West Midlands Metro

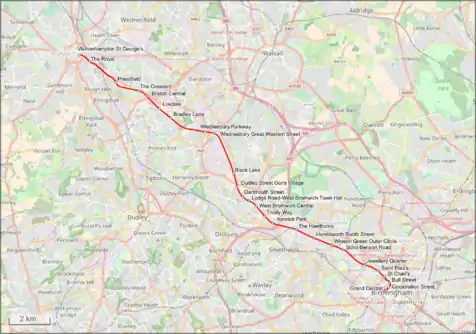

West Midlands Metro (originally named Midland Metro) is a light-rail/tram system in the county of West Midlands, England. Opened on 30 May 1999, it consists of a single route, Line 1, which operates between the cities of Birmingham and Wolverhampton via the towns of West Bromwich and Wednesbury, running on a mixture of reopened disused railway line (the Birmingham Snow Hill to Wolverhampton Low Level Line) and on-street running in urban areas. The line originally terminated at Birmingham Snow Hill station, but with extensions opened in 2015 and 2019, now runs into Birmingham City Centre to terminate at Library in Centenary Square, with a further extension to Edgbaston due to open in 2021.

The system is owned by the public body Transport for West Midlands, and operated through Midland Metro Ltd, a company wholly owned by the West Midlands Combined Authority.[3][4]

Extensions to Line 1, to Edgbaston at the southern end and Wolverhampton railway station in the north are under construction with passenger services expected to commence in 2021.[5] Construction of a new Line 2 from Wednesbury to Brierley Hill was approved in March 2019 and started in February 2020 and due to be completed in 2022 for the Commonwealth Games. A further extension will create a new Line 3 from Edgbaston to Curzon Street, Digbeth, Solihull or Chelmsley Wood and Birmingham Airport planned to open in phases in 2023 and 2024-2026 depending on when planning permission is accepted.[6]

History

Birmingham once had an extensive tram network run by Birmingham Corporation Tramways. However, as in most British cities, the network was wound down and closed by the local authority, with the last tram running in 1953.[7]

1984 proposals

There had been proposals for a light rail or Metro system in Birmingham and the Black Country put forward as early as the 1950s and 1960s, ironically at a time when some of the region's lines and services were beginning to be cut back.[8] However, serious inquiry into the possibility started in 1981 when the West Midlands County Council and the West Midlands Passenger Transport Executive formed a joint planning committee to look at light rail as a means of solving the conurbation's congestion problems. In the summer of 1984 they produced a report entitled "Rapid Transit for the West Midlands" which set out ambitious proposals for a £500 million network of ten light rail routes which would be predominantly street running, but would include some underground sections in Birmingham city centre. One of the proposed routes would have used part of the existing line as far as West Bromwich.[9]

The scheme suffered from several drawbacks, one being that three of the proposed routes, from Birmingham to Sutton Coldfield, Shirley, and Dorridge would take over existing railways, and would have included the conversion into a tramway of the Cross-City Line, between Aston and Blake Street, ending direct rail services to Lichfield. The northern section of the North Warwickshire Line was also to be converted as far as Shirley station, leaving a question mark over existing train services to Stratford-upon-Avon. Tram tracks would also run alongside the existing line to Solihull and Dorridge, with local train services ended.[9]

The most serious drawback however, which proved fatal to the scheme, was that the first proposed route of the network, between Five Ways and Castle Bromwich via the city centre would have involved the demolition of 238 properties. This invoked strong opposition from local residents. The scheme was spearheaded by Wednesfield Labour councillor Phil Bateman,[9] but was eventually abandoned in late 1985 in the face of public opposition, and the Transport Executive was unable to find a Member of Parliament willing to sponsor an enabling Bill.[10]

1988 proposals

Following the abolition of the West Midlands County Council and establishment of a new Passenger Transport Authority in 1986, a new light-rail scheme under the name "Midland Metro" was revived with a different set of lines. The first of up to 15 lines was intended to be operating by the end of 1993, and a network of 200 kilometres was planned to be in use by 2000.[11]

In February 1988, it was announced that the first route, Line 1, would be between Birmingham and Wolverhampton, using much of the mothballed trackbed of the former Birmingham Snow Hill to Wolverhampton Low Level Line, a route not included in the 1984 recommended network, partly as at that stage the section between Wednesbury and Bilston was still in use, not closing until 1992. The Wednesbury to Birmingham section had closed back in 1972, and the section between Bilston and Wolverhampton was last used in 1983.

A Bill to give West Midlands Passenger Transport Executive powers to build the line was deposited in Parliament in November 1988, and became an Act of Parliament a year later, with completion expected by the mid 1990s.[12]

A three-line network was initially planned, and powers were also obtained to build two further routes. Firstly an extension of Line 1 through the city centre to Five Ways, then a second line, Midland Metro Line 2, running to Chelmsley Wood, and then Birmingham Airport.[13] A third line, Line 3 was also proposed, running from Line 1 at Wolverhampton to Walsall, using much of the disused trackbed of the Wolverhampton and Walsall Railway, and then, using the Wednesbury to Brierley Hill trackbed of the South Staffordshire Line (which would close in 1993), running southwards to Dudley intersecting with Line 1 along the route. This would provide a direct link with the new Merry Hill Shopping Centre, which was built between 1984 and 1989.[12]

Some 25 years later, Line 2 and Line 3 have not been built. In 1997 Centro accepted that they were unable to get funding for the proposed lines, and therefore adopted a strategy of expanding the system in "bite-sized chunks", with the city-centre extension of Line 1 as the first priority. The intention was that the first decade of the 21st century would see the completion of the first of these projects.[12][14]

Work on the Birmingham Metro tram extension began in June 2012, launched by transport minister Norman Baker. The dig was begun at the junction of Corporation Street and Bull Street, with work to move water pipes and power cables.

On Sunday 6 December 2015, trams entered service on the extension to Bull Street.

Construction of Line 1

A contract for the construction and operation of Line 1 was awarded to the Altram consortium in August 1995, and construction began three months later.[15]

The estimated construction cost in 1995 was £145 million, of which loans and grants from central government accounted for £80m, the European Regional Development Fund contributed £31m, while the West Midlands Passenger Transport Authority provided £17.1m and Altram contributed £11.4m.[16] The targeted completion date of August 1998 was missed by ten months, leading to compensation being paid by Altram.[17] The original part of Line 1, Birmingham to Wolverhampton, was opened on 30 May 1999.

Current network

Route

There is only one route, Line 1, Birmingham to Wolverhampton, which runs mostly along the trackbed of the former Great Western Railway line between the two cities which was closed in 1972. Originally, the line terminated at Birmingham Snow Hill station, using the space of one of the former rail platforms. However, in 2015-16, the line was extended across Birmingham city centre as far as Birmingham New Street station, and since December 2019, trams now terminate in Centenary Square at Birmingham Library.[18]

From the Grand Central tram stop, which allows interchange with the National Rail network at Birmingham New Street station, West Midlands Metro then runs on street through the city-centre to Birmingham Snow Hill station. From there, the line runs north-west, and for the first few miles it runs alongside the Birmingham to Worcester railway line, before the two diverge. Two stations on this stretch (Jewellery Quarter and The Hawthorns) are also tram/railway interchange stations.[19]

At the northern end trams leave the railway trackbed at Priestfield to run along Bilston Road to St George's terminus in Bilston Street, Wolverhampton city centre. St George's has no direct interchange with other public transport, but the bus and railway stations can be reached on foot in a few minutes.

The original proposal was to run into the former Wolverhampton Low Level station, giving the terminus a link to the very centre of Wolverhampton, but this was abandoned.[20]

Stops

There are 28 tram stops in use on Line 1.

Rolling stock

Current fleet

West Midlands Metro operates 21 trams, with more on order. In summary:[23]

| Class | Image | Type | Top speed | Length metres |

Capacity | In service |

Orders | Fleet numbers |

Routes operated |

Built | Years operated | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mph | km/h | Std | Sdg | Total | ||||||||||

| CAF Urbos 3 |  |

Tram | 43 | 70 | 33 | 54 | 156 | 210 | 21 | — | 17–37 | Line 1 | 2012–2015 | 2014–present |

| — | 21 | TBA | Deliveries from 2021 (Order includes option for a further 29 trams) | |||||||||||

| Total | 21 | 21 | ||||||||||||

CAF Urbos 3

In February 2012, Centro announced that it was planning a £44.2 million replacement of the entire existing T-69 tram fleet.[24] CAF was named preferred bidder for 19 to 25 Urbos 3 trams.[25] A £40 million order for 20 was signed, with options for five more.[26] The new fleet provided an increased service of 10 trams per hour in each direction, with an increased capacity of 210 passengers per tram (compared to 156 passengers on the T69 trams).

The first four new trams entered service on 5 September 2014; all of the T-69s had been replaced by August 2015.[27]

In October 2019, WMCA awarded CAF a contract to supply an additional 21 Urbos 3 trams worth £83.5 million for the expanding network, with the option to purchase a further 29. The contract includes technical support and battery management services over 30 years.

Former fleet

West Midlands Metro has previously operated the following trams:

| Class | Image | Type | Top speed | Length metres |

Capacity | Number | Fleet numbers |

Routes operated |

Built | Years operated | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mph | km/h | Std | Sdg | Total | |||||||||

| AnsaldoBreda T-69 |  |

Tram | 43.5 | 70 | 24.36 | 56 | 100 | 156 | 16 | 01–16 | Line 1 | 1996–1999 | 1999–2015 |

T-69

The T-69s were built in Italy by AnsaldoBreda (now Hitachi Rail Italy), and were used only on the Midland Metro (as it was called then). After withdrawal, all sixteen were transferred to the tram test centre at Long Marston. Most of the trams were sold for scrap, but four of them still remain at Long Marston.[28]

Infrastructure

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Track

Line 1 is a standard gauge double-track tramway. Trams are driven manually under a mix of line-of-sight and signals. Turnback crossovers along the line, including in the street section, have point indicators.

On the trackbed section Birmingham to Priestfield, signals are at Black Lake level crossing, Wednesbury Parkway, and Metro Centre. The street section has signals at every set of traffic lights, tied into the road signals to allow tram priority.

Tram stop design

The tram stops are unstaffed raised platforms with two open-fronted cantilever shelters equipped with seats, a 'live' digital display of services, closed circuit television, and an intercom linked to Metro Centre.[16]

Power supply

The line is electrified at 750 V DC using overhead lines. The system was renewed in 2010/11, requiring short-term closures.[29][30]

Depot

The Metro Centre control room, stabling point and depot is near Wednesbury Great Western Street tram stop, on land once used as railway sidings.

Fares and ticketing

Unlike many other tram and train networks in the UK, West Midlands Metro does not offer ticket machines or ticket offices at tram stops although machines were provided when the system opened. They were later replaced by conductors. Single, return, and all-day tickets are sold by the on-tram conductors. Tickets valid for 1, 4, or 52 weeks are sold from seven "Travel Shops" located around the West Midlands, though only four are in locations served by the Metro.

Up until 2018 single, return, and day tickets could only be purchased with cash or Swift cards. Contactless payment cards are now accepted, though notes larger than £10 are not. Using a Swift card attracts a small discount, usually 10p.

As well as the above, West Midlands Metro accepts a range of interavailable Network West Midlands tickets such as nbus+Metro and nNetwork, which can be bought on buses and at railway stations, as well as on the trams.

Cash fares are distance-related. The scale was originally intended to be broadly comparable with buses, but this caused the system to run at a significant loss and fares rose.[31] In January 2013 the adult single fare from Birmingham to Wolverhampton was £2 by bus and £3.60 by tram, although the tram journey is much quicker even when the bus routes are congestion-free. By 2016 the tram fare had risen to £4.[32] In November 2013 Birmingham City Council indicated plans to introduce a smart-card system (similar to Transport for London's Oyster Card) to improve access, alongside a range of measures including a new Tube-style map and electric bus networks.[33] This has now launched and is called the Swift card.

Corporate affairs

Operator

When the Midland Metro system opened in 1999, it was originally operated by Altram, a joint venture of the infrastructure company John Laing, the engineering firm Ansaldo, and the transport group National Express. In 2006, Ansaldo and Laing officially withdrew from the venture after financial difficulties, and day-to-day operation was taken over by the remaining partner, National Express, who ran the system as National Express Midland Metro.[34]

In October 2018, the National Express concession ended and the system was taken over by Transport for West Midlands, the transport arm of the West Midlands Combined Authority (WMCA). Operation of Midland Metro was taken over by Midland Metro Ltd, a company wholly owned by WMCA, and the system was rebranded West Midlands Metro.[35][3][4] WMCA subsequently set up a consortium of various engineering and consultancy firms, the Midland Metro Alliance, to design and construct future network extensions.[5]

Business trends

The current operator, Midland Metro Ltd, has produced accounts from 1 October 2017.[36] (Beforehand, between 1999 and 2003, Altram had operated Midland Metro unsuccessfully on a for-profit basis. However, operating revenue did not cover costs, and in February 2003, auditors refused to sign off Midland Metro's accounts as a going concern.[34][37] From 2006, under National Express, losses were largely covered by cross-subsidy from other parts of the National Express group,[34] but the figures were not shown separately in their published accounts.)

Passenger revenue and passenger numbers are published by the Department of Transport.[38]

The key available trends in recent years for West Midlands Metro are (years ending 31 March):

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turnover[lower-alpha 1] (£m) | 8.3 (18m) |

|||||||||||

| Operating profit[lower-alpha 2] (£m) | −0.8 (18m) |

|||||||||||

| Passenger revenue[lower-alpha 3] (£m) | 6.6 | 6.5 | 7.0 | 7.4 | 7.8 | 7.9 | 7.7 | 8.6 | 10.3 | 9.8 | 10.7 | 11.3 |

| Number of employees (average) | 181 | |||||||||||

| Number of passengers (m) | 4.7 | 4.7 | 4.8 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 4.7 | 4.4 | 4.8 | 6.2 | 5.7 | 8.3 | 8.0 |

| Number of trams (at year end) | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 |

| Notes/sources | [38] | [38] | [38] | [38] | [38] | [38] | [38] | [38] | [38] | [38] | [38][36] | [38] |

Passenger numbers

Detailed passenger journeys since the system commenced operations on 30 May 1999 were:

| Estimated passenger journeys made on West Midlands Metro per financial year (to 31 March) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Passenger journeys |

Year | Passenger journeys |

Year | Passenger journeys | ||

| 1999/00 | 4.8m | 2007/08 | 4.8m | 2015/16 | 4.8m | ||

| 2000/01 | 5.4m | 2008/09 | 4.7m | 2016/17 | 6.2m | ||

| 2001/02 | 4.8m | 2009/10 | 4.7m | 2017/18 | 5.7m | ||

| 2002/03 | 4.9m | 2010/11 | 4.8m | 2018/19 | 8.3m | ||

| 2003/04 | 5.1m | 2011/12 | 4.9m | 2019/20 | 8.0m | ||

| 2004/05 | 5.0m | 2012/13 | 4.8m | ||||

| 2005/06 | 5.1m | 2013/14 | 4.7m | ||||

| 2006/07 | 4.9m | 2014/15 | 4.4m | ||||

| Estimates from the Department for Transport[39] | |||||||

From the outset, usage on the initial line averaged about five million passengers annually, but numbers remained static for many years.[40] This was not seen as successful,[41][42] as 14 to 20 million passengers per year had been projected.[42][34]

Numerous reasons were suggested for the underperformance, including: that the line has lacked visibility, being confined to Snow Hill station at the edge of Birmingham city centre; that there are quicker trains running between Birmingham and Wolverhampton; that the line did not serve New Street station or any of Birmingham's major visitor attractions (except for the Jewellery Quarter, already well-served by suburban trains).[41][42] Nonetheless, overcrowding sometimes occurred on trams at peak hours.[43]

Following the opening of the extension into Birmingham city centre in June 2016, usage increased sharply.[44] Official figures for 2016/17 showed passenger numbers rose to over six million for the first time.[45]

Branding and livery

The original Midland Metro branding consisted of a blue, green and red livery on tram vehicles with yellow doors. Upon the change to National Express operation in 2006, Midland Metro was rebranded with Network West Midlands livery, then a sub-brand of the transport authority Centro, and trams were painted in a magenta and silver livery with blue doors.[46]

Since 2017, West Midlands Metro has adopted shared branding with other transport modes consisting of a common hexagonal logo formed from the letters WM. This common brand has been introduced in order to created a common identity for an integrated transport system for the region. Each mode bears a coloured variant of the logo: blue for trams, red for buses, orange for trains, magenta for roads, purple for taxis and green for cycling and walking initiatives. The primary typeface is LL Circular by Lineto.[47][48]

Expansion plans

The Midland Metro Alliance was set up in 2017 by WMCA as a long-term framework agreement with transport contractors Colas Rail, Barhale, Thomas Vale, Auctus Management Group, Egis Rail, Tony Gee and Pell Frischman to design and construct future extensions of the West Midlands Metro system.[49]

An extension of Line 1 through Birmingham city centre is under construction and is anticipated to open to passenger services in 2021. An extension through Wolverhampton city centre is also in progress with the same opening date along with a new line from Wednesbury to Brierley Hill through Dudley Town Centre; this is scheduled to open in 2023.[50][51]

Birmingham City Centre extension

West Midlands Metro Line 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Extensions 2016-2021 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Until 2015, the southern end of the Metro line terminated at Snow Hill station, on the periphery of Birmingham City Centre. From its inception, Midland Metro had failed to attain projected passenger numbers and to operate at a profit, and this was attributed to the fact that the line could not carry passengers all the way into the urban centre.[41] The Birmingham City Centre Extension (BCCE) was conceived to solve this problem by extending Line 1 into the streets of central Birmingham. Originally it was planned to terminate the extension at Stephenson Street, adjacent to New Street railway station,[52] but the plans were revised to continue the extension to Birmingham Library. Eventually, Centro hoped to extend the line as far as Five Ways.[53][54][55] A Transport and Works Order authorising the BCCE was made in July 2005,[56] and Government approval was given in February 2012. A new fleet of trams and a new depot at Wednesbury were also authorised, with a budget of £128m, of which £75m was to be funded by the Department for Transport (DfT).[57][58] Extension works began in June 2012.[59]

The extension of Line 1 is taking place in three phases:

- The extension from St Chads to Grand Central was completed in 2016. This extension used a new route to the east of Snow Hill station which diverged from the original line along a new viaduct and descended to street level.[60] The former tram terminus inside Snow Hill station was closed, releasing a fourth platform at Snow Hill to be reinstated for mainline railway use. Interchange between National Rail services and trams is now provided at Bull Street, approximately 320 metres (1,050 ft) from Snow Hill station.[61][62] From Snow Hill a new tramway was built along Colmore Circus, Upper Bull Street, Corporation Street and Stephenson Street, terminating at Grand Central, which opened on 30 May 2016.[63] A temporary reversing spur was built in Stephenson Street to allow trams to turn back for the return journey to Wolverhampton. On 19 November 2015, The Queen visited Birmingham and named one of the new trams.[64]

- The extension from Grand Central to Centenary Square began on 5 September 2017.[65] and was opened to passenger service in December 2019. Trams now run from Stephenson Street along Pinfold Street, through Victoria Square with a new stop at Town Hall, along Paradise Street and Broad Street, and terminate at Birmingham Library in Centenary Square.[66][18][67]

- The Birmingham Westside extension will continue the line from Birmingham Library along Broad Street to Hagley Road in Edgbaston (just west of Five Ways). Additional local enterprise partnership funding was made available in 2014 for the extension from Five Ways to Edgbaston.[68][69][70] The extension is scheduled to be completed in 2021 with new tram stops to be built at Brindleyplace, Five Ways and Edgbaston.[71][72][73]

Wolverhampton City Centre loop

The northern part of the Line 1 extension scheme is the addition of a tram line into Wolverhampton city centre. The laying of the new track was completed in December 2019 and it is anticipated that passenger services will commence in 2021 once the renovation of Wolverhampton railway station has been completed.

It was originally proposed in 2009 as a single-track loop running clockwise from the existing St George's terminus via Princess Street, Lichfield Street and Pipers Row (for Wolverhampton bus station), with a spur to Wolverhampton railway station. The scheme had an estimated cost of £30 million.[74][75] In 2010 Centro considered revised proposals that involved an extended route along part of the Wolverhampton Ring Road, serving the University of Wolverhampton campus.[76] The original loop scheme was selected and in 2012 Centro decided to proceed by constructing it in phases. A Transport and Works Act Order was approved in 2016,[77] and in March 2014, a £2bn connectivity funding package was announced to support a number of transport projects, including phase 1 of the Wolverhampton extension.[78]

The first phase will see the construction of the eastern section of the Wolverhampton loop, consisting of a line branching off before the existing St. George's terminus and running north up Piper's Row to terminate at the railway station. Northbound trams will terminate alternately at the station and at St George's. The estimated completion date was 2015, although as of August 2019 this section is still under construction.[75][79] The remaining part of the Wolverhampton loop will be completed at a later date, subject to funding.[75]

Line 2

It is proposed to extend the West Midlands Metro by constructing two new lines.

Eastside extension

West Midlands Metro Line 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Line One Eastside Extension | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In November 2013, Centro announced a proposal for a tram or bus rapid transit route from Birmingham city centre to Coventry, with a loop connecting the Birmingham Airport with Birmingham city centre via Small Heath and Lea Hall, and a line to Coventry. The line would also serve the planned High Speed 2 interchange at Birmingham Curzon Street.[80][81] In February 2014, it was announced that funding had been secured for the first phase of the Line 2 Eastside extension as far as Curzon Street,[82] before a terminus at Adderley Street.[82]

The new Line 2 would branch off from Line 1 a junction between Bull St and Corporation St. In 2014, Centro considered two proposed routes, one running via Bull Street and Carrs Lane and serving Moor Street station, and a more direct route via Bull Street and Albert Street, bypassing Moor Street.[83]

A Transport and Works Act application has been submitted by the Metro Alliance for the first phase of the Line 2 Eastside extension, following the route via Albert Street and Curzon Street and terminating at Digbeth.[84]

Wednesbury–Brierley Hill extension

West Midlands Metro Line 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Wednesbury-to-Brierley-Hill-extension | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wednesbury–Brierley Hill extension (WBHE) is an 11-kilometre (6.8 mi) line which will run south-west from Line 1, branching off east of Wednesbury Great Western Street. The route would be constructed on the track bed of the disused South Staffordshire Line, running through Tipton and close to the former Dudley Town station. The line would then run on-street into Dudley town centre, before following the A461 Southern Bypass to rejoin the railway corridor. After running along part of the former Oxford, Worcester and Wolverhampton Line, the tram line would diverge south to serve the Waterfront Business Park and Merry Hill Shopping Centre, terminating at Brierley Hill. In 2012 the estimated cost of the WBHE was £268 million, and a frequency of 10 trams per hour was envisaged, alternately serving Wolverhampton and Birmingham.[85][86] A further extension to Stourbridge has also been proposed, with a junction at Canal Street, allowing trams to access the remainder of the South Staffordshire Line to Stourbridge Junction and possibly Stourbridge Town.[87]

Network Rail have announced plans to reopen the South Staffordshire Line for the use of freight trains. Metro planners considered operating light rail trams on segregated tracks, but in 2011 put forward proposals to introduce tram-train operation on the route to allow Metro vehicles to share tracks with heavy rail freight trains.[88][89]

Due to funding constraints, it was decided to construct Line 2 in phases, with the first section from Wednesbury to Dudley opening first.

In early 2017, work began to clear vegetation and disused track from the former railway line. It is estimated that the entire line to Brierley Hill will be completed by 2023.[90] The estimated cost of Line 2 is now £449 million.[91][92]

Historic planned extensions

In 2004, the proposed Phase Two expansion included five routes:[93]

- Birmingham City Centre to Great Barr

- A 10 kilometres (6.2 mi), 17-stop route from the city centre through Lancaster Circus and along the A34 corridor to the Birmingham/Walsall boundary, terminating near the M6 motorway junction 7. Transport for the West Midlands have since decided that a "West Midlands Sprint" concept, based on bus rapid transit is the way forward for this route.

- Birmingham City Centre to Quinton

- A 7.5 kilometres (4.7 mi) route from the BCCE terminus at Five Ways along the Hagley Road to Quinton.

- Wolverhampton City Centre to Wednesfield, Willenhall, Walsall and Wednesbury

- This 20.4 kilometres (12.7 mi) "5Ws" route would connect Wolverhampton city centre to Wednesfield, Willenhall, Walsall and Wednesbury, and provide direct access to New Cross and Manor Hospitals, partially using the trackbed of the former Wolverhampton and Walsall Railway. This link was officially declared dead in the Express & Star on 23 October 2015.[94]

- Birmingham City Centre to Birmingham Airport

- (A45)- A 14 kilometres (8.7 mi) route from Birmingham Airport/ National Exhibition Centre and serving suburbs along the A45 road. Journey time from central Birmingham (Bull Street) to the airport was estimated at 29 minutes. This proposal has now been incorporated into the proposals for Line 2.[95]

- (A47)- In September 2010, the Birmingham Post reported that a "£425 million rapid transit system" between Birmingham city centre and the airport "could involve a new light rail scheme".[96] Centro strategy director Alex Burrows stated "the Birmingham City Centre to Birmingham Airport Rapid Transit plan will deliver connectivity between the city centre, Birmingham Business Park and Chelmsley Wood".[97]

In 2004-05, Birmingham City Council also evaluated the possibility of constructing an underground railway, and the scheme was advocated by the leader of the council, Mike Whitby,[98] and deputy leader of the council, Paul Tilsley.[99] A feasibility report by Jacobs Engineering and Deloitte concluded that the tunnelling scheme would be unaffordable and not meet government funding criteria.[100]

Accidents and incidents

- On 8 June 2006, a tram collided with a taxi on New Swan Lane Level Crossing, which was pushed across the junction and collided with a stationary lorry. The two occupants of the taxi were taken to hospital and released after two hours; neither the tram passengers nor the lorry driver suffered any injuries. The RAIB enquiry found that the tram driver failed to stop at the signal; the report noted that this was then the only level crossing on the network, and that there had been seven previous collisions there since the metro came into operation in 1999, but all of these had been a result of failures on behalf of road traffic users. [101]

See also

- Coventry Very Light Rail - planned light rail system in Coventry

References

- "Light Rail and Tram Statistics, England: 2019/20" (PDF). Department for Transport. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- https://governance.wmca.org.uk/documents/s1639/Appendix.pdf

- "TfWM to take direct control of Midland Metro services". Transport for West Midlands. 22 March 2017.

- "Transport for West Midlands Annual Plan 2018-19" (PDF). West Midlands Combined Authority. 15 April 2018.

- Ltd, DVV Media International. "Midland Metro Alliance to manage tramway expansion projects".

- "£450m funding green light for Midland Metro extension". Construction Enquirer. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- "Birmingham Corporation Transport The Tramways 1872–1953". Archived from the original on 12 February 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- Boynton 2001, pp. 72.

- Boynton 2001, pp. 73.

- Boynton 2001, pp. 74.

- Annual Report 1988–1989. West Midlands PTE.

- "Midland Metro, The Metro Project". Light Rail Transit Association. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- Midland Metro Line 2 map (Map). WMPTE.

- "Midland Metro – City Centre Extension & Fleet Replacement Strategic Case, October 2009". centro.org.uk. Archived from the original on 3 March 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- "House of Commons Debates (pt 27)". UK Parliament. 20 November 1995.

- "Midland Metro Light Rail Network, United Kingdom". Railway Technology. 2011.

- "Big bill for late Midland metro". New Civil Engineer. London. 11 March 1999.

- Young, Graham (11 December 2019). "Midland Metro trams are now running to Centenary Square in Broad Street". Birmingham Mail. Archived from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- "Midland Metro : Tram Stops". thetrams.co.uk. Retrieved 16 March 2013.

- "Wolverhampton Low Level". Subterranea Britannica.

- "Metro". Network West Midlands. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- West Midlands Planning And Transportation Subcommittee (31 July 2009). "Public Transport Update".

- Rackley, Stuart (3 May 2013). "CAF trams for Midland Metro Expansion Project". The Rail Engineer. Coalville. Retrieved 19 November 2013.

- "Midland Metro – City Centre Extension & Fleet Replacement: Delivery, Commercial & Financial Case". Centro. October 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 February 2010.

- "CAF named preferred bidder to supply new Midland Metro trams". Railway Gazette International. London. 2 February 2012.

- "Work begins on £128m Midland Metro expansion project". Railway Gazette International. London. 22 March 2012.

- "New Midland Metro trams launched into service". Centro. 5 September 2014. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- "Midland Metro Fleet List". British Trams Online. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- "Midland Metro to shut for two weeks". Express & Star. Wolverhampton. 11 July 2010.

- "Metro upgrage work taking place later this year". Centro. 2010. Archived from the original on 28 July 2010.

- "Huge losses hit Metro". BBC News. 7 February 2003. Retrieved 12 May 2010.

- Created by One Black Bear (2 January 2016). "Purchasing tickets | Tickets & prices | National Express Midland Metro". Nxbus.co.uk. GB-BIR. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- "Historic Plans to Change Transport in Birmingham". Birmingham Post. 11 November 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- "Anticipated acquisition by West Midlands Travel Limited of the joint venture shares of Laing Infrastructure Holdings Limited and Ansaldo Transporti Sistema Ferroviari SpA in Altram LRT Limited" (PDF). Office of Fair Trading. 2 March 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 October 2008.

- "TfWM to take over running of Midland Metro next year". Rail Technology Magazine. 22 March 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- "Statement of Accounts for the 18 months ended 31 March 2019". Midland Metro Ltd. 30 September 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Court, Mark (12 February 2003). "Auditors at Midland Metro refuse to sign off accounts". The Times. London. Retrieved 12 May 2010. (subscription required)

- "Light rail and tram statistics (LRT)". Department for Transport. 25 June 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- "Passenger journeys on light rail and trams by system: England - annual from 1983/84" (downloadable .ods OpenDocument file). Department For Transport. Retrieved 14 June 2019.

- "Midland Metro – City Centre Extension & Fleet Replacement – Strategic Case". Centro. October 2009. p. 21. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2013.

- "Call for Metro to reach to city centre". Birmingham Post. 24 May 2005. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- Leigh, Stephen. "Midland Metro, A Personal Farewell". British Trams Online. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- Bentley, David (14 February 2013). "Midland Metro line from Birmingham to Wolverhampton to close at Easter for £128m revamp". Birmingham Mail. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- "Midland Metro numbers jump by a third after Birmingham extension". Express & Star. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- "Light Rail and Tram Statistics: England 2016/17" (PDF). Department for Transport. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- "Midland Metro: Trams". TheTrams.co.uk. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- Transport, Transport for West Midlands: Transforming Public. "A brand for the West Midlands – TfWM reveals new public transport identity". Transport for West Midlands. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- "WM Network Brand Guidelines". WMCA Media Assets. West Midlands Combined Authority. Archived from the original on 24 October 2019. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- "About Us". Midland Metro Alliance. WMCA. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- Turton, Andrew. "Tram heads past Birmingham Town Hall on first test of West Midlands Metro line". Express & Star. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- Parkes, Thomas. "Wolverhampton Pipers Row works 'in final stages' but still no date for completion". Express & Star. Retrieved 30 August 2019.

- "Birmingham City Centre Extension and Fleet Replacement". Centro.org.uk. Archived from the original on 1 March 2013. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- "Centro unveils plans to extend the Metro to Centenary Square". The Business Desk. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- Brown, Graeme (15 October 2013). "Major step forward for Midland Metro plans". Birmingham Post.

- "Birmingham City Council Midland Metro". 27 June 2014.

- "The Midland Metro (Birmingham City Centre Extension, etc.) Order 2005". Office of Public Sector Information. 2005. Archived from the original on 23 January 2008.

- Walker, Jonathan (16 February 2012). "£128m Birmingham Midland Metro extension from Snow Hill Station to New Street Station set to create 1,300 jobs gets go-ahead". Birmingham Mail. Archived from the original on 3 August 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- "Construction of Midland Metro extension to begin" (Press release). Department for Transport. 16 February 2012. Archived from the original on 27 April 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2012.

- Lloyd, Matt (14 June 2012). "Transport minister launches scheme to extend Midland Metro to Birmingham New Street". Birmingham Post. Retrieved 14 June 2012.

- "Strategic Case". Centro. Archived from the original on 3 March 2013.

- "Connecting Local Communities" (PDF). Network Rail. 2009.

- Samuel, A. (31 March 2011). "New rail station entrance boosts access to Birmingham". Rail.co. Archived from the original on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2011.

- "Metro - Metro". Centro.org.uk. 17 June 2016. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- "Queen officially reopens New Street station on Birmingham tour". BBC News. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- Iron Man kicks off next phase of Midland Metro expansion Transport for West Midlands 5 September 2017

- "Midland Metro, Birmingham Centenary Square Extension". Centro. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- "Birmingham city centre tram extension opens to passengers ahead of schedule". West Midlands Metro. 11 December 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Birmingham Westside Metro Extension – Midland Metro Alliance". Midland Metro Alliance. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "Midland Metro Extension – Centenary Square to Edgbaston" (PDF). Centreofenterprise.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- "Midland Metro – Extension to Edgbaston (Birmingham) | GBSLEP". Centreofenterprise.com. 30 June 2016. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- Midland Metro extension gets 59.8 million green light from government Department for Transport 1 September 2017

- Midland Metro secures funds for Edgbaston extension International Railway Journal 1 September 2017

- How the new tram to Edgbaston will look Birmingham Mail 2 September 2017

- "Wolverhampton Loop". Centro. February 2009. Archived from the original on 8 February 2010. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "£30m Midland Metro extension plan revived". Express & Star. 2 May 2012. Archived from the original on 31 August 2019. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- Wainwright, Daniel (3 July 2010). "Midland Metro extension to cost £50m". Express & Star. Wolverhampton.

- "Wolves Metro Extension Approved". Modern Railways. Railway Study Association. 73 (815): 21. August 2016.

- Brown, Graeme (12 March 2014). "MIPIM 2014: £2bn Greater Birmingham transport plans take centre stage". Birmingham Post. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- Parkes, Thomas. "Time's up! But Wolverhampton Metro extension works still there". Express & Star. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "Tram line could link Coventry and Birmingham". BBC News. 12 November 2013. Retrieved 13 November 2013.

- Elkes, Neil (8 November 2013). "Birmingham to Coventry Metro Line Being Considered". Birmingham Post. Retrieved 11 November 2013.

- Brown, Graeme (27 February 2014). "£50m invested to take Midland Metro to Curzon Street". Birmingham Post. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- "Birmingham Eastside Extension The details". Archived from the original on 16 March 2014. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- "Birmingham Eastside Metro Extension – Midland Metro Alliance". Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "Wednesbury To Brierley Hill Metro Extension – Midland Metro Alliance". Midland Metro Alliance. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "Wednesbury to Brierley Hill Extension Information". Centro. Archived from the original on 9 April 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- "The Route" (Press release). Centro. Archived from the original on 17 January 2016.

- "Midland Metro track-share proposals gather pace" (Press release). Centro. 22 August 2008. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- "Tram-train line work could launch in 2014". Express & Star. Wolverhampton. 21 March 2011. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- "'Exciting future' for Dudley as tram works begin". BBC News. 29 January 2020. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- "Second line of Midland Metro to be built in phases". Express & Star. Wolverhampton. 24 December 2012. Retrieved 7 March 2013.

- Madeley, Pete. "New West Midland Metro line back on track - but costs are up £100m". Express & Star. Retrieved 31 August 2019.

- "Local Transport Plan, Light Rail Strategy". Centro. Archived from the original on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- "Walsall and Black Country Metro tram link declared dead « Express & Star". Express & Star. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- "Airport Route". Centro. Archived from the original on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- Walker, Jonathan (24 September 2010). "Loans for big city transport schemes back on the agenda". Birmingham Post. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- "Centro in joint call over Tax Increment Financing" (Press release). Centro. 6 October 2010. Archived from the original on 17 October 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- "City metro still on track". Birmingham Post. 13 June 2005.

- "Metro on the wrong track". Birmingham Post. 2 February 2005.

- "Company to study plan for city tube". Birmingham Post. 2 November 2004.

- "Collision between a tram and road vehicle at New Swan Lane Level Crossing on Midland Metro" (PDF). Rail Accident Investigation Branch. June 2007. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

Bibliography

- Boynton, John (2001). Main Line to Metro: Train and tram on the Great Western route: Birmingham Snow Hill – Wolverhampton. Kidderminster: Mid England Books. ISBN 978-0-9522248-9-1.

Further reading

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to West Midlands Metro. |

_May19.jpg.webp)