Prehistoric North Africa

The Prehistory of North Africa spans the period of earliest human presence in the region to gradual onset of historicity in the Maghreb (Tamazgha) during classical antiquity.

.svg.png.webp)

Early anatomically modern humans are known to have been present at Jebel Irhoud, in what is now Morocco, from about 300,000 years ago.[2] The Nile valley (Ancient Egypt) participated in the development of the Old World Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age, along with the Ancient Near East. By contrast, the Maghreb, including the "Green Sahara", remained in the Mesolithic stage until the 4th millennium BC, with gradual introduction of the Neolithic nomadic pastoralism in the 3rd millennium BC, and early Iron Age Phoenician colonization along the Mediterranean coast from about 1100 BC.

Saharan climate and human migration

Human habitation in North Africa has been greatly influenced by the climate of the Sahara (currently the world's largest warm desert), which has undergone enormous variations between wet and dry over the last few hundred thousand years.[3] This is due to a 41000-year Axial tilt cycle in which the tilt of the earth changes between 22° and 24.5°.[4] At present (2000 AD), we are in a dry period, but it is expected that the Sahara will become green again in 15000 years (17000 AD).

During the last glacial period, the Sahara was much larger than it is today, extending south beyond its current boundaries.[5] The end of the glacial period brought more rain to the Sahara, from about 8000 BC to 6000 BC, perhaps because of low pressure areas over the collapsing ice sheets to the north.[6] Once the ice sheets were gone, the northern Sahara dried out. In the southern Sahara, the drying trend was initially counteracted by the monsoon, which brought rain further north than it does today. By around 4200 BC, however, the monsoon retreated south to approximately where it is today,[7] leading to the gradual desertification of the Sahara.[8] The Sahara is now as dry as it was about 13,000 years ago.[3]

These conditions are responsible for what has been called the Sahara pump theory. During periods of a wet or "Green Sahara", the Sahara becomes a savanna grassland and various flora and fauna become more common. Following inter-pluvial arid periods, the Sahara area then reverts to desert conditions and the flora and fauna are forced to retreat northwards to the Atlas Mountains, southwards into West Africa, or eastwards into the Nile Valley. This separates populations of some of the species in areas with different climates, forcing them to adapt, possibly giving rise to allopatric speciation.

In terms of human evolution, the Saharan pump has been used to date four waves of human migration from Africa, namely:[9]

- Homo erectus (ssp. ergaster) into Southeast and East Asia

- Homo heidelbergensis into the Middle East and Western Europe

- Homo sapiens sapiens "Out of Africa theory"

- The spread of Afro-Asiatic languages (Berber and Egyptian to North Africa and Semitic to the Arabian Peninsula and Middle East).

Early and middle Paleolithic

The earliest inhabitants of central North Africa have left behind significant remains: early remnants of hominid occupation in North Africa, for example, were found in Ain el Hanech, in Setif (c. 200,000 BCE); in fact, more recent investigations have found signs of Oldowan technology there, and indicate a date of up to 1.8 million BC.[11] Some studies have placed the earliest settlement of homo sapiens in North Africa to around 160,000 years ago.[12] According to some sources, North Africa was the site of the highest state of development of Middle Paleolithic flake-tool techniques. Tools of this era, starting about 130,000 BCE, are called Aterian(after the site Bir el Ater, south of Annaba) and are marked by a high standard of workmanship, great variety, and specialization.

Humans in North Africa (Nazlet Sabaha, Egypt) are known to have dabbled in chert mining, as early as ~100,000 years ago, likely for use as tools.[13][14]

Late Paleolithic and Mesolithic

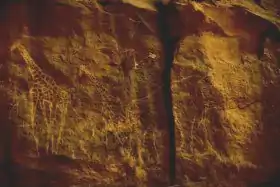

The earliest blade industries in North Africa belong to the Iberomaurusian or Oranian (after a site near Oran). This lithic industry appears to have spread throughout the coastal regions of North Africa between 15,000 and 10,000 BC. Between about 9000 and 5000 BC, the Capsian culture made its appearance showing signs to belong to the Neolithic and began influencing the Iberomaurusian, and after about 3000 BC the remains of just one human culture can be found throughout the former region. Neolithic society (marked by animal domestication and subsistence agriculture) spread in the Saharan and Mediterranean North Africa after the Levant between 6000 and 2000 BC. This type of economy, so richly depicted in the Tassili n'Ajjer cave paintings, predominated in North Africa until the classical period.

Saharan rock art was produced in the "Green Sahara" during the Neolithic Subpluvial period (about 8000 to 4000 BC). They were executed by hunter-gatherers of the Capsian period who lived in a savanna region teeming with giant buffalo, elephant, rhinoceros, and hippopotamus.

The Mesolithic cultures producing rock art (notably that at Tassili n'Ajjer in southeastern Algeria) flourished during the Neolithic Subpluvial.

Neolithic

Equitable conditions during the Neolithic Subpluvial supported increased human settlement of the Nile Valley in Egypt, as well as neolithic societies in Sudan and throughout the present-day Sahara. Cultures producing rock art (notably that at Tassili n'Ajjer in southeastern Algeria) flourished during this period.

The practical consequences of these changes took the form of increased abundance of fish, waterfowl, freshwater molluscs, rodents, hippopotamus and crocodiles. The riches of this increased aquatic biomass were exploited by humans with rafts, boats, weirs, traps, harpoons, nets, hooks, lines and sinkers. This "riparian" (river) way of life supported much larger communities than could that of typical hunting bands.[15] These changes, along with the local development of pottery (whereby liquids could be both stored and heated) resulted in a "culinary revolution" consisting of soup, fish stew and porridge.[16] The last mentioned implies the cooking of gathered cereals.

The classic account of the riparian lifestyle of this period comes from investigations in Sudan during World War II by British archeologist Anthony Arkell.[17] Arkell's report described a Late Stone Age settlement on a sandbank of the Blue Nile which was then about 12 feet (3.7 m) higher than its present flood stage. The countryside was clearly savanna, not the present-day desert, as evidenced by the bones of the most common species found in the middens — antelope, which require large expanses of seed-bearing grasses. These people probably lived mainly on fish, however, and Arkell concluded, based on the totality of the evidence, that rainfall at the time was at least three times that of today. The physical characteristics derived from skeletal remains suggested that these people were related to modern Nilotic peoples, such as the Nuer and Dinka. Subsequent radiocarbon dating firmly established Arkell's site to between 7000 and 5000 BCE. Based on common patterns at his site and at French-excavated sites already reported from Chad, Mali and Niger (e.g., bone harpoons and a characteristic "wavy line" pottery), Arkell inferred "a common fishing and hunting culture spread by negroid people right across Africa at about the latitude of Khartoum at a time when the climate was so different that it was not desert." The originators of the wavy line pottery are as yet unidentified.

In the 1960s, the archeologist Gabriel Camps investigated the remains of a hunting and fishing community dating from about 6700 BCE in southern Algeria. These pottery-making people (the "wavy line" motif again) were black African rather than Mediterranean in origin and (according to Camps) evidenced definite signs of deliberate cultivation of grain crops as opposed to simply the gathering of wild grains.[18] Later studies at the site have shown the culture to be hunter-gatherers and not agriculturalists, as all the grains were morphologically wild, and the society was not sedentary.

Human remains were found by archaeologists in 2000 at a site known as Gobero in the Ténéré Desert of northeastern Niger.[19][20] The Gobero finds represent a uniquely preserved record of human habitation and burials from what is now called the Kiffian (7700–6200 BCE) and the Tenerian (5200–2500 BCE) cultures.[19]

Dotted wavy line pottery and fishing cultures have also been located in the Lake Turkana region in poorly dated contexts.[21] By 3000 BCE, it does not appear that the Turkana Basin was populated with harpoon and dotted wavy line pottery users, but fishing remained an important part of peoples' diets into the late Holocene.[21]

Bronze Age to Iron Age

The beginning of the Bronze Age in Egypt is conventionally identified as the Protodynastic Period, following the Neolithic Naqada culture about 3200 BC. The Egyptian Bronze Age corresponds to the Old, Middle and New Kingdoms. The Iron Age in Egypt corresponds to the Third Intermediate Period of Egypt.

While the Nile valley (Egypt and Meroë) had entered historicity since the Bronze Age, Tamazgha (Maghreb) remained in the prehistoric period longer. Mesolithic hunter-gatherers are gradually replaced by pastoralists (nomads) by the early 3rd millennium BC. Some Phoenician and Greek colonies were established along the Mediterranean coast during the 7th century BC.

Notes

- According to UN country classification here: http://millenniumindicators.un.org/unsd/methods/m49/m49regin.htm%5B%5D The disputed territory of Western Sahara (formerly Spanish Sahara) is mostly administered by Morocco; the Polisario Front claims the territory in militating for the establishment of an independent republic, and exercises limited control over rump border territories.

- Callaway, Ewen (7 June 2017). "Oldest Homo sapiens fossil claim rewrites our species' history". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2017.22114.

- White, Kevin; Mattingly, David J. (2006). "Ancient Lakes of the Sahara". American Scientist. 94 (1): 58–65. doi:10.1511/2006.57.983.

- Berger, André (1976). "Obliquity and precession for the last 5000000 years". Astronomy & Astrophysics : A European Journal. 51 (1): 127–135. Bibcode:1976A&A....51..127B. hdl:2078.1/66678.

- Ehret, Christopher (2002). The Civilizations of Africa: A History to 1800. University Press of Virginia. ISBN 978-0-8139-2085-6.

- Fezzan Project — Palaeoclimate and environment. Retrieved March 15, 2006. Archived June 7, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "Sahara's Abrupt Desertification Started By Changes In Earth's Orbit, Accelerated By Atmospheric And Vegetation Feedbacks". ScienceDaily.

- Kröpelin, S.; Verschuren, D.; Lezine, A.- M.; Eggermont, H.; Cocquyt, C.; Francus, P.; Cazet, J.- P.; Fagot, M.; Rumes, B.; Russell, J. M.; Darius, F.; Conley, D. J.; Schuster, M.; von Suchodoletz, H.; Engstrom, D. R. (9 May 2008). "Climate-Driven Ecosystem Succession in the Sahara: The Past 6000 Years" (PDF). Science. 320 (5877): 765–768. doi:10.1126/science.1154913. PMID 18467583. S2CID 9045667.

- Stephen, Stokes. "Chronology, Adaptation and Environment of the Middle Palaeolithic in Northern Africa". Human Evolution, Cambridge University. Archived from the original on 2012-03-20. Retrieved 2014-01-04.

- http://www.geneawiki.com/index.php/Alg%C3%A9rie_-_Roknia%5B%5D%5B%5D

- Sahnouni, Mohamed; de Heinzelin, Jean (November 1998). "The Site of Ain Hanech Revisited: New Investigations at this Lower Pleistocene Site in Northern Algeria" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science. 25 (11): 1083–1101. doi:10.1006/jasc.1998.0278. S2CID 129518072.

- Smith, Tanya M.; Tafforeau, Paul; Reid, Donald J.; Grün, Rainer; Eggins, Stephen; Boutakiout, Mohamed; Hublin, Jean-Jacques (10 April 2007). "Earliest evidence of modern human life history in North African early Homo sapiens". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (15): 6128–6133. doi:10.1073/pnas.0700747104. PMC 1828706. PMID 17372199.

- Dionne, Yvan (19 August 2014). "5 Oldest Mines in the World: A Casual Survey". Archived from the original on 2019-01-05. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- Guinness World Records (2015). "Mine craft". Guinness World Records 2016. Macmillan. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-910561-06-5.

- Oliver, Roland (2018) [2000]. "The Fruits of the Earth". The African Experience: From Olduvai Gorge to the 21st Century (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge. p. 37. doi:10.4324/9780429496875-3. ISBN 9780429496875.

- Sutton, J. E. G. (22 January 2009). "The Aquatic Civilization of Middle Africa". The Journal of African History. 15 (4): 527–546. doi:10.1017/s0021853700013864.

- Arkell, A. J (1949). Early Khartoum: an account of the excavation of an early occupation site. Oxford University Press. OCLC 600772099.

- Camps, Gabriel (1974). Les civilisations préhistoriques de l'Afrique du Nord et du Sahara [The prehistoric civilizations of North Africa and the Sahara] (in French). Doin. pp. 22, 225–226. ISBN 978-2-7040-0030-2.

- Sereno, Paul C.; Garcea, Elena A. A.; Jousse, Hélène; Stojanowski, Christopher M.; Saliège, Jean-François; Maga, Abdoulaye; Ide, Oumarou A.; Knudson, Kelly J.; Mercuri, Anna Maria; Stafford, Thomas W.; Kaye, Thomas G.; Giraudi, Carlo; N'siala, Isabella Massamba; Cocca, Enzo; Moots, Hannah M.; Dutheil, Didier B.; Stivers, Jeffrey P. (14 August 2008). "Lakeside Cemeteries in the Sahara: 5000 Years of Holocene Population and Environmental Change". PLOS ONE. 3 (8): e2995. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002995. PMC 2515196. PMID 18701936. Lay summary.

- Gwin, Peter (1 September 2011). "Lost Lords of the Sahara". National Geographic.

- Wright, David K.; Forman, Steven L.; Kiura, Purity; Bloszies, Christopher; Beyin, Amanuel (27 June 2015). "Lakeside View: Sociocultural Responses to Changing Water Levels of Lake Turkana, Kenya". African Archaeological Review. 32 (2): 335–367. doi:10.1007/s10437-015-9185-8.

References

- Original text: Library of Congress Country Study of Algeria

- AFRICA DURING THE LAST 150,000 YEARS (climate) from ORNL