Moken

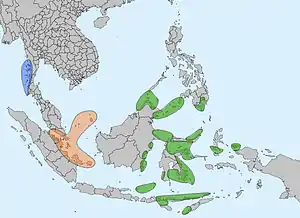

The Moken (also Mawken or Morgan; Burmese: ဆလုံ လူမျိုး; Thai: ชาวเล, romanized: chao le, lit. 'sea people') are an Austronesian people of the Mergui Archipelago, a group of approximately 800 islands claimed by both Burma and Thailand. Most of the 2,000 to 3,000 Moken live a semi-nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle heavily based on the sea, though this is increasingly under threat.

Moken girl | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| ~2000 (2013)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Moken, Thai, Burmese, others | |

| Religion | |

| Traditional religion, Buddhism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Malay, Orang laut, Balinese |

The Moken identify in a common culture, there are 1500 men and 1500 women and speak the Moken language, a distinct Austronesian language. Attempts by both Burma and Thailand to assimilate the Moken into the wider regional culture have met with very limited success. However, the Moken face an uncertain future as their population decreases and their nomadic lifestyle and unsettled legal status leave them marginalized by modern property and immigration laws, maritime conservation and development programs, and tightening border policies.[3][4][5][6]

Nomenclature

The people refer to themselves as Moken. The name is used for all of the Austronesian speaking tribes who inhabit the coast and islands in the Andaman Sea on the west coast of Thailand, the provinces of Satun, Trang, Krabi, Phuket, Phang Nga, and Ranong, up through the Mergui Archipelago of Myanmar. The group includes the Moken proper, the Moklen (Moklem), the Orang Sireh (Betel-leaf People), and the Orang Lanta. The last, the Orang Lanta, are a hybridized group formed when the Malay people settled the Lanta islands where the proto-Malay Orang Sireh had been living. The Moklen are considered to be mostly sedentary with more permanent villages in the provinces of Phang-nga, Phuket, Krabi, and Satun. These individuals also have closer ties to the countries in which they reside as they accept both the nationality and citizenship. Their children are also educated through local schools and are exposed to more mainstream cultural ideas. The Moken residing on the Islands of Surin retain their more traditional methods and lifestyle.[7]

The Burmese call the Moken "selung", "salone", or "chalome".[8] In Thailand they are called "chao le", which can mean people who "live by the sea and pursue a marine livelihood" or those who speak the Austronesian language.[7] Another term that can be used is or "chao nam" ("people of the water"), although these terms are also used loosely to include the Urak Lawoi and even the Orang Laut. In Thailand, acculturated Moken are called "Thai mai" ("new Thais").

The Moken are also called sea gypsies, a generic term that applies to a number of peoples in Southeast Asia. The Urak Lawoi are sometimes classified with the Moken, but they are linguistically and ethnologically distinct, being much more closely related to the Malay people.[9][10]

Way of life

Their knowledge of the sea enables them to live off its fauna and flora by using simple tools such as nets and spears to forage for food, which allows them to impact the environment more minimally than other more intensive forms of subsistence. Furthermore, their frequent movement in kin groups of between two and ten families also allows the land to rest and prevents overuse. Moken are considered hunter-gatherers due to their nomadic lifestyle and lack of material good accumulation. They also believe strongly in the idea that natural resources cannot be owned individually but are rather something that the entire community has access to without restrictions. Their egalitarian society follows into their ancestral worship as they regularly present supernatural beings with food offerings. More recently, they have reached out and begun trading some food (sea cucumbers and edible bird nests) as well as marine products like pearls for other necessities at local markets. Trading and epidemics (cholera and smallpox) also lead to their nomadic lifestyles in order to collect a variety of products to trade and to avoid the spread of deadly diseases. If an epidemic begins to spread, the infected members will remain at the location with a small amount of provisions, while healthy members will depart to a new location. The hope is that the provisions will allow the sick enough time to recuperate while not endangering the rest of the kin group with their sickness. The nomadic lifestyle can also reduce group conflict as affected parties may leave one kin group and enter another to give some distance and allow the feud to die down. After some time has passed and the arguing parties see each other once more, the intensity of the argument will have decreased leading to more amicable relationships.[7]

During the dry north-east monsoon season (when the sea is relatively calm), the Moken live on their boats called kabang, which serve not just as transportation, but also as a kitchen, bedroom, and living area. Previously the Moken used a Kabang koman, "a dug-out boat equipped with a salacca gunwale [where] Salacca is a light wood with a long stem".[7] To construct the boat, the different pieces are fitted into each other with the natural resources the Moken can find on land. The boat's usage was discontinued more than 40 years ago as the salt water eroded the wood within three to sixth months, therefore new techniques were devised to create more robust boats. The kabang last longer and one anthropologist, Jacques Ivanoff, suggests that the boat with its bifurcated bow and stern represent the human body.[7] In monsoon season, which falls between the months of May and October, they set temporary camps on the mainland. During the monsoon season, they build additional boats and forage for food in the forest.

Some of the Burmese Moken are still nomadic people who roam the sea most of their lives; however, much of their traditional life, which is built on the premise of life as outsiders, is under threat.[11]

Aside from ancestor worship, the Moken have no religion.[12][13]

Underwater sight

For most of the human population, underwater vision is very poor for two different reasons. Both the curved cornea and the internal lens of the human fail in an aqueous solution. Unfortunately, this accounts for two thirds of the optical power with air as the medium. In water this processing power is lost, meaning most are left with extremely blurry vision.[14] Moken children, however, are able to see underwater while freediving in order to collect clams, sea cucumbers, and more. They have actually been found to see better underwater than European children as their "special resolution [is] more than twice as good".[15] A Swedish scientist, Anna Gislen, theorized that this was due to constriction of their pupils and accommodation of their visual focus.[16][17] Other than these abilities, the Moken children had regular corneal curvature meaning that their eyes had not evolved to be flatter like many fish nor had their eyes become myopic as their vision on land is still clear.[14] She tested this theory on seventeen Moken children and eighteen European children through sessions involving testing of underwater vision. Gislen's experiment affirmed her hypothesis, and she further discovered that European children could train themselves to develop this same trait. After eleven training sessions over one month, these European children developed underwater visual acuity equal to the Moken children's. At the same time, Gislen also documented that the European children sustained temporary eye irritation ("red eyes") as a result of their underwater dives, unlike the Moken children.[16] Gislen's work highlights that both environmental/behavioral conditioning and evolutionary adaptation are involved in the reported phenomenon of extraordinary aquatic vision in Moken children.

Members of another "sea gypsy" group, the Sama-Bajau, appear to have a number of genetic adaptations to facilitate a lifestyle involving extensive freediving.[18]

Governmental control

The Burmese and Thai governments have made attempts at assimilating the people into their own culture, but these efforts have met with limited success. Thai Moken have been permanently settled in villages located in the Surin Islands (Mu Ko Surin National Park),[19][20] in Phuket Province, on the northwestern coast of Phuket Island, and on the nearby Phi Phi Islands of Krabi Province.[21]

The Andaman Sea off the Tenasserim coast was the subject of keen scrutiny from Burma's regime during the 1990s due to offshore petroleum discoveries by multinational corporations including Unocal, Petronas and others. Reports from the late-1990s told of forced relocation by Burma's military regime of the sea gypsies to mainland sites. It was claimed most of the Salone had been relocated by 1997, which is consistent with a pervasive pattern of forced relocation of suspect ethnic, economic and political groups, conducted throughout Burma during the 1990s.

In Thailand, the Moken have been the target of land grabs by developers contesting their ownership of ancestral lands. Although sea gypsies have resided in Thailand's Andaman coastal provinces for several centuries, they have historically neglected to register official ownership of the land due to their ignorance of legal protocol.[12]

History

There is much speculation as to the historical origins of the Moken people. It is thought that, due to their Austronesian language, they originated in Southern China as agriculturalists 5000–6000 years ago. From there, the Austronesian peoples dispersed and settled various South Asian Islands. It is theorized that the Moken were forced off of these coastal islands into a nomadic lifestyle on the water due to rising sea levels.

2004 Indian Ocean tsunami

The islands the Moken inhabit received much media attention in 2005 during the recovery from the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami. As they are keenly attuned to the ocean, the Moken in some areas knew the tsunami that struck on 26 December 2004 was coming and managed to preserve many lives.[22] However, in the coastal villages of Phang Nga Province, like Tap Tawan, the Moken suffered severe devastation to housing and fishing boats in common with other Moken communities.[23]

Notes

- "The lost world: Myanmar's Mergui Islands". Financial Times. Retrieved 2017-11-10.

- David E. Sopher (1965). "The Sea Nomads: A Study Based on the Literature of the Maritime Boat People of Southeast Asia". Memoirs of the National Museum. 5: 389–403. doi:10.2307/2051635. JSTOR 2051635.

- Some classifications do not include Moken under the Malayan languages, or even under the Aboriginal Malay group of languages. "Ethnologue report for Moken/Moklen" Ethnologue. Moken is considered part of, but isolated within, the (Nuclear) Malayo-Polynesian family, displaying no particular affinities to any other (Nuclear) Malayo-Polynesian language. Moreover, it has undergone strong areal influence from neighbouring Mon–Khmer languages, comparable to, but apparently independently from the Chamic languages.

- "'The ocean is our universe' - Survival International". Survivalinternational. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- "The Moken of Burma and Thailand". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- "The Moken". Projectmoken.com. Retrieved January 8, 2017.

- Arunotai, Narumon (December 20, 2006). "Moken Traditional Knowledge: An Unrecognised Form of Natural Resources Management and Conservation". International Social Science Journal. 58 (187): 139–150. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2451.2006.00599.x.

- Anderson, John (1890). The Selungs of the Mergui Archipelago. London: Trübner & Co. pp. 1–5.

- "Urak Lawoi'". Ethnologue.

- Dr. Supin Wongbusarakum (December 2005). "Urak Lawoi of the Adang Archipelago, Tarutao National Marine Park, Satun Province, Thailand". Archived from the original on 2006-06-28.

- "The South Asian monsoon, past, present and future". The Economist (online: free registration or subscription). June 29, 2019. pp. 45–46 (two sentences). Retrieved 20 August 2019.

Their boat-dwelling descendants live on as the Moken, Orang Suku Laut and Bajau Laut. Today they are marginalised, subjected to ever-tightening pressure by the state to respect borders and come ashore.

- Na Thalang, Jeerawat (12 February 2017). "Sea gypsies turning the tide". Bangkok Post. Retrieved 12 February 2017.

- Revel, Nicole (2013). Songs of Memory in Islands of Southeast Asia. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 201. ISBN 978-1-4438-5280-7.

- Gislén, Anna; Dacke, Marie; Kröger, Ronald H.H; Abrahamsson, Maths; Nilsson, Dan-Eric; Warrant, Eric J (May 2003). "Superior Underwater Vision in a Human Population of Sea Gypsies". Current Biology. 13 (10): 833–836. doi:10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00290-2. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 12747831. S2CID 18731746.

- Gislén, Anna; Warrant, Eric J.; Dacke, Marie; Kröger, Ronald H.H. (October 2006). "Visual training improves underwater vision in children". Vision Research. 46 (20): 3443–3450. doi:10.1016/j.visres.2006.05.004. ISSN 0042-6989. PMID 16806388.

- Gislén, A.; Dacke, M.; Kröger, R.H.H; Abrahamsson, M.; Nilsson, D.-E.; Warrant, E.J. (2003). "Superior Underwater Vision in a Human Population of Sea Gypsies". Current Biology. 13 (10): 833–836. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00290-2. PMID 12747831. S2CID 18731746.

- Travis, J. (2003-05-17). "Children of Sea See Clearly Underwater". Science News. 163 (20): 308–309. doi:10.2307/4014626. JSTOR 4014626. Retrieved 2018-05-06.

- Ilardo, M. A.; Moltke, I.; Korneliussen, T. S.; Cheng, J.; Stern, A. J.; Racimo, F.; de Barros Damgaard, P.; Sikora, M.; Seguin-Orlando, A.; Rasmussen, S.; van den Munckhof, I. C. L.; ter Horst, R.; Joosten, L. A. B.; Netea, M. G.; Salingkat, S.; Nielsen, R.; Willerslev, E. (2018-04-18). "Physiological and Genetic Adaptations to Diving in Sea Nomads". Cell. 173 (3): 569–580.e15. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2018.03.054. PMID 29677510.

- "Environmental, social and cultural settings of the Surin Islands".

- ""Mu Ko Surin National Park" National Park, Wildlife and Plant Conservation Department, Bangkok, Thailand". Archived from the original on June 27, 2014.

- Bauerlein, Monika (November 2005) "Sea change: they outsmarted the tsunami, but Thailand's sea gypsies could be swept away by an even greater force" Mother Jones 30(6): pp. 56–61;

- Leung, Rebecca (25 December 2005). "Sea Gypsies See Signs In The Waves". 60 Minutes. CBS News.

- Jones, Mark (6 May 2005). "Thailand's fisherfolk rebuild after tsunami". Reuters.

Further reading

- Bernatzik, H. A., & Ivanoff, J. (2005). Moken and Semang: 1936–2004, persistence and change. Bangkok: White Lotus. ISBN 974-480-082-8

- Ivanoff, J. (2001). Rings of coral: Moken folktales. Mergui archipelago project, no. 2. Bangkok, Thailand: White Lotus Press. ISBN 974-7534-71-1

- Ivanoff, J. (1999). The Moken boat: symbolic technology. Bangkok: White Lotus Press. ISBN 974-8434-90-7

- Ivanoff, J., Cholmeley, F. N., & Ivanoff, P. (1997). Moken: sea-gypsies of the Andaman Sea, post-war chronicles. Bangkok: Cheney. ISBN 974-8496-65-1

- Lewis, M. B. (1960). Moken texts and word-list; a provisional interpretation. Federation museums journal, v.4. [Kuala Lumpur]: Museums Dept., Federation of Malaya.

- White, W. G. (1922). The sea gypsies of Malaya; an account of the nomadic Mawken people of the Mergui Archipelago with a description of their ways of living, customs, habits, boats, occupations, etc. London: Seeley, Service & Co.

- White, W. G. (1911). An introduction to the Mawken language. Toungoo: S.P.G. Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Moken. |

- Project Moken

- "The Sea Gypsies" (CBS-TV; 60 Minutes; 2005).

- Salons: Sea Gypsies @ Enchanting Myanmar

- Moken: Sea Gypsies @ National Geographic (Subscription Required)

- Moken: Sea Gypsies @ National Geographic (Tsunami Extra)

- Phuket Magazine: The Moken – Traditional Sea Gypsies

- ProjectMaje.org – Burma "Sea Gypsies" Compendium

- Moken language and verbs

- Ethnologue report for Moken

- The Sea Gypsies of Surin Island – Expeditions, Research in Applied Anthropology

- "The Sea Gypsies of Surin Island" by Antonio Graceffo

- images of Moken children underwater

- Moken-Video-NAG

- A reading list of books on the Moken and the Mergui Archipelago

- Moken music, Archive.org