach record levels". Liverpool Daily Post. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- Turnbull, Barry (27 April 2009). "Merseyrail in record profits surge". Liverpool Daily Post. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- "Culture year is a boon for Merseyrail". Liverpool Daily Post. 10 September 2008. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- Neild, Larry (5 September 2007). "Merseyrail takes 840 to court over feet on seats". Liverpool Daily Post.

- Neild, Larry (11 September 2007). "Is Merseyrail's feet on seats policy too harsh?". Liverpool Daily Post.

- "Merseyrail - train times & timetables, journey planner & service updates". merseyrail.org.

- "Liverpool Merseyrail". UrbanRail. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2009.

- "Birkenhead Monks Ferry". Disused Station. Retrieved 21 July 2009.