Ankylosauria

Ankylosauria is a group of herbivorous dinosaurs of the order Ornithischia. It includes the great majority of dinosaurs with armor in the form of bony osteoderms, similar to turtles. Ankylosaurs were bulky quadrupeds, with short, powerful limbs. They are known to have first appeared in the early Jurassic Period, and persisted until the end of the Cretaceous Period. The two main families of Ankylosaurs, Nodosauridae and Ankylosauridae are primarily known from the Northern Hemisphere, but more basal ankylosaurs are known from the Australia-Antarctica region during the Cretaceous.

| Ankylosaurs | |

|---|---|

| |

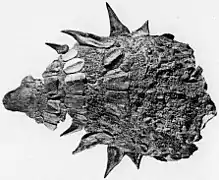

| Collection of ankylosaurs. From top left to right: Liaoningosaurus, Edmontonia, Tianzhenosaurus, Gargoyleosaurus, Scolosaurus, Denversaurus, Gastonia, Borealopelta and Akainacephalus. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Eurypoda |

| Suborder: | †Ankylosauria Osborn, 1923 |

| Subgroups | |

Ankylosauria was first named by Henry Fairfield Osborn in 1923.[1] In the Linnaean classification system, the group is usually considered either a suborder or an infraorder. It is contained within the group Thyreophora, which also includes the stegosaurs, armored dinosaurs known for their combination of plates and spikes.

Paleobiology

Armor

All ankylosaurians had armor over much of their bodies, mostly scutes and nodules, with large spines in some cases. The scutes, or plates, are rectangular to oval objects organized in transverse (side to side) rows, often with keels on the upper surface. Smaller nodules and plates filled in the open spaces between large plates. In all three groups, the first two rows of plates tend to form a sort of half-ring around the neck; in nodosaurids, this comes from adjacent plates fusing with each other (and there is a third row as well), while ankylosaurids usually have the plates fused to the top of another band of bone. The skull has armor plastered on to it, including a distinctive piece on the outside-rear of the lower jaw.

Diet and feeding

Ankylosaurs were built low to the ground, typically one foot off the ground surface. They had small, triangular teeth that were loosely packed, similar to stegosaurs. The large hyoid bones left in skeletons indicates that they had long, flexible tongues. They also had a large, side secondary palate. This means that they could breathe while chewing, unlike crocodiles. Their expanded gut region suggests the use of fermentation to digest their food, using symbiotic bacteria and gut flora. Their diet likely consisted of ferns, cycads, and angiosperms. Mallon et al. (2013) examined herbivore coexistence on the island continent of Laramidia during the Late Cretaceous. It was concluded that ankylosaurs were generally restricted to feeding on vegetation at, or below, the height of 1 meter.[2]

Reproduction

Possible neonate-sized ankylosaur fossils have been documented in the scientific literature.[3]

Brain

Members of Ankylosauria sported a very small brain size in proportion to their body, second only to the Saurischian sauropods.

Movement

Ankylosaurs were slow moving, largely because of the shortness of the limbs combined with being incapable of running. Their top speed was likely less than 10 km/h (2.8 m/s; 6.2 mph).

Classification

Ankylosauria is usually split into two families: Nodosauridae (the nodosaurids) and Ankylosauridae (the ankylosaurids). A third family, the Polacanthidae, is sometimes used,[4] but is more often found to be a sub-group of one of the primary families.[5]

The first formal definition of Ankylosauria as a clade, a group containing all species of a certain evolutionary branch, was given in 1997 by Carpenter.[6] He defined the group as all dinosaurs (more precisely: all thyreophoran Ornithischia) closer to Ankylosaurus than to Stegosaurus. This definition is essentially followed by most paleontologists today. This "stem-based" definition means that the primitive armored dinosaur Scelidosaurus, which is slightly closer to ankylosaurids than to stegosaurids, is technically a member of Ankylosauria. Upon the discovery of Bienosaurus, Dong Zhiming (2001) erected the family Scelidosauridae for both of these primitive ankylosaurs.[7] In 2001, Carpenter proposed a new group uniting Scelidosaurus, Ankylosauridae, Nodosauridae, and Polacanthidae, with Minmi (thought to be a primitive ankylosaurian), to the exclusion of Stegosaurus.[8] However, many taxonomists find that Ankylosauromorpha is an invalid group.[9]

Nodosauridae

This group traditionally includes Nodosaurus, Edmontonia, and Sauropelta. The nodosauridae had longer snouts than their ankylosaurid cousins. They did not sport the archetypal 'clubs' at the ends of their tails; but, rather, their most pronounced physical features were their spikes.

Nodosaurids had very muscular shoulders and a specialized knob of bone on each shoulder blade called the acromial process. It served as an attachment site for the muscles that held up their large parascapular spines. These spines would be used for self-defense against predators. They also had wide, flaring hips and thick limbs. They had smaller, narrow beaks than the ankylosaurids, which likely allowed them to be very selective over what plant matter they grazed on.

Most nodosaurid finds are from North America.

Ankylosauridae

Major differences distinguishing the ankylosaurids from the nodosaurids is that the ankylosaurids had bony clubs at the end of their tails, domed snouts in front of the eyes, and large squamosal plates projecting from the top and bottom of each side of the skull, all of which nodosaurids lacked. The traditional ankylosaurids are from later in the Cretaceous. They had much wider bodies and have even been discovered with bony eyelids. The large clubs at the end of their tails may have been used in self-defense (swung at predators) or in sexual selection. This family included Ankylosaurus, Euoplocephalus, and Pinacosaurus. The clubs were made of several plates of bone that were permeated by soft tissue, allowing them to absorb thousands of pounds of force. Their beaks were larger and broader than the nodosaurids, indicating that these ankylosaurs were generalists in their diet.

Polacanthidae

The family Polacanthidae was named by George Reber Wieland in 1911 to refer to a group of ankylosaurs that seemed to him to be intermediate between the ankylosaurids and nodosaurids.[10] This grouping was ignored by most researchers until the late 1990s, when it was used as a subfamily (Polacanthinae) by Kirkland for a natural group recovered by his 1998 analysis suggesting that Polacanthus, Gastonia, and Mymoorapelta were closely related within the family Ankylosauridae. Kenneth Carpenter resurrected the name Polacanthidae for a similar group that he also found to be closer to ankylosaurids than to nodosaurids. Carpenter became the first to define Polacanthidae as all dinosaurs closer to Gastonia than to either Edmontonia or Euoplocephalus.[11] Most subsequent researchers placed polacanthines as primitive ankylosaurids, though mostly without any rigorous study to demonstrate this idea. The first comprehensive study of 'polacanthid' relationships, published in 2012, found that they are either an unnatural grouping of primitive nodosaurids, or a valid subfamily at the base of Nodosauridae.[5]

Taxonomy

While ranked taxonomy has largely fallen out of favor among dinosaur paleontologists, a few 21st-century publications have retained the use of ranks, though sources have differed on what its rank should be. Most have listed Thyreophora as an unranked taxon containing the traditional suborders Stegosauria and Ankylosauria, though Thyreophora is also sometimes classified as a suborder, with Ankylosauria and Stegosauria as infraorders. A simplified version of one possible classification follows:

- Order Ornithischia (the "bird hipped" dinosaurs)

- Clade Thyreophora (armored dinosaurs)

- Clade Eurypoda (advanced armored dinosaurs)

- Clade Ankylosauria

- Family Ankylosauridae

- Subfamily Ankylosaurinae

- Family Nodosauridae

- Subfamily Polacanthinae?

- Family Ankylosauridae

- Clade Ankylosauria

- Clade Eurypoda (advanced armored dinosaurs)

- Clade Thyreophora (armored dinosaurs)

See also

References

- Osborn, H. F. (1923). "Two Lower Cretaceous dinosaurs of Mongolia." American Museum Novitates, 95: 1–10.

- Mallon, Jordan C; David C Evans; Michael J Ryan; Jason S Anderson (2013). "Feeding height stratification among the herbivorous dinosaurs from the Dinosaur Park Formation (upper Campanian) of Alberta, Canada". BMC Ecology. 13: 14. doi:10.1186/1472-6785-13-14. PMC 3637170. PMID 23557203.

- Tanke, D.H. and Brett-Surman, M.K. 2001. Evidence of Hatchling and Nestling-Size Hadrosaurs (Reptilia:Ornithischia) from Dinosaur Provincial Park (Dinosaur Park Formation: Campanian), Alberta, Canada. pp. 206-218. In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life—New Research Inspired by the Paleontology of Philip J. Currie. Edited by D.H. Tanke and K. Carpenter. Indiana University Press: Bloomington. xviii + 577 pp.

- Hayashi, S., Carpenter, K., Scheyer, T.M., Watabe, M. and Suzuki. D. (2010). "Function and evolution of ankylosaur dermal armor." Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 55(2): 213-228. doi:10.4202/app.2009.0103

- Thompson, R.S., Parish, J.C., Maidment, S.C.R. and Barrett, P.M. (2012). "Phylogeny of the ankylosaurian dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Thyreophora)." Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, 10(2): 301-312. doi:10.1080/14772019.2011.569091

- Carpenter, K., 1997, "Ankylosauria" pp. 16-20 in: P.J. Currie and K. Padian (eds.), Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs, Academic Press, San Diego

- Dong Zhiming (2001). "Primitive Armored Dinosaur from the Lufeng Basin, China". In Tanke, Darren H.; Carpenter, Kenneth (eds.). Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Indiana University Press. pp. 237–243. ISBN 0-253-33907-3.

- Carpenter, K. (2001). "Phylogenetic Analysis of the Ankylosauria". In Carpenter, Kenneth (ed.). The Armored Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. p. 455. ISBN 0-253-33964-2.

- Maidment, S.C.R; Wei, G.; Norman, D.B. (2006). "Re-description of the postcranial skeleton of the middle Jurassic stegosaur Huayangosaurus taibaii". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 26 (4): 944–956. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[944:ROTPSO]2.0.CO;2.

- G.R. Wieland, 1911, "Notes on the armored Dinosauria", The American Journal of Science, series 4 31: 112-124

- Carpenter K (2001). "Phylogenetic analysis of the Ankylosauria". In Carpenter, Kenneth (ed.). The Armored Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 455–484. ISBN 0-253-33964-2.