Protea comptonii

Protea comptonii, also known as saddleback sugarbush,[1][2][4][5][6] is a smallish tree[5][6] of the genus Protea in the family Proteaceae.[1][4] It is found in South Africa and Eswatini.[1][7]

| Protea comptonii | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Protea comptonii | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Proteales |

| Family: | Proteaceae |

| Genus: | Protea |

| Species: | P. comptonii |

| Binomial name | |

| Protea comptonii | |

Names

Other vernacular names which have been recorded to be used for this species in South Africa are Barberton Mountain sugarbush and Barberton sugarbush.[1][2] A name recorded in Eswatini is mountain protea.[8] In the Afrikaans language the names Barberton-suikerbos,[1][6] Barbertonse bergsuikerbos or Compton-se-suikerbos are used.[1] In the siSwati language the name sicalabane has been recorded[7][8] -this name is used for a great many other of the larger proteas.[8] Another name used for the tree in this language is sidlungu,[7][8] although that means 'protea' in general.[8]

Taxonomy

Protea comptonii was first described as a new species by John Stanley Beard in 1958.[3]

Classification

P. comptonii was classified in Protea section Patentiflorae by Tony Rebelo in 1995, what he calls the "mountain sugarbushes", along with P. angolensis, P. curvata, P. laetans, P. madiensis and P. rubropilosa. The validity of this group is suspect.[5]

Etymology

The specific epithet is an eponym commemorating the South African botanist Robert Harold Compton, who (among other pursuits) spent much of his career working on the flora of Eswatini.[9]

Description

This plant is a smallish tree, 4–8 metres (13–26 ft) tall, with a rounded, open crown and a trunk up to 50 centimetres (20 in) in diameter. The thick, corky bark is coloured grey, it forms a layer up to 20 centimetres (7.9 in) thick.[5] It is a long-lived species with a generation length of 50 to 100 years.[1]

The inflorescences are specialised structures called pseudanthia, also known simply as flower heads, containing hundred of reduced flowers, called florets. The flower heads are surrounded by 'involucral bracts'; these bracts are cream-coloured and glabrous. Together with Protea curvata and P. rubropilosa this species has a large receptacle at the base of the flower head which has a dome-shape – this is thought to be a more basal evolutionary characteristic. The style is 65 to 80mm in length.[5]

Distribution

In South Africa this plant occurs in two disjunct populations in the provinces of Mpumalanga (eastern) and KwaZulu-Natal (northern).[1][2][10] The KwaZulu-Natal range is restricted to the hills around the town of Vryheid and the Ithala Game Reserve[1][2] in the eNgotshe region around the town of Louwsburg,[2] but as of 2019 it has become extirpated from the Vryheid hills.[1] The Mpumalanga population spills over into Eswatini, where the tree grows only in the far northwest -this population is found in the hills south of the town of Barberton[2][1][7] and southeast from Kaapsehoop,[2] an old gold rush town -an ancient land with very special ultramafic soil. Protea curvata also occurs here.

In Eswatini this tree is only found near the town of Bulembu (2001)[11][12] and in the Malolotja National Park.[7][11][12]

The present spatial distribution of the species is fragmented into smaller subpopulations, most of these are very small, but historically it was much more common and formed large groves on grassland in the Barberton mountains. The remaining habitat is largely grassland fragments between timber plantations.[1] Where it does still occur it is often the dominant plant, forming almost pure stands.[2]

Ecology

This species is found growing in a limited number of specific habitats: montane grassland around Barberton, and in KwaZulu-Natal it occurs in either sourveld or grassland in the Zululand mistbelt, on quartzite-derived substrates.[1] It is found on steep, south-facing slopes among quartzite outcrops,[1][2] at altitudes of 700 to 1,800 metres.[1]

The tree blooms in the winter in the Barberton mountains.[4] Pollination is achieved by means of visits by nectar-feeding birds. Its aerial stems can survive the wildfires which periodically pass through its habitat and re-sprout.[1]

Its seeds are not stored on the plant as are those of many other proteas, and are released from the infructescence immediately after ripening. The seeds are dispersed by action of the wind.[1] Recruitment appears to occur at a low rate.[2]

Cattle do not feed on the leaves of this tree, or at least leave it alone in the veld, but it is consumed by wild antelope.[1]

Uses

There are no recorded uses known in Eswatini.[8] According to the IUCN the bark is used in traditional medicine by locals.[2]

Conservation

Legislation

It is the only Protea species protected in South Africa under the National Forests Act of 1998. Pursuant to this law, plants may not be disturbed, damaged or destroyed in any way, nor may their products be possessed, collected, transported, purchased or sold, except under licence granted by the relevant delegated provincial authority.[6]

In Eswatini the species is legally protected under the Flora Protection Act of 2000, being classified as an 'endangered' species in the 2002 Southern African Plant Red Data List by the Southern African Botanical Diversity Network, it was afforded 'Schedule A' protection;[13] it is unclear if that has changed now the conservation status has been downgraded.

Population

It was formerly common in the Barberton Mountains.[1] In 1998 the IUCN believed that the total population was somewhat declining in number and range.[2] According to the South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI), in 2019 the entire world population only consisted of some 3,150 to 6,300 individual plants in the wild, and was still believed to be decreasing. Most of the known different subpopulations consist of fewer than 200 plants. There are an estimated 2000-5000 plants in Mpumalanga, the largest population in Songimvelo has several hundred plants. The Ithala Nature Reserve is thought to contain almost all, if not all, of the plants in KwaZulu-Natal, a total of 1100 mature individuals divided over five to eight small subpopulations of 30-180 plants; the numbers of the plants are monitored here, and there is continuing decline. It is estimated that there are around 200 plants in Swaziland divided over three localities. It is inferred from the extent of habitat loss that the population has been reduced by 23-28% over the past 150 to 300 years.[1]

Status

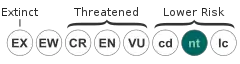

The conservation status of Protea comptonii was first assessed in the 1980 book Threatened plants of southern Africa as 'rare'. In 1996 the South African National Botanical Institute, later the Biodiversity Institute, rated the status as 'vulnerable' in the Red data list of southern African plants.[1] In 1998 the IUCN assessed the global status of the species for their Red List as 'lower risk/near threatened'.[2] An assessment of 'vulnerable' was given in 1999 by the KwaZulu-Natal Nature Conservation Service for the population in that province. SANBI re-assessed the species in 2009, downgrading the status to 'near threatened', but in 2019, in a new assessment, it upgraded the status again to 'vulnerable'.[1]

Threats

Historically much of its habitat in the mountains around Barberton was destroyed and fragmented in order to plant forests for timber exploitation, and at present, some 26% of the habitat has been irreversibly modified, mainly in this region. However, loss of range to afforestation is no longer occurring.[1] According to the IUCN in 1998, the main threats to the survival of P. comptonii were the harvesting of the bark for herbalism and unsustainable browsing by native herbivores (game).[2] As of 2019 game remains an important problem in Ithala. Although P. comptonii is not directly affected, in Songimvelo overgrazing by livestock is causing the grasslands to degrade and encouraging the spread of invasive plants. The plants which do not occur in protected areas in Mpumalanga grow on land owned by commercial forestry companies or mines, and as 2019 there is some renewed interest in exploiting the mineral wealth of the region, which might constitute a future threat, at least for two subpopulations.[1]

The species is unable to recover from too frequent burning.[2] In Ithala biennial burns are likely to be causing a decline in numbers and ongoing habitat degradation.[1]

In Eswatini threats identified are competition from invasive plants, too frequent fires and habitat loss due to mining.[1]

Protected areas

Most extant wild individuals of this species are restricted to protected areas, namely Songimvelo Game Reserve (which contains the largest numbers) and Barberton Nature Reserve in Mpumalanga,[1] and in KwaZulu-Natal the Ithala Game Reserve.[1][2] The population in Eswatini is largely protected within the Malolotja National Park.[7][11][12]

References

- Rebelo, A.G.; Mtshali, H.; von Staden, L. (19 August 2019). "Saddleback Sugarbush". Red List of South African Plants. version 2020.1. South African National Biodiversity Institute. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- Hilton-Taylor, C.; et al. (1 January 1998). "Protea comptonii". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1998: e.T30355A9539680. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1998.RLTS.T30355A9539680.en.

- "Protea comptonii". International Plant Names Index. The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Harvard University Herbaria & Libraries and Australian National Botanic Gardens. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- "Protea comptonii (Saddleback sugarbush)". Biodiversity Explorer. Iziko - Museums of South Africa. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- "Identifying Sugarbushes - Protea". Protea Atlas Project Website. 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- "Protected Trees" (PDF). Department of Water Affairs and Forestry, Republic of South Africa. 30 June 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2010.

- "Protea comptonii". Eswatini's Flora Database. Eswatini National Trust Commission. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- Long, Chris (December 2005). "PROTEACEAE". Eswatini's Flora - siSwati Names and Uses. Eswatini National Trust Commission. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- Dobson-Lofler, Linda (2005). "Background". Eswatini Tree Atlas. Eswatini National Trust Commission. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- "Protea comptonii Beard". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- "Malolotja Nature Reserve: Flora - Priority Species". Eswatini National Trust Commission. 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- "Eswatini's Flora Red List". Eswatini National Trust Commission. January 2011. Retrieved 14 September 2020.

- "Swaziland's Threatened Flora". Eswatini National Trust Commission. August 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2020.