Panopticon

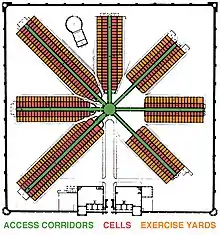

The panopticon is a type of institutional building and a system of control designed by the English philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham in the 18th century. The concept of the design is to allow all prisoners of an institution to be observed by a single security guard, without the inmates being able to tell whether they are being watched.

Although it is physically impossible for the single guard to observe all the inmates' cells at once, the fact that the inmates cannot know when they are being watched means that they are motivated to act as though they are being watched at all times. Thus, the inmates are effectively compelled to regulate their own behaviour. The architecture consists of a rotunda with an inspection house at its centre. From the centre, the manager or staff of the institution are able to watch the inmates. Bentham conceived the basic plan as being equally applicable to hospitals, schools, sanatoriums, and asylums, but he devoted most of his efforts to developing a design for a panopticon prison. It is his prison that is now most widely meant by the term "panopticon".

Conceptual history

The word panopticon derives from the Greek word for "all seeing" – panoptes.[3] In 1785, Jeremy Bentham, an English social reformer and founder of utilitarianism, travelled to Krichev in White Russia (modern Belarus) to visit his brother, Samuel, who accompanied Prince Potemkin.[4]:xxxviii Bentham arrived in Krichev in early 1786[5] and stayed for almost two years. While residing with his brother in Krichev, Bentham sketched out the concept of the panopticon in letters. Bentham applied his brother's ideas on the constant observation of workers to prisons. Back in England, Bentham, with the assistance of his brother, continued to develop his theory on the panopticon.[4]:xxxviii Prior to fleshing out his ideas of a panopticon prison, Bentham had drafted a complete penal code and explored fundamental legal theory. While in his lifetime Bentham was a prolific letter writer, he published little and remained obscure to the public until his death.[4]:385

Bentham thought that the chief mechanism that would bring the manager of the panopticon prison in line with the duty to be humane would be publicity. Bentham tried to put his duty and interest junction principle into practice by encouraging a public debate on prisons. Bentham's inspection principle applied not only to the inmates of the panopticon prison, but also the manager. The unaccountable gaoler was to be observed by the general public and public officials. The apparently constant surveillance of the prison inmates by the panopticon manager and the occasional observation of the manager by the general public was to solve the age old philosophic question: "Who guards the guards?"[6]

Bentham continued to develop the panopticon concept, as industrialisation advanced in England and an increasing number of workers were required to work in ever larger factories.[7] Bentham commissioned drawings from an architect, Willey Reveley. Bentham reasoned that if the prisoners of the panopticon prison could be seen but never knew when they were watched, the prisoners would need to follow the rules. Bentham also thought that Reveley's prison design could be used for factories, asylums, hospitals, and schools.[8]

Bentham remained bitter throughout his later life about the rejection of the panopticon scheme, convinced that it had been thwarted by the king and an aristocratic elite. It was largely because of his sense of injustice and frustration that he developed his ideas of sinister interest – that is, of the vested interests of the powerful conspiring against a wider public interest – which underpinned many of his broader arguments for reform.[9]

Prison design

The Building circular – an iron cage, glazed – a glass lantern about the size of Ranelagh – The Prisoners in their Cells, occupying the Circumference – The Officers, the Centre. By Blinds, and other contrivances, the Inspectors concealed from the observation of the Prisoners: hence the sentiment of a sort of invisible omnipresence. – The whole circuit reviewable with little, or, if necessary, without any, change of place.[10]

— Jeremy Bentham (1791). Panopticon, or The Inspection House

.jpg.webp)

Bentham's proposal for a panopticon prison met with great interest among British government officials not only because it incorporated the pleasure-pain principle developed by the materialist philosopher Thomas Hobbes, but also because Bentham joined the emerging discussion on political economy. Bentham argued that the confinement of the prison, "which is his punishment, preventing [the prisoner from] carrying the work to another market." Key to Bentham's proposals and efforts to build a panopticon prison in Millbank at his own expense, was the "means of extracting labour" out of prisoners in the panopticon.[11] In his 1791 writing Panopticon, or The Inspection House, Bentham reasoned that those working fixed hours needed to be overseen.[12] Also, in 1791 Jean Philippe Garran de Coulon presented a paper on Bentham's panopticon prison concepts to the National Legislative Assembly in revolutionary France.[13]

In 1812 persistent problems with Newgate Prison and other London prisons prompted the British government to fund the construction of a prison in Millbank at the taxpayers' expense. Based on Bentham's panopticon plans, the National Penitentiary opened in 1821. Millbank Prison, as it became known, was controversial and failed in extracting valuable labour out of prisoners. Millbank Prison was even blamed for causing mental illness among prisoners. Nevertheless, the British government placed an increasing emphasis on prisoners doing meaningful work, instead of engaging in humiliating and meaningless kill-times.[11] Bentham lived to see Millbank Prison built and did not support the approach taken by the British government. His writings had virtually no immediate effect on the architecture of taxpayer-funded prisons that were to be built. Between 1818 and 1821 a small prison for women was built in Lancaster. It has been observed that the architect Joseph Gandy modelled it very closely on Bentham's panopticon prison plans. The K-wing near Lancaster Castle prison is a semi-rotunda with a central tower for the supervisor and five storeys with nine cells on each floor.[14]

It was the Pentonville prison, which was built in London after Bentham's death in 1832, that was to serve as a model for a further 54 prisons in Victorian Britain. Built between 1840 and 1842 according to the plans of Joshua Jebb, Pentonville prison had a central hall with radial prison wings.[14] It has been claimed that Bentham's panopticon influenced the radial design of 19th-century prisons built on the principles of the "separate system", including Eastern State Penitentiary in Philadelphia, which opened in 1829.[15] But the Pennsylvania–Pentonville architectural model with its radial prison wings was not designed to facilitate constant surveillance of individual prisoners. Guards had to walk from the hall along the radial corridors and could only observe prisoners in their cells by looking through the cell door's peephole.[16]

In 1925 Cuba's president Gerardo Machado set out to build a modern prison, based on Bentham's concepts and employing the latest scientific theories on rehabilitation. A Cuban envoy tasked with studying US prisons in advance of the construction of Presidio Modelo had been greatly impressed with Stateville Correctional Center in Illinois and the cells in the new circular prison were to faced inwards towards a central guard tower. Because of the shuttered guard tower the guards could see the prisoners, but the prisoners could not see the guards. Cuban officials theorised that the prisoners would "behave" if there was a probable chance that they were under surveillance and once prisoners behaved they could be rehabilitated.

Between 1926 and 1931 the Cuban government built four such panopticons connected with tunnels to a massive central structure that served as a community centre. Each panopticon had five floors with 93 cells. In keeping with Bentham's ideas, none of the cells had doors. Prisoners were free to roam the prison and participate in workshops to learn a trade or become literate, the hope being that they would become productive citizens. However, by the time Fidel Castro was imprisoned at Presidio Modelo, the four circulars were packed with 6,000 men, every floor was filled with trash, there was no running water, food rations were meagre, and the government supplied only the bare necessities of life.[17]

In the Netherlands Breda, Arnhem and Haarlem penitentiary are cited as historic panopticon prisons. However, these circular prisons with their 400 or so cells fail as panopticons because the inwards-facing cell windows were so small that guards could not see the entire cell. The lack of surveillance that was actually possible in prisons with small cells and doors discounts many circular prison designs from being a panopticon as it had been envisaged by Bentham.[18] In 2006 one of the first digital panopticon prisons opened near Amsterdam. Every prisoner in the Lelystad Prison wears an electronic tag and by design, only six guards are needed for 150 prisoners instead of the usual 15 or more.[18]

Architecture of other institutions

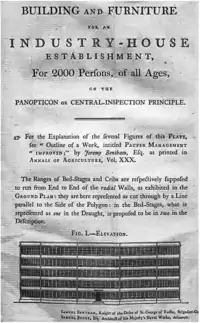

Jeremy Bentham's panopticon architecture was not original, as rotundas had been used before, as for example in industrial buildings. However, Bentham turned the rotund architecture into a structure with a societal function, so that humans themselves became the object of control.[19] The idea for a panopticon had been prompted by his brother Samuel Bentham's work in Russia and had been inspired by existing architectural traditions. Samuel Bentham had studied at the Ecole Militaire in 1751, and at about 1773 the prominent French architect Claude-Nicolas Ledoux had finished his designs for the Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans.[20] William Strutt in cooperation with his friend Jeremy Bentham built a round mill in Belper, so that one supervisor could oversee an entire shop floor from the centre of the round mill. The mill was built between 1803 and 1813 and was used for production until the late 19th century. It was demolished in 1959.[21] In Bentham's 1812 writing Pauper management improved: particularly by means of an application of the Panopticon principle of construction, he included a building for an "industry-house establishment" that could hold 2000 persons.[22] In 1812 Samuel Bentham, who had by then risen to brigardier-general, tried to persuade the British Admiralty to construct an arsenal panopticon in Kent. Before returning home to London he had constructed a panopticon in 1807, near St Petersburg, which served as a training centre for young men wishing to work in naval manufacturing.[23] The panopticon, Bentham writes:

will be found applicable, I think, without exception to all establishments whatsoever, in which within a space not too large to be covered or commanded by buildings, a number of persons are meant ot be kept under inspections. No matter how different or even opposite the purpose.[24]

— Jeremy Bentham (1791). Panopticon, or The Inspection House

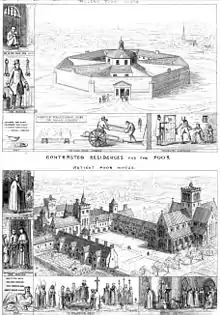

Despite the fact that no panopticon was built during Bentham's lifetime, the principles he established on the panopticon prompted considerable discussion and debate. Shortly after Jeremy Bentham's death in 1832 his ideas were criticised by Augustus Pugin, who in 1841 published the second edition of his work Contrasts in which one plate showed a "Modern Poor House". He contrasted an English medieval gothic town in 1400 with the same town in 1840 where broken spires and factory chimneys dominate the skyline, with a panopticon in the foreground replacing the Christian hospice. Pugin, who went on to become one of the most influential 19th-century writers on architecture, was influenced by Hegel and German idealism.[25] In 1835 the first annual report of the Poor Law Commission included two designs by the commission's architect Sampson Kempthorne. His Y-shape and cross-shape designs for workhouse expressed the panopticon principle by positioning the master's room as central point. The designs provided for the segregation of occupants and maximum visibility from the centre.[26] Professor David Rothman came to the conclusion that Bentham's panopticon prison did not inform the architecture of early asylums in the United States.[27]

Criticism and use as metaphor

In 1965 the conservative historian Shirley Robin Letwin traced the Fabian zest for social planning to early utilitarian thinkers. She argued that Bentham's pet gadget, the panopticon prison, was a device of such monstrous efficiency that it left no room for humanity. She accused Bentham of forgetting the dangers of unrestrained power and argued that "in his ardour for reform, Bentham prepared the way for what he feared". Recent Libertarian thinkers began to regard Bentham's entire philosophy as having paved the way for totalitarian states.[28] In the late 1960s, the American historian Gertrude Himmelfarb, who had published The Haunted House of Jeremy Bentham in 1965, was at the forefront of depicting Bentham's mechanism of surveillance as a tool of oppression and social control.[29][28] David John Manning published The Mind of Jeremy Bentham in 1986, in which he reasoned that Bentham's fear of instability caused him to advocate ruthless social engineering and a society in which there could be no privacy or tolerance for the deviant.[28]

In the mid-1970s, the panopticon was brought to the wider attention by the French psychoanalyst Jacques-Alain Miller and the French philosopher Michel Foucault.[30] In 1975 Foucault used the panopticon as metaphor for the modern disciplinary society in Discipline and Punish. He argued that the disciplinary society had emerged in the 18th century and that discipline are techniques for assuring the ordering of human complexities, with the ultimate aim of docility and utility in the system.[31] Foucault first came across the panopticon architecture when he studied the origins of clinical medicine and hospital architecture in the second half of the 18th century. He argued that discipline had replaced the pre-modern society of kings, and that the panopticon should not be understood as a building, but as a mechanism of power and a diagram of political technology.[31]

Foucault argued that discipline had crossed the technological threshold already in the late 18th century, when the right to observe and accumulate knowledge had been extended from the prison to hospitals, schools, and later factories.[31] In his historic analysis, Foucault reasoned that with the disappearance of public executions pain had been gradually eliminated as punishment in a society ruled by reason.[31] The modern prison in the 1970s, with its corrective technology, was rooted in the changing legal powers of the state. While acceptance for corporal punishment diminished, the state gained the right to administer more subtle methods of punishment, such as to observe.[31] The French sociologist Henri Lefebvre studied urban space and Foucault's interpretation of the panopticon prison, arriving at the conclusion that spatiality is a social phenomenon. Lefebvre contended, that architecture is no more than the relationship between the panopticon, people, and objects. In urban studies, academics such as Marc Schuilenburg now argue that a different self-consciousness arises among humans who live in an urban area.[32]

In 1984 Michael Radford gained international attention for the cinematographic panopticon he had staged in the film Nineteen Eighty-Four. Of the telescreens in the landmark surveillance narrative Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), George Orwell said: "there was of course no way of knowing whether you were being watched at any given moment ... you had to live ... in the assumption that every sound you made was overheard, and, except in darkness, every movement scrutinised".[33] In Radford's film the telescreens were bidirectional and in a world with an ever increasing number of telescreen devices the citizens of Oceania were spied on more than they thought possible.[34] In The Electronic Eye: The Rise of Surveillance Society (1994) the sociologist David Lyon concluded that "no single metaphor or model is adequate to the task of summing up what is central to contemporary surveillance, but important clues are available in Nineteen Eighty-Four and in Bentham's panopticon".[35]

The French philosopher Gilles Deleuze shaped the emerging field of surveillance studies with the 1990 essay Postscript on the Societies of Control.[36]:21 Deleuze argued that the society of control is replacing the discipline society. With regards to the panopticon, Deleuze argued that "enclosures are moulds ... but controls are a modulation". Deleuze observed that technology had allowed physical enclosures, such as schools, factories, prisons and office buildings, to be replaced by a self-governing machine, which extends surveillance in a quest to manage production and consumption. Information circulates in the control society, just like products in the modern economy, and meaningful objects of surveillance are sought out as forward-looking profiles and simulated pictures of future demands, needs and risks are drawn up.[36]:27

In 1997 Thomas Mathiesen in turn expanded on Foucault's use of the panopticon metaphor when analysing the effects of mass media on society. He argued that mass media such as broadcast television gave many people the ability to view the few from their own homes and gaze upon the lives of reporters and celebrities. Mass media has thus turned the discipline society into a viewer society.[37] In the 1998 satirical science fiction film The Truman Show, the protagonist eventually escapes the OmniCam Ecosphere, the reality television show that, unknown to him, broadcasts his life around the clock and across the globe. But in 2002 Peter Weibel noted that the entertainment industry does not consider the panopticon as a threat or punishment, but as "amusement, liberation and pleasure". With reference to the Big Brother television shows of Endemol Entertainment, in which a group of people live in a container studio apartment and allow themselves to be recorded constantly, Weibel argued that the panopticon provides the masses with "the pleasure of power, the pleasure of sadism, voyeurism, exhibitionism, scopophilia, and narcissism". In 2006, Shoreditch TV became available to residents of the Shoreditch in London, so that they could tune in to watch CCTV footage live. The service allowed residents "to see what's happening, check out the traffic and keep an eye out for crime".[38]

In their 2004 book Welcome to the Machine: Science, Surveillance, and the Culture of Control, Derrick Jensen and George Draffan called Bentham "one of the pioneers of modern surveillance" and argued that his panopticon prison design serves as the model for modern supermaximum security prisons, such as Pelican Bay State Prison in California.[39] In the 2015 book Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness, Simone Browne noted that Bentham travelled on a ship carrying slaves as cargo while drafting his panopticon proposal. She argues that the structure of chattel slavery haunts the theory of the panopticon. She proposes that the 1789 plan of the slave ship Brookes should be regarded as the paradigmatic blueprint.[40] Drawing on Didier Bigo's Banopticon, Brown argues that society is ruled by exceptionalism of power, where the state of emergency becomes permanent and certain groups are excluded on the basis of their future potential behaviour as determined through profiling.[41]

Surveillance technology

The metaphor of the panopticon prison has been employed to analyse the social significance of surveillance by closed-circuit television (CCTV) cameras in public spaces. In 1990, Mike Davis reviewed the design and operation of a shopping mall, with its centralised control room, CCTV cameras and security guards, and came to the conclusion that it "plagiarizes brazenly from Jeremy Bentham's renowned nineteenth-century design". In their 1996 study of CCTV camera installations in British cities, Nicholas Fyfe and Jon Bannister called central and local government policies that facilitated the rapid spread of CCTV surveillance a dispersal of an "electronic panopticon". Particular attention has been drawn to the similarities of CCTV with Bentham's prison design because CCTV technology enabled, in effect, a central observation tower, staffed by an unseen observer.[42]:249

Employment and management

Shoshana Zuboff used the metaphor of the panopticon in her 1988 book In the Age of the Smart Machine: The Future of Work and Power to describe how computer technology makes work more visible. Zuboff examined how computer systems were used for employee monitoring to track the behavior and output of workers. She used the term 'panopticon' because the workers could not tell that they were being spied on, while the manager was able to check their work continuously. Zuboff argued that there is a collective responsibility formed by the hierarchy in the information panopticon that eliminates subjective opinions and judgements of managers on their employees. Because each employee's contribution to the production process is translated into objective data, it becomes more important for managers to be able to analyze the work rather than analyze the people.[43]

Foucault's use of the panopticon metaphor shaped the debate on workplace surveillance in the 1970s. In 1981 the sociologist Anthony Giddens expressed scepticism about the ongoing surveillance debate, criticising that "Foucault's 'archaeology', in which human beings do not make their own history but are swept along by it, does not adequately acknowledge that those subject to the power ... are knowledgeable agents, who resist, blunt or actively alter the conditions of life."[42]:39 The social alienation of workers and management in the industrialised production process had long been studied and theorised. In the 1950s and 1960s, the emerging behavioural science approach led to skills testing and recruitment processes that sought out employees that would be organisationally committed. Fordism, Taylorism and bureaucratic management of factories was still assumed to reflect a mature industrial society. The Hawthorne Plant experiments (1924–1933) and a significant number of subsequent empirical studies led to the reinterpretation of alienation: instead of being a given power relationship between the worker and management, it came to be seen as hindering progress and modernity.[44] The increasing employment in the service industries has also been re-evaluated. In Entrapped by the electronic panopticon? Worker resistance in the call centre (2000), Phil Taylor and Peter Bain argue that the large number of people employed in call centres undertake predictable and monotonous work that is badly paid and offers few prospects. As such, they argue, it is comparable to factory work.[45]:15

The panopticon has become a symbol of the extreme measures that some companies take in the name of efficiency as well as to guard against employee theft. Time-theft by workers has become accepted as an output restriction and theft has been associated by management with all behaviour that include avoidance of work. In the past decades "unproductive behaviour" has been cited as rationale for introducing a range of surveillance techniques and the vilification of employees who resist them.[45]:x In a 2009 paper by Max Haiven and Scott Stoneman entitled Wal-Mart: The Panopticon of Time[46] and the 2014 book by Simon Head Mindless: Why Smarter Machines Are Making Dumber Humans, which describes conditions at an Amazon depot in Augsburg, it is argued that catering at all times to the desires of the customer can lead to increasingly oppressive corporate environments and quotas in which many warehouse workers can no longer keep up with demands of management.[47]

Social media

The concept of panopticon has been referenced in early discussions about the impact of social media. The notion of dataveillance was coined by Roger Clarke in 1987, since then academic researchers have used expressions such as superpanopticon (Mark Poster 1990), panoptic sort (Oscar H. Gandy Jr. 1993) and electronic panopticon (David Lyon 1994) to describe social media. Because the controlled is at the center and surrounded by those who watch, early surveillance studies treat social media as a reverse panopticon.[48]

In modern academic literature on social media, terms like lateral surveillance, social searching, and social surveillance are employed to critically evaluate the effects of social media. However, the sociologist Christian Fuchs treats social media like a classical panopticon. He argues that the focus should not be on the relationship between the users of a medium, but the relationship between the users and the medium. Therefore, he argues that the relationship between the large number of users and the sociotechnical Web 2.0 platform, like Facebook, amounts to a panopticon. Fuchs draws attention to the fact that use of such platforms requires identification, classification and assessment of users by the platforms and therefore, he argues, the definition of privacy must be reassessed to incorporate stronger consumer protection and protection of citizens from corporate surveillance.[48]

The arts and literature

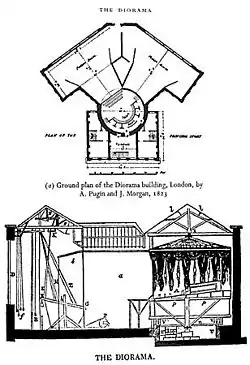

According to professor Donald Preziosi, the panopticon prison of Bentham resonates with the memory theatre of Giulio Camillo, where the sitting observer is at the centre and the phenomena are categorised in an array, which makes comparison, distinction, contrast and variation legible.[49] Among the architectural references Bentham quoted for his panopticon prison was Ranelagh Gardens, a London pleasure garden with a dome built around 1742. At the center of the rotunda beneath the dome was an elevated platform from which a 360 degrees panorama could be viewed, illuminated through skylights.[50] Professor Nicholas Mirzoeff compares the panopticon with the 19th-century diorama, because the architecture is arranged so that the seer views cells or galleries.[51]

In 1854 the work on the building that was to house the Royal Panopticon of Science and Art in London was completed. The rotunda at the centre of the building was encircled with a 91 meter procession. The interior reflected the taste for religiously meaningless ornament and emerged out of the contemporary taste for recreational learning. Visitors of the Royal Panopticon of Science and Art could view changing exhibits, including vacuum flasks, a pin making machine and a cook stove. However, a competitive entertainment industry emerged in London[52] and despite the varying music, the large fountains, interesting experiments and opportunities for shopping,[53] two years after opening the amateur science panopticon project closed.[54]

Panopticon principle lies as the central idea in the plot of We (novel) (Russian: Мы, romanized: My), a dystopian novel by Russian writer Yevgeny Zamyatin, written 1920–1921. Zamyatin goes beyond a concept of a single prison and projects panopticon principles to the whole society where people live in buildings with fully transparent walls.

Foucault's theories positioned Bentham's panopticon prison in the social structures of 1970s Europe. This led to the widespread use of the panopticon in literature, comic books, computer games, and TV series.[55] In Doctor Who, an abandoned panopticon was featured.[56] In 1981 the novella Chronicle of a Death Foretold by Gabriel García Márquez on the murder of Santiago Nasar, chapter four is written with a view on the characters through the panopticon prison of Riohacha.[57] Angela Carter, in her 1984 novel Nights at the Circus, linked the panopticon of Countes P to a "perverse honeycomb" and made the character the matriarchal queen bee.[58] In the 2011 TV series, Person of Interest, Foucault's panopticon is used to grasp the pressure under which the character Harold Finch suffers in the post-9/11 United States of America.[59]

See also

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

References

- Bentham Papers 119a/119. UCL Press. p. 137.

- Bentham Papers 119a/119. UCL Press. p. 139.

- Alan Briskin (1998). Stirring of Soul in the Workplace. Berrett-Koehler Publishers. p. 77. ISBN 9781605096162.

- Sprigge, Timothy L. S.; Burns, J. H., eds. (2017). Correspondence of Jeremy Bentham, Volume 1: 1752 to 1776. UCL Press. ISBN 9781911576051.

- Gillian Darley (2003). Factory. Reaktion Books. pp. 52. ISBN 9781861891556.

- James E. Crimmins (2017). The Bloomsbury Encyclopedia of Utilitarianism. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 396. ISBN 9781350021686.

- Alan Briskin (1998). Stirring of Soul in the Workplace. Berrett-Koehler Publishers. p. 78. ISBN 9781605096162.

- Gold, Joel; Gold, Ian (2015). Suspicious Minds: How Culture Shapes Madness. Simon and Schuster. p. 210. ISBN 9781439181560.

- Philip Schofield (2009). Bentham: a guide for the perplexed. London: Continuum. pp. 90–93. ISBN 978-0-8264-9589-1.

- Humphrey Jennings (2012). Pandaemonium 1660–1886: The Coming of the Machine as Seen by Contemporary Observers. Icon Books. ISBN 9781848315860.

- Gary Kelly (2017). Newgate Narratives. Routledge. ISBN 9781351221405.

- Gillian Darley (2003). Factory. Reaktion Books. pp. 53. ISBN 9781861891556.

- Dan Edelstein (2010). The Terror of Natural Right: Republicanism, the Cult of Nature, and the French Revolution. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226184395.

- Jonathan Simon (2016). Architecture and Justice: Judicial Meanings in the Public Realm. Routledge. p. 43. ISBN 9781317179382.

- Andrzejewski, Anna Vemer (2008). Building Power: Architecture and Surveillance in Victorian America. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-1-57233631-5.

- Jacqueline Z. Wilson (2008). Prison: Cultural Memory and Dark Tourism. Peter Lang. p. 37. ISBN 9781433102790.

- Wallace, Robert; Melton, H. Keith; Schlesinger, Henry R. (2008). Spycraft: The Secret History of the CIA's Spytechs, from Communism to Al-Qaeda. Penguin. pp. 258–259. ISBN 9781440635304.

- Maly, Tim; Horne, Emily (2014). The Inspection House: An Impertinent Field Guide to Modern Surveillance. Coach House Books. pp. 28–29. ISBN 9781552453018.

- Luigi Vessella (2017). Open Prison Architecture: Design Criteria for a New Prison Typology. WITPress. p. 10. ISBN 9781784662479.

- Donald Preziosi (1989). Rethinking Art History: Meditations on a Coy Science. Yale University Press. p. 65-66. ISBN 9780300049831.

- Adrian Farmer (2013). Belper From Old Photographs. Amberley Publishing Limited. p. 155. ISBN 9781445619620.

- Jonathan Simon (1989). Architecture and Justice: Judicial Meanings in the Public Realm. Routledge. p. 44. ISBN 9781317179382.

- Gillian Darley (2003). Factory. Reaktion Books. pp. 54. ISBN 9781861891556.

- Jeremy Bentham (1791). Panopticon Or the Inspection House, Volume 2. London.

- Trevor Garnham (2013). Architecture Re-assembled: The Use (and Abuse) of History. Routledge. p. 47. ISBN 9781134052998.

- Tarlow, Sarah; West, Susie (2002). Familiar Past?: Archaeologies of Later Historical Britain. Routledge. p. 131 & 134. ISBN 9781134660346.

- David Rothman (2017). The Discovery of the Asylum: Social Order and Disorder in the New Republic. Routledge. p. xliv. ISBN 9781351483643.

- Semple, Janet (1993). Bentham's Prison: A Study of the Panopticon Penitentiary. Clarendon Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 9780191590818.

- Himmelfarb, Gertrude (1965). "The Haunted House of Jeremy Bentham". In Herr, Richard; Parker, Harold T. (eds.). Ideas in History: essays presented to Louis Gottschalk by his former students. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press.

- Božovič, Miran (2000). An Utterly Dark Spot: Gaze and Body in Early Modern Philosophy. University of Michigan Press. p. 95. ISBN 9780472111404.

- Fontana-Giusti, Gordana (2013). Foucault for Architects. Routledge. p. 89–92. ISBN 9781135010096.

- de Jong, Alex; Schuilenburg, Marc (2006). Mediapolis: Popular Culture and the City. 010 Publishers. p. 146. ISBN 9789064506284.

- Orwell, George (1989) [1949]. Nineteen Eighty-Four. Penguin. pp. 4, 5.

- Lefait, Sebastien (2013). Surveillance on Screen: Monitoring Contemporary Films and Television Programs. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 24. ISBN 9780810885905.

- Lyon, David (1994). The Electronic Eye: The Rise of Surveillance Society. University of Minnesota Press. p. 78. ISBN 9781452901732.

- Ball, Kirstie; Lyon, David; Haggerty, Kevin D. (2012). Routledge Handbook of Surveillance Studies. Routledge. ISBN 9780415588836.

- Casey B. Hart, ed. (2017). The Evolution and Social Impact of Video Game Economics. Lexington Books. p. 57. ISBN 9781498543422.

- Walz, Steffen P. (2010). Toward a Ludic Architecture: The Space of Play and Games. Lulu. p. 258. ISBN 9780557285631.

- Jensen, Derrick; Draffan, George (2004). Welcome to the Machine: Science, Surveillance, and the Culture of Control. Chelsea Green Publishing. pp. 8–9. ISBN 9781931498524.

- Browne, Simone (2015). Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822359197.

- Coleman, Mat; Agnew, John (2012). Handbook on the Geographies of Power. Edward Elgar Publishing. p. 77. ISBN 9781785365645.

- Lyon, David (2003). Surveillance as Social Sorting: Privacy, Risk, and Digital Discrimination. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415278737.

- Zuboff, Shoshana (1988). In the Age of the Smart Machine: The Future of Work and Power (PDF). Basic Books. pp. 315–361.

- Grieves, Jim (2003). Strategic Human Resource Development. SAGE. p. 18. ISBN 9781412932288.

- Taska, Lucy; Barnes, Alison (2012). Rethinking Misbehavior and Resistance in Organizations. Emerald Group Publishing. p. 15. ISBN 9781780526621.

- Head, Simon (23 February 2014). "Worse than Wal-Mart: Amazon's sick brutality and secret history of ruthlessly intimidating workers". Salon.

- Head, Simon (2014). "Walmart and Amazon". In Tim Bartlett (ed.). Mindless: Why Smarter Machines Makes Dumber Humans. Basic Books. ISBN 9780465018444.

- Romele, Alberto; Emmenegger, Camilla; Gallino, Francesco; Gorgone, Daniel (2015). Peres, Paula; Mesquita, Anabela (eds.). Technologies of Voluntary Servitude (TovS): A Post-Foucauldian Perspective on Social media. ECSM2015-Proceedings of the 2nd European Conference on Social Media 2015: ECSM 2015. Academic Conferences Limited. pp. 377–378. ISBN 9781910810316.

- Donald Preziosi (1989). Rethinking Art History: Meditations on a Coy Science. Yale University Press. p. 66. ISBN 9780300049831.

- Luigi Vessella (2017). Open Prison Architecture: Design Criteria for a New Prison Typology. WITPress. p. 10. ISBN 9781784662479.

- Nicholas Mirzoeff (2002). The Visual Culture Reader. Psychology Press. p. 403. ISBN 9780415252225.

- Edward Ziter (2003). The Orient on the Victorian Stage. Cambridge University Press. p. 119. ISBN 9780521818292.

- Heather Glen (2002). Charlotte Brontë: The Imagination in History. Oxford University Press. pp. 213. ISBN 9780198187615.

- Edward Ziter (2003). The Orient on the Victorian Stage. Cambridge University Press. p. 119. ISBN 9780521818292.

- Rose Harris-Birtill (2019). David Mitchell's Post-Secular World: Buddhism, Belief and the Urgency of Compassion. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 120. ISBN 9781350078604.

- Doctor Who, The Deadly Assassin, Season 14, Serial 3; November 1976

- Stephen Hart (2013). Gabriel García Márquez. Reaktion Books. p. 121. ISBN 9781780232423.

- Scott Dimovitz (2016). Angela Carter: Surrealist, Psychologist, Moral Pornographer. Routledge. p. 165. ISBN 9781317181125.

- Dimitris Akrivos & Alexandros K. Antoniou (2019). Crime, Deviance and Popular Culture: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives. Springer. p. 77–78. ISBN 9783030049126.