Quapaw

The Quapaw (or Arkansas and Ugahxpa) people are a tribe of Native Americans that coalesced in the Midwest and Ohio Valley. The Dhegiha Siouan-speaking tribe historically migrated from the Ohio Valley area to the west side of the Mississippi River and resettled in what is now the state of Arkansas; their name for themselves refers to this migration and traveling downriver.[3]

Flag of the Quapaw Nation | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 3,240[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| English, Quapaw language[2] | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity (Roman Catholicism), traditional tribal religion, Big Moon and Little Moon Native American Church | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Dhegihan peoples: Osage, Omaha, Ponca, Kansa |

The Quapaw are federally recognized as the Quapaw Nation.[4] The US federal government removed them to Indian Territory in 1834, and their tribal base has been in present-day Ottawa County in northeastern Oklahoma. The number of members enrolled in the tribe was 3,240 in 2011.[1]

Name

Algonquian-speaking people called the Quapaws /akansa/, and the French called them Arcansas.[5] The French named the Arkansas River and the territory and state of Arkansas for them.

Government

The Quapaw Nation is headquartered in Quapaw in Ottawa County, Oklahoma, in the northeast corner of the state. They have a 13,000-acre (53 km2) Quapaw tribal jurisdictional area.

The Quapaw people elect a tribal council and the tribal chairman, who serves a two-year term. The governing body of the tribe is outlined in the governing resolutions of the tribe, which were voted upon and approved in 1956 to create a written form of government (prior to 1956 the Quapaw Tribe operated on a hereditary chief system).[6] The Chairman is John L. Berrey.[1] Of the 3,240 enrolled tribal members, 892 live in the state of Oklahoma. Membership in the tribe is based on lineal descent.[7]

The tribe operates a Tribal Police Department and a Fire Department, which handles both fire and EMS calls. They issue their own tribal vehicle tags and have their own housing authority.[1]

Economic development

The tribe owns two smoke shops and motor fuel outlets, known as the Quapaw C-Store and Downstream Q-Store.[8]

Two casinos located in Quapaw, the Quapaw Casino and the Downstream Casino Resort, have generated most of the revenue for the tribe.[9][10] In 2012 the Quapaw Tribe's annual economic impact was measured at more than $225,000,000.[10] They also own and operate the Eagle Creek Golf Course and resort, located in Loma Linda, Missouri.[11] A third casino, Saracen Casino Resort, was completed in 2020 in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, and was the first purpose-built casino in Arkansas. Constructed at a cost of $350 million, it will employ over 1,100 full-time staff.[12]

The Tar Creek Superfund site has been listed by the Environmental Protection Agency for clean-up of environmental hazards. European-Americans leased lands for development that require remediation to remove toxic waste.

Language

The traditional Quapaw language is part of the Dhegiha branch of the Siouan language family. There are few remaining native speakers, but Quapaw was well documented in fieldnotes and publications from many individuals, including George Izard in 1827, Lewis F. Hadley in 1882, 19th-century linguist James Owen Dorsey, Frank T. Siebert in 1940, and by linguist Robert Rankin in the 1970s.[13]

Classes in the Quapaw language are taught at the tribal museum.[14] An online audio lexicon of the Quapaw language was created by editing old recordings of Elders speaking the language.[15]

Other efforts at language preservation and revitalization are being undertaken. In 2011 the Quapaw participated in the first annual Dhegiha Gathering. The Osage language program hosted and organized the gathering, held at the Quapaw tribe's Downstream Casino. Language-learning techniques and other issues were discussed and taught in workshops at the conference among the five cognate tribes.[16] The Annual Dhegiha Gathering was held in 2012 also at Downstream Casino.[17]

Cultural heritage

The Quapaw host cultural events throughout the year, primarily held at the tribal museum. These include Indian dice games, traditional singing, and classes in traditional arts, such as finger weaving, shawl making, and flute making. In addition, Quapaw language classes are held there.[18]

Fourth of July

The tribe's annual dance is during the weekend of the Fourth of July. This dance started shortly after the American Civil War,[19] 2011 was the 139th anniversary of this dance.[20] Common features of this powwow include gourd dance, war dance, stomp dance, and 49s. Other activities take place such as Indian football, handgame, traditional footraces, traditional dinners, turkey dance, and other dances such as Quapaw Dance, and dances from other area tribes.

This weekend is also when the tribe convenes the annual general council meeting, during which important decisions regarding the policies and resolutions of the Quapaw tribe are voted upon by tribal members over the age of eighteen.

History

The Quapaw Nation (known as Ugahxpa in their own language) are descended from a historical group of Dhegian-Siouan speaking people who lived in the lower Ohio River valley area. The modern descendants of this group also include the Omaha, Ponca, Osage and Kaw. The Quapaw and the other Dhegiha Siouan speaking tribes are believed to have migrated from the Ohio River valley after 1200 CE. Scholars are divided in whether they think the Quapaw and other related groups left before or after the Beaver Wars of the 17th century, in which the more powerful Five Nations of the Iroquois drove out other tribes from the Ohio Valley and retained the area for hunting grounds.[21][22]

They arrived at their historical territory, the area of the confluence of the Arkansas and Mississippi rivers, at minimum by the mid-17th century. The timing of the Quapaw migration into their ancestral territory in the historical period has been the subject of considerable debate by scholars of various fields. It is referred to as the "Quapaw Paradox" by academics. Many professional archaeologists have introduced numerous migration scenarios and time frames, but none has conclusive evidence.[23] Glottochronological studies suggest the Quapaw separated from the other Dhegihan-speaking peoples ranging between AD 950 to as late as AD 1513.[24]

The Illinois and other Algonquian-speaking peoples to the northeast referred to them as the Akansea or Akansa, meaning "land of the downriver people". As French explorers Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet met the Illinois before they did the Quapaw, they adopted this exonym for the more westerly people. English-speaking settlers who arrived later in the region adopted the name used by the French.

During years of colonial rule of New France, many of the French fur traders and voyageurs had an amicable relationship with the Quapaw, as with many other trading tribes.[25] Many Quapaw women and French men married and had families together. Pine Bluff, Arkansas, was founded by Joseph Bonne, a man of Quapaw-French ancestry.

Écore Fabre (Fabre's Bluff) was started as a trading post by the Frenchman Fabre and was one of the first European settlements in south central Arkansas. While the area was ruled by the Spanish from 1763–1789, following French defeat in the Seven Years' War, they did not have as many colonists in the area. After increased American settlement following the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, Écore Fabre was renamed as Camden.

English speakers tried to adapt French names to English phonetics: Chemin Couvert (French for "covered way or road") was gradually converted to "Smackover" by Anglo-Americans. They used this name for a local creek. Founded by the French, Le Petit Rocher was translated into English and renamed by Americans as Little Rock after the United States acquired the territory in the Purchase.

Numerous spelling variations have been recorded in accounts of tribal names, reflecting both loose spelling traditions, and the effects of transliteration of names into the variety of European languages used in the area. Some sources listed Ouachita as a Choctaw word, whereas others list it as a Quapaw word. Either way, the spelling reflects transliteration into French.

The following passages are taken from the public domain Catholic Encyclopedia, written early in the 20th century. It describes the Quapaw from the non-native perspective of that time. Some of the tribe has strong Cherokee kin relationships then and now.

A tribe now nearly extinct, but formerly one of the most important of the lower Mississippi region, occupying several villages about the mouth of the Arkansas, chiefly on the west (Arkansas) side, with one or two at various periods on the east (Mississippi) side of the Mississippi, and claiming the whole of the Arkansas River region up to the border of the territory held by the Osage in the north-western part of the state. They are of Siouan linguistic stock, speaking the same language, spoken also with dialectic variants, by the Osage and Kansa (Kaw) in the south and by the Omaha and Ponca in Nebraska. Their name properly is Ugakhpa, which signifies "down-stream people", as distinguished from Umahan or Omaha, "up-stream people". To the Illinois and other Algonquian tribes, they were known as 'Akansea', whence their French names of Akensas and Akansas. According to concurrent tradition of the cognate tribes, the Quapaw and their kinsmen originally lived far east, possibly beyond the Alleghenies, and, pushing gradually westward, descended the Ohio River – hence called by the Illinois the "river of the Akansea" – to its junction with the Mississippi, whence the Quapaw, then including the Osage and Kansa, descended to the mouth of the Arkansas, while the Omaha, with the Ponca, went up the Missouri.

Early European contact

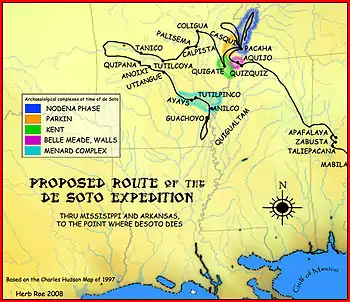

In 1541, when the Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto led an expedition that came across the town of Pacaha (also recorded by Garcilaso as Capaha), between the Mississippi River and a lake on the Arkansas side, apparently in present-day Phillips County. His party describe the village as strongly palisaded and nearly surrounded by a ditch. Archaeological remains and local conditions bear out the description. If the migration out of the Ohio Valley preceded the entrada, these people may have been the proto-Quapaw. However, given the use of the Tunica language in Pacaha and the evidence for a late Quapaw migration to Arkansas, it is likely that the people whom de Soto met were Tunica.[23]

The first certain encounters with Quapaw by Europeans occurred more than 130 years later. In 1673, the Jesuit Father Jacques Marquette accompanied the French commander Louis Jolliet in making his noted voyage down the Mississippi. He reportedly went to the villages of the Akansea, who gave him warm welcome and listened with attention to his sermons, while he stayed with them a few days. In 1682 La Salle passed by their villages, then five in number, of which one was on the east bank of the Mississippi. A Recollect father, Zenobius Membré, who accompanied the LaSalle expediton planted a cross and attempted to convert the Native Americans to Christianity.

The commander negotiated a peace with the tribe and formally "claimed" the territory for France. The Quapaw were uniformly kind and friendly toward the French. In spite of frequent shiftings, there were four Quapaw villages generally reported along the Mississippi River in this early period. They corresponded in name and population to four sub-tribes still existing, listed as Ugahpahti, Uzutiuhi, Tiwadimañ, and Tañwañzhita, or, under their French transliterations: Kappa, Ossoteoue, Touriman, and Tonginga. Kappa was reported to have been on the eastern bank of the Mississippi River and the other three located on the western bank in or near present-day Desha County, Arkansas. In 1721 depopulation led to the consolidation of Tourima and Tongigua into one village.[26] Ossoteoue or Osotouy was situated at the mouth of the Arkansas River and is now thought to be an archaeological site known as the Menard-Hodges Mounds.[27]

In 1686 the French commander Henri de Tonti built a post on the Arkansas River, near its mouth, that later was known as the Arkansas Post. This began European occupation of the Quapaw country. Tonti arranged also for a resident Jesuit missionary, but apparently without result. About 1697 a smallpox epidemic killed the greater part of the women and children of two villages. In 1727 the Jesuits, from their house in New Orleans, again took up the missionary work. In 1729 the Quapaw allied with the French against the Natchez, resulting in the practical extermination of the Natchez.

The French relocated the Arkansas Post upriver, trying to avoid flooding. After losing to the British in the Seven Years' War, France ceded its North American territories to Britain. This nation exchanged territory with Spain, which took over "control" of Arkansas and other former French territory west of the Mississippi River. It built new forts to protect its valued trading post with the Quapaw.

19th century

Shortly after the United States acquired the territory in 1803 by the Louisiana Purchase, it recorded the Quapaw as living in three villages on the south side of the Arkansas River about 12 miles (19 km) above Arkansas Post. In 1818, they made their first treaty with the US government, ceding all claims from the Red River to beyond the Arkansas and east of the Mississippi.

They kept a considerable tract between the Arkansas and the Saline, in the southeastern part of the state. Under continued US pressure, in 1824 they ceded this also, excepting 80 acres (320,000 m2) occupied by the chief Saracen below Pine Bluff. They expected to incorporate with the Caddo of Louisiana, but were refused permission. Successive floods in the Caddo country near the Red River pushed many toward starvation, and they wandered back to their old homes.

In 1834, under another treaty, the Quapaw were removed from the Mississippi valley areas to their present location in the northeast corner of Oklahoma, then Indian Territory.

Sarrasin (alternate spelling Saracen), their last chief before the removal, was a Roman Catholic and friend of the Lazarist missionaries (Congregation of the Missions), who had arrived in 1818. He died about 1830 and is buried adjoining St. Joseph's Church, Pine Bluff, where a memorial window preserves his name. The pioneer Lazarist missionary among the Quapaw was Rev. John M. Odin, who later served as the Archbishop of New Orleans.

In 1824 the Jesuits of Maryland, under Father Charles Van Quickenborne, took up work among the native and immigrant tribes of present-day Kansas and Oklahoma. In 1846 the Mission of St. Francis was established among the Osage, on Neosho River, by Fathers John Shoenmakers and John Bax, who extended their services to the Quapaw for some years. The Quapaw together with the associated remnant tribes, the Miami, Seneca, Wyandot and Ottawa, were served from the Mission of "Saint Mary of the Quapaws", at Quapaw, Oklahoma. Historians estimated their number at European encounter as 5000. The Catholic Encyclopedia noted the people had suffered from high fatalities due to epidemics, wars, removals, and social disruption. It documented their numbers as 3200 in 1687, 1600 in 1750, 476 in 1843, and 307 in 1910, including all mixed bloods.

Kinship, religion and culture

Besides the four established divisions already noted, the Quapaw have the clan system, with a number of gentes. Polygamy was practiced, but was not common. They were agricultural. Their towns were palisaded. Their town houses, or public structures, are referred to as longhouses and are constructed with timbers dovetailed together and bark roofs, were commonly erected upon large man-made mounds to guard against the frequent flooding. Their ordinary houses were rectangular and long enough to accommodate several families.

The Quapaw dug large ditches, and constructed fish weirs to manage their food supply. They excelled in pottery and in the painting of hide for bed covers and other purposes. The dead were buried in the ground, sometimes in mounds or in the clay floors of their houses, being frequently strapped to a stake in a sitting position and then covered with earth. They were friendly to the Europeans, while warring with the Chickasaw and other Southeastern tribes over resources and trade.

20th century

In the early 20th century, an account noted that the Dhegiha language, a branch of Siouan including the "dialects" of the Omaha, Ponca, Osage, Kansa, and Quapaw, has received more extended study. Rev. J.O. Dorsey published material about it under the auspices of the Bureau of American Ethnology, now part of the Smithsonian Institution.[28]

The USS Quapaw (ATF-110), a fleet ocean tug commissioned 6 May 1944, was named for the Quapaw people.

In media

The 2009 documentary Tar Creek, about the Tar Creek Superfund Site, located on Quapaw tribal lands, which at one time was considered to be the worst environmental disaster in the country. The film discusses the alleged racism of environmental and governmental practices that led to the neglect and lack of regulation resulting in this site, and subsequent ill effects, including lead poisoning of a high percentage of children.

In 2018, Infinite Productions produced a documentary titled The Pride of the Ogahpah about the story of the Downstream Casino Resort, which is operated by The Quapaw Nation.

Notable Quapaw people

- Louis Ballard, (1931–2007) composer, artist, and educator

- Victor Griffin (c. 1873–1958), chief, interpreter, and peyote roadman

- Barbara Kyser-Collier, tribal governmental figure

- Ardina Moore, language teacher, regalia maker/textile artist

- Saracen, chief and recipient of a presidential medal[29]

- Tall Chief (c. 1840–1918), chief, peyote roadman

See also

Notes

- 2011 Oklahoma Indian Nations Pocket Pictorial Directory Archived 12 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Oklahoma Indian Affairs Commission, 2011: 30. Retrieved 28 Jan 2012.

- "Quapaw." Archived 10 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine Ethnologue. Retrieved 28 Jan 2012.

- "Quapaw Tribe, OK – Official Website – Tribal Name". www.quapawtribe.com. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- "Welcome to the Quapaw Nation."

- Bright, William (2007). Native American Placenames of the United States. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-806135984.

- "Quapaw Tribe Governing Resolutions."

- "Quapaw Enrollment"

- "Quapaw Businesses.", Quapaw tribal website, 2013 (retrieved 8 February 2013)

- "Directions." Archived 27 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine Downstream Casino Resort. 2008 (retrieved 12 August 2010)

- "Casino Pumps 1 Billion: Downstream Casino Economic Impact", Neosho Daily News, 19 January 2013 (retrieved 8 February 2013)

- "Golf" Archived 28 January 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Downstream Casino Resort website, 2013 (retrieved 8 February 2013)

- "Quapaw Nation Cuts Ribbon on Casino Resort". KARK.com. 20 October 2020.

- Quapaw Historical Written Works, Quapaw Tribal Ancestry

- "Quapaw language", Quapaw Tribal website, 2011 (retrieved 10 September 2011)

- Quapaw Language

- "Dhegiha Gathering" Archived 19 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Dhegiha Gathering Article. 2011, Osage Tribe website (retrieved 10 September 2011)

- "2nd Dhegiha Gathering." 2nd Dhegiha Gathering Notice. 2013, Quapaw Tribe website (retrieved 8 February 2013)

- "Calendar", Quapaw Tribe Website, 2008 (retrieved 12 August 2010)

- Baird, David (1975). The Quapaw People. Indian Tribal Series.

- "Powwows.", Tribal website. 2011 (retrieved 10 September 2011)

- Rollins, Willard (1995). The Osage: An Enthnohistorical Study of Hegemony on the Prairie-Plains. Columbia: University of Missouri Press. pp. 96–100.

- Louis F. Burns, "Osage" Archived 2 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, retrieved 2 March 2009

- Ethridge, Robbie (2008). The Transformation of the Southeastern Indians, 1540–1760. University Press of Mississippi.

- "Dhegihan and Chiwere Siouans in the Plains: Historical and Archaeological Perspectives". Plains Anthropologist: 394. 2004.

- Havard, Gilles (2003). Histoire de l'Amérique française. Paris: Flamarion.

- "Quapaw". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- Ford, James A. (1961), Menard Site: the Quapaw Village of Osotouy On the Arkansas River, New York: American Museum of Natural History

- Pilling, Siouan Bibliography

- Matheson, Luke (13 August 2019). "Who Was Chief Saracen of the Quapaw Tribe?". Pine Bluff Commercial.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Quapaw. |

| Wikisource has the text of an 1879 American Cyclopædia article about Quapaw. |

- Quapaw Tribe, official website

- Quapaw Tribal Ancestry, official tribal sanctioned site with genealogy information, pictures, and stories

- Quapaw Language, official tribal sanctioned site with language information, words, audio clips, and source information

- Quapaw, Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture

- The Quapaw Tribe of Oklahoma and The Tar Creek Project, EPA

- Quapaw Indian Tribe History, Access Genealogy

- Tar Creek, Tar Creek documentary website