History of architecture

The history of architecture traces the changes in architecture through various traditions, regions, overarching stylistic trends, and dates. The beginnings of all these traditions is thought to be humans satisfying the very basic need of shelter and protection.[1] The term "architecture" generally refers to buildings, but in its essence is much broader, including fields we now consider specialized forms of practice, such as civil engineering, naval, military,[2] and landscape architecture.

Neolithic

Neolithic architecture is the architecture of the Neolithic period. Although many dwellings belonging to all prehistoric periods and also some clay models of dwellings have been uncovered enabling the creation of faithful reconstructions, they seldom included elements that may relate them to art. Some exceptions are provided by wall decorations and by finds that equally apply to Neolithic and Chalcolithic rites and art.

In South and Southwest Asia, Neolithic cultures appear soon after 10,000 BC, initially in the Levant (Pre-Pottery Neolithic A and Pre-Pottery Neolithic B) and from there spread eastwards and westwards. There are early Neolithic cultures in Southeast Anatolia, Syria and Iraq by 8000 BC, and food-producing societies first appear in southeast Europe by 7000 BC, and Central Europe by c. 5500 BC (of which the earliest cultural complexes include the Starčevo-Koros (Cris), Linearbandkeramic, and Vinča).[3][4][5][6]

Neolithic settlements and "cities" include:

- Göbekli Tepe in Turkey, ca. 9,000 BC

- Jericho in the Levant, Neolithic from around 8,350 BC, arising from the earlier Epipaleolithic Natufian culture

- Nevali Cori in Turkey, ca. 8,000 BC

- Çatalhöyük in Turkey, 7,500 BC

- Mehrgarh in Pakistan, 7,000 BC

- Knap of Howar and Skara Brae, the Orkney Islands, Scotland, from 3,500 BC

- over 3,000 settlements of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture, some with populations up to 15,000 residents, flourished in present-day Romania, Moldova and Ukraine from 5,400 to 2,800 BC.

The Neolithic people in the Levant, Anatolia, Syria, northern Mesopotamia and Central Asia were great builders, utilizing mud-brick to construct houses and villages. At Çatalhöyük, houses were plastered and painted with elaborate scenes of humans and animals. The Mediterranean Neolithic cultures of Malta worshiped in megalithic temples.

In Europe, long houses built from wattle and daub were constructed. Elaborate tombs for the dead were also built. These tombs are particularly numerous in Ireland, where there are many thousands still in existence. Neolithic people in the British Isles built long barrows and chamber tombs for their dead and causewayed camps, henges flint mines and cursus monuments.

Göbekli Tepe in Turkey, founded in 10th millennium BC and abandoned in 8th millennium BC

Göbekli Tepe in Turkey, founded in 10th millennium BC and abandoned in 8th millennium BC Pottery miniature of a Cucuteni-Trypillian house

Pottery miniature of a Cucuteni-Trypillian house Miniature of a regular Cucuteni-Trypillian house, full of ceramic vessels

Miniature of a regular Cucuteni-Trypillian house, full of ceramic vessels

Antiquity

Ancient Mesopotamia

Ancient Mesopotamia is most noted for its construction of mud brick buildings and the construction of ziggurats, occupying a prominent place in each city and consisting of an artificial mound, often rising in huge steps, surmounted by a temple. The mound was no doubt to elevate the temple to a commanding position in what was otherwise a flat river valley. The great city of Uruk had a number of religious precincts, containing many temples larger and more ambitious than any buildings previously known.[7]

The word ziggurat is an anglicized form of the Akkadian word ziqqurratum, the name given to the solid stepped towers of mud brick. It derives from the verb zaqaru, ("to be high"). The buildings are described as being like mountains linking Earth and heaven. The Ziggurat of Ur, excavated by Leonard Woolley, is 64 by 46 meters at base and originally some 12 meters in height with three stories. It was built under Ur-Nammu (circa 2100 B.C.) and rebuilt under Nabonidus (555–539 B.C.), when it was increased in height to probably seven stories.[8]

Assyrian palaces had a large public court with a suite of apartments on the east side and a series of large banqueting halls on the south side. This was to become the traditional plan of Assyrian palaces, built and adorned for the glorification of the king.[9] Massive amounts of ivory furniture pieces were found in some palaces.

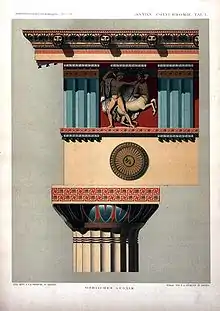

Illustration of a hall in the Assyrian Palace of Ashurnasrirpal II by Austen Henry Layard (1854)

Illustration of a hall in the Assyrian Palace of Ashurnasrirpal II by Austen Henry Layard (1854)

Assyrian reliefs from the Palace of Sargon II in Khorsabad, 721-705 BC, Oriental Institute Museum (Chicago, USA)

Assyrian reliefs from the Palace of Sargon II in Khorsabad, 721-705 BC, Oriental Institute Museum (Chicago, USA)

Ancient Egyptian

In Ancient Egypt and other early societies, people believed in the omnipotence of gods, with many aspects of daily life carried out with respect to the idea of the divine or supernatural and the way it was manifest in the mortal cycles of generations, years, seasons, days and nights. Harvests for example were seen as the benevolence of fertility deities. Thus, the founding and ordering of the city and her most important buildings (the palace and temple) were often executed by priests or even the ruler himself and the construction was accompanied by rituals intended to enter human activity into continued divine benediction.

Ancient architecture is characterized by this tension between the divine and mortal world. Cities would mark a contained sacred space over the wilderness of nature outside, and the temple or palace continued this order by acting as a house for the gods. The architect, be he priest or king, was not the sole important figure, he was merely part of a continuing tradition.

Pair of obelisks of Nebsen; 2323-2100 BC; limestone; (the one from left) height: 52.7 cm, (the one from right) height: 51.1 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Pair of obelisks of Nebsen; 2323-2100 BC; limestone; (the one from left) height: 52.7 cm, (the one from right) height: 51.1 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City) Model of a house; 1750-1700 BC; pottery; 27 x 27 x 17 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Model of a house; 1750-1700 BC; pottery; 27 x 27 x 17 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art Ceiling painting from the palace of Amenhotep III; circa 1390–1353 BC; dried mud, mud plaster and paint Gesso; 140 x 140 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Ceiling painting from the palace of Amenhotep III; circa 1390–1353 BC; dried mud, mud plaster and paint Gesso; 140 x 140 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art Window grill from a palace of Ramesses III; 1184-1153 BC; painted sandstone; height: 103.5 cm, width: 102.9 cm, depth: 14.6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

Window grill from a palace of Ramesses III; 1184-1153 BC; painted sandstone; height: 103.5 cm, width: 102.9 cm, depth: 14.6 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art Column with Hathor-emblem capital and names of Nectanebo I on the shaft; 380–362 BC; limestone; height: 102 cm, width: 34.3 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art

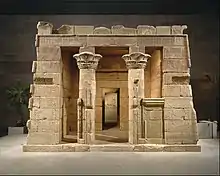

Column with Hathor-emblem capital and names of Nectanebo I on the shaft; 380–362 BC; limestone; height: 102 cm, width: 34.3 cm; Metropolitan Museum of Art The Temple of Dendur; completed by 10 BC; aeolian sandstone; temple proper: height: 6.4 m, width: 6.4 m; length: 12.5 m; Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Temple of Dendur; completed by 10 BC; aeolian sandstone; temple proper: height: 6.4 m, width: 6.4 m; length: 12.5 m; Metropolitan Museum of Art A view of the pyramids at Giza. From left to right, the three largest are: the Pyramid of Menkaure, the Pyramid of Khafre and the Great Pyramid of Khufu

A view of the pyramids at Giza. From left to right, the three largest are: the Pyramid of Menkaure, the Pyramid of Khafre and the Great Pyramid of Khufu The well preserved The Temple of Isis from Philae (Egypt) is an example of Egyptian architecture and architectural sculpture

The well preserved The Temple of Isis from Philae (Egypt) is an example of Egyptian architecture and architectural sculpture The Great Temple of Ramesses II from Abu Simbel, founded in circa 1264 BC, in the Aswan Governorate (Egypt)

The Great Temple of Ramesses II from Abu Simbel, founded in circa 1264 BC, in the Aswan Governorate (Egypt) Relief from the Dendera Temple complex (Egypt)

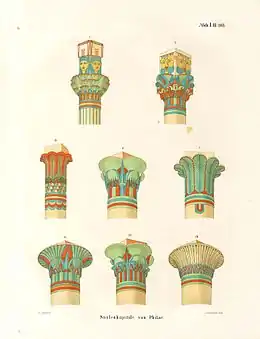

Relief from the Dendera Temple complex (Egypt) Illustrations of various types of capitals, drawn by the egyptologist Karl Richard Lepsius

Illustrations of various types of capitals, drawn by the egyptologist Karl Richard Lepsius._Memnonia_(Ramesseum)-_S%C3%A4ulen_aus_der_Halle_des_Tempels_Ramses_II_(NYPL_b14291191-37596).jpg.webp) Illustrations with two types of columns from the hall of the Ramses II Temple, drawn in 1849

Illustrations with two types of columns from the hall of the Ramses II Temple, drawn in 1849

Pre-classical

The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age Aegean civilization on the island of Crete and other Aegean Islands, flourishing from circa 2700 to circa 1450 BC until a late period of decline, finally ending around 1100 BC. Minoan buildings often had flat, tiled roofs; plaster, wood or flagstone floors, and stood two to three stories high. Lower walls were typically constructed of stone and rubble, and the upper walls of mudbrick. Ceiling timbers held up the roofs. The main colors used in Minoan frescos were black (carbonaceous shale), white (hydrate of lime), red (hematite), yellow (ochre), blue (silicate of cooper) and green (yellow and blue mixed together). The most iconic Minoan building is the Palace of Knossos, being connected to the mythological story of The Bull of Minos, since it is in this palace where it was written that the labyrinth existed.

A common characteristic of the Minoan architecture were flat roofs. The rooms of villas didn't have windows to the streets, the light arriving from courtyards. In the 2nd millennium BC, the villas had one or two floors, and the palaces even three. One of the most notable Minoan contributions to architecture is their inverted column, wider at the top than the base (unlike most Greek columns, which are wider at the bottom to give an impression of height). The columns were made of wood (not stone) and were generally painted red. Mounted on a simple stone base, they were topped with a pillow-like, round capital.[10][11]

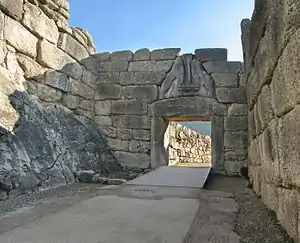

Aegean art reached its peak in circa 1650-1450 BC and was at first dominated by the Minoans. However, at the height of its influence, the Minoan civilization fell and its position was quickly inherited by the Mycenaeans, a race of warriors who flourished in Greece from 1600 to 1200 BC. Although Cretan artisans may have been employed on the reworking of Mycenaean citadels, the two styles remained distinct. Mycenaean buildings were carefully planned and focused on the megaron (central unit), while the Minoans favoured complex, labyrinthine forms.[12] Mycenaean columns, like the Minoan examples, were slender and tapered sharply downwords.[13]

.jpg.webp) Queen's Megaron from the Palace of Knossos, with the Dolphin fresco. A common characteristic of Minoan palaces were frescos.

Queen's Megaron from the Palace of Knossos, with the Dolphin fresco. A common characteristic of Minoan palaces were frescos. Minoan town house model, circa 1700–1675 BC, terracotta, height: 18 cm, from Archanes (Crete), in Archaeological Museum of Heraklion (Heraklion, Greece)[14]

Minoan town house model, circa 1700–1675 BC, terracotta, height: 18 cm, from Archanes (Crete), in Archaeological Museum of Heraklion (Heraklion, Greece)[14] Illustration of the end of a Mycenaean column, from the Tomb of Agamemnon

Illustration of the end of a Mycenaean column, from the Tomb of Agamemnon A preserved part of a large mural composition from the Palace of Thebes, circa 14th-13th BC

A preserved part of a large mural composition from the Palace of Thebes, circa 14th-13th BC

Classical and Hellenistic

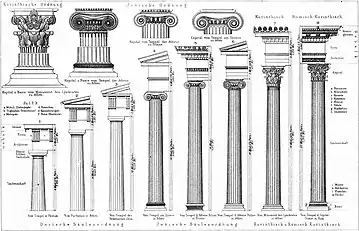

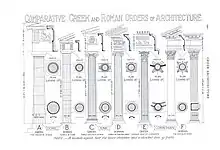

The architecture and urbanism of the Greeks and Romans was very different from that of the Egyptians and Persians. Civic life gained importance for all members of the community. In the time of the ancients religious matters were only handled by the ruling class; by the time of the Greeks, religious mystery had skipped the confines of the temple-palace compounds and was the subject of the people or polis. Ancient Greek architecture was fundamentally a representation of timber post and lintel, or "trabeated" construction in stone, and most surviving buildings are temples. Rows of tall columns supported a lintel, which in turn supported a pitched roof structure running the length of the building. The triangular gable formed at either end of the pitched roof was often heavily decorated and was a key feature of the style. Today we think of Classical and Hellenist Greek architecture as being characterized by the use of plain white marble, but originally it would have been brightly painted in gaudy colors. For example, Doric order capitals were painted with geometric and leaf patterns.[15]

Greek civic life was sustained by new, open spaces called the agora, which were surrounded by public buildings, stores and temples. The agora embodied the newfound respect for social justice received through open debate rather than imperial mandate. Though divine wisdom still presided over human affairs, the living rituals of ancient civilizations had become inscribed in space, in the paths that wound towards the acropolis for example. Each place had its own nature, set within a world refracted through myth, thus temples were sited atop mountains all the better to touch the heavens.

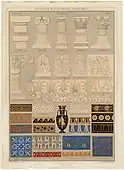

Greek architecture was typically made of stone. Most surviving buildings are temples, based on strict rules of proportion. These temples typically included a peristyle (outer area with (typically Doric) columns), and three-sections in the middle, being 1. the pronaus (entrance), 2. the main cella or naos chamber (where a statue of the god or goddess and an altar was built), and 3. the opisthodomos behind the cella.[16] The most iconic element of Hellenistic architecture is of course the column. The Doric order, sober and severe, was dominant in Peloponnese and Magna Graecia (Sicily and South Italy), being named the masculine order of Hellenistic architecture. Meanwhile, the Ionic order is graceful and more ornamented, being the feminine order. Because of Ionic's proportions, it is used especially for monumental buildings. The third of the Greek orders was also the last to be developed. The earliest documented examples of the use of the Corinthian order are (internally) at the Temple of Apollo Epicurius, Bassae (429-390 BC) and (externally) at the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates (335-334 BC). Corinthian was not, like the Doric and Ionic orders, a structural system. It was purely decorative, its effect due almost wholly to its elaborate floral capital. This, according to Vitruvius, was designed by the Athenian sculptor Callimachus, and may originally have been worked in bronze. Apart from this capital, all the constituent parts were borrowed from the Ionic order. Gradually, in Hellenistic times (after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC), Corinthian did begin to develop, but it was left to the Romans to blend the elements together and make it perfect.[17]

.jpg.webp) Doric: The Parthenon on the Athenian Acropolis, built of marble and limestone between circa 460-406 BC, dedicated to the goddess Athena[18]

Doric: The Parthenon on the Athenian Acropolis, built of marble and limestone between circa 460-406 BC, dedicated to the goddess Athena[18] Page with illustration of the Doric order, made by Vincenzo Scamozzi in 1697

Page with illustration of the Doric order, made by Vincenzo Scamozzi in 1697 Engraving of a Doric entablature, from 1536, by Agostino Veneziano, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Engraving of a Doric entablature, from 1536, by Agostino Veneziano, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City) Ionic: The Temple of Athena Nike on the Athenian Acropolis, dedicated to the goddess Athena, built between circa 437 BC and 432 BC[19]

Ionic: The Temple of Athena Nike on the Athenian Acropolis, dedicated to the goddess Athena, built between circa 437 BC and 432 BC[19] Page with illustration of the Ionic order, made by Vincenzo Scamozzi in 1697

Page with illustration of the Ionic order, made by Vincenzo Scamozzi in 1697 Engraving of an Ionic entablature, from 1528, by Agostino Veneziano, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Engraving of an Ionic entablature, from 1528, by Agostino Veneziano, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art_(30776483926).jpg.webp) Corinthian: The Temple of Olympian Zeus in Athens, started in the 6th century BC and finished in the 2nd century AD

Corinthian: The Temple of Olympian Zeus in Athens, started in the 6th century BC and finished in the 2nd century AD Page with illustration of the Corinthian order, made by Vincenzo Scamozzi in 1697

Page with illustration of the Corinthian order, made by Vincenzo Scamozzi in 1697 Engraving of a Corinthian entablature, from 1528, by Agostino Veneziano, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Engraving of a Corinthian entablature, from 1528, by Agostino Veneziano, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.jpg.webp) Caryatids of the Erechtheion from the Athenian Acropolis, exhibited in the Acropolis Museum, (Athens)

Caryatids of the Erechtheion from the Athenian Acropolis, exhibited in the Acropolis Museum, (Athens) Illustration of the altar and statue of the Temple of Asclepius (Epidaurus, Greece), which shows the interior of an Ancient Greek temple

Illustration of the altar and statue of the Temple of Asclepius (Epidaurus, Greece), which shows the interior of an Ancient Greek temple

The reconstructed façade of the Nereid Monument, in the British Museum (London)

The reconstructed façade of the Nereid Monument, in the British Museum (London) The mosaic floor of a house at Delos

The mosaic floor of a house at Delos Illustrations of examples of ancient Greek ornaments and patterns, drawn in 1874

Illustrations of examples of ancient Greek ornaments and patterns, drawn in 1874

Etruscan

Just as Mycenaean architecture seems to have influenced the classical Greeks, so the structures raised by the Etruscans are important in the evolution of ancient Roman architecture. The Etruscans probably originated in Asia Minor and settled in west-central Italy (Etruria), between the rivers Arno and Tiber. From the late 7th century BC their power grew, and for a while Rome itself was ruled by Etruscan kings. But with the establishment of a republic in 509 BC, Etruscan civilization began to decline and its various city states were conquered. Nonetheless, the Etruscans did not cease their architectural activity, which retained its distinct character until the 1st century BC. Few buildings survived, but those that do are extremely fine, especially the tombs, which were located mainly in specific necropolis sites.[20]

The Etruscans, as we know from the writings of Vitruvius, a Roman architect and engineer of the 1st century BC, developed a style of temple building which, though inspired by Greek and Oriental examples, was quite distinctive in its own right. It conformed to specific rules, referred to as tuscanicae dispositiones by Vitruvius. Temples were usually of mud-brick and timber, though stone was used later, and seem to have been built to face south. They were placed at the centre of towns and fronted on to squares, in which altars were placed.[21] Temples were lavishly decorated with painted terracotta, which served partly to protect the wooden elements of the structure. For example, the sides of the roof bore ante-fixae (slabs used to close the end of a row of tiles), and there were statues over the pediment and within the pronaos.[22] Many of the temples were divided into three cellas (sanctuaries), the central one being the most important and sometimes the largest.[21]

.jpg.webp) Model of a temple, constructed between 1889 and 1890 on the basis of the ruins found in Alatri, now in National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia (Rome)

Model of a temple, constructed between 1889 and 1890 on the basis of the ruins found in Alatri, now in National Etruscan Museum of Villa Giulia (Rome)

.JPG.webp) Silenus-head antefix, made in the 5th century BC, in Museo nazionale dell'Agro Falisco (Civita Castellana, Lazio, Italy)

Silenus-head antefix, made in the 5th century BC, in Museo nazionale dell'Agro Falisco (Civita Castellana, Lazio, Italy) Detail of the Etruscan temple reconstruction at the Villa Giulia in Rome

Detail of the Etruscan temple reconstruction at the Villa Giulia in Rome

Roman

_from_the_Villa_of_P._Fannius_Synistor_at_Boscoreale_MET_DP143704.jpg.webp)

The Romans conquered the Greek cities in Italy around three hundred years BCE and much of the Western world after that. The Roman problem of rulership involved the unity of disparity – from Spanish to Greek, Macedonian to Carthaginian – Roman rule had extended itself across the breadth of the known world and the myriad pacified cultures forming this ecumene presented a new challenge for justice. Roman architecture, especially Roman temple architecture, shared many basic characteristics with Greek temple architecture, including the prominent portico, use of the Classical orders (mainly Corinthian and Composite), and the stepped podium. However, it tended to be more ornate and elaborate overall.[23]

The Corinthian order was the most widely used order in Roman architecture. It differed from the Greek Corinthian in its more ornate entablature and capital, but more particularly in the introduction of modillions (horizontal consoles that supported a deeper cornice). Sometimes coffering was introduced between these to create a greater impression from the ground.[24] Early Roman Corinthian capitals tended to be squatter than later examples, with fleshier acanthus leaves and larger flowers on the abacus.[25]

One way to look at the unity of Roman architecture is through a new-found realization of theory derived from practice, and embodied spatially. Civically, we find this happening in the Roman forum (sibling of the Greek agora), where public participation is increasingly removed from the concrete performance of rituals and represented in the decor of the architecture. Thus, we finally see the beginnings of the contemporary public square in the Forum Iulium, begun by Julius Caesar, where the buildings present themselves through their facades as representations within the space.

As the Romans chose representations of sanctity over actual sacred spaces to participate in society, the communicative nature of space was opened to human manipulation. None of which would have been possible without the advances of Roman engineering and construction or the newly found marble quarries, which were the spoils of war; inventions like the arch and concrete gave a whole new form to Roman architecture, fluidly enclosing space in taut domes and colonnades, clothing the grounds for imperial rulership and civic order. This was also a response to the changing social climate which demanded new buildings of increasing complexity: the Colosseum, the residential block, bigger hospitals and academies. General civil construction such as roads and bridges began to be built.

The Romans widely employed, and further developed, the arch, vault and dome, all of which were little used before, particularly in Europe.[26] Their innovative use of Roman concrete facilitated the building of the many public buildings of often unprecedented size throughout the Roman empire. These include temples, thermae, bridges, aqueducts, harbours, triumphal arches, amphitheatres, circuses palaces, mausolea and in the late empire also churches. Two widely used motifs were the bucranium (ox skulls) and the festoon (a wreath or hanging from two points).

Roman domes permitted construction of vaulted ceilings and enabled huge covered public spaces such as the public baths like Baths of Diocletian or the monumental Pantheon in the city of Rome.

Art historians such as Gottfried Richter in the 1920s identified the Roman architectural innovation as being the triumphal arch and it is poignant to see how this symbol of power on earth was transformed and utilized within the Christian basilicas when the Roman Empire of the West was on its last legs: The arch was set before the altar to symbolize the triumph of Christ and the after life. It is in their impressive aqueducts that we see the arch triumphant, especially in the many surviving examples, such as the Pont du Gard, the Aqueduct of Segovia, and the remains of the Aqueducts of Rome itself. Their survival is testimony to the durability of their materials and design.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp) The Corinthian capital: Detail from the Parthenon (Rome)

The Corinthian capital: Detail from the Parthenon (Rome).JPG.webp)

The Arch: The Colosseum, the most iconic Roman building

The Arch: The Colosseum, the most iconic Roman building The Dome: Interior of the Pantheon from Rome

The Dome: Interior of the Pantheon from Rome

The Roman bricks: Close-up view of the wall of the Roman shore fort at Burgh Castle (England)

The Roman bricks: Close-up view of the wall of the Roman shore fort at Burgh Castle (England)_from_the_Villa_of_P._Fannius_Synistor_at_Boscoreale_MET_DP170950.jpg.webp) The Frescos: Cubiculum (bedroom) from the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

The Frescos: Cubiculum (bedroom) from the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Persian

The pre-Islamic styles draw on 3-4 thousand years of architectural development from various civilizations of the Iranian plateau. The Islamic architecture of Iran in turn, draws ideas from its pre-Islamic predecessor, and has geometrical and repetitive forms, as well as surfaces that are richly decorated with glazed tiles, carved stucco, patterned brickwork, floral motifs, and calligraphy. Iran is recognized by UNESCO as being one of the cradles of civilization.[28]

Each of the periods of Elamites, Achaemenids, Parthians, and Sassanids were creators of great architecture that over the ages has spread wide and far to other cultures being adopted. Although Iran has suffered its share of destruction, including Alexander The Great's decision to burn Persepolis, there are sufficient remains to form a picture of its classical architecture.

The Achaemenids built on a grand scale. The artists and materials they used were brought in from practically all territories of what was then the largest state in the world. Pasargadae set the standard: its city was laid out in an extensive park with bridges, gardens, colonnaded palaces and open column pavilions. Pasargadae along with Susa and Persepolis expressed the authority of The King of Kings, the staircases of the latter recording in relief sculpture the vast extent of the imperial frontier.

With the emergence of the Parthians and Sassanids there was an appearance of new forms. Parthian innovations fully flowered during the Sassanid period with massive barrel-vaulted chambers, solid masonry domes, and tall columns. This influence was to remain for years to come. The roundness of the city of Baghdad in the Abbasid era for example, points to its Persian precedents such as Firouzabad in Fars.[29] The two designers who were hired by al-Mansur to plan the city's design were Naubakht, a former Persian Zoroastrian who also determined that the date of the foundation of the city would be astrologically auspicious, and Mashallah, a former Jew from Khorasan. The ruins of Persepolis, Ctesiphon, Jiroft,[30] Sialk, Pasargadae, Firouzabad, Arg-é Bam, and thousands of other ruins may give us merely a distant glimpse of what contribution Persians made to the art of building.

A well-preserved Persian column showing the details of the capital of the columns in Persepolis (Iran)

A well-preserved Persian column showing the details of the capital of the columns in Persepolis (Iran)

Tomb of Artaxerxes III at Persepolis

Tomb of Artaxerxes III at Persepolis

Islamic

Due to the extent of the Islamic conquests, Islamic architecture encompasses a wide range of architectural styles from the foundation of Islam to the present day. Both the religious and secular designs have influenced the design and construction of buildings and structures within and outside the sphere of Islamic culture. Islamic architecture is typically based on the idea of relating to the secular or the religious.[31] Some distinctive structures in Islamic architecture are mosques, tombs, palaces, baths, and forts, although Islamic architects have of course also applied their distinctive design precepts to domestic architecture.

The wide and long history of Islam has given rise to many local architectural styles, including Abbasid, Persian, Moorish, Moroccan, Timurid, Ottoman, Fatimid, Mamluk, Mughal, Indo-Islamic, Sino-Islamic and Afro-Islamic architecture. Notable Islamic architectural types include the early Abbasid buildings, T-type mosques, and the central-dome mosques of Anatolia. Islam does not encourage the worship of idols; therefore the architecture tends to be decorated with Arabic calligraphy from the Quran rather than illustrations of scenes from it.

Sudano-Sahelian: The Great Mosque of Djenné in present-day Mali, illustrating the mud construction of western Africa

Sudano-Sahelian: The Great Mosque of Djenné in present-day Mali, illustrating the mud construction of western Africa

.jpg.webp)

Africa

.jpg.webp)

Ethiopian architecture (including modern-day Eritrea) expanded from the Aksumite style and incorporated new traditions with the expansion of the Ethiopian state. Styles incorporated more wood and rounder structures in domestic architecture in the center of the country and the south, and these stylistic influences were manifested in the construction of churches and monasteries. Throughout the medieval period, Aksumite architecture and influences and its monolithic tradition persisted, with its influence strongest in the early medieval (Late Aksumite) and Zagwe periods (when the rock-cut monolithic churches of Lalibela were carved). Throughout the medieval period, and especially from the 10th to 12th centuries, churches were hewn out of rock throughout Ethiopia, especially during the northernmost region of Tigray, which was the heart of the Aksumite Empire. However, rock-hewn churches have been found as far south as Adadi Maryam (15th century), about 100 km south of Addis Abeba. The most famous example of Ethiopian rock-hewn architecture are the eleven monolithic churches of Lalibela, carved out of the red volcanic tuff found around the town. Though later medieval hagiographies attribute all eleven structures to the eponymous King Lalibela (the town was called Roha and Adefa before his reign), new evidence indicates that they may have been built separately over a period of a few centuries, with only a few of the more recent churches having been built under his reign. Archaeologist and Ethiopisant David Phillipson postulates, for instance, that Bete Gebriel-Rufa'el was actually built in the very early medieval period, some time between 600 and 800 A.D., originally as a fortress but was later turned into a church.[32]

During the early modern period, the absorption of new diverse influences such as Baroque, Arab, Turkish and Gujarati Indian style began with the arrival of Portuguese Jesuit missionaries in the 16th and 17th centuries. Portuguese soldiers had initially come in the mid-16th century as allies to aid Ethiopia in its fight against Adal, and later Jesuits came hoping to convert the country. Some Turkish influence may have entered the country during the late 16th century during its war with the Ottoman Empire (see Habesh), which resulted in an increased building of fortresses and castles. Ethiopia, naturally easily defensible because of its numerous ambas or flat-topped mountains and rugged terrain, yielded little tactical use from the structures in contrast to their advantages in the flat terrain of Europe and other areas, and so had until this point little developed the tradition. Castles were built especially beginning with the reign of Sarsa Dengel around the Lake Tana region, and subsequent Emperors maintained the tradition, eventually resulting in the creation of the Fasil Ghebbi (royal enclosure of castles) in the newly founded capital (1635), Gondar. Emperor Susenyos (r.1606-1632) converted to Catholicism in 1622 and attempted to make it the state religion, declaring it as such from 1624 until his abdication; during this time, he employed Arab, Gujarati (brought by the Jesuits), and Jesuit masons and their styles, as well as local masons, some of whom were Beta Israel. With the reign of his son Fasilides, most of these foreigners were expelled, although some of their architectural styles were absorbed into the prevailing Ethiopian architectural style. This style of the Gondarine dynasty would persist throughout the 17th and 18th centuries especially and also influenced modern 19th-century and later styles.

Great Zimbabwe is the largest medieval city in sub-Saharan Africa. By the late nineteenth century, most buildings reflected the fashionable European eclecticism and pastisched Mediterranean, or even Northern European, styles.

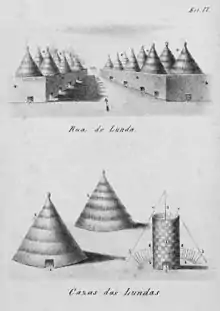

In the Western Sahel region, Islamic influence was a major contributing factor to architectural development from the later ages of the Kingdom of Ghana. At Kumbi Saleh, locals lived in domed-shaped dwellings in the king's section of the city, surrounded by a great enclosure. Traders lived in stone houses in a section which possessed 12 beautiful mosques, as described by al-bakri, with one centered on Friday prayer.[33] The king is said to have owned several mansions, one of which was sixty-six feet long, forty-two feet wide, contained seven rooms, was two stories high, and had a staircase; with the walls and chambers filled with sculpture and painting.[34]

Sahelian architecture initially grew from the two cities of Djenné and Timbuktu. The Sankore Mosque in Timbuktu, constructed from mud on timber, was similar in style to the Great Mosque of Djenné. The rise of kingdoms in the West African coastal region produced architecture which drew on indigenous traditions, utilizing wood. The famed Benin City, destroyed by the Punitive Expedition, was a large complex of homes in coursed clay, with hipped roofs of shingles or palm leaves. The Palace had a sequence of ceremonial rooms, and was decorated with brass plaques.

A common type of houses in Sub-Saharian Africa were the beehive houses, made from a circle of stones topped with a domed roof. The ancient Bantu used this type of house, which was made with mud, poles, and cow dung.

A traditional tata-somba house in Benin

A traditional tata-somba house in Benin

Illustration from 1854 of Lunda street and houses

Illustration from 1854 of Lunda street and houses

Southern Asia

Indian

Indian architecture encompasses a wide variety of geographically and historically spread structures, and was transformed by the history of the Indian subcontinent. The result is an evolving range of architectural production that, although it is difficult to identify a single representative style, nonetheless retains a certain amount of continuity across history. The diversity of Indian culture is represented in its architecture. It is a blend of ancient and varied native traditions, with building types, forms and technologies from West and Central Asia, as well as Europe. Architectural styles range from Hindu temple architecture to Islamic architecture to western classical architecture to modern and post-modern architecture.

India's Urban Civilization is traceable originally to Mohenjodaro and Harappa, now in Pakistan. From then on, Indian architecture and civil engineering continued to develop, manifesting in temples, palaces and forts across the Indian subcontinent and neighbouring regions. Architecture and civil engineering was known as sthapatya-kala, literally "the art of constructing".

Indian rock-cut architecture provides the earliest complete survivals of Buddhist, Jain and Hindu temples. The temples of Aihole and Pattadakal are well-known early examples of Hindu temple architecture, when the temple was taking on its final form. This was more or less set out in the Sulbasutras, appendices to the Vedas giving rules for constructing altars, with detailed geometrical and ritual requirements. "They contained quite an amount of geometrical knowledge, but the mathematics was being developed, not for its own sake, but purely for practical religious purposes."[35] Nonetheless, there is great variety in the details and decoration of regional and period styles, for example in Hoysala architecture, Vijayanagara architecture and Western Chalukya architecture.

During the Mauryan Empire and Kushan Empire, Indian architecture and civil engineering reached regions like Baluchistan and Afghanistan. Statues of Buddha were cut out, covering entire mountain cliffs, like in Buddhas of Bamyan, Afghanistan. Over a period of time, the ancient Indian art of construction blended with Greek styles and spread to Central Asia.

The rule of the Delhi Sultanate, Deccan Sultanates and Mughal Empire led to the development of Indo-Islamic architecture, a style that combined Islamic influences with traditional Indian styles.

During the British Raj, a new style of architecture known as the Indo-Saracenic revival style developed, which incorporated varying degrees of Indian elements into the British style. The Churches and convents of Goa which is cast in the Indian Baroque Architectural style under the orientation of the most eminent architects of the time. It is a prime example of the blending of traditional Indian styles with western European architectural styles.

Detail of the Meenakshi Temple

Detail of the Meenakshi Temple.jpg.webp)

Buddhist

Buddhist religious architecture developed in the Indian subcontinent. Three types of structures are associated with the religious architecture of early Buddhism: monasteries (vihāras), places to venerate relics (stupas), and shrines or prayer halls (chaityas, also called chaitya grihas), which later came to be called temples in some places. The initial function of a stupa was the veneration and safe-guarding of the relics of Gautama Buddha. The earliest surviving example of a stupa is in Sanchi (Madhya Pradesh).

When Buddhism came to China, Buddhist architecture came along with it. There were many monasteries built, equalling about 45,000. These monasteries were filled with examples of Buddhist architecture, and because of this, they hold a very prominent place in Chinese architecture. One of the earliest surviving examples is the brick pagoda at the Songyue Monastery in Dengfeng County.

The 26th Cave, one of the Ajanta Caves, from the 5th century AD

The 26th Cave, one of the Ajanta Caves, from the 5th century AD

The Great Stupa at Sanchi (Madhya Pradesh, India)

The Great Stupa at Sanchi (Madhya Pradesh, India)

Wat Phra Kaew in Bangkok (Thailand), completed in the 18th century

Wat Phra Kaew in Bangkok (Thailand), completed in the 18th century

Southeast Asia

Oc Eo Culture

Possibly the earliest examples of South East Asian architecture are Hindu temples excavated from Cay Thi mound of the Óc Eo culture from the Mekong Delta, Southern Vietnam carbon-dated between the 2nd century BC to 7th century AD and constructed using granite stone and burnt bricks. The temple contains a cylindrical pillar in the shape of Swastika, which was previously mistaken for a tomb and a square stepped pond.[36]

Cambodian (Khmer)

The main evidence of Khmer architecture and ultimately for Khmer civilization, however, remains the religious buildings, considerable in number and extremely varied in size. They were destined for immortal gods and as they were built of durable materials of brick, laterite and sandstone, many have survived to the present day. They were usually surrounded by enclosures to protect them from evil powers but confusion has often arisen as to which is a temple enclosure and which is that of the town of which the temple was a part. [37]

Angkor Wat temple is a great example of Khmer architectural masterpiece, was built by king Suryavarman II in the 12th century. Despite the fact that it is over 800 years old, it has still maintained its top rank to be the world's largest religious structure.

.jpg.webp) The Bakong is the earliest surviving Temple Mountain at Angkor, completed in 881 AD

The Bakong is the earliest surviving Temple Mountain at Angkor, completed in 881 AD

Cruciform gallery separates the courtyards at Angkor Wat

Cruciform gallery separates the courtyards at Angkor Wat Khmer pediment, from 976, made of pink sandstone, dimensions: 196 x 269 cm, in Musée Guimet (Paris)

Khmer pediment, from 976, made of pink sandstone, dimensions: 196 x 269 cm, in Musée Guimet (Paris)

Indonesian

The architecture of Indonesia reflects both the cultural diversity of the region and its rich historical inheritance. The geographic position of Indonesia means a transition between the culture of Asian Hindu-Buddhism architecture and animistic architecture of Oceania. Indonesian wide range of vernacular styles is the legacy of an Austronesian architectural tradition characterized by wooden pile dwellings, high pitched roofs and extended roof ridges. The temples of Java, on the other hand, share an Indian Hindu-Buddhist ancestry, typical of Southeast Asia; though indigenous influences have led to the creation of a distinctly Indonesian style of monumental architecture.

Gradual spread of Islam through the region from the 12th century onwards creates an Islamic architecture which betray a mixture of local and exotic elements. Arrival of the European merchant, especially the Dutch, shows incorporation of many Indonesian features into the architecture of the native Netherlands to produce an eclectic synthesis of Eastern and Western forms apparent in the early 18th-century Indies Style and modern New Indies Style. The years that followed independence saw the adoption of Modernist agenda on the part of Indonesian architects apparent in the architecture of the 1970s and 1980s.

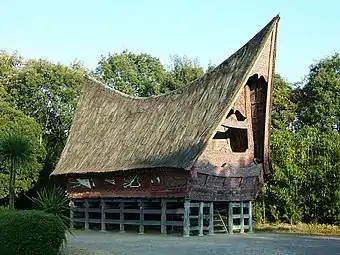

A traditional Batak Toba house in North Sumatra

A traditional Batak Toba house in North Sumatra A traditional house in Nias (North Sumatra)

A traditional house in Nias (North Sumatra)

Oceanic

Most Oceanic buildings consist of huts, made of wood and other vegetal materials. Art and architecture have often been closely connected—for example, storehouses and meetinghouses are often decorated with elaborate carvings—and so they are presented together in this discussion. The architecture of the Pacific Islands was varied and sometimes large in scale. Buildings reflected the structure and preoccupations of the societies that constructed them, with considerable symbolic detail. Technically, most buildings in Oceania were no more than simple assemblages of poles held together with cane lashings; only in the Caroline Islands were complex methods of joining and pegging known.

An important Oceanic archaeological site is Nan Madol from the Federated States of Micronesia. Nan Madol was the ceremonial and political seat of the Saudeleur Dynasty, which united Pohnpei's estimated 25,000 people until about 1628.[38] Set apart between the main island of Pohnpei and Temwen Island, it was a scene of human activity as early as the first or second century AD. By the 8th or 9th century, islet construction had started, with construction of the distinctive megalithic architecture beginning 1180–1200 AD.[39]

Photo of a native house from New Caledonia, circa 1906

Photo of a native house from New Caledonia, circa 1906 Men's club house, 1907, from Palau, now in Ethnological Museum of Berlin

Men's club house, 1907, from Palau, now in Ethnological Museum of Berlin Detail of a ceremonial supply house, from Papua New Guinea, now in Ethnological Museum of Berlin

Detail of a ceremonial supply house, from Papua New Guinea, now in Ethnological Museum of Berlin Traditional house in Micronesia

Traditional house in Micronesia

Eastern Asia

Chinese

Chinese architecture refers to a style of architecture that has taken shape in East Asia over many centuries. Especially Japan, Korea, Vietnam and Ryukyu. The structural principles of Chinese architecture have remained largely unchanged, the main changes being only the decorative details. Since the Tang Dynasty, Chinese architecture has had a major influence on the architectural styles of Korea, Vietnam, and Japan.

From the Neolithic era Longshan Culture and Bronze Age era Erlitou culture, the earliest rammed earth fortifications exist, with evidence of timber architecture. The subterranean ruins of the palace at Yinxu dates back to the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600 BC–1046 BC). In historic China, architectural emphasis was laid upon the horizontal axis, in particular the construction of a heavy platform and a large roof that floats over this base, with the vertical walls not as well emphasized. This contrasts Western architecture, which tends to grow in height and depth. Chinese architecture stresses the visual impact of the width of the buildings. The deviation from this standard is the tower architecture of the Chinese tradition, which began as a native tradition and was eventually influenced by the Buddhist building for housing religious sutras — the stupa — which came from Nepal. Ancient Chinese tomb model representations of multiple story residential towers and watchtowers date to the Han Dynasty (202 BC–220 AD). However, the earliest extant Buddhist Chinese pagoda is the Songyue Pagoda, a 40 m (131 ft) tall circular-based brick tower built in Henan province in the year 523 AD. From the 6th century onwards, stone-based structures become more common, while the earliest are from stone and brick arches found in Han Dynasty tombs. The Zhaozhou Bridge built from 595 to 605 AD is China's oldest extant stone bridge, as well as the world's oldest fully stone open-spandrel segmental arch bridge.

The vocational trade of architect, craftsman, and engineer was not as highly respected in premodern Chinese society as the scholar-bureaucrats who were drafted into the government by the civil service examination system. Much of the knowledge about early Chinese architecture was passed on from one tradesman to his son or associative apprentice. However, there were several early treatises on architecture in China, with encyclopedic information on architecture dating back to the Han Dynasty. The height of the classical Chinese architectural tradition in writing and illustration can be found in the Yingzao Fashi, a building manual written by 1100 and published by Li Jie (1065–1110) in 1103. In it there are numerous and meticulous illustrations and diagrams showing the assembly of halls and building components, as well as classifying structure types and building components.

There were certain architectural features that were reserved solely for buildings built for the Emperor of China. One example is the use of yellow roof tiles; yellow having been the Imperial color, yellow roof tiles still adorn most of the buildings within the Forbidden City. The Temple of Heaven, however, uses blue roof tiles to symbolize the sky. The roofs are almost invariably supported by brackets, a feature shared only with the largest of religious buildings. The wooden columns of the buildings, as well as the surface of the walls, tend to be red in colour.

Many current Chinese architectural designs follow post-modern and western styles.

Detail of a colorful column from a gate

Detail of a colorful column from a gate Traditional Chinese garden in Hangzhou (China)

Traditional Chinese garden in Hangzhou (China) Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests, the main building of the Temple of Heaven (Beijing)

Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests, the main building of the Temple of Heaven (Beijing)

Korean

The basic construction form is more or less similar to Eastern Asian building system. From a technical point of view, buildings are structured vertically and horizontally. A construction usually rises from a stone subfoundation to a curved roof covered with tiles, held by a console structure and supported on posts; walls are made of earth (adobe) or are sometimes totally composed of movable wooden doors. Architecture is built according to the k'an unit, the distance between two posts (about 3.7 meters), and is designed so that there is always a transitional space between the "inside" and the "outside."

The console, or bracket structure, is a specific architectonic element that has been designed in various ways through time. If the simple bracket system was already in use under the Goguryeo kingdom (37 BCE–668 CE)—in palaces in Pyongyang, for instance—a curved version, with brackets placed only on the column heads of the building, was elaborated during the early Koryo dynasty (918–1392). The Amita Hall of the Pusok temple in Antong is a good example. Later on (from the mid-Koryo period to the early Choson dynasty), a multiple-bracket system, or an inter-columnar-bracket set system, was developed under the influence of Mongol's Yuan dynasty (1279–1368). In this system, the consoles were also placed on the transverse horizontal beams. Seoul's Namtaemun Gate Namdaemun, Korea's foremost national treasure, is perhaps the most symbolic example of this type of structure.

In the mid-Choson period, the winglike bracket form appeared (one example is the Yongnyongjon Hall of Jongmyo, Seoul), which is interpreted by many scholars as an example of heavy Confucian influence in Joseon Korea, which emphasized simplicity and modesty in such shrine buildings. Only in buildings of importance like palaces or sometimes temples (Tongdosa, for instance) were the multicluster brackets still used. Confucianism also led to more sober and simple solutions.

The Dabo Pagoda in Bulguksa, built in circa 751 AD

The Dabo Pagoda in Bulguksa, built in circa 751 AD Throne Hall of the Gyeongbokgung Palace in Seoul (South Korea)

Throne Hall of the Gyeongbokgung Palace in Seoul (South Korea)_(26242969507).jpg.webp) The Changdeokgung Palace, built in 1405

The Changdeokgung Palace, built in 1405

Japanese

Japanese architecture has as long a history as any other aspect of Japanese culture. It also shows a number of important differences and aspects which are uniquely Japanese.

Two new forms of architecture were developed in medieval Japan in response to the militaristic climate of the times: the castle, a defensive structure built to house a feudal lord and his soldiers in times of trouble; and the shoin, a reception hall and private study area designed to reflect the relationships of lord and vassal within a feudal society.

Because of the need to rebuild Japan after World War II, major Japanese cities contain numerous examples of modern architecture. Japan played some role in modern skyscraper design, because of its long familiarity with the cantilever principle to support the weight of heavy tiled temple roofs. New city planning ideas based on the principle of layering or cocooning around an inner space (oku), a Japanese spatial concept that was adapted to urban needs, were adapted during reconstruction.

Hōryū-ji (literally Temple of the Flourishing Law), a Buddhist temple in Ikaruga (Nara Prefecture), built in the 7th century

Hōryū-ji (literally Temple of the Flourishing Law), a Buddhist temple in Ikaruga (Nara Prefecture), built in the 7th century Kinkaku-ji (literally "Temple of the Golden Pavilion"), a Zen Buddhist temple in Kyoto, originally built in 1397

Kinkaku-ji (literally "Temple of the Golden Pavilion"), a Zen Buddhist temple in Kyoto, originally built in 1397 Interior of the Kumamoto Castle in Kumamoto (Kumamoto Prefecture), built in 1467, demolished in 1877 and rebuilt in 1960

Interior of the Kumamoto Castle in Kumamoto (Kumamoto Prefecture), built in 1467, demolished in 1877 and rebuilt in 1960

Pre-Columbian

Mesoamerican

Mesoamerican architecture is the set of architectural traditions produced by pre-Columbian cultures and civilizations of Mesoamerica, (such as the Olmec, Maya, and Aztec) traditions which are best known in the form of public, ceremonial and urban monumental buildings and structures. The distinctive features of Mesoamerican architecture encompass a number of different regional and historical styles, which however are significantly interrelated. These styles developed throughout the different phases of Mesoamerican history as a result of the intensive cultural exchange between the different cultures of the Mesoamerican culture area through thousands of years. Mesoamerican architecture is mostly noted for its pyramids which are the largest such structures outside of Ancient Egypt. The Mezcala culture (700–200 BC) is known for its temple shaped sculptures, usually with an anthropomorphic person in the middle.

Mezcala temple model with a figure in centre, 1st–8th century, made of stone, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City)

Mezcala temple model with a figure in centre, 1st–8th century, made of stone, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York City) The Mayan temple El Castillo, also known as the Temple of Kukulcan, built between 9th and 12th centuries in Yucatán (Mexico)

The Mayan temple El Castillo, also known as the Temple of Kukulcan, built between 9th and 12th centuries in Yucatán (Mexico) Overview of the central plaza of the Mayan city of Palenque (Chiapas, Mexico), a fine example of Classic period Mesoamerican architecture

Overview of the central plaza of the Mayan city of Palenque (Chiapas, Mexico), a fine example of Classic period Mesoamerican architecture.jpg.webp) Teotihuacan style architecture displaying decorative ornamentation made of obsidian and shell inlaid into a painted cantera surface set upon a tezontle interior

Teotihuacan style architecture displaying decorative ornamentation made of obsidian and shell inlaid into a painted cantera surface set upon a tezontle interior

Inca

Incan architecture consists of the major construction achievements developed by the Incas. The Incas developed an extensive road system spanning most of the western length of the continent. Inca rope bridges could be considered the world's first suspension bridges. Because the Incas used no wheels (It would have been impractical for the terrain) or horses, they built their roads and bridges for foot and pack-llama traffic. Much of present-day architecture at the former Inca capital Cuzco shows both Incan and Spanish influences. The famous lost city Machu Picchu is the best surviving example of Incan architecture. Another significant site is Ollantaytambo. The Inca were sophisticated stone cutters whose masonry used no mortar.

View of Machu Picchu in Peru, built in circa 1450 AD

View of Machu Picchu in Peru, built in circa 1450 AD The Main Temple of Machu Picchu

The Main Temple of Machu Picchu The Twelve-angled stone, part of a stone wall of an Inca palace, and a national heritage object

The Twelve-angled stone, part of a stone wall of an Inca palace, and a national heritage object Ashlar polygonal masonry at Sacsayhuamán

Ashlar polygonal masonry at Sacsayhuamán

Ancient of North America

Inside what is the present-day United States, the Mississippians[40] and the Pueblo[41] created substantial public architecture. The Mississippian culture was among the mound-building peoples, noted for construction of large earthen platform mounds.

Impermanent buildings, which were often architecturally unique from region to region, continue to influence American architecture today. In his summary, "The World of Textiles", North Carolina State's Tushar Ghosh provides one example: the Denver International Airport's roof is a fabric structure that was influenced by and/or resembles the tipis of local cultures. In writing about Evergreen State College, Lloyd Vaughn lists an example of very different native architecture that also influenced contemporary building: the Native American Studies program is housed in a modern-day longhouse derived from pre-Columbian Pacific Northwest architecture.

Cliff Palace of Mesa Verde, in Colorado (USA) created by the Ancestral Puebloans

Cliff Palace of Mesa Verde, in Colorado (USA) created by the Ancestral Puebloans Taos Pueblo, an ancient pueblo belonging to a Taos-speaking (Tiwa) Native American tribe of Puebloan people, in Taos Pueblo, (New Mexico, USA)

Taos Pueblo, an ancient pueblo belonging to a Taos-speaking (Tiwa) Native American tribe of Puebloan people, in Taos Pueblo, (New Mexico, USA) The Navajo National Monument, in northern Arizona (USA)

The Navajo National Monument, in northern Arizona (USA) A book illustration of an Inuit village, Oopungnewing, near Frobisher Bay on Baffin Island (Canada) in the mid-19th century

A book illustration of an Inuit village, Oopungnewing, near Frobisher Bay on Baffin Island (Canada) in the mid-19th century

Europe to 1600

Medieval

Surviving examples of medieval secular architecture mainly served for defense. Castles and fortified walls provide the most notable remaining non-religious examples of medieval architecture. Windows gained a cross-shape for more than decorative purposes: they provided a perfect fit for a crossbowman to safely shoot at invaders from inside. Crenellation walls (battlements) provided shelters for archers on the roofs to hide behind when not shooting.

Byzantine

The Byzantine Empire gradually emerged as a distinct artistic and cultural entity from the Roman Empire after AD 330, when the Roman Emperor Constantine the Great moved the capital of the Roman Empire east from Rome to Byzantium (later renamed Constantinople and now called Istanbul). The empire endured for more than a millennium, dramatically influencing Medieval and Renaissance-era architecture in Europe and, following the capture of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks in 1453, leading directly to the architecture of the Ottoman Empire.

Early Byzantine architecture was built as a continuation of Roman architecture. Stylistic drift, technological advancement, and political and territorial changes meant that a distinct style gradually emerged, which imbued certain influences from the Near East and used the Greek cross plan in church architecture. Buildings increased in geometric complexity, brick and plaster were used in addition to stone in the decoration of important public structures, classical orders were used more freely, mosaics replaced carved decoration, complex domes rested upon massive piers, and windows filtered light through thin sheets of alabaster to softly illuminate interiors. This Byzantine style, with increasingly exotic domes and ever-richer mosaics, traveled west to Ravenna and Venice and as far north as Moscow. Most of the churches and basilicas have high-riding domes. As result, they created vast open spaces at the centres of churches, heightening the sense of grace and light. The round arch is a fundamental of Byzantine style. Magnificent golden mosaics with their graphic simplicity and immense power brought light and warmth into the heart of churches. Byzantine capitals break away from the Classical conventions of ancient Greece and Rome. Sinuous lines and naturalistic forms are precursors to the Gothic style.

According to descriptions, interiors were plated with marble or stone. Some of the columns were also made of marble. Other widely used materials were bricks and stone, not just marble like in Classical antiquity.[42] Mural paintings or mosaics made of shiny little stones were also elements of interior architecture. Precious wood furniture like beds, chairs, stools, tables, bookshelves and silver or golden cups with beautiful reliefs, decorated Byzantine interiors.[43]

Apse of the Santa Maria Maggiore church in Rome, decorated in the 5th century with this glamorous mosaic

Apse of the Santa Maria Maggiore church in Rome, decorated in the 5th century with this glamorous mosaic

Mosaics on a ceiling and some walls of the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna (Italy), circa 547 AD

Mosaics on a ceiling and some walls of the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna (Italy), circa 547 AD.jpg.webp) The Church of Saint Sophia from Ohrid (North Macedonia), completed in the 9th century AD

The Church of Saint Sophia from Ohrid (North Macedonia), completed in the 9th century AD The Church of St. George from Staro Nagoričane (North Macedonia), founded in 1071, built in the Serbo-Byzantine style

The Church of St. George from Staro Nagoričane (North Macedonia), founded in 1071, built in the Serbo-Byzantine style The Little Metropolis in Athens, built on unknown dates, between the 9th century to the 13th century

The Little Metropolis in Athens, built on unknown dates, between the 9th century to the 13th century The northern façade of the Palace of the Porphyrogenitus, before the modern renovation, from the late 13th-century

The northern façade of the Palace of the Porphyrogenitus, before the modern renovation, from the late 13th-century.jpg.webp) One of the mosaics from the St Mark's Basilica (Venice)

One of the mosaics from the St Mark's Basilica (Venice)

Romanesque

Western European architecture in the Early Middle Ages may be divided into Early Christian and Pre-Romanesque, including Merovingian, Carolingian, Ottonian, and Asturian. While these terms are problematic, they nonetheless serve adequately as entries into the era. Considerations that enter into histories of each period include Trachtenberg's "historicising" and "modernising" elements, Italian versus northern, Spanish, and Byzantine elements, and especially the religious and political maneuverings between kings, popes, and various ecclesiastic officials.

Romanesque, prevalent in medieval Europe during the 11th and 12th centuries, was the first pan-European style since Roman Imperial architecture and examples are found in every part of the continent. The term was not contemporary with the art it describes, but rather, is an invention of modern scholarship based on its similarity to Roman architecture in forms and materials. Romanesque is characterized by a use of round or slightly pointed arches, barrel vaults, and cruciform piers supporting vaults.

Interior of the Durham Cathedral in Durham (England), built between 1093 and 1133, additions until 1490

Interior of the Durham Cathedral in Durham (England), built between 1093 and 1133, additions until 1490.jpg.webp)

Maria Laach Abbey, situated on the southwestern shore of the Laacher See (Lake Laach), near Andernach (Germany), built in the 11th-12th centuries

Maria Laach Abbey, situated on the southwestern shore of the Laacher See (Lake Laach), near Andernach (Germany), built in the 11th-12th centuries Part of a stained glass window from Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Strasbourg in Strasbourg (France)

Part of a stained glass window from Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Strasbourg in Strasbourg (France)

Gothic

The various elements of Gothic architecture emerged in a number of 11th- and 12th-century building projects, particularly in the Île de France area, but were first combined to form what we would now recognise as a distinctively Gothic style at the 12th-century abbey church of Saint-Denis in Saint-Denis, near Paris. Verticality is emphasized in Gothic architecture, which features almost skeletal stone structures with great expanses of glass, pared-down wall surfaces supported by external flying buttresses, pointed arches using the ogive shape, ribbed vaults, clustered columns, pinnacles and sharply pointed spires and spirelets. Windows contain beautiful stained glass, showing stories from the Bible and from lives of saints. Such advances in design allowed cathedrals to rise taller than ever, and it became something of an inter-regional contest to build a church as high as possible.

Part of the Royal Portal, circa 1145–1155, of the Chartres Cathedral (Chartres, France)

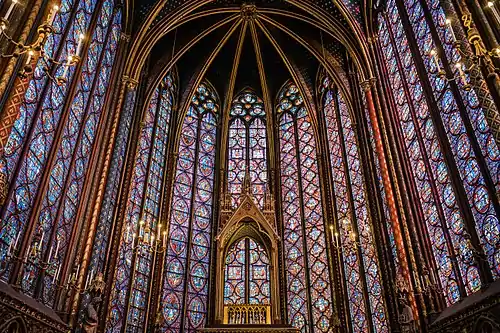

Part of the Royal Portal, circa 1145–1155, of the Chartres Cathedral (Chartres, France) Stained glass windows of the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, completed in 1248, mostly constructed between 1194 and 1220

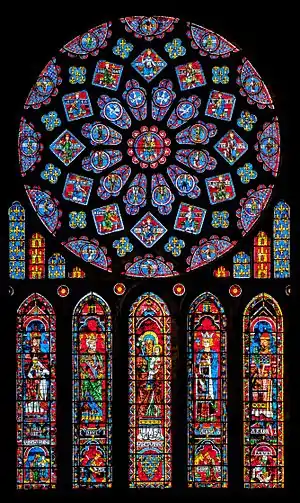

Stained glass windows of the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, completed in 1248, mostly constructed between 1194 and 1220 North transept windows, circa 1230–1235, in the Chartres Cathedral

North transept windows, circa 1230–1235, in the Chartres Cathedral The Church of Our Blessed Lady of the Sablon, built in the Sablon/Zavel district in the historic centre of Brussels (Belgium), built between the 13th-15th centuries

The Church of Our Blessed Lady of the Sablon, built in the Sablon/Zavel district in the historic centre of Brussels (Belgium), built between the 13th-15th centuries The Brussels Town Hall, built between 1402 and 1420 in the famous Grand Place

The Brussels Town Hall, built between 1402 and 1420 in the famous Grand Place Altar in the knight's chapel in Haßfurt am Main (Bavaria, Germany)

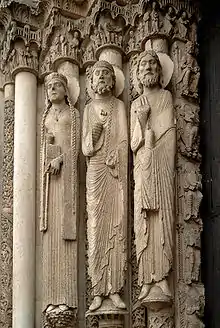

Altar in the knight's chapel in Haßfurt am Main (Bavaria, Germany) Statues in the central tympanum of the Chartres Cathedral, about 80 km (50 miles) southwest of Paris

Statues in the central tympanum of the Chartres Cathedral, about 80 km (50 miles) southwest of Paris

Foliage on capitals at the Southwell Minster (Southwell, England)

Foliage on capitals at the Southwell Minster (Southwell, England) Flamboyant Gothic cross-windows of the Hôtel de Sens (Paris)

Flamboyant Gothic cross-windows of the Hôtel de Sens (Paris)

Russian

The architectural history of Russia is conditioned by Orthodox Eastern Europe: unlike the West, yet similarly, if tenuously, linked with the traditions of classical antiquity (through Byzantium). It has experienced from time to time westernising movements that culminated in the comprehensive reforms of Peter the Great (around 1700). From prehistoric times the material of vernacular Russian architecture was wood. Byzantine churches and the architecture of Kievan Rus were characterized by broader, flatter domes without a special framework erected above the drum. In contrast to this ancient form, each drum of a Russian church is surmounted by a special structure of metal or timber, which is lined with sheet iron or tiles. Some characteristics taken from the Slavic pagan temples are the exterior galleries and the plurality of towers.

The Saint Basil's Cathedral is one of Russia's most distinctive sights. Built by Tsar Ivan IV (also known as Ivan the Terrible) to commemorate his defeat of the Mongols at the battle Kazan in 1552, it stands just outside the Kremlin in the Red Square, in the heart of Moscow. Its extraordinary onion-shaped domes, painted in bright colours, create a memorable skyline, making St. Basil's Cathedral a symbol both of Moscow and Russia as a whole.[44] Each of the domes has its own dazzling form of decoration, ranging from prisms and spirals to chevrons and stripes, all emphasised with brilliant colours. Their colours are unusual, most of the Russian domes being either plain or gilded. Originally, the dome at St. Basil's Cathedral had a gold finish, with some blue and green ceramic decoration. The bright, painted colours were added at various times from the 17th to the 19th century.[45]

Interior of the Palace of Facets, part of the Moscow Kremlin, built between 1487 and 1492

Interior of the Palace of Facets, part of the Moscow Kremlin, built between 1487 and 1492 The Spasskaya Tower, one of the towers of the Moscow Kremlin, which overlooks the Red Square, built in 1491

The Spasskaya Tower, one of the towers of the Moscow Kremlin, which overlooks the Red Square, built in 1491.jpg.webp) Interior of Saint Basil's Cathedral, full of icons painted in the Byzantine style

Interior of Saint Basil's Cathedral, full of icons painted in the Byzantine style St. John the Baptist Church, built between 1671 and 1687, on the bank of Kotorosl river in the Tolchkovo Sloboda (district)

St. John the Baptist Church, built between 1671 and 1687, on the bank of Kotorosl river in the Tolchkovo Sloboda (district)

Renaissance

The Renaissance often refers to the Italian Renaissance that began in the 14th century, but recent research has revealed the existence of similar movements around Europe before the 15th century; consequently, the term "Early Modern" has gained popularity in describing this cultural movement. This period of cultural rebirth is often credited with the restoration of scholarship in the Classical antiquities and the absorption of new scientific and philosophical knowledge that fed the arts.

The development from Medieval architecture concerned the way geometry mediated between the intangibility of light and the tangibility of the material as a way of relating divine creation to mortal existence. This relationship was changed in some measure by the invention of perspective, which brought a sense of infinity into the realm of human comprehension through the new representations of the horizon, evidenced in the expanses of space opened up in Renaissance art, and helped shape new humanist thought.

Perspective represented a new understanding of space as a universal, a priori fact, understood and controllable through human reason. Renaissance buildings therefore show a different sense of conceptual clarity, where spaces were designed to be understood in their entirety from a specific fixed viewpoint. The power of perspective to universally represent reality was not limited to describing experiences, but also allowed it to anticipate experience itself by projecting the image back into reality.

The Renaissance spread to France in the late 15th century, when Charles VIII returned in 1496 with several Italian artists from his conquest of Naples. Renaissance chateaux were built in the Loire Valley, the earliest example being the Château d'Amboise, and the style became dominant under Francis I (1515–47). (See Châteaux of the Loire Valley). The Château de Chambord is a combination of Gothic structure and Italianate ornament, a style which progressed under architects such as Sebastiano Serlio, who was engaged after 1540 in work at the Château de Fontainebleau.

Architects such as Philibert Delorme, Androuet du Cerceau, Giacomo Vignola, and Pierre Lescot, were inspired by the new ideas. The southwest interior facade of the Cour Carrée of the Louvre in Paris was designed by Lescot and covered with exterior carvings by Jean Goujon. Architecture continued to thrive in the reigns of Henry II and Henry III.

In England, the first great exponent of Renaissance architecture was Inigo Jones (1573–1652), who had studied architecture in Italy where the influence of Andrea Palladio was very strong. Jones returned to England full of enthusiasm for the new movement and immediately began to design such buildings as the Queen's House at Greenwich in 1616 and the Banqueting House at Whitehall three years later. These works with their clean lines and symmetry, were revolutionary in a country still enamoured with mullion windows, crenellations and turrets.

The Florence Cathedral, built between 1296 and 1436 in Florence (Italy)

The Florence Cathedral, built between 1296 and 1436 in Florence (Italy)

.jpg.webp)

Medallion and a Corinthian pilaster's capital, on Hôtel du Vieux-Raisin

Medallion and a Corinthian pilaster's capital, on Hôtel du Vieux-Raisin Various ornaments widely used in Renaissance applied arts, including putti and festoons, on a wall of the Hôtel du Vieux-Raisin

Various ornaments widely used in Renaissance applied arts, including putti and festoons, on a wall of the Hôtel du Vieux-Raisin.jpg.webp)

The Château de Chenonceau, built between 1514 and 1522 in France

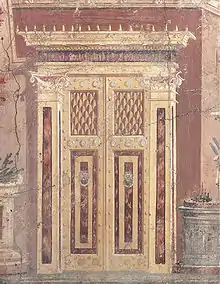

The Château de Chenonceau, built between 1514 and 1522 in France'_-'Plusieurs_Menuiseries_(...)'-_MET_DP830821.jpg.webp) Designs of two wooden portals, by Paul Vredeman de Vries

Designs of two wooden portals, by Paul Vredeman de Vries

European and colonial architecture

With the rise of various European colonial empires from the 16th century onward through the early 20th century, the new stylistic trends of Europe were exported to or adopted by locations around the world, often evolving into new regional variations.

Baroque

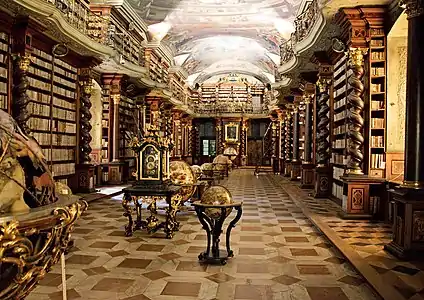

.JPG.webp)

The Baroque and its late variant the Rococo were the first truly global styles in the arts. Dominating more than two centuries of art and architecture in Europe, Latin America and beyond from circa 1580 to circa 1800, they were the first to focus so intensely on their impact on the viewer, and they owed much of their popularity and global scope to this visual allure. Born in the painting studios of Bologna and Rome in the 1580s and 1590s, and in Roman sculptural and architectural ateliers in the second and third decades of the 17th century, the Baroque spread swiftly throughout Italy, Spain and Portugal, Flanders, France, the Netherlands, England, Scandinavia, and Russia, as well as to central and eastern European centres from Munich (Germany) to Vilnius (Lithuania).[46]

Baroque architecture originated in 17th century Rome, where it developed as an expression on the newly triumphant Catholic Church. The Counter-Reformation stated that architecture, painting and sculpture would play an important role in transforming Rome into a truly Catholic city. The streets radiating from St. Peters Cathedral were soon dotted with reminders of the victorious faith. Breaking with the somewhat static intellectual formulas of the Renaissance, Baroque architecture was first and foremost an art of persuasion.[47] The periods of Mannerism and the Baroque that followed it signalled an increasing anxiety over meaning and representation. Important developments in science and philosophy had separated mathematical representations of reality from the rest of culture, fundamentally changing the way humans related to their world through architecture. It would reach its most extreme and embellished development under the decorative tastes of Rococo.

Baroque architects took the basic elements of Renaissance architecture, including domes and colonnades, and made them higher, grander, more decorated, and more dramatic. The interior effects were often achieved with the use of quadratura, or trompe-l'œil painting combined with sculpture: the eye is drawn upward, giving the illusion that one is looking into the heavens. Clusters of sculpted angels and painted figures crowd the ceiling. Light was also used for dramatic effect; it streamed down from cupolas and was reflected from an abundance of gilding. Solomonic columns were often used, to give an illusion of upwards motion and other decorative elements occupied every available space. In Baroque palaces, grand stairways became a central element.[48] A characteristically Baroque form of ornamentation, the cartouche is an oval panel with crested or scrolled borders, used on palace, house and church façades as a framing device for a monogram (of the owner, the architect or the person to whom it is dedicated), cresting or coat of arms, but also as a purely decorative infill motif. It usually features inside a broken pediment, over an entrance or in the axis from the one to the other.[49][50]

.jpg.webp) Dome of the Church of the Gesù (Rome), made in 1674 by Giovanni Battista Gaulli

Dome of the Church of the Gesù (Rome), made in 1674 by Giovanni Battista Gaulli Interior of the church of the Melk Abbey, the abbey being built between 1702 and 1736

Interior of the church of the Melk Abbey, the abbey being built between 1702 and 1736.jpg.webp)

Entrance of the Palace Square façade of the Winter Palace (Sankt Petersburg, Russia), the official residence of the Russian Emperors from 1732 to 1917

Entrance of the Palace Square façade of the Winter Palace (Sankt Petersburg, Russia), the official residence of the Russian Emperors from 1732 to 1917 The Smolny Cathedral from Saint Petersburg (Russia), by Bartolomeo Rastrelli, built between 1748 and 1764

The Smolny Cathedral from Saint Petersburg (Russia), by Bartolomeo Rastrelli, built between 1748 and 1764.jpg.webp) The Trevi Fountain, one of the most iconic monuments of Rome, designed by Italian architect Nicola Salvi and completed by Giuseppe Pannini and several others

The Trevi Fountain, one of the most iconic monuments of Rome, designed by Italian architect Nicola Salvi and completed by Giuseppe Pannini and several others

Rococo

The Rococo style was essentially a decorative movement that developed in the early 18th century in the town houses and hôtels particuliers of the Parisian nobility. Although the style originated in the rich decoration at the Palace of Versailles, it was also a reaction to the formality of the royal palace. Juste-Aurèle Meissonnier, Gilles-Marie Oppenordt, Nicolas Pineau and Germain Boffrand were among the designers who succeeded in reflecting the more intimate scale and comfortable arrangement of rooms by decorating them with light, frivolous and colourful schemes in which panels and door-frames dissolved and walls merged with the ceiling. The repertoire of motifs, including Rocaille arabesques and chinoiseries, was infinitely varied. Characteristic of the style were Rocaille motifs derived from the shells, icicles and rockwork or grotto decoration. Rocaille arabesques were mostly abstract forms, laid out symmetrically over and around architectural frames. A favourite motif was the scallop shell, whose top scrolls echoed the basic S and C framework scrolls of the arabesques and whose sinuous ridges echoed the general curvilinearity of the room decoration. While few Rococo exteriors were built in France, a number of Rococo churches are found in southern Germany.[51] Other widely-user motifs in decorative arts and interior architecture include: asymmetrical shells, acanthus and other leaves, birds, bouquets of flowers, fruits, angels and Far Eastern elements.[52]