Burmese language

Burmese (Burmese: မြန်မာဘာသာ, MLCTS: mranmabhasa, IPA: [mjəmà bàðà]) is a Sino-Tibetan language spoken in Myanmar where it is an official language and the language of the Bamar people, the country's principal ethnic group. Although the Constitution of Myanmar officially recognizes the English name of the language as the Myanmar language,[3] most English speakers continue to refer to the language as Burmese, after Burma, the previous name for Myanmar. In 2007, it was spoken as a first language by 33 million, primarily the Bamar (Burman) people and related ethnic groups, and as a second language by 10 million, particularly ethnic minorities in Myanmar and neighboring countries. In 2014 the Burmese population was 36.39 million, and has been estimated at 38.2 million as of April 2020.

| Burmese | |

|---|---|

| Myanmar language | |

| မြန်မာစာ (written Burmese) မြန်မာစာစကား (spoken Burmese) | |

| Pronunciation | IPA:[mjəmàzà] [mjəmà zəɡá] |

| Native to | Myanmar |

| Ethnicity | Bamar |

Native speakers | 33 million (2007)[1] Second language: 10 million (no date)[2] |

Sino-Tibetan

| |

Early forms | |

| Burmese alphabet Burmese Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Myanmar Language Commission |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | my |

| ISO 639-2 | bur (B) mya (T) |

| ISO 639-3 | mya – inclusive codeIndividual codes: int – Inthatvn – Tavoyan dialectstco – Taungyo dialectsrki – Rakhine language ("Rakhine")rmz – Marma ("မရမာ") |

| Glottolog | nucl1310 |

| Linguasphere | 77-AAA-a |

| |

Burmese is a tonal, pitch-register, and syllable-timed language,[4] largely monosyllabic and analytic, with a subject–object–verb word order. It is a member of the Lolo-Burmese grouping of the Sino-Tibetan language family. The Burmese alphabet is ultimately descended from a Brahmic script, either Kadamba or Pallava.

Classification

Burmese belongs to the Southern Burmish branch of the Sino-Tibetan languages, of which Burmese is the most widely spoken of the non-Sinitic languages.[5] Burmese was the fifth of the Sino-Tibetan languages to develop a writing system, after Chinese characters, the Pyu script, the Tibetan alphabet, and the Tangut script.[6]

Dialects

The majority of Burmese speakers, who live throughout the Irrawaddy River Valley, use a number of largely similar dialects, while a minority speak non-standard dialects found in the peripheral areas of the country. These dialects include:

- Tanintharyi Region: Merguese (Myeik, Beik), Tavoyan (Dawei), and Palaw

- Magway Region: Yaw

- Shan State: Intha, Taungyo, and Danu

Arakanese (Rakhine) in Rakhine State and Marma in Bangladesh are also sometimes considered dialects of Burmese and sometimes as separate languages.

Despite vocabulary and pronunciation differences, there is mutual intelligibility among Burmese dialects, as they share a common set of tones, consonant clusters, and written script. However, several Burmese dialects differ substantially from standard Burmese with respect to vocabulary, lexical particles, and rhymes.

Irrawaddy River valley

Spoken Burmese is remarkably uniform among Burmese speakers,[7] particularly those living in the Irrawaddy valley, all of whom use variants of Standard Burmese. The standard dialect of Burmese (the Mandalay-Yangon dialect continuum) comes from the Irrawaddy River valley. Regional differences between speakers from Upper Burma (e.g., Mandalay dialect), called anya tha (အညာသား) and speakers from Lower Burma (e.g., Yangon dialect), called auk tha (အောက်သား), largely occur in vocabulary choice, not in pronunciation. Minor lexical and pronunciation differences exist throughout the Irrawaddy River valley.[8] For instance, for the term ဆွမ်း, "food offering [to a monk]", Lower Burmese speakers use [sʰʊ́ɰ̃] instead of [sʰwáɰ̃], which is the pronunciation used in Upper Burma.

The standard dialect is represented by the Yangon dialect because of the modern city's media influence and economic clout. In the past, the Mandalay dialect represented standard Burmese. The most noticeable feature of the Mandalay dialect is its use of the first person pronoun ကျွန်တော်, kya.nau [tɕənɔ̀] by both men and women, whereas in Yangon, the said pronoun is used only by male speakers while ကျွန်မ, kya.ma. [tɕəma̰] is used by female speakers. Moreover, with regard to kinship terminology, Upper Burmese speakers differentiate the maternal and paternal sides of a family, whereas Lower Burmese speakers do not.

The Mon language has also influenced subtle grammatical differences between the varieties of Burmese spoken in Lower and Upper Burma.[9] In Lower Burmese varieties, the verb ပေး ('to give') is colloquially used as a permissive causative marker, like in other Southeast Asian languages, but unlike in other Tibeto-Burman languages.[9] This usage is hardly used in Upper Burmese varieties, and is considered a sub-standard construct.[9]

Outside the Irrawaddy basin

More distinctive non-standard varieties emerge as one moves farther away from the Irrawaddy River valley toward peripheral areas of the country. These varieties include the Yaw, Palaw, Myeik (Merguese), Tavoyan and Intha dialects. Despite substantial vocabulary and pronunciation differences, there is mutual intelligibility among most Burmese dialects. Dialects in Tanintharyi Region, including Palaw, Merguese, and Tavoyan, are especially conservative in comparison to Standard Burmese. The Tavoyan and Intha dialects have preserved the /l/ medial, which is otherwise only found in Old Burmese inscriptions. They also often reduce the intensity of the glottal stop. Myeik has 250,000 speakers[10] while Tavoyan has 400,000. The grammatical constructs of Burmese dialects in Southern Myanmar show greater Mon influence than Standard Burmese.[9]

The most pronounced feature of the Arakanese language of Rakhine State is its retention of the [ɹ] sound, which has become [j] in standard Burmese. Moreover, Arakanese features a variety of vowel differences, including the merger of the ဧ [e] and ဣ [i] vowels. Hence, a word like "blood" သွေး is pronounced [θwé] in standard Burmese and [θwí] in Arakanese.

History

The Burmese language's early forms include Old Burmese and Middle Burmese. Old Burmese dates from the 11th to the 16th century (Pagan to Ava dynasties); Middle Burmese from the 16th to the 18th century (Toungoo to early Konbaung dynasties); modern Burmese from the mid-18th century to the present. Word order, grammatical structure, and vocabulary have remained markedly stable well into Modern Burmese, with the exception of lexical content (e.g., function words).[11][12]

Old Burmese

The earliest attested form of the Burmese language is called Old Burmese, dating to the 11th and 12th century stone inscriptions of Pagan. The earliest evidence of the Burmese alphabet is dated to 1035, while a casting made in the 18th century of an old stone inscription points to 984.[13]

Owing to the linguistic prestige of Old Mon in the Pagan Kingdom era, Old Burmese borrowed a substantial corpus of vocabulary from Pali via the Mon language.[9] These indirect borrowings can be traced back to orthographic idiosyncrasies in these loanwords, such as the Burmese word "to worship," which is spelt ပူဇော် (pūjo) instead of ပူဇာ (pūjā), as would be expected by the original Pali orthography.[9]

Middle Burmese

The transition to Middle Burmese occurred in the 16th century.[11] The transition to Middle Burmese included phonological changes (e.g. mergers of sound pairs that were distinct in Old Burmese) as well as accompanying changes in the underlying orthography.[11]

From the 1500s onward, Burmese kingdoms saw substantial gains in the populace's literacy rate, which manifested itself in greater participation of laymen in scribing and composing legal and historical documents, domains that were traditionally the domain of Buddhist monks, and drove the ensuing proliferation of Burmese literature, both in terms of genres and works.[14] During this period, the Burmese script began employing cursive-style circular letters typically used in palm-leaf manuscripts, as opposed to the traditional square block-form letters used in earlier periods.[14] The orthographic conventions used in written Burmese today can largely be traced back to Middle Burmese.

Modern Burmese

Modern Burmese emerged in the mid-18th century. By this time, male literacy in Burma stood at nearly 50%, which enabled the wide circulation of legal texts, royal chronicles, and religious texts.[14] A major reason for the uniformity of the Burmese language was the near-universal presence of Buddhist monasteries (called kyaung) in Burmese villages. These kyaung served as the foundation of the pre-colonial monastic education system, which fostered uniformity of the language throughout the Upper Irrawaddy valley, the traditional homeland of Burmese speakers. The 1891 Census of India, conducted five years after the annexation of the entire Konbaung Kingdom, found that the former kingdom had an "unusually high male literacy" rate of 62.5% for Upper Burmans aged 25 and above. For all of British Burma, the literacy rate was 49% for men and 5.5% for women (by contrast, British India more broadly had a male literacy rate of 8.44%).[15]

The expansion of the Burmese language into Lower Burma also coincided with the emergence of Modern Burmese. As late as the mid-1700s, Mon, an Austroasiatic language, was the principal language of Lower Burma, employed by the Mon people who inhabited the region. Lower Burma's shift from Mon to Burmese was accelerated by the Burmese-speaking Konbaung Dynasty's victory over the Mon-speaking Restored Hanthawaddy Kingdom in 1757. By 1830, an estimated 90% of the population in Lower Burma self-identified as Burmese-speaking Bamars; huge swaths of former Mon-speaking territory, from the Irrawaddy Delta to upriver in the north, spanning Bassein (now Pathein) and Rangoon (now Yangon) to Tharrawaddy, Toungoo, Prome (now Pyay), and Henzada (now Hinthada), were now Burmese-speaking.[16][14] The language shift has been ascribed to a combination of population displacement, intermarriage, and voluntary changes in self-identification among increasingly Mon-Burmese bilingual populations in the region.[14][16]

Standardized tone marking in written Burmese was not achieved until the 18th century. From the 19th century onward, orthographers created spellers to reform Burmese spelling, because of ambiguities that arose over transcribing sounds that had been merged.[17] British rule saw continued efforts to standardize Burmese spelling through dictionaries and spellers.

Britain's gradual annexation of Burma throughout the 19th century, in addition to concomitant economic and political instability in Upper Burma (e.g., increased tax burdens from the Burmese crown, British rice production incentives, etc.) also accelerated the migration of Burmese speakers from Upper Burma into Lower Burma.[18] British rule in Burma eroded the strategic and economic importance of the Burmese language; Burmese was effectively subordinated to the English language in the colonial educational system, especially in higher education.[8]

In the 1930s, the Burmese language saw a linguistic revival, precipitated by the establishment of an independent University of Rangoon in 1920 and the inception of a Burmese language major at the university by Pe Maung Tin, modeled on Anglo Saxon language studies at the University of Oxford.[8] Student protests in December of that year, triggered by the introduction of English into matriculation examinations, fueled growing demand for Burmese to become the medium of education in British Burma; a short-lived but symbolic parallel system of "national schools" that taught in Burmese, was subsequently launched.[8] The role and prominence of the Burmese language in public life and institutions was championed by Burmese nationalists, intertwined with their demands for greater autonomy and independence from the British in the lead-up to the independence of Burma in 1948.[8]

The 1948 Constitution of Burma prescribed Burmese as the official language of the newly independent nation. The Burma Translation Society and Rangoon University's Department of Translation and Publication were established in 1947 and 1948, respectively, with the joint goal of modernizing the Burmese language in order to replace English across all disciplines.[8] Anti-colonial sentiment throughout the early post-independence era led to a reactionary switch from English to Burmese as the national medium of education, a process that was accelerated by the Burmese Way to Socialism.[8] In August 1963, the socialist Union Revolutionary Government established the Literary and Translation Commission (the immediate precursor of the Myanmar Language Commission) to standardize Burmese spelling, diction, composition, and terminology. The latest spelling authority, named the Myanma Salonpaung Thatpon Kyan (မြန်မာ စာလုံးပေါင်း သတ်ပုံ ကျမ်း), was compiled in 1978 by the commission.[17]

Registers

Burmese is a diglossic language with two distinguishable registers (or diglossic varieties):[19]

- Literary High (H) form[20] (မြန်မာစာ mranma ca): the high variety (formal and written), used in literature (formal writing), newspapers, radio broadcasts, and formal speeches

- Spoken Low (L) form[20] (မြန်မာစကား mranma ca.ka:): the low variety (informal and spoken), used in daily conversation, television, comics and literature (informal writing)

The literary form of Burmese retains archaic and conservative grammatical structures and modifiers (including particles, markers, and pronouns) no longer used in the colloquial form.[19] Literary Burmese, which has not changed significantly since the 13th century, is the register of Burmese taught in schools.[8][21] In most cases, the corresponding grammatical markers in the literary and spoken forms are totally unrelated to each other.[22] Examples of this phenomenon include the following lexical terms:

- "this" (pronoun): HIGH ဤ i → LOW ဒီ di

- "that" (pronoun): HIGH ထို htui → LOW ဟို hui

- "at" (postposition): HIGH ၌ hnai. [n̥aɪʔ] → LOW မှာ hma [m̥à]

- plural (marker): HIGH များ mya: → LOW တွေ twe

- possessive (marker): HIGH ၏ i. → LOW ရဲ့ re.

- "and" (conjunction): HIGH နှင့် hnang. → LOW နဲ့ ne.

- "if" (conjunction): HIGH လျှင် hlyang → LOW ရင် rang

Historically the literary register was preferred for written Burmese on the grounds that "the spoken style lacks gravity, authority, dignity". In the mid-1960s, some Burmese writers spearheaded efforts to abandon the literary form, asserting that the spoken vernacular form ought to be used.[23][24] Some Burmese linguists such as Minn Latt, a Czech academic, proposed moving away from the high form of Burmese altogether.[25] Although the literary form is heavily used in written and official contexts (literary and scholarly works, radio news broadcasts, and novels), the recent trend has been to accommodate the spoken form in informal written contexts.[17] Nowadays, television news broadcasts, comics, and commercial publications use the spoken form or a combination of the spoken and simpler, less ornate formal forms.[19]

The following sample sentence reveals that differences between literary and spoken Burmese mostly occur in grammatical particles:

| noun | verb | part. | noun | part. | adj. | part. | verb | part. | part. | part. | |

| Literary (HIGH) |

ရှစ်လေးလုံးအရေးအခင်း hracle:lum:a.re:a.hkang: | ဖြစ် hprac | သောအခါက sau:a.hkaka. | လူ lu | ဦးရေ u:re | ၃၀၀၀ 3000 | မျှ hmya. | သေဆုံး sehcum: | ခဲ့ hkai. | ကြ kra. | သည်။ sany |

| Spoken (LOW) |

တုံးက tum:ka. | အယောက် a.yauk | လောက် lauk | သေ se | - | တယ်။ tai | |||||

| Gloss | The Four Eights Uprising | happen | when | people | measure word | 3,000 | approximately | die | past tense | plural marker | sentence final |

Burmese has politeness levels and honorifics that take the speaker's status and age in relation to the audience into account. The particle ပါ pa is frequently used after a verb to express politeness.[26] Moreover, Burmese pronouns relay varying degrees of deference or respect.[27] In many instances, polite speech (e.g., addressing teachers, officials, or elders) employs feudal-era third person pronouns or kinship terms in lieu of first- and second-person pronouns.[28][29] Furthermore, with regard to vocabulary choice, spoken Burmese clearly distinguishes the Buddhist clergy (monks) from the laity (householders), especially when speaking to or about bhikkhus (monks).[30] The following are examples of varying vocabulary used for Buddhist clergy and for laity:

- "sleep" (verb): ကျိန်း kyin: [tɕẽ́ʲ] for monks vs. အိပ် ip [eʲʔ] for laity

- "die" (verb): ပျံတော်မူ pyam tau mu [pjã̀ dɔ̀ mù] for monks vs. သေ se [t̪è] for laity

Vocabulary

Burmese primarily has a monosyllabic received Sino-Tibetan vocabulary. Nonetheless, many words, especially loanwords from Indo-European languages like English, are polysyllabic, and others, from Mon, an Austroasiatic language, are sesquisyllabic.[31] Burmese loanwords are overwhelmingly in the form of nouns.[31]

Historically, Pali, the liturgical language of Theravada Buddhism, had a profound influence on Burmese vocabulary. Burmese has readily adopted words of Pali origin; this may be due to phonotactic similarities between the two languages, alongside the fact that the script used for Burmese can be used to reproduce Pali spellings with complete accuracy.[32] Pali loanwords are often related to religion, government, arts, and science.[32]

Burmese loanwords from Pali primarily take four forms:

- Direct loan: direct import of Pali words with no alteration in orthography

- "life": Pali ဇီဝ jiva → Burmese ဇီဝ jiva

- Abbreviated loan: import of Pali words with accompanied syllable reduction and alteration in orthography (usually by means of a placing a diacritic, called athat အသတ် (lit. 'nonexistence') atop the last letter in the syllable to suppress the consonant's inherent vowel[33]

- "karma": Pali ကမ္မ kamma → Burmese ကံ kam

- "dawn": Pali အရုဏ aruṇa → Burmese အရုဏ် aruṇ

- "merit": Pali ကုသလ kusala → Burmese ကုသိုလ် kusuil

- Double loan: adoption of two different terms derived from the same Pali word[32]

- Pali မာန māna → Burmese မာန [màna̰] ('arrogance') and မာန် [mã̀] ('pride')

- Hybrid loan (e.g., neologisms or calques): construction of compounds combining native Burmese words with Pali or combine Pali words:[34]

- "airplane": လေယာဉ်ပျံ [lè jɪ̀m bjã̀], lit. 'air machine fly', ← လေ (native Burmese, 'air') + ယာဉ် (from Pali yana, 'vehicle') + ပျံ (native Burmese word, 'fly')[34]

Burmese has also adapted numerous words from Mon, traditionally spoken by the Mon people, who until recently formed the majority in Lower Burma. Most Mon loanwords are so well assimilated that they are not distinguished as loanwords, as Burmese and Mon were used interchangeably for several centuries in pre-colonial Burma.[35] Mon loans are often related to flora, fauna, administration, textiles, foods, boats, crafts, architecture, and music.[17]

As a natural consequence of British rule in Burma, English has been another major source of vocabulary, especially with regard to technology, measurements, and modern institutions. English loanwords tend to take one of three forms:

- Direct loan: adoption of an English word, adapted to the Burmese phonology[36]

- "democracy": English democracy → Burmese ဒီမိုကရေစီ

- Neologism or calque: translation of an English word using native Burmese constituent words[37]

- "human rights": English 'human rights' → Burmese လူ့အခွင့်အရေး (လူ့ 'human' + အခွင့်အရေး 'rights')

- Hybrid loan: construction of compound words by joining native Burmese words to English words[38]

- 'to sign': ဆိုင်းထိုး [sʰã́ɪ̃ tʰó] ← ဆိုင်း (English, sign) + ထိုး (native Burmese, 'inscribe').

To a lesser extent, Burmese has also imported words from Sanskrit (religion), Hindi (food, administration, and shipping), and Chinese (games and food).[17] Burmese has also imported a handful of words from other European languages such as Portuguese.

Here is a sample of loan words found in Burmese:

- suffering: ဒုက္ခ [dowʔkʰa̰], from Pali dukkha

- radio: ရေဒီယို [ɹèdìjò], from English radio

- method: စနစ် [sənɪʔ], from Mon

- eggroll: ကော်ပြန့် [kɔ̀pjã̰], from Hokkien 潤餅 (jūn-piáⁿ)

- wife: ဇနီး [zəní], from Hindi jani

- noodle: ခေါက်ဆွဲ [kʰaʊʔ sʰwɛ́], from Shan ၶဝ်ႈသွႆး [kʰāu sʰɔi]

- foot (unit of measurement): ပေ [pè], from Portuguese pé

- flag: အလံ [əlã̀], Arabic: علم ʿalam

- storeroom: ဂိုဒေါင် [ɡòdã̀ʊ̃], from Malay gudang

Since the end of British rule, the Burmese government has attempted to limit usage of Western loans (especially from English) by coining new words (neologisms). For instance, for the word "television," Burmese publications are mandated to use the term ရုပ်မြင်သံကြား (lit. 'see picture, hear sound') in lieu of တယ်လီဗီးရှင်း, a direct English transliteration.[39] Another example is the word "vehicle", which is officially ယာဉ် [jɪ̃̀] (derived from Pali) but ကား [ká] (from English car) in spoken Burmese. Some previously common English loanwords have fallen out of use with the adoption of neologisms. An example is the word "university", formerly ယူနီဗာစတီ jùnìbàsətì], from English university, now တက္ကသိုလ် [tɛʔkət̪ò], a Pali-derived neologism recently created by the Burmese government and derived from the Pali spelling of Taxila (တက္ကသီလ Takkasīla), an ancient university town in modern-day Pakistan.[39]

Some words in Burmese may have many synonyms, each having certain usages, such as formal, literary, colloquial, and poetic. One example is the word "moon", which can be လ la̰ (native Tibeto-Burman), စန္ဒာ/စန်း [sàndà]/[sã́] (derivatives of Pali canda 'moon'), or သော်တာ [t̪ɔ̀ dà] (Sanskrit).[40]

Phonology

Consonants

The consonants of Burmese are as follows:

| Bilabial | Dental | Alveolar | Post-al. /Palatal |

Velar | Laryngeal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | voiced | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||

| voiceless | m̥ | n̥ | ɲ̊ | ŋ̊ | |||

| Stop | Voiced | b | d | dʒ | ɡ | ||

| plain | p | t | tʃ | k | ʔ | ||

| aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | tʃʰ | kʰ | |||

| Fricative | voiced | ð ([d̪ð~d̪]) | z | ||||

| voiceless | θ ([t̪θ~t̪]) | s | ʃ | ||||

| aspirated | sʰ | h | |||||

| Approximant | voiced | l | j | w | |||

| voiceless | l̥ | ʍ | |||||

According to Jenny & San San Hnin Tun (2016:15), contrary to their use of symbols θ and ð, consonants of သ are dental stops (/t̪, d̪/), rather than fricatives (/θ, ð/) or affricates.[43]

An alveolar /ɹ/ can occur as an alternate of /j/ in some loanwords.

Vowels

The vowels of Burmese are:

| Monophthongs | Diphthongs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Front | Central | Back | Front offglide | Back offglide | |

| Close | i | u | |||

| Close-mid | e | ə | o | ei | ou |

| Open-mid | ɛ | ɔ | |||

| Open | a | ai | au | ||

The monophthongs /e/, /o/, /ə/ and /ɔ/ occur only in open syllables (those without a syllable coda); the diphthongs /ei/, /ou/, /ai/ and /au/ occur only in closed syllables (those with a syllable coda). /ə/ only occurs in a minor syllable, and is the only vowel that is permitted in a minor syllable (see below).

The close vowels /i/ and /u/ and the close portions of the diphthongs are somewhat mid-centralized ([ɪ, ʊ]) in closed syllables, i.e. before /ɰ̃/ and /ʔ/. Thus နှစ် /n̥iʔ/ ('two') is phonetically [n̥ɪʔ] and ကြောင် /tɕàũ/ ('cat') is phonetically [tɕàʊ̃].

Tones

Burmese is a tonal language, which means phonemic contrasts can be made on the basis of the tone of a vowel. In Burmese, these contrasts involve not only pitch, but also phonation, intensity (loudness), duration, and vowel quality. However, some linguists consider Burmese a pitch-register language like Shanghainese.[44]

There are four contrastive tones in Burmese. In the following table, the tones are shown marked on the vowel /a/ as an example.

| Tone | Burmese | IPA (shown on a) | Symbol (shown on a) | Phonation | Duration | Intensity | Pitch |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | နိမ့်သံ | [aː˧˧˦] | à | normal | medium | low | low, often slightly rising[45] |

| High | တက်သံ | [aː˥˥˦] | á | sometimes slightly breathy | long | high | high, often with a fall before a pause[45] |

| Creaky | သက်သံ | [aˀ˥˧] | a̰ | tense or creaky, sometimes with lax glottal stop | medium | high | high, often slightly falling[45] |

| Checked | တိုင်သံ | [ăʔ˥˧] | aʔ | centralized vowel quality, final glottal stop | short | high | high (in citation; can vary in context)[45] |

For example, the following words are distinguished from each other only on the basis of tone:

- Low ခါ /kʰà/ "shake"

- High ခါး /kʰá/ "be bitter"

- Creaky ခ /kʰa̰/ "to wait upon; to attend on"

- Checked ခတ် /kʰaʔ/ "to beat; to strike"

In syllables ending with /ɰ̃/, the checked tone is excluded:

- Low ခံ /kʰàɰ̃/ "undergo"

- High ခန်း /kʰáɰ̃/ "dry up (usually a river)"

- Creaky ခန့် /kʰa̰ɰ̃/ "appoint"

In spoken Burmese, some linguists classify two real tones (there are four nominal tones transcribed in written Burmese), "high" (applied to words that terminate with a stop or check, high-rising pitch) and "ordinary" (unchecked and non-glottal words, with falling or lower pitch), with those tones encompassing a variety of pitches.[46] The "ordinary" tone consists of a range of pitches. Linguist L. F. Taylor concluded that "conversational rhythm and euphonic intonation possess importance" not found in related tonal languages and that "its tonal system is now in an advanced state of decay."[47][48]

Syllable structure

The syllable structure of Burmese is C(G)V((V)C), which is to say the onset consists of a consonant optionally followed by a glide, and the rime consists of a monophthong alone, a monophthong with a consonant, or a diphthong with a consonant. The only consonants that can stand in the coda are /ʔ/ and /ɰ̃/. Some representative words are:

- CV မယ် /mɛ̀/ (title for young women)

- CVC မက် /mɛʔ/ 'crave'

- CGV မြေ /mjè/ 'earth'

- CGVC မျက် /mjɛʔ/ 'eye'

- CVVC မောင် /màʊɰ̃/ (term of address for young men)

- CGVVC မြောင်း /mjáʊɰ̃/ 'ditch'

A minor syllable has some restrictions:

- It contains /ə/ as its only vowel

- It must be an open syllable (no coda consonant)

- It cannot bear tone

- It has only a simple (C) onset (no glide after the consonant)

- It must not be the final syllable of the word

Some examples of words containing minor syllables:

- ခလုတ် /kʰə.loʊʔ/ 'switch, button'

- ပလွေ /pə.lwè/ 'flute'

- သရော် /θə.jɔ̀/ 'mock'

- ကလက် /kə.lɛʔ/ 'be wanton'

- ထမင်းရည် /tʰə.mə.jè/ 'rice-water'

Writing system

The Burmese alphabet consists of 33 letters and 12 vowels and is written from left to right. It requires no spaces between words, although modern writing usually contains spaces after each clause to enhance readability. Characterized by its circular letters and diacritics, the script is an abugida, with all letters having an inherent vowel အ a. [a̰] or [ə]. The consonants are arranged into six consonant groups (called ဝဂ် based on articulation, like other Brahmi scripts. Tone markings and vowel modifications are written as diacritics placed to the left, right, top, and bottom of letters.[17]

Orthographic changes postceded shifts in phonology (such as the merging of the [-l-] and [-ɹ-] medials) rather than transformations in Burmese grammatical structure and phonology, which by contrast, has remained stable between Old Burmese and modern Burmese.[17] For example, during the Pagan era, the medial [-l-] ္လ was transcribed in writing, which has been replaced by medials [-j-] ျ and [-ɹ-] ြ in modern Burmese (e.g. "school" in old Burmese က္လောင် [klɔŋ] → ကျောင်း [tɕã́ʊ̃] in modern Burmese).[49] Likewise, written Burmese has preserved all nasalized finals [-n, -m, -ŋ], which have merged to [-ɰ̃] in spoken Burmese. (The exception is [-ɲ], which, in spoken Burmese, can be one of many open vowels [i, e, ɛ]. Similarly, other consonantal finals [-s, -p, -t, -k] have been reduced to [-ʔ]. Similar mergers are seen in other Sino-Tibetan languages like Shanghainese, and to a lesser extent, Cantonese.

Written Burmese dates to the early Pagan period. British colonial period scholars believed that the Burmese script was developed c. 1058 from the Mon script.[50] However, more recent evidence has shown that the Burmese script has been in use at least since 1035 (perhaps as early as 984), while the earliest Burma Mon script, which is different from the Thailand Mon script, dates to 1093.[51] The Burmese script may have been sourced from the Pyu script.[51] (Both Mon and Pyu scripts are derivatives of the Brahmi script.) Burmese orthography originally followed a square block format, but the cursive format took hold from the 17th century when increased literacy and the resulting explosion of Burmese literature led to the wider use of palm leaves and folded paper known as parabaiks (ပုရပိုက်).[52]

Grammar

The basic word order of the Burmese language is subject-object-verb. Pronouns in Burmese vary according to the gender and status of the audience. Burmese is monosyllabic (i.e., every word is a root to which a particle but not another word may be prefixed).[53] Sentence structure determines syntactical relations and verbs are not conjugated. Instead they have particles suffixed to them. For example, the verb "to eat," စား ca: [sà] is itself unchanged when modified.

Adjectives

Burmese does not have adjectives per se. Rather, it has verbs that carry the meaning "to be X", where X is an English adjective. These verbs can modify a noun by means of the grammatical particle တဲ့ tai. [dɛ̰] in colloquial Burmese (literary form: သော sau: [t̪ɔ́], which is suffixed as follows:

- Colloquial: ချောတဲ့လူ hkyau: tai. lu [tɕʰɔ́ dɛ̰ lù]

- Formal: ချောသောလူ hkyau: so: lu

- Gloss: "beautiful" + adjective particle + 'person'

Adjectives may also form a compound with the noun (e.g. လူချော lu hkyau: [lù tɕʰɔ́] 'person' + 'be beautiful').

Comparatives are usually ordered: X + ထက်ပို htak pui [tʰɛʔ pò] + adjective, where X is the object being compared to. Superlatives are indicated with the prefix အ a. [ʔə] + adjective + ဆုံး hcum: [zṍʊ̃].

Numerals follow the nouns they modify. Moreover, numerals follow several pronunciation rules that involve tone changes (low tone → creaky tone) and voicing shifts depending on the pronunciation of surrounding words. A more thorough explanation is found on Burmese numerals.

Verbs

The roots of Burmese verbs are almost always suffixed with at least one particle which conveys such information as tense, intention, politeness, mood, etc. Many of these particles also have formal/literary and colloquial equivalents. In fact, the only time in which no particle is attached to a verb is in imperative commands.

The most commonly used verb particles and their usage are shown below with an example verb root စား ca: [sá] ('to eat'). Alone, the statement စား is imperative.

The suffix တယ် tai [dɛ̀] (literary form: သည် sany [d̪ì] can be viewed as a particle marking the present tense and/or a factual statement:

- စားတယ် ca: tai [sá dɛ̀] ('I eat')

The suffix ခဲ့ hkai. [ɡɛ̰] denotes that the action took place in the past. However, this particle is not always necessary to indicate the past tense such that it can convey the same information without it. But to emphasize that the action happened before another event that is also currently being discussed, the particle becomes imperative. Note that the suffix တယ် tai [dɛ̀] in this case denotes a factual statement rather than the present tense:

- စားခဲ့တယ် ca: hkai. tai [sá ɡɛ̰ dɛ̀] ('I ate')

The particle နေ ne [nè] is used to denote an action in progression. It is equivalent to the English '-ing'"

- စားနေတယ် ca: ne tai [sá nè dɛ̀] ('I am eating')

This particle ပြီ pri [bjì], which is used when an action that had been expected to be performed by the subject is now finally being performed, has no equivalent in English. So in the above example, if someone had been expecting the subject to eat, and the subject has finally started eating, the particle ပြီ is used as follows:

- (စ)စားပြီ (ca.) ca: pri [(sə) sá bjì] ('I am [now] eating')

The particle မယ် mai [mɛ̀] (literary form: မည် many [mjì] is used to indicate the future tense or an action which is yet to be performed:

- စားမယ် ca: mai [sá mɛ̀] ('I will eat')

The particle တော့ tau. [dɔ̰] is used when the action is about to be performed immediately when used in conjunction with မယ်. Therefore it could be termed as the "immediate future tense particle".

- စားတော့မယ် ca: tau. mai [sá dɔ̰ mɛ̀] ('I'm going to eat [right away]')

When တော့ is used alone, however, it is imperative:

- စားတော့ ca: tau. [sá dɔ̰] ('eat [now]')

Verbs are negated by the particle မ ma. [mə], which is prefixed to the verb. Generally speaking, other particles are suffixed to that verb, along with မ.

The verb suffix particle နဲ့ nai. [nɛ̰] (literary form: နှင့် hnang. [n̥ɪ̰̃] indicates a command:

- မစားနဲ့ ma.ca: nai. [məsá nɛ̰] ('don't eat')

The verb suffix particle ဘူး bhu: [bú] indicates a statement:

- မစားဘူး ma.ca: bhu: [məsá bú] ('[I] don't eat')

Nouns

Nouns in Burmese are pluralized by suffixing the particle တွေ twe [dè] (or [tè] if the word ends in a glottal stop) in colloquial Burmese or များ mya: [mjà] in formal Burmese. The particle တို့ (tou. [to̰], which indicates a group of persons or things, is also suffixed to the modified noun. An example is below:

- မြစ် mrac [mjɪʔ] "river"

- မြစ်တွေ mrac twe [mjɪʔ tè] ('rivers' [colloquial])

- မြစ်များ mrac mya: [mjɪʔ mjá] ('rivers' [formal])

- မြစ်တို့ mrac tou: [mjɪʔ to̰] ('rivers')

Plural suffixes are not used when the noun is quantified with a number.

"five children" ကလေး ၅ ယောက် hka.le: nga: yauk /kʰəlé ŋá jaʊʔ/ child five classifier

Although Burmese does not have grammatical gender (e.g. masculine or feminine nouns), a distinction is made between the sexes, especially in animals and plants, by means of suffix particles. Nouns are masculinized with the following particles: ထီး hti: [tʰí], ဖ hpa [pʰa̰], or ဖို hpui [pʰò], depending on the noun, and feminized with the particle မ ma. [ma̰]. Examples of usage are below:

- ကြောင်ထီး kraung hti: [tɕã̀ʊ̃ tʰí] "male cat"

- ကြောင်မ kraung ma. [tɕã̀ʊ̃ ma̰] "female cat"

- ကြက်ဖ krak hpa. [tɕɛʔ pʰa̰] "rooster/cock"

- ထန်းဖို htan: hpui [tʰã́ pʰò] "male toddy palm plant"

Numerical classifiers

Like its neighboring languages such as Thai, Bengali, and Chinese, Burmese uses numerical classifiers (also called measure words) when nouns are counted or quantified. This approximately equates to English expressions such as "two slices of bread" or "a cup of coffee". Classifiers are required when counting nouns, so ကလေး ၅ hka.le: nga: [kʰəlé ŋà] (lit. 'child five') is incorrect, since the measure word for people ယောက် yauk [jaʊʔ] is missing; it needs to suffix the numeral.

The standard word order of quantified words is: quantified noun + numeral adjective + classifier, except in round numbers (numbers that end in zero), in which the word order is flipped, where the quantified noun precedes the classifier: quantified noun + classifier + numeral adjective. The only exception to this rule is the number 10, which follows the standard word order.

Measurements of time, such as "hour," နာရီ "day," ရက် or "month," လ do not require classifiers.

Below are some of the most commonly used classifiers in Burmese.

| Burmese | MLC | IPA | Usage | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ယောက် | yauk | [jaʊʔ] | for people | Used in informal context |

| ဦး | u: | [ʔú] | for people | Used in formal context and also used for monks and nuns |

| ပါး | pa: | [bá] | for people | Used exclusively for monks and nuns of the Buddhist order |

| ကောင် | kaung | [kã̀ʊ̃] | for animals | |

| ခု | hku. | [kʰṵ] | general classifier | Used with almost all nouns except for animate objects |

| လုံး | lum: | [lṍʊ̃] | for round objects | |

| ပြား | pra: | [pjá] | for flat objects | |

| စု | cu. | [sṵ] | for groups | Can be [zṵ]. |

Particles

The Burmese language makes prominent usage of particles (called ပစ္စည်း in Burmese), which are untranslatable words that are suffixed or prefixed to words to indicate the level of respect, grammatical tense, or mood. According to the Myanmar–English Dictionary (1993), there are 449 particles in the Burmese language. For example, စမ်း [sã́] is a grammatical particle used to indicate the imperative mood. While လုပ်ပါ ('work' + particle indicating politeness) does not indicate the imperative, လုပ်စမ်းပါ ('work' + particle indicating imperative mood + particle indicating politeness) does. Particles may be combined in some cases, especially those modifying verbs.

Some particles modify the word's part of speech. Among the most prominent of these is the particle အ Burmese pronunciation: [[Help:IPA/Burmese|ə]], which is prefixed to verbs and adjectives to form nouns or adverbs. For instance, the word ဝင် means "to enter," but combined with အ, it means "entrance" အဝင်. Moreover, in colloquial Burmese, there is a tendency to omit the second အ in words that follow the pattern အ + noun/adverb + အ + noun/adverb, like အဆောက်အအုံ, which is pronounced [əsʰaʊʔ ú] and formally pronounced [əsʰaʊʔ əõ̀ʊ̃].

Pronouns

Subject pronouns begin sentences, though the subject is generally omitted in the imperative forms and in conversation. Grammatically speaking, subject marker particles က [ɡa̰] in colloquial, သည် [t̪ì] in formal) must be attached to the subject pronoun, although they are also generally omitted in conversation. Object pronouns must have an object marker particle ကို [ɡò] in colloquial, အား [á] in formal) attached immediately after the pronoun. Proper nouns are often substituted for pronouns. One's status in relation to the audience determines the pronouns used, with certain pronouns used for different audiences.

Polite pronouns are used to address elders, teachers, and strangers, through the use of feudal-era third person pronouns in lieu of first- and second-person pronouns. In such situations, one refers to oneself in third person: ကျွန်တော် kya. nau [tɕənɔ̀] for men and ကျွန်မ kya. ma. [tɕəma̰] for women, both meaning "your servant", and refer to the addressee as မင်း min [mɪ̃́] ('your highness'), ခင်ဗျား khang bya: [kʰəmjá] ('master, lord') (from Burmese သခင်ဘုရား 'lord master') or ရှင် hrang [ʃɪ̃̀] "ruler/master".[54] So ingrained are these terms in the daily polite speech that people use them as the first and second person pronouns without giving a second thought to the root meaning of these pronouns.

When speaking to a person of the same status or of younger age, ငါ nga [ŋà] ('I/me') and နင် nang [nɪ̃̀] ('you') may be used, although most speakers choose to use third person pronouns.[55] For example, an older person may use ဒေါ်လေး dau le: [dɔ̀ lé] ('aunt') or ဦးလေး u: lei: [ʔú lé] ('uncle') to refer to himself, while a younger person may use either သား sa: [t̪á] ('son') or သမီး sa.mi: [t̪əmí] ('daughter').

The basic pronouns are:

| Person | Singular | Plural* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informal | Formal | Informal | Formal | |

| First person | ငါ nga [ŋà] |

ကျွန်တော်‡ kywan to [tɕənɔ̀] ကျွန်မ† kywan ma. [tɕəma̰] |

ငါဒို့ nga tui. [ŋà do̰] |

ကျွန်တော်တို့‡ kywan to tui. [tɕənɔ̀ do̰] ကျွန်မတို့† kywan ma. tui. [tɕəma̰ do̰] |

| Second person | နင် nang [nɪ̃̀] မင်း mang: [mɪ̃́] |

ခင်ဗျား‡ khang bya: [kʰəmjá] ရှင်† hrang [ʃɪ̃̀] |

နင်ဒို့ nang tui. [nɪ̃̀n do̰] |

ခင်ဗျားတို့‡ khang bya: tui. [kʰəmjá do̰] ရှင်တို့† hrang tui. [ʃɪ̃̀n do̰] |

| Third person | သူ su [t̪ù] |

(အ)သင် (a.) sang [(ʔə)t̪ɪ̃̀] |

သူဒို့ su tui. [t̪ù do̰] |

သင်တို့ sang tui. [t̪ɪ̃̀ do̰] |

- * The basic particle to indicate plurality is တို့ tui., colloquial ဒို့ dui..

- ‡ Used by male speakers.

- † Used by female speakers.

Other pronouns are reserved for speaking with bhikkhus (Buddhist monks). When speaking to a bhikkhu, pronouns like ဘုန်းဘုန်း bhun: bhun: (from ဘုန်းကြီး phun: kri: 'monk'), ဆရာတော် chara dau [sʰəjàdɔ̀] ('royal teacher'), and အရှင်ဘုရား a.hrang bhu.ra: [ʔəʃɪ̃̀ pʰəjá] ('your lordship') are used depending on their status ဝါ. When referring to oneself, terms like တပည့်တော် ta. paey. tau ('royal disciple') or ဒကာ da. ka [dəɡà], ('donor') are used. When speaking to a monk, the following pronouns are used:

| Person | Singular | |

|---|---|---|

| Informal | Formal | |

| First person | တပည့်တော်† ta.paey. tau |

ဒကာ† da. ka [dəɡà] |

| Second person | ဘုန်းဘုန်း bhun: bhun: [pʰṍʊ̃ pʰṍʊ̃] (ဦး)ပဉ္စင်း (u:) pasang: [(ʔú) bəzín] |

အရှင်ဘုရား a.hrang bhu.ra: [ʔəʃɪ̃̀ pʰəjá] ဆရာတော်‡ chara dau [sʰəjàdɔ̀] |

- † The particle ma. မ is suffixed for women.

- ‡ Typically reserved for the chief monk of a kyaung (monastery_.

In colloquial Burmese, possessive pronouns are contracted when the root pronoun itself is low toned. This does not occur in literary Burmese, which uses ၏ [ḭ] as postpositional marker for possessive case instead of ရဲ့ [jɛ̰]. Examples include the following:

- ငါ [ŋà] "I" + ရဲ့ (postpositional marker for possessive case) = ငါ့ [ŋa̰] "my"

- နင် [nɪ̃̀] "you" + ရဲ့ (postpositional marker for possessive case) = နင့် [nɪ̰̃] "your"

- သူ [t̪ù] "he, she" + ရဲ့ (postpositional marker for possessive case) = သူ့ [t̪ṵ] "his, her"

The contraction also occurs in some low toned nouns, making them possessive nouns (e.g. အမေ့ or မြန်မာ့, "mother's" and "Myanmar's" respectively).

Kinship terms

Minor pronunciation differences do exist within regions of Irrawaddy valley. For example, the pronunciation [sʰʊ̃́] of ဆွမ်း "food offering [to a monk]" is preferred in Lower Burma, instead of [sʰwã́], which is preferred in Upper Burma. However, the most obvious difference between Upper Burmese and Lower Burmese is that Upper Burmese speech still differentiates maternal and paternal sides of a family:

| Term | Upper Burmese | Lower Burmese | Myeik dialect |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

1 The youngest (paternal or maternal) aunt may be called ထွေးလေး [dwé lé], and the youngest paternal uncle ဘထွေး [ba̰ dwé].

In a testament to the power of media, the Yangon-based speech is gaining currency even in Upper Burma. Upper Burmese-specific usage, while historically and technically accurate, is increasingly viewed as distinctly rural or regional speech. In fact, some usages are already considered strictly regional Upper Burmese speech and are likely to die out. For example:

| Term | Upper Burmese | Standard Burmese |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|

In general, the male-centric names of old Burmese for familial terms have been replaced in standard Burmese with formerly female-centric terms, which are now used by both sexes. One holdover is the use of ညီ ('younger brother to a male') and မောင် ('younger brother to a female'). Terms like နောင် ('elder brother to a male') and နှမ ('younger sister to a male') now are used in standard Burmese only as part of compound words like ညီနောင် ('brothers') or မောင်နှမ ('brother and sister').

Reduplication

Reduplication is prevalent in Burmese and is used to intensify or weaken adjectives' meanings. For example, if ချော [tɕʰɔ́] "beautiful" is reduplicated, then the intensity of the adjective's meaning increases. Many Burmese words, especially adjectives with two syllables, such as လှပ [l̥a̰pa̰] "beautiful", when reduplicated (လှပ → လှလှပပ [l̥a̰l̥a̰ pa̰pa̰]) become adverbs. This is also true of some Burmese verbs and nouns (e.g. ခဏ 'a moment' → ခဏခဏ 'frequently'), which become adverbs when reduplicated.

Some nouns are also reduplicated to indicate plurality. For instance, ပြည် [pjì] ('country'), but when reduplicated to အပြည်ပြည် [əpjì pjì], it means "many countries," as in အပြည်ပြည်ဆိုင်ရာ [əpjì pjì sʰã̀ɪ̃ jà] ('international'). Another example is အမျိုး, which means "a kind," but the reduplicated form အမျိုးမျိုး means "multiple kinds."

A few measure words can also be reduplicated to indicate "one or the other":

- ယောက် (measure word for people) → တစ်ယောက်ယောက် ('someone')

- ခု (measure word for things) → တစ်ခုခု ('something')

Romanization and transcription

There is no official romanization system for Burmese. There have been attempts to make one, but none have been successful. Replicating Burmese sounds in the Latin script is complicated. There is a Pali-based transcription system in existence, MLC Transcription System which was devised by the Myanmar Language Commission (MLC). However, it only transcribes sounds in formal Burmese and is based on the Burmese alphabet rather than the phonology.

Several colloquial transcription systems have been proposed, but none is overwhelmingly preferred over others.

Transcription of Burmese is not standardized, as seen in the varying English transcriptions of Burmese names. For instance, a Burmese personal name like ဝင်း [wɪ̃́] may be variously romanized as Win, Winn, Wyn, or Wynn, while ခိုင် [kʰã̀ɪ̃] may be romanized as Khaing, Khine, or Khain.

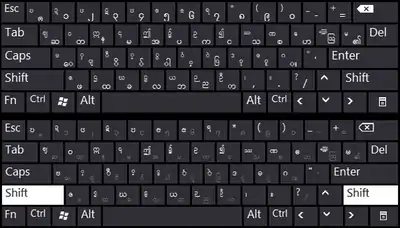

Computer fonts and standard keyboard layout

The Burmese script can be entered from a standard QWERTY keyboard and is supported within the Unicode standard, meaning it can be read and written from most modern computers and smartphones.

Burmese has complex character rendering requirements, where tone markings and vowel modifications are noted using diacritics. These can be placed before consonants (as with ေ), above them (as with ိ) or even around them (as with ြ). These character clusters are built using multiple keystrokes. In particular, the inconsistent placement of diacritics as a feature of the language presents a conflict between an intuitive WYSIWYG typing approach, and a logical consonant-first storage approach.

Since its introduction in 2007, the most popular Burmese font, Zawgyi, has been near-ubiquitous in Myanmar. Linguist Justin Watkins argues that the ubiquitous use of Zawgyi harms Myanmar languages, including Burmese, by preventing efficient sorting, searching, processing and analyzing Myanmar text through flexible diacritic ordering.[56]

Zawgyi is not Unicode-compliant, but occupies the same code space as Unicode Myanmar font.[57] As it is not defined as a standard character encoding, Zawgyi is not built in to any major operating systems as standard. However, allow for its position as the de facto (but largely undocumented) standard within the country, telcos and major smartphone distributors (such as Huawei and Samsung) ship phones with Zawgyi font overwriting standard Unicode-compliant fonts, which are installed on most internationally distributed hardware.[58] Facebook also supports Zawgyi as an additional language encoding for their app and website.[59] As a result, almost all SMS alerts (including those from telcos to their customers), social media posts and other web resources may be incomprehensible on these devices without the custom Zawgyi font installed at the operating system level. These may include devices purchased overseas, or distributed by companies who do not customize software for the local market.

Keyboards which have a Zawgyi keyboard layout printed on them are the most commonly available for purchase domestically.

Until recently, Unicode compliant fonts have been more difficult to type than Zawgyi, as they have a stricter, less forgiving and arguably less intuitive method for ordering diacritics. However, intelligent input software such as Keymagic[60] and recent versions of smartphone soft-keyboards including Gboard and ttKeyboard[61] allow for more forgiving input sequences and Zawgyi keyboard layouts which produce Unicode-compliant text.

A number of Unicode-compliant Burmese fonts exist. The national standard keyboard layout is known as the Myanmar3 layout, and it was published along with the Myanmar3 Unicode font. The layout, developed by the Myanmar Unicode and NLP Research Center, has a smart input system to cover the complex structures of Burmese and related scripts.

In addition to the development of computer fonts and standard keyboard layout, there is still a lot of scope of research for the Burmese language, specifically for Natural Language Processing (NLP) areas like WordNet, Search Engine, development of parallel corpus for Burmese language as well as development of a formally standardized and dense domain-specific corpus of Burmese language.[62]

Myanmar government has designated Oct 1 2019 as "U-Day" to officially switch to Unicode.[63] The full transition is estimated to take two years.[64]

Notes

- Mikael Parkvall, "Världens 100 största språk 2007" (The World's 100 Largest Languages in 2007), in Nationalencyklopedin

- Burmese at Ethnologue (15th ed., 2005)

- Constitution of the Republic of the Union of Myanmar (2008), Chapter XV, Provision 450

- Chang 2003.

- Sinley 1993, p. 147.

- Bradley 1993, p. 147.

- Barron et al. 2007, p. 16-17.

- Allott, Anna J. (1983). "Language policy and language planning in Burma". Pacific Linguistics. Series A. Occasional Papers. ProQuest 1297859465.

- Jenny, Mathias (2013). "The Mon language: Recipient and donor between Burmese and Thai". Journal of Language and Culture. 31 (2): 5–33. doi:10.5167/uzh-81044. ISSN 0125-6424.

- Burmese at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- Herbert, Patricia; Anthony Crothers Milner (1989). South-East Asia: Languages and Literatures: a Select Guide. University of Hawaii Press. p. 5. ISBN 9780824812676.

- Wheatley, Julian (2013). "12. Burmese". In Randy J. LaPolla; Graham Thurgood (eds.). Sino-Tibetan Languages. Routledge. ISBN 9781135797171.

- Aung-Thwin, Michael (2005). The Mists of Rāmañña: The Legend that was Lower Burma. University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2886-8.

- Lieberman, Victor (2018). "Was the Seventeenth Century a Watershed in Burmese History?". In Reid, Anthony J. S. (ed.). Southeast Asia in the Early Modern Era: Trade, Power, and Belief. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-3217-1.

- Lieberman 2003, p. 189.

- Lieberman 2003, p. 202-206.

- Herbert & Milner 1989.

- Adas, Michael (2011-04-20). The Burma Delta: Economic Development and Social Change on an Asian Rice Frontier, 1852–1941. Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 67–77. ISBN 9780299283537.

- Bradley 2010, p. 99.

- Bradley 1995, p. 140.

- Bradley, David (2019-10-02). "Language policy and language planning in mainland Southeast Asia: Myanmar and Lisu". Linguistics Vanguard. 5 (1). doi:10.1515/lingvan-2018-0071. S2CID 203848291.

- Bradley 1996, p. 746.

- Herbert & Milner 1989, p. 5–21.

- Aung Bala 1981, p. 81–99.

- Aung Zaw 2010, p. 2.

- San San Hnin Tun 2001, p. 39.

- Taw Sein Ko 1924, p. 68-70.

- San San Hnin Tun 2001, p. 48-49.

- San San Hnin Tun 2001, p. 26.

- Houtman 1990, p. 135-136.

- Wheatley 2013.

- Wheatley & Tun 1999, p. 64.

- UC 2012, p. 370.

- Wheatley & Tun 1999, p. 65.

- Wheatley & Tun 1999.

- Wheatley & Tun 1999, p. 81.

- Wheatley & Tun 1999, p. 67.

- Wheatley & Tun 1999, p. 94.

- Wheatley & Tun 1999, p. 68.

- MLC 1993.

- Chang (2003), p. 63.

- Watkins (2001).

- Jenny & San San Hnin Tun 2016, p. 15.

- Jones 1986, p. 135-136.

- Wheatley 1987.

- Taylor 1920, p. 91–106.

- Taylor 1920.

- Benedict 1948, p. 184–191.

- Khin Min 1987.

- Harvey 1925, p. 307.

- Aung-Thwin 2005, p. 167–178, 197–200.

- Lieberman 2003, p. 136.

- Taw Sein Ko 1924, p. viii.

- Bradley 1993, p. 157–160.

- Bradley 1993.

- Watkins, Justin. "Why we should stop Zawgyi in its tracks. It harms others and ourselves. Use Unicode!" (PDF).

- Myanmar Wikipedia – Font

- Hotchkiss, Griffin (23 March 2016). "Battle of the fonts".

- "Facebook nods to Zawgyi and Unicode".

- "Keymagic Unicode Keyboard Input Customizer".

- "TTKeyboard – Myanmar Keyboard".

- Saini 2016, p. 8.

- "Unicode in, Zawgyi out: Modernity finally catches up in Myanmar's digital world | The Japan Times". The Japan Times. Sep 27, 2019. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

Oct. 1 is “U-Day,” when Myanmar officially will adopt the new system. ... Microsoft and Apple helped other countries standardize years ago, but Western sanctions meant Myanmar lost out.

- Saw Yi Nanda (21 Nov 2019). "Myanmar switch to Unicode to take two years: app developer". The Myanmar Times. Retrieved 24 December 2019.

References

- Julie D. Allen; et al., eds. (April 2012). "11. Southeast Asian Scripts" (PDF). The Unicode Standard Version 6.1 – Core Specification. Mountain View, CA: The Unicode Consortium. pp. 368–373. ISBN 978-1-936213-02-3.

- Aung-Thwin, Michael (2005). The Mists of Rāmañña: The Legend that was Lower Burma (illustrated ed.). Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2886-8.

- Aung Bala (1981). "Contemporary Burmese literature". Contributions to Asian Studies. 16.

- Aung Zaw (September 2010). "Tell the World the Truth". The Irrawaddy. 18 (9). Archived from the original on 2010-09-18.

- Barron, Sandy; Okell, John; Yin, Saw Myat; VanBik, Kenneth; Swain, Arthur; Larkin, Emma; Allott, Anna J.; Ewers, Kirsten (2007). Refugees from Burma: Their Backgrounds and Refugee Experiences (PDF) (Report). Center for Applied Linguistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-04-27. Retrieved 2010-08-20.

- Benedict, Paul K. (Oct–Dec 1948). "Tonal Systems in Southeast Asia". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 68 (4): 184–191. doi:10.2307/595942. JSTOR 595942.

- Bradley, David (Spring 1993). "Pronouns in Burmese–Lolo" (PDF). Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area. 16 (1).

- Bradley, David (2006). Ulrich Ammon; Norbert Dittmar; Klaus J. Mattheier; Peter Trudgill (eds.). Sociolinguistics / Soziolinguistik. 3. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-018418-1.

- Bradley, David (1996). Atlas of Languages of Intercultural Communication in the Pacific, Asia, and the Americas. 1. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-013417-9.

- Bradley, David (1989). "Uncles and Aunts: Burmese Kinship and Gender" (PDF). South-east Asian Linguisitics: Essays in Honour of Eugénie J.A. Henderson: 147–162. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-10-11. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- Bradley, David (2010). "9. Burma, Thailand, Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam" (PDF). In Martin J. Ball (ed.). The Routledge Handbook of Sociolinguistics Around the World. Routledge. pp. 98–99. ISBN 978-0-415-42278-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-07-16.

- Bradley, David (1995). "Reflexives in Burmese" (PDF). Papers in Southeast Asian Linguistics No. 13: Studies in Burmese Languages (A-83): 139–172.

- Bradley, David (May 2011). "Changes in Burmese Phonology and Orthography". SEALS Conference. Kasetsart University. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- Bradley, David (2012). "The Characteristics of the Burmic Family of Tibeto-Burman". Language and Linguistics. 13 (1): 171–192.

- Chang, Charles Bond (2003). "High-Interest Loans": The Phonology of English Loanword Adaptation in Burmese (B.A. thesis). Harvard University. Retrieved 2011-05-24.

- Chang, Charles B. (2009). "English loanword adaptation in Burmese" (PDF). Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society. 1: 77–94.

- Harvey, G. E. (1925). History of Burma: From the Earliest Times to 10 March 1824. London: Frank Cass & Co. Ltd.

- Herbert, Patricia M.; Milner, Anthony (1989). South-East Asia Languages and Literatures: A Select Guide. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1267-6.

- Hill, Nathan W. (2012). "Evolution of the Burmese Vowel System" (PDF). Transactions of the Philological Society. 110 (1): 64–79. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.694.9405. doi:10.1111/j.1467-968x.2011.01282.x.

- San San Hnin Tun (2001). Burmese Phrasebook. Vicky Bowman. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74059-048-8.

- Houtman, Gustaaf (1990). Traditions of Buddhist Practice in Burma. Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa.

- Jones, Robert (1986). McCoy, John; Light, Timothy (eds.). Pitch register languages. Contributions to Sino-Tibetan Studies. E. J. Brill.

- Khin Min, Maung (1987). "Old Usage Styles of Myanmar Script". Myanmar Unicode & NLP Research Center. Archived from the original on 2006-09-23. Retrieved 2008-07-29.

- Lieberman, Victor B. (2003). Strange Parallels: Southeast Asia in Global Context, c. 800–1830, volume 1, Integration on the Mainland. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80496-7.

- Myanmar–English Dictionary. Myanmar Language Commission. 1993. ISBN 978-1-881265-47-4.

- Nishi, Yoshio (30 October 1998). "The Development of Voicing Rules in Standard Burmese" (PDF). Bulletin of the National Museum of Ethnology. 23 (1): 253–260.

- Nishi, Yoshio (31 March 1998). "The Orthographic Standardization of Burmese: Linguistic and Sociolinguistic Speculations" (PDF). Bulletin of the National Museum of Ethnology. 22: 975–999. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2013.

- Okell, John (2002). Burmese By Ear or Essential Myanmar (PDF). London: The School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. ISBN 978-1-86013-758-7.

- Saini, Jatinderkumar R. (30 June 2016). "First Classified Annotated Bibliography of NLP Tasks in the Burmese Language of Myanmar". Revista InforComp (INFOCOMP Journal of Computer Science). 15 (1): 1–11.

- San San Hnin Tun (2006). Discourse Marking in Burmese and English: A Corpus-Based Approach (PDF) (Thesis). University of Nottingham. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-21. Retrieved 2013-10-20.

- Taw Sein Ko (1924). Elementary Handbook of the Burmese Language. Rangoon: American Baptist Mission Press.

- Taylor, L. F. (1920). "On the tones of certain languages of Burma". Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies. 1 (4): 91–106. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00101685. JSTOR 607065.

- Wheatley, Julian; Tun, San San Hnin (1999). "Languages in contact: The case of English and Burmese". The Journal of Burma Studies. 4.

- Wheatley, Julian (2013). "12. Burmese". In Randy J. LaPolla; Graham Thurgood (eds.). Sino-Tibetan Languages. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-79717-1.

- Wheatley, Julian K. (1987). "Burmese". In B. Comrie (ed.). Handbook of the world's major languages. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 834–54. ISBN 978-0-19-520521-3.

- Yanson, Rudolf A. (2012). Nathan Hill (ed.). Aspiration in the Burmese Phonological System: A Diachronic Account. Medieval Tibeto-Burman Languages IV. BRILL. pp. 17–29. ISBN 978-90-04-23202-0.

- Yanson, Rudolf (1994). Uta Gärtner; Jens Lorenz (eds.). Chapter 3. Language. Tradition and Modernity in Myanmar. LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 366–426. ISBN 978-3-8258-2186-9.

- Jenny, Mathias; San San Hnin Tun (2016). Burmese: A Comprehensive Grammar. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 9781317309314.

Bibliography

- Becker, Alton L. (1984). "Biography of a sentence: A Burmese proverb". In E. M. Bruner (ed.). Text, play, and story: The construction and reconstruction of self and society. Washington, D.C.: American Ethnological Society. pp. 135–55.

- Bernot, Denise (1980). Le prédicat en birman parlé (in French). Paris: SELAF. ISBN 978-2-85297-072-4.

- Chang, Charles Bond (2003). "High-Interest Loans": The Phonology of English Loanword Adaptation in Burmese (B.A. thesis). Harvard University. Retrieved 2011-05-24.

- Cornyn, William Stewart (1944). Outline of Burmese grammar. Baltimore: Linguistic Society of America.

- Cornyn, William Stewart; D. Haigh Roop (1968). Beginning Burmese. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Cooper, Lisa; Beau Cooper; Sigrid Lew (2012). "A phonetic description of Burmese obstruents". 45th International Conference on Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics. Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

- Green, Antony D. (2005). "Word, foot, and syllable structure in Burmese". In J. Watkins (ed.). Studies in Burmese linguistics. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics. pp. 1–25. ISBN 978-0-85883-559-7.

- Okell, John (1969). A reference grammar of colloquial Burmese. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-7007-1136-9.

- Roop, D. Haigh (1972). An introduction to the Burmese writing system. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-01528-7.

- Taw Sein Ko (1924). Elementary handbook of the Burmese language. Rangoon: American Baptist Mission Press.

- Watkins, Justin W. (2001). "Illustrations of the IPA: Burmese" (PDF). Journal of the International Phonetic Association. 31 (2): 291–295. doi:10.1017/S0025100301002122.

- Patricia M Herbert, Anthony Milner, ed. (1989). South East Asia Languages and Literatures: Languages and Literatures: A Select Guide. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1267-6.

- Waxman, Nathan; Aung, Soe Tun (2014). "The Naturalization of Indic Loan-Words into Burmese: Adoption and Lexical Transformation". Journal of Burma Studies. 18 (2): 259–290. doi:10.1353/jbs.2014.0016. S2CID 110774660.

External links

| Burmese edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| For a list of words relating to Burmese language, see the Burmese language category of words in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Burmese phrasebook travel guide from Wikivoyage

Burmese phrasebook travel guide from Wikivoyage- Omniglot: Burmese Language

- Learn Burmese online

- Online Burmese lessons

- Burmese language resources from SOAS

- "E-books for children with narration in Burmese". Unite for Literacy library. Retrieved 2014-06-21.

- Myanmar Unicode and NLP Research Center

- Myanmar 3 font and keyboard

- Burmese online dictionary (Unicode)

- Ayar Myanmar online dictionary

- Myanmar unicode character table

- Download KaNaungConverter_Window_Build200508.zip from the Kanaung project page and Unzip Ka Naung Converter Engine