Chickasaw Nation

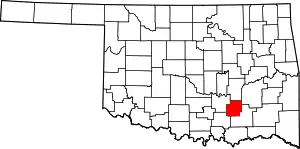

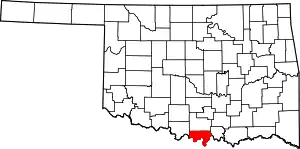

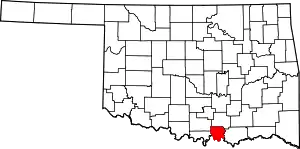

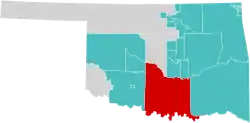

The Chickasaw Nation (Chickasaw: Chikashsha I̠yaakni') is a federally recognized Native American nation, with its headquarters located in Ada, Oklahoma in the United States. They are the indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands. Currently, the nation's jurisdictional territory[4] includes about 7,648 square miles of south-central Oklahoma, including the Bryan, Carter, Coal, Garvin, Grady, Jefferson, Johnston, Love, McClain, Marshall, Murray, Pontotoc, and Stephens counties. These counties are separated into four districts – the Pontotoc, Pickens, Tishomingo, and Panola – to ensure a relatively equal population within each county.[5] It is estimated that their population today stands around 38,000, with the majority of Chickasaw population currently residing in the state of Oklahoma.[6] In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, European Americans knew the Chickasaw as one of the historic Five Civilized Tribes (Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminole nations - all of which were based in the Southeastern United States),[7] due to later adoption of a number of practices of the European settlers, including the adoption of centralized governments with written constitutions, intermarriages with the white settlers, literacy, Christianity, market participation, and slaveholding. Today, the Chickasaw Nation is the thirteenth largest federally recognized tribe in the United States.

The Chickasaw Nation

| |

|---|---|

Flag  Seal | |

Location (red) in the U.S. state of Oklahoma | |

| Constitution | August 30, 1856 |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Bill Anoatubby |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7,648 sq mi (19,810 km2) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 38,000[3] |

| Demonym(s) | Chickasaw |

| Time zone | UTC−06:00 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−05:00 (CDT) |

| Area code(s) | 918 and 539 |

| Website | chickasaw |

The Chickasaw language, Chikashshanompa’, is classified as part of the Muskogean language family, and is the main language of the Chickasaw Nation. This is primarily an oral language, with no written component.[8] A significant part of their culture is passed on to each generation through their oral tradition, consisting of traditional stories that speak to the tribe’s legacy and even a brother-like relationship with the Choctaw. The similarities in the language of the Chickasaw and the Choctaw have prompted anthropologists to propose a number of theories regarding the origins of the Chickasaw Nation as it continues to remain uncertain.[9] Clans within the Chickasaw Nation are separated into two moieties: the Impsaktea and the Intcutwalipa, with each clan having their own leaders. Their tradition of matrilineal descent provides the basic societal structure of the nation, with children becoming members and under the care of their mother’s clan.[10]

History

Origins

The Mississippian Cultures developed between ~850-950CE around the Mississippi River with some regional variations. This was a period of increasing sociopolitical complexity, with the intensification of agriculture, settlements in larger towns or chiefdoms, as well as the formation of strategic alliances to facilitate communication. There is evidence of the organization of labor from the mounds built that remain today, as well as the skills of artisans and craftmanship from the elaborate and intricate remains of burials.[11] Furthermore, as chiefdoms arose within the Chickasaw Nation in addition to across the Southeast, the increased social complexity and population growth were sustained by effective and widespread farming practices. While the origins of the Chickasaw continue to remain uncertain, there have been a number of proposed theories by anthropologists and historians. One theory is that the Chickasaw were at one time a part of the Choctaw and later branched off, given their close connections linguistically and geographically.[12] Another is that they were descendants of the pre-historic Mississippian tribes, having migrated from the West given their oral histories.[13] According to some of their oral stories, the Chickasaw first settled in the Chickasaw Old Fields, what is currently northern Alabama today, and later re-established themselves near the Tombigbee River.[14]

European Contact 16th-17th century

Hernando de Soto is credited as being the first European to contact the Chickasaw during his travels of 1540, and along with his army, were some of the first, and last, European explorers to come into contact with the Mississippian cultures and nations of the Southeast. He discovered them to be an agrarian nation with the political organization of a chiefdom governmental system, with the head chief residing in the largest and main temple mound in the chiefdom, with the remaining family lineage and commoners spreading out across the villages.[15] After an uneasy truce regarding letting the Spanish stay in their camps for the winter and surviving on the tribe's food supply, the Chickasaws planned a surprise night attack on Desoto and his men as they were in preparation to leave months later. Thus they successfully sent a defiant message to their European enemies not to return to their land. As a result, 150 years passed before the Chickasaw received another European expedition.[16]

The next encounter the Chickasaw Nation had with European settlers was with French colonists, Robert La Salle and Henri Tonti.[17] Not long after, by the end of the 17th century, the Chickasaw Nation had established successful trade relationships with the British in the Carolinas as well as the French. In exchange for hides and slaves, the Chickasaw obtained metal tools, guns, and other supplies from the Europeans.[18] The Chickasaw had a smaller population, of around 3,500-4,000 people, in comparison to their surrounding neighbors such as the Choctaw, with a population of about 20,000.[19] However, there became increased efforts by the English and the French to establish and maintain strong alliances with the Chickasaw Nation as the struggles for power in the area relied primarily upon the allying of not only the Chickasaw, but the surrounding sovereign tribes in the region as well. Their effective trade routes later became the focal point of the wars fought between Great Britain and France.[20] During the colonial period, some Chickasaw towns traded with French colonists from La Louisiane, including their settlements at Biloxi, or Mobile.

18th-19th century

After the American Revolutionary War, the new state of Georgia was trying to strengthen its claim to western lands, which it said went to the Mississippi River under its colonial charter. It also wanted to satisfy a great demand by planters for land to develop, and the state government, including the governor, made deals to favor political insiders. Various development companies formed to speculate in land sales. After a scandal in the late 1780s, another developed in the 1790s. In what was referred to as the Yazoo land scandal of January 1795, the state of Georgia sold 22 million acres of its western lands to four land companies, although this territory was occupied by the Chickasaw and other tribes, and there were other European nations with some sovereignty in the area.[21] This was the second Yazoo land sale, which generated outrage when the details were publicized. Reformers passed a state law forcing the annulment of this sale in February 1796.[22] But the Georgia-Mississippi Company had already sold part of its holdings to the New England Mississippi Company, and it had sold portions to settlers. Conflicts arose as settlers tried to claim and develop these lands. Georgia finally ceded its claim to the US in 1810, but the issues took nearly another decade to resolve.

Abraham Bishop of New Haven, Connecticut, wrote a 1797 pamphlet to address the land speculation initiated by the Georgia-Mississippi Company. Within this discussion, he wrote about the Chickasaw and their territory in what became Mississippi:

The Chickasaws are a nation of Indians who inhabit the country on the east side of the Mississippi, on the head branches of the Tombeckbe (sic), Mobille (sic) and Yazoo rivers. Their country is an extensive plain, tolerably well watered from springs, and a pretty good soil. They have seven towns, and their number of fighting men is estimated at 575.[23]

The Chickasaw sold a section of their lands with the Treaty of Tuscaloosa, resulting in the loss of what became known as the Jackson Purchase, in 1818. This area included western Kentucky and western Tennessee, both areas not heavily populated by members of the tribe. They remained in their primary homeland of northern Mississippi and northwest Alabama until the 1830s. After decades of increasing pressure by federal and state governments to cede their land, as European Americans were eager to move into their territory and had already begun to do so as squatters or under fraudulent land sales, the Chickasaw finally agreed to cede their remaining Mississippi Homeland to the U.S. under the Treaty of Pontotoc Creek and relocate west of the Mississippi River to Indian Territory.

The Chickasaw removal is one of the most traumatic episodes in the history of the nation. As a result of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Chickasaw Nation was forced to move to Indian territory, suffering a significant decline in population. However, due to the negotiating skills of the Chickasaw leaders, they were led to favorable sales of their land in Mississippi. Of the Five Civilized Tribes, the Chickasaw were one of the last ones to move. In 1837, the Chickasaw and Choctaw signed the Treaty of Doaksville,[24] by which the Chickasaw purchased the western lands of the Choctaw Nation in Indian Territory. Their area in the western area of the nation was called the Chickasaw District. It consisted of what are now Panola, Wichita, Caddo, and Perry counties.

Although originally the western boundary of the Choctaw Nation extended to the 100th meridian, virtually no Chickasaw lived west of the Cross Timbers, due to continual raiding by the Plains Indians of the southern region. The United States eventually leased the area between the 100th and 98th meridians for the use of the Plains tribes. The area was referred to as the "Leased District".[25]

The division of the Choctaw Nation was ratified by the Choctaw–Chickasaw Treaty of 1854. The Chickasaw constitution, establishing the nation as separate from the Choctaw, was signed August 30, 1856, in their new capital of Tishomingo (now Tishomingo, Oklahoma). The first Chickasaw governor was Cyrus Harris. The nation consisted of four divisions; Tishomingo County, Pontotoc County, Pickens County, and Panola County. Law enforcement in the nation was provided by the Chickasaw Lighthorsemen. Non-Indians fell under the jurisdiction of the Federal court at Fort Smith.

Following the Civil War, the United States forced the Chickasaw Nation into a new peace treaty due to their support for the Confederacy. Under the new treaty, the Chickasaw (and Choctaw) ceded the "Leased District" to the United States.

20th century to present

In 1907, when Oklahoma entered the union as the 46th state, the role of tribal governments in Indian Territories ceased, and as a result, the Chickasaw people were then granted United States citizenship. For decades, the United States appointed representatives for the Chickasaw Nation until 1971. Douglas H. Johnston was the first man to serve in this capacity. Governor Johnston served the Chickasaw Nation from 1906 until his death in 1939 at age 83. Though it may have seemed like the federal government finally achieved their goal of completely assimilating the Chickasaw Nation into mainstream American life, the Chickasaw people continued to practice traditional activities and gather together socially, believing that the community involvement would sustain their culture, language, and core beliefs and values. This gave rise to the movement towards which the Chickasaw would govern themselves.

During the 1960s and the period of the civil rights movement, Native American Indian activism was also on the rise. A group of Chickasaw met at Seeley Chapel, a small country church near Connerville, Oklahoma, to work toward the re-establishment of its government. With the passage of Public Law 91-495, their tribal government was recognized by the United States. In 1971, the people held their first tribal election since 1904. They elected Overton James by a landslide as governor of the Chickasaw Nation. Thus, the Chickasaw communities became even closer in support of one another for the greater good of the Chickasaw peoples.

Since the 1980s, the tribal government has focused on building an economically diverse base to generate funds that will support programs and services to Indian people.

Culture

Language

Chikashshanompa’, a traditionally oral language, is the primary and official language of the Chickasaw Nation. Over 3,000 years old,[26] Chikashshanompa’ is part of the Muskogean language family and is very similar to the Choctaw language. There has been a great decline over the years in the number of speakers, as the language is spoken by less than two hundred people today, with the majority being Chickasaw elders.[27] The Chickasaw language was often discouraged in students attending school and was often discouraged in even tribally run schools.[28] Recently, the Chickasaw Nation of Oklahoma has promoted the Chickasaw Language Revitalization Program enacted in 2007. The program focuses on the Master Apprentice Program, which pairs a language-learning student with an individual already fluent in Chikashshanompa’ in attempts to gain conversational fluency.[29] Other attempts at language revitalization have included establishing university language courses, creating a language learning app, youth language clubs, and more.

Religion and cultural practice

At the core of Chickasaw religious beliefs and traditions is the supreme deity Aba' Binni'li' (Sitting or Dwelling Above), the spirit of fire and giver of life, light, and warmth. Aba' Binni'li' is believed to live above the clouds along with a number of other lesser deities such as the spirits of the sky, clouds, evil spirits, and more.[30] The Chickasaws also believe in a life after death, believing that those who lead a good life will follow the path to heaven while those following an evil path suffer in the land of the witches. Corpses were to be buried under their homes, facing west with faces painted red, and be surrounded by their individual possessions.

The Chickasaw Nation follows the traditional monogamous marriage system,[31] with the groom obtaining the blessings of the wife’s parents and following with a simple ceremony soon after. Marriage ceremonies were all arranged by women. Adultery is a misdemeanor seriously looked down upon with severe private as well as public consequences since this was thought to bring shame and dishonor to the families.[32] As the Chickasaws practice matrilineal descent, children usually follow their mother’s house/clan name.

The Green Corn Festival is one of the largest and most important ceremonies of the Chickasaw Nation. The festival is an important religious ceremony that takes place in the latter of summer, lasting two to eight days serving as a religious renewal in addition to thanksgiving, as all members of the tribe give thanks for the year’s corn harvest and pray to Aba' Binni'li'.[33] Major events held during the celebration includes a two-day fast, a purification ceremony, the forgiveness of minor sins, the Stomp Dance (the most well-known traditional dances of the Chickasaw), major ball games, and more.[34]

Government and politics

The Chickasaw Nation is headquartered in Ada, Oklahoma. Their tribal jurisdictional area is in Bryan, Carter, Coal, Garvin, Grady, Jefferson, Johnston, Love, McClain, Marshall, Murray, Pontotoc, and Stephens counties in Oklahoma. The tribal governor is Bill Anoatubby.[2] Bill Anoatubby was elected governor in 1987, and at the time, the tribe had a larger spending budget than funds available.[35] Anoatubby's effective management gradually led the tribe toward progress, as tribal operations and funding have increased exponentially. Governor Anoatubby also lists some of his primary goals as meeting the needs and desires of the Chickasaw people by providing opportunities for employment, higher education, as well as health care services.

The Chickasaw Nation’s current three-department system of government was established with the ratification of the 1983 Chickasaw Nation Constitution. The tribal government takes the form of a democratic republic. The governor and the lieutenant governor are elected to serve four-year terms and run for political office together. The Chickasaw government also has an executive branch, legislative branch, and judicial department. In addition to electing a governor along with a lieutenant governor, voters also select thirteen members to make up the tribal legislature (with three-year terms), and three justices to make up the tribal supreme court.[36] The elected officials provided for in the Constitution believe in a unified commitment, whereby government policy serves the common good of all Chickasaw citizens. This common good extends to future generations as well as today’s citizens.

The structure of the current government encourages and supports infrastructure for strong business ventures and an advanced tribal economy. The use of new technologies and dynamic business strategies in a global market are also encouraged. Monies generated in business are divided between investments for further diversification of enterprises and support of tribal government operations, programs, and services for Indian people.[37] This unique system is key to the Chickasaw Nation’s efforts to pursue self-sufficiency and self-determination, ensuring the continuous enrichment and support of Indian lives.

Revenues generated by Chickasaw Nation tribal business endeavors fund more than 200 programs and services. These programs cover education, health care, youth, aging, housing and more, all of which directly benefit Chickasaw families, Oklahomans and their communities.[38]

Governor Bill Anoatubby appointed Charles W. Blackwell as the Chickasaw Nation's first Ambassador to the United States in 1995.[39] (Blackwell had previously served as the Chickasaw delegate to the United States from 1990 to 1995). At the time of his appointment in 1995, Blackwell became the first Native American tribal ambassador to the United States government. Blackwell served in Washington as ambassador from 1995 until his death on January 3, 2013.[39] Governor Bill Anoatubby named Neal McCaleb ambassador-at-large in 2013, a role similar to that of the late Charles Blackwell.

Economy

The Chickasaw Nation operates more than 100 diversified businesses in a variety of services and industries, including manufacturing, energy, health care, media, technology, hospitality, retail and tourism.[40] Among these are Bedré Fine Chocolate in Davis, Lazer Zone Family Fun Center and the McSwain Theatre in Ada; The Artesian Hotel in Sulphur; Chickasaw Nation Industries in Norman, Oklahoma; Global Gaming Solutions, LLC; KADA (AM), KADA-FM, KCNP, KTLS, KXFC, and KYKC radio stations in Ada; and Treasure Valley Inn and Suites in Davis. In 1987, with funding from the US federal government, the Chickasaw Nation operated just over thirty programs in hopes of eventually reaching the state of being in a firm financial base. Today, the nation has more than two hundred tribally funded programs as well as more than sixty federally funded programs providing services from housing, education, entertainment, employment, healthcare, and more.

Governor Anoatubby highly prioritizes the services available to the Chickasaw people. Two health clinics (in Tishomingo and Ardmore), as well as the Chickasaw Nation Medical Center, was established in Ada, Oklahoma in 1987. Not long after, many more health clinics and facilities have opened as well, with even a convenient housing facility on the campus of the Chickasaw Nation Medical Center designed to relieve families and patients of travel and lodging costs if traveling far from home. Increases in higher education funding and scholarships have enabled many students to pursue higher education, with funding increasing from $200,000 thirty years ago to students receiving more than $15.6 million in scholarships, grants, and other educational support.[41] The Chickasaw Nation is also contributing heavily to the tourism industry in Oklahoma. In 2010, the Chickasaw Cultural Center opened, attracting more than 200,000 visitors from around the world as well as providing hundreds of employment opportunities to local residents.[42] In this year alone, the Chickasaw Nation also opened a Welcome Center, Artesian Hotel, Chickasaw Travel Shop, Chickasaw Conference Center and Retreat, Bedré Fine Chocolate Factory, and the Salt Creek Casino. In 2002, the Chickasaw Nation purchased Bank2 with headquarters in Oklahoma City. It was renamed Chickasaw Community Bank in January of 2020. It started with $7.5 million in assets and has grown to $135 million in assets today.[43] The Chickasaw Nation also operates many historical sites and museums, including the Chickasaw Nation Capitols, and Kullihoma Grounds, as well as a number of casinos. Their casinos include Ada Gaming Center, Artesian Casino, Black Gold Casino, Border Casino, Chisholm Trail Casino, Gold Mountain Casino, Goldsby Gaming Center, Jet Stream Casino, Madill Gaming Center, Newcastle Casino, Newcastle Travel Gaming, RiverStar Casino, Riverwind Casino, Treasure Valley Casino, Texoma Casino, SaltCreek Casino, Washita Casino and WinStar World Casino. They also own Lone Star Park in Grand Prairie, Texas and Remington Park Casino in Oklahoma City. The estimated annual tribal economic impact in the region from all sources is more than $3.18 billion.[2]

Notable people

- Bill Anoatubby, Governor of the Chickasaw Nation since 1987

- Jodi Byrd, Literary and political theorist

- Jack Brisco and Gerry Brisco, pro-wrestling tag team

- Stephanie Byers, the first Native American openly transgender person elected to office in America[44]

- Jeff Carpenter, recording artist and co-founder of the Native American music group Injunuity

- Edwin Carewe (1883–1940), movie actor and director[45]

- Charles David Carter, Democratic U. S. Congressman from Oklahoma[46]

- Travis Childers, U.S. Congressman from Mississippi

- Helen Cole (1922-2004), politician from Oklahoma, served in both the state house of Representatives and the state Senate, in addition to mayor of Moore, Oklahoma. One of her sons, Tom Cole, is a member of the U.S. House of Representatives.

- Tom Cole, Republican US Congressman from Oklahoma

- Hiawatha Estes, architect

- Cyrus Harris, first Governor of the Chickasaw nation

- John Herrington, astronaut, first enrolled Native American to travel in space

- Linda Hogan, author, writer-in-residence of the Chickasaw Nation

- Overton James, Governor of the Chickasaw Nation (1963-1987)

- Douglas H. Johnston, Governor of Chickasaw Nation (1898-1902 and 1904-1939)

- Neal McCaleb, civil engineer and politician

- Bryce Petty, quarterback for the Miami Dolphins

- Eula Pearl Carter Scott, pilot, later elected to the Chickasaw legislature, where she served three terms[47][48]

- Jerod Impichchaachaaha' Tate, composer and pianist

- Rebecca Sandefur, sociologist and winner of a MacArthur "Genius" Fellowship

- Te Ata Fisher storyteller and actress[49]

- Fred Waite (1853 - 1895), politician representative, senator, Speaker of the House and Attorney General of Chickasaw Nation

- Estelle Chisholm Ward, first woman to represent tribal interests in Washington, D.C.

- Kevin K. Washburn, attorney, federal government official and law professor

Notes

- "U.S. Census website". Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- 2011 Oklahoma Indian Nations Pocket Pictorial Directory. Archived April 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Oklahoma Indian Affairs Commission. 2011: 8. Retrieved January 2, 2012.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20050211064810/http://www.census.gov/statab/www/sa04aian.pdf

- "Geographic Information | Chickasaw Nation". chickasaw.net. Retrieved September 13, 2020.

- “Districts.” Legislative, legislative.chickasaw.net/Districts.aspx.

- “Chickasaw.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., www.britannica.com/topic/Chickasaw-people.

- "Five Civilized Tribes | The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture". www.okhistory.org. Retrieved October 15, 2020.

- “Language.” Chickasaw Nation, chickasaw.net/Our-Nation/Culture/Language.aspx.

- Atkinson, James R. Splendid Land, Splendid People: the Chickasaw Indians to Removal. Univ. of Alabama Press, 2004.

- Bander, Margaret. “Glimpses of Local Masculinities: Learning from Interviews with Kiowa, Comanche, Apache and Chickasaw Men.” Journal of the Southern Anthropological Society, vol. 31, 2005, www.southernanthro.org/downloads/publications/SA-archives/2005-vol31.pdf#page=2.

- Cobb, Charles R. “Mississippian Chiefdoms: How Complex?” Annual Review of Anthropology, vol. 32, no. 1, 2003, pp. 63–84., doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.32.061002.093244.

- Gibson, Arrell M. “Chickasaw Ethnography: An Ethnohistorical Reconstruction.” Ethnohistory, vol. 18, no. 2, 1971, p. 99., doi:10.2307/481307.

- Perdue, Theda, and Michael D. Green. The Columbia Guide to American Indians of the Southeast. Columbia University Press, 2012. https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Columbia_Guide_to_American_Indians_o.html?id=-RBJCyp2bFIC

- Gorman, Joshua M. Building a Nation: Chickasaw Museums and the Construction of Chickasaw History and Heritage. 2009. https://books.google.com/books/about/Building_a_Nation.html?id=9DyQkQEACAAJ

- Hally, David J., and John F. Chamblee. “The Temporal Distribution and Duration of Mississippian Polities in Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and Tennessee.” American Antiquity, vol. 84, no. 3, 2019, pp. 420–437., doi:10.1017/aaq.2019.31.

- Green, Richard 2007 Chickasaw lives. Volume one, Explorations in tribal history. Ada, Okla.: Chickasaw Press.

- “Chickasaw History.” Chickasaw, www.tolatsga.org/chick.html.

- Johnson, Jay K. “Stone Tools, Politics, and the Eighteenth-Century Chickasaw in Northeast Mississippi.” American Antiquity, vol. 62, no. 2, 1997, pp. 215–230., doi:10.2307/282507.

- Atkinson, James R. Splendid Land, Splendid People: the Chickasaw Indians to Removal. Univ. of Alabama Press, 2004.

- Champagne, Duane. Social Order and Political Change: Constitutional Governments among the Cherokee, the Choctaw, the Chickasaw, and the Creek. Stanford University Press, 1998.

- Lamplugh, George R. (2010). "James Gunn: Georgia Federalist, 1789-1801". Georgia Historical Quarterly. 94 (3): 313.

- George R. Lamplugh (1986). Politics on the Periphery: Factions and Parties in Georgia, 1783-1806. University of Delaware Press. pp. 148–. ISBN 978-0-87413-288-5.

- Bishop, Abraham (1797), Georgia Speculation Unveiled; In Two Numbers, New Haven: Elisha Babcock, p. 42

- “Doaksville.” Doaksville and Fort Towson | Oklahoma Historical Society, www.okhistory.org/sites/ftdoaksville.

- Arrell Morgan Gibson (1981). "The Federal Government in Oklahoma". Oklahoma: A History of Five Centuries. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 112. ISBN 0-8061-1758-3.

- Russon, Author: Mary-Ann. “Chickasaw Nation: The Fight to Save a Dying Native American Language.” Chickasaw Nation: The Fight to Save a Dying Native American Language | Indigenous Governance Database, 1 Jan. 1970, nnigovernance.arizona.edu/chickasaw-nation-fight-save-dying-native-american-language.

- Munro, Pamela, and Catherine Willmond. Let's Speak Chickasaw = Chikashshanompa' Kilanompoli'. University of Oklahoma Press, 2008.

- Cobb, Amanda J. Listening to Our Grandmothers' Stories: the Bloomfield Academy for Chickasaw Females, 1852-1949. University of Nebraska Press, 2007.

- “Chickasaw Nation.” Indian Country - Chickasaw Language Revitalization, msu-anthropology.github.io/indian-country/sites/chickasaw-language-revitalization.html.

- Gibson, Arrell M. “Chickasaw Ethnography: An Ethnohistorical Reconstruction.” Ethnohistory, vol. 18, no. 2, 1971, p. 99., doi:10.2307/481307.

- “Marriage.” Chickasaw Nation, chickasaw.net/Our-Nation/Culture/Society/Marriage.aspx.

- Gibson, Arrell M. “Chickasaw Ethnography: An Ethnohistorical Reconstruction.” Ethnohistory, vol. 18, no. 2, 1971, p. 99., doi:10.2307/481307.

- Admin. “The Green Corn Ceremony.” Native American Netroots, 5 May 2011, nativeamericannetroots.net/diary/951.

- “Stomp Dance.” Chickasaw Nation, www.chickasaw.net/Our-Nation/Culture/Society/Social-Dances.aspx.

- “Biography.” Governor, governor.chickasaw.net/About/Biography.aspx.

- Fitzgerald, David, et al. Chickasaw: Unconquered and Unconquerable. Chickasaw Press, 2006. https://books.google.com/books/about/Chickasaw.html?id=G3mhTOLHX5AC

- Farley, Tim. “Leading to Success: Governor Anoatubby Shows the Chickasaw Nation New Heights.” IonOKlahoma Online, www.ionok.com/oklahoma-magazine/cover/leading-success-governor-anoatubby-shows-chickasaw-nation-new-heights/.

- “Businesses.” Chickasaw Nation, chickasaw.net/Our-Nation/Economic-Development/Businesses.aspx.

- "Chickasaw Nation Ambassador Charles W. Blackwell – a Man of Vision". KXII. January 4, 2013. Archived from the original on January 8, 2013. Retrieved January 20, 2013.

- “Businesses.” Chickasaw Nation, chickasaw.net/Our-Nation/Economic-Development/Businesses.aspx.

- Farley, Tim. “Leading to Success: Governor Anoatubby Shows the Chickasaw Nation New Heights.” IonOKlahoma Online, www.ionok.com/oklahoma-magazine/cover/leading-success-governor-anoatubby-shows-chickasaw-nation-new-heights/.

- "Press Release | Chickasaw Nation". chickasaw.net. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- "Transgender and non-binary candidates elected in several US 'firsts'". Largs and Millport Weekly News.

- "Native American Data for Jay J Fox". RootsWeb. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- "Carter, Charles David (1868–1929)." Archived November 2, 2012, at the Wayback Machine Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Retrieved 6 May 2012.

- "Chickasaw Nation Hall of Fame - Eula Pearl Carter Scott". Hof.chickasaw.net. Archived from the original on August 8, 2016. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- oklahoma state senate staff. "Oklahoma State Senate - News". Oksenate.gov. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- "TE ATA (1895-1995)". Archived from the original on November 24, 2013. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

References

- Atkinson, James R. Splendid Land, Splendid People: the Chickasaw Indians to Removal. Univ. of Alabama Press, 2004.

- Ethridge, Robbie Franklyn. From Chicaza to Chickasaw: the European Invasion and the Transformation of the Mississippian World, 1540-1715. Univ. of North Carolina Press, 2013.

- Davis, Jenny L. “Language Affiliation and Ethnolinguistic Identity in Chickasaw Language Revitalization.” Language & Communication, vol. 47, 2016, pp. 100–111., doi:10.1016/j.langcom.2015.04.005.

- Gibson, Arrell M. “Chickasaw Ethnography: An Ethnohistorical Reconstruction.” Ethnohistory, vol. 18, no. 2, 1971, p. 99., doi:10.2307/481307.

- Green, Richard. Chickasaw Lives. Chickasaw Press, 2007.

- Perdue, Theda, and Michael D. Green. The Columbia Guide to American Indians of the Southeast. Columbia University Press, 2012.

- “Native American Spaces: Cartographic Resources at the Library of Congress: Indian Territory.” Research Guides, guides.loc.gov/native-american-spaces/cartographic-resources/indian-territory.

- Pritzker, Barry M. A Native American Encyclopedia: History, Culture, and Peoples. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0-19-513877-1.

- Jean, Wendy St. “Trading Paths: Mapping Chickasaw History in the Eighteenth Century.” The American Indian Quarterly, vol. 27, no. 3, 2003, pp. 758–780., doi:10.1353/aiq.2004.0085.

- Fitzgerald, David, et al. Chickasaw: Unconquered and Unconquerable. Chickasaw Press, 2006.

- Swanton, John Reed. Chickasaw Society and Religion. University of Nebraska Press, 2006.

- “Chickasaw Nation.” SPTHB, 24 June 2017, www.spthb.org/about-us/who-we-serve/chickasaw-nation/.

- “GOVERNOR ANOATUBBY SAYS STATE OF THE CHICKASAW NATION IS THE STRONGEST IT'S EVER BEEN.” Chickasaw Nation, 2019, chickasaw.net/News/Press-Releases/Release/Gov-Anoatubby-says-state-of-Chickasaw-Nation-is-t-52146.aspx.

- “Chickasaw: The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.” Chickasaw | The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture, www.okhistory.org/publications/enc/entry.php?entryname=CHICKASAW.

- Ellis, Randy. “Business Is Booming for Chickasaw Nation.” Oklahoman.com, Oklahoman, 7 Dec. 2017, oklahoman.com/article/5575008/business-is-booming-for-chickasaw-nation.

- “Mission, Vision & Core Values.” Chickasaw Nation, chickasaw.net/Our-Nation/Government/Mission-Vision-Core-Values.aspx.

Further reading

- A. G. Young and S. M. Miranda, "Cultural Identity Restoration and Purposive Website Design: A Hermeneutic Study of the Chickasaw and Klamath Tribes," 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Waikoloa, HI, 2014, pp. 3358-3367, doi: 10.1109/HICSS.2014.417.

- Galloway, Patricia Kay. Choctaw Genesis, 1500-1700. University of Nebraska Press, 1998.

- Johnson, Jay K. “Stone Tools, Politics, and the Eighteenth-Century Chickasaw in Northeast Mississippi.” American Antiquity, vol. 62, no. 2, 1997, pp. 215–230., doi:10.2307/282507.

- Johnson, Neil R.; C. Neil Kingsley (editor). The Chickasaw Rancher. Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2001 (Revision of 1960 edition). ISBN 978-0-87081-635-2

- Kappler, Charles (ed.). "TREATY WITH THE CHOCTAW AND CHICKASAW, 1854". Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904. 2:652-653 (accessed December 25, 2006).

- Kappler, Charles (ed.). "TREATY WITH THE CHOCTAW AND CHICKASAW, 1866". Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1904. 2:918-931. (accessed December 27, 2006).

- Luthey, Graydon Dean. “Chickasaw Nation v. United States: The Beginning of the End of the Indian-Law Canons in Statutory Cases and the Start of the Judicial Assault on the Trust Relationship?” American Indian Law Review, vol. 27, no. 2, 2002, p. 553., doi:10.2307/20070704.

- National Geographic Society. “Southeast Native American Groups.” National Geographic Society, 4 Mar. 2020, www.nationalgeographic.org/encyclopedia/southeast-native-american-groups/.

- Wright, Muriel H. "Organization of the Counties in the Choctaw and Chickasaw Nations". Chronicles of Oklahoma 8:3 (September 1930) 315-334. (accessed December 26, 2006).

External links

- Chickasaw Nation, official website

- Chickasaw Nation Video Network - Chickasaw.TV

- Voices of Oklahoma interview with Bill Anoatubby. First person interview conducted on October 18, 2010 with Bill Anoatubby, the tribal Governor of the Chickasaw Nation.