Nose Hill Park

Nose Hill Park is a natural park in the northwest quadrant of Calgary, Alberta which covers over 11 km2 (4.2 sq mi).[1] It is the fourth-largest urban park in Canada, and one of the largest urban parks in North America.[2] It is a municipal park, unlike Fish Creek, which is a provincial park. Nose Hill Park is located in the northwest quadrant of Calgary, Alberta. It was created in 1980.[1]

| Nose Hill Park | |

|---|---|

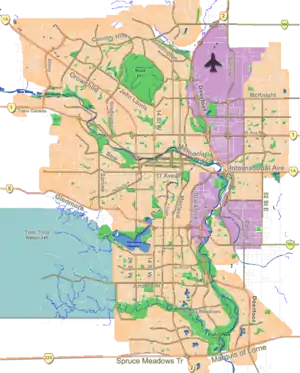

View from the summit  Location of Nose Hill in Calgary | |

| |

| Type | Urban park |

| Location | Calgary, Alberta, Canada |

| Coordinates | 51°07′N 114°07′W |

| Area | 11.27 square kilometres (4.35 sq mi) |

| Created | 1980s |

| Operated by | City of Calgary |

| Status | Open year round |

Wildlife

The park is large enough to sustain large mammals like deer and coyote as well as porcupine, northern pocket gophers, and Richardson's ground squirrels. Northern harriers and Swainson's hawks feed on smaller species such as mice and voles.[1]

Park status

In 1971 Hartel Holdings planned to develop a residential community on the site of present day Nose Hill Park and requested amendments to the prevailing zoning by-law.[3][1] In the 1970s, a grassroots group consisting of members of local communities(most notably North Haven) and Calgary Field Naturalists’ Society, later known as Nature Calgary, worked together to lobby the city to protect Nose Hill from development. In 1972 the City offered Hartel "$6873 per acre". On July 3, 1972 the City passed a resolution to defer "development of the area in question until completion of a sector plan had been made."[3] By April 16, 1973 the City restricted urban development on 4100 acres in the Nose Hill area and began investigating acquiring the land.[3] The City adopted a municipal plan for development of Nose Hill Park on March 12, 1979.[3] and a Master Plan for the park was incorporated in the City’s General Municipal Plan on June 17, 1980.[3] created a regional park with 1,129 hectares of grassland, "one of North America’s largest municipal parks."[2][3] In 1984 in Hartel Holdings vs the City of Calgary, the Supreme Court of Canada gave the City the "right to purchase land on Nose Hill at its own pace."[4]

In the 1980s Nose Hill Park was officially designated a protected area by the city.[1] Once considered the northern outskirts of Calgary, the park is today surrounded on all sides by 12 residential communities. Much has been done to preserve the park. Long-abandoned hulks of cars were removed from the coulees in the late 1970s and early 1980s.[1] Today, the park is used year-round by hikers, walkers, cyclists and other outdoor enthusiasts.

Environment

Sensitive vegetation, terrain, and archaeological sites exist within the park. It contains a significant native rough fescue grassland ecosystem and over 66 native vascular plant species have been found on the hill including parry oat grass, prairie crocus, golden bean, bedstraw and sage.

Grasslands of this nature are considered endangered in North America because more than 95 percent have been lost to cultivation, tree encroachment, pollution, and development. The grassland is one of seven major native habitat types on the hill which together provide an excellent habitat for a variety of animals. Over 198 wildlife species have been identified on the hill.

Formation

A large river flowing from the mountains to the west deposited gravels on top of sandstones and shales that formed the hill's bedrock. During the last ice age, about 15,000 years ago, ice sheets wore away the rock and gravel. At the end of the ice age, retreating ice left glacial till on the hill's top. Glacial Lake Calgary was formed in the area and deposited sediments on the side of the hill. A river, later to be known as the Bow, eroded the sediments and helped shape the south side of the hill.

History

Exposed to the drying and warming effects of the recurrent Chinook winds, Nose Hill provided favorable wintering grounds for bison herds which, in turn, attracted people to the hill's grassy slopes. The park today contains numerous tipi rings – circles of stone once used to weigh down the conical-shaped skin dwellings of plains bison hunters. Also within the perimeters of today's park are ancient tool-making stations, a stone cairn, and evidence of bison kills conducted long ago. In 1900, one Euro-Canadian settler in the Nose Hill area described the archaeological residue below the cliffs of the coulee by McPherson Creek as a bone bed nine feet thick and an acre in extent. Establishing the tribal identities of all the people who left archaeological evidence on and around Nose Hill is virtually impossible. Most of the more recent sites, however, probably belonged to the Peigan, who dominated the territory in the vicinity of the Bow Valley when the Europeans first appeared.

The origin of the hill's name is unclear but common legend tells of a European explorer asking an aboriginal translator the name of the hill seen far off in the distance. The man replied: Nose Hill is the name it was given because from here it resembles the nose of our chief.[5]

In December 1779 a well-known Hudson's Bay Company trader, Peter Fidler, recorded an excursion to the hill he went on with Peigan guides. HBC trader David Thompson wintered at a Peigan encampment on the Bow River in 1787–1788, and in 1800 returned to the area as a North West Company employee. In his journal for the year, Thompson made specific note of Nose Hill. The details of Fidler's journal entry illustrate well how dramatically the region's warm Chinook winds can affect the cold temperatures that characterize winters in southern Alberta. The temperature on the December day of Fidler's visit to Nose Hill was a balmy 14 degrees Celsius (58 degrees Fahrenheit).

John and George McDougall, Methodist missionaries, experienced more typical winter weather when they traveled to Nose Hill to hunt bison some four decades later. En route back to their hunting camp on the bitterly cold night of January 24, 1876, the elder McDougall, George, lost his way. A savage snowstorm delayed efforts to locate the missing man. On February 6, a search party finally discovered McDougall's frozen body on the east side of Nose Creek.

Names currently associated with topographical features in and near Nose Hill Park reflect the impact of the European newcomers and European trade goods on the Peigan. For example, Spy Hill, the westward extension of Nose Hill, derived its present name from the aboriginal practice of communicating with distant colleagues by flashing European trade mirrors from elevated locations. Other effects of the Europeans' arrival were more insidious. The six bison that the Methodist missionaries shot during their ill-fated hunting excursion were mere remnants of southern Alberta's once vast buffalo population. By 1879, the bison herds had vanished from Nose Hill. A new chapter of local history had begun. A fledgling Euro-Canadian community, Fort Calgary, had appeared in the valley beneath Nose Hill.

The area around Nose Hill itself played a significant economic role in Calgary's subsequent physical transformation from police fort to prairie city. Much of the sandstone used to construct the imposing public buildings that became Calgary's hallmark after 1886 came from quarries local entrepreneurs operated on Nose Creek. Stone from the J A Lewis quarry provided the entrance to the Imperial Bank and part of the new city hall erected in 1909. Masons used materials carted into the city from Nose Creek to build James Short School and Calgary's old courthouse as well.

During the construction "boom" years prior to World War I, Nose Creek also made a significant contribution to less reputable facets of the young city's economy. Bordellos built along the banks of the creek helped sustain the local prostitution trade, and further Calgary's growing notoriety as "... the booze, brothel and gambling capital of the far western plains."[6] Business at the brothels flourished until World War I, when competing downtown facilities that operated near the city's saloons and new army barracks diverted attention away from the less accessible Nose Hill and Nose Creek district.

In the fall of 1896, a young Blackfoot man, Running Weasel, died south of the Bow River. His final request provides eloquent testimony to Nose Hill's enduring role as a sentinel presiding over the passage of time. At his death, Running Weasel asked that he be " ... put where he could see the great city [of Calgary] grow beneath his feet."[7] His well-known friend Deerfoot (Blackfoot) placed his coffin beside Nose Creek.

As Calgary developed and grew, it began encroaching on the hill. Developers discussed constructing a neighborhood along the hill as early as the late 1940s. Some maps began featuring roads as far northwest as 24th Street and 48 Avenue, though none of these roads were ever constructed north of John Laurie Boulevard or west of 14th Street.[8]

Cattle grazing continued on the hill unabated until 1969. Vehicle traffic was tolerated on parts of the hill until 1971. People picnicking or just sightseeing from their cars were common sights in summer months. More than 35 years later, remnants of the damage the cars created on the narrow paths can still be seen immediately west of the Calgary Winter Club Parking lot.

A brief media sensation occurred in the summer of 2012 when an American police officer wrote a letter to the Calgary Herald lamenting that Canadian gun laws prevented him from carrying a gun in the park where he felt threatened by two men promoting the Calgary Stampede.[9]

Prior to the 15th Annual Conference of the Blackfoot Confederacy Confederacy hosted by the Kainai in Tsuu T’ina, in September, 2015, a stone marker was created adjacent to an older site of a stone cairn circle.[5][1] According to Kainai cultural Elder Andy Black Water, this was a sacred place for ceremonies and vision quests, as well as a lookout for "buffalo, the weather and danger".[5] The marker represented a Siksikaitsitapi Circle that signifies the world. The four tribes—Akainai, Siksika, Piikani and Amskapipikuni—were represented by triangle figures in each corner. Stone hoofs showed their voyages and an ochre heart lies within each Nation.[5][10]

Size and location

- 11.27 square kilometres (4.35 sq mi)[11]

- 4.8 km (3.0 mi) from North to South

- 4.0 km (2.5 mi) from East to West

- 1,125 to 1,230 m (3,691 to 4,035 ft) altitude

It is bordered on the South by John Laurie Blvd. N.W., to the West by Shaganappi Tr. N.W., on the East by 14 St. N.W., and on the North by the community of MacEwan Glen.

The park had more than 300 km (190 mi) of informal trails. The city proposed a rehabilitation plan which would provide 60 km (37 mi) of maintained trails and pathways, of which 52 km (32 mi) are dirt and gravel and 8 km (5.0 mi) are asphalt.[12]

Gallery

Downtown Calgary seen from Nose Hill

Downtown Calgary seen from Nose Hill Nose Hill's relatively flat summit

Nose Hill's relatively flat summit View of Nose Hill Park summit looking northwest

View of Nose Hill Park summit looking northwest View from Nose Hill Park looking north

View from Nose Hill Park looking north View from Nose Hill Park overlooking downtown, and facing Southeast in Spring, 2012

View from Nose Hill Park overlooking downtown, and facing Southeast in Spring, 2012 View of Calgary's skyline from the NW & facing SE in Summer, 2013

View of Calgary's skyline from the NW & facing SE in Summer, 2013

References

- City of Calgary (nd). "Nose Hill Brochure". City of Calgary. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- Sengl, Julie, ed. (2014). The City of Calgary Biodiversity Report (PDF) (Report). p. 72. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- "Hartel Holdings Co. Ltd. v. City of Calgary, [1984] 1 SCR 337, 1984 CanLII 137 (SCC)". Supreme Court of Canada (SCC). 1984.

- FONHS history

- Scout, B. (August–September 2015). "Blackfoot Confederacy marks territory with a historic landmark" (PDF). Tsinikssni. Vol. 7 no. 7. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- Gray, James (1971). Red Lights on the Prairies. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada. p. 125. OCLC 301473911.

- Calgary Herald. March 11, 1897.

- Bekin's moving – Calgary City Map (1958).

- "American tourist who lamented lack of gun during encounter in Calgary park sparks online ridicule: Walt Wawra, who felt the need to pack heat in a Calgary park has set off a storm of social media ridicule". National Post. August 9, 2012. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

- Sosiak, M. (October 28, 2015). "Sacred aboriginal landmark built in Nose hill park". Global News. Retrieved September 20, 2016.

- City of Calgary. "Nose Hill Park". Archived from the original on June 8, 2007. Retrieved July 20, 2007.

- City of Calgary (2005). "The Nose Hill Trail and Pathway Plan". Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved July 20, 2007.