Rajput resistance to Muslim conquests

Before the Muslim conquests in the Indian subcontinent, much of northern and western India was being ruled by Rajput dynasties, who were a collection of martial Hindu families.[2] The Rajput kingdoms contended with various Muslim rulers, including various sultans and the Mughals.

|

|

|

|

|

Delhi Sultanate

Mamluk Dynasty

During Iltutmish's reign the Rajput states of Kalinjar, Bayana, Gwalior, Ranthambore and Jhalore rebelled against the Turkic governors and gained independence. In 1226 Iltutmish led an army to recapture the lost territories. He was successful in capturing Ranthambore, Jalore, Bayana and Gwalior. However he was unable to conquer Gujarat,Malwa and Baghelkhand. An attack on Nagda, (then capital of Mewar) was also made by Iltutmish and was repelled by a combined army of Mewar and Gujarat (under the Chalukya's).[3] After Iltutmish's death the Rajput states once again rebelled and the Bhati Rajputs who were entrenched in Mewat, moved out and conquered the areas around Delhi itself.[4]

Khilji Dynasty

Sultan Ala ud din Khilji (1296–1316) conquered Gujarat (1297) and Malwa (1305), captured the fort of Mandu and handed it over to the Songara Chouhans. They captured the fortresses of Ranthambore (1301), Mewar's capital at Chittorgarh (1303), and Jalor (1311), after long sieges with fierce resistance from their Rajput defenders. Ala ud din Khilji also fought the Bhatti Rajputs of Jaisalmer and occupied the Golden Fort. He managed to capture three Rajput forts of Chitor, Ranthambore and Jaisalmer, but couldn't hold them for long.[5]

Tuglaq Dynasty

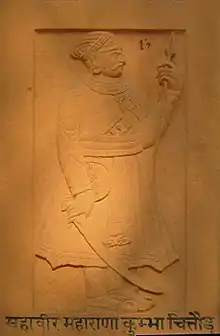

The Mewar reestablished their supremacy within 50 years of the sack of Chittorgarh, under Rana Hammir. In 1336, Hammir defeated Muhammad Tughlaq in the Battle of Singoli[6] with Hindu Charans as his main allies, and captured him. Tughlaq had to pay a huge ransom and relinquish all of Mewar's lands. After this the Delhi Sultanate did not attack Chittorgarh for a few hundred years. The Rajputs reestablished their independence, and Rajput states were established as far east as Bengal and north into the Punjab. The Tomaras established themselves at Gwalior, and the ruler Man Singh Tomar built the fortress which still stands there. Mewar emerged as the leading Rajput state, and Rana Kumbha expanded his kingdom at the expense of the sultanates of Malwa and Gujarat.[7]

Built during the course of the 15th century by Rana Kumbha, the walls of the fort of Kumbhalgarh extend over 38 km, claimed to be the second-longest continuous wall after the Great Wall of China.

Built during the course of the 15th century by Rana Kumbha, the walls of the fort of Kumbhalgarh extend over 38 km, claimed to be the second-longest continuous wall after the Great Wall of China. City Palace was constructed by Maharana Udai Singh II after shifting his capital to Udaipur due to Muslim invasion.

City Palace was constructed by Maharana Udai Singh II after shifting his capital to Udaipur due to Muslim invasion..jpg.webp) Amer Fort and Jaigarh Fort are connected by subterranean passages, and are known for their artistic Hindu Rajput style elements.

Amer Fort and Jaigarh Fort are connected by subterranean passages, and are known for their artistic Hindu Rajput style elements. Entrance eastern façade of the Junagarh Fort. Historical records reveal that despite the repeated attacks by enemies to capture the fort, it was not taken, except for a lone one-day occupation by Mughal prince Kamran Mirza.

Entrance eastern façade of the Junagarh Fort. Historical records reveal that despite the repeated attacks by enemies to capture the fort, it was not taken, except for a lone one-day occupation by Mughal prince Kamran Mirza.

Sayyid Dynasty

The Delhi Sultanate took advantage of Rao Jodha's war with Rana Kumbha and captured several Rathore strongholds including Nagaur, Jalore and Siwana. After a few years Rao Jodha formed an alliance with several Rajput clans including the Deora's and Bhati's and attacked the Delhi army, he succeeded in capturing Merta, Phalodi, Pokran, Bhadrajun, Sojat, Jaitaran, Siwana, Nagaur and Godwar from the Delhi Sultanate. These areas were permanently captured from Delhi and became a part of Marwar.[8]

Lodi Dynasty

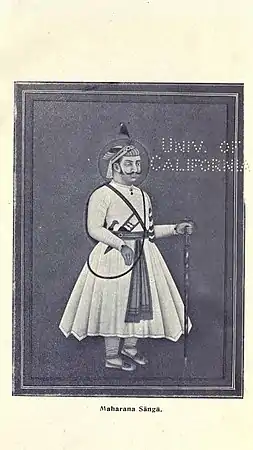

Rajputs under Rana Sanga managed to defend and expand their confederation against Sultanates of Malwa, Gujarat and also Ibrahim Lodi, Sultan of Delhi. Sanga defeated Ibrahim Lodi in two major battles at Khatoli and Dholpur. The Rana annexed Delhi territory up to Pilia Khar, a river on the outskirts Agra.[9][7]

Gujarat Sultanate

The Kumbalgarh inscription says that Rana Kshetra Singh captured Zafar Khan, the Sultan of Patan (First Independent Sultan of Gujarat) in a battle.[10]

Ahmad Shah II, the sultan of Gujarat captured Sirohi and attacked Kumbhalmer in reaction to Rana Kumbha's meddling in the affairs of Nagaur Sultanate. Mahmud Khalji, the Sultan of Malwa and Ahmad Shah II reached an agreement (treaty of Champaner) to attack Mewar and divide the spoils. Ahmad Shah II captured Abu, but was unable to capture Kumbhalmer, and his advance towards Chittor was also blocked. Rana Kumbha allowed the army to approach Nagaur, when he came out, and after a severe engagement, inflicted a crushing defeat on the Gujarat army, annihilating it. Only remnants of it reached Ahmedabad, to carry the news of the disaster to the Sultan.[11]

In a series of battles of Idar from 1514 to 1517 forces of Rana Sanga of Mewar defeated forces of Sultan of Gujarat. In 1520 Rana Sanga led a coalition of Rajput forces to invade Gujarat. He defeated the Sultan's army under command of Nizam Khan and plundered the wealth of Gujarat Sultanate. Muzaffar Shah II, the Sultan of Gujarat fled to Champaner.[12]

Rana also defeated the joint forces of Gujarat and Malwa Sultanates in the Siege of Mandsaur and the Battle of Gagron.[13] In 1526 A.D. the Rana gave protection to the fleeing Gujarat princes, the Sultan of Gujarat demanded their return and after the refusal from the Rana, sent his general Sharza Khan Malik Latif to bring the Rana to terms. In the battle that followed Latif and 1700 of the Sultans soldiers were killed, the rest were forced to retreat to Gujarat.

Malwa Sultanate

Rana Kshetra Singh increased his fame by defeating the Sultan of Malwa and killing his general Ami Shah.[14]

Sultan Mahmud Khilji sent his army with Sultan of Gujarat against Maharana Kumbha which was defeated by Kumbha at the Battle of Nagaur in 1455[15]

Sangram Singh defeated the joint forces of Gujarat and Malwa Sultanates in the Siege of Mandsaur and the Battle of Gagron. The Sultan of Malwa was captured and was kept as a prisoner in Chittorgarh for 6 months. He was released after his assurance of future good behaviour, Rana as surety kept his son as hostage.[16]

Nagaur Sultanate

The ruler of Nagaur, Firuz (Firoz) Khan died around 1453-1454. Shams Khan (the son of Firuz Khan) initially sought the help of Rana Kumbha against his uncle Mujahid Khan, who had occupied the throne. After Shams Khan became Sultan of Nagaur with the help of Rana Kumbha, he refused to weaken his defenses as promised to Rana, and sought the help of Ahmad Shah II, the Sultan of Gujarat (Ahmad Shah died in 1442). Angered by this, Kumbha captured Nagaur in 1456, and also Kasili, Khandela and Sakambhari.

In reaction to this, Ahmad Shah II captured Sirohi and attacked Kumbhalmer. Mahmud Khalji of Malwa and Ahmad Shah II reached an agreement (treaty of Champaner) to attack Mewar and divide the spoils. Ahmad Shah II captured Abu, but was unable to capture Kumbhalmer, and his advance towards Chittor was also blocked. Rana Kumbha allowed the army to approach Nagaur, when he came out, and after a severe engagement, inflicted a crushing defeat on the Gujarat army, annihilating it in the Battle of Nagaur. Only remnants of it reached Ahmedabad, to carry the news of the disaster to the Sultan.[17]

Rana Kumbha took away from the treasury of Shams Khan a large store of precious stones, jewels and other valuable things. He also carried away the gates of the fort and an image of Hanuman from Nagaur, which he placed at the principal gate of the fortress of Kumbhalgarh, calling it the Hanuman Pol. Nagaur Sultanate ceased to exist after this disaster.[18]

Jaunpur Sultanate

In the eastern regions of the subcontinent, the Ujjainiya Rajputs of Bhojpur came into conflict with the Jaunpur Sultanate. After a prolonged struggle, the Ujjainiyas were driven into the forest where they continued to carry out a guerrilla resistance.[19]

Mughal Empire

Taking advantage of the instability in Punjab, the ambitious Timurid prince, Babur invaded Hindustan and defeated Ibrahim Lodi at the First Battle of Panipat on 21 April 1526.[20] Rana Sanga rallied a Rajput army to challenge Babur. Babur defeated the Rajputs at the Battle of Khanwa on 16 March 1527, with his superior techniques and military capabilities.[7]

Rajputs at the rise of the Mughals

Soon after his defeat in 1527 at the Battle of Khanwa, Rana Sanga died in 1528. Bahadur Shah of Gujarat became a powerful Sultan. He captured Raisen in 1532 and defeated Mewar in 1533. He helped Tatar Khan to capture Bayana, which was under Mughal occupation. Humayun sent Hindal and Askari to fight Tatar Khan. At the battle of Mandrail in 1534, Tatar Khan was defeated and killed. Puranmal, the Raja of Amber, helped the Mughals in this battle. He was killed in this battle. Meanwhile, Bahadur Shah started his campaign against Mewar and led his army against the fort of Chittorgarh, the defense of the fort was led by, Rani Karnavati, widow of Rana Sanga, she started preparing for a siege and smuggled her young children to the safety of Bundi. Mewar was weakened due to constant struggles. After the Siege of Chittorgarh (1535), Rani Karnavati, together with other women, committed Jauhar. The fort was soon re-captured by the Sisodia's. The Mughal emperor Akbar, tried to persuade Mewar to accept Mughal sovereignty, like other Rajputs, but Rana Udai Singh refused. Ultimately Akbar besieged the fort of Chittor leading to the Siege of Chittorgarh (1567–1568). This time, Rana Udai Singh was persuaded by his nobles to leave the fort with his family. Jaimal Rathore of Merta and Fatah Singh of Kelwa were left to take care of the fort. On 23 February 1568, Akbar shot Jaimal Rathore with his musket, when he was looking after the repair work. That same night, the Rajput women committed jauhar (ritual suicide) and the Rajput men, led by the wounded Jaimal and Fateh Singh, fought their last battle. Akbar entered the fort, and at least 30,000 civilians were killed. Later Akbar placed a statue of these two Rajput warriors on the gates of Agra Fort.[7]

Akbar and Rajputs

Akbar won the fort of Chittorgarh, but Rana Udai Singh was ruling Mewar from other places. On 3 March 1572 Udai Singh died, and his son, Maharana Pratap, sat on the throne at Gogunda. He vowed that he would liberate Mewar from the Mughals; until then he would not sleep on a bed, would not live in a palace, and would not have food on a plate (thali). Akbar tried to arrange a treaty with Maharana Pratap, but did not succeed. Finally, he sent an army under Raja Man Singh in 1576. Maharana Pratap was defeated at the Battle of Haldighati in June 1576. However he escaped from the battle and started guerrilla warfare with the Mughals . After years of struggling, Maharana Pratap was able to defeat the Mughals at the battle of Dewair( not to be confused with the battle of Dewar where his son Rana Amar Singh fought). The Bargujars were the main allies of the Ranas of Mewar. Maharana Pratap died on 19 January 1597, and Rana Amar Singh succeeded him. Akbar sent Salim to attack Mewar in October 1603, but he stopped at Fatehpur Sikri and sought permission from the emperor to go to Allahabad, and went there. In 1605 Salim sat on the throne and took the name of Jahangir.[7]

Chandrasen Rathore defended his kingdom for nearly two decades against relentless attacks from the Mughal Empire. Mughals were not able to establish their direct rule in Marwar until Chandrasen was alive.[21]

Jahangir and Rajputs

Jahangir sent an army under his son Parviz to attack Mewar in 1606 which was defeated in the Battle of Dewar. The Mughal emperor sent Mahabat Khan in 1608. He was recalled in 1609, and Abdulla Khan was sent. Then Raja Basu was sent, and Mirza Ajij Koka was sent. No conclusive victory could be achieved. The disunity among various clans of Rajwada didn't allow Mewar to be completely liberated. Ultimately Jahangir himself arrived at Ajmer in 1613, and appointed Shazada Khurram to fight against Mewar. Khurram devastated the areas of Mewar and cut the supplies to the Rana. With the advice of his nobles and the crown prince, Karna, the Rana sent a peace delegation to Prince Khurram, Jahangir's son. Khurram sought approval of the treaty from his father at Ajmer. Jahangir issued an order authorising Khurram to agree to the treaty. The treaty was agreed between Rana Amar Singh and Prince Khurram in 1615.

- The Rana of Mewar accepted Mughal suzereignty.

- Mewar and the fort of Chittorgarh was returned to Rana.

- The fort of Chittorgarh could not be repaired or renovated by Rana.

- The Rana of Mewar would not attend the Mughal court personally. The crown prince of Mewar would attend the court and give himself and his army to the Mughals.

- There would be no matrimonial alliance of Mewar with the Mughals.

This treaty, considered respectable for both parties, ended the 88-year-long enmity between Mewar and the Mughals.[7]

Aurangzeb and Rajput rebellion

The Mughal emperor Aurangzeb (1658–1707), who was far less tolerant of Hinduism than his predecessors, placed a Muslim on the throne of Marwar when the childless Maharaja Jaswant Singh died. This enraged the Rathores, and when Ajit Singh, Jaswant Singh's son, was born after his death, the Marwar nobles asked Aurangzeb to place Ajit on the throne. Aurangzeb refused, and tried to have Ajit assassinated. Durgadas Rathore and the dhaa maa (wet nurse) of Ajit, Goora Dhaa (the Sainik Kshatriya Gehlot Rajputs of Mandore), and others smuggled Ajit out of Delhi to Jaipur, thus starting the thirty-year Rajput rebellion against Aurangzeb. This rebellion united the Rajput clans, and a triple-pronged alliance was formed by the states of Marwar, Mewar, and Jaipur. One of the conditions of this alliance was that the rulers of Jodhpur and Jaipur should regain the privilege of marriage with the ruling Sisodia dynasty of Mewar, on the understanding that the offspring of Sisodia princesses should succeed to the throne over any other offspring. Chhatrasal waged war against the Mughals and after leading a successful rebellion established his own kingdom which extended over most of the Bundelkhand.[1]:187–188

References

- Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. ISBN 978-9-38060-734-4.

- Sandler, Stanley (2002). Ground Warfare: An International Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 717. ISBN 978-1-57607-344-5.

Drawing their name from Rajasthan—the northwestern region of modern India, roughly between Delhi and Pakistan—the Rajputs were a collection of Hindu families whose military and political power dated from preconquest times. Under Mogul rule, Rajasthan remained a tangle of opposition combining the prickliest of resistance with the least rewards.

- History of Medieval India by Satish Chandra pg.86

- History of Medieval India by Satish Chandra pg.97

- "Rajput". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- R. C. Majumdar, ed. (1960). The History and Culture of the Indian People: The Delhi Sultante (2nd ed.). Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. p. 70.

- John Merci, Kim Smith; James Leuck (1922). "Muslim conquest and the Rajputs". The Medieval History of India pg 67-115

- Kothiyal, Tanuja (2016). Nomadic Narratives: A History of Mobility and Identity in the Great Indian. Cambridgr University Press. p. 76. ISBN 9781107080317. Retrieved 17 September 2020.

- Chandra, Satish (2006). Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals (1206–1526) 2. Har-Anand Publications.

- Sastri, Hirananda (1931). Epigraphia Indica Vol.21. pp. 277–288.

- Sarda, Harbilas (March 2007). Maharana Kumbha: Sovereign, Soldier, Scholar. Read Books. p. 56. ISBN 978-1-4067-3264-1.

- Firishtah, Muḥammad Qāsim Hindū Shāh Astarābādī; Briggs, John (1997). History of the Rise of the Mahomedan Power in India: Till the Year A.D. 1612 Vol 4. Low Price Publications. pp. 81–83. ISBN 978-81-7536-077-8.

- Firishtah, Muḥammad Qāsim Hindū Shāh Astarābādī; Briggs, John (1997). History of the Rise of the Mahomedan Power in India: Till the Year A.D. 1612, Vol 4. Low Price Publications. pp. 262–63. ISBN 978-81-7536-077-8.

- Sarda, Har Bilas (1917). Maharana Kumbha: Sovereign, Soldier, Scholar. Scottish Mission Industries Company. p. 4.

- Sarda, Harbilas (March 2007). Maharana Kumbha: Sovereign, Soldier, Scholar. Read Books. p. 55. ISBN 978-1-4067-3264-1.

- Firishtah, Muḥammad Qāsim Hindū Shāh Astarābādī; Briggs, John (1997). History of the Rise of the Mahomedan Power in India: Till the Year A.D. 1612, Vol. 4. Low Price Publications. pp. 262–63. ISBN 978-81-7536-077-8.

- Sarda, Har Bilas (1917). Maharana Kumbha: Sovereign, Soldier, Scholar. Scottish Mission Industries Company. p. 56.

- Sarda, Har Bilas (1917). Maharana Kumbha: Sovereign, Soldier, Scholar. Scottish Mission Industries Company. p. 55.

- Dirk H. A. Kolff (8 August 2002). Naukar, Rajput, and Sepoy: The Ethnohistory of the Military Labour Market of Hindustan, 1450-1850. Cambridge University Press. pp. 60–62. ISBN 978-0-521-52305-9.

- Chandra, Satish. History of Medieval India. Orient Black Swan. p. 204. ISBN 978-93-5287-457-6.

- Bose, Melia Belli (2015). Royal Umbrellas of Stone: Memory, Politics, and Public Identity in Rajput Funerary Art. BRILL. p. 150. ISBN 978-9-00430-056-9.