Quantum error correction

Quantum error correction (QEC) is used in quantum computing to protect quantum information from errors due to decoherence and other quantum noise. Quantum error correction is essential if one is to achieve fault-tolerant quantum computation that can deal not only with noise on stored quantum information, but also with faulty quantum gates, faulty quantum preparation, and faulty measurements.

Classical error correction employs redundancy. The simplest way is to store the information multiple times, and—if these copies are later found to disagree—just take a majority vote; e.g. suppose we copy a bit three times. Suppose further that a noisy error corrupts the three-bit state so that one bit is equal to zero but the other two are equal to one. If we assume that noisy errors are independent and occur with some probability p, it is most likely that the error is a single-bit error and the transmitted message is three ones. It is possible that a double-bit error occurs and the transmitted message is equal to three zeros, but this outcome is less likely than the above outcome.

Copying quantum information is not possible due to the no-cloning theorem. This theorem seems to present an obstacle to formulating a theory of quantum error correction. But it is possible to spread the information of one qubit onto a highly entangled state of several (physical) qubits. Peter Shor first discovered this method of formulating a quantum error correcting code by storing the information of one qubit onto a highly entangled state of nine qubits. A quantum error correcting code protects quantum information against errors of a limited form.

Classical error correcting codes use a syndrome measurement to diagnose which error corrupts an encoded state. It then can reverse an error by applying a corrective operation based on the syndrome. Quantum error correction also employs syndrome measurements. It performs a multi-qubit measurement that does not disturb the quantum information in the encoded state but retrieves information about the error. A syndrome measurement can determine whether a qubit has been corrupted, and if so, which one. What's more, the outcome of this operation (the syndrome) tells us not only which physical qubit was affected but also in which of several possible ways it was affected. The latter is counter-intuitive at first sight: Since noise is arbitrary, how can the effect of noise be one of only few distinct possibilities? In most codes, the effect is either a bit flip, or a sign (of the phase) flip, or both (corresponding to the Pauli matrices X, Z, and Y). The reason is that the measurement of the syndrome has the projective effect of a quantum measurement. So even if the error due to the noise was arbitrary, it can be expressed as a superposition of basis operations—the error basis (which is here given by the Pauli matrices and the identity). The syndrome measurement "forces" the qubit to "decide" for a certain specific "Pauli error" to "have happened", and the syndrome tells us which, so that error correction can let the same Pauli operator act again on the corrupted qubit to revert the effect of the error.

The syndrome measurement tells us as much as possible about the error that has happened, but nothing at all about the value that is stored in the logical qubit—as otherwise the measurement would destroy any quantum superposition of this logical qubit with other qubits in the quantum computer, which would prevent it from being used to convey quantum information.

The bit flip code

The repetition code works in a classical channel, because classical bits are easy to measure and to repeat. This stops being the case for a quantum channel in which, due to the no-cloning theorem, it is no longer possible to repeat a single qubit three times. To overcome this, a different method first proposed by Asher Peres in 1985 [1] , such as the so-called three-qubit bit flip code, has to be used. This technique uses entanglement and syndrome measurements and is comparable in performance with the repetition code.

Consider the situation in which we want to transmit the state of a single qubit through a noisy channel . Let us moreover assume that this channel either flips the state of the qubit, with probability , or leaves it unchanged. The action of on a general input can therefore be written as .

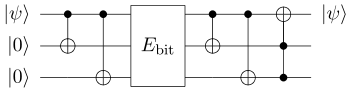

Let be the quantum state to be transmitted. With no error correcting protocol in place, the transmitted state will be correctly transmitted with probability . We can however improve on this number by encoding the state into a greater number of qubits, in such a way that errors in the corresponding logical qubits can be detected and corrected. In the case of the simple three-qubit repetition code, the encoding consists in the mappings and . The input state is encoded into the state . This mapping can be realized for example using two CNOT gates, entangling the system with two ancillary qubits initialized in the state .[2] The encoded state is what is now passed through the noisy channel.

The channel acts on by flipping some subset (possibly empty) of its qubits. No qubit is flipped with probability , a single qubit is flipped with probability , two qubits are flipped with probability , and all three qubits are flipped with probability . Note that a further assumption about the channel is made here: we assume that acts equally and independently on each of the three qubits in which the state is now encoded. The problem is now how to detect and correct such errors, without at the same time corrupting the transmitted state.

Let us assume for simplicity that is small enough that the probability of more than a single qubit being flipped is negligible. One can then detect whether a qubit was flipped, without also querying for the values being transmitted, by asking whether one of the qubits differs from the others. This amounts to performing a measurement with four different outcomes, corresponding to the following four projective measurements:

This can be achieved for example by measuring and then . This reveals which qubits are different from which others, without at the same time giving information about the state of the qubits themselves. If the outcome corresponding to is obtained, no correction is applied, while if the outcome corresponding to is observed, then the Pauli X gate is applied to the -th qubit. Formally, this correcting procedure corresponds to the application of the following map to the output of the channel:

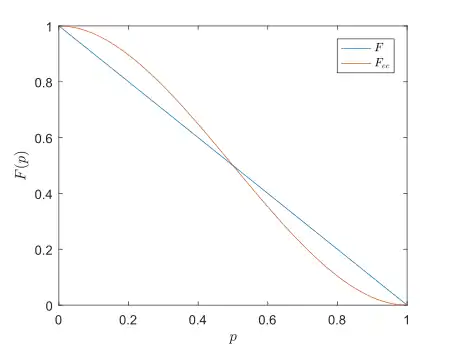

Note that, while this procedure perfectly corrects the output when zero or one flips are introduced by the channel, if more than one qubit is flipped then the output is not properly corrected. For example, if the first and second qubits are flipped, then the syndrome measurement gives the outcome , and the third qubit is flipped, instead of the first two. To assess the performance of this error correcting scheme for a general input we can study the fidelity between the input and the output . Being the output state correct when no more than one qubit is flipped, which happens with probability , we can write it as , where the dots denote components of resulting from errors not properly corrected by the protocol. It follows that

This fidelity is to be compared with the corresponding fidelity obtained when no error correcting protocol is used, which was shown before to equal . A little algebra then shows that the fidelity after error correction is greater than the one without for . Note that this is consistent with the working assumption that was made while deriving the protocol (of being small enough).

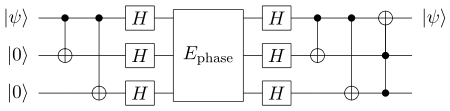

The sign flip code

Flipped bits are the only kind of error in classical computer, but there is another possibility of an error with quantum computers, the sign flip. Through the transmission in a channel the relative sign between and can become inverted. For instance, a qubit in the state may have its sign flip to

The original state of the qubit

will be changed into the state

In the Hadamard basis, bit flips become sign flips and sign flips become bit flips. Let be a quantum channel that can cause at most one phase flip. Then the bit flip code from above can recover by transforming into the Hadamard basis before and after transmission through .

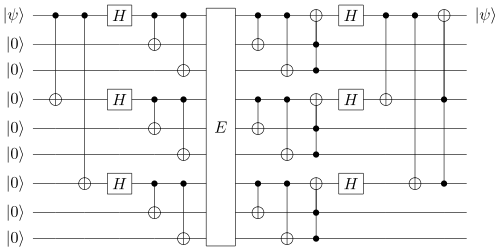

The Shor code

The error channel may induce either a bit flip, a sign flip (i.e., a phase flip), or both. It is possible to correct for both types of errors using one code, and the Shor code does just that. In fact, the Shor code corrects arbitrary single-qubit errors.

Let be a quantum channel that can arbitrarily corrupt a single qubit. The 1st, 4th and 7th qubits are for the sign flip code, while the three group of qubits (1,2,3), (4,5,6), and (7,8,9) are designed for the bit flip code. With the Shor code, a qubit state will be transformed into the product of 9 qubits , where

If a bit flip error happens to a qubit, the syndrome analysis will be performed on each set of states (1,2,3), (4,5,6), and (7,8,9), then correct the error.

If the three bit flip group (1,2,3), (4,5,6), and (7,8,9) are considered as three inputs, then the Shor code circuit can be reduced as a sign flip code. This means that the Shor code can also repair sign flip error for a single qubit.[3]

The Shor code also can correct for any arbitrary errors (both bit flip and sign flip) to a single qubit. If an error is modeled by a unitary transform U, which will act on a qubit , then can be described in the form

where ,,, and are complex constants, I is the identity, and the Pauli matrices are given by

If U is equal to I, then no error occurs. If , a bit flip error occurs. If , a sign flip error occurs. If then both a bit flip error and a sign flip error occur. Due to linearity, it follows that the Shor code can correct arbitrary 1-qubit errors.

Bosonic codes

Several proposals have been made for storing error-correctable quantum information in bosonic modes. Unlike a two-level system, a quantum harmonic oscillator has infinitely many energy levels in a single physical system. Codes for these systems include cat,[4][5][6] Gottesman-Kitaev-Preskill (GKP),[7] and binomial codes.[8][9] One insight offered by these codes is to take advantage of the redundancy within a single system, rather than to duplicate many two-level qubits.

Written in the Fock basis, the simplest binomial encoding is

where the subscript L indicates a "logically encoded" state. Then if the dominant error mechanism of the system is the stochastic application of the bosonic lowering operator the corresponding error states are and respectively. Since the codewords involve only even photon number, and the error states involve only odd photon number, errors can be detected by measuring the photon number parity of the system.[8][10] Measuring the odd parity will allow correction by application of an appropriate unitary operation without knowledge of the specific logical state of the qubit. However, the particular binomial code above is not robust to two-photon loss.

General codes

In general, a quantum code for a quantum channel is a subspace , where is the state Hilbert space, such that there exists another quantum channel with

where is the orthogonal projection onto . Here is known as the correction operation.

A non-degenerate code is one for which different elements of the set of correctable errors produce linearly independent results when applied to elements of the code. If distinct of the set of correctable errors produce orthogonal results, the code is considered pure.[11]

Models

Over time, researchers have come up with several codes:

- Peter Shor's 9-qubit-code, a.k.a. the Shor code, encodes 1 logical qubit in 9 physical qubits and can correct for arbitrary errors in a single qubit.

- Andrew Steane found a code which does the same with 7 instead of 9 qubits, see Steane code.

- Raymond Laflamme and collaborators found a class of 5-qubit codes which do the same, which also have the property of being fault-tolerant. A 5-qubit code is the smallest possible code which protects a single logical qubit against single-qubit errors.

- A generalisation of the technique used by Steane, to develop the 7-qubit code from the classical [7, 4] Hamming code, led to the construction of an important class of codes called the CSS codes, named for their inventors: A. R. Calderbank, Peter Shor and Andrew Steane. According to the quantum Hamming bound, encoding a single logical qubit and providing for arbitrary error correction in a single qubit requires a minimum of 5 physical qubits.

- A more general class of codes (encompassing the former) are the stabilizer codes discovered by Daniel Gottesman (), and by A. R. Calderbank, Eric Rains, Peter Shor, and N. J. A. Sloane (, ); these are also called additive codes.

- Two dimensional Bacon-Shor codes are a family of codes parameterized by integers m and n. There are nm qubits arranged in a square lattice.[12]

- A newer idea is Alexei Kitaev's topological quantum codes and the more general idea of a topological quantum computer.

- Todd Brun, Igor Devetak, and Min-Hsiu Hsieh also constructed the entanglement-assisted stabilizer formalism as an extension of the standard stabilizer formalism that incorporates quantum entanglement shared between a sender and a receiver.

That these codes allow indeed for quantum computations of arbitrary length is the content of the quantum threshold theorem, found by Michael Ben-Or and Dorit Aharonov, which asserts that you can correct for all errors if you concatenate quantum codes such as the CSS codes—i.e. re-encode each logical qubit by the same code again, and so on, on logarithmically many levels—provided the error rate of individual quantum gates is below a certain threshold; as otherwise, the attempts to measure the syndrome and correct the errors would introduce more new errors than they correct for.

As of late 2004, estimates for this threshold indicate that it could be as high as 1-3%,[13] provided that there are sufficiently many qubits available.

Experimental realization

There have been several experimental realizations of CSS-based codes. The first demonstration was with NMR qubits.[14] Subsequently, demonstrations have been made with linear optics,[15] trapped ions,[16][17] and superconducting (transmon) qubits.[18]

In 2016 for the first time the lifetime of a quantum bit was prolonged by employing a QEC code.[19] The error-correction demonstration was performed on Schrodinger-cat states encoded in a superconducting resonator, and employed a quantum controller capable of performing real-time feedback operations including read-out of the quantum information, its analysis, and the correction of its detected errors. The work demonstrated how the quantum-error-corrected system reaches the break-even point at which the lifetime of a logical qubit exceeds the lifetime of the underlying constituents of the system (the physical qubits).

Other error correcting codes have also been implemented, such as one aimed at correcting for photon loss, the dominant error source in photonic qubit schemes.[20][21]

See also

References

- Peres, Asher (1985). "SReversible Logic and Quantum Compzters". Physical Review A. 32 (6): 3266–3276. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.32.3266.

- Michael A. Nielsen and Isaac L. Chuang (2000). Quantum Computation and Quantum Information. Cambridge University Press.

- W.Shor, Peter (1995). "Scheme for reducing decoherence in quantum computer memory". Physical Review A. 52 (4): R2493–R2496. Bibcode:1995PhRvA..52.2493S. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.52.R2493. PMID 9912632.

- Cochrane, P. T.; Milburn, G. J.; Munro, W. J. (1999-04-01). "Macroscopically distinct quantum-superposition states as a bosonic code for amplitude damping". Physical Review A. 59 (4): 2631–2634. arXiv:quant-ph/9809037. Bibcode:1999PhRvA..59.2631C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.59.2631. S2CID 119532538.

- Leghtas, Zaki; Kirchmair, Gerhard; Vlastakis, Brian; Schoelkopf, Robert J.; Devoret, Michel H.; Mirrahimi, Mazyar (2013-09-20). "Hardware-Efficient Autonomous Quantum Memory Protection". Physical Review Letters. 111 (12): 120501. arXiv:1207.0679. Bibcode:2013PhRvL.111l0501L. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.111.120501. ISSN 0031-9007. PMID 24093235. S2CID 19929020.

- Mirrahimi, Mazyar; Leghtas, Zaki; Albert, Victor V; Touzard, Steven; Schoelkopf, Robert J; Jiang, Liang; Devoret, Michel H (2014-04-22). "Dynamically protected cat-qubits: a new paradigm for universal quantum computation". New Journal of Physics. 16 (4): 045014. arXiv:1312.2017. Bibcode:2014NJPh...16d5014M. doi:10.1088/1367-2630/16/4/045014. ISSN 1367-2630. S2CID 7179816.

- Daniel Gottesman, Alexei Kitaev, John Preskill (2001). "Encoding a qubit in an oscillator". Physical Review A. 64 (1): 012310. arXiv:quant-ph/0008040. Bibcode:2001PhRvA..64a2310G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.64.012310. S2CID 18995200.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Michael, Marios H.; Silveri, Matti; Brierley, R. T.; Albert, Victor V.; Salmilehto, Juha; Jiang, Liang; Girvin, S. M. (2016-07-14). "New Class of Quantum Error-Correcting Codes for a Bosonic Mode". Physical Review X. 6 (3): 031006. arXiv:1602.00008. Bibcode:2016PhRvX...6c1006M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.6.031006. S2CID 29518512.

- Victor V. Albert; et al. (2018). "Performance and structure of single-mode bosonic codes". Physical Review A. 97 (3): 032346. arXiv:1708.05010. Bibcode:2018PhRvA..97c2346A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.97.032346. S2CID 51691343.

- Sun, L.; Petrenko, A.; Leghtas, Z.; Vlastakis, B.; Kirchmair, G.; Sliwa, K. M.; Narla, A.; Hatridge, M.; Shankar, S.; Blumoff, J.; Frunzio, L. (July 2014). "Tracking photon jumps with repeated quantum non-demolition parity measurements". Nature. 511 (7510): 444–448. arXiv:1311.2534. doi:10.1038/nature13436. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 25043007. S2CID 987945.

- Calderbank, A. R.; Rains, E. M.; Shor, P. W.; Sloane, N. J. A. (1998). "Quantum Error Correction via Codes over GF(4)". IEEE Transactions on Information Theory. 44 (4): 1369–1387. arXiv:quant-ph/9608006. doi:10.1109/18.681315. S2CID 1215697.

- Bacon, Dave (2006-01-30). "Operator quantum error-correcting subsystems for self-correcting quantum memories". Physical Review A. 73 (1): 012340. arXiv:quant-ph/0506023. Bibcode:2006PhRvA..73a2340B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.73.012340. S2CID 118968017.

- Knill, Emanuel (November 2, 2004). "Quantum Computing with Very Noisy Devices". Nature. 434 (7029): 39–44. arXiv:quant-ph/0410199. Bibcode:2005Natur.434...39K. doi:10.1038/nature03350. PMID 15744292. S2CID 4420858.

- Cory, D. G.; Price, M. D.; Maas, W.; Knill, E.; Laflamme, R.; Zurek, W. H.; Havel, T. F.; Somaroo, S. S. (1998). "Experimental Quantum Error Correction". Phys. Rev. Lett. 81 (10): 2152–2155. arXiv:quant-ph/9802018. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.81.2152. S2CID 11662810.

- Pittman, T. B.; Jacobs, B. C.; Franson, J. D. (2005). "Demonstration of quantum error correction using linear optics". Phys. Rev. A. 71 (5): 052332. arXiv:quant-ph/0502042. Bibcode:2005PhRvA..71e2332P. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.71.052332. S2CID 11679660.

- Chiaverini, J.; Leibfried, D.; Schaetz, T.; Barrett, M. D.; Blakestad, R. B.; Britton, J.; Itano, W. M.; Jost, J. D.; Knill, E.; Langer, C.; Ozeri, R.; Wineland, D. J. (2004). "Realization of quantum error correction". Nature. 432 (7017): 602–605. Bibcode:2004Natur.432..602C. doi:10.1038/nature03074. PMID 15577904. S2CID 167898.

- Schindler, P.; Barreiro, J. T.; Monz, T.; Nebendahl, V.; Nigg, D.; Chwalla, M.; Hennrich, M.; Blatt, R. (2011). "Experimental Repetitive Quantum Error Correction". Science. 332 (6033): 1059–1061. Bibcode:2011Sci...332.1059S. doi:10.1126/science.1203329. PMID 21617070. S2CID 32268350.

- Reed, M. D.; DiCarlo, L.; Nigg, S. E.; Sun, L.; Frunzio, L.; Girvin, S. M.; Schoelkopf, R. J. (2012). "Realization of Three-Qubit Quantum Error Correction with Superconducting Circuits". Nature. 482 (7385): 382–385. arXiv:1109.4948. Bibcode:2012Natur.482..382R. doi:10.1038/nature10786. PMID 22297844. S2CID 2610639.

- Ofek, Nissim; Petrenko, Andrei; Heeres, Reinier; Reinhold, Philip; Leghtas, Zaki; Vlastakis, Brian; Liu, Yehan; Frunzio, Luigi; Girvin, S. M.; Jiang, L.; Mirrahimi, Mazyar (August 2016). "Extending the lifetime of a quantum bit with error correction in superconducting circuits". Nature. 536 (7617): 441–445. Bibcode:2016Natur.536..441O. doi:10.1038/nature18949. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 27437573. S2CID 594116.

- Lassen, M.; Sabuncu, M.; Huck, A.; Niset, J.; Leuchs, G.; Cerf, N. J.; Andersen, U. L. (2010). "Quantum optical coherence can survive photon losses using a continuous-variable quantum erasure-correcting code". Nature Photonics. 4 (10): 700. arXiv:1006.3941. Bibcode:2010NaPho...4..700L. doi:10.1038/nphoton.2010.168. S2CID 55090423.

- Guo, Qihao; Zhao, Yuan-Yuan; Grassl, Markus; Nie, Xinfang; Xiang, Guo-Yong; Xin, Tao; Yin, Zhang-Qi; Zeng, Bei (2020-01-22). "Testing a Quantum Error-Correcting Code on Various Platforms". arXiv:2001.07998 [quant-ph].

Bibliography

- Daniel Lidar and Todd Brun, ed. (2013). Quantum Error Correction. Cambridge University Press.

- La Guardia, Giuliano Gadioli, ed. (2020). Quantum Error Correction: Symmetric, Asymmetric, Synchronizable, and Convolutional Codes. Springer Nature.

- Frank Gaitan (2008). Quantum Error Correction and Fault Tolerant Quantum Computing. Taylor & Francis.

- Freedman, Michael H.; Meyer, David A.; Luo, Feng: Z2-Systolic freedom and quantum codes. Mathematics of quantum computation, 287–320, Comput. Math. Ser., Chapman & Hall/CRC, Boca Raton, FL, 2002.

- Freedman, Michael H.; Meyer, David A. (1998). "Projective plane and planar quantum codes". Found. Comput. Math. 2001 (3): 325–332. arXiv:quant-ph/9810055. Bibcode:1998quant.ph.10055F.

- Lassen, Mikael; Sabuncu, Metin; Huck, Alexander; Niset, Julien; Leuchs, Gerd; Cerf, Nicolas J.; Andersen, Ulrik L. (2010). "Quantum optical coherence can survive photon losses using a continuous-variable quantum erasure-correcting code". Nature Photonics. 4 (1): 10. Bibcode:2010NaPho...4...10W. doi:10.1038/nphoton.2009.243.

External links

- Knill, E. (2004). "Quantum Computing with Very Noisy Devices". Nature. 434: 39–44. arXiv:quant-ph/0410199. Bibcode:2005Natur.434...39K. doi:10.1038/nature03350. PMID 15744292. S2CID 4420858.

- Error-check breakthrough in quantum computing

- "Topological Quantum Error Correction". Quantum Light. University of Sheffield. September 28, 2018 – via YouTube.