2006 Montenegrin independence referendum

An independence referendum was held in Montenegro on 21 May 2006.[1] It was approved by 55.5% of voters, narrowly passing the 55% threshold. By 23 May, preliminary referendum results were recognized by all five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, suggesting widespread international recognition if Montenegro were to become formally independent. On 31 May, the referendum commission officially confirmed the results of the referendum, verifying that 55.5% of the population of Montenegrin voters had voted in favor of independence.[2][3] Because voters met the controversial threshold requirement of 55% approval, the referendum was incorporated into a declaration of independence during a special parliamentary session on 31 May. The Assembly of the Republic of Montenegro made a formal Declaration of Independence on Saturday 3 June.[4]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Do you want the Republic of Montenegro to be an independent state with full international and legal personality? Montenegrin: Želite li da Republika Crna Gora bude nezavisna država sa punim međunarodno-pravnim subjektivitetom? | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Results | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

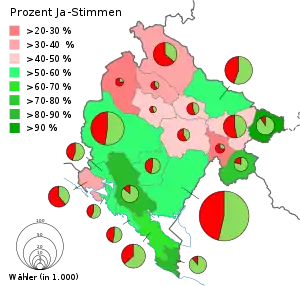

Results by council area | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Note: saturation of colour denotes strength of vote | ||||||||||||||||||||||

In response to the announcement, the government of Serbia declared itself the legal and political successor of Serbia and Montenegro,[5] and that the government and parliament of Serbia itself would soon adopt a new constitution.[6] The United States, China, Russia, and the institutions of the European Union all expressed their intentions to respect the referendum's results.

Constitutional background

The process of secession was regulated by the Constitutional Charter of Serbia and Montenegro adopted on 4 February 2003 by both Councils of the Federal Assembly of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, in accordance to the 2002 Belgrade Agreement between the governments of the two constitutive republics of the state then known as the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, Montenegro and Serbia. Article 60 of the constitution required that a minimum of three years pass after its ratification before one of the member states could declare independence. The same article specified the referendum as necessary for this move. However, this constitution allowed member states to define their own referendum laws.

It is also specified that the member state which secedes forfeits any rights to political and legal continuity of the federation. This means that the seceding state (in this case the Republic of Montenegro) had to apply for membership to all major international institutions, such as the United Nations and be recognized by the international community, and that the remaining state (in this case the Republic of Serbia) became the full successor to the state union. No state objected to recognizing a newly formed state prior to the referendum. If Serbia had declared independence instead of Montenegro, Montenegro would have been the legal successor state.

Legal procedure

According to the Montenegrin Constitution,[7] state status could not be changed without a referendum proposed by the President to the Parliament. The Law on the Referendum on State Legal Status was first submitted by President Filip Vujanović, and it was unanimously passed by the Montenegrin Parliament on 2 March 2006.[8] In addition to formulating the official question to be printed on the referendum ballot, the law also included a three-year moratorium on a repeat referendum, such that if the referendum results had rejected independence, another one could have been legally held in 2009.[9]

The Referendum Bill obliged the Parliament, which introduced the referendum, to respect its outcome. It had to declare the official results within 15 days following the voting day, and act upon them within 60 days. The dissolution of Parliament was required upon the passage of any bill proposing constitutional changes to the status of the state, and a new Parliament was required to convene within ninety days. For such changes to be enacted, the new Parliament was required to support the bill with a two-thirds majority.

The newly independent country of Serbia, which is the successor state to the state union of Serbia and Montenegro, while favoring a loose federation, stated publicly that it would respect the outcome of the referendum, and not interfere with Montenegrin sovereignty.

Controversies

There was considerable controversy over suffrage and needed result threshold for independence. The Montenegrin government, which supported the independence, initially advocated a simple majority, but the opposition insisted on a certain threshold below which the referendum, if a "yes" option won, would have been moot.

European Union envoy Miroslav Lajčák proposed independence if a 55% supermajority of votes are cast in favor with a minimum turnout of 50%, a determination that prompted some protests from the pro-independence forces. The Council of the European Union unanimously agreed to Lajčák's proposal, and the Đukanović government ultimately backed down in its opposition.[10] Milo Đukanović, Prime Minister of Montenegro, however, promised that he would declare independence if the votes passed 50%, regardless of whether the census was passed or not. On the other hand, he also announced that if less than 50% voted for the independence option, he would resign from all political positions.[11] The original pursuit of Milo Đukanović and the DPS-SDP was that 40% voting in favour of statehood be a sufficient percentage to declare independence, but this caused severe international outrage before the Independentists proposed 50%.

Another controversial issue was the referendum law, based on the constitution of Serbia and Montenegro, which stated that Montenegrins living within Serbia registered to vote within Serbia should be prohibited from voting in the referendum because that would give them two votes in the union and make them superior to other citizens. Also, the agreement threshold between the two blocs for 55%, was somewhat criticized as overriding the traditional practice of requiring a two-thirds supermajority, as practiced in all ex Yugoslav countries before (including the previous referendum in Montenegro).

Blocs

Pro-independence

- Democratic Party of Socialists (DPS)

- Social Democratic Party (SDP)

- Civic Party of Montenegro (GP)

- Liberal Party of Montenegro (LP)

- People's Concord of Montenegro (NSCG)

- Democratic Union of Albanians (DUA)

- Bosniak Party (BS)

- Croatian Civic Initiative (HGI)

A controversy emerged in the Independentist Bloc, as non-governmental organizations had officially joined and campaigned as its members, which was illegal, thus breaking the Law:

- Movement for Independent European Montenegro

- Civic Forum Nikšić

- Democratic Community of Muslims Bosniaks in Montenegro.

The pro-independence camp mainly concentrated on history and national minority rights. Montenegro was recognized an independent country in the 1878 Congress of Berlin. Its independence was extinguished in 1918 when its assembly declared union with Serbia. The minor ethnic groups are promised full rights in an independent Montenegro, with their languages being included into the new Constitution.

The camp's leader was Prime Minister of Montenegro Milo Đukanović.[12]

Pro-union

- Socialist People's Party (SNP)

- People's Party (NS)

- Democratic Serb Party (DSS)

- Serb People's Party (SNS)

- People's Socialist Party (NSS)

- Party of Serb Radicals (SSR)

The Unionists' campaign slogans were Montenegro is Not for Sale! and For Love - Love Connects, Heart says no!.

The Unionist Camp or "Bloc for Love", Together for Change political alliance's campaign relied mostly on the assertion and support of the European Union, and pointing out essential present and historical links with Serbia. They criticized that the ruling coalition was trying to turn Montenegro into a private state and a crime haven. Its campaign concentrated on pointing out "love" for union with Serbia. 73% of Montenegrin citizens had close cousins in Serbia and 78% of Montenegrin citizens had close friends in Serbia. According to TNS Medium GALLUP's research, 56.9% of the Montenegrin population believed if union with Serbia was broken, the health care system would fall apart. 56.8% believed they would not be able to go to schools in Serbia anymore and 65.3% thought it would not be able to find a job in Serbia as it intends to.

They used European Union flags, Slavic tricolors (which were also the official flag of the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro) and Serb Orthodox tricolors.

The key camp's leader was opposition leader Predrag Bulatović.[13]

Neutral

- Movement for Changes (PzP)

- Democratic League in Montenegro (DS)

- New Democratic Force (FORCA)

The Movement for Changes, although de facto supporting independence, decided not to join the pro-independence coalition, on the arguments that they considered the independentists as largely made of 'DPS criminals', and that the bloc is an "Unholy Alliance" gathered around a controversial Prime Minister Milo Đukanović, seen by these party officials as an obstacle to complete democracy in Montenegro.

A similar stance was taken by the ethnic Albanian Democratic League in Montenegro, which called the Albanians of Montenegro to boycott the referendum. Regardless, most ethnic Albanians voted for independence.

Opinion polling

Polling throughout the campaign was sporadic, with most polls showing pro-independence forces leading but not surpassing the 55% threshold. Only in the later weeks did polls begin to indicate the threshold would be passed, albeit barely.[14]

Results

| Choice | Votes | % |

|---|---|---|

| 230,711 | 55.50 | |

| 184,954 | 44.50 | |

| Required majority | 55 | |

| Valid votes | 415,665 | 99.15 |

| Invalid or blank votes | 3,571 | 0.85 |

| Total votes | 419,236 | 100.00 |

| Registered voters and turnout | 484,718 | 86.49 |

| Source: Nohlen & Stöver | ||

Two organisations that were conducting a quick count, Montenegrin CDT and Serbian CeSID, had different projections of the referendum results. CeSID's initial projections were giving the "yes" option significant advantage, but as the evening progressed, they changed their projection and lowered the advantage of the "yes" option. This caused serious confusion among general public and sparked journalists to challenge CeSID projections. After CeSID's announcement, thousands of people began to celebrate in the streets of every major city.[15] However, after the CDT announcement, the public began to realize how close the result was.

CDT stated that the results were too close to call. This was later confirmed with the official results, since only about 2,000 votes were over the required threshold (the votes of some 2 or 3 polling stations). They urged the public to remain calm and give time to the referendum commission to finish their job.[16]

Montenegrin prime minister Milo Đukanović first delayed his appearance in public, after learning how close the result was. He finally appeared on Montenegrin television at about 01:40 CEST and said that after 99.85% of the votes had been counted, the percentage of votes for independence was 55.5%, and the remaining votes (6,236) could not change the outcome of the referendum.[17]

On the other side, de facto leader of the unionist bloc Predrag Bulatović said at a press conference around 00:15 CEST that "his sources" informed him that 54% had voted "yes", a figure below the 55% threshold. Predrag Bulatović had announced earlier that he would resign as opposition leader if the referendum was won by those favouring independence.

František Lipka, the referendum commission president or Chairman of the Electoral Commission announced on Monday the 22 May 2006 that the preliminary results were 55.4% in favor of independence.[18] Prime Minister of the Republic of Montenegro Milo Đukanović held a press conference later that day. The press conference took place at 14:30, at the Congress Hall of the Government of the Republic of Montenegro.[19]

Because about 19,000 votes were still disputed, the Electoral Commission delayed the announcement of final results. The opposition demanded a full recount of the votes but this was rejected by the Commission and European observers, who stated that they were satisfied and they were sure that the vote had been free and fair.[20]

The distribution of votes was as follows: majority (around 60%-up to around 70%) were against independence in regions bordering Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. The highest No vote was in Serb-majority Plužine municipality with 75.70%. In the authentic Montenegrin regions (former Principality of Montenegro), there was a light majority (around 50-60%) for independence, with the Cetinje municipality, traditional centre of old Montenegro, having a huge percentage in favour of independence (over 86.38%). At the coastal regions, Herceg Novi municipality, which has a Serb majority had voted 61.34% against independence, the middle southern region (Tivat, Kotor, Budva and Bar) being in favour of independence, and the south, Ulcinj municipality, an ethnic Albanian centre, voted strongly in favour of independence (88.50%). The regions bordering Albania and Kosovo that have mostly Bosniak, ethnic Muslim and Albanian population, were heavily in favour of independence (78.92% in Plav, 91.33% in Rožaje). Municipalities in Montenegro that voted for the Union were Andrijevica, Berane, Kolašin, Mojkovac, Plužine, Pljevlja, Herceg-Novi, Šavnik, and Žabljak. The municipalities that voted for independence were Bar, Bijelo Polje, Budva, Cetinje, Danilovgrad, Kotor, Nikšić, Plav, Podgorica, Rožaje, Tivat, and Ulcinj.[3] The Independentist Bloc won thanks to the high votes of Albanians and to an extent Bosniaks. The highest pro-independence percentages were in Albanian-populated Ulcinj, Bosniak-populated Rožaje and Montenegrin Old Royal Capital Cetinje.[21]

| Municipality | Yes | Yes % | No | No % | Registered | Voted | Voted % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andrijevica | 1,084 | 27.6% | 2,824 | 71.89% | 4,369 | 3,928 | 89.91% |

| Bar | 16,640 | 63.07% | 9,496 | 35.99% | 32,255 | 26,382 | 81.79% |

| Berane | 11,268 | 46.85% | 12,618 | 52.46% | 28,342 | 24,051 | 84.86% |

| Bijelo Polje | 19,405 | 55.36% | 15,437 | 44.04% | 40,110 | 35,051 | 87.39% |

| Budva | 5,908 | 52.75% | 5,180 | 46.25% | 12,797 | 11,200 | 87.52% |

| Cetinje | 11,536 | 85.21% | 1,818 | 13.43% | 15,077 | 13,538 | 89.79% |

| Danilovgrad | 5,671 | 53.15% | 4,887 | 45.81% | 11,784 | 10,669 | 90.54% |

| Herceg-Novi | 7,741 | 38.28% | 12,284 | 60.75% | 24,487 | 20,220 | 88.50% |

| Kolašin | 2,852 | 41.82% | 3,903 | 57.23% | 7,405 | 6,820 | 92.1% |

| Kotor | 8,200 | 55.04% | 6,523 | 43.79% | 17,778 | 14,897 | 83.79% |

| Mojkovac | 3,016 | 43.55% | 3,849 | 55.57% | 7,645 | 6,926 | 90.59% |

| Nikšić | 26,387 | 52.01% | 23,837 | 46.98% | 56,461 | 50,737 | 89.86% |

| Plav | 7,016 | 78.47% | 1,874 | 20.96% | 12,662 | 8,941 | 70.61% |

| Plužine | 716 | 24.2% | 2,230 | 75.36% | 3,329 | 2,959 | 88.88% |

| Pljevlja | 9,115 | 36.07% | 16,009 | 63.36% | 27,882 | 25,268 | 90.62% |

| Podgorica | 60,626 | 53.22% | 52,345 | 45.95% | 129,083 | 113,915 | 88.25% |

| Rožaje | 13,835 | 90.79% | 1,314 | 8.62% | 19,646 | 15,239 | 77.57% |

| Šavnik | 906 | 42.67% | 1,197 | 56.38% | 2,306 | 2,123 | 92.06% |

| Tivat | 4,916 | 55.86% | 3,793 | 43.1% | 10,776 | 8,800 | 81.66% |

| Ulcinj | 12,256 | 87.64% | 1,592 | 11.38% | 17,117 | 13,985 | 81.7% |

| Žabljak | 1,188 | 38.37% | 1,884 | 60.85% | 3,407 | 3,096 | 90.87% |

International reactions

On May 22, Croatian President Stipe Mesić sent a message of congratulations to Montenegro on its vote for independence. Mesić was the first foreign head of state to react officially to the vote.

The EU's foreign policy chief, Javier Solana, congratulated Montenegro on a "successful referendum" and said the turnout of over 86 percent "confirms the legitimacy of the process." The European Union would, he said, "fully respect" the final result.[22] The EU's commissioner for enlargement, Olli Rehn, said the European Union would put forward proposals for fresh talks with both Montenegro and Serbia. "All sides should respect the result and work together in order to build consensus on the basis of the acceptance of European values and standards. I now expect Belgrade and Podgorica to engage in direct talks on the practical implementation of the results".[23]

In a statement of 23 May, the United States affirmed the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE)/ODIHR assessment of the referendum, which stated that "the referendum was conducted in line with OSCE and Council of Europe commitments and other international standards for democratic electoral processes." The United States said "We urge Montenegro and Serbia to work together to resolve the practical issues necessary to implement the will of the people of Montenegro as expressed in the referendum."[24]

The Russian Foreign Ministry issued a statement on 23 May stating "It is of fundamental importance for Montenegro and Serbia to enter into constructive, friendly and comprehensive dialogue with the aim of producing mutually acceptable political solutions regarding their future relations," the Foreign Ministry said.[25]

The UK's Europe Minister Geoff Hoon said he was pleased that the referendum had complied with international standards, pointing out that "the people of Montenegro have expressed a clear desire for an independent state."[26]

A spokesperson for the Chinese foreign ministry indicated that "China respects the choice of people of Montenegro and the final result of the referendum" in a regularly scheduled news conference on 23 May.[27]

The unanimous recognition of the referendum result by the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council indicated that widespread international recognition of Montenegro would likely be swift once independence was formally declared.

Serbian reactions

Serbian president Boris Tadić accepted the results of the referendum in favor of independence, while Serbian prime minister Vojislav Koštunica, a firm opponent of Montenegrin independence, resolved to wait until the end of the week, so that the pro-union Montenegrin opposition would have time to challenge the final verdict.[28]

The prime minister of Kosovo, Agim Çeku, announced that Kosovo would follow Montenegro in the quest for independence, saying "This is the last act of the historic liquidation of Yugoslavia /.../ this year Kosovo will follow in Montenegro's footsteps." Kosovo declared its state's own independence on 17 February 2008, but is still seen in Serbian nationalism as the historical and spiritual heart of Serbia.[29]

Ethnic Serb groups in neighbouring Bosnia and Herzegovina planned to demand a referendum on the independence of the Republika Srpska, according to the Croatian daily Večernji list, citing Branislav Dukić, leader of Spona, a regional Serb organisation.[30] Since such a move could start another war in Bosnia, it provoked widespread condemnation from the United States, European Union, and other nations. Milorad Dodik, the prime minister of Republika Srpska, subsequently withdrew his calls for a referendum, citing international opposition and the fact that such a referendum would violate the Dayton peace agreement.[31]

Conduct and international influence

Irregularities

On 24 March 2006, a nine-minute video clip was aired that shows two local Democratic Party of Socialists of Montenegro activists from Zeta region, Ranko Vučinić and Ivan Ivanović, along with a former member of secret police, Vasilije Mijović, attempting to bribe a citizen, Mašan Bušković, into casting a pro-independence vote at the upcoming referendum.[32] In the video clip they are seen and heard persuading Bušković to vote for the independence, promising to pay off his electric bill of €1,580 in return.[33] When the video was publicized, two DPS activists claimed they were victims of manipulation and that Vasilije Mijović talked them into doing so. Mijović denied those claims saying the video had been authentic. DPS spokesperson Predrag Sekulić claimed the video was "a montage" and "a cheap political setup." Mašan Bušković, the target of the alleged attempted bribe, on the other hand said the video is authentic and that it portrays events exactly as they occurred.[34]

Public workers, such as teachers and police officers, were subject to pressure from their employers to vote for independence.[35] The DPS chief whip, Miodrag Vuković, alluded to this in May 2006 when he said one "cannot work for the state and vote against it".[35]

In 2007, Jovan Markuš with the help of unionist parties published a 1,290-page document called Bijela Knjiga ("White Book"), recording irregularities from the referendum.[36]

International lobby

.jpg.webp) |  |

| Milan Roćen | Oleg Deripaska |

According to an investigation supported by the Puffin Foundation Investigative Fund in 2008, The Nation reported that Milan Roćen authorized a contract with Davis Manafort Inc, a consulting firm founded by Rick Davis, and that the firm was paid several million dollars to help organize the independence campaign.[37] Election finance documents did not record any exchanges with Davis Manafort, although the claims of the payments were backed by multiple American diplomats and Montenegrin government officials on the condition of anonymity.[37]

In early May 2006, Davis invited Nathaniel Rothschild to participate in the campaign after the unionist bloc suggested Montenegrin students studying in Serbia would lose scholarship benefits if Montenegro were to secede.

Rothschild promised to commit $1 million to Montenegrin students studying in Serbia if they were to lose their scholarship benefits in the event of Montenegrin secession.[37]

Almost a decade later, Paul Manafort revealed during his trials that he had been hired by Oleg Deripaska to support the referendum in Montenegro.[38] In a discussion with Radio Free Europe in 2017, Branko Lukovac, a former campaign chief for the independence bloc, claimed that he was not aware of a contract with Manafort, but acknowledged the following:

"We in America had especially strong support and a group of friends on top with former presidential candidate Bob Dole, who contributed in Congress, Senate, State Department, and further circles, we even had access to Colin Powell...to support our movement to independence."[39]

Dole had been paid a sum of $1.38 million by the Montenegrin government for lobbying between 2001 and 2008.[37] Lukovac denied any contract with either Manafort or Deripaska, claiming that Russian President Vladimir Putin told his campaign that "he'd prefer to for us to stay in the state union Serbia and Montenegro rather than separate, but if that is what is democratically defined by the majority of Montenegrin citizens, that they [Russia] would support that."[39]

In June 2019, an audio recording from the mid-2005 surfaced, that shows then ambassador of the Serbia and Montenegro to the Russian Federation Milan Roćen, expresses concern over the EU pressure on the authorities of the Republic of Montenegro, asking Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska, on behalf of then-Prime Minister of Montenegro Đukanović, to lobby for the 2006 Montenegrin independence referendum, through his connections with Canadian billionaire Peter Munk in the United States.[40]

Notes

- Nohlen, D & Stöver, P (2010) Elections in Europe: A data handbook, p1372 ISBN 978-3-8329-5609-7

- Referendum Commission of Montenegro at the Wayback Machine (archive index)

- Electoral Commission official press release at the Wayback Machine (archive index)

- Montenegro declares independence BBC News, 4 June 2006

- Serbian Press Release Government of Serbia

- Press Release

- Constitution of the Republic of Montenegro at the Wayback Machine (archive index)

- "Referendum 21. Maja" (in Serbian). B92. March 2, 2006.

- Morrison 2009, p. 206.

- EUobserver: EU wins Montenegro's support for its referendum formula (subscription needed)

- Council on Foreign Relations: Montenegro's Referendum on Independence Archived 2007-10-04 at the Wayback Machine

- "Crna Gora nezavisna do maja 2006", B92

- Referendum u devet slika, Vreme

- EUobserver: EU awaits Montenegro independence vote (subscription needed)

- DTT-NET: Montenegro government claims independence victory Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Centar za demokratsku tranziciju - Referendum archived on 9 June 2007 from the original

- CNN: Poll: Montenegro quits Serbia Archived 2006-06-29 at the Wayback Machine

- AP: Montenegro Votes to Secede from Serbia

- "Prime Minister of Montenegro". Vlada.me. Retrieved 2011-01-16.

- BBC: Recount call in Montenegro vote

- Balkan Update: Albanian and Bosniacs make Montenegro independent Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Radio Free Europe: "Montenegrins Close To Independence"

- EUobserver: EU prepares for separate accession of sovereign Montenegro (subscription needed)

- "US Statement on the Montenegrin Referendum on State Status". Vlada.me. Retrieved 2011-01-16.

- "Moscow respects choice of Montenegro's people". Vlada.me. Retrieved 2011-01-16.

- GNN: "Minister for Europe Geoff Hoon MP welcomes Montenegro referendum result" Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine (23 May 2006)

- "Foreign Ministry Spokesman Liu Jianchao's Regular Press Conference on 23 May 2006". Fmprc.gov.cn. Retrieved 2011-01-16.

- DTT-NET: "Serbia's president recognises Montenegro referendum results, PM waiting" Archived 2011-07-19 at the Wayback Machine

- EUobserver: "EU prepares for separate accession of sovereign Montenegro"

- Vecernji list: Reakcije Republika Srpska nakon crnogorskog referenduma

- AKI: Bosnia: Serb leader assures "no revolution" over Kosovo

- Petar Komnenić (April 3, 2006). "Kako je Mašan postao zvijezda..." (in Serbian). Radio Free Europe. Retrieved June 3, 2018.

- Morrison 2009, p. 208.

- RTS: Opozicija prikazala film o kupovini glasova

- Morrison 2009, p. 210.

- Veliša KADIĆ - Savo GREGOVIĆ (May 17, 2016). "Pokolenja će da sude" (in Serbian). Večernje novosti. Retrieved February 10, 2019.

- Mark Ames, Ari Berman (October 1, 2008). "McCain's Kremlin Ties". The Nation. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- Dušica Tomović (April 12, 2017). "Trump Campaign Chief 'Worked for Montenegrin Independence'". Balkan Insight. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- Srđan Janković (October 31, 2017). "Trampov Manafort i nezavisnost crnogorska" (in Serbian). Radio Free Europe. Retrieved April 15, 2019.

- Molio Deripasku da lobira za referendum, Dan (newspaper), 22 June 2019

References

- Morrison, Kenneth (2009). Nationalism, Identity and Statehood in Post-Yugoslav Montenegro. London: I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84511-710-8.

External links

- Unionist Bloc video: Vote for Love!

- Unionist Bloc theme: Love connects

- BBC: Page on the subject

- BBC: Post-election coverage

- Referendum Law (PDF)

- The Njegoskij Fund Public Project >> 21 May 2006 Referendum on Independence