Qilin

The qilin ([tɕʰǐ.lǐn]; Chinese: 麒麟), or kirin in Japanese, is a mythical hooved chimerical creature known in Chinese and other East Asian cultures, said to appear with the imminent arrival or passing of a sage or illustrious ruler.[1] Qilin is a specific type of the lin mythological family of one-horned beasts.

| Qilin | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.svg.png.webp) "Qilin" in Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 麒麟 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | kỳ lân | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 麒麟 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 기린 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 麒麟 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 麒麟 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | きりん | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

Origins

The earliest references to the qilin are in the 5th century BC Zuo Zhuan.[2][3] The qilin made appearances in a variety of subsequent Chinese works of history and fiction, such as Feng Shen Bang. Emperor Wu of Han apparently captured a live qilin in 122 BC, although Sima Qian was skeptical of this.[4]

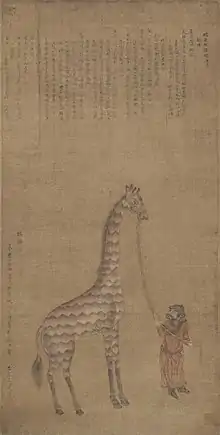

The legendary image of the qilin became associated with the image of the giraffe in the Ming dynasty.[5][6] The identification of the qilin with giraffes began after Zheng He's 15th-century voyage to East Africa (landing, among other places, in modern-day Somalia). The Ming Dynasty bought giraffes from the Somali merchants along with zebras, incense, and various other exotic animals.[7] Zheng He's fleet brought back two giraffes to Nanjing, and they were referred to as "qilins".[8] The Emperor proclaimed the giraffes magical creatures, whose capture signaled the greatness of his power.

It is said that the female is called the lin (麟), the male is called the qi (麒) and "qilin" is a designation for the whole species. However, "lin" alone often carries the same generic meaning.[9]

The identification between the qilin and the giraffe is supported by some attributes of the qilin, including its herbivory and quiet nature. Its reputed ability to "walk on grass without disturbing it" may be related to the giraffe's long, thin legs. Also the qilin is described as having antlers like a deer and scales like a dragon or fish; since the giraffe has horn-like "ossicones" on its head and a tessellated coat pattern that looks like scales, it is easy to draw an analogy between the two creatures. The identification of qilin with giraffes has had lasting influence: even today, the same word is used for the mythical animal and the giraffe in both Korean and Japanese.[10]

Axel Schuessler reconstructs 麒麟's Old Chinese pronunciation as *gərin. Finnish linguist Juha Janhunen tentatively compares *gərin to an etymon reconstructed as *kalimV,[11] denoting "whale"; and represented in the language isolate Nivkh and four different language families Tungusic, Mongolic, Turkic and Samoyedic, wherein *kalay(ә)ng means "whale" (in Nenets) and *kalVyǝ "mammoth" (in Enets and Nganasan). As even aborigines "vaguely familiar with the underlying real animals" often confuse the whale, mammoth, and unicorn: they conceptualized the mammoth and whale as aquatic, as well as the mammoth and unicorn possessing a single horn; for inland populations, the extant whale "remains [...] an abstraction, in this respect being no different from the extinct mammoth or the truly mythical unicorn." However, Janhunen cautiously remarks that "[t]he formal and semantic similarity between *kilin < *gilin ~ *gïlin 'unicorn' and *kalimV 'whale' (but also Samoyedic *kalay- 'mammoth') is sufficient to support, though perhaps not confirm, the hypothesis of an etymological connection", and also notes a possible connection between Old Chinese and Mongolian (*)kers ~ (*)keris ~ (*)kiris "rhinoceros" (Khalkha: хирс).[12] Arceus resembles one.

Description

The qilin may be described or depicted in a variety of ways.

Qilin generally have Chinese dragon-like features. Most notably their heads, eyes with thick eyelashes, manes that always flow upward and beards. The body is fully or partially scaled and often shaped like an ox, deer, or horse. They are always shown with cloven hooves. In modern times, the depictions of qilin have often fused with the Western concept of unicorns.

As the Chinese dragon has antlers, it is most common to see qilin with antlers. Dragons in China are also most commonly depicted as golden, therefore the most common depictions of qilin are also golden, but may be any color, multicolored, or with various colors of fur or hide.

The qilin are depicted throughout a wide range of Chinese art, sometimes with parts of their bodies on fire. On occasion, they will have feathery features or decorations, fluffy curly tufts of hair, as depicted in Ming Dynasty horse art on various parts of the legs, from fetlocks to upper legs, or even with decorative fish-like fins as embellishments, or carp fish whiskers, or scales.

Qilin are often depicted as somewhat bejeweled, or as brilliant as jewels themselves, like Chinese dragons. They are often associated in colors with the elements, precious metals, stars, and gem stones. But, qilin can also be earthy and modest browns or earth-tones. It is said their auspicious voice sounds like the tinkling of bells, chimes, and the wind.

According to Taoist mythology, although they can look fearsome, qilin only punish the wicked; thus there exist accounts of court trials and judgements based on qilin divinely knowing whether a defendant is good or evil, guilty or innocent, in ancient lore and stories.

In Buddhist-influenced depictions, qilin will refuse to walk upon grass for fear of harming a single blade, and thus are often depicted walking upon the clouds or the water. As they are divine and peaceful creatures, their diets do not include flesh. They take great care when they walk to never tread on a living creature, and appear only in areas ruled by a wise and benevolent leader, which can include a household. Qilin can become fierce if a pure person is threatened by a malicious one, spouting flames from their mouths and exercising other fearsome powers that vary from story to story.

Legends tell that qilin have appeared in the garden of the legendary Yellow Emperor and in the capital of Emperor Yao. Both events bore testimony to the benevolent nature of the rulers. It has been told in legends that the birth of the great sage Confucius was foretold by the arrival of a qilin.[1]

Qilin are thought to be a symbol of luck, good omens, protection, prosperity, success and longevity by the Chinese. Qilin are also a symbol of fertility, and often depicted as bringing a baby to a family.

In ritual dances

Some stories state that qilin are sacred pets (or familiars) of the deities. Therefore, in the hierarchy of traditional dances performed by the Chinese (e.g., lion dance, dragon dance), they rank highly; third only to the dragon and phoenix who are the highest.

In the qilin dance, movements are characterized by fast, powerful strokes of the head. The Qilin Dance is often regarded as a hard dance to perform due to the weight of the head, the stances involved, and the emphasis on sudden bursts of energy (法劲; 法勁; fǎjìn).

Qilin as unicorns

.jpg.webp)

Qilin (麒麟) is often translated into English as "unicorn", as it can sometimes be depicted as having a single horn, although this is misleading, as qilin may also be depicted as having two horns. A separate word, "one-horned beast" (独角兽; 獨角獸; Dújiǎoshòu) is used in modern Chinese for "unicorns". A number of different Chinese mythical creatures can be depicted with a single horn, and a qilin, even if depicted with one horn, would be called a "one-horned qilin" in Chinese, not a "unicorn". Due to the mythical, mystical, and even whimsical similarities to the Western unicorn, however, the Chinese government has minted silver, gold, and platinum commemorative coins which depict both archetypal creatures.[13]

Variations

There are variations in the appearance of the qilin, even in historical China, owing to cultural differences between dynasties and regions.

Jin

During the Jin dynasty, the qilin was depicted as wreathed in flame and smoke, with a dragon-like head, scales, and the body of a powerful hooved beast such as a horse.

Ming

In the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), the qilin was represented as an oxen-hoofed animal with a dragon-like head surmounted by a pair of horns and flame-like head ornaments.

Qing

The qilin of China's subsequent Manchu Qing dynasty (1644–1911) was a particular fanciful animal with the head of a dragon, the antlers of a deer, the skin and scales of a fish, the hooves of an ox and tail of a lion.

Korea

Girin, Kirin, or 기린 is the Korean form of "qilin". It is described as a maned creature with the torso of a deer, an ox tail with the hooves of a horse. The qilin in Korean art were initially depicted as more deer-like, however over time they have transformed into more horse-like.[14] They were one of the four divine creatures along with the dragon, phoenix and turtle. Qilin were extensively used in Korean royal and Buddhist arts.

In modern Korean, the term "girin" is used for "giraffe".

Japan

Kirin is the Japanese form of "qilin", which has also come to be used in the modern Japanese word for a giraffe. Japanese art tends to depict the kirin as more deer-like than in Chinese art. Alternatively, it is depicted as a dragon shaped like a deer, but with an ox's tail[15] instead of a lion's tail. They are also often portrayed as partially unicorn-like in appearance, but with a backwards curving horn.

In the Post-Qin Chinese hierarchy of mythological animals, the qilin is ranked as the third most powerful creature (after the dragon and phoenix), but in Japan, the kirin occupies the top spot. This is following the style of the ancient Chinese, as qilin was ranked higher than the dragon or phoenix before the Qin dynasty. During the Zhou dynasty, the qilin was ranked the highest, the phoenix ranked second, and the dragon the third.

Thailand

In Thailand, the Qílín is known as 'Gilen' (Thai; กิเลน), and is a member of the pantheon of Thai Himapant forest mythical animals. It is most probable that the Gilen was introduced into the pantheon under the influence of the Tai Yai who came down from Southern China to settle in Siam in ancient times, and the legend was probably incorporated into the Himapant legends of Siam in this manner. The Gilen is a mixture of various animals, which come from differing elemental environments, representing elemental magical forces present within each personified creature. Many of the Himapant animals actually represent gods and devas of the Celestial Realms, and bodhisattvas, who manifest as personifications which represent the true nature of each creature deity through the symbolism of the various body parts amalgamated into the design of the Mythical creature.[16]

Vietnam

In Vietnam, the Qilin is referred to as Kỳ lân. The origins of the Kỳ lân is descended from the Chinese Qilin, and shares many similar features, such as the head of a dragon or tiger, mane of a lion, the hooves of an ox or horse, the tail of a lion or ox, scales of a fish, and it can have either 1 or 2 horns or antlers.

Cultural representations

.jpg.webp)

The qilin has been frequently depicted in works of literature and art:

- In Jorge Luis Borges's Book of Imaginary Beings, there is a section on "The Unicorn of China".

- In Takashi Miike's The Great Yokai War, the hero is bitten during a street festival by the dancer's kirin head. According to local custom that makes him the next "kirin rider", a hero who defeats malevolent yokai; he is seen riding the kirin through the skies at the climax of the film.

- In The Twelve Kingdoms anime series, based on the fantasy novels by Fuyumi Ono, the monarch of each kingdom is chosen by a kirin, who then becomes his or her principal counselor.[17]

- In the Dungeons & Dragons universe, the Ki-rin are monsters in the Oriental Adventures setting, cited as an example of how D&D uses influences from many places.[18][19]

- In the video game series Final Fantasy, Kirin is one of the Espers (summoned monsters) in Final Fantasy VI and Final Fantasy Tactics Advance. Kirin also makes an appearance as the strongest of the "gods" in Final Fantasy XI, and is a mount available in Final Fantasy XIV.[20]

- In Gosei Sentai Dairanger, Kazu of the Heavenly Time Star uses his Chi to manifest the power of the kirin to become the KirinRanger (キリンレンジャー, Kirin Renjā) and pilots the Mythical Chi Beast Star-Kirin (気伝獣星麒麟, Kidenjū Sei-Kirin).[21]

- At the beginning of 47 Ronin, a Kirin is sent to kill Lord Asano in the forest of Akō, where it is then hunted by his samurai.

- In the video game series Monster Hunter, the Kirin are classified as one of the Elder Dragons. Resembling a unicorn covered in scales, they are extremely agile and can summon lightning at will.

- The Kirin Brewery Company, Limited (麒麟麦酒株式会社) is a Japanese brewery company which has a Kirin prominently featured on its logo.[22]

- In My Little Pony: Friendship Is Magic, kirin are introduced in the season eight episode "Sounds of Silence". They are here depicted as a type of pony. When angered they transform into fiery destructive creatures known as nirik (their name spelled backwards).[23]

See also

References

- "qilin (Chinese mythology)". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 24 July 2011.

- Chinese Literature – Chunqiu-Zuozhuan 春秋左傳, Gongyangzhuan 公羊傳, Guliangzhuan 穀梁傳 (www.chinaknowledge.de)

- 古建上的主要装饰纹样――麒麟 古建园林技术-作者:徐华铛 Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- zh:s:史記/卷028

- 此“麟”非彼“麟”专家称萨摩麟并非传说中麒麟

- 傳說中的聖獸--麒麟

- Wilson, Samuel M. "The Emperor's Giraffe", Natural History Vol. 101, No. 12, December 1992 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 2, 2008. Retrieved April 14, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- 傳世麒麟圖考察初稿 張之傑

- ChinaKnowledge.de

- Parker, J. T.:" The Mythic Chinese Unicorn"

- Janhunen, J. (2011). Unicorn, Mammoth, Whale: mythological and etymological connections of zoonyms in North and East Asia. Linguistics, Archaeology and the Human Past, Occasional Paper, 12, 189–222.

- Хирс in Bolor dictionary

- "5 Yuan, China". en.numista.com. Numista. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- 기린 : 네이버캐스트

- Griffis, William Elliot (October 2007). The Religions of Japan. Bibliobazaar. p. 39. ISBN 978-1-4264-9918-0.

- "Taep Payatorn Riding Qilin Himapant Lion Hlang Yant – Nuea Pong Maha Sanaeh Luan – Ajarn Warut – Wat Pong Wonaram". Buddha Magic Multimedia & Publications. Retrieved January 12, 2016.

- Twelve Kingdoms Kirin

- Rubin, Jonathan (March 6, 2008). "Farewell to the Dungeon Master: How D&D creator Gary Gygax changed geekdom forever."" Slate.com. Accessed February 2012.

- AD&D Monster Manual

- FFVI Espers Kirin

- "Gosei Sentai Dairanger". Toei Entertainment. Retrieved November 24, 2015.

- "The Kirin: a mythological beast that portends happiness". Kirin Brewing company. Archived from the original on June 15, 2012. Retrieved September 28, 2012.

- Sounds of Silence, retrieved 2019-11-19

External links

Media related to Qilin at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Qilin at Wikimedia Commons