Wuxing (Chinese philosophy)

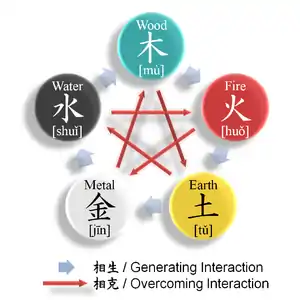

Wuxing (Chinese: 五行; pinyin: wǔxíng), usually translated as Five Phases, is a fivefold conceptual scheme that many traditional Chinese fields used to explain a wide array of phenomena, from cosmic cycles to the interaction between internal organs, and from the succession of political regimes to the properties of medicinal drugs. The "Five Phases" are Fire (火 huǒ), Water (水 shuǐ), Wood (木 mù), Metal or Gold (金 jīn), and Earth or Soil (土 tǔ). This order of presentation is known as the "Days of the Week" sequence. In the order of "mutual generation" (相生 xiāngshēng), they are Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, and Water. In the order of "mutual overcoming" (相剋/相克 xiāngkè), they are Wood, Earth, Water, Fire, and Metal.[1][2][3]

| Wuxing | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese | 五行 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Part of a series on |

| Taoism |

|---|

|

| Classical elements |

|---|

|

Stoicheion (στοιχεῖον) |

|

Wuxing (五行) |

|

Godai (五大) |

|

Bön |

|

Alchemy |

The system of five phases was used for describing interactions and relationships between phenomena. After it came to maturity in the second or first century BCE during the Han dynasty, this device was employed in many fields of early Chinese thought, including seemingly disparate fields such as Yi jing divination, alchemy, feng shui, astrology, traditional Chinese medicine, music, military strategy, and martial arts.

Names

Xíng (行) of wǔxíng (五行) means moving; a planet is called a 'moving star' (行星 xíngxīng) in Chinese. Wǔxíng originally refers to the five major planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Mercury, Mars, Venus) that create five dimensions of earth life.[4] Wǔxíng is also widely translated as "Five Elements" and this is used extensively by many including practitioners of Five Element acupuncture. This translation arose by false analogy with the Western system of the four elements.[5] Whereas the classical Greek elements were concerned with substances or natural qualities, the Chinese xíng are "primarily concerned with process and change," hence the common translation as "phases" or "agents".[6] By the same token, Mù is thought of as "Tree" rather than "Wood".[7] The word element is thus used within the context of Chinese medicine with a different meaning to its usual meaning.

It should be recognized that the word phase, although commonly preferred, is not perfect. Phase is a better translation for the five seasons (五運 wǔyùn) mentioned below, and so agents or processes might be preferred for the primary term xíng. Manfred Porkert attempts to resolve this by using Evolutive Phase for 五行 wǔxíng and Circuit Phase for 五運 wǔyùn, but these terms are unwieldy.

Some of the Mawangdui Silk Texts (no later than 168 BC) also present the wǔxíng as "five virtues" or types of activities.[8] Within Chinese medicine texts the wǔxíng are also referred to as wǔyǔn (五運) or a combination of the two characters (五行運 wǔxíngyǔn) these emphasise the correspondence of five elements to five 'seasons' (four seasons plus one). Another tradition refers to the wǔxíng as wǔdé (五德), the Five Virtues.

The phases

The five phases are around 73 days each and are usually used to describe the state in nature:

- Wood/Spring: a period of growth, which generates abundant wood and vitality

- Fire/Summer: a period of swelling, flowering, brimming with fire and energy

- Earth: the in-between transitional seasonal periods, or a separate 'season' known as Late Summer or Long Summer – in the latter case associated with leveling and dampening (moderation) and fruition

- Metal/Autumn: a period of harvesting and collecting

- Water/Winter: a period of retreat, where stillness and storage pervades

Cycles

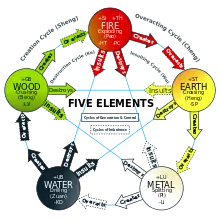

The doctrine of five phases describes two cycles, a generating or creation (生 shēng) cycle, also known as "mother-son", and an overcoming or destruction (剋/克 kè) cycle, also known as "grandfather-grandson", of interactions between the phases. Within Chinese medicine the effects of these two main relations are further elaborated:

- Inter-promoting (相生 xiāngshēng): the effect in the generating (生 shēng) cycle

- Weakening (相洩/相泄 xiāngxiè): the effect in a deficient or reverse generating (生 shēng) cycle

- Inter-regulating (相剋/相克 xiāngkè): the effect in the overcoming (剋/克 kè) cycle

- Overacting (相乘 xiāngchéng): the effect in an excessive overcoming (剋/克 kè) cycle

- Counteracting (相侮 xiāngwǔ or 相耗 xiānghào??): the effect in a deficient or reverse overcoming (剋/克 kè) cycle

Inter-promoting

Common verbs for the shēng cycle include "generate", "create" or "strengthens", as well as "grow" or "promote". The phase interactions in the shēng cycle are:

- Wood feeds Fire

- Fire produces Earth (ash, lava)

- Earth bears Metal (geological processes produce minerals)

- Metal collects Water (water vapor condenses on metal)

- Water nourishes Wood

Weakening

A deficient shēng cycle is called the xiè cycle and is the reverse of the shēng cycle. Common verbs for the xiè include "weaken", "drain", "diminish" or "exhaust". The phase interactions in the xiè cycle are:

- Wood depletes Water

- Water rusts Metal

- Metal impoverishes Earth (overmining or over-extraction of the earth's minerals)

- Earth smothers Fire

- Fire burns Wood (forest fires)

Inter-regulating

Common verbs for the kè cycle include "controls", "restrains" and "fathers", as well as "overcome" or "regulate". The phase interactions in the kè cycle are:

- Wood parts (or stabilizes) Earth (roots of trees can prevent soil erosion)

- Earth contains (or directs) Water (dams or river banks)

- Water dampens (or regulates) Fire

- Fire melts (or refines or shapes) Metal

- Metal chops (or carves) Wood

Overacting

An excessive kè cycle is called the chéng cycle. Common verbs for the chéng cycle include "restrict", "overwhelm", "dominate" or "destroy". The phase interactions in the chéng cycle are:

- Wood depletes Earth (depletion of nutrients in soil, overfarming, overcultivation)

- Earth obstructs Water (over-damming)

- Water extinguishes Fire

- Fire vaporizes Metal

- Metal overharvests Wood (deforestation)

Counteracting

A deficient kè cycle is called the wǔ cycle and is the reverse of the kè cycle. Common verbs for the wǔ cycle can include "insult" or "harm". The phase interactions in the wǔ cycle are:

- Wood dulls Metal

- Metal de-energizes Fire (metals conduct heat away)

- Fire evaporates Water

- Water muddies (or destabilizes) Earth

- Earth rots Wood (overpiling soil on wood can rot the wood)

Cosmology and feng shui

According to wuxing theory, the structure of the cosmos mirrors the five phases. Each phase has a complex series of associations with different aspects of nature, as can be seen in the following table. In the ancient Chinese form of geomancy, known as Feng Shui, practitioners all based their art and system on the five phases (wuxing). All of these phases are represented within the trigrams. Associated with these phases are colors, seasons and shapes; all of which are interacting with each other.[9]

Based on a particular directional energy flow from one phase to the next, the interaction can be expansive, destructive, or exhaustive. A proper knowledge of each aspect of energy flow will enable the Feng Shui practitioner to apply certain cures or rearrangement of energy in a way they believe to be beneficial for the receiver of the Feng Shui Treatment.

| Movement | Metal | Metal | Fire | Wood | Wood | Water | Earth | Earth |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trigram hanzi | 乾 | 兌 | 離 | 震 | 巽 | 坎 | 艮 | 坤 |

| Trigram pinyin | qián | duì | lí | zhèn | xùn | kǎn | gèn | kūn |

| Trigrams | ☰ | ☱ | ☲ | ☳ | ☴ | ☵ | ☶ | ☷ |

| I Ching | Heaven | Lake | Fire | Thunder | Wind | Water | Mountain | Field |

| Planet (Celestial Body) | Neptune | Venus | Mars | Jupiter | Pluto | Mercury | Uranus | Saturn |

| Color | Indigo | White | Crimson | Green | Scarlet | Black | Purple | Yellow |

| Day | Friday | Friday | Tuesday | Thursday | Thursday | Wednesday | Saturday | Saturday |

| Season | Autumn | Autumn | Summer | Spring | Spring | Winter | Intermediate | Intermediate |

| Cardinal direction | West | West | South | East | East | North | Center | Center |

Dynastic transitions

According to the Warring States period political philosopher Zou Yan 鄒衍 (c. 305–240 BCE), each of the five elements possesses a personified "virtue" (de 德), which indicates the foreordained destiny (yun 運) of a dynasty; accordingly, the cyclic succession of the elements also indicates dynastic transitions. Zou Yan claims that the Mandate of Heaven sanctions the legitimacy of a dynasty by sending self-manifesting auspicious signs in the ritual color (yellow, blue, white, red, and black) that matches the element of the new dynasty (Earth, Wood, Metal, Fire, and Water). From the Qin dynasty onward, most Chinese dynasties invoked the theory of the Five Elements to legitimize their reign.[10]

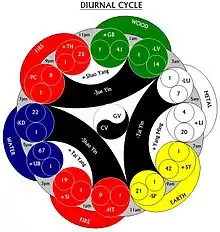

Chinese medicine

The interdependence of zang-fu networks in the body was said to be a circle of five things, and so mapped by the Chinese doctors onto the five phases.[11][12]

In order to explain the integrity and complexity of the human body, Chinese medical scientists and physicians use the Five Elements theory to classify the human body's endogenous influences on organs, physiological activities, pathological reactions, and environmental or exogenous influences.This diagnostic capacity is extensively used in traditional five phase acupunture today, as opposed to the modern eight principal based Traditional Chinese medicine.[13][14]

Celestial stem

| Movement | Wood | Fire | Earth | Metal | Water |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heavenly Stem | Jia 甲 Yi 乙 | Bing 丙 Ding 丁 | Wu 戊 Ji 己 | Geng 庚 Xin 辛 | Ren 壬 Gui 癸 |

| Year ends with | 4, 5 | 6, 7 | 8, 9 | 0, 1 | 2, 3 |

Ming neiyin

In Ziwei, neiyin (纳音) or the method of divination is the further classification of the Five Elements into 60 ming (命), or life orders, based on the ganzhi. Similar to the astrology zodiac, the ming is used by fortune-tellers to analyse a person's personality and future fate.

| Order | Ganzhi | Ming | Order | Ganzhi | Ming | Element |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Jia Zi 甲子 | Sea metal 海中金 | 31 | Jia Wu 甲午 | Sand metal 沙中金 | Metal |

| 2 | Yi Chou 乙丑 | 32 | Yi Wei 乙未 | |||

| 3 | Bing Yin 丙寅 | Furnace fire 炉中火 | 33 | Bing Shen 丙申 | Forest fire 山下火 | Fire |

| 4 | Ding Mao 丁卯 | 34 | Ding You 丁酉 | |||

| 5 | Wu Chen 戊辰 | Forest wood 大林木 | 35 | Wu Xu 戊戌 | Meadow wood 平地木 | Wood |

| 6 | Ji Si 己巳 | 36 | Ji Hai 己亥 | |||

| 7 | Geng Wu 庚午 | Road earth 路旁土 | 37 | Geng Zi 庚子 | Adobe earth 壁上土 | Earth |

| 8 | Xin Wei 辛未 | 38 | Xin Chou 辛丑 | |||

| 9 | Ren Shen 壬申 | Sword metal 剑锋金 | 39 | Ren Yin 壬寅 | Precious metal 金白金 | Metal |

| 10 | Gui You 癸酉 | 40 | Gui Mao 癸卯 | |||

| 11 | Jia Xu 甲戌 | Volcanic fire 山头火 | 41 | Jia Chen 甲辰 | Lamp fire 佛灯火 | Fire |

| 12 | Yi Hai 乙亥 | 42 | Yi Si 乙巳 | |||

| 13 | Bing Zi 丙子 | Cave water 洞下水 | 43 | Bing Wu 丙午 | Sky water 天河水 | Water |

| 14 | Ding Chou 丁丑 | 44 | Ding Wei 丁未 | |||

| 15 | Wu Yin 戊寅 | Fortress earth 城头土 | 45 | Wu Shen 戊申 | Highway earth 大驿土 | Earth |

| 16 | Ji Mao 己卯 | 46 | Ji You 己酉 | |||

| 17 | Geng Chen 庚辰 | Wax metal 白腊金 | 47 | Geng Xu 庚戌 | Jewellery metal 钗钏金 | Metal |

| 18 | Xin Si 辛巳 | 48 | Xin Hai 辛亥 | |||

| 19 | Ren Wu 壬午 | Willow wood 杨柳木 | 49 | Ren Zi 壬子 | Mulberry wood 桑柘木 | Wood |

| 20 | Gui Wei 癸未 | 50 | Gui Chou 癸丑 | |||

| 21 | Jia Shen 甲申 | Stream water 泉中水 | 51 | Jia Yin 甲寅 | Rapids water 大溪水 | Water |

| 22 | Yi You 乙酉 | 52 | Yi Mao 乙卯 | |||

| 23 | Bing Xu 丙戌 | Roof tiles earth 屋上土 | 53 | Bing Chen 丙辰 | Desert earth 沙中土 | Earth |

| 24 | Ding Hai 丁亥 | 54 | Ding Si 丁巳 | |||

| 25 | Wu Zi 戊子 | Lightning fire 霹雳火 | 55 | Wu Wu 戊午 | Sun fire 天上火 | Fire |

| 26 | Ji Chou 己丑 | 56 | Ji Wei 己未 | |||

| 27 | Geng Yin 庚寅 | Conifer wood 松柏木 | 57 | Geng Shen 庚申 | Pomegranate wood 石榴木 | Wood |

| 28 | Xin Mao 辛卯 | 58 | Xin You 辛酉 | |||

| 29 | Ren Chen 壬辰 | River water 长流水 | 59 | Ren Xu 壬戌 | Ocean water 大海水 | Water |

| 30 | Gui Si 癸巳 | 60 | Gui Hai 癸亥 |

Music

The Yuèlìng chapter (月令篇) of the Lǐjì (禮記) and the Huáinánzǐ (淮南子) make the following correlations:

| Movement | Wood | Fire | Earth | Metal | Water |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colour | Green | Red | Yellow | White | Black |

| Arctic Direction | east | south | center | west | north |

| Basic Pentatonic Scale pitch | 角 | 徵 | 宮 | 商 | 羽 |

| Basic Pentatonic Scale pitch pinyin | jué | zhǐ | gōng | shāng | yǔ |

| solfege | mi or E | sol or G | do or C | re or D | la or A |

- The Chinese word 青 qīng, has many meanings, including green, azure, cyan, and black. It refers to green in wuxing.

- In most modern music, various five note or seven note scales (e.g., the major scale) are defined by selecting five or seven frequencies from the set of twelve semi-tones in the Equal tempered tuning. The Chinese "lǜ" tuning is closest to the ancient Greek tuning of Pythagoras.

Martial arts

T'ai chi ch'uan uses the five elements to designate different directions, positions or footwork patterns. Either forward, backward, left, right and centre, or three steps forward (attack) and two steps back (retreat).[10]

The Five Steps (五步 wǔ bù):

- Jìn bù (進步, in simplified characters 进步) – forward step

- Tùi bù (退步) – backward step

- Zǔo gù (左顧, in simplified characters 左顾) – left step

- Yòu pàn (右盼) – right step

- Zhōng dìng (中定) – central position, balance, equilibrium

Xingyiquan uses the five elements metaphorically to represent five different states of combat.

| Movement | Fist | Chinese | Pinyin | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metal | Splitting | 劈 | Pī | To split like an axe chopping up and over |

| Water | Drilling | 鑽 / 钻 | Zuān | Drilling forward horizontally like a geyser |

| Wood | Crushing | 崩 | Bēng | To collapse, as a building collapsing in on itself |

| Fire | Pounding | 炮 | Pào | Exploding outward like a cannon while blocking |

| Earth | Crossing | 橫 / 横 | Héng | Crossing across the line of attack while turning over |

Wuxing heqidao, Gogyo Aikido (五行合气道-Chinese) is an art form with its roots in Confucian, Taoists and Buddhist theory. This art is centralised around applied peace and health studies and not that of defence or material application. The unification of mind, body and environment is emphasised using the anatomy and physiological theory of yin, yang and five-element Traditional Chinese medicine. Its movements, exercises and teachings cultivate, direct and harmonise the QI.[10]

Tea ceremony

There are spring, summer, fall, and winter teas. The perennial tea ceremony includes four tea settings (茶席) and a tea master (司茶). Each tea setting is arranged and stands for the four directions (North, South, East, and West). A vase of the seasons' flowers is put on the tea table. The tea settings are:

- Earth, 香 (Incense), yellow, center, up and down

- Wood, 春風 (Spring Wind), green, east

- Fire, 夏露 (Summer Dew), red, south

- Metal, 秋籟 (Fall Sounds), white, west

- Water, 冬陽 (Winter Sunshine) black/blue, north

Gogyo Japanese

The theory of Wuxing in Japanese culture is known as Gogyo-五行. In the 5th and 6th centuries, the principles of yin-yang and the Five Phases were transmitted to Japan from China, along with Taoism, Chinese Buddhism and Confucianism by Monks and medical physicians. Today the Theory of Gogyo is extensively used in the practice of Japanese Acupunture and traditional Kampo medicine.[16][17][18]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Wu Xing. |

Bibliography

- Feng Youlan (Yu-lan Fung), A History of Chinese Philosophy, volume 2, p. 13

- Joseph Needham, Science and Civilization in China, volume 2, pp. 262–23

- Maciocia, G. 2005, The Foundations of Chinese Medicine, 2nd edn, Elsevier Ltd., London

- Chen, Yuan (2014). "Legitimation Discourse and the Theory of the Five Elements in Imperial China". Journal of Song-Yuan Studies. 44: 325–364. doi:10.1353/sys.2014.0000.

References

- Deng Yu; Zhu Shuanli; Xu Peng; Deng Hai (2000). "五行阴阳的特征与新英译" [Characteristics and a New English Translation of Wu Xing and Yin-Yang]. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine. 20 (12): 937. Archived from the original on 2015-07-16.

- Deng Yu et al; Fresh Translator of Zang Xiang Fractal five System,Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine; 1999

- Deng Yu et al,TCM Fractal Sets 中医分形集,Journal of Mathematical Medicine ,1999,12(3),264-265

- Dr Zai, J. Taoism and Science: Cosmology, Evolution, Morality, Health and more. Ultravisum, 2015.

- Nathan Sivin (1995), "Science and Medicine in Chinese History," in his Science in Ancient China (Aldershot, England: Variorum), text VI, p. 179.

- Nathan Sivin (1987), Traditional Medicine in Contemporary China (Ann Arbor: Center for Chinese Studies, The University of Michigan) p. 73.

- 千古中医之张仲景 [Wood and Metal were often replaced with air]. Lecture Room, CCTV-10.

- Nathan Sivin (1987), Traditional Medicine in Contemporary China, p. 72.

- Chinese Five Elements Chart Archived 2007-09-28 at the Wayback Machine Information on the Chinese Five Elements from Northern Shaolin Academy in Microsoft Excel 2003 Format

- Chen, Yuan (2014). Legitimation Discourse and the Theory of the Five Elements in Imperial China. https://www.academia.edu/23276848/_Legitimation_Discourse_and_the_Theory_of_the_Five_Elements_in_Imperial_China._Journal_of_Song-Yuan_Studies_44_2014_325-364: Journal of Song-Yuan Studies.CS1 maint: location (link)

- "Traditional Chinese Medicine: In Depth". National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Archived from the original on 4 April 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

- Hafner, Christopher. "The TCM Organ Systems (Zang Fu)". University of Minnesota. Archived from the original on 6 April 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2017.

- "Five Elements Theory (Wu Xing)". Chinese Herbs Info. 2019-10-27. Retrieved 2019-12-17.

- "https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms/def/five-element-acupuncture". www.cancer.gov. 2011-02-02. Retrieved 2020-12-27. External link in

|title=(help) - Eberhard, Wolfram (December 1965). "Chinese Regional Stereotypes". Asian Survey. University of California Press. 5 (12): 596–608. doi:10.2307/2642652. JSTOR 2642652.

- "五行思想 - Translation into English - examples Japanese | Reverso Context". context.reverso.net. Retrieved 2020-12-30.

- Baracco, Luciano (2011-01-01). National Integration and Contested Autonomy: The Caribbean Coast of Nicaragua. Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-823-3.

- https://m.liaotuo.com/fjrw/jsrw/lfh/62721.html

External links

- Wuxing (Wu-hsing). The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ISSN 2161-0002.